Introduction

The project to write Argyll poppy texts remembering the Argyll Fallen in 1944 and 1945 has preoccupied me over 2019 and 2020. Many of them come to mind from the time spent on Black yesterdays. Alex Laba caught my attention again last year. Capt Sam Chapman’s comment about him in a letter home to his wife was etched in my memory. Moreover, Pte Laba died during, by comparison to what came before, a peaceful period. He was the last Argyll to die in 1944, and Cpl Harry Ruch’s observant diary entry about the dirtiness and the stickiness of small actions came again to my mind.

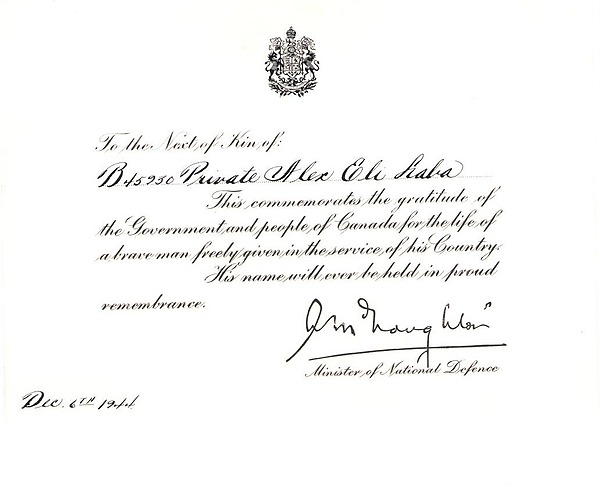

As with the other Argyll KIAs, I tried to find his family. Here, my first impulse was a Canada 411 search (for folks still with land lines) for “Laba” and “Grimsby” and there was “A. Laba.” I called immediately and – as soon as I mentioned “Argyll” – I had a warm response from Alex Laba, Pte Laba’s nephew, who was named in honour of his fallen uncle. Alex has been enthusiastically supportive; he enlisted the aid of other members of the extended Laba family and put together a package of images, letters, postcards, and artefacts. I have met with Alex several times now, and I extend my thanks to him and the Laba family. He provided additional photographs for scanning (before the COVID-related shutdown). In due course, I shall have them scanned and they will be added to this poppy text.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“I hear that quite a few boy[s] went overseas. I guess that I’m just one of the unlucky ones but still hoping.”

– Pte Alex Laba

The winter of 1944 was a hard one, marked by extreme cold and a record-breaking blizzard in southern Ontario. For the Laba family of Grimsby – Wasyl (1890–1967) and Annie and their children – there was an added dimension to the winter’s bleakness: they learned of their son’s death in battle in the Netherlands.

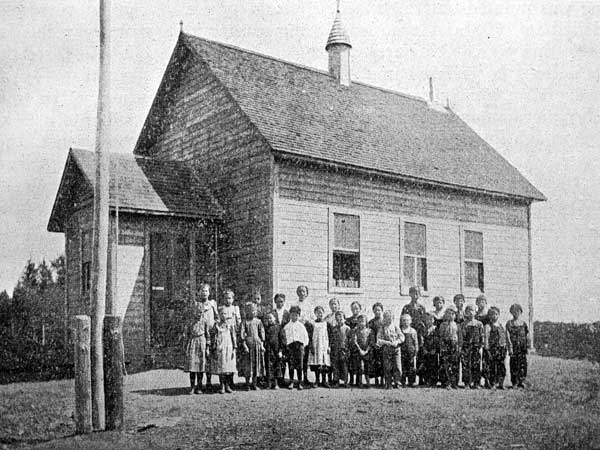

“from Galicia, a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to Manitoba”

The Laba family’s odyssey over the past 46 years had been long and characterized by societal disruption. Matty Laba (1845–1928) emigrated in 1898 from Galicia, a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to Manitoba in search of economic opportunity and better times. The opening of the Canadian west by the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier coincided with upheaval in Galicia that resulted in the massive immigration of Galicians in the 1890s. The Labas, along with their compatriots, settled in the Mountain Road area of Neepawa amid a Ukrainian Catholic community. Wasyl Laba married Annie Kostenchuk on 24 January 1915 and settled down on Mountain Road, where their children attended the rural school and church. Their religion, their language, and their culture provided the touchstones of life there.

