Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan (K 55109) (1913–45)

Introduction

The Argyll Regimental Foundation’s website regularly receives queries by email or, at times, regular mail relating to the history of the Regiment but, more usually, about those who served, or may have served, with it.

In late February, Geordie Proulx, QC, a senior Crown Counsel in Vancouver, wrote me a long letter about his dad, Lt Grover Proulx, Scout Platoon. He was wounded and taken prisoner during a four-man recce patrol on 23 April 1945. The letter mentions the one Argyll killed on patrol that fateful day, Private Colin Robinson “Buddy” MacLennan. Grover Proulx’s story is intrinsically fascinating because he became friends with the German soldier who shot him, captured him, and befriended him in a German field hospital. Since receipt of Geordie’s letter, we have corresponded frequently about his father and Buddy MacLennan. I am grateful to Geordie for his invaluable help in remembering Buddy and to a friend who translated a unique German document found in Pte MacLennan’s personnel file. This, then, is Buddy’s story.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan (K 55109) (1913–45)

KIA 23 April 1945

“So I think you and I were more lucky”

(Heinze Brune to Lt Grover Proulx)

Soldiers often consider luck to be a crucial element to survival in battle. German paratrooper Heinze Brune shot and wounded Lt Grover Proulx in a brief firefight on 23 April 1945. One of Brune’s comrades shot and killed one of Proulx’s men. For Brune, in reflection after the war, the difference in their fates came down to luck and nothing more. On that day, Pte Colin MacLennan, who had seen plenty of action from mid-September 1944 to late April 1945, was less lucky.

One hundred years before Colin MacLennan enlisted in 1940, his forebears had immigrated from the isle of Lewis in the Scottish Outer Hebrides to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The economic structure of the northwest Highlands that had taken shape between 1760 and 1815 was collapsing. Kelp was one of the mainstays of the Hebridean economy, and its price fell steadily through the 1820s and the 1830s. The potato crop, the new staple of Highland life, partially failed in 1836 and 1837; the result devastated the Outer Hebrides. In 1844, four years after Peter MacLennan and his family left, the descendants of the Earls of Seaforth (Clan Mackenzie), who owned Lewis, sold it to Sir James Matheson, the great opium trader.

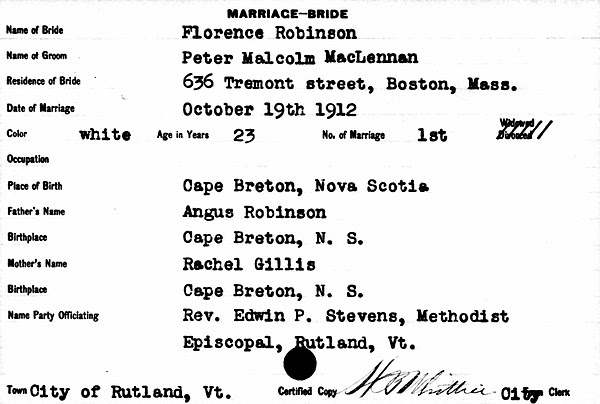

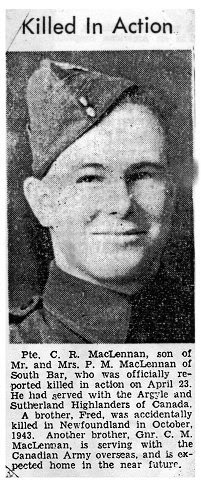

Colin’s father, Peter Malcolm MacLennan (1887–1969), hailed from Baddeck, Nova Scotia. Prior to the First World War, he lived and worked for a time in Massachusetts. On 19 October 1912, he married Florence Robinson, another Cape Bretoner; they already had one son, Frederick. Colin was born in Boston on 1 November 1913. The family returned to Baddeck in 1914, and the following year, Peter, 6’ tall with blue eyes and brown hair, enlisted and served with the renowned 85th Battalion (Nova Scotia Highlanders).

“Improperly Dressed”

Colin received his schooling in Baddeck and left at the age of 12, having completed grade 8. Prior to his enlistment on 1 May 1940, he worked for his father as an assistant lighthouse keeper at Bay St Lawrence, Aspby Bay, Victoria County, in northern Cape Breton, a beautiful and remote area. For the post-war, his expressed ambition was “Radio Work.” Colin was 5’ 6”, 144 lb, with grey eyes and light brown hair; he was a Presbyterian, as was the rest of his family. MacLennan’s military career in Canada was a varied one. Taken on strength with the Cape Breton Highlanders on 7 May 1940, he was attached to the Home Guard on 10 July and No. 6 Heavy Battery of the Royal Canadian Artillery at Sydney, Nova Scotia, on 10 July 1940. After a furlough in December, he was hospitalized with measles and influenza from 20 December 1940 until 2 January 1941; he was in hospital again for 6 days in April and another 5 days with bronchitis in May 1941; he was attached to No. 103 Heavy Battery in Amherst, Nova Scotia. After another brief hospitalization in July, he lost 7 days’ pay for his part in a disturbance in barracks. To add insult to injury, he was “Improperly Dressed” for the brawl. On 3 August, he went AWOL for 3 hours and 15 minutes, a lapse that cost him 7 days confined to barracks.

