Lieutenant William Hamilton (Barney) Clendining, MM and Bar, MiD

By LCol (ret) Tom Compton, CD, BA

Director, Argyll Regimental Museum & Archives

William Hamilton Clendining was born on 10 January 1891 at Lisbellow, County Fermanagh, Ireland, to Margaret and Robert Clendining. Barney, as he preferred to be called, emigrated to Canada in 1913, landing in Montreal in September. He is listed on the passenger manifest as a farmer, and it appears he arrived in Canada unaccompanied.

Barney Clendining was one of the original soldiers enrolled into the 19th Battalion, 10 November 1914. His enrolment documents describe him as single, employed as a clerk and with four years of previous military experience in the North Irish Horse.

Pte Clendining arrived with the rest of the battalion at Boulogne on 14 September 1915. Unfortunately, Pte Clendining was sentenced to 21 days Field Punishment No. 1 for corresponding contrary to censor regulations – a harsh punishment for possibly disclosing his location at the time of writing. Letters were routinely read by the officers to ensure operational security and not disclose important information to the enemy if the letter were to fall into the hands of the Germans.

Pte Clendining was Mentioned in Despatches, possibly for his actions during the assault on Vimy Ridge. Clendining was subsequently promoted to Acting Sergeant, 18 May 1917, likely to fill the gaps in Sr NCOs due to casualties.

A/Sgt Clendining was awarded his first Military Medal probably as a result of his actions during the battle at Fresnoy. As was the custom at the time, citations for the MM did not include the details of how the soldier won the decoration.

The Scouts

A few days after getting his first MM, Clendining was confirmed in his rank as Sergeant. Sometime between July and December of 1917, Sgt Clendining was recognized for his second MM with the actual citation published in the London Gazette on 11 May 1918. Again, we do not have the exact details of how he was identified for his bravery. Nevertheless, “Clendining’s talents as a scout were widely known, and it was said that Brigadier-General Rennie himself occasionally summoned him to go out on special assignments.” According to [Lieutenant] Joe O’Neill:

If Gen. Rennie had anything that he wanted to know particularly on a front, he’d send for Sergeant Glendening [sic]. It was Colonel Hatch [sic] told us about it…one time he was there, and he heard Rennie and Glendening they cursed each other up and down, back and forth and they used to do that. He’d send for Glen and get him to go and do special scouting for him, or get his opinion on things.… He depended a lot on this Sergeant Glendening, because he knew that our scout platoon was tops.

Figure 2: The 19th Battalion Association Committee in 1960. Standing: “Bunny” Heron, Bill Doran, Jim Wardlaw, and Fred Stitt. Seated: Frank Griffiths, Barney Clendining, Ted Lang, and Jimmie Wild.

Figure 2: The 19th Battalion Association Committee in 1960. Standing: “Bunny” Heron, Bill Doran, Jim Wardlaw, and Fred Stitt. Seated: Frank Griffiths, Barney Clendining, Ted Lang, and Jimmie Wild.

Lieutenant Joe O’Neill provided more insights into the workings of the 19th Battalion with his recollections of the Scouts:

The 19th Battalion was always very proud of their scout section and we had great reason to be proud of that section, because they had done some marvelous work. Well up in Passchendaele the officer was, his name was Trendell and the scout sergeant was Barney Glendening [sic]. Well they crawled into what was our company headquarters this night … our company headquarters by the way had been a house but the whole house was down. We had a tunnel dug underneath the wall and it came up in the corner of this cellar. They crawled in there and there was very heavy shelling going on, and after we had chatted awhile about odds and ends, Trendell said, “That Passchendaele village up there isn’t nearly as badly battered around as I thought it was.” Somebody said, “You thought, how do you know?” This was before Passchendaele was taken. Oh he said, “Barney and I were up there, why sure we went across through the German line. We got up into Passchendaele village and we even got back in and back a piece and we went into one of the German cook-houses, and here do you want some German sausage?” They had stole the German sausage out of the German cook house and fed us, and of course we naturally had a laugh, we said, “What did you do then?” “Oh we had a funny little thing happen,” he said, “Barney and I thought we’d go back country and see what it looked like back there. They said there was a trench up there, and we were going down this German trench and we met about twenty Huns coming up, a working party coming up, well all we could do was squeeze over to the side of the trench and pull the Harris hats and they said Good-nok, and we said Good-nok [sic] and the whole bunch passed us and by that time we thought we better get out.” They came home. Now it just happened that on the road home, they ran into a German machine gun nest. They found this German machine gun so they figured they’d take it, go out the next night and explore it and go over and take it. So the next night they did go over, the two of them, trying to figure out how they’d take it just the two naturally, the rest were left behind. Well while they were out there, the Germans decided to put on an attack, and they dropped their S.O.S. barrage on our line. Of course our people shot up the S.O.S. it was the battalion next to us, it wasn’t our battalion … and there they were caught between the two barrages. Well as they tried to rush back somebody in this other battalion mistook Trendell for a German and shot him, they thought he was a German. But Glendening, he got back all right, and Glendening was living in Toronto until recently. About a year ago he died, unfortunately, one of the grandest chaps that ever hit our battalion.

