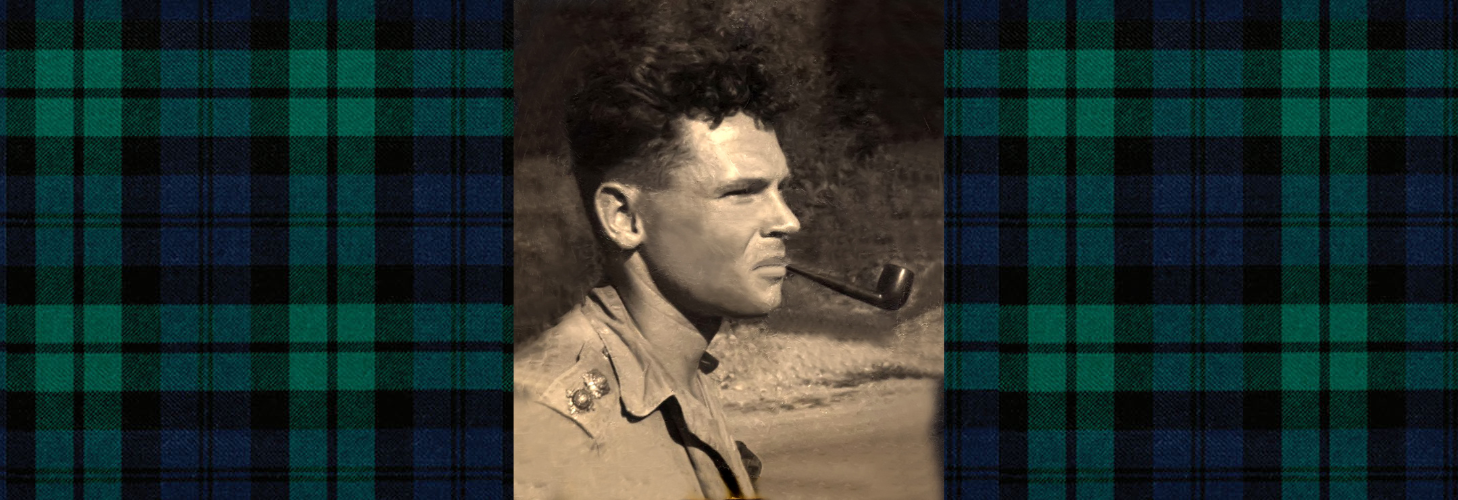

Bob Paterson was born in Hamilton in 1916 and grew up on Homewood Avenue

in the city’s west end. He graduated from McMaster University in 1938 and then went

to work in Toronto for London Life. He was, as he put it, vaguely away

of events in Europe but “life pretty well went on.” A sportsman all of

his life (he acquired the nickname “Flan” for his devotion to flannel

socks), he was in Algonquin Park in May 1940, fishing with his dad, when

the German army broke through the famed Maginot Line. “Then I knew that

the game was up…. I knew it was an all or nothing situation. You just

damn well had to join.”

Paterson had begun officers’ training in September 1939 when the war

broke out. He had his qualifications as a gunner and tried,

unsuccessfully, to join the Guelph and then the Hamilton battery in May

1940. His brother-in-law, 2Lt Dave Duncan, was in the Argylls and

“telephoned one night in June and said, ‘The Argylls are being

mobilized, seven or eight of your friends from McMaster and myself have

all joined up. Why don’t you come down and take a crack at it?’ And

that’s how I got into the Argylls.”

The introduction to military proved as interesting for Paterson as it

did for most others: “My commission was dated June and I was taken on

… provisional second lieutenant, supernumerary … I was the lowest of

the low.” He admitted to being “pretty green…. We had no military

training at all. We didn’t know how to dress properly, how to salute,

how to march, how to do a damn thing, and [we] were given men to

command. It was pretty awful.”

In time, Paterson, like the men of the Battalion as a whole, became soldiers. His

brief artillery training made him a natural fit for command of the

mortar platoon, although it did not have any mortars for some time. Years

later, 2Lt Pete Stephen could still “see him out on the training area,

trying to teach them how to fire a mortar with a piece of stovepipe and

sticks of wood that fitted in the stovepipe.” But leadership does not

depend on equipment, and Paterson was making an impact on his men without

it. Pte Mike Forester, a tough young lad from Grimsby, thought, “Oh gosh,

Paterson was a prince. I really liked [him]…. He was a very

quiet-spoken man…. He had that knack about him, treated everybody the

same, and he was very well liked … he was one of the men, just like Al

Rathbone [later long-time OC of the Mortar Platoon]. He had that same

disposition.”

