The 91st Regiment Canadian Highlanders’ Service with the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), CEF

Pre–First World War beginnings: The 91st Regiment march past before HRH The Prince of Wales at the Quebec Tercentenary, July 1908. Argyll Museum and Archives.

Pre–First World War beginnings: The 91st Regiment march past before HRH The Prince of Wales at the Quebec Tercentenary, July 1908. Argyll Museum and Archives.

By David G. Morgan

INTRODUCTION

One hundred and thirty-one individuals from Hamilton’s 91st Regiment Canadian Highlanders embarked for overseas service with the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), CEF, in September 1914. Some 80 percent of them became casualties during 1915, and very few individuals remained on strength with the 16th Bn after the Battle of the Somme in late 1916. As the 16th Bn did not receive any reinforcement drafts from Hamilton after its formation, the original Hamilton contingent was, in a sense, orphaned, and quickly depleted. During the course of the war, 28 individuals were killed in action or died of wounds, and at least 75 were wounded, several more than once. Others were struck off strength due to chronic illness. In the interest of brevity, this narrative mainly focuses on the experiences of the original five officers and five senior NCOs of the Hamilton contingent. It relies heavily on information gleaned from their CEF personnel records and also on The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914–1919. The author, Col Hugh Urquhart, DSO and bar, MC, CdeG(F), a pre-war officer from the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada who served in the 16th Bn, wrote this masterful history after the war, based on his personal observations and experiences on the Western Front.

Image 4: 91st soldiers attend annual summer training at Niagara Camp, 1906. Source: Argyll Museum and Archives.

Image 4: 91st soldiers attend annual summer training at Niagara Camp, 1906. Source: Argyll Museum and Archives.

MOBILIZATION AT VALCARTIER, QUEBEC

The hastily constructed tent camp at Valcartier was the birthplace of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. In late August 1914, volunteer contingents from across Canada assembled to be formed into the 1st Canadian Division for overseas service.

Contingents from four highland regiments of the Non-Permanent Active Militia would form what was to become the 16th Bn (Canadian Scottish). These included: 234 all ranks from the 50th Regiment (Gordons) of Victoria; 536 all ranks from the 72nd Regiment (Seaforths) of Vancouver; 248 all ranks from the 79th Regiment (Camerons) of Winnipeg; and 137 all ranks from the 91st Regiment (Canadian Highlanders) of Hamilton.

The 91st Regiment (hereafter the Hamilton contingent) arrived at Valcartier on 23 August 1914 after a 23-hour train ride. Their arrival was perhaps anti-climactic. The train “was switched to a military siding and came to a stop on a stretch of pasture land in the midst of the bush” (Urquhart, p. 13). The Hamilton contingent was both the first to arrive and the smallest of the four Highland contingents. Maj Henry Roberts was the officer in charge, and his second in command was Capt Frank Morison. They were accompanied by Lieutenants Henry Duncan, Paul Powis, and Alexander Colquhoun. The ranking NCO was C/Sgt George Mitchell. Four other sergeants rounded out the senior NCO roster: John Stewart, George Slessor, John Cochran, and John Steele. The Hamilton contingent climbed down off the coaches, formed up, and prepared to march into history.

Image 5: The 91st Highlanders Contingent at Camp Valcartier. In the photo are 82 members of the original 152 sent to the 16th Bn. The soldier on the far left, standing, in trews and a Glengarry is actually a Seaforth medic. The man standing to his immediate left is C/Sgt George Mitchell, who was KIA sometime between 18 and 22 May 1915 at Festubert. His body was never recovered. Source: Rembrandt Studios, Winnipeg. Photographer unknown, courtesy of Steve Clifford.

Image 5: The 91st Highlanders Contingent at Camp Valcartier. In the photo are 82 members of the original 152 sent to the 16th Bn. The soldier on the far left, standing, in trews and a Glengarry is actually a Seaforth medic. The man standing to his immediate left is C/Sgt George Mitchell, who was KIA sometime between 18 and 22 May 1915 at Festubert. His body was never recovered. Source: Rembrandt Studios, Winnipeg. Photographer unknown, courtesy of Steve Clifford.

The 16th Bn was officially stood to on 2 September 1914. There was little uniformity. Each contingent turned out in different tartans, head dress, cap badges, and orders of dress. The Hamilton contingent’s Balmoral bonnet set them apart from the others, who wore various patterns of Glengarries. Consequently, they were called the Harry Lauders after a popular Scottish singer of the time.

When the contingents marched into camp, the only one completely equipped for the Field was the Cameron contingent. It was fitted out in active service order – web equipment, sun helmets, etc… The 50th (Gordons) contingent was completely clothed in the Gordon uniform and partially fitted with the Oliver (leather) equipment; the 91st contingent was much the same; but the Seaforths, that is the rank and file, because of their large number, had little uniformity of dress (Urquhart, p. 16).

Indeed, some of the Seaforths initially paraded in civilian clothes and cowboy hats.

Col Urquhart wryly observed that the 16th Bn was composed, roughly speaking, of Scotsmen and gentlemen. Some 40% were born in England, while 36% came from Scotland. The numbers in the Hamilton contingent were very similar. Only 23% of them were born in Canada, mostly in the Hamilton area. Some 77% were recent immigrants: 39% from England, 24% from Scotland, 2% from Ireland, and 2% from the United States of America. Of the Scots, many had family ties to Glasgow and surrounding counties, perhaps reflecting immigration patterns in the Hamilton community (Urquhart, p. 16).

The 16th Bn at Valcartier was initially organized following the pre-war British War Office Table of Organization and Equipment (TOE) for colonial infantry battalions, which included a battalion HQ and support section, Army Medical Corps section, machine-gun section, transport section, eight rifle companies lettered A to H, and an administrative base company. The transport section also carried a number of signallers on strength. It mustered 46 officers and 1,116 other ranks, with a total strength of 1,162.

The Hamilton contingent provided 131 all ranks. Of these, 117 were assigned to F Coy, initially under command of Capt Morison, who signed virtually all of the Hamilton contingent’s attestation papers. Maj Roberts was assigned to Bn HQ as Junior Major, a staff position. Lt Duncan was appointed one of the three platoon commanders. C/Sgt Mitchell was the senior company NCO. Five other ranks were assigned to the transport section, including two signallers. One private was assigned to B Coy and four privates were assigned to E Coy. Lieutenants Powis and Colquhoun and a private were assigned to Base Coy. With these departures, F Coy was brought back up to strength of 131 all ranks with the influx of a number of Seaforths, including two platoon commanders.

There are some discrepancies with the Hamilton numbers. Col Urquhart cites 91st Regiment records, which state there were 151 other ranks in the Hamilton contingent, reduced at Valcartier by rejections of the medically unfit and transfers to other units. He then cites 5 officers and 132 other ranks for a total of 137 all ranks. However, the 16th Bn 1915 CEF nominal roll (often referred to as the sailing roll) lists 5 officers and 127 other ranks for a total of 131 all ranks present from Hamilton in the 16th Bn when it sailed for England. In the absence of earlier nominal rolls, it appears that the sailing roll is the more accurate accounting and it also identifies individuals by name and regimental number. Thus, the Hamilton contingent’s 131 all ranks accounted for approximately 12% of the 16th Bn’s total strength of 1,162 all ranks.

Under Sir Sam Hugh’s improvised and chaotic mobilization scheme, the 91st Regt was tasked with providing a single company, while the Seaforths were tasked with providing two companies (a so-called double company), but their initial contribution of over 500 troops far exceeded that requirement. Consequently, one cannot underestimate the Seaforth influence on both the 16th Bn at large and the Hamilton contingent in particular. The Seaforths provided more than half of the initial officers and almost half of the troop strength of the 16th Bn. According to Col Urquhart’s tally, they filled most of the officer and senior NCO appointments, including: commanding officer, deputy commanding officer, officers commanding two rifle companies, adjutant, signals officer, transport officer, machine gun officer, quartermaster, medical officer, regimental sergeant major, pipe major, drum major, armourer sergeant, signals sergeant, shoemaker sergeant, acting pay sergeant, machine gun sergeant, pioneer sergeant, cook sergeant, medical sergeant, and postal corporal. As we shall see, this had a direct impact on the military aspirations (and in one case, the personal life) of individuals from the Hamilton contingent.

The 16th Bn spent only 25 days at Valcartier. They were deficient in equipment and, by later standards, the training was rudimentary. However, most had previous service in the British Army, Territorial Army, and the Canadian Army, including mostly the NPAM. Some were veterans of the Boer War. “But what always must be remembered is that the officers and men of the 1st Canadian Division were in most instances trained, according to pre-war standards, before they reached [Valcartier] camp, especially in the understanding of that word ‘duty’” (Urquhart, p. 17).

SALISBURY PLAIN, ENGLAND

The 16th Bn embarked on the H.M.T.S. Andania, a 13,000-ton Cunard ocean liner, arriving at Devonport near Plymouth, England, on 15 October 1914. Any remaining delusions that the war would be over by Christmas were soon replaced by the cold reality of an abysmal winter, inadequate quarters, and widespread sickness. The official history notes that the Canadians’ stay on Salisbury Plain coincided with a period of abnormally heavy precipitation. It rained on 89 out of 123 days. During October to February, the rainfall totalled 60 centimetres, almost double the 32-year average.

The 16th Bn’s first bivouac area was a tent camp at West Down South, located in a shallow, poorly drained depression that quickly became a sea of mud. At the end of November, they were moved to somewhat higher ground at Lark hill Camp, 2.5 kilometres north of Stonehenge, and quartered in hastily constructed, uninsulated wooden huts. Training was compromised by winter gales, heavy rain, and large numbers on sick parade. Sleet and fog hampered range practice due to limited visibility. Influenza, bronchitis, and pneumonia abounded. In some cases, pre-existing conditions like arthritis became debilitating in the damp and cold. Work parties involved in the construction of camp infrastructure and huts further upset training schedules. The official history notes that approximately 25% of the 4,000 admissions to hospital were cases of venereal disease.

Image 6: Canadian troops lived in appallingly wet conditions on Salisbury Plain, 1915. Source: Department of National Defence.

Image 6: Canadian troops lived in appallingly wet conditions on Salisbury Plain, 1915. Source: Department of National Defence.

