Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

I have known Pte Hindle’s name, along with that of Pte William Daniel McCann, for decades. They were the first two Argylls killed in action, and the legendary CSM George Mitchell of C Company took note of their names and the impact of their deaths upon C Coy in his private diary. I am grateful for the help of Doug Hunter of the Argyll Senate and a resident of Niagara-on-the Lake for his help. Dolores Hindle-Derbyshire, a relation, has gone to great lengths in helping with my quest to find an image of Percy Hindle. We have gone down several blind alleys and the pursuit continues. Kevin Sherlock, a distant relative, generously shared his own research. I thank them all. Percy’s older brother, Frank J. Hindle (1920–47), also served with the 1st Battalion. Pte Percy Hindle was wounded at the end of August 1944; the war, it seems, weighed heavily upon him. Pte Hindle’s death, unexpected as it was, was the first “black yesterday” of battle for the Argylls. It would not be the last.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

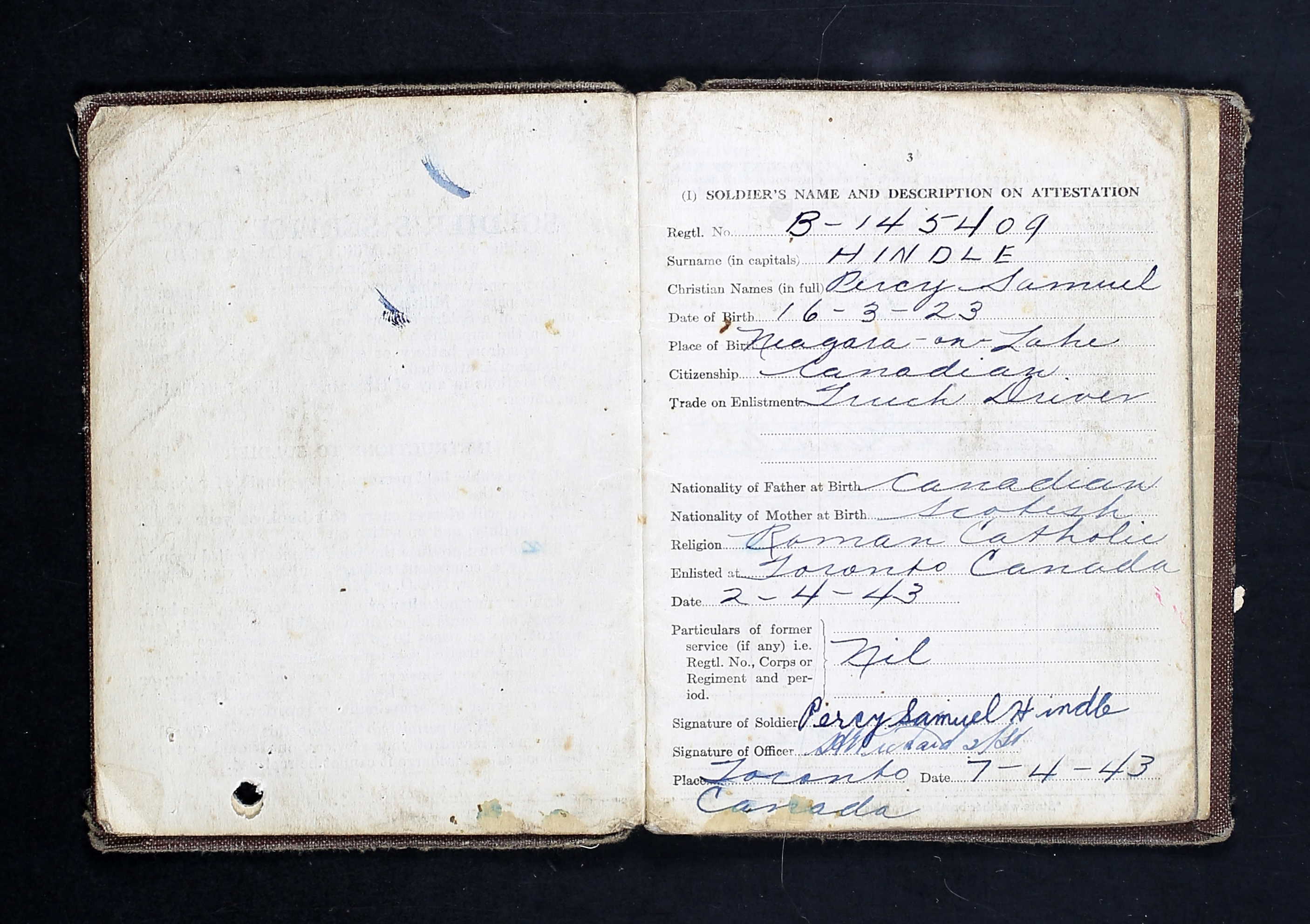

Pte Percy Samuel Hindle (1923–44) (B 145409)

