Introduction

After the action at Watervliet on 15 Oct. 1944, the Battalion left for “its new concentration area north-east of Antwerp. We found quarters in a Hospital for Crippled Children that provided the hitherto unknown luxuries of running water and electric lights.” In the following days, LCol Dave Stewart sketched out 4th Division’s new plans in the drive for Antwerp. The “first general objective was Esschen [Essen],” and the Argylls anticipated “a mixed sort of opposition – the usual fierce, fanatical rearguards combined with pockets of weary Germans, anxious to surrender.” As for the ground, “flat, sandy, and heavily wooded,” it “lent itself well to mines and booby-traps” and was “ill-suited to armour.”

On the 17th, the battalion’s officers were all together for the first time in a while. LCol Stewart collected all of their liquor and they had a party. Capt Sam Chapman wrote to his wife: “It’s awfully silly actually but the responsibility is terrible + a little blow up probably saves nerves.” Within two weeks, three of those officers would be dead and seven wounded. The unit moved on the 18th and again on the 19th when LCol Stewart laid out the plan of attack at an O Group: “We were now poised for the push-off, which was to take place early on the 20th. At an “O”-Group in the evening, the C.O. issued the following orders:

Information about enemy: Along our centre line, a road running due north … were groups of enemy of varying strength, either in the woods on either side or in the buildings along the road. At least two 88mm’s were known to be in position covering obvious approaches.

Information about our own troops: 10 … Brigade will be on our right … We will move up the 4th. Brigade centre line, with the L.S.R.’s [sic] on our left. One squadron of tanks of the Grenadier Guards will be under command and aircraft of 84 Group will be at our disposal.

Intention: …to advance as far as possible along the centre line, clearing the enemy from the wooded areas on either side and from the built-up areas.

Method: Two companies up and two in reserve. “D” … supported by a troup [sic] of tanks, will be on the left of the centre line; “B” … also supported by … tanks, will be on the right … The carrier platoon, with the Scouts embussed, will provide right flank protection and will liaise with the nearest elements of 10 … Brigade. “A” and “C” … will remain behind with Main B.H.Q. and will be ready to move on being called forward by the C.O.”

War Diary. 20 October 1944 [C.T.B.]

The operation “Suitcase” began this morning. “B” … on the right found the going very tough from the moment they passed the start line (a cross-roads…). One of their tanks was disabled by a mine, and when the officer got out to investigate … he was shot and killed by a sniper. Since “B”-Company’s terrain was heavily wooded, we had great trouble in maintaining communications … The Carriers and the Scout Platoon on “B”-Company’s right flank had similar troubles and, because of heavy mortar and small arms fire, were unable to get forward.

“D” … in the meantime had made good progress against light opposition and were almost 1000 yds. in advance of “B.” … At 1325 they reported that they were waiting for “B” … to come abreast of them in order to co-ordinate the drive through Calmpthout [Kalmthout], the town that they were now approaching.

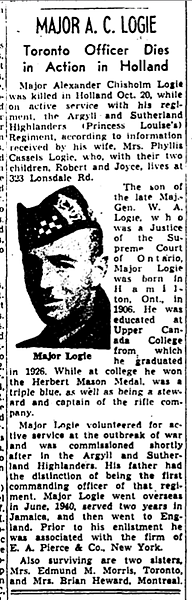

Eventually “B” … worked its way up and the process of clearing out the town began. During the afternoon the troops were under accurate mortar fire almost continuously and were harassed by snipers. At 1510 hours word was received that Major Logie had been killed by a sniper. Casualties for the day numbered approximately 30, including Lt. [Ed] Brooks [the Carrier Officer] and Capt. Blaker, who were both wounded. By night the companies had dug in and consolidated.

[KIA: A/Major Alexander C. Logie, A/L/Sgt Earl H. McAllister, Pte Theodore J. Gallant, Pte Albert L. Harris, and Pte Gordon H.E. Kitchen. Wounded: 19.]

Major R. A. Paterson

Decades after the war, Maj Bob “Flan” Paterson, C Coy, considered the fighting in late October among the toughest and bloodiest of the war for the Argylls. He thought LCol Stewart’s tactics were his best, better than Hill 195. Later, Stewart put Paterson forward for two separate Military Crosses for his leadership of C Coy during these harrowing days.