“summers working on a fruit farm near Grimsby”

Alex Eli Laba was born on 14 March 1923, his parents’ fifth child. He commenced schooling at age 8, completing grade 7 in schools in Mountain Road (a rural one) and Grimsby before leaving at age 15. Wasyl and Annie moved their family to the Niagara region in 1933/34 at the height of the Great Depression, presumably in search of better opportunity. His younger brother, Roy, had died in Mountain Road on 6 March 1933, at 9 months. On one of his military forms from July 1940, Alex wrote that he had lived ten years in Manitoba and seven years in Ontario. Before enlistment, he spent two summers working on a fruit farm near Grimsby and then two years as a weaver at the Merritt Brothers Basket Factory in Grimsby, where his weekly wage was $12.50. Merritts made no provision for Alex’s job after the war, and his stated preferences were work in a steel mill or gold mine.

“the two languages spoken at home were English and Ukrainian”

Pte Laba’s personnel file notes that the “racial origin” of both parents was Ukrainian and that the two languages spoken at home were English and Ukrainian; his religion was “Greek Catholic.” The Niagara region from St Catharines to Grimsby had a small Ukrainian Catholic community; in Grimsby, they built a church in 1935. Wasyl Laba worked in the basket factory, which provided, according to his grandson Alex, “always a supply of wood.” Wasyl “fell off the roof [while] building the church [and afterwards his] demeanour changed; he became withdrawn and quiet.” Annie Laba was “a happy person, loved family, loved to cook, loved the family.” They all spoke Ukrainian but the “family wanted children to speak English.” They were “quite a religious family [who attended] mass every Sunday.” For the most part, the second generation married within the Ukrainian Catholic community.

“adventure”

When the Argylls mobilized on 21 June 1940, a number of Grimsby lads such as Joe Carleton (KIA 5 August 1944), Tommy Page (KIA 9 August 1944), Murray Ryan (KIA 18 August 1944), Glenn Lewis “Joe” Bearss (KIA 27 August 1944), and Mike Forrester enlisted. Young Alex signed up on 10 July 1940 (B45930); the unit took its first private soldier on strength on the 24th and gave him the first number – B45500. Almost four years later, Alex gave “adventure” as his reason for joining the army. In 1940 he was 5’, 8¾”, 138 lb (and still growing), with blue eyes and blond hair.

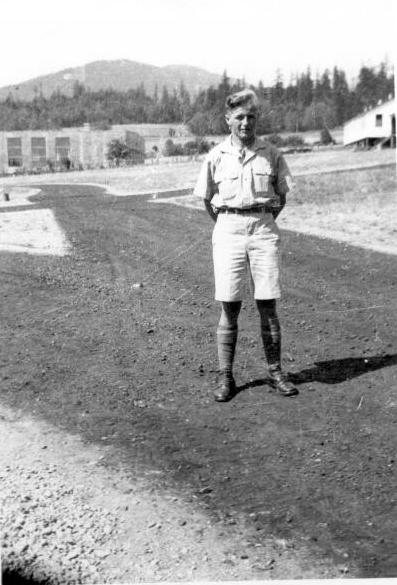

“old kilts – old anything at all – old uniforms”

The adjustment to military life took time. The battalion “were using old kilts – old anything at all – old uniforms … Ross rifles … It really was,” as Lt Don Coons remembered, “just a bunch of old junk that was kicking around.” The first two months were spent in Hamilton before moving to Niagara Camp and later Chippewa Barracks. By the end of September 1940, the nominal roll included 34 officers and 839 other ranks. In time, they received new uniforms and new weapons. In May 1941 they entrained for Nanaimo, B.C., where they underwent route marches, training courses, “hardening exercises,” and work on military administration. By 20 August, they were back in Standard Barracks in Hamilton, where they had a last leave before entraining for Quebec; there they boarded the RMS Drake for a tour in Jamaica that would last 22 months.

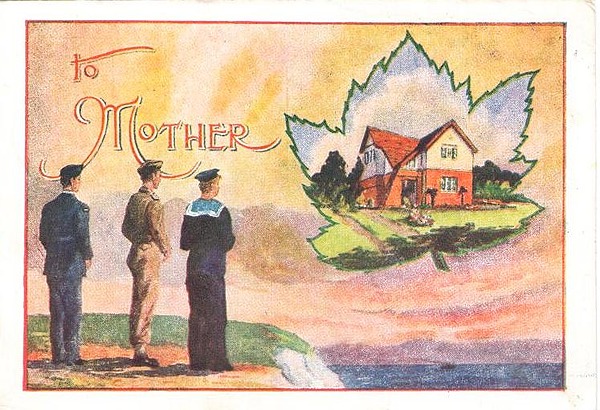

The sojourn in the sun entailed guard duty at the prisoner of war camp at Up Park Camp, Kingston, alternating with training in the mountains at Newcastle. LCol Ian Sinclair, a decorated veteran of the First World War, saw to it that training was rigorous and intensive: drills, small arms, specialized courses, and more new equipment. There was also malaria and dengue fever. Pte Laba was in C Coy. On 17 April 1942, he sent his mother a postcard to “wish you a very happy mother’s day. I received your easter card two days ago. I am feeling fine and hope you all are still better. Your son, Alex.” [It was signed by the officer censoring mail for C Coy, Capt. R.A. Paterson.]