DW 29 July 1944

Percy Samuel Hindle was born on 16 March 1923 in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, the third child of Frank Hindle (1882–1949) and Margaret McWhirter (1888– ). When they married on 8 April 1917, Frank was a carpenter and Margaret (a Scot who had immigrated to Canada in 1913) was a dressmaker. He had enlisted in the 176th Overseas Battalion in St Catharines on 12 May 1916. The unit trained at a campsite in Niagara Falls until it went overseas. Frank was AWOL on four occasions prior to embarking at Halifax for England on 28 April 1917. On a form about family, dated 20 March 1917, a note reads that “Miss Margaret McWhirter” was his fiancée and they were “To be married” this week. Pte Hindle was AWOL at the time of his marriage. He saw action with the 52nd Battalion in 1918, received 14 days for “improper language to an N.C.O.” – shortly after receiving his badge for good conduct. He returned to Canada and was discharged in Hamilton on 29 March 1919. After marrying Percy, Margaret Hindle resided at 819 King Street East in Hamilton, then at 86 Mountain Park Avenue on the “Mountain Top” in Hamilton. By April 1919, she had returned to Niagara-on-the-Lake with her husband. Their first child, Frank J. Hindle (1920–67), was born there, followed by a daughter the next year, and Percy in 1923. The couple had three more children afterwards.

“to go to work to assist his family”

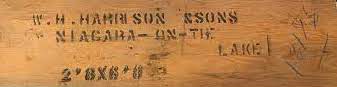

The Hindles lived on Gate Street (the number is unspecified). Percy attended school, completing grade 6 before leaving at age 15 “to go to work to assist his family.” He did “odd jobs” as an electrician’s helper, plumber’s helper, carpenter’s helper, and truck driver for 4½ years. In the seven months before enlisting, he worked as a truck driver for six months at W.H. Harrisons & Sons (a lumber company) and one month at Muir’s Drydock punching steel plate. As for his weekly wage, the army interviewer noted “Various.” His hobby was “trapping” and he enjoyed skating, swimming, and hunting. He played hockey and softball.

“Called + volunteered active at once”

Percy’s older brother, Frank, had enlisted with the Argylls in 1940 after the unit was mobilized. Percy enlisted on 1 April 1943. On 18 January 1944, an army interviewer recorded Hindle’s reason for joining the army: “Called + volunteered active at once.” The 1943 army examiner wrote of Hindle’s personal history and offered this appraisal:

This young recruit of limited army ability is of a friendly, co-operative manner with clean appearance, tall strong build (weight 157 lbs., height 5’ 11 3/4”), normal habits and stability. He states his health is OK now but has been troubled with rheumatism in both knees, and last year he had sinus trouble. He is interested in hockey, baseball, hunting, trapping and swimming and enjoys reading western stories. He states he has an older brother in the Argyle [sic] and Sutherland Highlanders. This man enjoys his home life and has not been away from home for any lengthy periods but nevertheless he feels he will be quite happy in and enjoy army life. He expressed a desire for driving in the army having had about a year’s truck driving experience. He should be capable of complete Infantry training and if his progress is favourable might be used as a driver.

The examiner recommended Hindle for “INFANTRY (R) NON TRADESMAN.”

