Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

I took notice of Pte James Bannatyne many decades ago, an acquaintance made courtesy of CSM George Mitchell’s terse diary entry for 2 August 1944. For this year’s Argyll month of remembrance, I decided to do a biography of young James. His personnel file quickly revealed that he was Ojibwe and had been at a residential school for a long time. My quest to find out more about him has taken many paths; most were dead ends, and I have many folks representing a number of institutions to thank. First, I am grateful to Chief Clifford Bull of the Lac Seul First Nation for his cooperation, his support, and that of his community. He provided critical contact with Cecile Bannatyne, Dolores Bannatyne, Jessie Bull, and Elder Evelyn Makahnouk (née Sapay; sister of Gerald Bannatyne’s wife, Christine Sapay). I thank all of them for frank interviews and considerable assistance.

There are numerous archivists, educators, and librarians to thank: Kim Arnold, Archivist/Records Administrator, Presbyterian Church in Canada Archives; Susan Carey, Ear Falls Public Library; Shane Bannatyne (a distant relation), Winnipeg; Wendy MacDonald, Sioux Lake Public Library; Terri Finney, Sioux Library; Dr Braden Te Hiwi; Karen Ashbury, Reference & Access Archives Assistant, National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), University of Manitoba; Bethany Waite, Museum and Heritage Coordinator, Dryden & District Museum; Braden Murray, Educator, THE MUSE | Lake of the Woods Museum; Mike Starratt (Lac Seul Floating Lodges); and Lori Jackson, Library Assistant, Reference Department/Accounts, Kenora Public Library. The online records of the NCTR, the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre at Algoma University, and the Anglican Church of Canada are invaluable for anyone researching a residential school or an individual who attended one. I am hopeful that a third-party request for information at the NCTR will yield more information on James Bannatyne. If it does, this biography will be revised accordingly.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte James Bannatyne (1926-44) (H 103880)

KIA 2 Aug 1944

It is a long way from the lands of the Lac Seul First Nation in northwestern Ontario to the battlefields of France. It is a longer way from the world of the Lac Seul First Nation in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s to the battlefields of France in 1917–18 and 1944. Yet, two generations of the Bannatyne family made the journey across continents and cultures; one did not return. Their lives mark a historical passage from the world of the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) people who dwelt and still remain in the Lac Seul area. The displacement of their traditional life began with French and British fur traders in the 17th century. It accelerated with the westward move of population in the 19th century, and overtook the area in the 20th century. The discovery of gold in Red Lake in 1925 came, as historian John Richthammer writes, “at a cataclysmically high cost to the district’s original settlers.” Mining, railways, roads, and dams played their part, and were abetted by compulsory education at residential schools.

The years following confederation brought significant changes to the indigenous people living in what is now the northwest portion of Ontario (north and west of present-day Thunder Bay to Winnipeg). The new federal government wasted little time in purchasing Rupert’s Land in 1868, the first formal act of Canadian expansion to the west. Europeans had been pushing westward since the 17th century and the settlement at Red River had its roots in the early 19th (see From the Red River settlement to Manitoba, 1812-70) . The Red River rebellion (1869–70) and the subsequent establishment of Manitoba (1870) had further ramifications. The federal government’s military expedition to Red River necessitated travel through Anihšināpē, or Anishinaabe, lands. The federal government commenced negotiations with them in 1870 and signed Treaty No. 3 in 1873. The planned route for the promised Canadian Pacific Railway made it essential from the government’s perspective.

Map showing Lac Seul.

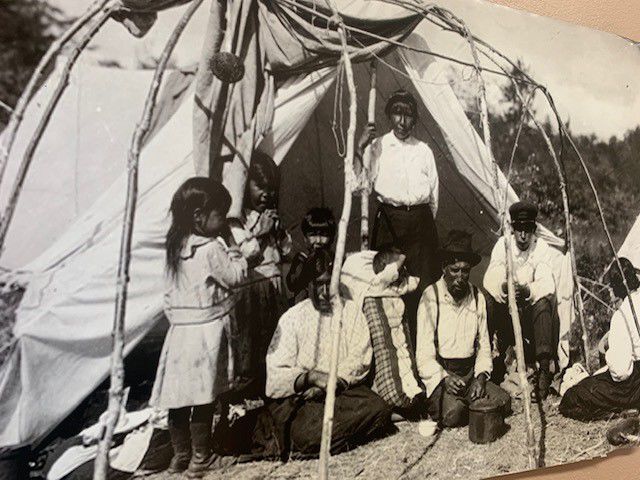

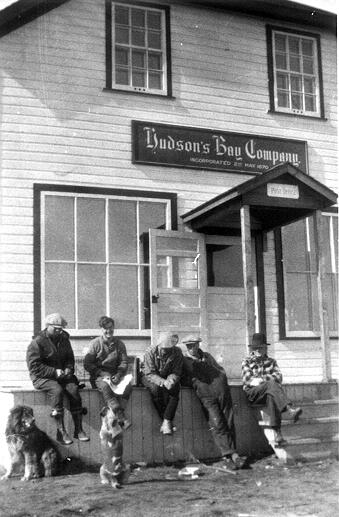

Three of four of James Bannatyne’s grandparents were Anishinaabe or Ojibwe, born in the Lac Seul area of the Kenora District in the 1870s; both maternal grandparents were born there in the 1870s as was his paternal grandmother, Margaret Wahweya Round (1876–1910). His paternal grandfather, Andrew Robert James Bannatyne (1856–1900) was born in Fort Garry and his paternal great-grandfather was born in 1829 on South Ronaldsay in the Orkney Islands, off the northwest coast of Scotland. The Hudson’s Bay Company recruited extensively in the Orkneys over the course of the late 18th and 19th century for service in the British North American fur trade, and the Bannatyne name in Lac Seul had its origins there. The present-day Lac Seul First Nation (Obishikokaag) is the oldest indigenous reserve in the Sioux Lookout District and is composed of communities on Lac Seul at Kejick Bay, White Fish Bay, and Frenchman’s Head. Gerald Vincent Bannatyne (1899–1989) was born in Lac Seul. His father died the following year in Winnipeg, and Gerald was living in Lac Seul with his mother, who died there in 1906. The small Anishinaabe communities gathered together in the summers before moving to winter camps, a pattern of life still in evidence in the 1920s. Gerald grew up in the area of Frenchman’s Head.

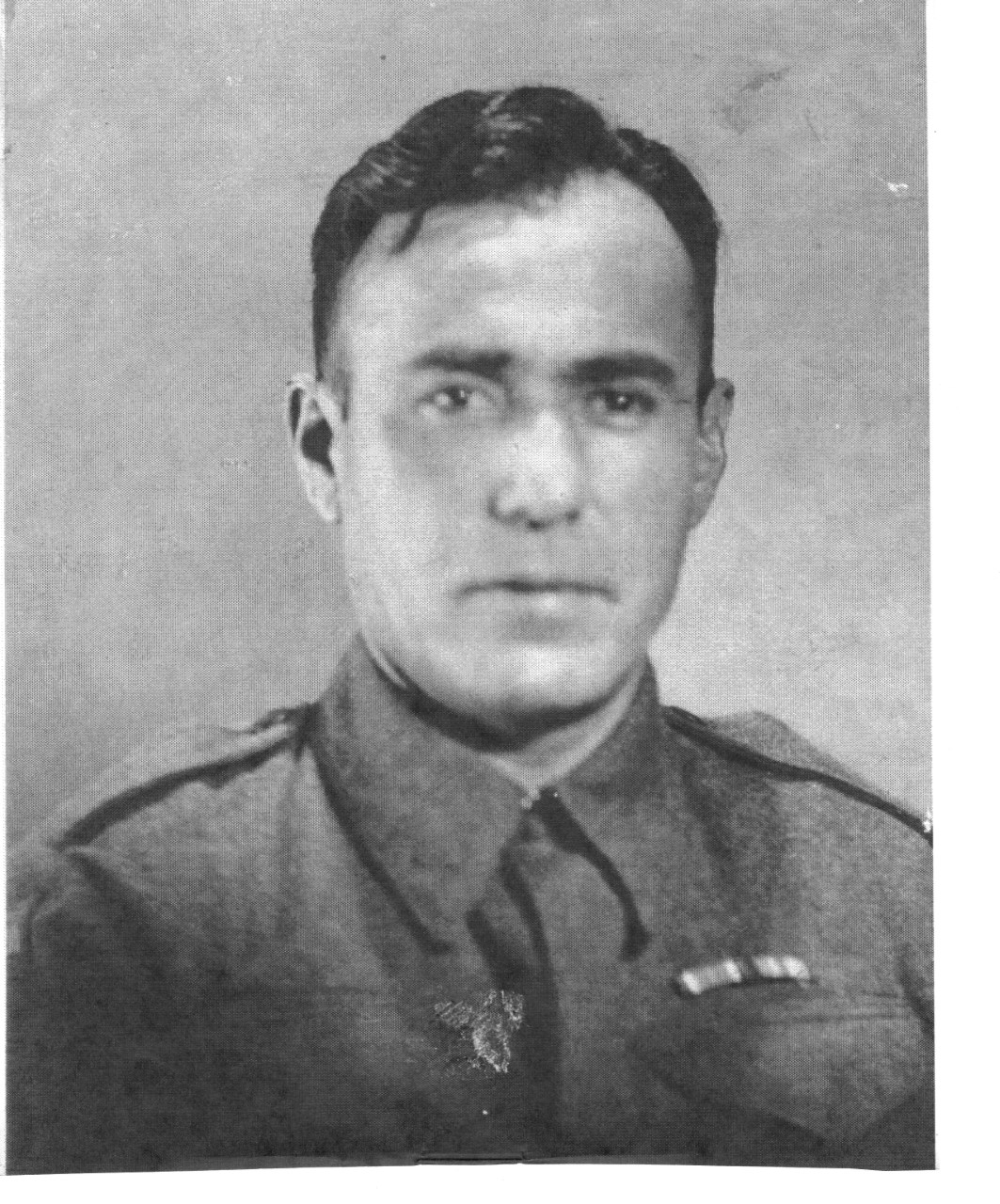

“Canadian Indian”