To conform with evolving British Army practice, the 16th Bn was reorganized on the double company system. The number of rifle companies was reduced by half and numbered 1 to 4. Under this TOE, each rifle company had an authorized strength of 227 all ranks and consisted of a HQ and four platoons of 50 all ranks. Each platoon contained four sections of 12 soldiers. F Coy was absorbed into No.3 Coy, organized as a joint Seaforth/Hamilton unit. Here, too, the Seaforths predominated. Capt Cecil Merritt, a Seaforth officer, was appointed officer commanding, and Captain Morison became the company’s second in command. The CSM and CQMS were both Seaforth NCOs, while three of the four rifle platoons were commanded by Seaforth subalterns. The exception was Lt Duncan, appointed platoon commander of No.12 platoon. C/Sgt Mitchell reverted in rank to sergeant and became a platoon sergeant.

By early 1915, even before the 16th Bn landed in France, the Hamilton contingent was reduced in strength. Ten individuals were deemed medically unfit and returned to Canada. Five other individuals were transferred from the 16th Bn to other non-infantry corps. Major Henry Roberts transferred to the British Army. Five individuals were transferred to the 13th Bn CEF and one to the 4th Bn CEF for service in France. That left 114 all ranks of the original 131 Hamilton contingent when the 16th Bn marched out of Lark Hill Camp for France on 11 February 1915.

The story of the Canadians on Salisbury Plain, however, relates to a sterner reality than the routine of training. They had to fight a struggle against almost intolerable conditions of weather, sickness, and an official distrust which branded them as undisciplined and ineffective (Urquhart, p. 30).

As the 1st Canadian Division gained experience at the front in the coming months, this dismal assessment was proven to be unfounded. Ultimately the Canadian Corps matured into one of the most effective Allied formations on the Western Front.

FIRST CASUALTIES: FLEURBAIX TRENCHES, 4–24 MARCH 1915

On 4 March 1915, following a brief familiarization with trench warfare near Armentiers, the 1st Canadian Division relieved the 7th British Division near Fleurbaix and occupied a 6,000-metre frontage of trenches. This move was in preparation for the first British offensive of 1915 at Neuve Chapelle 10-12 March. On the first day in the line, the 16th Bn suffered its first fatality to enemy action. Although not directly involved in the ill-fated British offensive, the 1st Canadian Division played a supporting role by firing upon German positions.

On 14 March 1915, 15 days short of his 24th birthday, Pte Stephen Ritchie became the first of the Hamilton contingent to die in action. An unmarried blacksmith’s helper, he was born in Scotland and had emigrated with his parents to Hamilton before the war. His remains were buried in the Rue Petillion Military Cemetery, located six kilometres southwest of Armentiers. The circumstances of his death were not recorded.

The three-week period in the Fleurbaix trenches was the 16th Bn’s baptism of fire. Although considered a quiet sector, sniper and artillery fire killed eight and wounded another eight. During this time, the Hamilton contingent suffered three killed in action and one wounded.

YPRES SALIENT: 16 APRIL 1915–4 MAY 1915

The description of what the Salient was, and what it meant to its defenders, has been told and retold, but none can understand the nightmare of its approaches and front line except those who, when it was in one of its fierce moods, entered its portals night after night or who, duty bound, stood on guard at the rim of that hollow of death or in the long hours of darkness (Urquhart, p. 124).

The 16th Bn held a section of trenches near the small Belgian village of St Julian in the Ypres Salient during a four-day period, 16–20 April 1915. During this time, the Hamilton contingent suffered two wounded in action.

During the period 22 April to 4 May 1914, the 16th Bn experienced heavy fighting during the Second Battle of Ypres. German forces attempted to reduce the Salient, the last Allied toe-hold in Belgium, and capture the cloth-manufacturing town of Ypres, an important transportation hub. German possession of Ypres would have threatened communication with the British-held Channel ports. This battle will always be remembered for the German introduction of poison gas as a weapon of war – catching the Allies completely unprepared. Such marginally effective field expedients as urinating into handkerchiefs and field dressings to neutralize the chlorine gas were first employed, but it would take several months until the effective small-box respirator was developed. The Second Battle of Ypres was also notable for the number of debilitating head wounds from shrapnel, and several months would pass before the iconic Brodie steel helmet was issued.

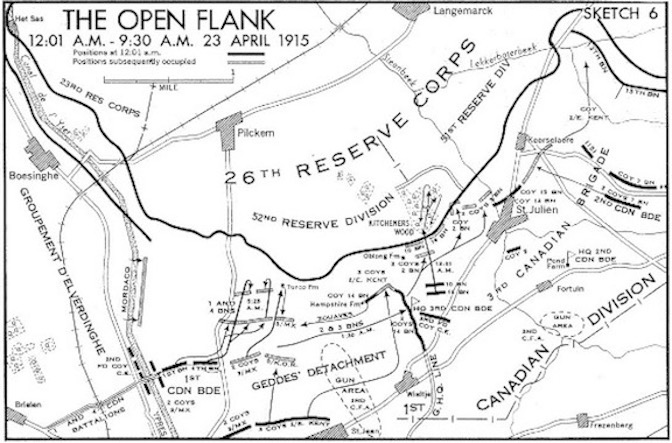

Image 7: The 16th at Kitchener’s Woods. Source: Department of National Defence.

Image 7: The 16th at Kitchener’s Woods. Source: Department of National Defence.

To help close the six-kilometre gap that the German attack had opened earlier in the day, the Canadians were ordered to secure an oak plantation known as Kitchener’s Wood, approximately four kilometres northeast of Ypres. During the night and early morning hours of 22–23 April 1914, the 16th Bn supported the 10th Bn in the counter-attack – the first major offensive operation of the 1st Canadian Division. The two battalions formed up one behind the other on a two-company frontage in eight ranks, dropped their packs, fixed bayonets, and at 23:46 hours advanced into the darkness. There had been no time for reconnaissance. At some 150 metres from the woods, the leading troops unexpectedly hit a wire fence. In smashing it down with their rifle butts, they alerted the German defenders, who illuminated the area with flares and opened a heavy volume of machine gun fire into the dense ranks. The two battalions, suffering heavy casualties, stormed the woods and drove the enemy out in confused close-quarter fighting. The action had temporarily stabilized the Allied line at the apex of the Ypres Salient, yet the triumph proved short-lived. Within 48 hours, German forces had re-taken the woods. During this battle, the 16th Bn suffered 162 all ranks killed, 246 all ranks wounded, and 31 all ranks lost as prisoners, totalling 439 casualties. The attack on Kitchener’s Wood was the single most costly action the 16th Bn fought during the entire war. The Hamilton contingent suffered 8 killed in action and 25 wounded.

BATTLE OF FESTUBERT: 18–20 MAY 1915

Although in after years some of those who were present then with these units witnessed many desolate battlefields, yet none surpassed in grimness the scene they saw that morning at Festubert. It is true that later in the war, especially at the Somme and Passchendaele, the artillery battered buildings, villages and the earth itself into an unrecognizable pulp, but the completeness of this mutilation often served to cover up the human side of the tragedy, which at Festubert stood revealed in all its nakedness. Smashed rifles, torn, bloodstained equipment and clothing were strewn over the battlefield. The dead, mainly British, lay thick around. They were scattered amongst the multi-coloured bags, black, blue, gray and white, of the breastwork, thrown broadcast by the bombardment (Urquhart, p. 78).

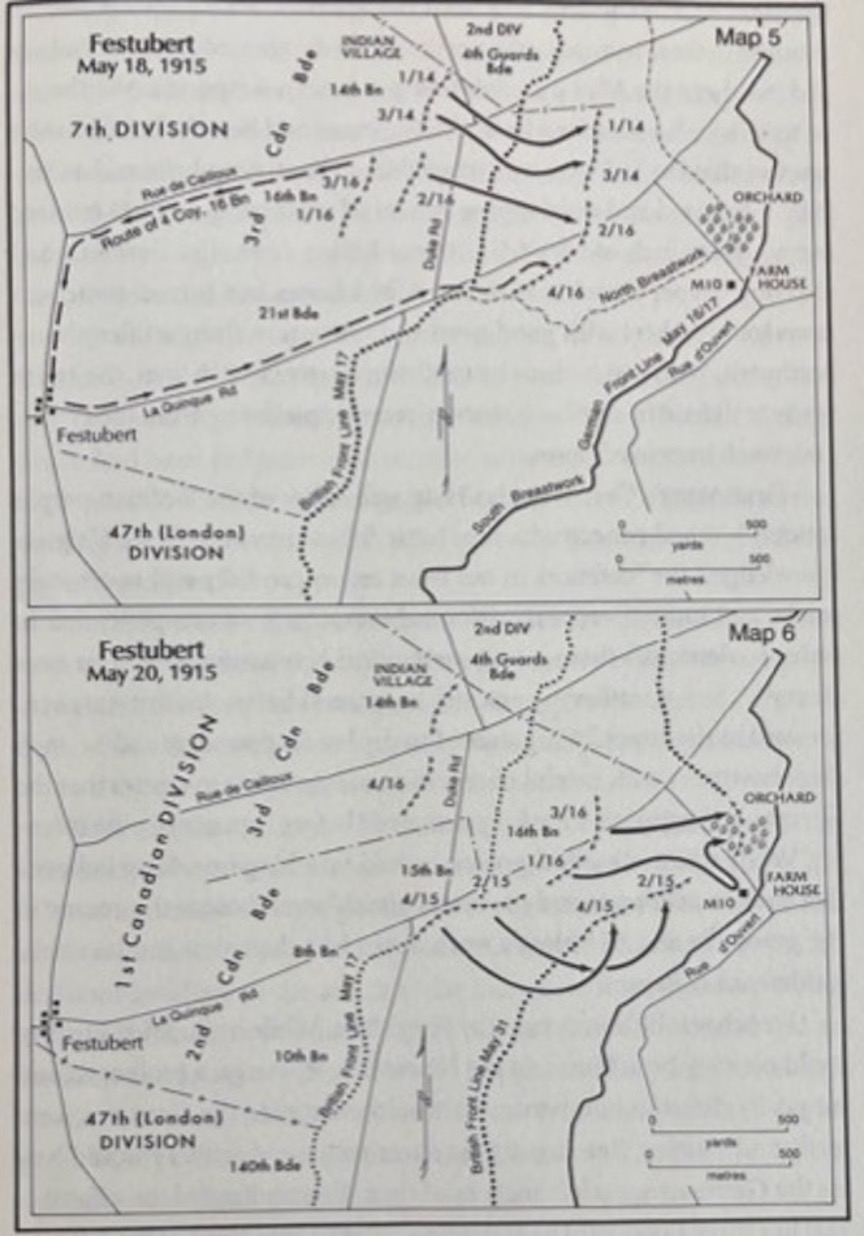

Image 8: The Battle of Festubert. Source: Brave Battalion by Mark Zuehlke, 2008.