Commissioned as a Lieutenant

Clendining was one of at least 66 men who were commissioned from the ranks in the 19th Battalion over the course of the war. Joe O’Neill, who joined the battalion as a junior officer in November 1917, recalled the method by which promising candidates for commissions were selected from among the other ranks in the 19th Battalion. According to O’Neill, battalions would be notified periodically about the number of candidates they were eligible to send to the Canadian Training School for Infantry Officers, which at that time was located at Bexhill in England. Upon receiving word of the appointed number of openings,

The battalion commander would send to the company, and an order would come to, say our company [that] you have the right to send two men to school to qualify for officers. That’s the way the order would come. Now what would happen would be this: the company commander would say, “Now look fellows, let’s sit down after dinner and figure this out.” The officers would sit down, the company officers, and of course everyone had his own ideas who he wanted to promote naturally. We would argue and battle the thing out. We had certain men we were sweet on and another fellow had somebody else and so on. Well finally we would agree, because you knew that whoever you suggested and got his name on that list, that fellow was going to come back and stick his feet under the same table with you later on. He was going to have the next platoon to you in the line and you weren’t taking any chances. You were going to have what you thought was the best man. Then when this was arranged the company commander would send for these men. Well [in] some cases boys didn’t want to be promoted, didn’t want it, others they did. The reason they didn’t was this, that the percentage of the lieutenants killed was away out of all proportion higher than any other rank, and certainly a lot of boys didn’t want it, didn’t want to take a chance on it. But as a rule they did, and naturally they wanted the promotion because we always picked of the best boys there. Well these fellows then, they said, “Yes that would be fine, we’d be glad to have the promotion.” They’d be sent to have an interview with the Colonel, from there they’d be sent to have an interview with the Brigadier, and from there they’d be sent to the divisional commander, General Burstall in our case. He’d have a talk with them, and if everybody was satisfied that this man looked all right, everybody agreed, which was usually the case.… Those men [were] sent over to school in England, then they came back. They came back to your company, and they were officers sitting in the same mess with you and had a platoon right with you, right along side of you, so you weren’t taking any chances.

Wounded in Action

On 14 April 1918, Lieutenant Clendining was very seriously wounded during a skirmish in no-man’s-land. Clendining was leading a [fighting] patrol of 20 other ranks in a raid on a German outpost.… Clendining’s party had no trouble locating their target, which they immediately rushed with the intention of securing some prisoners. The outpost’s small garrison promptly took flight and led Clendining and his men straight into a large German covering party. Once both sides had recovered from the momentary shock, a vicious exchange of grenades ensued, followed by a mad charge by the Canadians. As he ran, Clendining shot one German through the head, and it may have appeared for a few moments that his party would emerge the victors. Suddenly, a group of 60 to 70 more Germans rushed onto the scene, hurling bombs, driving the Canadians back, and wounding Clendining and three of his men. Instead of taking prisoners, it seemed that Clendining and his men might be captured themselves. But the unwounded members of the party managed to drag Clendining and the other injured men to safety, thanks in large part to the fire from a nearby Lewis gun team, probably belonging to a covering party that had been sent out under Lieutenant W. Steward. All members of the fighting patrol made it back to Canadian lines and the wounded men were sent down the line for treatment. Although they had failed to secure any prisoners, they at least were able to prevent the capture of any of their own men. In the end, Clendining would survive his wound, but the battalion lost his services as Scout Officer, a position that must have seemed somewhat cursed, given the unfortunate demise of Clendining’s predecessor, Lieutenant Trendell, earlier at Passchendaele. More likely, it was the nature of the position to attract bold men who were unafraid to take personal risks.

