The Horrible Irony of Hyon

By LCol (ret) Tom Compton, CD, BA

Director, Argyll Regimental Museum & Archives

The final casualties of the war included 15 killed in action during the attack on Hyon, Belgium, 10 November 1918. The final full day of hostilities saw soldiers that had made it through the war with the odd wound, sometimes serious, but they would perhaps have been aware that the Armistice talks between the belligerents were ongoing and that an end to the fighting was a possibility. Some may have thought they would make it home alive. Certainly, for their families, the announcement of the end of the war was welcome news, knowing they may see their loved ones return home. The shock with each family, within a few days after the announcement of the Armistice, that their son, husband, or father had been killed on 10 November, just hours before the war’s end, would be the beginning of a grief that was underscored by an awful irony that the soldiers were so close to the end, only to be struck down, their life at an end.

These are the last known officers and soldiers from the 19th Battalion, killed in action on 10 November, the last full day of combat for the 19th Battalion. The memorials include those severely wounded on the 10th and one listed as sick, who would die days or weeks after the war ended.

Lieutenant Wesley Clarence McFaul

Wesley Clarence McFaul was born on 27 March 1891 to Alexander and Annie (née Roadhouse) McFaul, in Owen Sound, Ontario. He was their second son, and his older brother, William Lawrence, had just turned two (being born in 1889). In time, three more children would be born to Alex and Annie: Lillian Viola (1894), Charlotte Evelyn (1895), and Robert Cecil (1897).

School started for Clarence (he was better known by his middle name) around 1896; he attended Dufferin Elementary in Owen Sound along with his brothers and sisters. In 1905, Clarence began classes at the Owen Sound Collegiate Institute (OSCI), and historical documents show that he had an almost perfect attendance record. In the 1919 edition of the OSCI Auditorium – published after his graduation – Clarence and his brothers’ names can be found in the school’s Roll of Honour (on pages 5 and 6 respectively).

Clarence McFaul was an active member of the Methodist church community in Owen Sound. A 1908 photograph shows him in a YMCA Bible study class, and his obituary described him as “upright, [and] God fearing.”

Clarence McFaul’s Bible study class. Clarence is in the back row, circled. Source: “They Served for Us”: Gillian Wagenaar, “Servicemen and Women: Wesley Clarence McFaul.”

Clarence McFaul’s Bible study class. Clarence is in the back row, circled. Source: “They Served for Us”: Gillian Wagenaar, “Servicemen and Women: Wesley Clarence McFaul.”

Clarence’s mother, Annie, passed away in January 1914 due to a combination of uterine cancer and bronchitis. At this time, the McFaul family was living at 922 2nd Avenue West in Owen Sound, having moved there at some point after 1911. They also owned a store at 912 2nd Avenue East – a main street grocery shop known as McFaul’s. Clarence was working there as a clerk when, in November 1915, he enlisted in Peterborough, Ontario, to fight in the Great War.

Originally a member of the 31st Grey Regiment, Clarence McFaul was assigned to the 93rd Overseas Battalion, CEF. He, along with hundreds of other young Canadian men, embarked from Halifax aboard the S.S. Empress of Britain on 15 July 1916. They would arrive in Liverpool ten days later, on 25 July. From there, Clarence would be transferred to the 19th Battalion.

Clarence was wounded in the assault on Fransart, 18 August 1918, receiving a gunshot wound to the right arm. Two days after the incident, he was admitted to the Order of the Daughters of the Empire Hospital (located at Hyde Park, in London), where he spent several weeks. After that, he was sent to the Officers’ Convalescent Hospital (Matlock Bath, England), where he remained from 19 September 1918 to his discharge date of 25 September. According to war diary data recorded for the Matlock Bath hospital, the Thursday Clarence arrived was a “pleasant day.”

Wesley Clarence McFaul was killed in action on 10 November 1918, the day before Armistice. The official report regarding the circumstances of his death reads as follows:

“He was standing in the garden of a house in Hyon about 2:30 p.m. on November 10th, 1918, when a shell exploded at his feet, wounding him in the leg and right shoulder. He was rendered unconscious and died about five minutes after being hit.”

Lt. Wesley Clarence McFaul is buried in the Mons (Bergen) Communal Cemetery. He was the son of Alexander Wesley McFaul and his wife, Annie Lavina Roadhouse, of 922 2nd Avenue West, Owen Sound, Ontario.

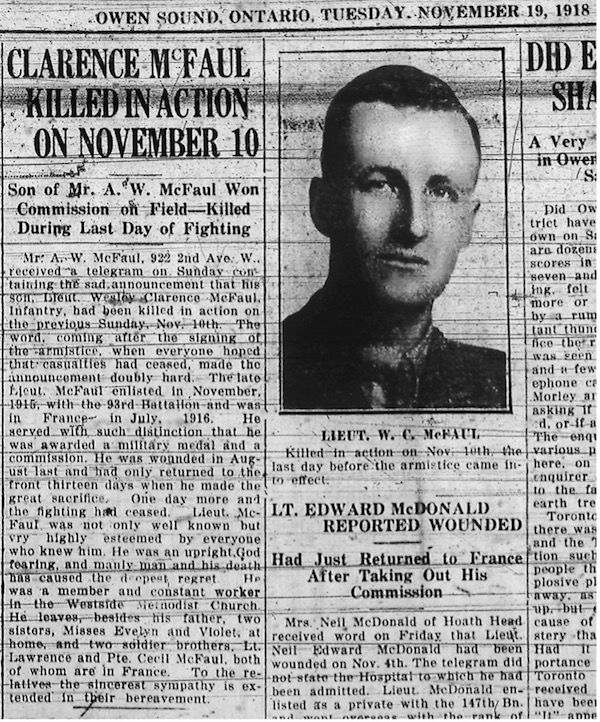

Obituary for Wesley Clarence McFaul. Source: “They Served for Us”: Gillian Wagenaar, “Servicemen and Women: Wesley Clarence McFaul,” from the collection of the Owen Sound & North Grey Union Public Library, clipping 19 November 1918, The Sun Times (Owen Sound).

Obituary for Wesley Clarence McFaul. Source: “They Served for Us”: Gillian Wagenaar, “Servicemen and Women: Wesley Clarence McFaul,” from the collection of the Owen Sound & North Grey Union Public Library, clipping 19 November 1918, The Sun Times (Owen Sound).

Corporal John Abraham Simon, Regimental Number 124732

Cpl John Simon was born 6 October, 1885, in Hamilton, Ontario. His parents were John and Ema Simon of 80 Walnut Street South, Hamilton. Cpl Simon married Ida May Simon in 1906 and they had a son, Russell Bruce Simon, in 1907. John Simon’s enrolment documents describe him as having “three years with the Canadian Militia” prior to enrolment and that he was working as a mechanic in Detroit, Michigan, up until 15 April 1916, when he crossed the border at Windsor and enrolled in the 70th Battalion, CEF. John was absent without leave on 15 May and received 48 hours detention for the brief infraction. Shortly thereafter, he was shipped overseas to England, where the 70th Battalion was broken up for reinforcements; John Simon was transferred to the 19th Battalion. He was recognized for his qualities as a junior leader and was promoted to Corporal in October 1916.