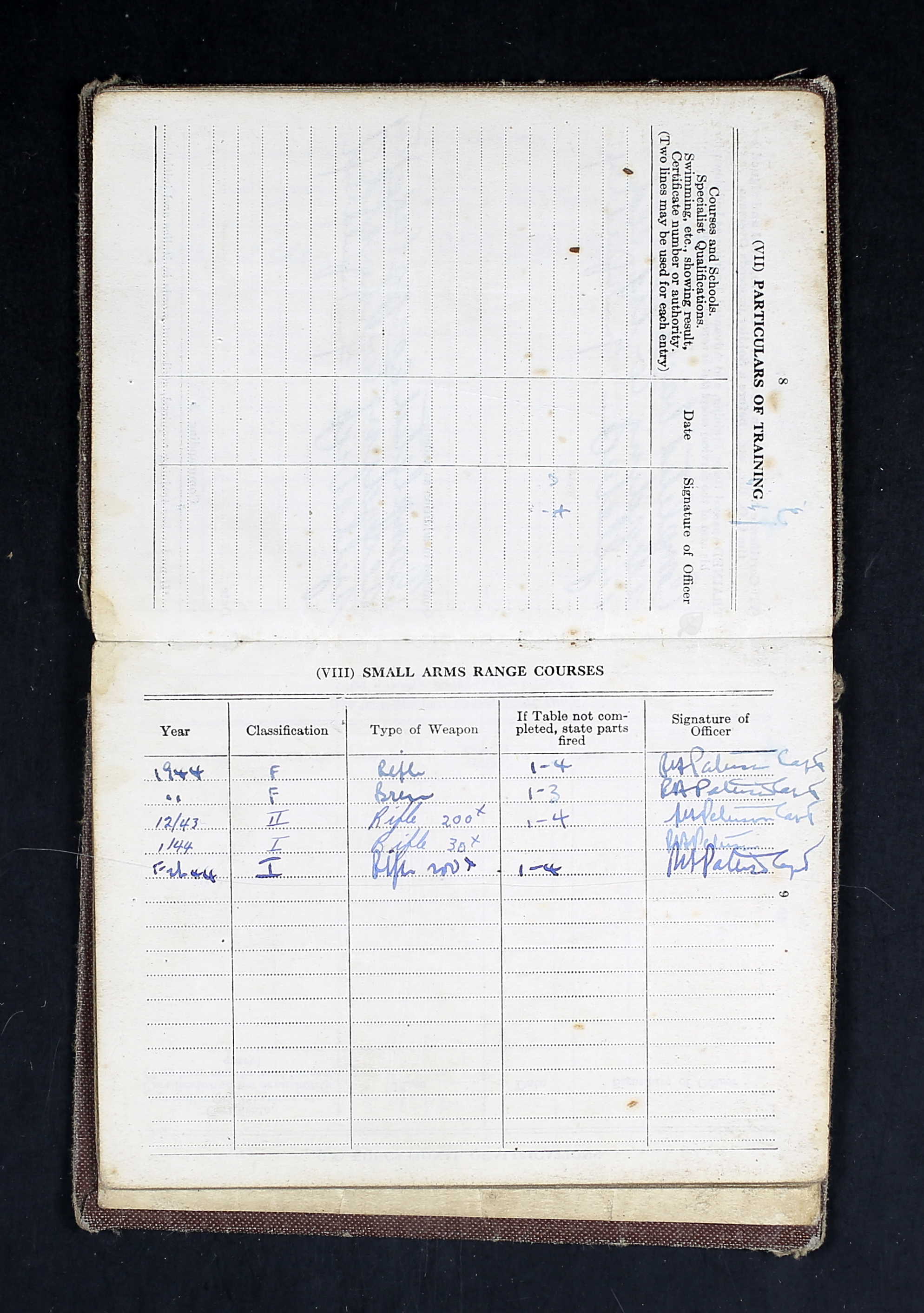

Record of Small Arms Range Courses completed by Pte Percy Samuel Hindle. Signed by Capt R.A. Paterson, C Company.

“INFANTRY (R) NON TRADESMAN”

Pte Hindle transferred from #2 District Depot in Toronto to #20 BTC BFD [Basic Training Centre, Brantford]. On 15 June 1943 he was taken on strength by the Argylls at Niagara-on-the-Lake; he had joined his brother’s battalion, which had returned from 22 months in Jamaica in late May 1943. The battalion marched into Niagara Camp on 26 May 1943. In June “eight other ranks were taken on strength” (including Pte Hindle) and 129 were struck off strength by reason of age or medical condition. On 5 July, 152 other ranks joined the battalion from Camp Shilo, Manitoba. The battalion entrained for Sussex, New Brunswick, on 9 July, boarded the Queen Elizabeth on 21 July, and arrived in Gourick, Scotland, on the 27th. The following day the Argylls were on trains again crossing the border to England during the night of the 28th. The train “arrived at Camberley at 1215 hours. The troops detrained and marched to separate billets – large unoccupied homes.” There were battalion parades, church parades, route marches, passes, medical inspections, leaves, new equipment, and a new training syllabus of refresher courses in every aspect of infantry life. The “emphasis” was, as Lt Don Seldon of the Mortar Platoon put it, “on physical condition and basic training” because the “fate of the battalion – whether it is to be dissolved and the personnel used as reinforcements, or absorbed as a unit into a division – still hangs in the balance.” Maj Art Hay, the acting CO, was a “hard taskmaster” and a “disciplinarian.” Happily, the unit passed muster on 17 August. By early September the battalion was at New Hunstanton, which was “cold and uncomfortable.” On the 18th, Hindle forfeited four days’ pay “for one off. Under AA 11 [failure to obey an order].” The incident occurred in the “Field.” At the end of the month, the Argylls were in the field on a “great long exercise” as one platoon commander expressed it.