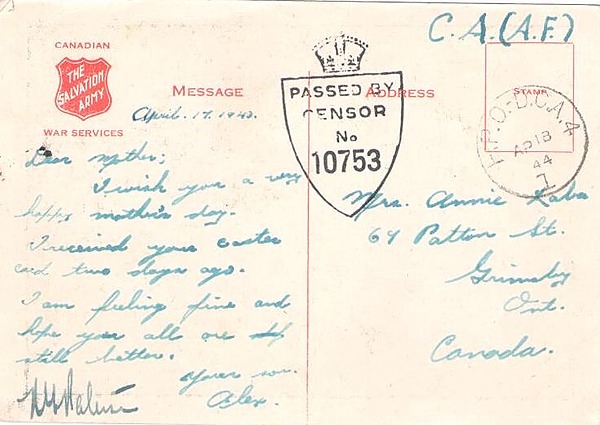

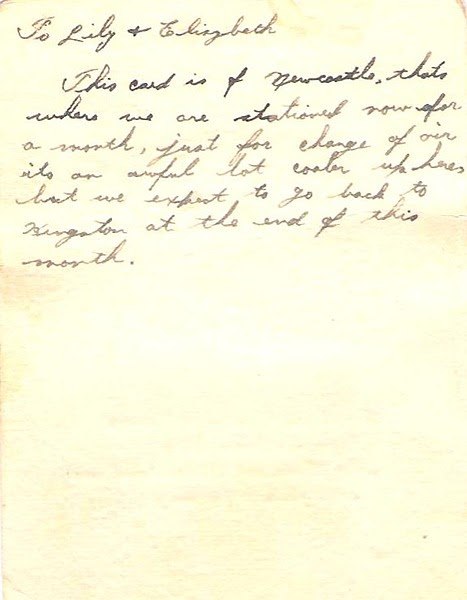

Alex sent a seasonal card to his sisters Lily and Elizabeth:

“This card is of Newcastle, that[‘]s where we are stationed now for a month, just for change of air it[‘]s an awful lot cooler up here but we expect to go back to Kingston at the end of this month.”

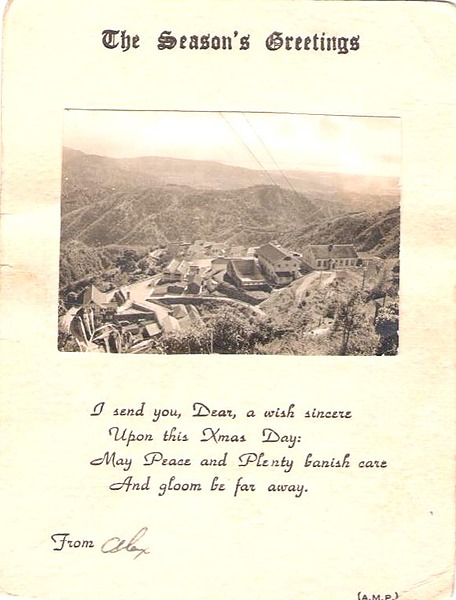

The card’s message read:

I send you, Dear, a wish sincere

Upon this Xmas Day:

May Peace and Plenty banish care

And gloom be far away.

“I hear that quite a few boy[s] went overseas … I’m just one of the unlucky ones but still hoping”

On 18 January 1943 Alex wrote to his parents:

Sorry, that I didn’t write sooner but I was in the hospital for twenty one days with malaria. I went in on the twenty second of Dec. So I didn’t enjoy Xmas or New Years end[?] much. The first two weeks I was in a pretty bad shape and the third I was just a little weak. I got one week sick leave when I got out and I am going on parade in a couple of days. I feel fine now and there’s not a thing wrong with me. J & I received Mary Yukalchuk’s parcel on the 21st Dec and yours on the twenty eight[h]. There isn’t much to write about except that it [is] a little cooler now but not for long and i really miss the snow. There’s no news about us coming back, but we might be back this summer I hope. I hear that quite a few boy[s] went overseas. I guess that I’m just one of the unlucky ones but still hoping.