Image 8: The Battle of Festubert. Source: Brave Battalion by Mark Zuehlke, 2008.

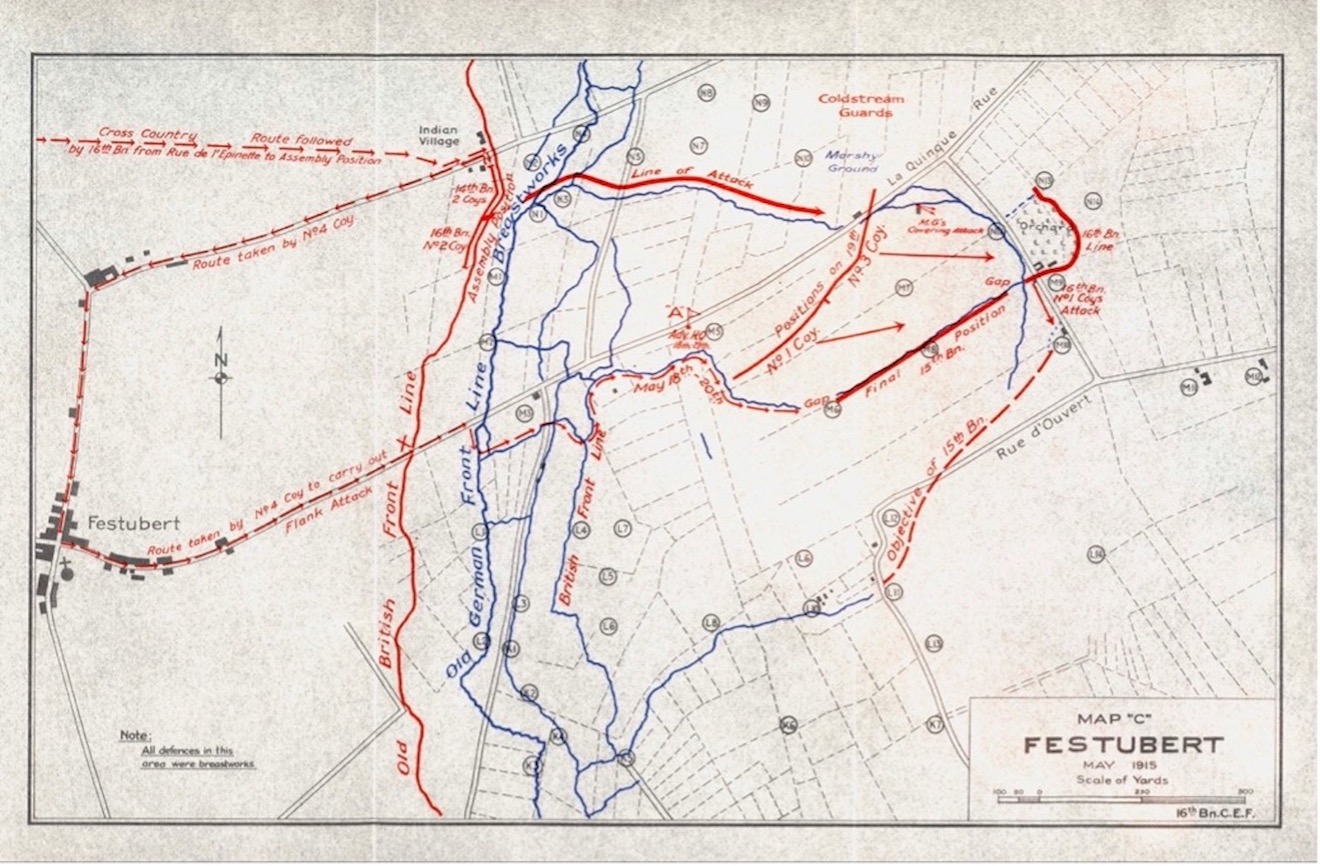

Image 9: Festubert. Source: Urquhart, Hugh. The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1932).

Image 9: Festubert. Source: Urquhart, Hugh. The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1932).

As badly mauled as the 16th Bn was after 2nd Ypres, they did not have long to recuperate. They marched some 30 kilometres south of Ypres to the Bethune area and reorganized. Following stalemate at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915, and the Battle of Aubers Ridge on 9 May 1915, the British high command selected the Festubert area, directly south of the Aubers Ridge, for the next great push against the German lines. Due to the high-water table, the largely flat and featureless ground was criss-crossed by drainage ditches and hedgerows. Even shallow trenches soon flooded defensive breastworks, and isolated outposts constructed of sandbags were erected above ground. The Festubert offensive had limited tactical objectives but was designed to hold and deplete the German defenders.

The 16th Bn’s main objective was the capture of a feature called Canadian Orchard. On the afternoon of 20 May 1915, two companies captured this feature in the face of heavy small arms and artillery fire. During this battle, the 16th Bn suffered 71 killed in action and 206 wounded. Of this, the Hamilton contingent suffered 10 killed in action and 20 wounded.

GIVENCHY AND PLOEGSTEERT: JUNE 1915–MARCH 1916

Following the Battle of Festubert, the 16th Bn moved a few kilometres south to the Givenchy area, where they rotated through the front line and brigade and divisional reserve for rest and training. Lennox tartan kilts were issued to the pipers, and khaki kilts for the rest of the Bn. On 12 June 1915, the problematic Ross rifle was replaced with the Lee Enfield rifle throughout the Canadian 1st Division.

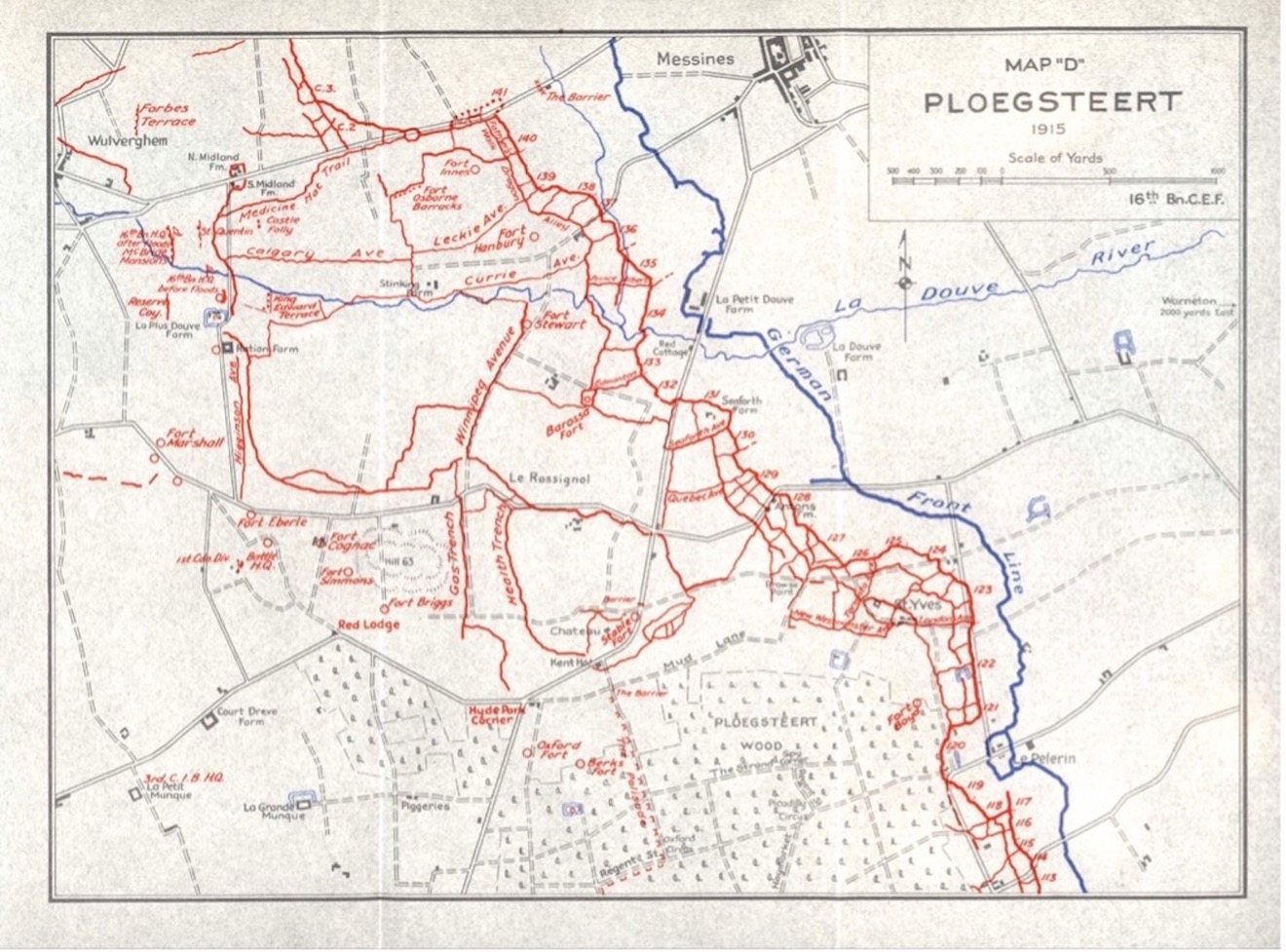

In late June, the 16th Bn moved to the Ploegsteert area, where it remained for the remainder of the year and into the first three months of 1916. Although a relatively quiet sector, the 16th Bn lost 51 killed in action and 139 wounded during this ten-month period. The Hamilton contingent suffered one individual wounded in action during May 1915 while holding the trenches in the Festubert sector and one other wounded later in the year when holding trenches in the Pleogsteert sector.

By the end of 1915, the Hamilton contingent had suffered 21 killed in action and 50 wounded, totalling 71 casualties or 62% of the 114 all ranks who had landed in France in February 1915. Of the 50 wounded, 23 individuals were repatriated to Canada during late 1915 or early 1916 because of debilitating wounds or chronic illness. Others were administratively transferred to other corps or reserve battalions in England owing to chronic health issues or lower medical categories. Thus, the Hamilton contingent ended the year severely depleted, having lost some 80% of its effective strength.

Image 10: Ploegsteert. Urquhart, Hugh. The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1932).