John was with the 19th Battalion at Vimy Ridge, and while he made it through the initial assault unscathed, he received a gunshot wound to the left shoulder as the unit was holding the Red Line near Les Tilleuls. Following his convalescence, he rejoined the 19th Battalion but was killed in action as the unit was attempting to take Hyon. The circumstances of his death are reported as: “Instantly killed in the town of HYON by machine gun bullets through the neck and left chest.” No doubt the same machine guns that were holding up the entire 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade advance and sighted by the Germans to the south and southeast. Cpl Simon’s son, Russell, has a grave marker indicating he died in 1961 and he is listed a “PFC,” suggesting that he served in the US Army, likely during the Second World War.

Private William Alfred Bell, Regimental Number 56092

Very little is known about this man. He is listed as “Died (Influenza) at No.1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station.” His date of death is 12 December 1918. His unit is listed as 19th Canadian Infantry Battalion. We know he is buried at the Mons British Cemetery in Belgium. Beyond this, there is nothing known. There is no service record on file under this name, and the form describing his circumstances of death is very brief.

Private James Clarence Buttimer, Regimental Number 3231310

James Buttimer was born in Dunmanway, County Cork, Ireland, on 7 December 1893. His parents, Richard and Clara Buttimer, still lived in Dunmanway when he joined the army. James was single and a cashier in Toronto prior to enrolling in the 1st Central Ontario Regiment. He received his conscription notice under the Military Service Act, 1917, received a medical exam in September 1917, and was enrolled on 22 January 1918. He likely performed basic training at Camp Exhibition in Toronto and then was shipped overseas, 19 February 1918. He arrived in the UK at Camp Witley on 4 March 1918. James remained in Camp Witley for just over three months, likely undergoing more training until he was transferred to the 19th Battalion on 20 June 1918.

Pte Buttimer was involved in heavy fighting with the 19th during the Battle of Arras until he received a gunshot wound to the upper lip during the third day of the battle, 29 August 1918. It had been the heaviest month of casualties of the war for the 19th Battalion, which suffered an astonishing 28 officers and 486 other ranks killed, wounded, or missing.

James Buttimer was enrolled in the army less than 11 months when he was killed in action outside Hyon, 10 November 1918. “He was one of a stretcher bearer party, proceeding under cover of darkness in ‘no mans land’ to being [sic] in a casualty, when the enemy opened up machine gun fire instantly killing Private Buttimer.” He is buried in Mons Communal Cemetery, Belgium. The inscription put on his headstone by his family reads, “Faithful Unto Death.”

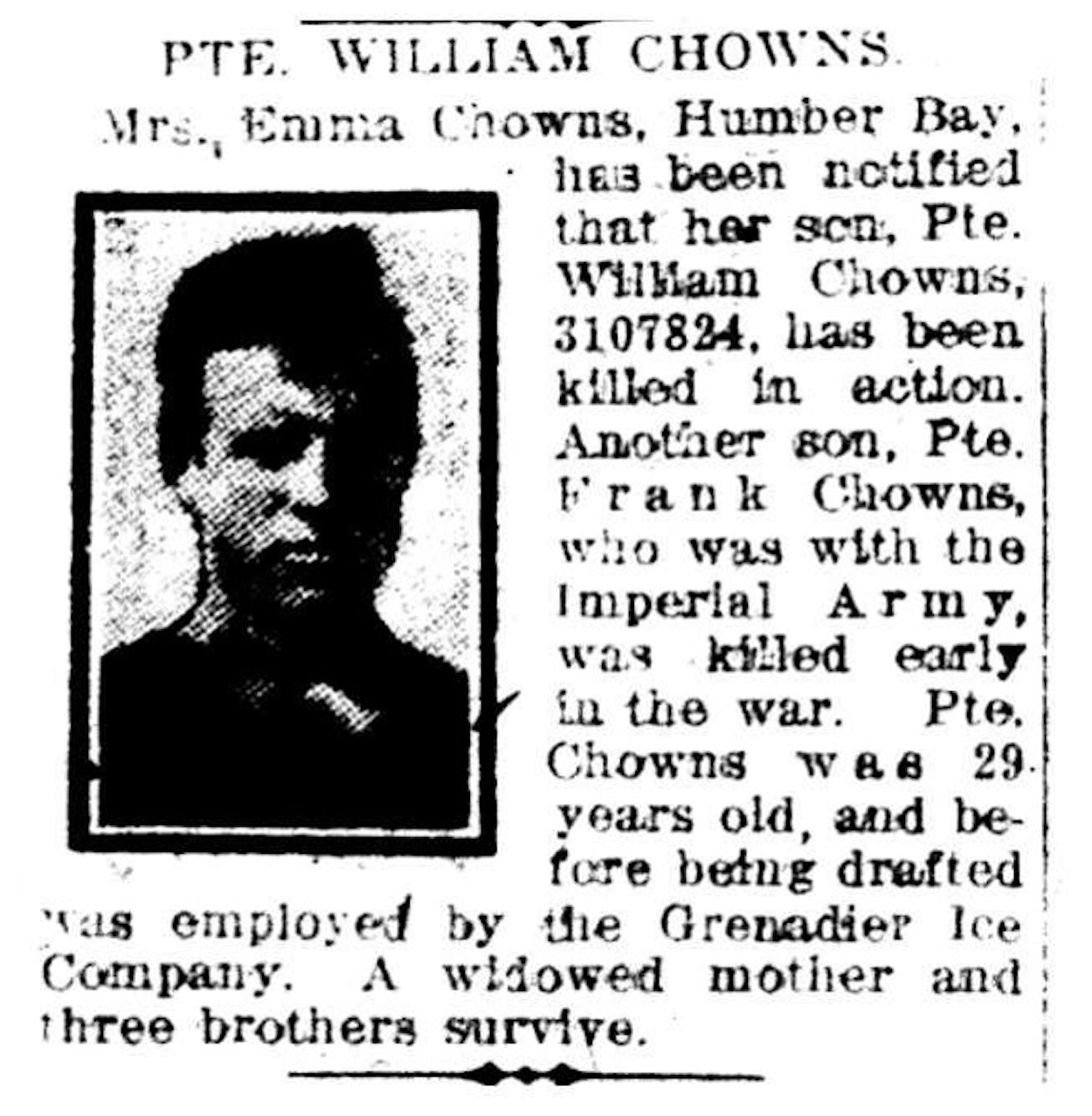

Private William Chowns, Regimental Number 3107824

William Chowns was born on 24 January 1888, in Thame, Oxfordshire, England, to Emma and William Chowns. The younger William immigrated to Canada in 1907 and was residing in Humber Bay, Ontario, with his mother, as a labourer when he received his conscription letter. During his medical examination, he claimed to have lumbago, but the examiner noted there was no evidence of the same. Pte William Chowns was enrolled on 20 February 1918 in Hamilton. He sailed from Halifax on 15 May 1918, arrived in the UK on the 27th, and moved directly to Camp Witley. Pte Chowns would have received additional training at Witley until he was transferred to the 19th Battalion on 19 September 1918. The circumstances of his death are recorded: “Killed In Action, Was instantly killed with a machine gun bullet through the head.” He is buried in Mons British Cemetery, Belgium.