“the training here is plenty tough”

On 1 October, with the new CO, Lt-Col J. David Stewart, who “marched with the men,” the battalion moved to Riddlesworth Camp. “A regimental piper preceded each company as an aid to flagging feet, but blisters and blasphemy were common.” There were more reinforcements on the first day at, as Pte John Booth expressed it, “the dirtiest camp we ever moved into and it took plenty of work to make it fit to live in.” Hindle was in C Company, one of the four rifle companies. Pte Jamie MacRae was one of the new reinforcements and posted to C. He wrote to his parents that “the spirit of cooperation and friendliness is much more apparent than in any camp I have been in yet which is a pleasant change. On 10 October he wrote that he had “been pretty busy the past week and the training here is plenty tough. We are in the field two days and in the camp one … The fellows here are all nice to be with. They have been together long enough that petty jealousies are not apparent and all are more helpful to the new men.” Seven days later he commented that “Our training is interesting, tough and thorough … discipline is rigid.” On the 19th the battalion was on a major exercise “Grizzly II – Battle manoeuvre in conjunction with tanks is the order of the day with all rifle companies engaged.” The “weather was terrible” and the troops were “wet and miserable.” Capt Bob Paterson, the 2ic of C Company, described it as “awful, absolutely awful … it was all mess up. We had no fires, nothing … and everything went wrong.”

“the normal military groove”

After another large exercise at the start of November, the Argylls moved – “Reveille at 0430 hours” – on 6 November to new quarters in Uckfield, Sussex. The various companies were “quartered in large manor houses … The Cedars (‘C’), – all within 5 miles of Uckfield.” The companies concentrated “chiefly on conditioning work – including speed marches” as “life” settled “down into the normal military groove.” “Complaints,” observed Lt Milt Boyd, the unit war diarist, “are chiefly concerned with English heating and plumbing equipment, which falls somewhat short of Canadian standards.” There were leaves, the Pipe Band played “Retreat” for the first time since the Argylls’ arrival in the United Kingdom. C Company held a dance, “long postponed due to operations in the field,” on the 12th. “Femininity was present in quality and quantity, beer inexpensive and reasonably plentiful, the food appetizing and in abundance.” The Lincoln and Welland band “provided music of the highest calibre” and there was a “jitterbug context.” On the 18th, Private Hindle’s daily rate of pay was increased from $1.40 to the Regimental rate of $1.50. There were more new faces, plenty of time on the rifle ranges, more field exercises, new weapons, and Christmas celebrations with parties for local children, Christmas food, and, as reported by Pte MacRae, “every man in our coy had at least one parcel from home and some got several.”

Soldier’s Service Book – Pte Percy Hindle.

“Strong looking boy of mediocre ability”

An officer interviewed Hindle on 18 January 1945. He found Hindle’s deportment and grooming satisfactory, his disposition “Sociable,” and his physical appearance “Robust.” Overall, he was a “Strong looking boy of mediocre ability; normally sociable + co-operative” but with “little will power.” There was no surprise in the officer’s recommendation for his employment: “Inf (R) as at present.” In February 1945, the unit moved to Inverary, Scotland, for amphibious training and then further training and exercises back in Uckfield along with inspections by an array of important figures, including King George VI. On 2 April 1944, the “RF personnel [Hindle was Roman Catholic] had a special church parade … The usual practice is for them to attend church individually.” In May, the “general trend of trg [training] consists now of hardening exercises, route marches, short five mile speed marches. Whenever possible, coys and sqns [squadrons] of tks [tanks] combine their trg in ‘Infantry cum Tanks’ tactics.”