Image 10: Ploegsteert. Urquhart, Hugh. The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1932).

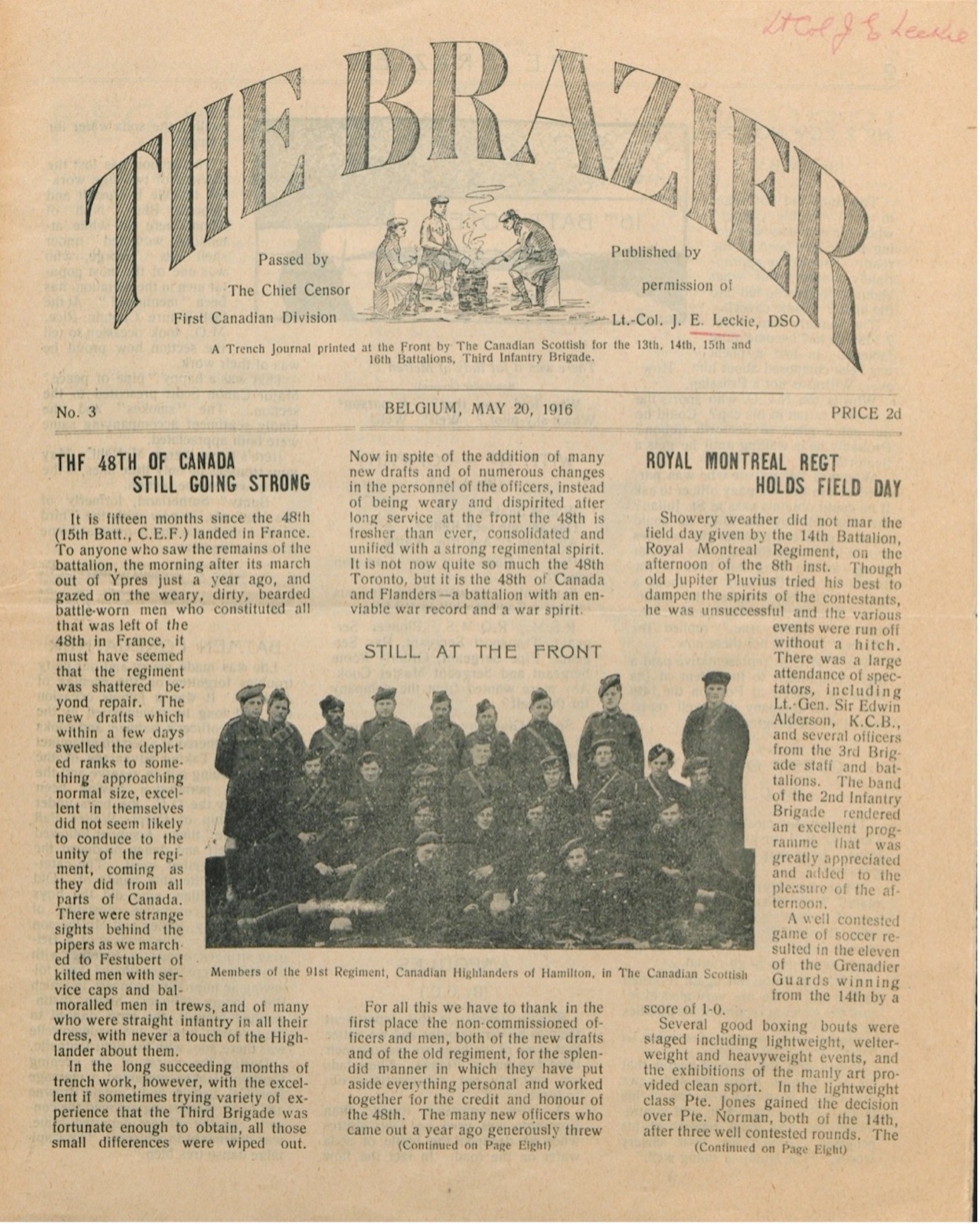

1916: STILL AT THE FRONT

The 16th Bn remained in the Ploegsteert area until the end of March 1916 when it returned to the Ypres Salient. During this period, the first steel helmets and canvas “gas helmets” were issued. In the words of the official historian, the CEF’s role was “stationary yet aggressive.” In the 20 May 1916 edition of the 16th Bn’s trench newsletter the Brazier, a front-page photo captioned “Still at the Front” showed 25 original members of the Hamilton contingent that were still serving in France. This included Lt. Powis, recently arrived from Base Coy in England. The photo appeared to commemorate a reunion of sorts as not all were still serving in the 16th Bn. Two were in the Canadian Signal Corps Canadian Engineers (CSCCE), two in the Canadian Machine Gun Corps (CMGC), and one was with the Canadian Military Police Corps (CMPC). Nonetheless, by the end of 1916, two of these individuals would be killed in action and seven wounded.

During the 28 March–31 May period, the 16th Bn held trenches in the Ypres Salient – Bluff to Mt Sorrel sector. During this time, the Hamilton contingent suffered one killed in action and one wounded in action. During the 3–7 June 1916 period, the 16 Bn was in support of an attack at Mount Sorrel, where the Hamilton contingent suffered two wounded in action. From 12 to 14 June 1916, the 16th Bn participated in the Battle of Mount Sorrel, where the Hamilton contingent suffered two more wounded in action. Total Hamilton contingent casualties during this period were two killed in action and seven wounded.

The big show on the Western Front in 1916 was the Battle of the Somme, launched on 1 July along a 34-kilometre front. The aim was to relieve pressure on the French at Verdun. Misplaced optimism of a general breakthrough of German lines was shattered on the first morning when the BEF lost some 60,000 casualties, 20,000 of them fatal. The preceding week-long artillery barrage had failed to destroy the German defences, particularly their machine gun posts, which decimated the densely packed formations of advancing British infantry. It devolved into a four-month battle of attrition in which the Germans suffered 650,000 casualties, the British 420,000, and the French 195,000; it became synonymous with the futility of trench warfare. The Canadian Corps was not engaged in the early fighting but was ordered to relieve the 1st Anzac Corps starting on 30 August 1916 near Pozieres.

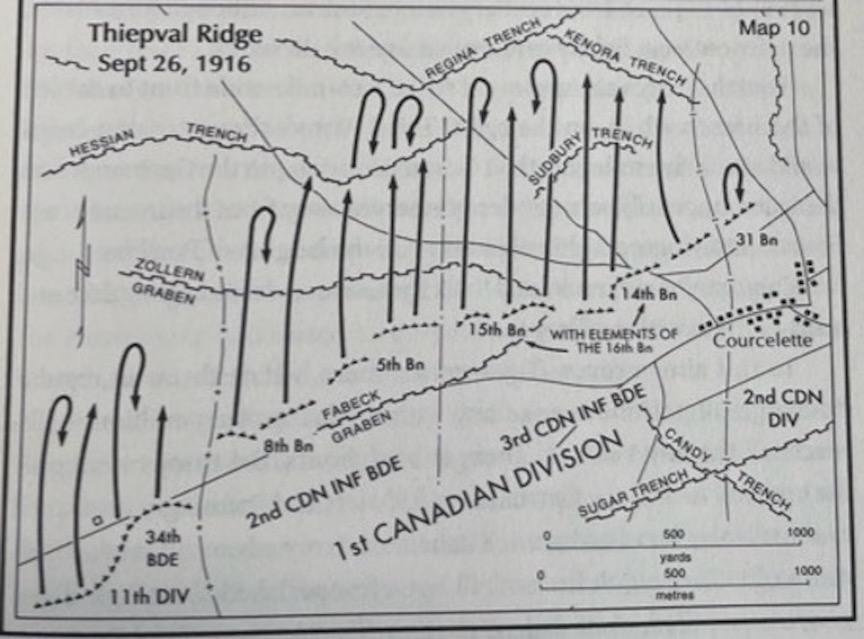

In late August 1916, the 16th Bn moved to the Somme area with the 1st Canadian Division, where it participated in three actions. During the 3–7 September 1916 period, it fought a bloody holding attack at the Moquet Farm at Pozieres. This cost the Hamilton contingent three killed in action and one wounded. During 19–28 September 1916, the 16th Bn supported the attack on Thiepval Ridge (Kenora Trench), which cost the Hamilton contingent one killed in action and two wounded. Finally, during the 7–9 October 1916 period, during the attack on Ancre Heights (Regina Trench), the Hamilton contingent suffered two wounded in action.

Image 11: The actions at Regina and Kenora trenches on the Somme. Source: Brave Battalion by Mark Zuehlke, 2008.

Image 11: The actions at Regina and Kenora trenches on the Somme. Source: Brave Battalion by Mark Zuehlke, 2008.

After a month of intense fighting at the Somme, the 16th Bn had lost a staggering 877 casualties, including 328 killed in action, 523 wounded, and 26 prisoners of war. This included 26 officers, of whom ten were killed. The mud-caked survivors of the 16th Bn trudged away from the Somme on the morning of 11 October 1916, barely mustering an under-strength company. The battalion would have to be rebuilt virtually from scratch. Of this the Hamilton contingent lost four killed in action and five wounded, indicative of how few remained in the ranks by late 1916.

The part which a battalion played in the midst of those weighty contending forces was insignificant. Tactically little need be said to describe it. The men marched in over shell swept roads; they waited patiently in the shelled trenches; they advanced a few hundred yards in the “limited objective” attacks, with barrages in front of them; if fortunate they held their position with heavy casualties; if not, they came back – or such as remained – to their jumping-off trench and had still heavier losses; and they returned to rest billets a shadow of their former selves (Urquhart, p. 162).

By the end of 1916, the Hamilton contingent was a shadow of its former self. During 1916 it had suffered a total of six killed in action and 11 wounded. In addition, three other individuals were administratively transferred to other units due to chronic illness or lowered medical categories. Thus, with the loss of 20 individuals the Hamilton contingent was left with only a handful serving in the ranks during the next two years of the war. Some had returned to the ranks after recuperating from earlier wounds or illnesses. However, without access to the Part II Battalion Orders (unfortunately, Library and Archives Canada has not digitized these and they are not available online), it is difficult to trace the exact numbers of the Hamilton contingent still serving with the 16th Bn; nevertheless, there were a few.