Private Patrick Joseph Cronin, Regimental Number 507414

Patrick Cronin’s enrolment document notes his date of birth as 1 June 1894. It does not list any parents, but does list a Mrs Martin Sennott of Ottawa as a friend and Next of Kin. In his will, Cronin left the effects of his estate to Mrs L. Lafrance, also of Ottawa. It is possible that he was admitted to a workhouse in London, England, at the age of six, but the records are not complete. A memorial web page includes a reference to his possibly being one of the Home Children brought to Canada at the turn of the century.

He lists five months of previous service with the Canadian Engineers on his documents, and he was enrolled on 2 November 1916. Patrick was a diminutive 5 feet 1-3/4 inches with blue eyes and dark hair. He was single and worked as a labourer.

On enrolment he was sent for Signals training, but his service records are very brief as to where and how that took place. He eventually found himself in 4 Division Signal Training Depot, where it appears he got into trouble fairly regularly. Cronin forfeited pay several times, likely for relatively minor infractions, but found himself sentenced to 21 days detention in January 1917. He was eventually transferred to the 3rd Canadian Reserve Battalion in Shornecliffe, on 25 September 1917, and then to the 19th Battalion, 26 March 1918, likely due to manpower shortages in the infantry battalions. Private Patrick Joseph Cronin died during “[a]n attack in the vicinity of Hyon. Killed in Action. Instantly killed by enemy machine gun fire, while advancing with platoon.” He is buried in Mons British Cemetery, Belgium.

Private William Hales, Regimental Number 124752

William Hales was born Portlaw, County Waterford, Ireland, on 12 June 1895. His parents were William and Bridget Hales. Young William emigrated to the United States at 22 years of age in 1915. It appears he settled in Detroit, Michigan, as a labourer. He included in his records that he had served in the “21st Guard Company” for three months prior to enrolling in the Canadian Army, at Windsor, and he eventually enrolled with the 70th Battalion, CEF, on 12 April 1916, at London, Ontario. The 70th sailed soon after for England, and the unit was broken up for reinforcements with other battalions. William Hales found himself transferred to the 19th Battalion and was in combat soon enough. The 19th relieved the exhausted 2nd Battalion troops on 10 September 1916 in the trench lines outside Albert. The Germans attempted several raids that night, during which it appears Pte Hales received, variously, a gunshot or shrapnel wound to his right buttock. His medical documents describe the injury as both.

Hales was sent to the rear and had his wound treated, allowing him 10 days to recover. In October 1917, he was complaining of abdominal pain radiating down to his right testicle. He subsequently underwent surgery for a hernia on his right side and was granted time to recuperate until 21 January 1918. Hales appears to have continued service with the 19th, unscathed, right through to November 1918. His luck ran out on 10 November when “[w]hilst taking part in an attack on the village of Hyon, near Mons, he was hit in the stomach and instantly killed by an enemy machine gun bullet.” Pte Hales is buried in Mons British Cemetery, Belgium.

Private Herbert Howard, Regimental No. 3032285

Herbert Howard was born 4 January 1888 to John and Mary Howard in Chadderton, Lancashire, England. We know nothing about him until 1917, when he described his trade as “Brass finisher” on his enrolment documents. Herbert was conscripted under the Military Service Act, 1917, and was medically examined in Toronto in October 1917, being pronounced “A2” fit. He was sworn in on 7 January 1918 and embarked for England on 13 February, arriving on the 24th. Pte Howard was barely in the army before he was shipped overseas, precluding any sustained basic training while in various transit camps or onboard ship. He was taken on strength by the 3rd Reserve Battalion in Camp Witley, 26 February, where he would have received his first proper military courses in basic training and infantry training. By 10 May 1918, Howard was transferred to a reinforcement camp and waited to be told to proceed to the 19th Battalion, which he did on 19 June. Pte Howard’s records show that he was hospitalized 3 August for diarrhoea but was returned to duty on 7 August, just in time for the opening of the Battle of Amiens for the 19th Battalion at Marcelcave. Herbert Howard remained with the 19th through the tough fighting of the Hundred Days campaign, until 10 November 1918, when he was killed in action: “when his platoon [was] taking part in an attack on Hyon, and whilst advancing through an orchard, an enemy machine gun opened fire and he was shot through the head and instantly killed.” We do not have any images of Herbert Howard or of his headstone, but we do know it bears this inscription from his family: “Until the day break /and the shadows flee away.” Private Herbert Howard is buried in Mons British Cemetery, Belgium.