From Niagara to Nanaimo to Jamaica, Paterson acquired the

professionalism of soldiering and deepened his friendships with fellow

subalterns such as Alex Logie and Jack Harper. On the way to Jamaica, he

and several other Argylls met the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in

Bermuda, where the erstwhile king had been sent in the vain hope that it

would keep him out of trouble. There was time for golfing and golf was

to Bob Paterson like a muse to a poet. Paterson himself loved novels and

wrote well. His account of the Agapenor incident reads like a Graham

Greene novel. It was March 1943. Paterson and Logie, with a section each,

had been sent to act as guards on the ship after a mutiny. They were

sent to Colombia to board a flying boat dressed in ill-fitting white

suits with army boots and suitcases full of sub-machine guns, rifles,

and ammunition:

[W]e landed at Barranquilla in Colombia, spent the night there. The boys

begged me to let them [out] … the place was full of Germans. I was

terrified of them getting into trouble or something, but I let them, I

think, from oh, say, five o’clock in the afternoon until they had to

report back to the hotel at nine. And apparently they got into a

whorehouse or something, and they were just about to enjoy themselves

and the sergeant, I think, said “It’s ten minutes to nine,” and they

cursed me to beat hell and everything, and they got back. They all got

back to the hotel.But the funny part was that we went into the hotel and I went up to the

reception desk and asked about our rooms and so on, and the German –

she was a German lady, blonde hair, big – she said, before I said

anything, “Good afternoon, Lieutenant Paterson, your rooms are ready.” I

thought, “Jesus!” … [I learned years later] that same women … was

notorious, she was one of the head spies in Colombia.

While in Jamaica, Paterson had substituted for the adjutant, Capt Art

Hay, when he was absent. When Hay went to RMC in August 1942, Paterson

became the acting adjutant, and on 6 Feb. 1943, Lt Paterson became the

adjutant, an important position within the Battalion. It was a mark of

his ability, and he was promoted over a lot of other officers. Not

surprisingly, in some quarters, his appointment caused some small bit of

jealousy. But Paterson loved it: “I liked being adjutant very much … you were your own boss and well,

you answered to the Colonel obviously, but you did all the

administration. It was very busy…. The most difficult thing I ever did

in the army.”

As the Battalion prepared to go overseas in 1943, much of the work fell

to Paterson. Hay became the acting CO and things changed, and for

Paterson too:

He [Art Hay] worked the hell out of everybody. Soon as he took over the

unit … I wasn’t Bob anymore, I was Paterson – and that kind of made

me mad. He was like that … and he’d upset other people, doing other

things … I guess he worked us too hard. He really did.He’d have all the officers running up at Huntstanton, I remember.

Adjutant, anybody, we’d go out, after supper at night…. We’d worked

all day, then we’d go for a four-mile run. Jesus … he got me down. He

really did.There seems to be about [a] fifty-fifty split. Some give him [Art

Hay] credit for keeping the unit together, and others have said … it

[the officer training] was basically a pain in the ass. They said they

didn’t appreciate … sand-table schemes in the Mess, and having to keep

up the next morning.I think he was a theorist and I think he was heavy-handed. He

wouldn’t think of what we were thinking, and there was no empathy….

There was something to be done and he would draw up the operation order

– [a] brilliant operation order – but it probably was not practical

… like Haig in the First World War.

On 19 Sept. 1943, Lt Don Seldon, 2IC of C Coy, learned from “Hay … that I

am to become Adjutant and will take over from Bob Paterson in the near

future.” Shortly thereafter, the Argylls got their new CO, LCol Dave

Stewart. “I remember,” Paterson said, “ I was the Adjutant. It was

raining, and he blew in and, out of the night … ‘I’m your new CO.’

Right from the start, everybody liked him. Everybody liked him. He won

us all over in ten minutes. He had great charm and he was very decisive.

Awfully nice guy. We just thought he was great.” Stewart “appealed to

other ranks and the NCOs and the officers in quite a different way. He

seemed to sense the differences and he was a sensitive man. He knew what

I was thinking and what the other guys were thinking, and he was very

smooth.” That was Stewart the man and the leader and then there was

Stewart the CO: “I can remember his first

operation order: verbal, simple, everybody could understand it; the most

beautiful thing I ever heard. An idiot could have carried out his plan

of attack, or whatever it was, and I thought, ‘Boy, this is for me.’”