Little is known of Gerald’s life between 1906 and 1917. He grew up in the Ojibwe world of Lac Seul and he spoke the language fluently. Despite Lac Seul’s remoteness, it was touched by the First World War. Young Gerald Bannatyne lived in Lac Seul in 1917. He enlisted in Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) on 28 February 1917 in the 141st Overseas Battalion; he gave his birth date as 1896, presumably to ensure acceptance (in 1942, his future son would make a similar ploy to assure overseas service). Gerald was 5’, 9”, 148 lbs (up to 160 in 1918) with “Dark” complexion, brown eyes, and black hair. He was a “Laborer” (his medical case sheet has “Railwayman”) and gave his religion as Presbyterian (his marriage certificate of 23 November 1920 gives “Anglican”). Both parents were dead; he listed his brother, Charles Edward Bannatyne (1895–1973), as his next of kin; Charles’s address was Lac Seul. Gerald’s army file demonstrates that he could write English and, apparently, had acquired the language. Overseas, the 141st was broken up for reinforcement of other battalions; Pte Bannatyne went to the 52nd, another battalion from northern Ontario. He suffered “a slight shrapnel wound (middle left thigh posteriorly)” at Amiens on 8 August 1918 (the beginning of the 100 days). Wounded “about 3 a.m.,” Gerald’s injury was “Dressed by a stretcher-bearer,” whereupon Pte Bannatyne “walked” to the First Canadian Field Ambulance. Hospitalized in France for three days, he made a “good recovery – no disability results” in England over one and a half months. His medical case sheet describes him as “Canadian Indian.” Pte Bannatyne received his discharge at Winnipeg on 29 January 1919. His immediate post-war addresses were off the reserve yet still in the Lac Seul area: Webster, a railway point on Webster Bay on Lost Lake on the English River, and Millidge, another CNR railway point.

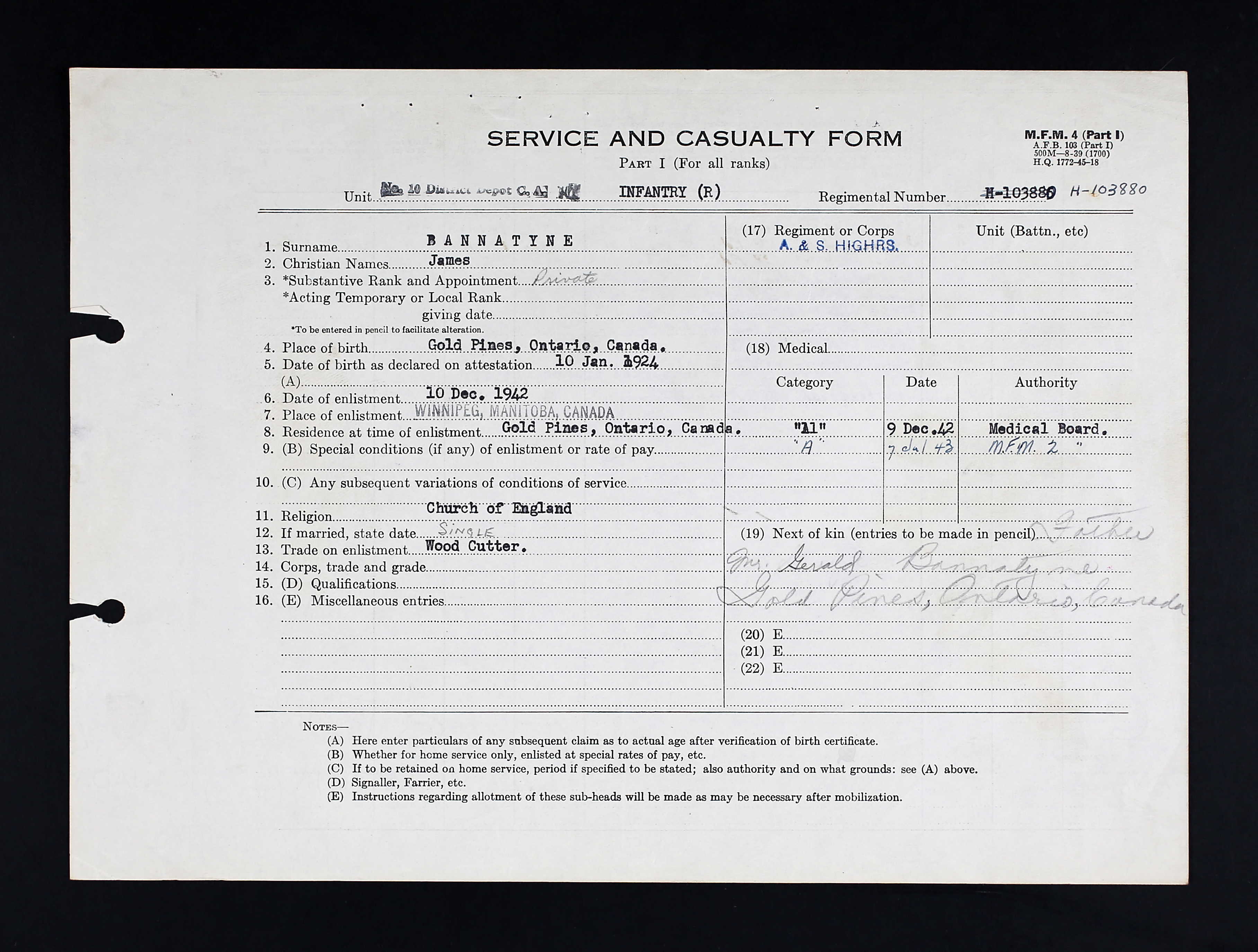

Service and Casualty Form, Pte James Bannatyne.

Gerald married Annie Capay (1903-32) on 23 November 1920 at Lac Seul. Some records give her name as Sapay or Capay Sapay; a family tree gives her father as Alexander Sapay (1878–1935) of Lac Seul. It is Capay on her wedding certificate. They had four sons: David (1923–56), Isaac (1923–49), James (1926–44), Alexander (1929–2002), and William (1931–49); and one daughter, Anne (b. 1927). The children were born in various spots in the Lac Seul area: Webster, Hudson, and Gold Pines. Annie died of tuberculosis on 15 November 1932 (however, one form in James’s personnel file gives 7 April 1931 as the date of her death); she was buried in the Gold Pines Burying Ground (now part of Ear Falls).

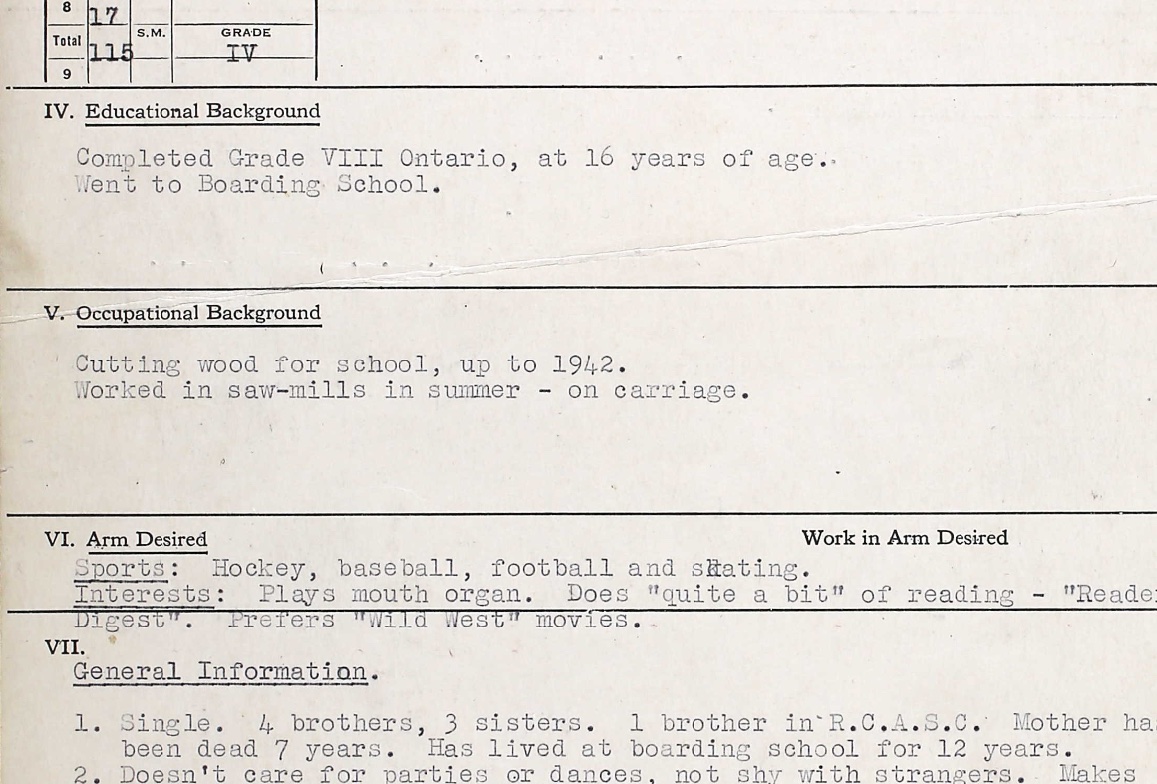

Hudson became a railway point in 1910 with the opening of a station. Subsequently, it was a hub of transportation to the surrounding area by way of various types of boats. The Red Lake gold rush of the 1920s enhanced its local status. The owners of the gold mine lobbied for the construction of a hydro dam at Ear Falls to supply the mine with power. In 1929 the construction of the dam flooded Lac Seul, with a calamitous effect on the indigenous communities, both their livelihoods and their culture, over the next five years. Their traditional burial ground at Ear Falls was washed away. Kejick Bay, for example, became an island (a causeway was built in 2009). Many families lost homes and wild rice beds were destroyed. There was no prior consultation and they derived no benefit from the new source of power. It was decades before the Lac Seul Ojibwe communities were connected to the power grid or compensated for the dam’s impact upon their lives and livelihoods. Chief Clifford Bull told of the effect in 2018:

When I talk about total devastation, I mean there were 80 homes that went under … our sacred grounds, campsites, burials were washed up and bones were exposed — skulls were exposed — and that continues to this very day.