In March 1943, Colin entered hospital in Amherst; by 6 May 1943, he was promoted from gunner to lance bombardier stationed with the 103rd Battery in St John’s, Newfoundland; he spent 13 days in hospital there with metatarsalgia (inflammation of the ball of the foot); doctors hoped that an adjustment to his boots would help (apparently it did because there is no subsequent mention of the problem). On 19 November, he transferred to the 52nd Battery in Halifax, where he went AWOL in January 1944, resulting in a demotion back to gunner. In February 1944, he was “reallocated” to the Canadian Armoured Corps and underwent training at No. 24 Basic Training Centre in Brampton, Ontario. Old impulses did not die and, once again, Colin was AWOL until apprehended by military police in Woodstock; he received another 7 days of confinement to barracks. By May, he was in Calgary undergoing further training. He went overseas on 4 August 1944 and reported for duty in the UK on the 11th with No. 4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit. Taken on strength to the X-4 list (unposted reinforcements) with 2 Canadian Base Reinforcement Group, he joined the Argylls on 15 September.

Pte MacLennan was part of the first tranche of desperately needed reinforcements. The Argylls had lost heavily during the fighting from late July through to mid-September 1944. Presumably, he was posted to a rifle company. As such, he enjoyed the relative respite from battle that lasted until mid-October. There was time for further training, patrolling, and integration at the section and platoon levels, which were critical to surviving the inevitable onslaughts that lay ahead. And come they did: Watervliet, Essen, to Wouwse Plantage to Bergen Op Zoom.

The winter on the Maas River provided another needed respite. There were more reinforcements, more training, some patrolling, and time for the modest relaxation offered up in a period of relative quiet. Pte MacLennan gave himself a Christmas present and went AWOL for the day and as well as for 9 hours on Boxing Day. In the circumstances he lost 9 days’ pay. The unit was back in action for the battle of Kapelsche Veer in late January 1945 and the battle in the Hochwald Gap in late February and early March; all of these actions were bloody and the losses were heavy. From 11 March to mid April at Friesoythe, there were few casualties. Yet, once again, grim fighting resulted in gloomy casualty reports. By this point, MacLennan had joined the Scout Platoon and was with it for April’s fighting.

“brief skirmishes with small enemy parties, rearguards and patrols”

In hospital in late 1944 recovering from severe pneumonia, Cpl Harry Ruch reread the scraps of paper that constituted his diary and found them inadequate expressions of the reality experienced. In the epilogue to his diary, Ruch noted, for example, “the brief skirmishes with small enemy parties, rearguards and patrols.” Patrolling was a constant feature of life for the rifle companies and the Pioneers; it was the stock-in-trade of the Scout Platoon. Because patrols were so common, the various war diarists rarely took notice of them except on days such as the 23rd when they stood apart from the day’s relative calm.

On 23 April, it seemed to the unit’s war diarist, Lt Lloyd Grose, that the worst was over for the time being; after all, bath parades had been ordered, and reinforcements were en route to the rifle companies.

War Diary. 23 April 1945. Küstenkanal [L.G.]

No major move was expected during the day, and it was arranged to have bath-parades for the rifle-companies. One TCV load at a time made the trip to the outskirts of Friesoythe, where the Mobile Bath had been set up … There were repeated Typhoon attacks on the wooded areas to our North and North West, where the enemy guns and Moaning Minnies were believed to be set up. Several “bomb-Happy” [i.e., battle-exhausted] Germans came out of their positions after the raids to surrender to our troops.

It was estimated that since crossing the Küsten canal the Argylls had suffered 150 casualties, and we were most happy to hear that 90 reinforcements were about to proceed to F-Echelon and the companies … At last light, our company situation was as follows:

A Company … two officers and 48 Other Ranks B Company … two officers and 53 Other Ranks C Company … two officers and 45 Other Ranks D Company … two officers and 59 Other Ranks.