Stewart had made his mark and it was indelible. In early October, after

a bit of a handover, Seldon and Paterson traded appointments.

Maj Gordon Winfield commanded C Coy. A bully and a braggart with a

“terrific temper,” he became increasingly hesitant about command.

Increasingly, he left matters to his 2ic. The CO was also aware of

Winfield’s shortcomings and, years after the war, admitted his lack of

experience in getting rid of senior officers. “Dave Stewart asked me

before D-Day if I thought he [Winfield] could command the troops, and I

said no. Told him flatly that he could not command.” When the company

went into action, Paterson, like the other 2ICs, was left out of battle.

CSM George Mitchell of C Coy was privately scathing about Winfield’s

performance. When he was slightly wounded at St Lambert in late August,

he was sent back to England. For his part, Stewart was determined he

would never return. When the Battalion finally received badly needed

reinforcements in the early days of September, Paterson became OC of C;

Jack Harper had A, Logie had B, and Pete MacKenzie had D – a new

generation had taken over.

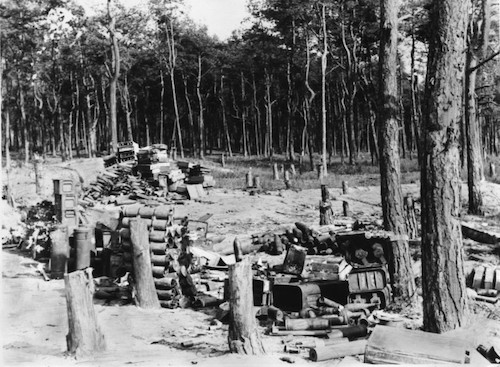

Paterson was shocked by the horror of war so evident at Falaise: “I was

stunned by the magnitude of the thing [German retreat from Falaise], the

magnitude of the dead and the horses and broken up wagons and debris

scattered all over. And the smell, we were all half sick. It was just

… horrible. I called it in the history [of the 10th Brigade] a charnel

house.”

The months of September and October leading up to the winter sojourn on

the Maas River witnessed heavy fighting and, with it, the attendant

casualties. One of the best examples of Argyll determination and

doggedness was that of C Coy at Moerbrugge (8–10 Sept). Dave Stewart had taken

over the brigade and an inept and disliked Maj Bill Stockloser took over

the battalion. The Argylls, led by C and D Coys, were to cross the canal

unsupported and without assault craft. Stockloser, when pressed by

Paterson how they were to cross without boats, described it as “a

crossing of opportunity.” The companies sustained heavy casualties,

crossing in leaking rowboats without oars. MacKenzie was wounded in the

early going and C Company was cut off by an unexpectedly fierce German

resistance. C Coy was isolated in one building. Paterson put his Bren

gunners in the upper windows and all ammunition went to them; the effect

upon the attacking Germans was devastating. On the morning of the

10th, they had run out of ammunition. By the night of the 9th,

Paterson wrote:

There was no communication by wireless or by runner. The company was

perilously short of ammunition, and had no rations. Still the whole town

was ablaze that day with small arms fire, grenades and piats. The air

was a frenzy of automatic fire and the shouts and groans of wounded

Germans. No one knows how many attacks they made, but there were many.

Their stretcher bearers worked all day and were permitted into the

company lines to clear the dead and wounded. It was the wildest show and

the bloodiest for a long time. Toward evening the enemy teed up what was

to be his last attempt at dislodging us.

C Coy held on and was prepared to fight on. Bob Paterson had said he

would have been happy to stay in Jamaica for the war or for a successful

Stauffenberg plot end the war and the necessity for fighting. This

quiet, reflective man, given to poetry and novels, had no intention of

giving up:

I had thirty men, and they were all there. You didn’t have to give any

orders. They were going to fight, they were all going to fight…. Never

thought of [surrendering]. Never entered my mind. Didn’t enter [CSM]

Mitchell’s mind. Didn’t enter any of the men’s minds, that I know of …

I thought that was the end…. [But] I think I was too exhausted to be

afraid … I was fatalistic at that point. I’m no hero. I was no hero at

all … there were no heroics in my mind. I was beyond that point.