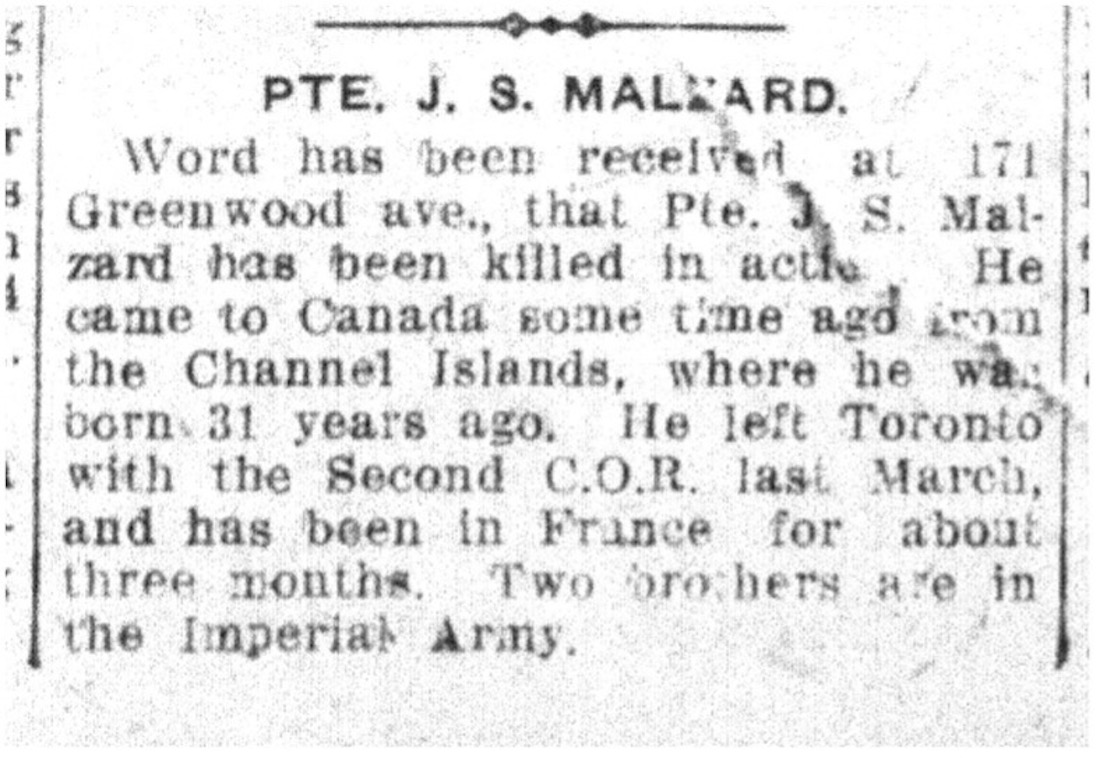

Private John Stanley Malzard, Regimental No. 3032675

John Stanley Malzard was born to John and Rachel Malzard on Jersey, Channel Island, England, on 25 February 1887. He was single and working as a truck driver in Toronto when he was conscripted under the Military Service Act, 1917. Private Malzard was enrolled on 9 January 1918 at Exhibition Camp in Toronto. He presumably underwent basic training until 25 March 1918, when he departed for England. Arriving on 3 April, he proceeded directly to Camp Witley, where he presumably progressed to infantry training. The Battle of Amiens was consuming manpower and the increasing casualties necessitated his move to France; he arrived at a reinforcement camp on 17 August. Pte Malzaard was with the 19th Battalion by the 18th. He, along with old hands and the newest replacements. continued the hard pounding fight until finally, on 10 November, he found himself outside Hyon, where his records become sparse. We know he received “GSW Chest Penetration,” a gunshot wound that penetrated his chest. He was evacuated to 6 Canadian Field Ambulance, where he died that day of his wounds. John Malzard’s headstone includes an inscription from his family: “Lo, the pain of life is past / all his warfare now is o’er.” Private John Stanley Malzard is buried in Mons British Cemetery.

Private Gilbert Shewfelt, Regimental No. 3132565

Gilbert Shewfelt was born in Kincardine, Bruce County, Ontario, on 20 June 1887 to Peter and Elizabeth Shewfelt. He worked as a farmer, presumably on the family farm, and was single when he received his conscription notice under the Military Service Act, 1917. Gilbert proceeded to London, where he was sworn in on 2 April 1918. Private Shewfelt was initially assigned to the 47th Battalion, but once in France he was reassigned to the 19th Battalion while in a reinforcement camp. He arrived within the 19th forward echelons on 12 September 1918 and was just in time to participate in the 19th’s relief of the 28th Battalion near Cagincourt, France. During the relief in line, he and the rest of the 19th were greeted by the Germans with an intense artillery barrage that caused numerous casualties. Gilbert remained safe despite the German artillery fire. We know little more of Private Shewfelt’s life at the front until 10 November, when his service records reveal that he was killed in action. Unfortunately, no Circumstances of Death form is available, nor is there an image of his headstone. Many of the records for names beyond those starting with “S” no longer exist, so we can only assume he was killed in action, along with his comrades of the 19th, outside Hyon. Gilbert’s father, Peter, died in 1925 and his mother, Elizabeth, lived to 85, dying in 1945. Private Gilbert Shewfelt is buried in Mons British Cemetery, Belgium.

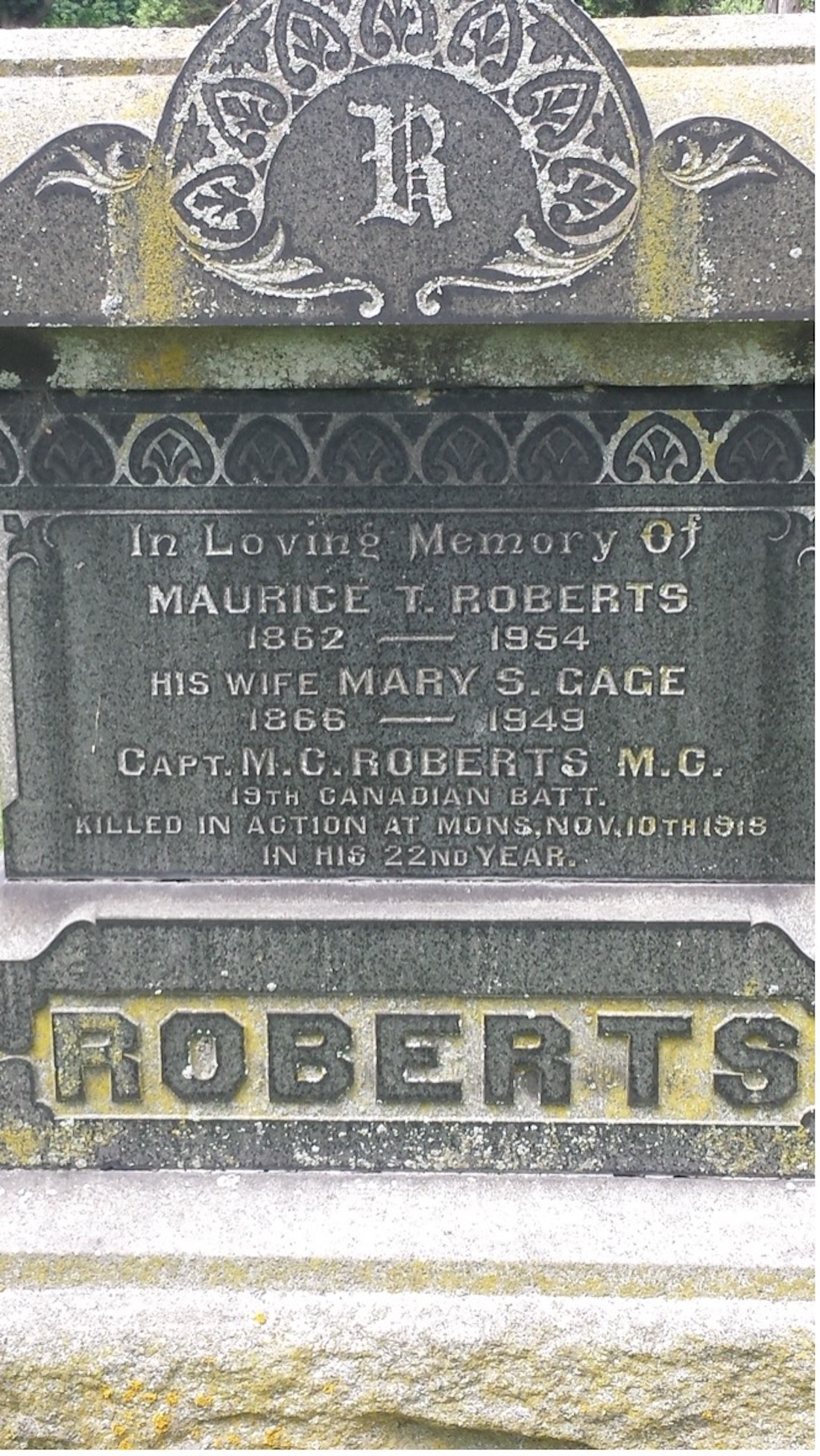

Captain Maurice Cameron Roberts, MC

Maurice Cameron Roberts was born on 19 August 1897 in Hamilton, Ontario, to Maurice and Mary Roberts. His enrolment documents note service for one year with the Hamilton Collegiate Cadets, three months with the 91st Canadian Highlanders, and that he was currently serving in the 12th York Rangers. His transfer to the 12th York Rangers from the 91st CH was probably due to his attending school as a “Law Student,” likely at Osgoode Hall, Toronto.