The Federal Court of Canada awarded Lac Seul First Nation $30 million in 1991; 30 years later, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled again, deeming the flooding of 11,000 acres, or 17 percent of the reserve, egregious “even by the standards of the time.”

Ear Falls before and after the dam, 1940s.

“responsible for teaching the many indigenous ways”

James was born in Gold Pines (now part of Ear Falls) on 10 January 1926 (his army records have the same day and month but with 1924 was the year). John Young, a prospector’s guide in the Lac Seul and Red Lake Districts, recalled that he “often played violins for dances at Gold Pines” with his friend, Gerald Bannatyne. Evelyn Sapay, Gerald’s sister-in-law, remembers him as a “real gentleman” who “spoke Ojibwe fluently.” He was a trapper and loved to play the violin. Cecile Bannatyne, Gerald’s great-niece, recalled going with her father to visit Gerald in Gold Pines so that the two could play their violins. She describes the Bannatynes as quite musical. Gerald and his wife, Christine, were fondly remembered by his granddaughter, Irene Bannatyne (Mullin), James’s niece. Her obituary provides a glimpse into Gerald and his likely influence on James:

Growing up in Gold Pines, Ontario, Irene went hunting and fishing, and spent time with her father at the trap line and was proud to be an indigenous woman. She was extremely close to her grandparents Gerald and Christine Bannatyne [Christine Sapay (1910–99)]. Both Grandparents were responsible for teaching the many indigenous ways by making snowshoes, tanning moose and deer hides, and many hours in the woods picking blueberries with her grandmother who also taught her to make Bannock.

“proposed New Industrial School at Sioux Lookout”

In 1920 an amendment to the Indian Act (1876) made it mandatory for indigenous children to attend residential schools. The purpose of these schools was to assimilate, Christianize, and educate (at an elementary level) indigenous children. There were a number of schools in the Kenora District operated by various churches. In 1921, Ontario’s population was 2,933,622, of which 5,407 lived in Kenora. It was the largest territory within the province and had the lowest population density; by 1941, Kenora’s population was 7,672.

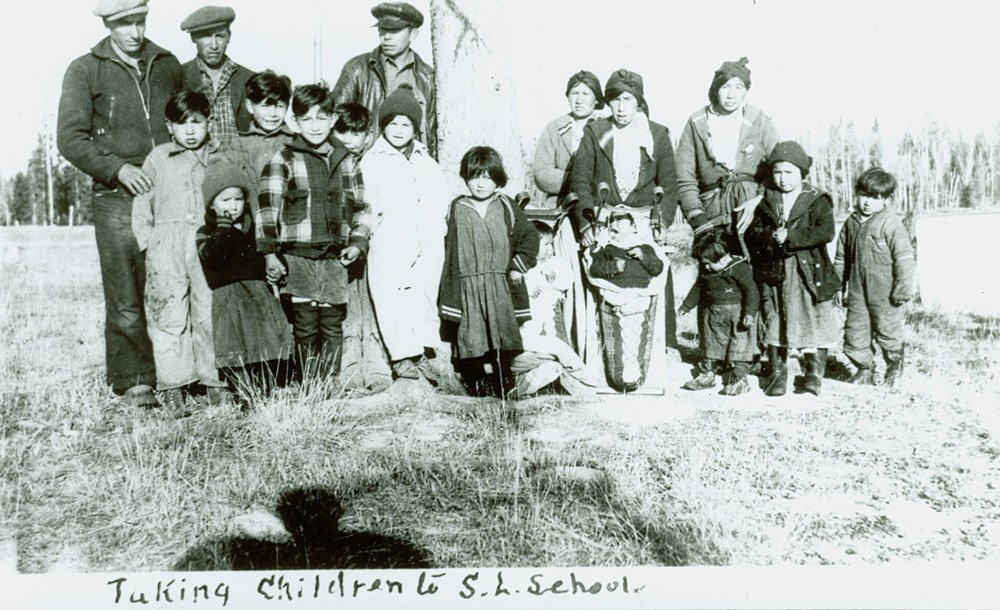

On 7 October 1925 the Department of Indian Affairs urged awarding a contract for materials for the “proposed New Industrial School at Sioux Lookout.” The Sioux Lookout Indian Residential School (later called Pelican Lake Indian Residential School), run by the Church of England, operated from 1 September 1927 to 30 June 1978. Like the territory itself, the school was isolated: 400 km east to Winnipeg, 10 km by boat to Sioux Lookout, and 3 km to the nearest CNR station. Moreover, the staff was small, with just two teachers, and the funding minimal and inadequate. Built to accommodate 125 students, there were only 31 in 1928 and just 103 when fully operable. The school operated on the half-day system, whereby one half was spent in instruction and the other in manual labour of some sort. The boys spent considerable time clearing land and working the farm. As historian Braden Te Hiwi states “a second important element of their [boys’] work was being a ‘woodsman’.”

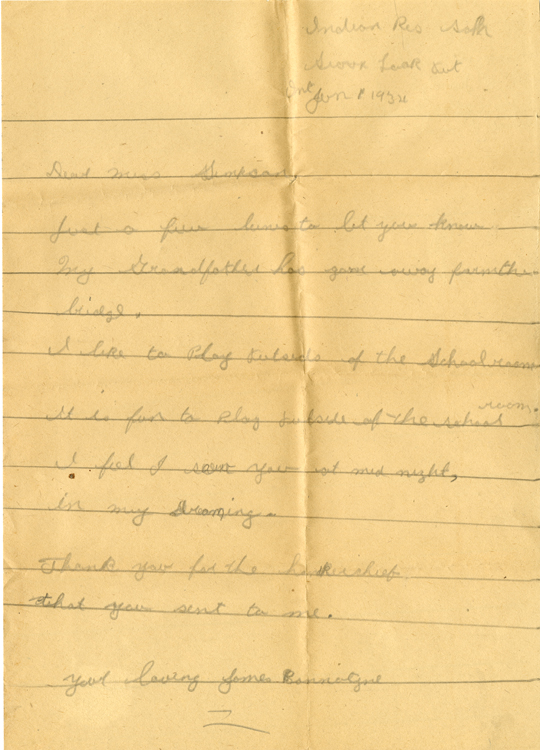

“It is fun to Play outside of the School room”