Happily, in the early morning hours of the 10th, the RCE bridged the

canal and shortly afterwards the tanks of the South Alberta Regiment

crossed and relieved the besieged company: “You could hear the [SAR]

engines start up,” Paterson remembered, “and we knew they were

coming. And Jesus, what a glorious moment, I’ll tell you.” A month or so

later, several Argylls, including the CSM, were awarded medals for this

action but not Paterson. His 2IC, Capt Sam Chapman, commented in a letter

home: “But Paterson was the man who decided they’d stay + fight to the

last man – if it came to that – which decision in my opinion required

more guts than all sorts of spectacularly brave acts.”

The fighting, the casualties, the isolation from brother officers, the

death of Alex Logie on 20 Oct. 1944, and the lack of reinforcements took

their toll on Bob Paterson in the days leading up to early November.

Then, LCol Stewart left and Stockloser was in charge again. Paterson had

had it: “You were just exhausted … to hell with the booze and

women.” He was equally tired of leadership at higher levels: “Shit, you

didn’t have a hope in hell. And I was very critical as I went on, and I

got worse. The longer I was in the line, the worse I felt about the

goddamn command set-up … I gave up trying to be logical after a

while.” Had he been certain of Stewart’s return, he could not have

left. On 19 November, Sam Chapman wrote to his wife: “Major Paterson just

got word that he is going to brigade on staff. He’s seen a lot of

fighting and deserves a break – anybody who’s been lucky that long

shouldn’t try his luck too far.” For his part, “I was seconded, but I

left to all intents and purposes … I couldn’t take it any more. I was

having convulsions at night … and I couldn’t stand up straight…. And

I was terrified of doing that in front of the men, and I didn’t tell

anybody … so I applied for a staff posting…. I had lost all my pals:

Logie, Harper, everybody I knew gone, except Pete. Pete Mackenzie came

back. I’d lost anybody I knew. Johnny Farmer’d gone, Coons had gone.”

Bob Paterson was with the 10th Brigade until the end of fighting. He

returned to the Argylls as a company commander and participated in

several of the celebrations. Given the task of writing the history of

the 10th Brigade, he penned a short, incisive, and eloquent chronicle.

He returned home, moved to Brantford, Ontario, where he opened a business, had a

home backing on to a golf course (his idea of heaven), married Peggy,

and had two sons: Robert Alexander and Ian. His sister, Janet, married

Hugh Maclean.

Like Logie and Maclean, he, too, would be remembered with respect by his

men. A private in C Coy, John Evans (in the lower right of the famous

picture of Maj Dave Currie winning the VC at St Lambert), was a crusty,

disagreeable commissioner at the Armouries, a man seemingly incapable of

the slightest gesture of respect to anyone regardless of rank. At a mess

dinner in the late 1980s, Maj Paterson was walking in and passed Evans,

who snapped to attention and saluted. While they chatted briefly, Evans

remained at attention and saluted again when Paterson departed. “Best

damn officer I ever served under,” Evans snorted to no one in particular

and then reverted to his churlish ways. Paterson was a fine officer and,

like Logie and Maclean, an equally decent man with a sharp intelligence

and genuine modesty.

When, in 1986, Claude Bissell was interviewed, he began by reading the

last two paragraphs of Paterson’s history of the 10th Brigade. They

had, Bissell thought, a “symphonic” quality and expressed perfectly how

soldiers in battle felt. Paterson was explaining why, when huge crowds

in the major cities of the Western world greeted news of the war’s end

with rejoicing, soldiers in the field of battle were mute. On 27 April,

he wrote to Phyllis Logie: “We are being sporadically shelled, our guns

and rockets startle the beautiful spring nights. It’s all madness, a

fantasy. Each day we say to-morrow – and yet it’s still to-morrow.”

That understanding informed the last paragraph of his history, and those

words inspired the title of Black Yesterdays: The Argylls’ War:

Perhaps in the months to come will that fabulous “to-morrow” really be

to-day – a day when all the bells and voices of our great memories

shall ring out, cry out, peal, and shout, in one wild tumultuous song

of thanksgiving. Sometime, while dreaming over a sun drenched lake,

while pausing in the fields to watch the summer clouds pile one upon the

other, or in the quiet half hour before sleep, we shall hear that

symphony we once listened for, and it shall swell and reverberate

through our beings in unforgettable strength and beauty so that we shall

know that to-day has come, and that those black yesterdays are

forever left behind.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian