Introduction

The fighting on the 29th of October was bloody, the situation dire, and circumstances were complicated. The previous day the tanks of the South Alberta Regiment and the soldiers of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment entered Bergen op Zoom. The Argylls soon embussed and travelled west and then north by the main road into the town, where at about noon they were greeted by “cheering civilians waving orange flags.” They stopped at a park and ate lunch. Aside from the “occasional rattle of small arms fire” in the distance, “a real holiday atmosphere reigned.” The sky was blue and cloudless, and the sun shone down “benevolently.” “One would have thought,” Maj Hugh Maclean later wrote, “the war miles away.” Then, “the magic word ‘O Group’ struck apprehension into all hearts and shattered our blissful dream.”

As it turned out, the Lincs were held up “by a strongly posted enemy across a ditch running east and west just north of the town.” There was a causeway across it, albeit a badly cratered one with a “huge concrete cylinder placed across the road.” Brigade tasked the Argylls to cross the ditch and establish a bridgehead. They were told that “it could be easily crossed on foot, as it was shallow and narrow.” Whether anyone believed it at the time is another story.

“a real tempest of mortaring”

C Coy took up a position on the Allied side of the ditch to provide a firm base and fire support. D Coy would cross and occupy the houses on the other side, at which point A and then B would follow. Enemy fire awakened at C’s first movement: 88 mm airbursts followed by “a real tempest of mortaring. Heavy stuff it was, mostly.” C was in position by 1445 hours; D tried to cross as enemy “fire grew in fury.” It soon became apparent that a daylight frontal assault was “out of the question.” C and D came under “heavy” 88 mm and mortar fire, “which kept up steadily for the next 36 hours causing many casualties.”

An attempt by the Carrier Platoon to find a route flanking the ditch proved “abortive” as did the attempt of one of D’s platoons to cross the causeway. At 0200 on the 29th, B Coy under Maj Armstrong moved up to the ditch, which proved to be a canal full of water. A and B Coys once again tried to negotiate the narrow neck of land on the left while D “would attempt in whatever manner to get across the causeway and establish positions in the houses on the far side.

“a murderous gauntlet”

A and B got across and moved eastwards towards the causeway, where they encountered grenades and small arms fire. C provided covering fire, and the companies reached the causeway at about 0500 hours and some of D reached the houses on the right side of the street by 0800 hours. Now, A and B had “to run a murderous gauntlet.” With Sgt Dewell of D supporting A and B, the “arduous business of house-clearing was next on the programme.” By 1630, the three companies had advanced sufficiently to allow the engineers to begin removing the concrete cylinder. The “close range state of battle … had now been won. But death by no means stayed its hand.” C Coy and the Carrier Platoon were “subjected to torrents of shelling, which became so bad that wounded men refused to leave their slit trench to be carried to the dressing station.” Soon enough, battalion headquarters also came under heavy fire.

There was “no great change” through the evening and the companies held their positions. Capts Mac Smith and Bill Whiteside, “with great coolness and imperturbability, organized food and ammunition parties and personally took them across the causeway … Under the circumstances, this was a wonderfully brave act.”

On the morning of the 30th, “their task accomplished,” the Argylls re-entered Bergen op Zoom for “a brief rest.” Maj Maclean wrote: “The cost of the action, won after victory seemed beyond the Battalion’s reach, was very great.” When A, B and D returned to the town on the 30th, their total strength of all ranks was 125, hardly more than one normal company. Although it had not crossed the canal, C Company had taken worse punishment than any other. Death found Argylls everywhere, whether in BHQ or the rifle companies.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Craftsman Albert Hayton Hunt (1921–44), 1st Bn Argylls

KIA 29 October 1944

“good combatant qualities”

After VE Day, Maj Hugh Maclean wrote a history of the Argylls’ war; a gifted writer, he had been with the unit since mobilization. After the battalion moved into winter quarters in early November 1944, he recognized the “brave men” and the “many who had given their lives” and whom “none would forget.” He named but a few; the last was “Bert Hunt the mechanic.”

“Father [was an] old soldier”

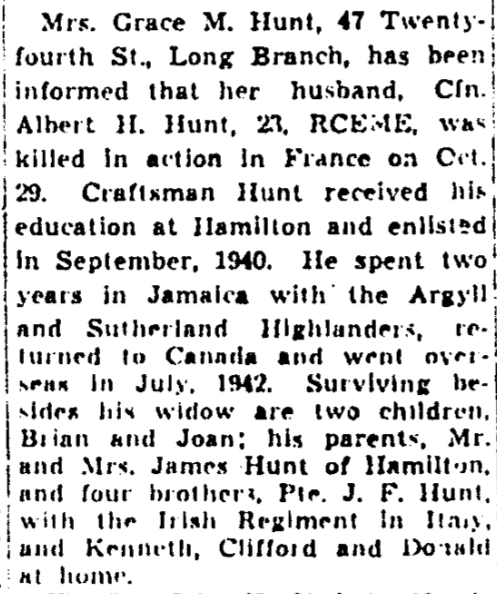

Hunt was born on his family’s hog farm on Hamilton Mountain on 4 June 1921. James Hunt and Winnifred Margaret Hunt had married in England in 1917. Bert liked hunting, fishing, wrestling, baseball, and hockey. After completing grade 8, he started working at 14; from 1938 to 1940, he was a plasterer’s apprentice for J.A. Brown, a building contractor. Having farmed “all my life,” he “hope[d] to operate my own farm” after the war. He enlisted on 25 August 1940 in Toronto for two reasons: first, his “Father [was an] old soldier”; and, secondly, “Duty.” His younger brother, James Frederick Hunt (1923-1997), served with the Irish Regiment of Canada. Bert Hunt transferred to the Argylls on 23 Sepember. He married Grace M. Googe (1923–1980) on 3 May 1941 at St Mary’s Anglican Church in Long Branch; they had a son, Brian Albert, the following February.

Pte Hunt quickly gravitated to the Transport Platoon (commanded by Maclean), qualifying as a driver mechanic. Hunt was 5’, 8¼”, 148 lb, with brown eyes and dark brown hair. In May 1943, a personnel officer assessed Hunt: “stability seems to be sound; deportment good; gives good direct answers. Is keen about his present employment and has good combatant qualities.”

“Likes present work as motor mech … Good attitude”

When the Argylls returned from Jamaica in May 1943, he had four days’ furlough with his wife and child, and then went overseas; they had a second child, Joan Margaret, in February 1944, a child he would never see. That same month, an officer described him: “Good appearance, cooperative, friendly manner. Looks healthy and of good stamina, makes no complaint … Likes present work as motor mech … Appears stable and well employed. Good attitude.”

After taking the flame-throwing course for carriers in July 1944, he went from private to craftsman; he received heavy vehicle accreditation in September. When the Argylls attacked Bergen op Zoom, Belgium, on 29 October, the enemy’s response was furious: “heavy 88-millimetre and mortar fire, which kept up steadily for the next 36 hours … [caused] many casualties [56].” At various times, all of the rifle companies, part of Support Company, and even battalion headquarters endured.