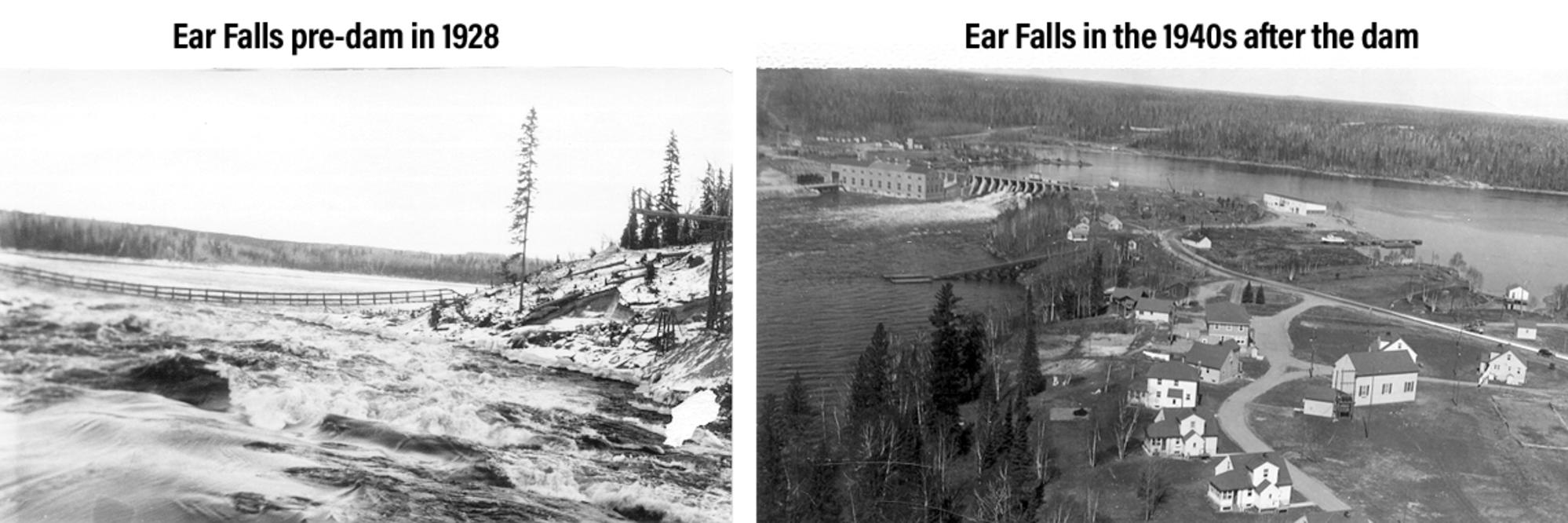

James Bannatyne entered the Sioux Lookout Indian Residential School on 15 April 1931 and his mother died the following year (again, one form in his army personnel file gives her death as 7 April 1931). “Eradication of language was, “Te Hiwi notes, “a key target for the destruction of Indigenous cultures and was a difficult experience for students.” In James’s case, the school failed. There was also an athletic component to life at the school. During the 1930s, school officials applied twice for funds for equipment and relied mainly on donations raised by the church. Jane Simpson taught at several residential schools, including Sioux Lookout. The Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre at Algoma University has an archival collection for her, which includes a number of letters to her from students in 1934. The circumstance under which they were written is unknown and, as the centre cautions, they may have been form letters or part of a writing exercise. As the image of “Jane’s boys” circa 1932 shows, James was one of this grouping. He wrote that “My Grandfather [presumably Alexander Sapay (1878–1935)] has gone away” and “It is fun to Play outside of the School room.” He thanked her “for the hankerchief [sic] that you sent to me.”

Note to teacher Jane Simpson.

“beautifully situated and is in splendid condition”

According to Te Hiwi, most students in the early 1930s were in grades 1 and 2 and, by the later 1930s, most were in 3, 4, and 5. J.D. Sutherland, the acting superintendent of Indian Education, visited the school in September 1933. “This school,” we wrote, “is beautifully situated and is in splendid condition. The Principal is busy clearing land, using a tractor for the purpose … The only means of reaching this school in summer is by motor boat.” Students cleared a part of the school’s 287 acres for farming. On 29 September 1936, a fire broke out in the engine room of the main building leaving it without light and water and requiring immediate expenditures to repair the light and water systems. Elder Evelyn Sapay (the youngest sister of Christine Sapay who married Gerald Bannatyne) attended the school from 1936 to 1944. She “spoke not a word of English.” Students were strapped whenever they spoke Ojibwe. She was “strapped [I] don’t know how many times.” Three of her older sisters were at the school. One day when visiting them with her mother (who spoke no English), “they pulled me out and they just grabbed me and cut my hair.” “They used steel combs, which made me cry.” Students went “back to [our] homes in the summer” and her mother visited often. Evelyn had her sisters; she “had three girlfriends,” and “was the teacher’s pet.” There were sports – “I was the last to get skates” – and girl guides and scouts. There was also “six older girls, like a gang, and we were scared of them, they’d beat you up.” “Boys were on one side of the dining room, girls on the other, and we couldn’t talk to each other.” We “spoke Ojibwe when outside and no one was around.” Jessie Bull, another student there, albeit later, was also defiant: “I used to get strapped for talking Indian. I swore never to give it up.”

Evelyn Sapay met the Queen during the royal tour by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. They travelled by CPR westward and then eastward from 17 May to 15 June 1939, stopping at all major cities and many small towns and spots along the way, one of which was Sioux Lookout. The whole of the residential school turned out for the visit, “girls on one side, boys on the other.” “The Queen wanted to see papooses in cradle boards.” Evelyn’s mother “picked me up to see the Queen and [we] walked by track to Sioux Lookout.” The “Queen came along and asked my name, how old I was – she was alright.” It is possible that James Bannatyne was there that day as well although Evelyn does not remember him from the school.

There were problems at the school with maintenance. The Reverend John Frederick James Marshall, the school’s principal (1926–40), wrote to the local agent for Indian Affairs on 10 April 1941:

… the outside of the main school building is deteriorating from lack of paint … last painted in 1929 … The last few winters the school has been very difficult to heat especially the north side while a north wind is blowing. At times we have to move children to one of the other back rooms and also had to utilize the Chapel in this connection.

Marshall had a quote for “Insul-Brick,” which would, he hoped, provide both insulation and fire-proofing. Moreover, there was a need, he thought, to present a better visual appearance as well:’

… the road is now completed from Sioux Lookout to the Trans Canada Highway and the last few summers we have had a large number of American Tourists coming out to go through the building and it is certainly most unsightly.

“Good”

The quarterly return for December 1941 provides some background on James. He was then 14, from “Fr.Head 219,” and in grade 8. His standing was “Good.” He was, it should be noted, the school’s only student in that grade; he was also the oldest student in the school. There were 2 students who entered in 1934, 3 from 1935, 3 from 1935, and 19 from 1937. All students from 1934 to 1936 were in grade 5 and all had a good standing. That quarter James spent 91 days in school and was absent for 21. On 26-27 December he had a “Holiday.” There were other students from Frenchman’s Head: two Sapays (his mother’s family) and two Hills. James was now listed as a “Fair” student. In the return for September 1942, with James no longer in attendance, there was no one in grade 8. Braden Te Hiwi concludes that “classroom instruction was a failure.” Evelyn Sapay agrees: “it wasn’t easy, [we] had to work half of the day.” Jessie Bull shares her assessment: it was “hard work for half the day and I wanted to be a nurse.” Both deemed the education – in part because of the half-day system – a failure.

Communicable diseases were a persistent problem. There had been a local outbreak of influenza in 1920 and one of tuberculosis two years later. During James’s years at the school, tuberculosis was a persistent scourge, often resulting in the death of young children. Measles and whooping cough also took their toll. On 24 September 1940, the Reverend T.B.R. Westgate of the Indian and Eskimo Residential School Commission of the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada visited the school and reported that “about forty of the children were afflicted with measles.” He was told that “they brought the disease with them when returning from their summer vacation, and that it was now reported to be widespread in the semi-remote Indian settlements from which they came.” There were “approximately one hundred” children in the school “with prospects that all would gradually be afflicted.” Children received modest care first at the school, then at the hospital in Sioux Lookout, or the sanatorium in Fort William (Thunder Bay). The return for June 1942 (the last on which James appears) has 7 children in hospital, 2 in the sanatorium, and 3 who “did not return.” Of their time at the school, Jessie Bull states, “it still hurts when I think about it.” Evelyn Sapay prefers not to remember it: “sometimes I cry when I think of it.”

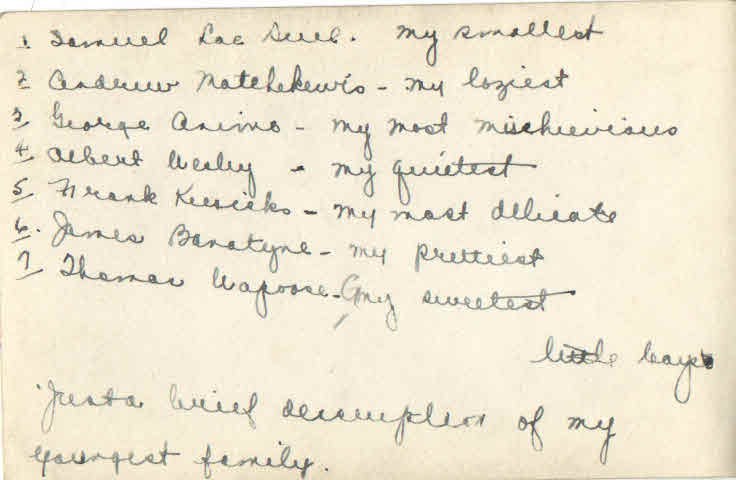

The scant information for James Bannatyne’s life in the records of the residential school is augmented substantially by his army personnel file. His army examination of 14 January 1944 provides some detail for his occupational activities before the army. He was a “Woodcutter from Oct – March last year” for the “Hydro-electric Power Comm[ission]” at Ear Falls. He earned $15 weekly. Concurrently, he worked as a “Fire fighter” for the “Ontario Forestry Branch” at Sioux Lookout. An earlier army record states: “Cutting wood for school, up to 1942. Worked in saw-mills in summer – on carriage.”