He enrolled on 5 January 1916 in Hamilton with the 120th Battalion. Once in the UK, the 120th was broken up for reinforcements and he was transferred to the 19th Battalion. Lt Roberts was treated for conjunctivitis in June 1918 but quickly returned to duty with the 19th. During the battle of the Canal du Nord, 26 July 1918, Cameron Roberts was decorated. His citation reads:

“Awarded the Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry & devotion to duty. When the unit on his right was driven back, this officer counterattacked, bombing along 150 yards and establishing a block in the trench. Then after organizing a support platoon in-case he was driven out, he sent back a report on the situation. Later with 5 men, he went on down the trench, and gained another 50 yards, bombing out an enemy party. Throughout the day his work was splendid.”

Capt Roberts was wounded on 27 July, with a gunshot wound to his left thumb from a machine gun bullet. He was hospitalized for a few months, returning to duty on 21 September 1918 with “no disability.”

Capt Roberts continued through the fighting until he was killed in action 10 November 1918 at Hyon. The circumstances of his death are: “Killed in Action. Whilst proceeding across a strip of ground which was swept by machine gun fire, to the Company holding the right flank, to obtain necessary information, he was hit in the legs by machine gun bullets and died soon after.” His family included the inscription “Faithful unto Death” on his headstone. He is buried at Frameries, Communal Cemetery, Belgium.

Lieutenant Cecil Ewart Gladstone Robertson

Cecil Robertson was born on 17 February 1884. His enrolment documents state that he was born in Essendon, Australia, whereas his birth was registered in Pickering, England, to Donald and Emma Robertson. Cecil was single and employed as a steward in Toronto when he decided to join up as a private, regimental number 55094. He was formally enrolled on 8 November 1914 and immediately assigned to the 19th Battalion. He and the rest of the 19th sailed on the SS Scandinavia in May 1915.

Cecil was hospitalized for two days with influenza in April 1916 with No. 4 Canadian Field Ambulance. He was recognized for his leadership potential on 26 January 1918 and was promoted to Temporary Lieutenant; he subsequently attended officer training. Back with the 19th, on 10 August 1918 he received a gun-shot wound to the chest during the second day of the Battle of Amiens. It appears to have been relatively minor, entering and exiting the flesh with no deeper penetration and no complications in his recovery. He returned to duty with the 19th Battalion on 29 August. Cecil Robertson had joined in the early days of the war as one of the original 19th Battalion recruits and had survived the war all the way through to 10 November 1918, the final action at Hyon.

The circumstances of his death report reads: “Killed in Action: While taking part in the attack on the town of Hyon, he was hit in the stomach by enemy machine gun bullets and instantly killed.” Lt Cecil Robertson is buried in Frameries Cemetery, Belgium.

Lieutenant William Wilfrid Copeland

William Copeland was born on 7 August 1891 at Collingwood, Ontario, to William and Mary Copeland. His enrolment documents list him as single and employed as an electrician prior to joining the army. William enrolled at Windsor, Ontario, on 1 December 1915 into the 99th Battalion. While with the 99th Battalion, he was quickly promoted from private to company sergeant major before the 99th was sent overseas. His meteoric rise was presumably because he exhibited obvious and much-needed leadership traits for a newly formed battalion of inexperienced infantry. As soon as the 99th arrived in England, he was unfortunately reverted to sergeant, and then five months later he reverted to private once again. There is no indication of disciplinary action as the cause for the reversions in rank, but the 99th was disbanded and the personnel were absorbed into the 35th Reserve battalion as a reinforcement depot, likely necessitating the reversions. William was transferred to the 19th Battalion on 4 October 1916. Perhaps his leadership potential previously identified in the 99th Battalion was recognized in the 19th; he was soon sent to England for officer training, May 1917.

While in England, William Copeland was admitted to Grove Military Hospital, London, on 1 August 1918 and diagnosed with “gonorrheal arthritis.” The physician’s report notes: ”On admission condition below par, is thin and anaemic looking. Joints somewhat stiff.” The medical form included a section asking, “Is it attributable to, or aggravated by, the officer’s own negligence or misconduct?” The typed-in response was, “Yes, V.D.G. [venereal disease gonorrhea].” Further comments indicated, “This officer has improved since coming here, but is still somewhat debilitated. Complains of slight pains in joints especially in damp weather but not of an acute nature. No discharge from urethra now. This officer requires hardening.” The physician’s notes also record that William had been hospitalized for VDG in 1916 as well. Treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (STD) prior to the advent of antibiotics was very lengthy and likely very unpleasant for the patient. The expectations of officers as exhibiting the highest moral standards is incorporated into the medical form as a “yes/no” question. The attending physician was seemingly unimpressed with the expressed ailments of Lt Copeland and his perceived lack of moral standards, and thus included the recommendation for Lt Copeland to “harden” himself. The Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) was tasked with the treatment of injuries and diseases in order to conserve manpower and sustain the supply of healthy soldiers to the frontline. Those soldiers with venereal diseases were considered to have caused a self-inflicted disease or injury as per the directives of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), which took precedence. The VD rates in the Canadian Corps were one of the highest in the conflict, with 15.8% of servicemen being diagnosed with some form of STD. Lt Copeland was recommended to return to “Command Depot after which he should be fit for service.” Despite the editorializing by the medical staff at Grove Military Hospital and the prevailing British Army perspective on STDs, the CAMC took a more scientific approach to the study of STDs and created special hospitals in England for study and treatment. (Source: Lyndsay Rosenthal, “Venus in the Trenches: The Treatment of Venereal Disease in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919.” PhD dissertation, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2018.) Dr. Robert Fraser, Regimental Historian, has concluded “…VD was [therefore] a medical issue, not a moral failing.”