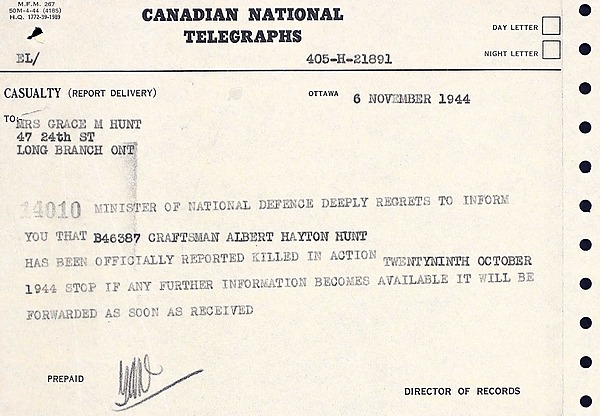

There is no record of when or where Bert Hunt died, but Craftsman Hunt was one of the dead and the astute Maclean, his long-time officer, paid tribute to his memory as one of those “none would forget.” Grace Hunt, “a housewife” living with their children in Long Branch, received the life-shattering telegram about her husband’s death on 6 Nov. 1944. Hunt left his parents, his children, and three younger brothers (Kenneth Edward, Clifford, and Donald), and a few effects: a pen, two watches, a lighter, “Letters & Photos,” and a religious medal.

By 1946, Grace Hunt had moved to his family’s farm in Mount Hope; some time later, she married his brother, a veteran.

I honour your sacrifice, Cfn Hunt – David Sweet, MP

Note: Pte Hunt’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

LCpl John Neill Marshall Jr (1917–44), 1st Bn Argylls

KIA 29 October 1944

“I am now 73 … and unable to go to his grave … I know he is only one of the thousands that lay there but the memory remains”

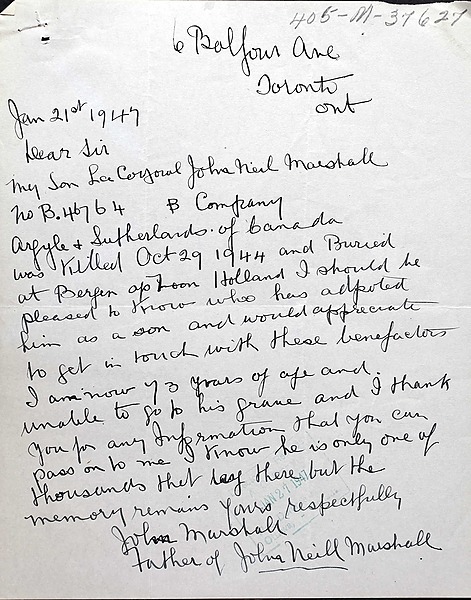

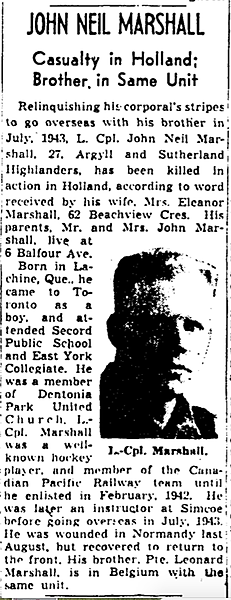

John Marshall Sr wrote a letter (21 Jan. 1947, see image) to the government to enquire, unsuccessfully, what Dutch family “had adopted him as a son.” Born in Lachine, Que., on 30 March 1917 of an “English” father and an “Irish” mother, John’s family moved to Toronto when he was “a boy.” Educated at East York Collegiate, he attended Dentonia Park United Church. A “well-known hockey player and member of the Canadian Pacific Railway team,” he was an elevator operator and a printer.

Enlisting on 28 February 1942, Marshall had served in the RCE since September 1941. He was promoted LCpl on 3 Dec. 1942. At 5’, 5”, 142 lb, with fair complexion, hazel eyes, and brown hair, he had two minor and typical charges: AWOL and drunkenness. On 28 June 1943, “at [his] own request,” he reverted to private to join the Argylls and his brother Len, who was with them. Part of a close-knit group in D Coy, they missed a train at the end of leave and, as Pte Jake Leyland put it, they then “took off for [another] 14 days.” They were not alone in such capers in the build-up to D-Day. Battalion scuttlebutt had it that they would forfeit pay and not much more; for once, scuttlebutt proved true.