Image 12: 16th Battalion trench newsletter with an image of members of members of the 91st. This photo includes surviving members of the 91st as well as several who transferred to other Corps but somehow returned for a bit of a reunion. Source: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06780_3/1

Image 12: 16th Battalion trench newsletter with an image of members of members of the 91st. This photo includes surviving members of the 91st as well as several who transferred to other Corps but somehow returned for a bit of a reunion. Source: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06780_3/1

16th Bn Hamilton Contingent

Individuals from left to right in the above “Still at the Front” photo, published in the 20 May 1916 edition of the Brazier newsletter, are:

Lying Down:

Pte Arthur Ridley, transferred to 9th CIB HQ 05 Feb 1917, Demob 1919?

Pte (Cpl) Charles Payne, Demob 09 Mar 1919.

First Row:

Pte James Niven, WIA 02 May 1915 (Ypres), Demob 22 Mar 1919

Sgt James Gemmel, WIA 22 Apr 1915 (Ypres), WIA 27 Sep 1916 (Somme, Thiepval Ridge – Kenora Trench), KIA 28 Jul 1918 (Telegraph Hill Sector)

Pte (Sgt) Robert Taylor, WIA 13 Jun 1916 (Battle of Mount Sorrel), Demob 25 May 1919

Cpl (CQMS)William Stokes, WIA 20 May 1915 (Festubert), WIA 13 Jun 1916 (Battle of Mount Sorrel), Demob 04 Jul 1919

Pte Alexander Barr, Demob 29 May 1919

Pte William Ryder, transferred to CMGC 09 Mar 1916, Demob 05 May 1919

Second Row:

L/Cpl (Sgt) Walter Vyse, Demob 07 Mar 1919

Pte (Cpl) James Campbell, WIA 29 Apr 1917 (Willerval), Demob 09 May 1919

Pte Archibald Johnston, WIA 18 May 1915 (Festubert), transferred to CASC 19 Jul 1916, Demob 1919?

Lt Paul Powis, WIA 09 Aug 1916 (Hill 70 Front – trenches), Demob 16 Dec 1919

Pte Edward Galligher, WIA 22 Apr 1915 (Ypres), WIA 15 Aug 1917 (Battle of Hill 70), transferred to CMGC 10 Oct 1918, Demob 1919?

Pte Fred Taylor, WIA 13 Jun 1916 (Battle of Mount Sorrel), Demob 01 Nov 1918

Cpl William Treyise, KIA 18 Jul 1916 (Ypres Salient – trenches)

Pte Albert Ritche, WIA 06 Jun 1916 (Battle of Mount Sorrel), Demob 31 Aug 1917

Third Row:

Cpl George Uri, (SIGS) WIA 26 Sep 1918 (Canal du Nord)

Pte (Cpl) John Ford, transferred to CMGC 28 May 1917, Demob 13 Mar 1919

Pte P. Mungo (unidentified)

Cpl Alexander McMillan, WIA/POW 01 Oct 1918 (Canal du Nord – Cuvillers), Demob 29 Dec 1919

Pte Arthur Foord, transferred to CMPC, Demob 04 Nov 1919

CQMS James Boyes, KIA 08 Oct 1916 (Somme Ancre Heights – Regina Trench)

Sgt (CSM) John Newton, Demob 25 May 1919

Cpl (Sgt) William Jackson WIA/POW 01 Oct 1918 (Canal du Nord – Cuvillers), Demob 23 Mar 1919

Pte Albert Hamilton, WIA 05 Jun 1916 (Mount Sorrel), transferred to CFC 20 Mar 1918, Demob 13 Aug 1919

LAST CASUALTIES: 1918

L/Cpl John Hall was the last of the Hamilton contingent to be killed in action, on 11 August 1918, during the last day of the Battle of Amiens. He was born in England in January 1882 and had emigrated to Hamilton before the war. He was single and worked as a butcher. His notable tattoo collection included, among others, a horse and trumpeter on his chest and the Prince of Wales on his right arm. He was previously wounded by a shrapnel ball in the right knee on 22 April 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres. He had served in various reserve units while recovering in England and rejoined the 16th Bn in France in late August 1917. He was killed instantly by shell fire while standing to with his company in a support line southeast of Rouvory during a heavy enemy bombardment. His remains were buried in the Rosieres Communal Cemetery Extension. He was 36 years old.

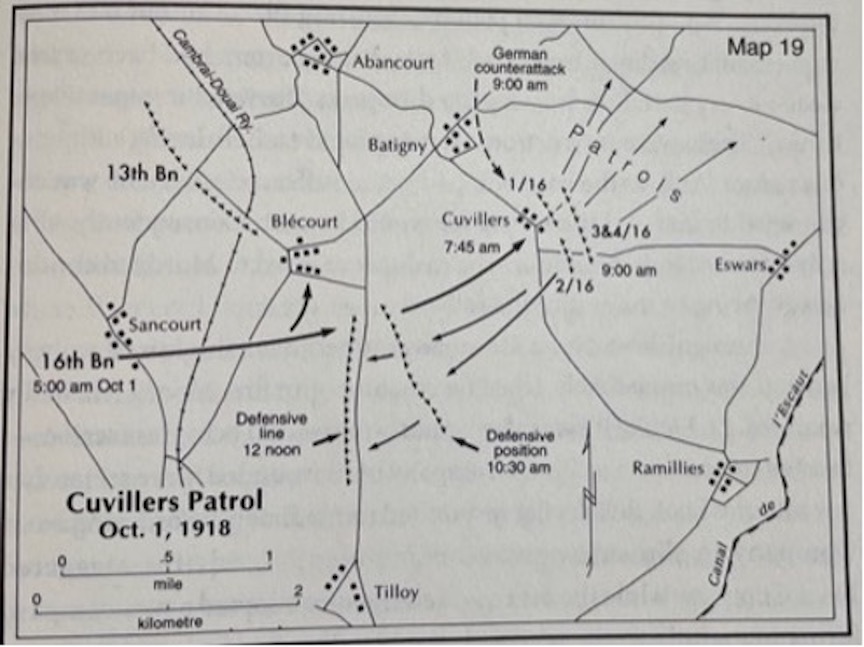

Sgt William Jackson and Cpl Alexander McMillan were the last two members of the Hamilton contingent to be wounded in action while serving with the 16th Bn. Both individuals were wounded and captured by the Germans on 1 October 1918 at the Battle of Canal Du Nord, during the advance toward Cuvillers. This was the last battle in which the 16th Bn fought. It was notable for the confused fighting at Cuvillers, an unexpectedly strong German counter-attack, and the death of Maj Bell-Irving, a Seaforth officer who, at the time, was the 16th Bn’s acting commanding officer. This battle cost the 16th Bn 345 casualties, including 69 prisoners of war – the battalion’s largest single loss of POWs during the entire war.

Image 13: Cuvillers Patrol. Sgt Jackson and Cpl McMillan were the last of the former 91st wounded in action and then captured at Cuvillers. Source: Brave Battalion by Mark Zuehlke, 2008

Image 13: Cuvillers Patrol. Sgt Jackson and Cpl McMillan were the last of the former 91st wounded in action and then captured at Cuvillers. Source: Brave Battalion by Mark Zuehlke, 2008

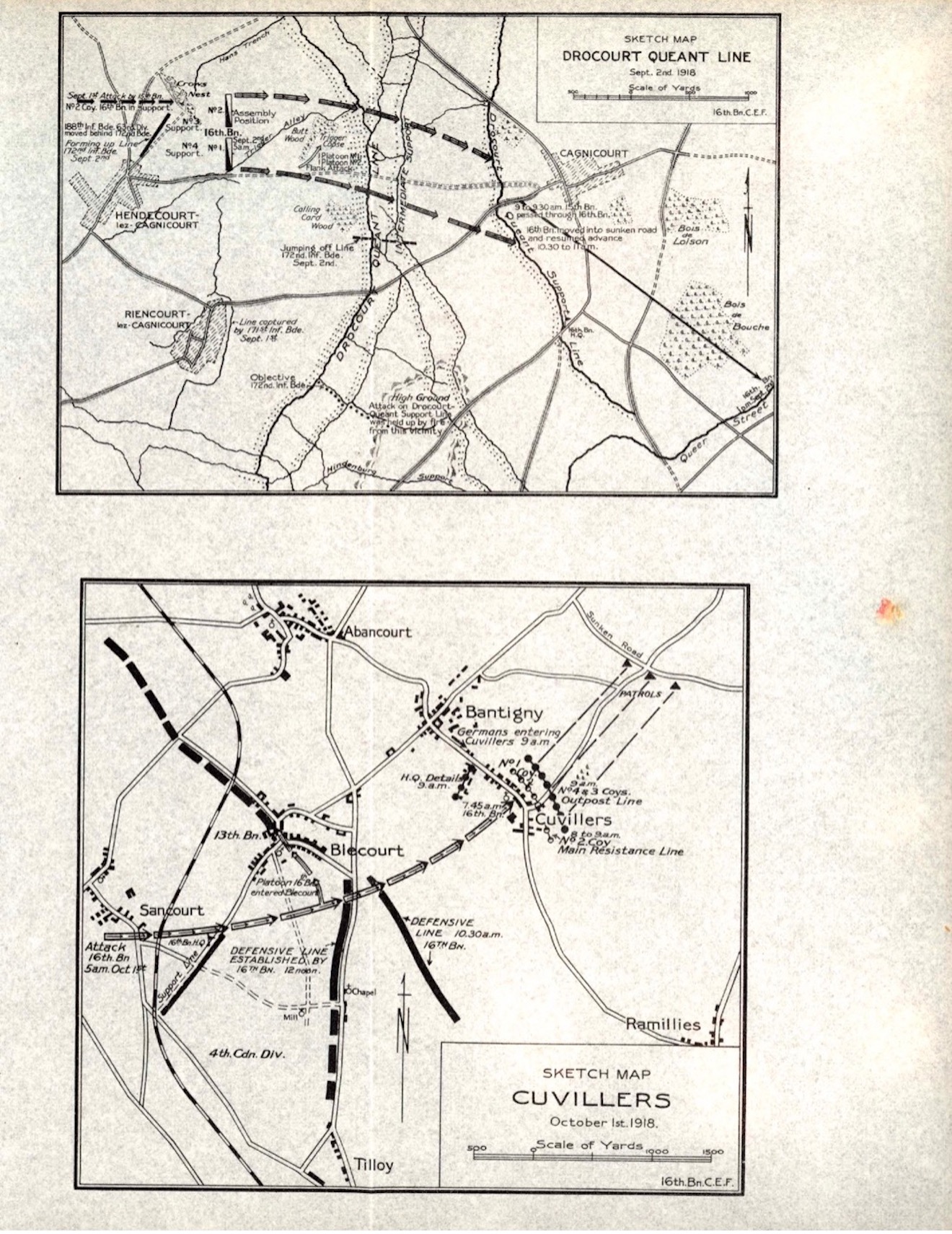

Image 14: D-Q Line and Cuvillers. Urquhart, Hugh. The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1932).