It appears that Lt Copeland finally returned to the 19th Battalion, 2 October, 1918, during the 2nd Division’s relief of the 4th Division and parts of the 1st and 3rd Divisions on the outskirts of Blecourt. Copeland would soon participate in hard fighting at the Battle of Cambrai and Rieux-en-Cambresis and onwards to the final action at Hyon. Outside Hyon he received a severe gunshot wound that penetrated his chest causing extensive damage. William Copeland clung on to life in successive military hospitals in France until he finally died of his wounds, 23 December, 1918, at No. 20 General Hospital, Camiers, France. Lt William W. Copeland is buried at Etaples Military Cemetery, Pas-de-Calais, France. His family included the inscription on his tombstone, “He endured as seeing him who is invisible”. The Copeland family also included a memorial to William on the family monument in Collingwood, Ontario.

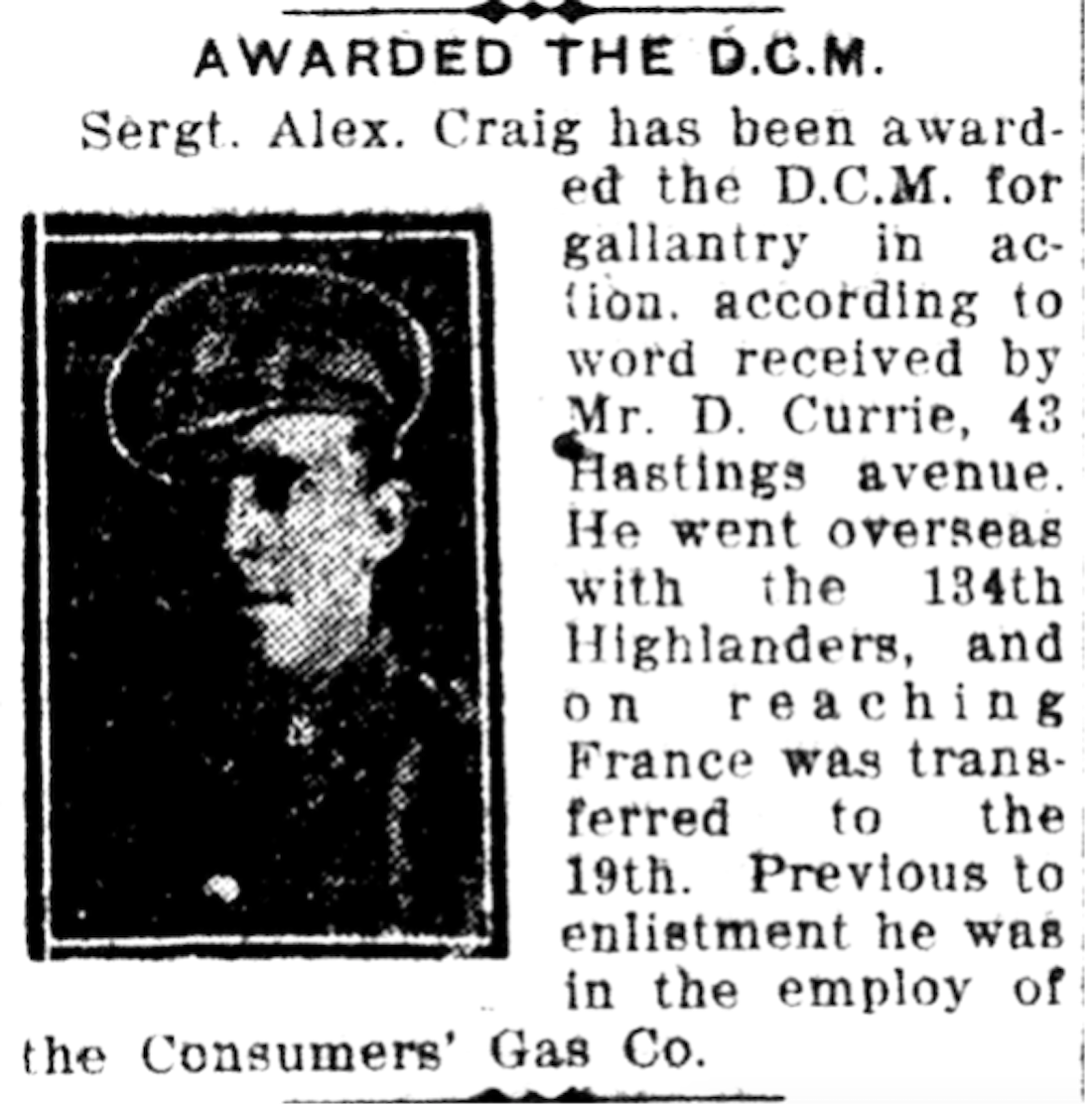

Sergeant Alexander Craig, DCM, Regimental Number 799377

Alexander (Alex) Craig was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on 21 February, 1891. No information is available about his family or when he came to Canada, other than he had a brother William Craig, his official next-of-kin, who also lived in Toronto. Alex was single and employed as a “Gasmaker” according to his enrolment documents. Alex enrolled in Toronto, on 18 January 1918, into the 134th Battalion but was transferred to the 19th Battalion shortly thereafter, likely because the 134th was destined to be broken up for reinforcements. He would have received his basic training at Exhibition Camp in Toronto and was shipped overseas in August. Craig arrived in Liverpool on 19 August and was immediately moved to Camp Witley reinforcement centre, where he likely received more training for the next ten months in preparation to be sent to the front. Craig was finally transferred to the 19th Battalion at the front, 12 June 1917. The 19th happened to be in reserve in order to rest, train, and incorporate the newest replacements after their numerous casualties at Fresnoy. From June to September 1918, he received promotions to Corporal and Sergeant. He would gain extensive combat experience in the coming battles of Hill 70, Passchendaele, Marcelcave, and Rieux-en-Cambresis.

During October 1918, he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, the second highest decoration next to the Victoria Cross. His citation reads: “799377 A/Sjt A. Craig Infy. This NCO under intense fire dashed forward and charged an enemy machine gun post single handed. He shot the No.1 of the gun, and turned it on the rest causing them severe casualties. This personal act of courage contributed largely to the success of the attack.” (London Gazette, 31011, published 14 January 1919).

Sgt Craig continued to fight and survive through to the attack on Hyon. On 10 November 1918, he received a “gunshot wound head perforating.” He lingered for a few days but succumbed to the traumatic head wound at 3:30 AM on the 14th at 4 Canadian Casualty Station. Sgt Craig is buried at Valenciennes Communal Cemetery.