Have you heard from Mary [his older sister] yet ’cause I haven’t had a letter from her for almost a year now. I wrote her one just before xmas and sent her a picture of myself but I haven’t heard from her yet.

Well I guess that[’s] all for now. So long and thanks a million for the parcel and the Xmas card. Oh yes I wish you wouldn’t send me any cigarettes in a parcel cause twenty packages for five dollars is away too much if you can get a thousand for ___[?] half that.

Well good luck – and please answer soon. Alex.

“A smiling, friendly soldier”

The Ukrainian Catholic community of Grimsby gave many of its sons to wartime service, including Alex’s brother George. Alex had enlisted for “adventure” and he hoped to go overseas. By 26 May 1943, the Argylls were back at Niagara Camp and “the ordeal of medicals, ‘M’ tests, interviews with psychiatrists, finger-printing, photographing and … parades.” The unit lost a lot of men owing to age and/or medical condition, including cadres of officers and NCOs plus 129 other ranks. They took on strength new officers and 152 other ranks. After his interview by a Personnel Selection Board (PSB) officer at Camp Niagara on 31 May 1943 at Camp Niagara, the army examiner found Alex:

A smiling, friendly soldier of above-average build. He is in excellent health; weight 160 lbs, and is 5’, 10” tall. Is in A Category. He was co-operative during the interview. Has a likeable attitude and has indications of Sound Stability.

Skating, baseball and a little swimming are his sports, shows and reading are his Pastimes. Hunting is his hobby. Born in Manitoba of Ukrainian parents, he has 4 brothers and 5 sisters. He came to Ontario aged 11, his home now in Grimsby.

At present he is #2 Bren Gunner, but thinks he would rather be a rifleman.

“Infantry (Bren Gunner) – Suitable for Overseas Service”

The examiner recommended him for “Infantry (Bren Gunner) – Suitable for Overseas Service.”

Pte Laba finally got his wish; he was going overseas with the 1st Battalion. There were disembarkation leaves and furloughs before entraining for the east coast on 9 July; Alex Laba almost certainly spent his leave with his family in Grimsby; it would be the last time they saw him.

“well adjusted to army” – Personnel Selection Board officer

In the United Kingdom, training intensified at all levels and the unit acquired its legendary commanding officer, LCol Dave Stewart. A PSB officer interviewed Pte Laba again on 15 January 1944. He considered Laba’s deportment “soldierly”; his disposition “self-confident”; his grooming “neat”; and his physical appearance “good.” Overall, he evaluated him as “Reserved, well adjusted to army – slightly below average mental alertness.” The last comment related directly to Laba’s “D” score on the “M” test, which comprised a series of eight sub-tests: picture association (3); mechanical aptitude (2); arithmetic (1); vocabulary (1); and word relationship (1). Alex did better on the two mechanical tests and best on the word relationship. His military record was almost spotless: no crimes, no major or minor offences, and only two fines: one on 11 October 1941 (14 days’ deduction of pay for “Wilful defiance of Auth”) and the other on 18 September 1943 (he forfeited seven days’ pay for an infraction under Army Act 11 for refusing to obey an order). He trained on the Bren gun and the PIAT (an infantry anti-tank weapon) in 1944 and participated in the various divisional exercises; the misery of being in the field in cold, wet weather; the various inspections by visiting dignitaries such as LGen Bernard Montgomery, King George VI, and others; and the anticipation of the forthcoming invasion of Europe.

“Coy losses are getting heavy” – CSM George Mitchell, C Coy

The Argylls landed in France in July 1944 and suffered their first casualties on the 25th. Throughout August 1944, C Coy saw bitter, almost continuous fighting and experienced battle’s terrible face – death. CSM George Mitchell of C Coy wrote in his diary: “Caen smashed – leaves one with hopeless feeling – utter destruction.” Most Argylls were stunned by “the destruction and the stench.” At Bourguébus on 2 August, Mitchell noted, “Shelling still terrific – difficult to move.” The days were warm and dry; the nights were spent in slit trenches and there was little water. On 5 August, C and D Coys assaulted Tilly-La-Campagne. The “attack was received by intense enemy shell, mortar, and small arms fire” and the Argylls absorbed their first day of substantial casualties: 24 KIA, 17 wounded, and 1 POW. As Pte Bill Wolosyn, 14 Platoon, C Coy, remembered: “14 Platoon was slaughtered.”