“Ojibway”

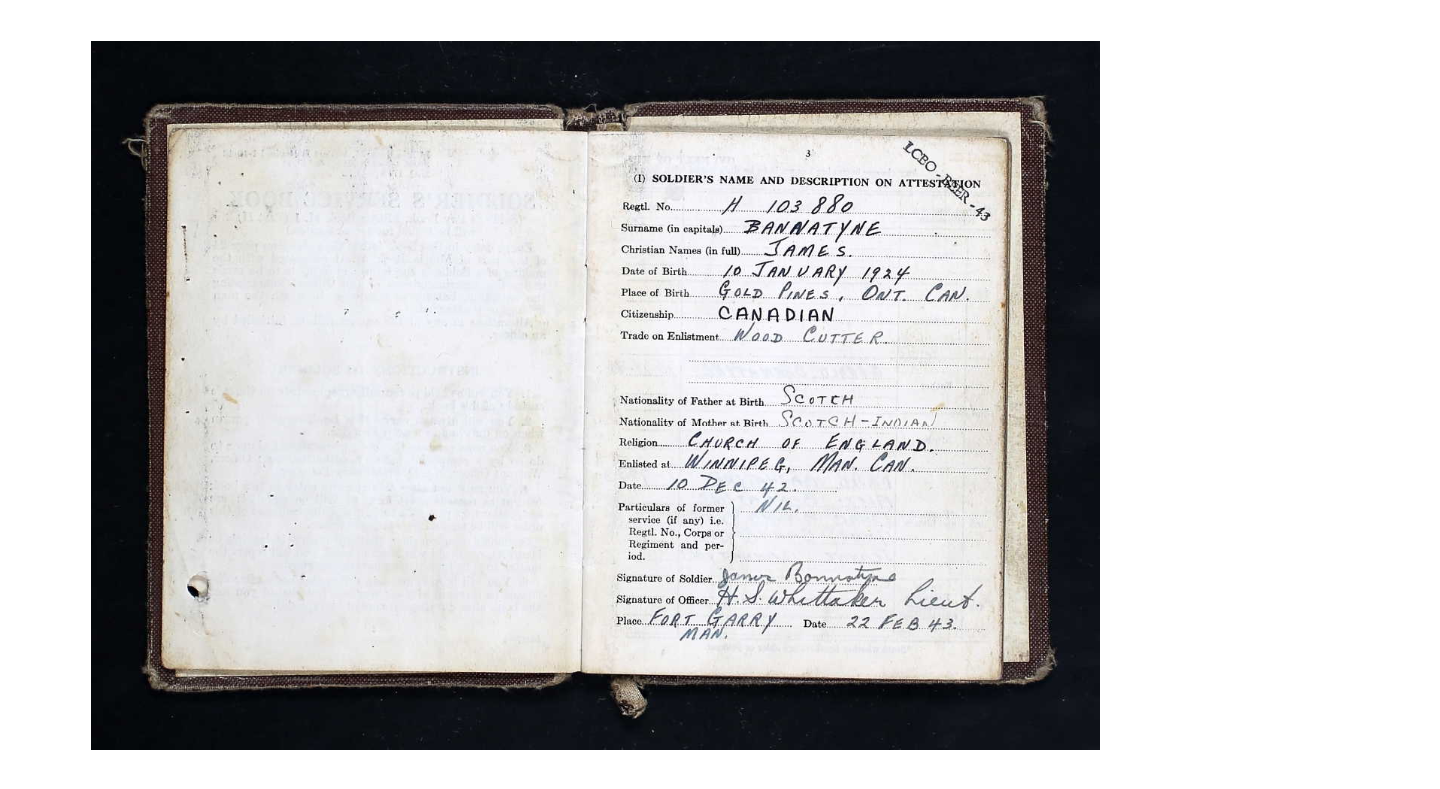

James Bannatyne enlisted in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on 10 December 1942. His “Q” card, dated 9 December provides a bit of detail about his life. His medical category was A1 and he spoke “English & Ojibway.” The various tests for literacy, numeracy, and mechanical aptitude revealed: “average learning ability =. 38/61 non-language sub-tests”; “Near average mechanical interests. 36/65 sub-tests”; “Limited vocabulary – 31/85.” He had no military background and completed grade 8 in Ontario at 16 years of age. Went to boarding school.” He played hockey, baseball, football, and enjoyed skating. His interests were varied: “Plays mouth organ. Does ‘quite a bit’ of reading – ‘Reader’s Digest’. Prefers ‘Wild West’ movies.” Under the category of general information, his form reveals that he was single with 4 brothers and 3 sisters; 1 brother was in the RCASC. His mother had been dead for “7 years” and he has “lived at boarding school for 12 years.” James “Doesn’t care for parties or dances, not shy with strangers. Makes friends easily. No preference between male and female companions.”The general information notes “Ojibway. Health has been ‘pretty good’, wishes to be a machine gunner,” and “Answered in monosyllable, quiet manner and mild.” He was 5’, 4 1/2” 131 lbs., with a “Dark” complexion, black hair, and brown eyes. He had a scar at the base of his left thumb and another on his right knee. His occupational history form gives his date of birth as 1924 and states that he left school at 16 or 1940, which is incorrect. Other records give his age at 18 at the time of enlistment (born in 1924). He was, however, still at school in 1942 and had entered in 1931 when he was 5. It is likely that young James lied about his age, as his father had, to ensure enlistment. He gave his employer as an “Indian School” at Sioux Lookout where he worked as a “Wood Cutter.” The school had promised to give him employment upon discharge from the army, which accorded with his own wish. As for “any employment preference or ambition,” he put “Motor Mechanic.”

“Friends had enlisted”

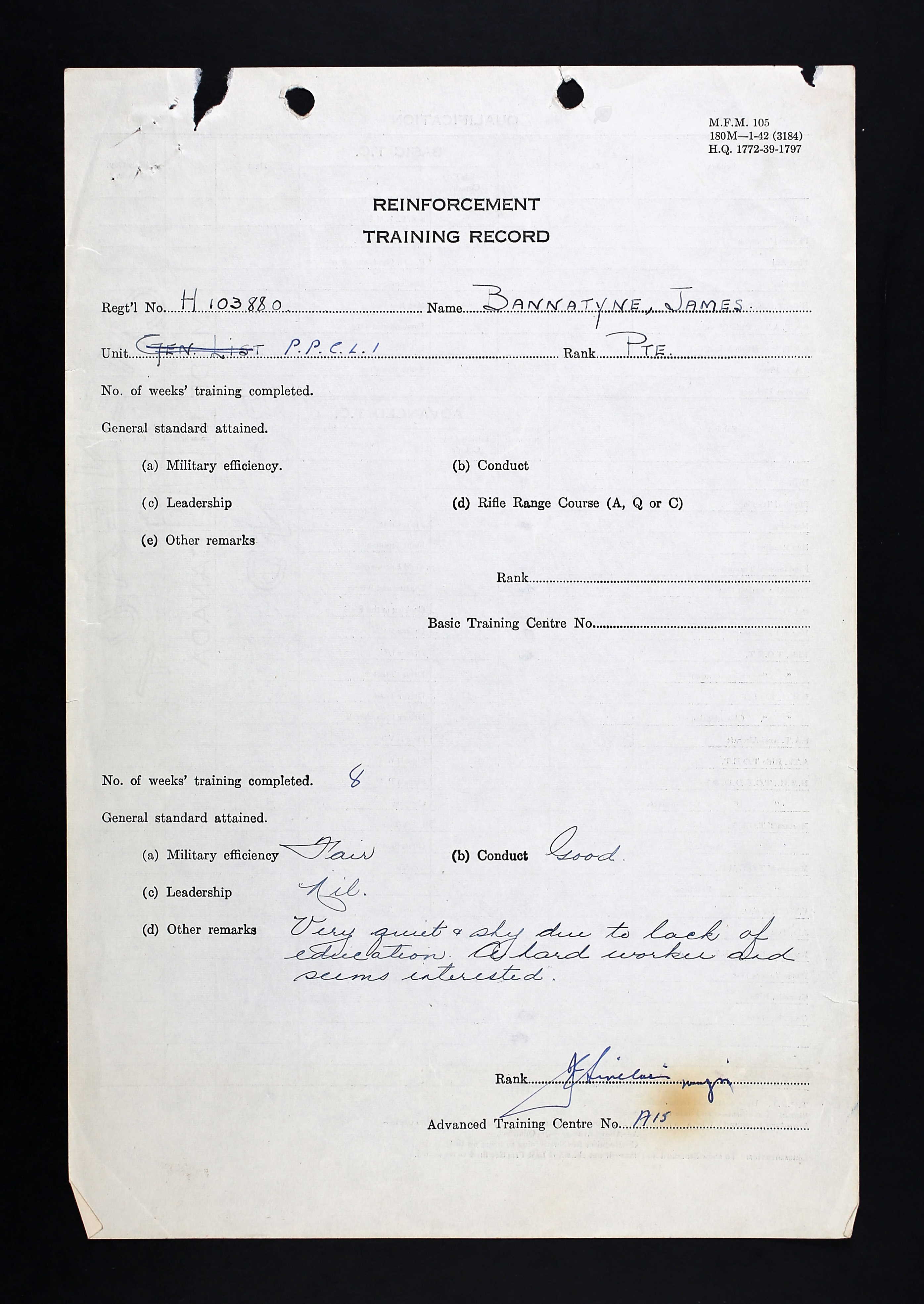

In 1944, when asked by the army interviewer why he had joined, Pte Bannatyne replied: “Friends had enlisted.” On his day of enlistment, he received two days leave without pay, was posted to B Coy of No. 10 District Depot on the 16th, and then granted “New years leave” from 28 December to 2 January 1943 – from “Reveille … until Reveille” as his personnel file attests. On 30 January he transferred to 103rd Canadian Army Basic Training Centre at Portage La Prairie. In an interview at the 103rd on 8 March, the officer noted: “Wants PPCLI. No training difficulties. Likes training. Missed two days training due to eyes – ‘snow blind’ – after route march. Health has been good otherwise.” He received four days leave in February and was taken on strength at A15 Canadian Infantry Training Centre at Camp Shilo on 2 April. At Shilo, the army examiner wrote: “Is 19 years old now. Got a fair education at Indian boarding school. Chooses P.P.C.L.I.” As for the recommendation, it was “Inf; ® Nontr [non-trade]. On 14 April his basic pay was increased by $.10 to $1.40 daily. Admitted to the base hospital on 16 April, he was discharged on the 28th and then transferred to the PPCLI (Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry). His “Reinforcement Training Record” at A15 described his military efficiency as “Fair”; his conduct “Good; and his leadership “Nil.” He was “Very quiet & shy due to lack of education. A hard worker and seems interested.” On 15 June his pay increased to $1.50 daily, the equivalent of regimental pay without a trade qualification.

Reinforcement Training Record.