On this day, the Argylls and B Coy lost Maj Alex Logie, Paterson’s best friend, a man whose name was synonymous with the Regiment and an officer beloved by all. Paterson’s first-born son, Robert Alexander “Sandy” Paterson, was named, in part, after his friend. Logie’s children, Robin and Joy, have been wonderful in supporting the Regiment in remembrance of their father. The letters between their parents are a memorable part of Black yesterdays, and they happily shared them. At the book’s launch in 1996, there was a long line waiting for the author (one was always waiting for this author) to sign their copies. Both Joy and Robin were there, along with comrades of their father, who shared memories and gave voice to their lasting respect for him. Joy was in tears and Robin almost speechless.

Maj Hugh Maclean, author of the 1st Battalion’s history in 1945, had few peers with either words or perception. He was puzzled that he couldn’t “figure him out” or “never got close to” him. “Over the years,” he wrote, and after rereading the history (his own), “it suddenly occurred to me that what you had in Logie was the Spirit of Culloden and the Forty-Five. And he was really special and I didn’t get that for a long time, until after the war was over.”

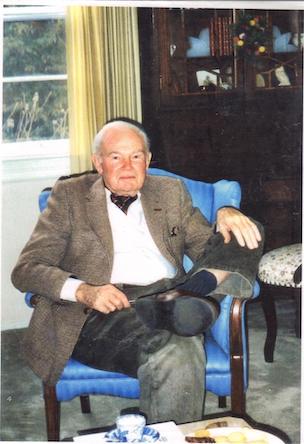

It was the 1980s and I recall vividly sitting with Maj Paterson in his living room overlooking one hole of the Brantford golf course (golf was one form of poetry for him). At one point, he pulled out one of his wartime scrapbooks. One page had a faded picture of temporary graves, including Logie’s. Paterson had drawn an arrow on the page to the grave and written, “Alex lies here.” He bowed his head and we sat together for a moment in silence and respect. There was something, I thought then, exquisitely good and gentle in Paterson’s choice of words. I have not, in the almost 35 years since, changed my mind.

Alex Logie was, truly, “really special,” as Hugh Maclean would have it.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Alex Logie was a natural fit for the Argylls, the son of Major-General William Alexander Logie (1866–1903), one of the Regiment’s founders and its first commanding officer. In some ways, he was a 91st Highlander (the Regiment was raised in 1903) before he was even born, in 1906, in Hamilton. He was educated locally and at Upper Canada College. Although the family had moved to Toronto when his father was appointed to the Ontario Supreme Court, the Argylls would remain the family’s Regiment. After the mobilization of the 1st Battalion in 1940, 2/Lt Logie was taken on strength almost immediately. Unlike many of his exalted rank, Logie was older, married (Phyllis Lash Cassels in 1930), and had two children (Robert, known as Robin; and Joyce, known as Joy).

“one of the best in terms of being a soldier”

Alex Logie took to active soldiering with relish, dedication, and his own style. The men of 18 Platoon, D Coy, which he commanded, remembered fondly his playing taps on his harmonica after a day spent patrolling the Welland Canal. At times, he checked the troops on guard duty by canoe: “We thought,” one said, “he was Hiawatha.” The Battalion’s movement from Niagara to Nanaimo to Jamaica brought further training for Logie, closer integration into the unit and the cadre of young officers, and adventures such as providing the guard, along with Lt Bob Paterson, on the Agapenor in March 1942. A senior lieutenant, there were times, remembered his good friend Lt Jack Harper, that Logie “felt that he wasn’t getting a fair shake. He was a senior … lieutenant … one of the best in terms of being a soldier.”

In March 1943, Lt Logie left Jamaica for courses in Canada and then a three-month tour “overseas.” He was over 35, a cut-off age for active service, and the Battalion would be returning soon to Canada. Logie wanted to get into the war and not be left behind; the Battalion conspired to get him overseas before it and, thus, ensure the fulfillment of his wishes. As expected, older officers and soldiers were left behind when the Battalion went to England in the summer of 1943. Now a captain, Logie continued to write frequently to his wife and children, to train hard, and to await what lay ahead in northwest Europe.