“street fighting – house clearing”

Back in Bourguébus on the 6th, Mitchell commented yet again that “shelling still terrific…. Our Gang … never far from Trench. Rations a headache.” Returning to Caen on the 8th, C Coy had “Good meal – shower – shave etc.” Mitchell felt “like new man”; the feeling would not last. The next day C Coy took Haut-Mesnil, which was “a scattering of buildings about a huge quarry”; it involved, as Mitchell put it, “street fighting – house clearing.” There were 9 killed and 14 wounded. Late on the 10th, the Argylls undertook Dave Stewart’s brilliant night-time infiltration of Hill 195 with C and D Coys “forward.” They took the hitherto unassailable point, engaged in hand-to-hand fighting when they landed in German trenches, and braced for the inevitable counterattack the next day: 7 KIA, 24 wounded. Mitchell wrote: “Surprise move – right on through Enemy Lines to Hill 195…. We are completely surrounded – shelling heavy.” The battalion moved back into a rest area but it did not last long.

“Terrifying”

On the 15th, Mitchell wrote: “enemy resistance terrific … feel pretty low … Coy losses are getting heavy … Dysentery common in Coy … Battle of the Falaise Gap is on.” By the 19th, B and C Coys “were engaged in very heavy but most successful fighting” at St-Lambert. For C Coy, the night “move” through St-Lambert was, even for Mitchell, “terrifying.” On 22 August, LCol Stewart amalgamated B and C Coys because of their losses and “no reinforcements.” The unit’s attack on Igoville on the 27th had “B and C Coys leading.” Again, it was a gory day for the battalion: 14 KIA, 46 wounded, and 16 POWs! Pte Alex Laba was among the day’s casualties.

Soldiers became battle-hardened (and battle-weary) quickly. When Alex suffered his wound, the unit had been in action for barely a month. What a month! 71 KIA, 220 wounded, and 17 POWs for a total of 308; at full strength, the four rifle companies numbered about 500 altogether!

For the time, Pte Laba’s war entered an interlude. He was hospitalized the next day; on 3 September, they sent him to No. 24 Canadian General Hospital in the United Kingdom for further treatment and recuperation. Discharged on the 20th, Laba was back in NW Europe on 17 November and attached, again, to the Argylls on 20 November 1944. His file is not entirely clear on the dates because one form has him qualifying on the 2” mortar as well as the Bren on 14 November (it was signed by Lt Norm Perkins, 15 Platoon, C Coy). Whatever the story, after a brief leave in October, Alex was back with the Argylls and C Coy by the end of November.

“another one of those heart breaking affairs from next-of-kin” – Capt Sam Chapman, C Coy

When he returned, the whole battalion was in a rest area at Stokhoek, Netherlands. It was rest in name only. Argylls were wakened “by the cheery playing of the Argyll Pipe Band.” There was time for church services, “personal clean-ups,” letter writing, and movies. The unit took over a former German rifle range and proceeded with its training program without further delay.” LCol Stewart instituted a “School of Instruction for NCOS” to give new NCOs “a firmer theoretical basis for the practical work lying ahead.” There were also wet canteens, sports programs, dances (with “130 fair Dutch maidens” at one), concerts, and training, “which at a later date might mean the difference between life and death.” Stewart aimed “to instil a new ‘esprit de corps’” and “once again make the Argylls into a hard-hitting, efficient fighting team.” On the 4th, the battalion learned it would move that day back to Drunen and “by nightfall” the unit was back in place on the Maas River.

“a small German patrol crossed the Maas” – War Diary, 5 December 1944

Lt Claude Bissell’s daily entry in the unit’s war diary started with an account of that eventful patrol:

At 0200 … a small German patrol crossed the Maas, but was soon discovered by one of our patrols, who killed two of the prowlers with accurate small arms fire, while the rest escaped. Unfortunately, the enemy had taken the precaution of removing paybooks and other forms of identification, which prevented us from obtaining any information from the bodies.

“very sticky and dirty”

Cpl Harry Ruch later characterized “the brief skirmishes with small enemy parties, rearguards and patrols” as “very sticky and dirty.” They resulted in casualties and Pte Alex Laba, recently returned to C Coy, was the only casualty for the Argylls that night. Capt Sam Chapman, 2ic of C Coy, later recalled it in a letter to his wife:

“This was a lad [Laba] who’d been wounded [on 27 August at Igoville] + came back and was killed in a clash with a Jerry patrol that came in on us in Doevren (near Heusden) on 4th [sic] December. That’s one night I’ll remember.”