“blisters and blasphemy were common”

Pte Bannatyne joined the Argylls at Camp Niagara on 5 July 1943 as one of the 152 “other ranks” from Shilo such as Pte Lyall Wright Wotton. Bannatyne was in C Company (see Pte Percy Samuel Hindle). The battalion entrained for Sussex, New Brunswick, on 9 July, boarded the Queen Elizabeth on 21 July, and arrived in Gourick, Scotland, on the 27th. The following day the Argylls were on trains again crossing the border to England during the night of the 28th. The train “arrived at Camberley at 1215 hours. The troops detrained and marched to separate billets – large unoccupied homes.” There were battalion parades, church parades, route marches, passes, medical inspections, leaves, new equipment, and a new training syllabus of refresher courses in every aspect of infantry life. On 1 October, with the new CO, Lt-Col J. David Stewart, who “marched with the men,” the battalion moved to Riddlesworth Camp. “A regimental piper preceded each company as an aid to flagging feet, but blisters and blasphemy were common.” There were more reinforcements on the first day there at, as Pte John Booth expressed it, “the dirtiest camp we ever moved into and it took plenty of work to make it fit live in.” On 2 October another group of reinforcements arrived including Pte Donald Douglas MacKeracher and Pte Welby Lloyd Patterson, a Tuscarora from Six Nations; both were posted to C Coy.

“petty jealousies are not apparent”

Pte Jamie MacRae was another of the new reinforcements posted to C. His letters home provide a glimpse into the life of an Argyll in C Company. He wrote his parents that “the spirit of cooperation and friendliness is much more apparent than in any camp I have in yet which is a pleasant change. On 10 October he wrote that he had “been pretty busy the past week and the training here is plenty tough. We are in the field two days and in the camp one … The fellows here are all nice to be with. They have been together long enough that petty jealousies are not apparent and all are more helpful to the new men.” Seven days later he commented that “Our training is interesting, tough and thorough … discipline is rigid.” On the 19th the battalion was on a major exercise “Grizzly II — Battle manoeuvre in conjunction with tanks is the order of the day with all rifle companies engaged.” The “weather was terrible” and the troops were “wet and miserable.” Capt Bob Paterson, the 2ic of C Company, described it as “awful, absolutely awful … it was all mess up. We had no fires, nothing … and everything went wrong.”

“quartered in large manor houses”

After another large exercise at the start of November, the Argylls moved – “Reveille at 0430 hours – on 6 November to new quarters in Uckfield, Sussex. The various companies were “quartered in large manor houses … The Cedars (‘C’), – all within 5 miles of Uckfield.” The companies concentrated “chiefly on conditioning work – including speed marches” as “life” settled “down into the normal military groove. ”Complaints,” Lt Milt Boyd, the unit war diarist, observed “are chiefly concerned with English heating and plumbing equipment, which falls somewhat short of Canadian standards.” It is worth noting that the heating and plumbing standards of Sioux Lake Indian Residential School were also “short of Canadian standards.” There were leaves, the Pipe Band played “Retreat” for the first time since the Argylls’ arrival in the United Kingdom. C Company held a dance “long postponed due to operations in the field” on the 12th. “Femininity was present in quality and quantity, beer inexpensive and reasonably plentiful, the food appetizing and in abundance.”The Lincoln and Welland band “provided music of the highest calibre” and there was a “jitterbug context.” On 26 November 1943, Pte Bannatyne forfeited two days pay and a pay stoppage in the amount of $3.09 for “equipment lost by neglect.”

“Bright, mild, not aggressive”

There were more new faces, plenty of time on the rifle ranges, more field exercises, new weapons, and Christmas celebrations with parties for local children, Christmas food, and, as reported by Pte MacRae, “every man in our coy had at least one parcel from home and some got several.” On 14 January 1944 the army interviewer described Bannatyne as “Fair” in deportment, “Retiring” in disposition, “Sat[isfactory]” in grooming, and “Fair” in physical appearance. He was “Bright, mild, not aggressive – appears to be of average stability + reliability although socially backward.” In February the battalion moved to Inverary, Scotland, for amphibious training. There was more work on ranges, marches, new equipment, inspections by an array of dignitaries including King George VI and Prime Minister Mackenzie King. On 19 May 1944 Bannatyne forfeited seven days pay for being AWOL, a rare misdemeanour on his part. The last weeks in England were a time of anticipation as first the invasion, then the Argylls’ movement to France and its battlefields became closer and closer. Pte Bannatyne embarked in the UK for France on 19 July and disembarked two days later.

“First casualties … Coy Despondent – realize that its war”

The battalion’s move to the front was not immediate but the signs of war were everywhere. The sight of the destruction of Caen made a powerful impression. The Argylls and C Company took their first casualties on 29 July. CSM George Mitchell of C Company noted cryptically in his diary: First casualties – P. Hindle [Percy Samuel Hindle] – McCann [Pte William Daniel McCann]. Coy Despondent – realize that it’s war. Enemy shelling hot and heavy.” The next day C Company took “over position at Bras,” Mitchell wrote, “Shelling heavy – boys [sic] spirits better.” Capt R.D. “Pete” Mackenzie thought that “by the time you get there – you get into battle, that is – you’ve become a pretty close-knit group already. Now mind you, when you start seeing people killed around you … it reinforces the closeness of those who are still there.” At Bras, although subject to “pretty heavy shelling, both day and night,” the unit was still about 3 miles “from the enemy.”

“… there were dead bodies laying out”

During the night of 1 August, the Argylls “marched” to Bourguébus. Maj Hugh Maclean who was badly wounded there declared that “There is no doubt that Bourguébus … was an extremely unpleasant place.” There was “at all times a heavy mortar barrage” and “at more or less regular intervals, 88-millimetre shells landed here and there in and the village as well. All this kept up ceaselessly …” The war diarist recorded that the “new position was a particularly harrowing one, especially for troops who had only a breath and rather mild battle inoculation.” Pte Whit Smelser of the Intelligence Section (I Section) characterized the “most unnerving trip I had in the whole friggin’ war because you just wonder when it’s gonna go in your back.” Pte Tom Sayer, a sniper in B Company, never forgot the night because they traversed over fields on which the Lincoln and Welland Regiment had fought the Germans: “… there were dead bodies laying out. Of course, we sneaked through in the middle of the night. But you’d be stepping on these bodies and they’d been in the sun, and gas coming out. That wasn’t too good …” Piper Dick Gillespie was a stretcher bearer attached to C Company. For him, the night move into Bourguébus was “utter Hell? We as S.B. [stretcher bearers] never got any more than 1 or 2 hours sleep in any 24 hour period during the entire … [time] that we were in that position.”

Soldier’s Service Book, Pte James Bannatyne.

“Bannatyne killed”

On 2 August, the unit war diarist observed that “The town of Bourguébus was almost a complete shambles… A command-post was set up in a dugout, reinforced by heavy timbers. The companies took up positions on the perimeter of the town: “A” and “B” Companies being forward, “C” and “D” Coys. in reserve. The weather was extremely hot and dry. Vehicles travelling along the roads raised clouds of dust that immediately brought down heavy fire …” Four Argylls died that day and 14 were wounded. C Company absorbed its third death. CSM Mitchell’s terse notes tell the story: “Shelling terrific — [Major Gordon] Winfield [OC, C Coy] shows true colours (yellowish)[.] Bannatyne killed. Enemy snipers … Shelling still terrific — difficult to move around.” It is not known how Pte Bannatyne died, possibly from shell fire, possibly from a sniper as was Pte Jabez G. Holyer.

Maj Maclean believed that “morale stayed high” and “for all the danger,” casualties were “not yet extensive, and learning all the time, the Battalion was rapidly acquiring battle-sense.” For Pte Bannatyne and the others killed that day, there was no more learning to be done. The Argyll dead were, as Capt Claude Bissell put it, would join “a shadowy company” that grew in numbers throughout the months of battle. Pte Bannatyne and the three others killed that day [Ptes Emile Bernard, Herbert Bradshaw, and Holyer joined Ptes Hindle and McCann as the company’s unfortunate first recruits.

The Argyll padre, H/Capt Charlie Maclean, remembered Bourguébus vividly. From the outset of battle, he found a place for himself in the “sick bay” of the Regimental Aid Post (RAP). The “Germans had that taped. And we were shelled regularly, several times a day … we had quite a few casualties there, and I had to go out and bury them. I remember we’d just bury one and then there’d come some of these Moaning Minnies, and you’d hear them coming. Well, there was no place to dive, except in the grave. And so I dove in the grave beside the [dead] fellows, who were pretty high [decomposed] by that time … I was really scared, and all of us were. And I thought to myself, ‘Well, you did your darndest to get into this business. Now put up with it’ …”