“left out of the battle … at first”

The Battalion moved into the theatre of operations, and Logie was second-in-command (2ic) of one of the four rifle companies. In the early days of fighting, the 2ics were left out of battle (LOB) to ensure continuity of leadership should the officer commanding (OC) be killed or wounded. As Capt Bob Paterson, 2ic of C Coy, remembered: “[Captains] Logie, Harper, Zavitz and myself … we were all left out of the battle … at first.” It was not for long. After the engagements of early August and B and C’s battle at St-Lambert (18–21 August), casualties had mounted. B Coy had lost two OCs (one wounded, the other killed), and C Coy had lost one (wounded). The losses were so heavy that on 22 August B and C companies were amalgamated into one unit under Captain Logie; the combined strength was less than 70! Finally, on 4 September, there were sufficient reinforcements to reinstate the four rifle companies; Alex Logie, now an acting major, had B; his best friend, Bob Paterson, had C.

“I am happier every day about this Coy”

For the remainder of his life, Logie had two major concerns: B Coy and his family. In the spare moments that the former allowed him, he took time for the latter. On 15 September, he wrote to his wife:

Here I am again stopped for a few moments so I thought I would take time by the forelock and write you a line or two, just to say I am fine and everything is going well. At the moment I am sitting in the living room of a house, with my carrier outside the window and the radio extension in here and am listening (against orders) to a concert from London which is grand for a change. I have been up all night and snatched a couple of hours sleep this morning. Things are pretty quiet at the moment except for the odd mortar bomb + shell coming over at random nothing to worry about though when you are in a house … Every thing is going well in the Company and I think the C.O. is quite pleased with the work of the 2i/c’s [sic] … I am happier every day about this Coy though the men for the most part are doing a grand job and I have two very good officers and one fair one and a very good sgt major [C. MacDonald] whom I picked myself from D Coy and who is my right hand man.

“I love you my own Lovely one”

Another brief lull on 20 September meant time for another letter to his beloved Phyllis:

Two lets from you today and one from Rob + Joy [Logie’s two children] with the snaps in it. God! You have no idea how wonderful it is to get them my Precious … Gosh! the snaps are grand Petty I just loved them but I wish you wouldn’t cut yourself out of any of them because even if you had a squint a mile long you would still be the most lovely thing on earth … Now Woofie Darling a wee word to you. This is your birthday and I have been thinking of you so much all morning and looking at your face and wishing I could be there. I love you my own Lovely one. Keep a stiff upper lip till Old Hub gets home again. God Bless you.

Ten days later, he wrote:

“God! I’ll be glad to get out for a while where I don’t have to worry about a damn thing …” On 2 October, he looked forward to a brief leave: “I think Bob [A/Major Paterson] and I will take a trip into the recreational city [Ghent] tomorrow if there is nothing doing. I hear you can get ice cream cones, cherry pie, see a show and if you are interested in these sort of things watch ‘the Madam’ parade her 10 lovely girls from one house of ill fame to another.”

“it’s a miserable business sometimes”

Although essential to emotional and physical health, these short leaves were only diversions from the reality of battle, and Logie confided to Phyllis that: “It’s a miserable business sometimes Dear Heart but nothing can be done and you just have to get hardened to it.” On 10 October, he took out another recce patrol; LCol Dave Stewart was not pleased: “I was out all day on a patrol and when the C.O. came in to see me tonight and I told him, he got mad as hell and said ‘This is an order, you will not take out any patrols in future.’ I guess he is right but I hate like hell having my subalterns do them all the time.” Dave Stewart thought that one of the greatest challenges of a CO was ensuring that leaders at all rank levels did their job, not someone else’s. He also understood the compassionate impulses that underlay such actions.