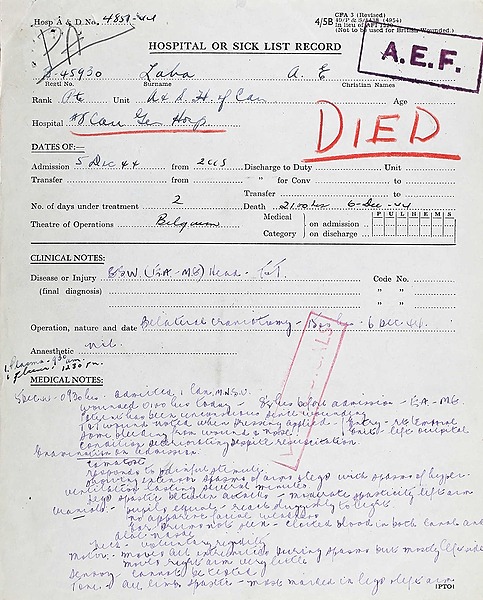

“he should be given the benefits of any chance” – Capt Norman C. Delarue, surgeon

There are three pages of medical notes concerning Pte Laba’s treatment. According to this record, he was wounded at 0100 hours on 5 December by a German machine gun. The wound was “perforatory (skull) Thru & thru.” Capt Doug Bryce, the new Regimental Medical Officer, examined him in the Regimental Aid Post at 0315. Laba was “unconscious” with a pulse rate of 84 and a respiratory rate of 26: “Entrance rt. Temp, exit left.” By 0500, they moved him to the 15th Canadian Field Ambulance: “Condn only fair. Dressing reinforced. Is bleeding also from nose.” Alex’s pulse rate had dropped to 57, the respiratory rate was 36, “reg; somewhat stertorous.” At 0900 hours they transferred him to No. 8 Canadian General Hospital and the care of Capt Norman Charles Delarue. Laba remained “unconscious.” There was “some bleeding from wound + nose condition deteriorating despite resuscitation.” Pte Laba, he noted, “responds to painful stimulation.” There were “extensive spasms of arms + legs with spasms of hyper-ventilation lasting several minutes.” He “reacts druggishly to light.” Delarue concluded: “No essential change occurred in this man’s condition apart from intermittent spasms of hyperventilation and extensive rigidity and it was decided he should be given the benefits of any chance that operation offered him.” Accordingly, Capt Delarue operated “at 1500 hours 6 Decr without anaesthesia.” He cleared the wounds of bone chips and found “no definite evidence of ventricular penetration.”

“DIED”

Alex’s “condition slightly improved during Operation but during the immediate P.O. period B.P. fell despite transfusion and pulse and respiration became irregular.” Despite the treatment and the chance, Pte Laba died at 2100 hours on 6 December after two days of treatment. The surgeon ordered a post-mortem “examination of head re extent of central damage and involvement of ventricular.” A surgeon performed the autopsy at 1000 hours on the 7th: “T&T [through and through] G.S.W. Head and Brain.” At the top of the medical chart, someone scrawled in large block letters: “DIED.” Pte Alex Laba’s “adventure” was over; he was 22.

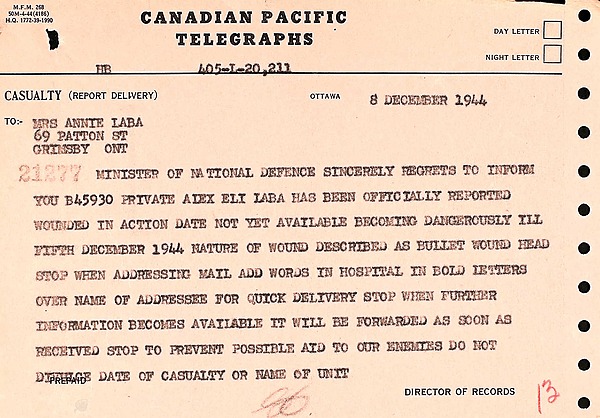

In his Christmas card of 1942 to his sisters, Pte Laba had expressed the poetic hope that care would be banished and gloom far away. It would not be the case for the Christmas of 1944. On 8 December, Annie Laba received the dreaded telegram informing her that her son had been wounded; she received another the following day with its life-shattering pronouncement that Alex had died of his wounds.

The Hamilton Spectator reported Alex’s death on 11 December 1944; he had been “dangerously ill with a bullet wound in his head,” dying the next day. The obituary noted that he “had only been back in the lines a few days when killed.”