“We are a good way from the front so don’t worry”

On 6 June 1944, Lt Boyd wrote in the war diary, “This is D Day for the invasion of France.” Three days later, the unit held a muster parade to read an extract from a routine order: “All rks … are warned for embarkation for special duty overseas.” Pte MacRae wrote his parents on the 11th: “We are well trained and our equipment is perfect so we are ready for the orders to move and most of the boys are anxious to be moving.” Lt Alf Henderson of C Company wrote home on the 18th: “The boys are tired waiting around and really anxious to get going.” By mid-July, “information was received … of the adv [advance] party for overseas duty.” On the 19th – the day the battalion began its movements to Tilbury docks – CSM George Mitchell of C Company wrote in his diary: “Fitting that the following notations should be done in Red. Embark for France. Excitement.” Two days later, Pte Hindle (with the main body) disembarked in France. Mitchell, with No. 2 Party, arrived on the 26th. “France!!” he noted in his diary,” – Great anticipation.” Lt Gord Sloane, C Company, concluded a letter to his sister on the following day with the reassurance: “We are a good way from the front so don’t worry [it would be his last letter home] …”

“The fortunes of war, somebody got it”

After four years of training for battle, the early scenes of war’s destruction in Normandy had a wrenching effect. On the 28th, Argylls saw Caen. CSM Mitchell wrote: “Caen smashed – leaves one with hopeless feeling.” Sgt Ed Dickinson of the Mortar Platoon remembered it well: “This side of Caen we were bombed, and the Germans were lobbing over 88s [shells from 88mm guns], and they got some of our guys … we’d just gotten there and dug in. The fortunes of war, somebody got it.”

Lt-Col Stewart had anticipated as much. He later reminisced:

… When we got there, General Montgomery called in the Lieut. Colonels and told us that he had to go back on his promise, to “ease us into battle” and we would go in that afternoon and in we went. We were embussed and I told the drivers of the buses that our speed was “all out.” I warned the men that they had to get off the bus in a hurry and rush to the slit trenches and get down. It was in the heat of summer and the buses made a lot of dust and this attracted the Germans and they started shelling, but not before we were in the slits and the British Regiment, that we relieved, were in the buses. We were safe and the Brits got hell from the shelling.

“First casualties – P. Hindle – McCann. Coy despondent – realize that it’s war”

Safety in battle is a relative term and, for the most part, Argylls were safe except for one Argyll killed in action, one who died from his wounds that day, and one wounded. The two deaths were C Company’s and the effect was immediate. Mitchell noted, “First casualties – P. Hindle – McCann. Coy despondent – realize that it’s war. Enemy shelling hot and heavy.”

Pte Dick Gillespie, a piper, was a stretcher-bearer [see Richard McDonald] attached to ‘C’ Coy.” “I don’t think any of us had any idea of what to expect when first going into action. Our first day and night in the battle zone, we were subjected to some light shelling and at dusk some sniper fire from a close by ridge … our Coy. had 2 killed the first day, Pte.’s Hindle and McCann.” Cpl Buck Edwards recalled the loss vividly:

I lost the first two [Hindle and McCann] … because of air bursts … in that instance, everybody ran over to see if they could help, which was a very poor thing to do. Lesson number one: let the Sergeant go down. If he needs help, help him. But if there’s no chance of survival, call the stretcher bearers. But the first one was rough and it was a good lesson. We got them dispersed and back in their holes and told them to cover up …

“And we went over to look at him, and then it dawned on us that this was it, this was the real thing”

Pte John “Pinky” Craig remembered it too:

… a fellow from Niagara-on-the-Lake, Percy Hindle, he got killed. He was, of all things, laying out and sunning himself on the side of his slit trench, and a shell landed and killed him … And we went over to look at him, and then it dawned on us that this was it, this was the real thing. And from that day on, there was that little bit of fear at the back of your mind all the time.

Well, it wasn’t a little bit of fear, it was a lot of times a tremendous amount of fear. Your mouth was dry and you couldn’t eat; your stomach couldn’t accept food; and it got to be pretty grim after a while … I was afraid many a time … How can you not be afraid?

Pte Hindle was wounded and died of his wounds the same day; Pte William Daniel McCann, a 26-year-old farm hand from Oshawa with a wife and two young children and a grade 5 education, was killed instantly; Pte Wilfred (Bill) M. Raymond (1924–2005) was wounded.

Ptes Hindle and McCann, sharing the same slit trench, died in a relatively peaceful area during the Argylls’ first day in the “battle zone.” As the (soon to be proven) fearsome CSM of C Company admitted “[we] realize it’s war.” That awareness was accompanied by the curiosity of the battalion’s first deaths in battle. As Pte Craig admitted, “we went over to look at him.” He reached an immediate conclusion: “it dawned on us that this was it, this was the real thing.” Death in battle had a handmaiden. “And from that day on,” Craig confessed, “there was that little bit of fear at the back of your mind all the time.”