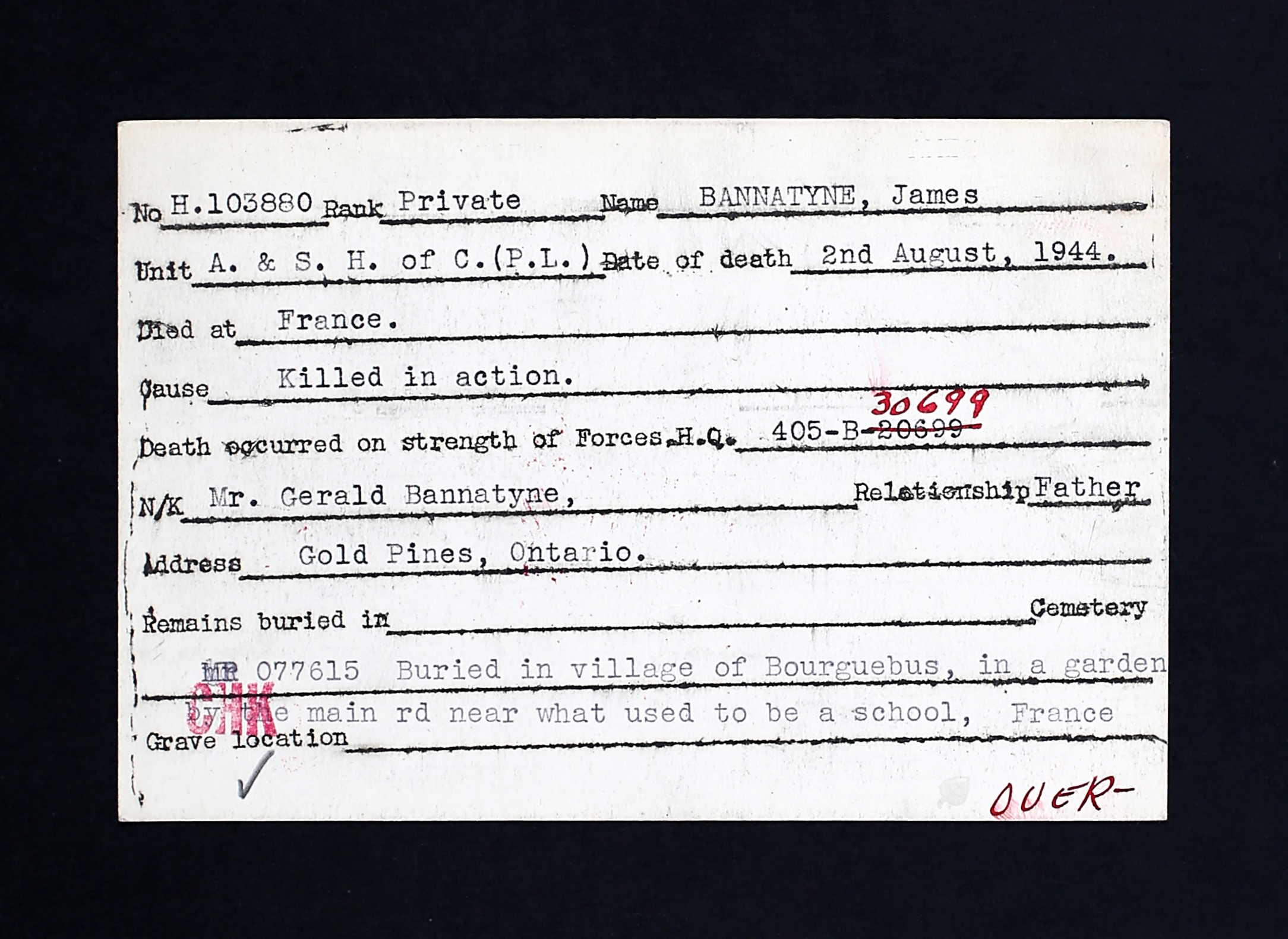

Pte Bannatyne and the other three Argylls were buried in Bourguébus “in a garden by the main rd near what used to be a school.” There was sporadic shell fire while Capt Maclean conducted the service and a regimental piper played the Argylls’ lament, “Flowers O’ the Forest.” C Company and the battalion moved on. They endured more two days of “heavy and nerve wracking” enemy fire at Bourguébus along with “heat, dust, and flies.”The Argylls attacked Tilly-la-Campagne on 5 August. C Company lost 6 killed including, 3 wounded, 2 “Shell Shock,” and 1 “S.I.W. [self-inflicted wound].”

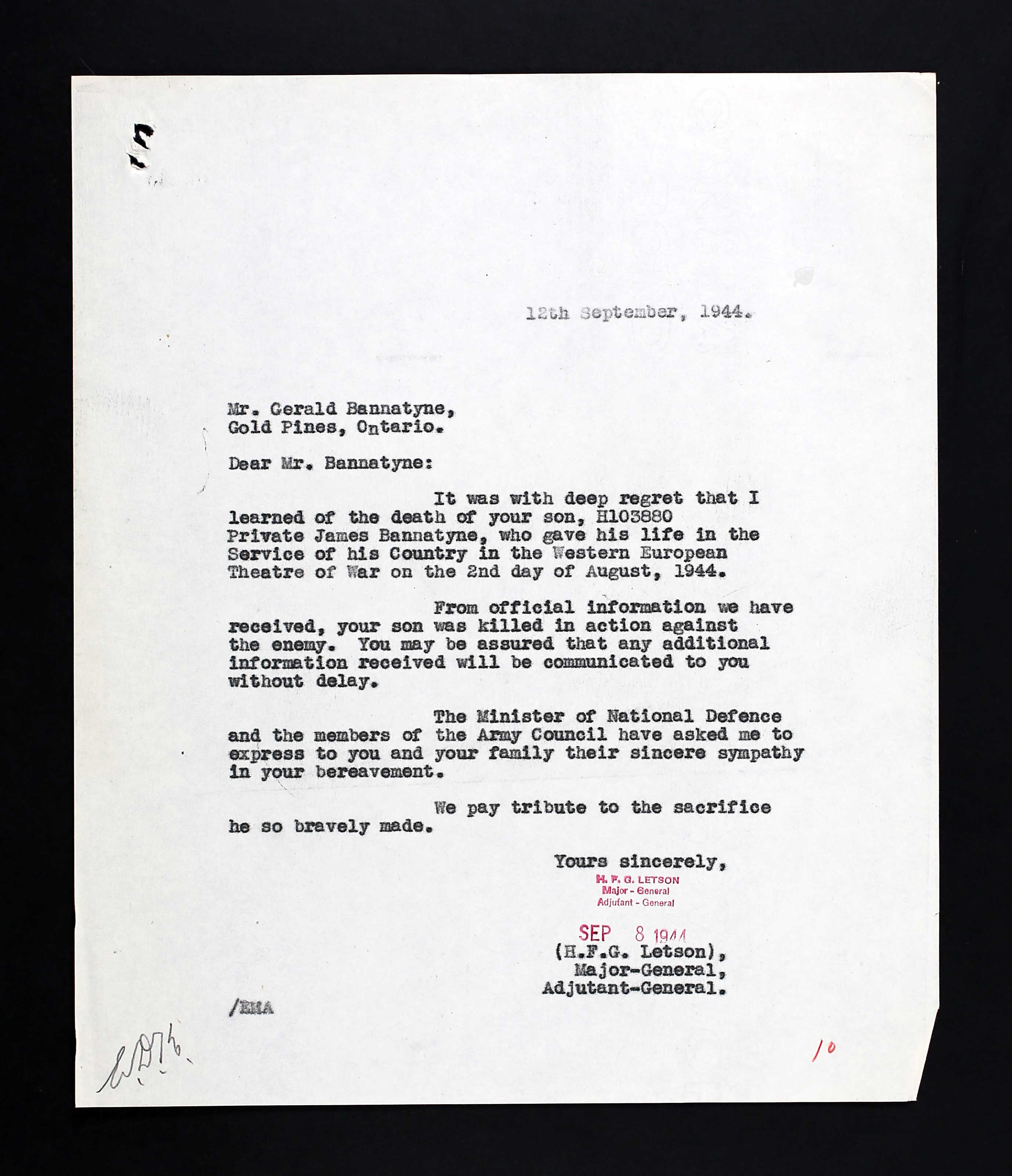

“deep regret … sincere sympathy”

The adjutant general sent a letter to Gerald Bannatyne (who served during the war with the Home Guard) at Gold Pines on 12 September 1944 advising him of his son’s death. In a separate letter Major-General H.F.G. Letson expressed his own “deep regret” and the “sincere sympathy” of the minister of National Defence and the members of the “Army Council.” In terms of personal effects, Pte Bannatyne left little: a red identity disc, a leather wallet, an “A&SH of C emblem, a newspaper clipping, two receipts of $50 apiece for his “5th & 6th” V Loan”, a photo holder, a photo, an automatic pencil, a beer permit, a leather writing case, stationery, and a handkerchief. He left his estate, such as it was, to his father.

Burial Card, Pte James Bannatyne.

Adjutant General to Gerald Bannatyne, 14 September 1944.