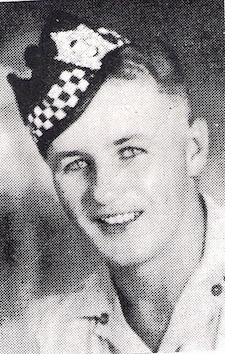

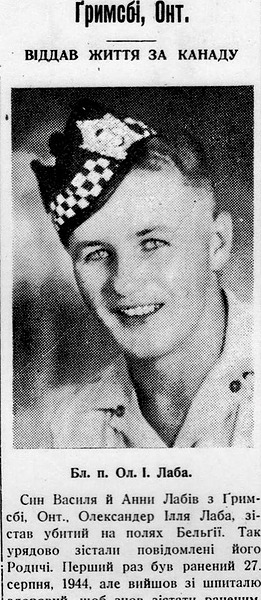

“God grant that the blood and sacrifice of … so many young Ukrainian men does not go to waste”

The reaction in Grimsby was immediate. A requiem service was held at St Mary’s Church on the 10th, followed the next day by a “mass for the repose of his soul.” The Laba family provided an obituary for their community in Ukrainian. Titled “Sacrificed His Life for Canada,” it includes a picture of young Alex wearing his Argyll Glengarry at a jaunty angle. “Alexander grew up in Grimsby and went to school there, that is where is large family is, and is one of the most knowledgeable in the Dormition of the Blessed Mother Ukrainian Catholic Church. Panachyda [prayer service] for the repose of Alexander’s soul by Rev Father Superior Nichola Kohut and Rev Father E. Lesiuk who spoke a wonderful homily.” There was more: “God grant that the blood and sacrifice of the lives of so many young Ukrainian men does not go to waste but will in the end bring our Ukrainian people freedom.” It seems that the Laba family supported the Ukrainian National Committee, which espoused the ideal of an independent Ukrainian republic.

On 30 January 1945, Capt Sam Chapman wrote to his wife: “I had a letter … another one of those heart breaking affairs from next-of-kin.” Clearly, Chapman had written to Annie Laba about her son: “His sister wrote back and apologized for having to write because her mother couldn’t read English.” “Sometimes I wonder,” the acerbic Chapman opined, “just who is fighting for what. The ones that have the most seem least inclined to defend it.” Forty-two years later, Chapman wrote about the “man who falls in battle … He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank. There is an end but no conclusion.”

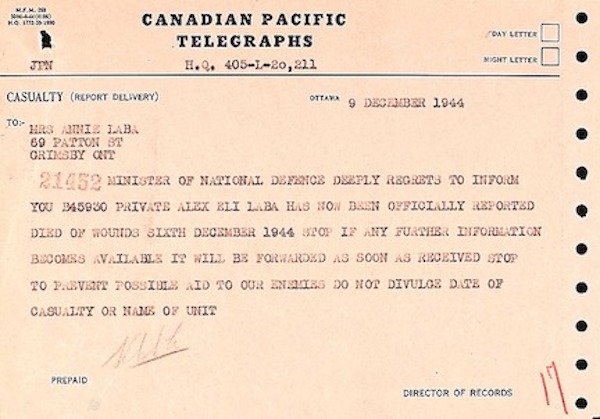

Alex Laba left everything to his mother: “Personal Papers & Cards,” a “Small snapshot album,” his Glengarry (he wore a Balmoral or helmet in the field) and an Argyll cap badge, a $50 victory loan, a few souvenir items, a prayer book, a rosary, a New Testament, and a few personal items such as a broken watch and a broken cigarette holder. In due course, she would receive notice and images of his gravestone, his effects, and his medals, including the Silver (or Meritorious) Cross for her. The medals were never mounted and remain in their boxes to this day.

“I think he was a brave man; he fought for his country” – Alex John Laba

The family remembered. John Laba had “medical problems” that prevented his enlistment. John’s son, born on 31 July 1945, was named after his fallen brother. Alex John Laba “lived right beside my grandmother.” There were “cousins and relatives within blocks; I was surrounded by family all the time, a close family.” The family, however, “never talked about him.” Alex found out when he was older, “talking to my aunts … It was funny, they never talked [about his uncle], but the battalion picture [of the Argylls] of 1940 hung in the hallway of their house.” He was “killed in the war and that was it.” Alex Laba became “more interested later.” “Consciousness,” he suggests, “comes much later in life since reunions and we talk.”

“People now realize if you don’t have anything written down, it will just disappear.” When his grandparents’ house was cleared out, he found many of his uncle’s things. He showed “stuff to cousins, brothers and sisters.” At that point, his uncle’s life “fell into place.” “I think he was a brave man; he fought for his country and he will not disappear.”

Between 4 November and 6 December 1944, 1 Argyll was killed in action and 8 wounded.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Remembered respectfully – An Argyll

Note: Pte Laba’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Mountain Road School, Manitoba.