Image 14: D-Q Line and Cuvillers. Urquhart, Hugh. The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1932).

Sgt Jackson was born in England in September 1889. He had served in the 91st Regiment prior to enlisting in the 16th Bn at Valcartier in 1914. Before the war, he was single and worked in Hamilton as a liquor expert. He had received a GSW to the left leg in May 1915 at Festubert, and shrapnel wounds to the left eyebrow and thigh in September 1916 at the Somme. Unfortunately, the nature of his wound at Cuvillers is unknown as much of his CEF personnel file is illegible. He was held as a POW at Giessen, Germany, released on 5 December 1918, and posted to the No.1 Rest Camp, Dover. He survived the great influenza pandemic of 1918, returned to Canada and was discharged from the CEF on 25 March 1919.

Cpl McMillan was born in Scotland in July 1888 and had served with the Imperial 1st Bn, Cameron Highlanders before settling in the Hamilton area. He was single and worked as a farmer. He transferred to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade HQ on 2 November 1914, shortly after the 16 Bn had arrived in England. He served in France and Belgium between November 1915 and October 1918. At an unknown date, he returned to the 16th Bn. Unfortunately, much of his service record is illegible. On 1 October 1918, Cpl McMillan was reported wounded in action and taken prisoner. He had suffered a gunshot wound that fractured his right shoulder and was held as a POW at Parchim, in Mecklenburg, Germany. He was repatriated to England on 17 December 1918 for further medical treatment. While in hospital, he survived the great 1918 influenza pandemic. He was returned to Canada on 23 May 1919 and was demobilized from the CEF in December of that year. He died on 20 November 1965 at the age of 78.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF THE ORIGINAL 91st REGT OFFICERS AND SENIOR NCOs

Major Henry Lucas Roberts

Maj Roberts was born in Scotland in December 1877 and had served in the Territorial Force with the 4th King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the Royal Garrison Artillery, West of Scotland Artillery District. He later settled with his wife in the Hamilton area, where he took up fruit growing and obtained a commission in the 91st Regiment. In 1910 he passed the Militia Staff Course invigilated by Brigadier General W.D. Otter, CVO, CB.

In August 1914, Maj Roberts was 36 years old when he volunteered for service with the CEF. He was the officer in charge of the 91st Regiment’s contingent, which formed F Coy, 16th Bn at Camp Valcartier. He was quickly appointed Junior Major in Battalion HQ and sailed to England with the 16th Battalion on 3 October 1914. The 16th Bn’s war diary recorded that he was fully involved with unit training and administration.

However, Maj Roberts was not destined to serve with the CEF in France. In February 1915, he transferred to the British Army, rejoining the Royal Garrison Artillery. He served with heavy siege howitzer batteries in England, France, Salonika (Macedonian Front), and Mesopotamia (post-war Iraq). In August 1918, he relinquished his commission in the Royal Garrison Artillery and returned to Canada, where he was posted to the siege artillery section of the Royal Canadian Artillery’s regimental depot, No.2 Militia District, for the remainder of the war.

Maj Roberts suffered from a nervous disability caused by the strain of campaigning in Mesopotamia. He was demobilized in 1919 and returned to civilian life. He died in 1937 at the age of 59.

Captain (later Lieutenant Colonel) Frank Morison, DSO

Capt Morison was born in Toronto in June 1880. He was single and practised law in Hamilton. He obtained a commission in the 91st Regiment and had served for nine years prior to the war. He was 34 years old when he volunteered for service with the CEF in September 1914. At Camp Valcartier, he was appointed officer commanding F Coy, 16th Bn, and his signature appears on virtually all of the company’s attestation papers. However, when the 16th Bn was reorganized in England, F Coy was combined with a Seaforth Coy and restructured as No.3 Coy. Capt Cecil Merritt, a Seaforth offficer, was appointed officer commanding and Capt Morris was appointed second in command. Cecil Merritt was also the father of Charles Cecil Ingersoll Merritt, who would be awarded a Victoria Cross at Dieppe during the Second World War.

Capt Morison was present at the Second Battle of Ypres and participated in the attack and close quarter bayonet fighting during the evening of 22 April 1915. During the early morning of 23 April 1915, he was ordered to reorganize No.3 Coy, gather stragglers, and dig in a defensive position behind Kitchener’s Wood. During this action, Capt Cecil Merritt was fatally wounded and Capt Morison was appointed officer commanding No.3 Coy.

Capt Morison gained a reputation as an efficient officer who led from the front. On 20 May 1915, during the Battle of Festubert, he advanced his company some 1,400 metres from the start line, across shell-pitted fields bisected by deep drainage ditches and abandoned breastworks, to the objective – a feature that became known as Canadian Orchard. He led a daring assault through a ditch surmounted with a hedgerow that had two gaps in it, which caught the German defenders off-guard.

Number 3 Company, on striking the road west of the Orchard, found themselves faced with a ditch on the father side of which stood a thick hedge, in which only two small openings could be seen. Towards one of these Captain Morison started to make a run, but was pulled back by bomber Appleby, who said “bombers go in front of officers here, sir,” and leaving his officer to take second place, jumped the ditch and pushed through the gap, quickly followed by the company, which in [single] file, making use of the two openings, rushed its objective (Urquhart, p. 80).

The capture of this feature was notable because it was the deepest penetration of German defences by any unit in the British First Army during the Battle of Festubert.

For his leadership at Canadian Orchard, Capt Morison was promoted to major and awarded the DSO, one of eight awarded to the 16th Bn. His citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and ability on 20 May 1915 when he commanded the leading company in the attack on the orchard at La Quinque Rue. Captain Morison captured the enemy’s position, which was of primary importance, under heavy shrapnel, rifle and machine gun fire.” London Gazette No. 29275, 25 August 1915. He was also Mentioned in Dispatches, London Gazette, 30 November 1915.

Due to appalling weather and unsanitary field conditions, Maj Morison suffered from chronic sinus problems and a bacterial infection called trench mouth. In November 1915, he was evacuated to England on sick leave and had his sinuses operated on and tonsils removed. A medical board deemed him unfit for active service. In January 1916, he was struck off strength from the 16th Bn. In between hospital stays in England, he worked as a compensation officer.

Maj Morison returned to Canada in November 1916 until late February 1917. He returned to England in 1917 and served in a number of staff positions with the Ministry of Overseas Military Forces of Canada, in London. In 1918 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and served as assistant military secretary to Lt Gen Sir Richard Turner, VC, Chief of General Staff, OMFOC. Lt Col Morison was demobilized in May 1920.

On 18 February 1920, while still in London, Lt Col Morison married Nora Angela Bell-Irving (née Benwell), the young widow of Maj Roderick Bell-Irving, DSO, MC. Nora Benwell was born in Vancouver in September 1893 into an upper-middle-class family. Her father was a businessman who ran his own investment company. The Morison wedding took place in St Marylebone Westminster Parish Church, and the couple honeymooned in Eastbourne. He was 39 and Nora was 26. It is possible that Nora Bell-Irving had been in England doing voluntary work in support of the war effort.

Maj Bell-Irving was killed in action on 1 October 1918 during the Battle of Canal du Nord while temporarily commanding the 16th Bn. A Seaforth officer, he joined the 16th Bn at Valcartier and had originally served as a platoon commander in F Coy under the command of then Capt Morison. Roderick Bell-Irving came from a very prominent Scottish family in Vancouver. He and his five brothers all saw active service during the First World War.

Lt Col Morison and his new wife returned to Hamilton after the war, where he resumed his law career, being appointed King’s Counsel (KC) for his contribution to the legal profession. They had two children. Frank Morison died in 1962 at the age of 83. Nora Morison died in 1965 at the age of 72.

Lieutenant Henry Duncan

Lt Duncan was born in Seattle, Washington, in September 1892. His family emigrated to Canada and settled in Sudbury, Ontario. Lt Duncan was single and employed as a bank clerk prior to the war. He was 21 years old when he volunteered for service with the CEF in September 1914. He had no prior military experience but was appointed Platoon Commander of 12 Platoon, F Coy at Valcartier. This company was later reorganized in England as No.3 Company.

Lt Duncan sailed to England with the 16th Bn and landed in France with the unit on 9 February 1915. He saw action at the Second Battle of Ypres and at the Battle of Festubert. His gallantry was noted during the 20 May 1915 assault on Canadian Orchard under the command of Capt Morison. The 16th Bn’s Commanding Officer forwarded “recommendations of distinction” for both officers to 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade HQ. However, for unknown reasons, the chain of command did not endorse a gallantry award for Lt Duncan, one of countless soldiers who never received official recognition for their heroism and devotion to duty.

The rigours of front-line service took their toll on Lt Duncan’s health. In June 1915, he became sick with measles. He was evacuated to England, where he spent much of the next 15 months in and out of hospital with thyroid problems and severe influenza. He served in reserve battalions in England while recuperating.

In early September 1916, the 1st Canadian Division was moved to the Somme battlefield. On 20 September 1916, Lt Duncan rejoined the depleted 16th Battalion near Albert, where it was reorganizing following the recent fighting at Moquet Farm near Pozieres. The unit war diary noted disconcertingly that on that same day a 12-inch gun had been positioned some 50 metres from Bn HQ. The 16th Bn would soon be engaged, in a supporting role, in the attack on the German positions near Courcelette, known as the Battle of Theipval Ridge (Kenora Trench). Lt Duncan was given command of No.2 Coy with two attached platoons from No.4 Coy. These six platoons were tasked with following the main assault of the 14th and 15th Battalions, three to each battalion, to “mop up” any bypassed enemy troops. The remainder of the 16th Bn remained in the trenches but later supplied stretcher parties and also sent two companies forward to reinforce the depleted 14th Bn companies holding Kenora Trench.

At 20:00 hours on the night of 25 September 1916, Lt Duncan’s No.2 Coy departed from their assembly area and started to march five kilometres to their jumping-off trenches west of Courcelette for the next day’s attack. The platoons from No.4 Coy arrived without incident. However, the guide for No.2 Coy became lost and they stumbled around the battlefield in the dark for several hours. They entered the ruins of Courcelette and narrowly missed being shelled by a battery of German 5.9-inch field guns. About an hour before dawn, they fortuitously entered an abandoned German sap trench in no man’s land, which led towards the 14th Bn lines, and miraculously arrived at their shallow and crowded assembly trench, where they hunkered down to await zero hour.