Your title here…“The dead then joined a shadowy company that grew in numbers each day”

“In battle,” Capt Claude Bissell opined, “death became a statistic, noted with sad resignation. The dead then joined a shadowy company that grew in numbers each day.” Pte Percy Samuel Hindle was one of the Argylls’ two first statistics. HCapt Charlie Maclean, the beloved unit padre, oversaw their passage to the “shadowy company” of the dead. He buried them in temporary graves within a “walled garden” “next to Caves Fleury-Sur-Orne.” The service was brief and reverent, and a Regimental piper played the Argylls’ lament, “Flowers of the Forest.” In the months after the war, Maj Hugh Maclean wrote his draft history of the 1st Battalion. He took note of the first casualties and their impact on the unit. “Many men realized for the first time,” he wrote, “that they were really in a war.”

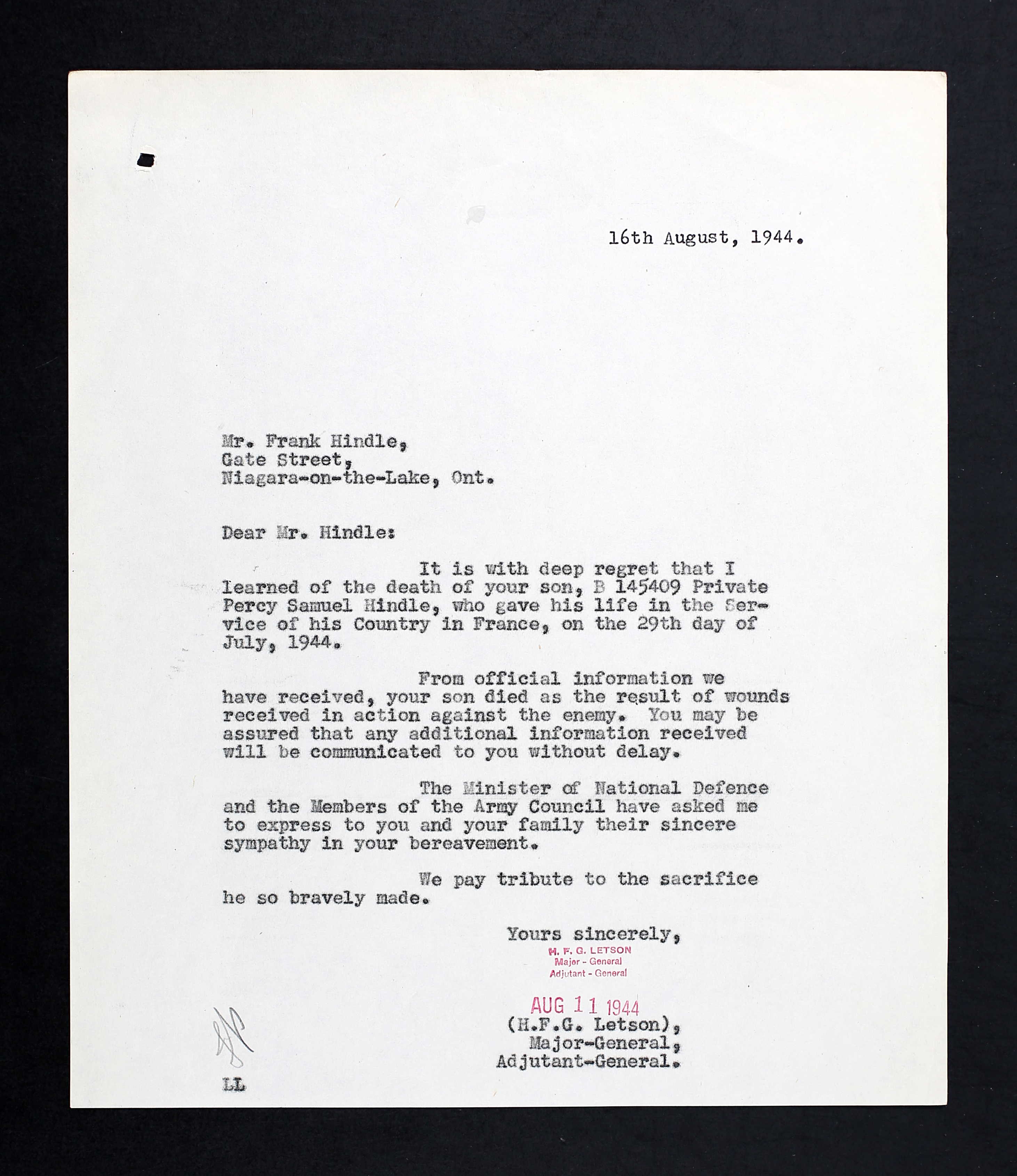

Adjutant-General to Frank Hindle, 16 August 1944.