Old and new Mountain Road schools and St Mary’s Ukrainian Catholic Church.

Merritt Brothers Basket Factory, Grimsby circa 1930.

In Nanaimo, B.C.

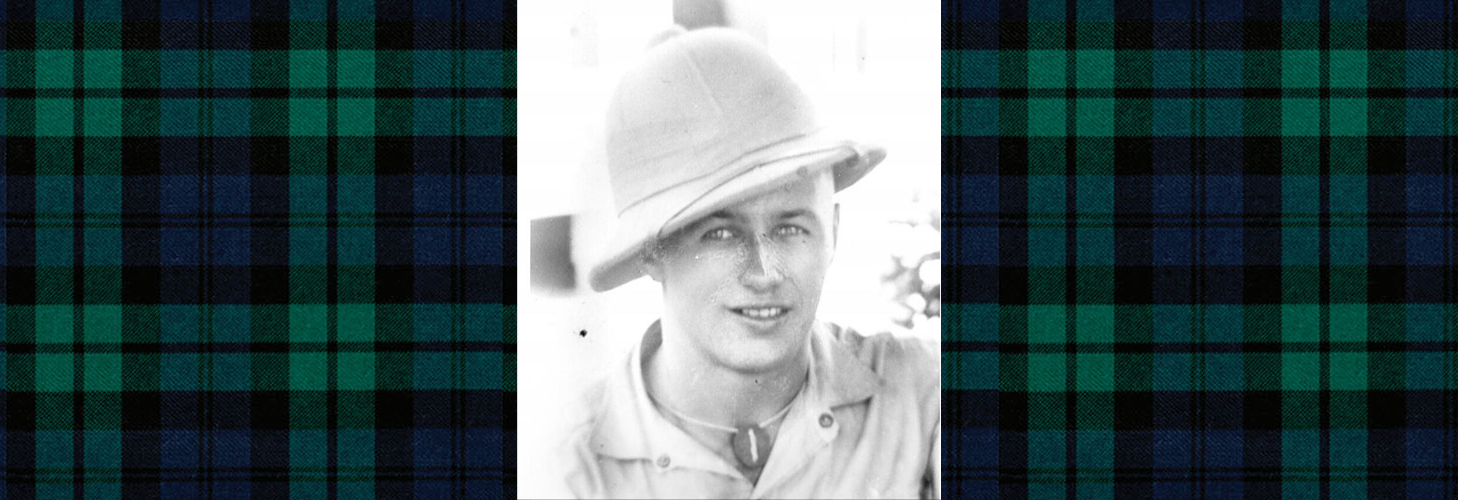

Alex Laba in Jamaica wearing a pith helmet.

Alex Laba on the right.

Pte Laba in uniform.

Postcard (front and back) sent to his mother.

Greeting card (front and back) sent to his sisters.

Pte Alex Laba’s hospital record.

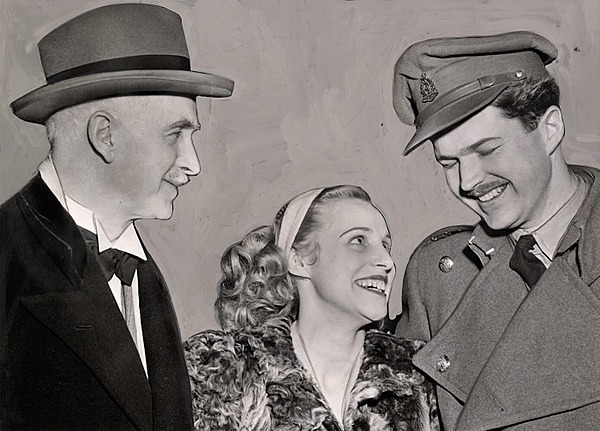

Capt Douglas Bryce, MO, Argylls, who first examined Laba at the Regimental Aid Post. In this photo, Capt Bryce is being welcomed home by his father and wife. After the war, Dr Bryce (1917–2008) became a renowned otolaryngologist and surgeon at the University of Toronto.

Dr Norman Charles Delarue, who operated on Laba, is pictured here in 1986. After the war, Dr Delarue (1915–93) became a renowned thoracic surgeon and one of the earliest crusaders against smoking.

Obituary, Hamilton Spectator.

Former St Mary’s Domitian Ukrainian Catholic Church, Grimsby.

Interior, former St Mary’s Ukrainian Catholic Church, Grimsby.

Part of obituary, Ukrainian newspaper.

Pte Laba’s gravestone, Schoonselhof Cemetery, Antwerp, Belgium.

Pte Alex Laba’s Glengarry and badge.