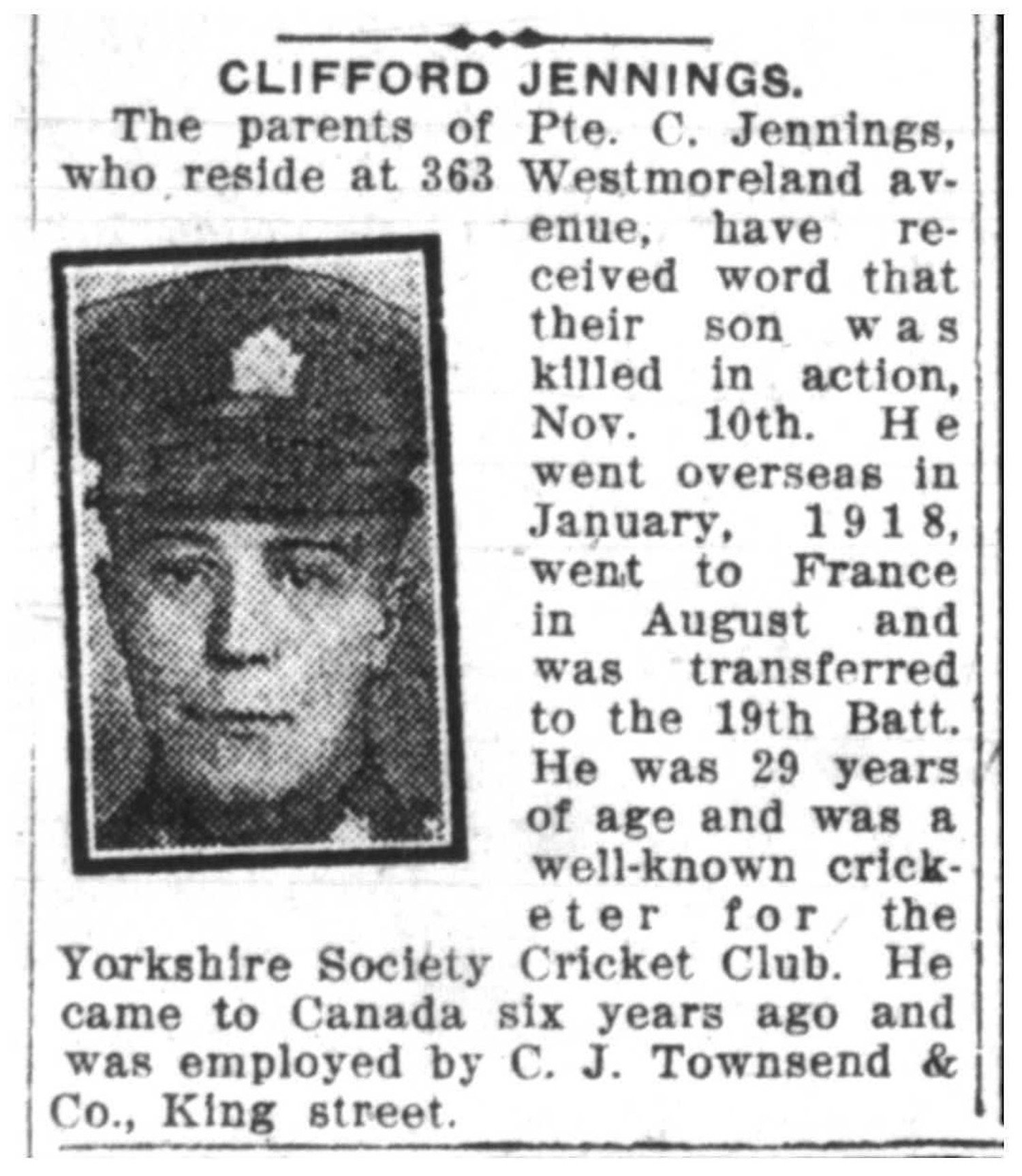

Private Clifford Jennings, Regimental No. 3032328

Clifford Jennings was born on 5 September 1889 at Shipley, Yorkshire, England, to Joseph and Annie Jennings. He was single and employed as a “Finisher,” according to his enrolment documents. Clifford lived with his parents in Toronto and was conscripted under the Military Service Act in January 1918. His enrolment medical noted he was relatively small in size, standing 5 feet, 1 inch. It was also noted he had bad teeth and was underweight.

Pte Clifford quickly left Canada on 13 February and arrived in England on 26 February, transiting directly to Camp Witley, likely for significantly more training. By August, he was transferred to the Canadian Corps Reinforcement Camp in France. He then was transferred to the 19th Battalion, arriving 15 September 1918. He would have joined the 19th just days before the action at Rieux-en-Cambresis and the later battle of Cambrai. From there, with the Germans in retreat and the Allies in pursuit, the 19th steadily moved towards their final action at Hyon.

The records for many soldiers conscripted late in the war were often brief in nature or sometimes missing altogether. The latter is the case with Pte Jennings in that his service records have just the barest of information needed, and the circumstances of death form is missing completely. His personnel file includes the phrase “Killed in Action,” but that is all we know of Pte Clifford Jennings’s final battle. Perhaps he was killed by artillery shrapnel or, like so many other soldiers from the 19th Battalion on the 10th of November, cut down by the German machine gun troops outside Hyon. We will never know. Pte Clifford Jennings is buried at Mons British Cemetery with the following inscription from his family on his headstone: “Gone but not forgotten.” The obituary (see image at right) appeared following the notification of his death.

Private Walter Curry, Regimental No. 2537338

Walter Curry was born on 1 March 1893 in Augmacloy, County Tyrone, Ireland, to George and Mary Curry. Walter was single and employed as a truck driver in Toronto when he volunteered to join the 10th Regiment, Royal Grenadiers on 7 June 1917. Walter stated on his enrolment documents that he had two years previous service with the Canadian Army Medical Corps, 10th Field Ambulance. Pte Curry remained in Canada for training until February 1918, and then sailed overseas to England, arriving on 3 March 1918. Walter remained in training at Camp Witley until 9 October 1918, when he was transferred to the 19th Battalion in France. He would have joined the 19th during the pursuit of the Germans through to Mons.

Walter Curry was barely with the 19th Battalion one month when he found himself outside Hyon, Belgium. Perhaps because of his previous service with the CAMC, “[a]bout 11:00 AM on November 10th, 1918, he went forward to bandage a wounded man, and he was later found by his company, lying dead with a machine gun bullet in the side.” Pte Walter Curry is buried at Frameries Cemetery, Belgium.

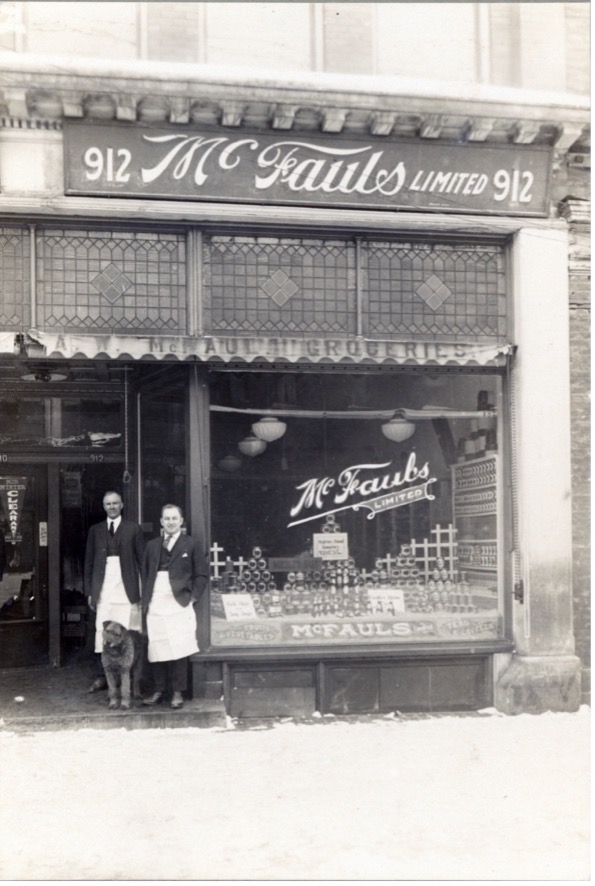

An exterior view of the family grocery store, McFaul’s Limited, at 921 2nd Avenue East, Owen Sound. The man on the left is Clarence’s father, A. W. McFaul, alongside Robert Cecil, Clarence’s younger brother, who served with the 1st Canadian Tank Battalion. Photo from the collection of the Grey Roots Museum & Archives, included in “They Served for Us”: Gillian Wagenaar, “Servicemen and Women: Wesley Clarence McFaul.”