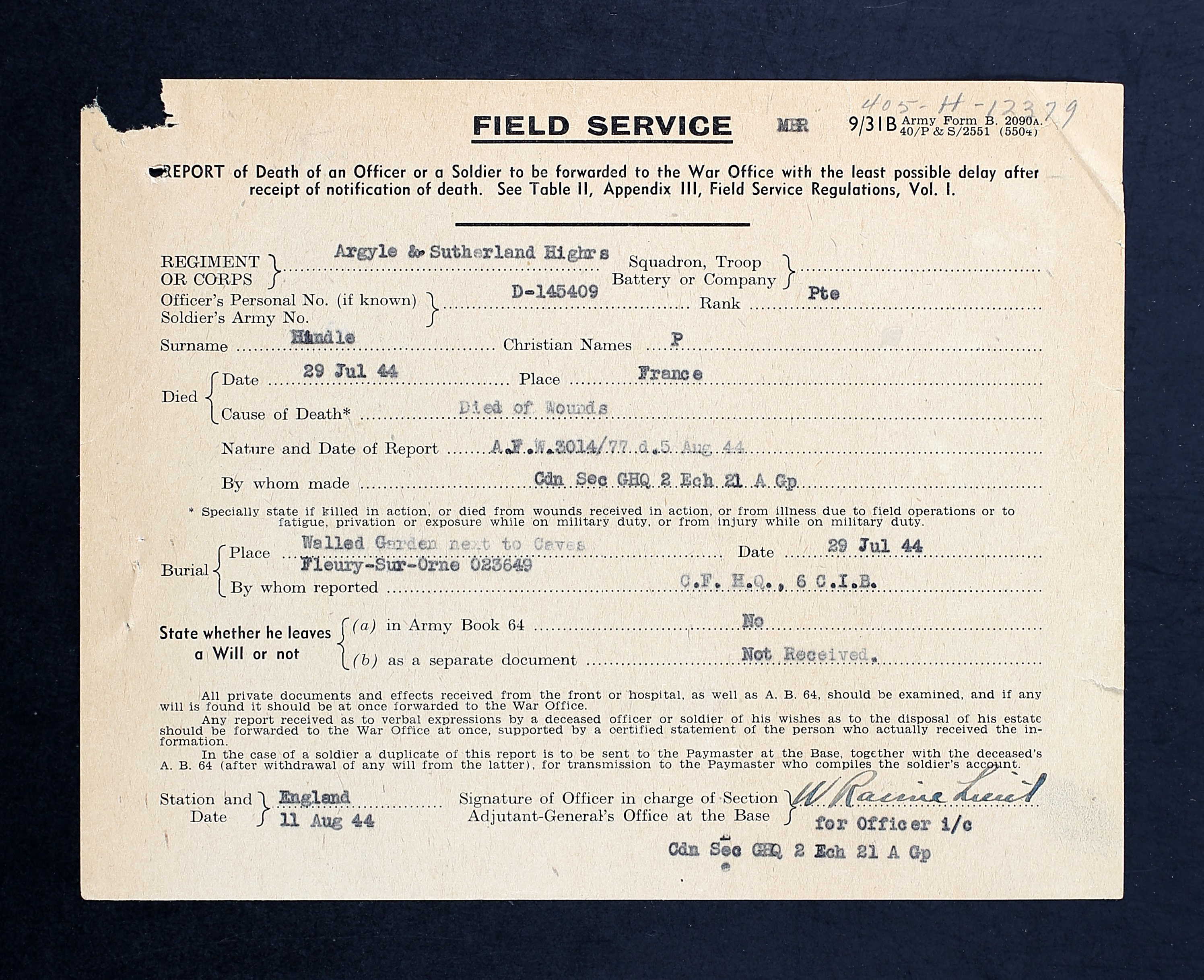

Field Service Form – Pte Hindle, 11 August 1944.