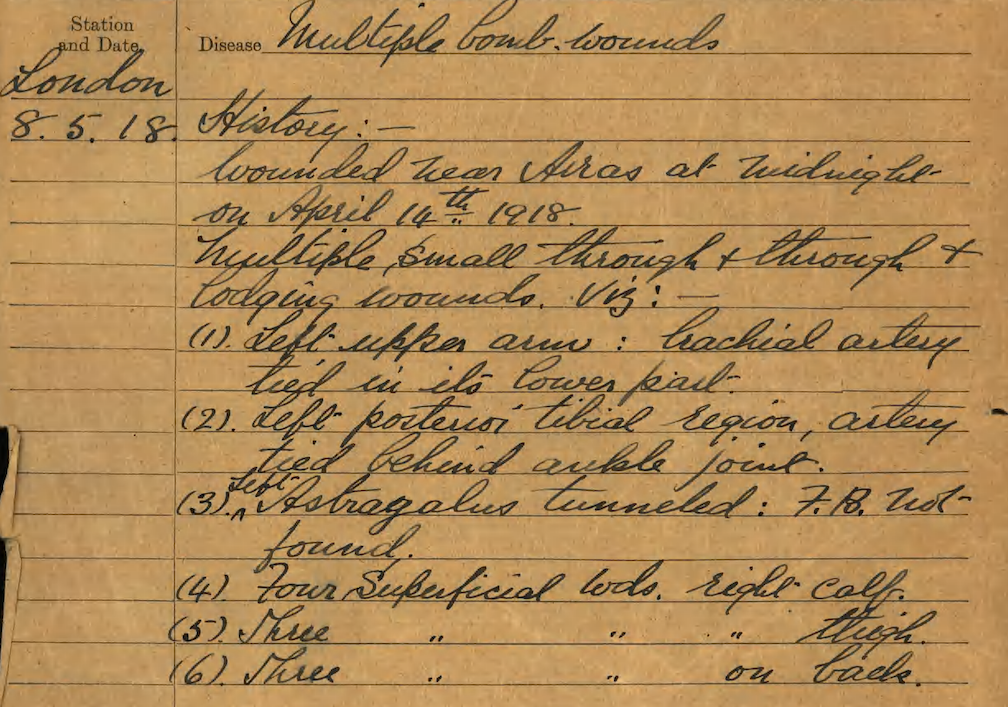

Clendining’s wounds were so severe there was some doubt he would survive but a month after he was hit. The medical staff at the Prince of Wales Hospital in London saw slow improvement. By 4 July 1918 medical staff reported: “All wounds healed but walks with a limp. L[eft] hand and elbow are swollen and limited movement.”

Clendining remained in hospital in England until 10 October 1918 when he was repatriated to Canada and was eventually moved to Toronto General Hospital. Despite a short bout of tonsilitis, Lt Clendining probably decided he’d had enough of hospitals and was discharged. He was scheduled to return for a final medical board, 27 June 1919, to assess his wounds on demobilization but failed to show up, likely tired of dealing with the Army’s bureaucracy.

Figure 3: An extract from a medical report by staff at the Prince of Wales Hospital in London regarding Clendining’s extensive wounds. Source: Library and Archives Canada Personnel Records of the First World War.

Figure 3: An extract from a medical report by staff at the Prince of Wales Hospital in London regarding Clendining’s extensive wounds. Source: Library and Archives Canada Personnel Records of the First World War.

Post War

Barney Clendining was finally discharged from the Army on 6 July 1919. Clendining married Isabel Esther Nelson on 3 September 1924 in Toronto. The marriage certificate listed Barney as an “assistant buyer,” while Isabel was listed as a “private secretary.” He was 33 years of age and she was 24.

Barney died in 1962, while Isabel, who lived to almost 100 years, died in 1989. Barney and Isabel are memorialized on a family headstone in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto (see Figure 4).

Sources

The bulk of this work is from It Can’t Last Forever, the 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War by David Campbell (Waterloo, Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2017).

LAC, RG 41, B-III-1, Records of the CBC, Flanders Fields, Vol. 10, 19th Battalion, Transcript of interview with Joe O’Neill, Tape 4, pp. 1-2, as quoted in It Can’t Last Forever, the 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War by David Campbell (Waterloo, Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2017).

Library and Archives Canada, Personnel Records of the First World War, https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/personnel-records/Pages/search.aspx

Other sources as indicated.

Figure 1: An example of the Military Medal twice awarded to Lt Clendining while he was a sergeant. The medal is awarded to Warrant Officers, Non-commissioned Officers and non-commissioned members for individual or associated acts of bravery on the recommendation of a Commander-in-Chief in the field. Canadians have received 13,654 medals, including 848 first bars and 38 second bars. Source: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/medals-decorations/details/53#

Figure 1: An example of the Military Medal twice awarded to Lt Clendining while he was a sergeant. The medal is awarded to Warrant Officers, Non-commissioned Officers and non-commissioned members for individual or associated acts of bravery on the recommendation of a Commander-in-Chief in the field. Canadians have received 13,654 medals, including 848 first bars and 38 second bars. Source: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/medals-decorations/details/53#

Figure 4: The family grave marker for William Hamilton Clendining and his family. He is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto. www.findagrave.com.

Figure 4: The family grave marker for William Hamilton Clendining and his family. He is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto. www.findagrave.com.