“this chap actually cares whether I survive or not …”

The life of an OC in battle was lonely. There was almost no contact with friends and fellow officers, and casualties were part of daily life. Logie personified a leadership style that was empathetic and humane. He cared for his men and worried about young subalterns on the always dangerous patrols. The late Lord Peter Blaker was one such officer and recalled vividly and poignantly Alex Logie’s manifest concern for his personal well-being:

I was surprised to find my company commander [Major Logie] so concerned for … not only my success, but my safety. That was the impression he gave. He cared whether I survived or not. That was a very big plus. So instead of getting what I perhaps … expected, which was sort of crisp instructions (I was going to do this … and off you go) … it was a careful briefing. His operation groups would be carefully considered, not hurried. I suppose they might have been hurried if it had been necessary … And he was obviously trying to sum me up, that you could see in his eyes. But the principal factor, the principal feature, which surprised me — and I remember being surprised at the time — was this chap actually cares whether I survive or not … A very powerful encouragement to us all … And what I say of Logie was also true of [Lt-Col] Stewart, so that leads me to think it was an Argyll characteristic.

October was a hard month for the Battalion, and Alex Logie’s letters evinced even greater longing for his wife and children. On the 13th, he penned a reverie that had him going home, to his home in Toronto, seeing his sleeping children, and finally embracing his wife again. It proved too much:

I won’t go on any more Dearest one. My imagination will run away with me, and I don’t want any censor reading this. Can you picture all that Pet? So many times I’ve thought about it. I wonder when it will really come true? Must go now Dearest. Have to be up again at midnight and its after nine now. Nighty-night Beloved. God Bless your adoring Sandy.

“a bath in a real bathroom”

On 17 October, the whole Battalion was together again and Logie welcomed it:

“We are together for the first time in months and I heard the pipe band playing at BHQ for the 1st time since I came across the channel and it sounds wonderful … I am going to have a bath in a real bathroom, again the first I have had since England.”

That night, the officers dined together and got drunk; actually, LCol Stewart ordered them to do so, and apparently no one disobeyed. It was but a brief respite from battle and its terrible handmaiden, casualties; by the 20th they were in action again. The Battalion was clearing the approaches to Bergen-op-Zoom and B Coy was in the thick of it and under heavy fire. News came back about 1510 that Logie had been killed by a sniper.

“our good Padre Maclean buried him in a little town”

The result was devastating: for B Coy, for the Battalion, for his close friends, and for his family. Bob Paterson, his best friend and OC C Coy, wrote to Phyllis Logie on 6 November:

If I could only talk to you, see you, and tell you about Al it would be so much better. All I can do is write words that will be heartbreaking to you, Rob, and Joy. Al was killed by a mortar. He died instantly, and our good Padre Maclean buried him in a little town, Capellenbosh, north of Antwerp. It is cruel that the death of the finest of men can be written in so few words. You have not seen much of Al in the past four years. Can I tell you about him?

It started back at Nanaimo, that is, our friendship, and that of Jack Harper and Jack Harstone. Trout fishing, swimming, golf, and sing songs in our rooms those glorious cool west coast nights. We became very close and remained so. Al always led, always showed us a happy way to put in our days off. And so we went to Jamaica, the four of us. He taught us to play tennis, to dive, and to find the deep enjoyment of the simple things. He also set as fine an example of a soldier as I have seen. We never lived up to it, but were better for the trying. The lovely months of sun and blue and green will always be full of thoughts of Al climbing a coconut tree, Al at Shaw Park, Al on the ranges and playing cricket, battling me at tennis, diving in the Garrison Pool. God how he became part of us and as Ulysses, “part of all he met.” When he went to England, and we were a bit silent, and took to long walks in the mountains. England — and Al fighting tooth and nail to get back to his Father’s Regiment. He won and we formed Our Junior Board of Strategy and we all became Captains and trained through the hellish English weather. I shall never forget Al bundled in pyjamas, long underwear, battle dress, denim, and gas cape, and still cold. He taught us to make bivouacs, to sleep dry, and so on. He led his men always, yes, ahead of his major … I can see him now erect as ever, waving a flank up, holding them back from our artillery barrage, always encouraging, always leading. We drove through the Falaise Gap of death, across the Seine, the Somme, we fought into Belgium and Crossed the Ghent Canal with more blood and fighting than ever before. Al and Jack and I led our companies all through this maelstrom … When the news came, I was dazed. Jack Harper and I linked arms across shoulders and could not speak. The Colonel [Dave Stewart] could say nothing. Al’s Company was heartbroken. Two days later Jack Harper broke down and is now in England suffering from overstrain. It was not overstrain, it was Al.