Zero hour was set for 12:35 on 26 September 1916. The 14th Bn’s unit war diary records that the attack was organized in four waves along a single company frontage. The first wave left the jumping-off trenches, followed at intervals of 70 to 100 yards by the second wave, three platoons of Lt Duncan’s mopping-up party, and the third and fourth waves. The 14th Bn companies quickly reached their first objective, Sudbury Trench, some 400 metres from the start line (see image 9). This was a small detached work approximately 250 metres long whose west flank abutted a cut along the Grandcourt Road. The first wave and mopping-up party consolidated on this objective while the other waves advanced towards the second objective at Kenora Trench, slightly east of the junction with Regina Trench. At 12:40, 45 German POWs were sent to the rear from the area of Sudbury Trench. However, Lt Duncan’s platoons encountered some 50 Germans in the trench and in dugouts along the sunken road; they refused to surrender and fought to the last man, even though surrounded. The dugouts, opening onto the sunken road, were cleared with white phosphorus bombs. Lt Duncan and No.2 Coy remained in position at the trench and dugouts until relieved the next day.

On 8 October 1916, the 16th Bn participated in the Battle of Ancre Heights (Regina Trench). Lt Duncan was again in command of No.2 Coy, in the absence of Maj Bell-Irving, who was attending a Senior Officers’ School in England. The assault was launched on a two-company frontage with two companies following in the second wave. No.2 Coy was situated on the right side of the second wave.

From their very inception, misfortune dogs the steps of certain enterprises and here we seem to be dealing with an undertaking of that nature. The original date of the operation was postponed, the plan of attack altered, and up to the last moment it seemed impossible, as a large section of Regina Trench was on a reverse slope, to get accurate reports regarding the wire. The artillery observers said it was cut, the infantry said it was not. As far as the 16th Bn was concerned, its scouts had no opportunity to reconnoitre the ground (Urquhart, p. 180).

It might be added that aerial observation over Regina Trench was not possible either, due to overcast skies and heavy rain.

The left two companies got held up in front of uncut wire in front of Regina Trench until famously rallied by Piper Richardson, posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for playing his pipes along the wire. The right two companies had an easier time assaulting Regina Trench through partially cut wire. Nonetheless, 16th Bn’s casualties were horrendous. The entire battalion had an effective strength of 98 all ranks to hold some 300 metres of trench. In the face of repeated German counter-attacks and isolated from resupply, the 16th Bn exhausted its ammunition. By 18:00 that afternoon, the remnants of the 16th Bn retired to their start line, having suffered 344 casualties, including eight officers killed or fatally wounded. Lt Duncan was one of them. He was listed as missing in action and presumed dead. His body was never recovered. His name is inscribed on the Vimy Memorial in France.

Lieutenant (later Captain) Paul Powis

Lt Powis was born in Hamilton, Ontario, in November 1886. Prior to the war, he was single and employed as a fire insurance broker. He had previous service with 2nd Dragoons, an Ontario NPAM cavalry regiment. He was 28 years old when he volunteered to join the CEF in September 1914. At Valcartier, he was designated a supernumerary officer and assigned to the 16th Bn’s Base Coy.

Lt Powis sailed to England with the 16th Bn but initially remained in England with Base Coy in an administrative role. Following the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of Festubert, he joined the 16th Battalion in France on 28 May 1915 with a number of other reinforcements. In early June 1916, he was promoted to captain and seconded to the 3rd Canadian Trench Mortar Battery. Later designated the No.3 Canadian Light Trench Mortar Battery, it was formed of personnel from 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade and equipped with 3-inch Stokes mortars.

On 7 August 1916, while serving in the Ypres Salient, two days prior to the 16th Bn’s withdrawal from the Salient, Lt Powis received a severe leg wound, possibly from German counter-battery fire on his mortar position. A shell fragment was surgically removed the next day, but the wound became septic. Lt Powis was evacuated to England, where he spent two months in hospital. His wound healed but left a 23-centimetre scar. On 30 November 1916, he was struck off strength from the 16th Bn and returned to Canada for further medical treatment. He was deemed medically unfit for active service and spent the remainder of the war serving with the Military Hospital Commission Council (MHCC), No.3 Militia District Depot. He was demobilized in 1919 and returned to civilian life. He died in 1933 at the age of 47.

Lieutenant Alexander Colquhoun

Lt Colquhoun was born in Hamilton, Ontario, in December 1894. Prior to the war, he was single and employed as a clerk and surveyor. Colquhoun had previous but unspecified service with the 91st Regiment. He was 21 years old when he volunteered to join the CEF in September of 1914. At Valcartier, Colquhoun was designated a supernumerary officer and assigned to the 16th Bn’s Base Coy.

Lieutenant Colquhoun sailed to England with the 16th Battalion but initially remained in England with Base Coy in an administrative role. He joined the 16th Battalion in France on 26 April 1915. Colquhoun was present at the Second Battle of Ypres, where he suffered minor lung damage from poison gas leaving him short of breath. He was also present at the Battle of Festubert. At the end of September 1915, he was evacuated to England to have a tumour removed.

In December 1915, he transferred to the Royal Naval Air Service for pilot training. On 25 May 1916, Colquhoun survived an airplane crash that left him with general nervous exhaustion. The next month he was struck off strength from the RNAS and returned to Canada. He experienced difficulty walking and was deemed medically unfit for active service. Colquhoun spent the remainder of the war serving with the Military Hospital Commission Council (MHCC), No.2 Militia District Depot. He was demobilized in 1919.

Colour Sergeant George Mitchell

C/Sgt Mitchell was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, in June 1881. He served for 12 years with the Imperial Black Watch Regiment. After immigrating to Canada, he settled in Hamilton and found employment as a drop forge operator. In 1908 he joined the 91st Regiment and served for six years. He was married and 33 years old when he volunteered to join the CEF in September 1914. At Valcartier, he was assigned to F Coy, later reorganized as No.3 Coy in England.

C/Sgt Mitchell sailed to England with the 16th Bn, where he reverted to the rank of Sgt and was appointed platoon Sgt. Due to the harsh winter and poor quarters, Sgt Mitchell became sick with pleurisy, an inflammation of the lung caused by influenza or pneumonia. However, he was released from hospital in time to land in France with the 16th Bn on 9 February 1915. He was present during the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of Festubert. The 16th Battalion suffered 277 casualties, including 71 fatalities at Festubert, and Sergeant Mitchell was one of them. Sometime between 18 and 22 May 1915, he was killed in action during an attack northeast of Festubert when hit in the head by an enemy rifle bullet. As there is no record of his burial, his body was likely never recovered. His name is inscribed on the Vimy Memorial in France.

Sergeant (later WO 2 CSM) John Stewart

Sgt Stewart was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, in March 1886. He served with the 1st Bn, Imperial Gordon Highlanders. After emigrating to Canada, he settled in Hamilton, where he worked as an electrician. Stewart served with the 91st Regiment for an unspecified period of time. He was married and 28 years old when he volunteered to join the CEF in September of 1914.

Sgt Stewart sailed to England with the 16th Battalion and landed in France with the unit on 9 February 1915. He was present during the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of Festubert. Sgt Stewart was promoted to warrant officer and on 10 August 1915 appointed CSM. However, he became sick with rheumatoid fever and on 24 September 1915 was evacuated to hospital in England. He experienced chronic arthritic pain in his feet and knees, which rendered him unfit for active service. He served with various CEF reserve battalions in England until 25 October 1917, when he was returned to Canada. A medical board deemed him unfit for further service and he was discharged on 22 January 1918. He returned to civilian life and died in 1931 at the age of 35.

Sergeant George Slessor

Sgt Slessor was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, in July 1872. After emigrating to Canada, he settled in the Hamilton area, where he plied his trade as a mason. In 1907 he joined the 91st Regiment and served for seven years. George Slessor was married and 42 years old when he volunteered to join the CEF in September 1914. One of the oldest of the 91st Regiment’s contingent, he was one of eight individuals who were over the age of 40, including three who were aged 43. At Valcartier, he was assigned to F Coy, later reorganized as No.3 Coy in England.

Sgt Slessor sailed to England with the 16th Battalion and landed in France with the unit on 9 February 1915. For reasons unknown, he reverted to the substantive rank of corporal while serving as lance sergeant with all the duties and responsibilities of a sergeant while earning a corporal’s lesser pay.

On 3 March 1915, the 1st Canadian Division assumed responsibility for holding a six-kilometre section of the front at Fleurbaix, relieving the 7th British Division in preparation for the Neuve Chapelle offensive. Although not directly involved in the three-day battle, this period was nonetheless a baptism of fire for the 1st Canadian Division and the CEF official history notes that the division lost 100 casualties while holding the trenches in support. The 16th Battalion suffered eight killed in action/died of wounds and ten wounded in action during March 1915.

Sgt Slessor was one of the wounded. On or about 15 March 1915 at Fleurbaix, he received a gunshot wound that caused three different wounds in a row across his back but did not puncture his lungs. His wounds became septic and he was evacuated to hospital in England. He was returned to Canada later in 1915 for a period of convalescence.

Sgt Slessor rejoined the 16th Bn in France on 28 August 1916, shortly after the 1st Canadian Division had withdrawn from the Ypres Salient and moved south towards the Somme battlefield. He was posted to 11 Platoon of No.3 Coy. During the evening of 27 September 1916, No.3 Coy was ordered into Kenora Trench to reinforce the badly depleted 14th Bn, which had earlier captured a section of the trench. However, their guide became disoriented in the dark and No.11 and 12 Platoons were fired upon when they unwittingly approached a German position, Fortunately the two platoons were able to withdraw with few casualties. During this action, Sgt Slessor became separated from his platoon and was feared missing in action. He eventually made his way to an unoccupied section of Kenora Trench and was found the next morning, sound asleep, with his head resting on a dead German.