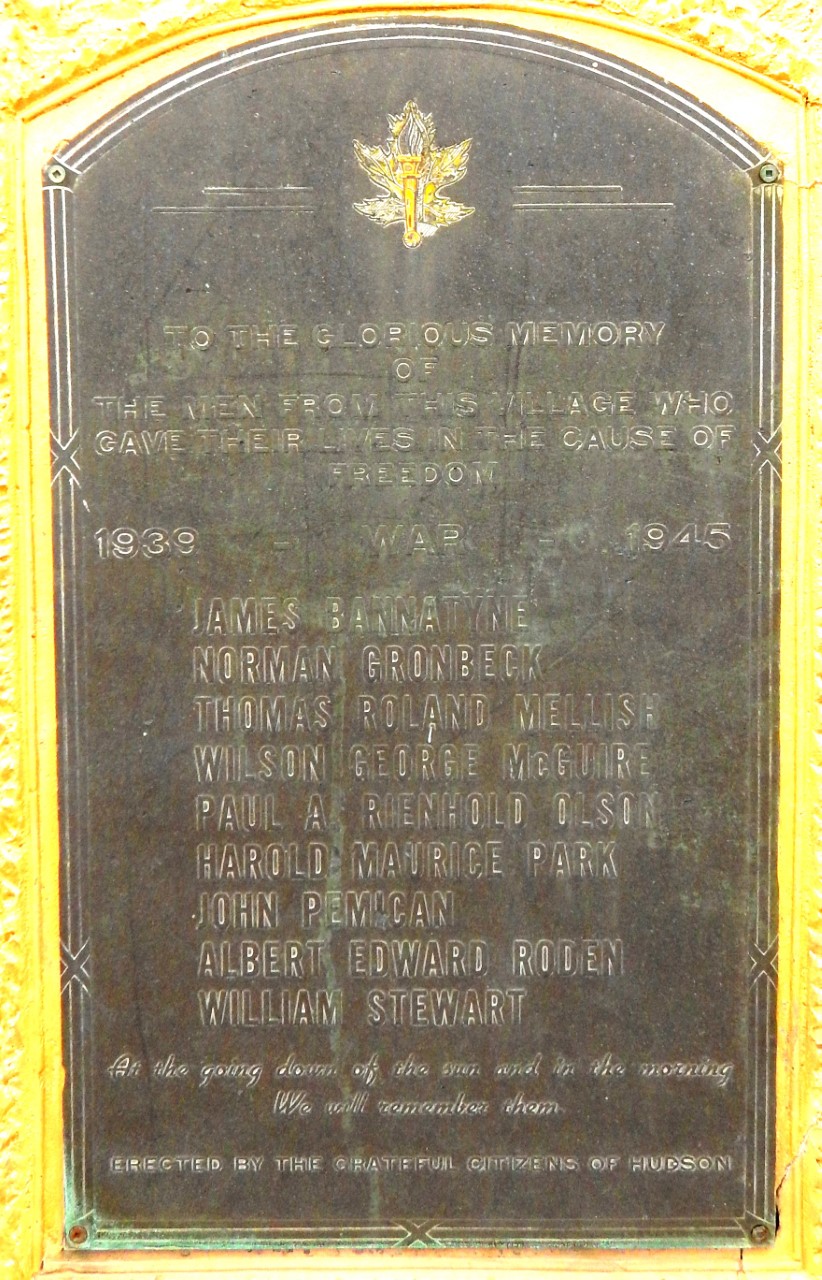

“Fitting that the following notations should be done in red”

James Bannatyne’s name is on the Hudson Cenotaph dedicated to those who gave their live. There is also a memorial to him at Bannatyne Narrows. This famous line — “We will remember them” — from Laurence Binyon’s now iconic poem of 1914 is part of the annual rituals of remembrance. For the most part, the names on lists comprise the act of remembrance. The lives themselves are largely forgotten. It is not deliberate. Rather, it is a benign fact that accompanies the passage of time. Lives fade from memories and often, in the case of the fallen, the memories are unspoken and beyond the reach of oral traditions. Such is the case of Pte James Bannatyne KIA on 2 August 1944 at Bourguébus. His gruff and extraordinary CSM, George Mitchell, took terse notice in his own private diary – “Bannatyne killed.” Mitchell became a decorated Argyll and his prowess in battle was acclaimed by all Argylls. He was “George the Great,” “George the one-man army.” In one of his early jottings (19 July 1944), he wrote: “Fitting that the following notations should be done in red.” In action, C Company and the battalion moved on – there is no choice – and the service of farewell is left to a small Argyll burial party, Padre Charlie Maclean, and the piper playing the lament. Headquarters Company took over the administration of the estate and personal effects, the beginning of a paper trail that worked its way through army administration. Maclean always wrote a letter to the family and often there would be additional letters from the company 2ic (second in command and, in this case, Capt Bob Paterson) and possibly from others in the company or the platoon.

Hudson Cenotaph plaque.

James’s mother died in 1931 or 1932. From then until 1944, he spent the fall, winter, and spring months at the residential school, presumably going home in the summers. Jessie Bull thought of Gerald Bannatyne as “quite the man.” They had bonded because he realized she was a “go-getter” like himself. Gerald lost his sons Isaac (1923–49) and William (1931–49) in the same year; and David (1923–56) disappeared in the bush. In his published recollections of Red Lake, Carl Bleich discussed his neighbours at Gold Pines, Gerald and Christine Bannatyne. Gerald worked for the Department of Lands and Forests, “In the 1930s Gerald would “paddle river systems” and discuss fire prevention with trappers and prospectors. Because of his fluency in Ojibwe and English, he was often used a court interpreter. Gerald had a well-deserved reputation as a story-teller about the Lac Seul area and indigenous ways, as his granddaughter Irene fondly remembered. To Evelyn Sapay, he was “a real gentleman” who “spoke Ojibwe fluently,” was a trapper, and a violin player. He never spoke about James. Gerald and Christine’s cabin at Gold Pines was purchased by Jessie Bull. It was “an old outpost, very old,” “not worth nothing.” Gerald “never mentioned James.” He “showed me [Jessie] his [Gerald’s] war pictures.” She “had heard of someone dying,” but nothing more. Cecile Bannatyne, Gerald’s great-niece, knew that Gerald had a son, “Jimmie.” Gerald did talk about him but “never talked much.” Whether Gerald discussed his son killed in the war with his wife, Christine, or with his brother Charlie is unknown. To date, no obituary of James has been found or image of him as an adult; there is one image of him as a child at the residential school.

Cecile Bannatyne offers one clue. There was a “small suitcase full of pictures and papers” found in the cabin after Gerald died. For Christine Bannatyne, “the love of my life is gone.” She spoke no English and wanted to return to Lac Seul. As for the suitcase possibly containing James’s letters home, it may have gone to the local museum in Ear Falls. According to Cecile, Gerald’s war medals (and possibly James’s) were purchased on eBay in Nova Scotia in recent years.

As next of kin, Gerald Bannatyne could choose an inscription for his son’s gravemarker at Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery. It reads:

AND I GIVE UNTO THEM

ETERNAL LIFE

AND THEY SHALL NEVER PERISH

Within the span of his short 18 years of his life – the army later discovered his real age – young James Bannatyne went from the rugged and beautiful lands of Lac Seul and the Lac Seul First Nation to a grave in what one lyricist called “the green fields of France.” As the poet would have it, he has been remembered.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Note: Pte Bannatyne’s poppy is included in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the middle cluster near the centre. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy for the Field of Remembrance.

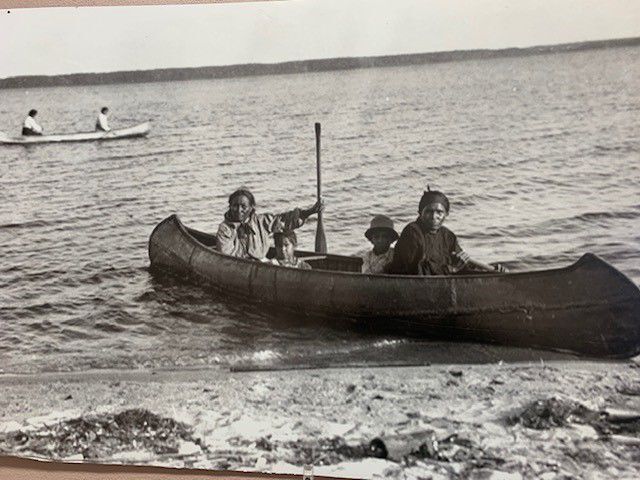

Lac Seul First Nation, 1920s.

Hudson’s Bay Post at Gold Pines (near Ear Falls) on Lac Seul, 1929.

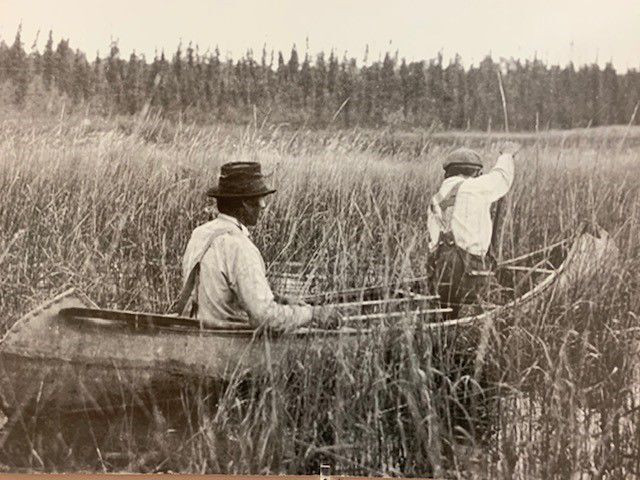

On Lac Seul, 1920s.

Canoeing, Lac Seul First Nation, 1920s.

Aerial view of Sioux Lookout Residential School, circa 1927.

Buildings at Sioux Lookout Residential School, 1940s.

Large group of boys at school, circa 1932.

Jane Simpson’s boys at Sioux Lookout Residential School, circa 1932. James Bannatyne is number six.

Boys at Sioux Lookout Residential School, 1930s.

Pte Gerald Bannatyne.

Taking children to Sioux Lookout Residential School, circa 1940..

Farming at Sioux Lookout Residential School.

Woodcutting, circa 1940.

Tractor at Sioux Lookout Residential School, 1938.

Girl Guides and Scouts Guard of Honour at Sioux Lookout Residential School, 23 May 1940.

Harvesting at Sioux Lookout Residential School, August 1938.

Copy of portrait of Gerald Bannatyne at the Ear Falls Legion.

Aerial view of Pelican Lake Residential School.

Pelican Lake Residential School.

Tank recovery, Bourguébus, France, August 1944.

Gravestone, Pte Gerald Bannatyne 52nd Btn CEF.

Bannatyne Narrows monument to James Bannatyne.

Cenotaph in Hudson.