“Al was my ideal … God what a terrible thing for you”

The Colonel has left for England and an operation. Before going he said Al was outstanding. He could not have said less. Al was my ideal, and I do believe I have seen enough of soldiering to know. There never was anyone who was such a square shooter, who was more understanding, or more kind. God what a terrible thing for you. It is always the brave who go and the weak who live.

Al will never be far from you, nor from me. “At the going down of the sun. And in the morning we shall remember him.” If you have read Dickens, or Maurice Maeterlinck’s “The Blue Bird,” you will find my sentiments as I should like to express them. Both say that we cannot be dead if one is thought of and remembered. Al can never be far because he left so much behind, so much manliness, and friendship, humour, and keen enjoyment of life. He will always be an inspiration to me.

Phyl, I cannot say any more. It is too hard. Please ask anything and I shall do it. All Al’s kit will be sent.

May God Give you comfort.

Maj Alex Logie was not forgotten; his memory and his example live on still. Phyllis Logie remained a central figure in the Toronto branch of the Argyll Women’s Auxiliary even after Alex’s death. On 30 November 1944, the Toronto Star covered their myriad and important activities in supporting families at home, providing solace to the bereaved, and sending packages to the men overseas. It was difficult, but “when you think that we are working for such a fine group of men,” she said, “it helps.

“I don’t think you ever get over it, you never do”

In 1996, his son, Robin, wrote:

I don’t think you ever get over it, you never do. He was a wonderful father to me the short time he was with me. Some things we did together are still quite fresh in my mind. I was only seven when he enlisted. One of my last memories is the summer when the Argylls were at Niagara-on-the-Lake. My mother, my sister, and I rented a cottage in the town and I used to ride my bicycle while he had his platoon out on route marches. It’s still quite vivid.

My mother was never the same, she never had another man in her life. She died relatively young and, although she never got over his death, she kept her thoughts to herself. Christmas was particularly hard thereafter, and the first Christmas was especially so. We never talked much about it.

I remember VE Day with mixed feelings. We were glad it was over and that the soldiers, the Argylls, would come home — all except my dad. It was a difficult time. My mother wasn’t bitter. The Logie family had a very long military tradition and she accepted, as did we, his decision to enlist. But it bothered her that some men whom she knew who could have enlisted, didn’t. What was more galling was that they made quite a lot of money during the war.

“And everything that I find out about him makes me proud to be his son”

I loved my father and miss him to this day. He seemed wonderful to a young boy of seven. Later in my life, I learned what sort of a man he really was. When I attend an Argyll function, it never fails but that someone knew him, tells me a little more about the father I knew so briefly. And everything that I find out about him makes me proud to be his son.

In 2003, the Logie family presented a beautiful portrait of Alex Logie’s father, one of the founders of the Regiment and its first commanding officer, Lt-Col William Alexander Logie. It was donated in memory of Major Alexander Chisholm Logie (1906-44).

In 2013, Robin and Joy presented a charcoal portrait of their father for the Savard Room of the Officers’ Mess; there were almost 20 members of the Logie family in attendance.

“It’s for Skin [the troops’ nickname for Logie], always has been, always will be”

From the end of the war until their deaths, the men of 18 Platoon, D Coy, made a habit, whenever they were together, of raising their first glass to the heavens. I wondered aloud once as to the nature of this ritual. As Pte J.N. “Mac” Mackenzie explained, “It’s for Skin [the troops’ nickname for Logie], always has been, always will be.” This is the sort of honour that no one can bestow; it is earned, never awarded. And, in his life, Alex Logie more than earned it.

Between 16 and 19 October there was a brief respite from battle. No Argylls were killed or wounded.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Note: There are several poppies for Maj Logie in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Logie at Niagara Camp, c. 1941

Logie with his daughter, Joy

Obituary, Maj A. C. Logie

Maj Alex Logie’s grave marker in the Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery.

Logie grave memorial, Hamilton Cemetery

Portrait of Lt-Col William Alexander Logie by Katherine MacDonald, donated by the Logie family in 2003. Argyll Officers’ Mess.

Charcoal portrait of Maj A.C. Logie by Lorne Toews