The 16th Bn had suffered heavy casualties during the Kenora Trench fighting and did not expect to go back into action at the Somme. However, on 7 October 1916 the 16th Bn assembled north of Courcelette and prepared to attack Regina Trench early the next morning. Zero hour was set at 04:50 hours. Regina Trench was located on a reverse slope some 650 metres behind Kenora Trench. It was well revetted and protected by a thick belt of wire some ten feet deep, largely untouched by artillery fire. Despite being held up on the wire entanglements and suffering heavy casualties in hand-to-hand fighting, the 16th Bn evicted the German defenders from a section of Regina Trench and held a frontage of some 330 metres. Heavily depleted by casualties, only 98 all ranks, including four officers and five senior NCOs, remained to defend the trench from incessant German counter-attacks. The left flank of the trench was unsecured and an improvised barricade of sand bags and wood was hastily constructed to block German troops from attacking along the trench. Sgt Slessor was posted at the block with a Lewis gun and a handful of troops. On 8 October 1916, shortly before 06:00, the Germans launched a concerted bomb (grenade) attack at the block and overran the post. Heavy hand-to-hand combat drove the Germans back.

During this action, Sgt Slessor received a gunshot wound to the right thigh and was reported missing in action. He was later reported being held at Hermies, Germany, as a POW. On 18 October 1916, he died of his wound. He was 30 years old. His German captors buried his remains at the Notre Dame Cemetery in Cambrai. These were subsequently moved to the Porte-de-Paris Commonwealth Cemetery near Cambrai.

Image 15: Headstone of Sgt George Slessor, buried in Porte-de-Paris Commonwealth Cemetery near Cambrai. Source: www.findagrave.com.

Image 15: Headstone of Sgt George Slessor, buried in Porte-de-Paris Commonwealth Cemetery near Cambrai. Source: www.findagrave.com.

Sergeant John Cochran

Sgt Cochran was born in Bruce County, Ontario, in August 1880. He lived in Hamilton, where he worked as a butcher. Prior to the war, he had 12 years of service with the 91st Regiment. He was single and 34 years old when he volunteered to join the CEF in September 1914.

Sgt Cochran sailed with the 16th Bn to England and landed in France with the unit on 9 February 1915. He was with the 16th Battalion during the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of Festubert. On 20 May 1915, during the Battle of Festubert, he was an acting platoon commander of the left platoon of No.3 Coy, which became disoriented upon leaving the trenches during the advance on the objective known as Canadian Orchard.

The men of that unit made a half left turn and advanced toward the front of the Coldstream Guards. The Guards shouted at them and pointed out the orchard, whereupon Sgt Cochrane [sic], the platoon Sgt, turned his men about and led them towards that spot, correcting the dressing of the ranks as he went along. Cochrane, during the advance, was hit in five places, never-the-less he remained with his command until the objective was reached. Afterwards, while being carried to the dressing station, he slid off the stretcher and insisted on being allowed to report to Capt Rae to give that officer details of the situation. When he reached Rae’s headquarters, the pain was so intense that he was forced to double up on his hands and knees, the only posture in which he could get relief from his agony, and from that position he made his statement (Urquhart, p. 80).

Sgt Cochran’s medical records state that a shrapnel shell had exploded near him, injuring his left buttock, hips, right thigh, and right foot. He was evacuated to hospital in England, where he remained until December 1915. A medical board determined that he had numerous scars and extensive lacerations of the muscles in his right thigh, which interfered markedly with walking. He also had two toes from his right foot amputated.

Sgt Cochran was subsequently posted to a number of CEF reserve battalions in England and was transferred to the Canadian Army Service Corps (CASC). In April 1916 he was hospitalized with influenza, and in July 1916 he returned to hospital with second-degree burns to his face and left hand. While in a butcher shop, hot grease was splashed onto him when someone had attempted to put out a grease fire with water. He was released from hospital in October 1916 and repatriated to Canada for further convalescence. Deemed fit for permanent light duty, he was taken on strength with the 3rd Pioneer Battalion, later reorganized as the 11th Battalion, Canadian Railway Troops (CRT). He served with the CRT in France between May 1917 and February 1918. He was then posted to the CRT regimental depot at Purfleet, Essex, England, for the remainder of the war.

Sgt Cochran returned to Canada on 14 December 1918. He was discharged from the CEF on 12 January 1919. A medical board determined that he had considerable mental disturbance and hesitancy in speech and was startled by sudden noises. He returned to civilian life and died in 1954 at the age of 74.

Sergeant John Steele

Sgt Steele was borne in Perthsire, Scotland, in June 1887. After immigrating to Canada, he settled in the Hamilton area, where he worked as a carpenter. He had served in the 91st Regiment prior to the war. He was single and 27 years old when he volunteered to join the CEF in September 1914. At Valcartier, he was assigned to F Coy, later reorganized as No.3 Coy in England.

Sgt Steele sailed with the 16th Battalion to England and landed in France with the unit on 9 February 1915. He was with the 16th Battalion during the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of Festubert. On 21 May 1915, he was reported killed in action. The circumstances and exact date of death are unknown. It is possible that he died during the attack at Canadian Orchard, where the 16th Bn suffered 71 all ranks killed in action. His remains were buried in Essex Farm Commonwealth Cemetery northwest of Ypres. He was 27 years old. It was in Essex Farm Cemetery that Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae of the Canadian Army Medical Corps wrote the poem “In Flanders Fields” in May 1915.

SOURCES

Nicholson, G.L.W. Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919: The Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War (Queen’s Printer, Ottawa, 1964).

Urquhart, Hugh. The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1932).

Williams, Casey, et al. 100 Years of Valour; A Centennial Celebration of the Canadian Scottish Regiment (Princess Mary’s) (Paradigm Publishing, 2012).

Zuehlke, Mark. Brave Battalion: The Remarkable Saga of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish) in the First World War (Mississauga: John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008).

https://library-archives.canada.ca digitized CEF records:

Personnel Records of the First World War

CEF Files (Attestation papers and service files)

Unit War Diaries – 14th, 15th, and 16th Infantry Battalions

CEF 16th Bn 1915 Nominal Roll

Circumstances of Death Registry

Commonwealth War Graves Registry

Veterans Death Cards

https://militaryandfamilyhistoryblog Steve Clifford’s genealogy and military history website which includes references to the 16th Bn. Accessed numerous times in 2023.

https://www.WikiTree.com Biographical information on the Bell-Irving, Benwell, and Morison families.

FOREWORD

The 91st Canadian Highlanders contributed troops to the first draft of soldiers to be sent to the UK and eventually France in 1914–1915. While this fact is readily known in the early histories of the Argylls, very little detail about what happened to the Hamilton contingent has been assembled until now. With the very kind assistance of David G. Morgan, we now have a narrative specifically relating to the contingent that was sent to the 16th Battalion CEF in 1914. The 16th Bn suffered heavy casualties throughout the war, and the soldiers from the 91st Canadian Highlanders were not spared; by 1916 the full majority of their ranks were killed in action, wounded, missing, or prisoners of war. David Morgan has assembled the stories of the Hamilton contingent with emphasis on the officers and senior NCOs. David Morgan is a former Canadian Scottish Regiment officer and a friend of the Argyll Museum and Archives. — LCol (ret) Tom Compton, CD, BA, Director, Argyll Regimental Museum & Archives

Images 2 and 3 (above and below): 91st Highlanders arrive by train at Niagara-on-the-Lake, likely pre-war. Argyll Museum and Archives.

Images 2 and 3 (above and below): 91st Highlanders arrive by train at Niagara-on-the-Lake, likely pre-war. Argyll Museum and Archives.

ROLL OF HONOUR

The following members of the Hamilton contingent were killed in action or died of wounds.

Fleurbaix Area – Trenches at Festubert

Pte Stephen Richie KIA 14 March 1915

Pte James Russell KIA 18 March 1915

Pte John Turmbull KIA 19 March 1915

Second Battle of Ypres – German Gas Attack and Counter-Attack at Kitchener’s Wood

Cpl Frederick Bryant KIA 22 April 1915

Pte James Adamson KIA 23 April 1915

Pte Peter Carroll KIA 23 April 1915

Pte Robert Dean KIA 23 April 1915

Pte James Duffy KIA 23 April 1915

Pte Hugh Dunbar KIA 23 April 1915

Pte Gilbert Howe KIA 23 April 1915

Pte Alexander McFarlane KIA 23 April 1915

Battle of Festubert – Attack at Canadian Orchard

Pte Robert Wilson KIA 20 May 1915

Sgt John Steele KIA 21 May 1915

Pte Frederick Flook. WIA 22 May 1915, DOW 6 August 1915

Pte Harry Black KIA between 8/22 May 1915

L/Cpl Frederick Bleakley KIA between 18/22 May 1915

Pte Nicol Findlater KIA between 18/22 May 1915

Pte Alexander McIntyre KIA between 18/22 May 1915

Sgt George Mitchell MIA presumed KIA between 18/22 May 1915

Piper Angus Morrison KIA between 18/22 May 1915

Ypres Salient – Trenches 45/51 North of Hill 60 by Mt Sorrell

Pte Hugh Aitken KIA 01 April 1916

Ypres Salient – Trenches Hill 60 Sector

Pte William Trezise KIA 18 July 1916

Somme – Battle of Thiepval Ridge (Kenora Trench)

L/Cpl Donald Campbell KIA between 25/28 September 1916

Somme – Battle of Ancre Heights (Regina Trench)

CQMS James Boyes KIA 08 October 1916

Lt Henry Duncan MIA presumed KIA 09 October 1916

Sgt George Slessor. MIA between 08/09 October 1916, POW, DOW 18 October 1916

Telegraph Hill Sector – Tilloy Raid

Sgt James Gemmell KIA 28 July 1918

Battle of Amiens

L/Cpl John Hall KIA 11 August 1918

HONOURS AND AWARDS

Distinguished Service Cross (DSO)

Lt Col Frank Morison: DSO, Medaille d’Honneur avec Glaives en Vermeil (France), MID, LG 25 August 1915

Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM)

Sgt George Urie: DCM, LG 03 June 1919

Military Medal (MM)

Sgt Walter Vyse: MM and Bar, MID LG 19 November 1917

CSM John Newton: MM and Bar, MID 27 March 1919

CQMS James Boyes: MM, LG 03 Jun 1916

Cpl Edward Gallagher: MM, LG 19 November 1917

CSM Ernest Picton: MM, LG 21 December 1916

Sgt Robert Stewart: MM, LG 09 July 1917

Meritorious Service Medal (MSM)

CQMS William Stokes: MSM, Croix de Guerre (Belgium), LG 03 June 1919

Mentioned in Dispatches (MID)

Lt John Bizley MID: LG 22 June 1915

Cpl Charles Payne: MID, LG 31 December 1915

Pte Ernest Appleton: MID, LG 01 January 1916