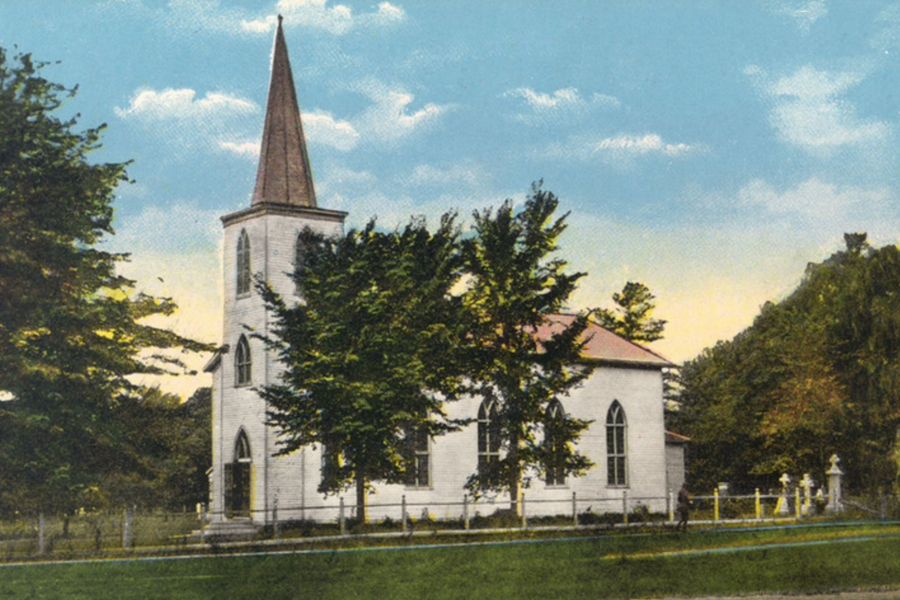

“The service was largely attended”

The army notified Hindle’s parents of his death. A requiem high mass was performed in his memory at St Vincent de Paul Roman Catholic Church in Niagara-on-the-Lake on Monday, 14 August 1944. “The service was largely attended, members of the Canadian Legion and the Ladies Auxiliary parading to the church.” He left his meagre estate to his father along with a mere handful of personal effects: an identification disc, a receipt for a $50 Victory Loan, an identification card, a leather billfold, and “snapshots.” In the post-war period, Joseph E. Masters, a former town clerk and local historian, remembered “Percy, one of Frank’s boys, lost his life ‘over there’ and a very nice boy he was.” Pte Hindle was reburied in his final resting place at Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery. Next of kin could choose an inscription; his parents commemorated him with a brief verse:

IN LOVING MEMORY OF PERCY

SWEETLY TENDER

FOND AND TRUE

EVERY DAY WE THINK OF YOU

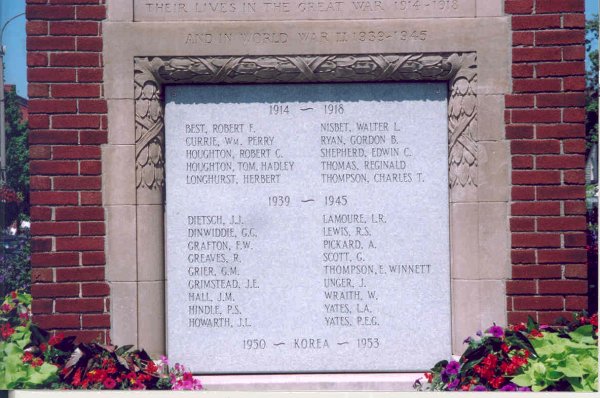

Pte Hindle’s name is inscribed on the cenotaph at Niagara-on-the-Lake. His younger brother, David, was killed by a friend in 1952. His older brother, Frank, died in 1967 and is buried at St Vincent de Paul Cemetery. He was wounded on 29 August 1944 at Boos when “two mortar bombs landed in the vicinity of BHQ.” His grave marker suggests the primacy of wartime experience of a Hindle:

FRANK J. HINDLE

PRIVATE

A. & S. H. OF CDA (P.L.)

31 DEC. 1967

AGE 47

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Note: Pte Hindle’s poppy is included in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the middle cluster near the centre. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy for the Field of Remembrance.

Sign from W.H. Harrison & Sons, Niagara-on-the-Lake.

View of Muir’s Drydock today.

Gravestone at Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery.

Cenotaph, Niagara-on-the-Lake.

St Vincent de Paul Roman Catholic Church, Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Gravestone of Pte Frank J Hindle, St Vincent de Paul Cemetery, Niagara-on-the-Lake.