“Isn’t this great?”… “It wasn’t great for long”

Near Caen in late July 1944, as darkness fell, the “sky was lit up by flares.” Len commented to his brother, “Isn’t this great?” His post-war editorial comment was: “It wasn’t great for long.” On 5 Aug. 1944, C and D coys attacked Tilly. Wounded on the left cheek and discharged on the 17th, John returned to the unit.

Johnny Marshall survived Igoville and Hill 195 in late August; the early fighting in Belgium, especially at Moerbrugge; and the fighting that resumed on 15 October. In spite of some reinforcements in mid-September, the battalion was woefully under strength, and ravaged further by the ferocity of the fighting in the last days of October. For the most part, the weather was as dark as the undertakings and the undertakings were deadly.

“got one or two away before they got him”

He was killed at Bergen op Zoom on 29 October 1944. The sun shone “benevolently” that day. If the sun was benevolent for a change, nothing else was. That day D fought its way across a causeway over a “deep irrigation ditch” while under heavy fire. Two platoons moved into houses on either side of the main road. Under LSgt Tom Dewell, 17 (D Coy) occupied the ones on the right; Marshall and 18 were on the left and “we couldn’t get out.” Germans in a nearby dugout strafed them with machine guns. Pte John Warrilow remembered that Marshall, on the 2nd floor, “undertook to throw a grenade right into … the dugout and he got one or two away before they got him.” Dewell recollected “he got killed not staying away from the goddam window.”

“never forgot ‘Johnny’”

Marshall was one of 9 killed and 29 wounded that day; soon after, brother Len was evacuated with battle fatigue. John left behind his parents and wife Eleanor Marion; they had no children. Pte Ed Cane (B134186), a good friend (and also an Argyll after VE Day), from the Coxwell/Gerrard neighbourhood of Toronto never forgot “Johnny.” Ed’s son, Bruce, recalls that once he even “broke down sobbing.” His father’s remembrance “stuck with me,” Bruce said. “Clearly [Marshall] made an impact on my Dad.” “His reaction speaks eloquent volumes” about Marshall and it was “only him – very unusual.” For Johnny’s family and friends, his father had it right – “the memory remains.”

Between 21 and 29 October, 32 Argylls were killed in action and 98 were wounded.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

In respect – An Argyll

Note: LCpl Marshall’s poppy is located in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance: left cluster, middle grouping, second at far left. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

A view of the Zoom during the war. It was expected that the Argylls would walk across it easily.

Site of the anti-tank ditch (2009).

Another view of the site of the anti-tank ditch (2009).

Dragon teeth section of ditch, Bergen op Zoom (2009).

The one bridge left intact over the Zoom, blocked by this concrete barrier.

Telegram to Grace M. Hunt informing her of the death of her husband, Cfn Bert Hunt.

Obituary (Globe), Cfn Hunt

Letter from John Neill Marshall Sr regarding his son, dated 21 Jan. 1947. “I am now 73 … and unable to go to his grave … I know he is only one of the thousands that lay there but the memory remains.”

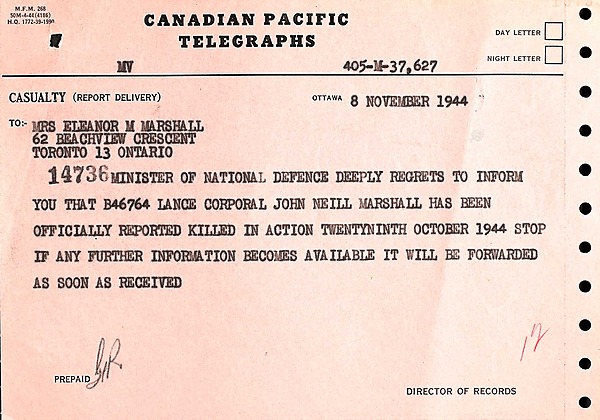

Telegram to Eleanor M. Marshall informing her of the death of her husband, LCpl John Neill Marshall Jr.

Obituary, LCpl Marshall