An exterior view of the family grocery store, McFaul’s Limited, at 921 2nd Avenue East, Owen Sound. The man on the left is Clarence’s father, A. W. McFaul, alongside Robert Cecil, Clarence’s younger brother, who served with the 1st Canadian Tank Battalion. Photo from the collection of the Grey Roots Museum & Archives, included in “They Served for Us”: Gillian Wagenaar, “Servicemen and Women: Wesley Clarence McFaul.”

Gravestone for Lt W.C. McFaul, Mons Communal Cemetery Extension, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

Gravestone for Lt W.C. McFaul, Mons Communal Cemetery Extension, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

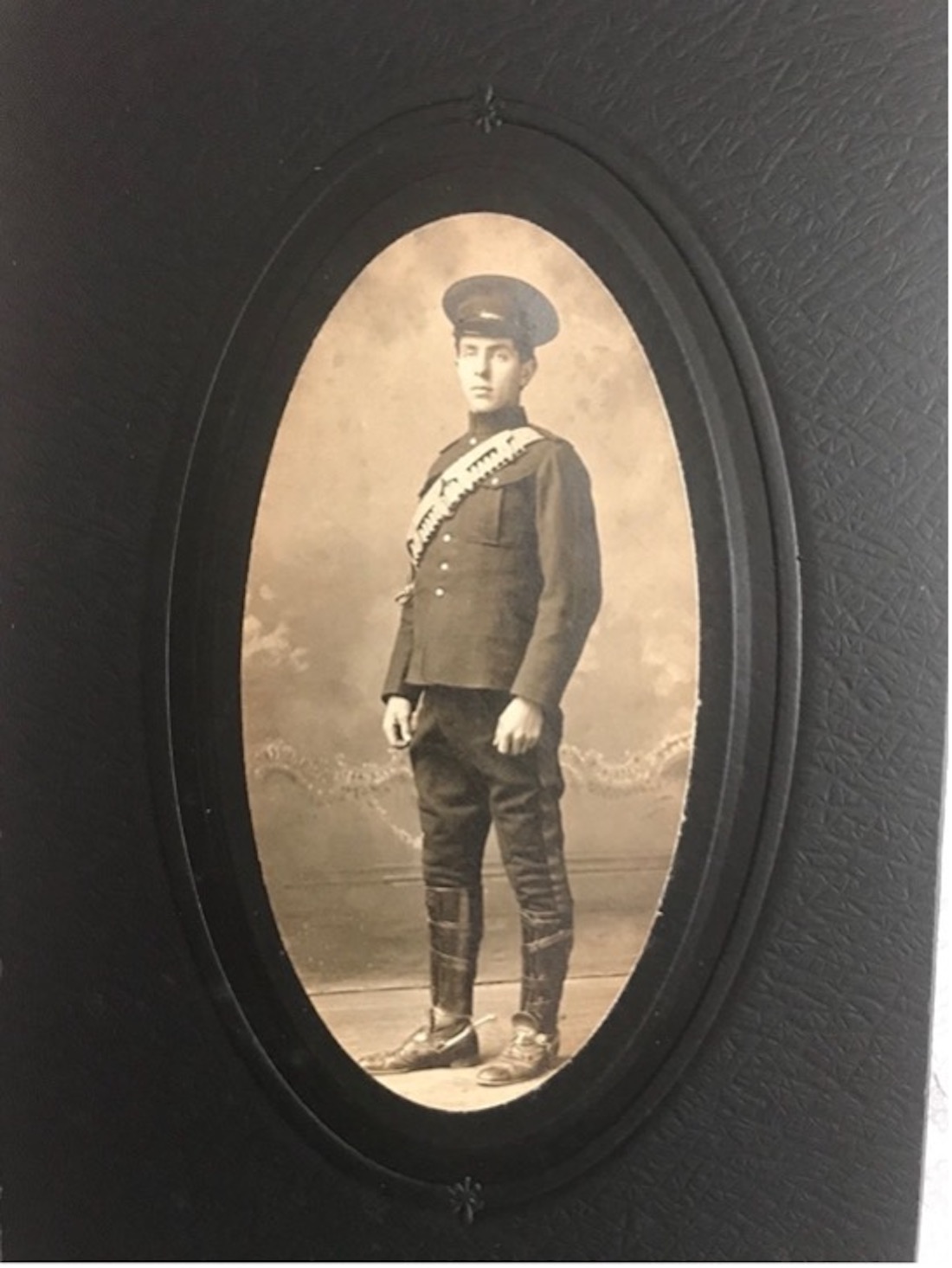

A photo identified to be that of Cpl Simon, likely taken before the war when he served in the “Canadian Militia for three years.” Source: findagrave.com.

A photo identified to be that of Cpl Simon, likely taken before the war when he served in the “Canadian Militia for three years.” Source: findagrave.com.

Gravestone of Cpl J.A. Simon. The family has included the inscription “Gone but not forgotten, Ida and son Russell.” Cpl Simon is buried at Mons Communal Cemetery Extension, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

Gravestone of Cpl J.A. Simon. The family has included the inscription “Gone but not forgotten, Ida and son Russell.” Cpl Simon is buried at Mons Communal Cemetery Extension, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

Pte Cronin’s gravestone, Mons British Cemetery, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

Pte Cronin’s gravestone, Mons British Cemetery, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

Pte Hales’s gravestone, Mons British Cemetery, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

Pte Hales’s gravestone, Mons British Cemetery, Belgium. Source: findagrave.com.

Pte Malzard’s obituary. Source: findagrave.com.

Pte Malzard’s obituary. Source: findagrave.com.

Headstone of Lt C.E.G. Robertson, Frameries Communal Cemetery. Source: findagrave.com.

Headstone of Lt C.E.G. Robertson, Frameries Communal Cemetery. Source: findagrave.com.

Obituary for Pte Jennings. Source: findagrave.com.

Obituary for Pte Jennings. Source: findagrave.com.