At 2030 hours our Scout Officer, Lieut. Proulx and three Scouts went on a patrol to recce our left flank. They ran into a German MG 42 … Lieut. Proulx and Pte. McClelland were walking along the left-hand side of the road, Interpreter-Sergeant Mos and Pte. Luke on the right-hand side, when the MG opened up on them at approximately 50 feet distance. Sgt. Mos and Pte. Luke dove into the ditch and succeeded in making their get-away, despite the fact that the enemy was firing on them continuously. Pte. McClellan [Pte Colin R. MacLennan] was found the next day, shot through the chest, and subsequent PW statements led us to believe that Lieut. Proulx was taken prisoner.

“very sticky and dirty”

Ruch’s point about the small patrols and skirmishes was that, although often overlooked, they could be “very sticky and dirty.” Such was the day’s four-man recce patrol by the Scouts. Grose, the war diarist, took note of the discovery of Pte MacLennan’s body and the wound – “shot through the chest” – and of Lt Proulx’s capture.

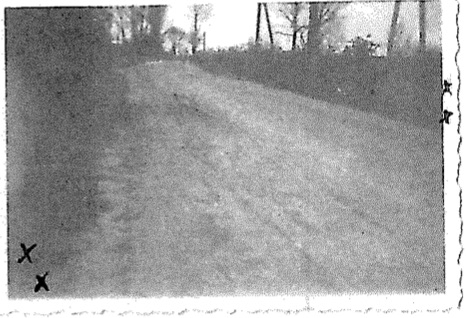

Grover Proulx survived the war after time as a POW and a considerable time in various hospitals before reaching a convalescence hospital in British Columbia. His survival is attributable, in part, to the actions that day and afterwards of the German soldier who shot him – Heinz Brune. They corresponded after the war, became acquaintances for a time, lost contact, and then reconnected and met in 1980. In the immediate post-war period, they exchanged letters, and in 1948 Brune also provided photographs of the area of the firefight.

Lt Proulx remembered Pte Colin (“Buddy” to him) MacLennan. Grove’s stories about him, about the war, and the Brune letters became part of his bequest to his wife and sons. That bequest provides a sketch of what transpired that day.

“Let’s get the fuck out of here!”

Son Geordie Proulx’s reminiscence reads:

According to my father, he had had very little sleep prior to his last patrol. His estimate was only two hours per day during the previous two weeks. His mission was to determine whether a particular farmhouse a few hundred yards ahead was occupied or defended. He set out at dusk with three other men, two of their names he told me – Nick Maas [or Mos] and Buddy MacLennan – and advanced up a small road beyond the Argylls’ line at Osterscheps … In any event, my father had the misfortune of encountering a German scouting patrol a couple of hundred yards in front of the target farmhouse.

The German scouting party saw my father’s patrol coming, stayed hidden and opened fire on my father’s patrol when they got within very short range. My father was hit in the leg and knocked into a ditch by the road which was half full of water. His rifle remained on the road. Buddy MacLennan also ended up in the ditch within arm’s reach of my father … blood was ‘welling out of his tunic at the base of his neck’ … the Germans were throwing small grenades at Dad, who was attempting to crawl away in the ditch. My father told me that the first thing he said to Buddy was, “Let’s get the fuck out of here!”

“Boss, I’m not going anywhere”

Buddy answered, “Boss, I’m not going anywhere.” He was shot through the base of his neck and died “like a soldier” within a minute, according to my father.

The German patrol wanted a prisoner. Heinz Brune of the 21st Paratroopers, 6th Division, wrote to Grover Proulx on 16 Oct. 1946, mentioning Buddy:

I am the paratrooper who wounded you in the legs. But I am very glad that I am such a good shooter and hit you only in the legs. See your fellow-soldier who received a shot threw [sic] his chest by my comrade and died shortly after it. So I think you and I were more lucky.”

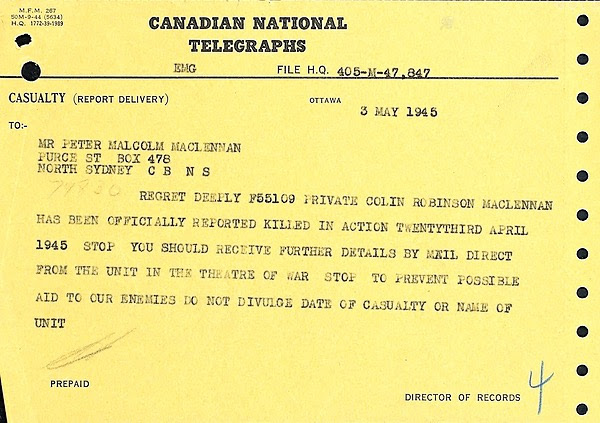

Telegram to Pte MacLennan’s father informing him of his son’s death.

Telegram to Pte MacLennan’s father informing him of his son’s death.

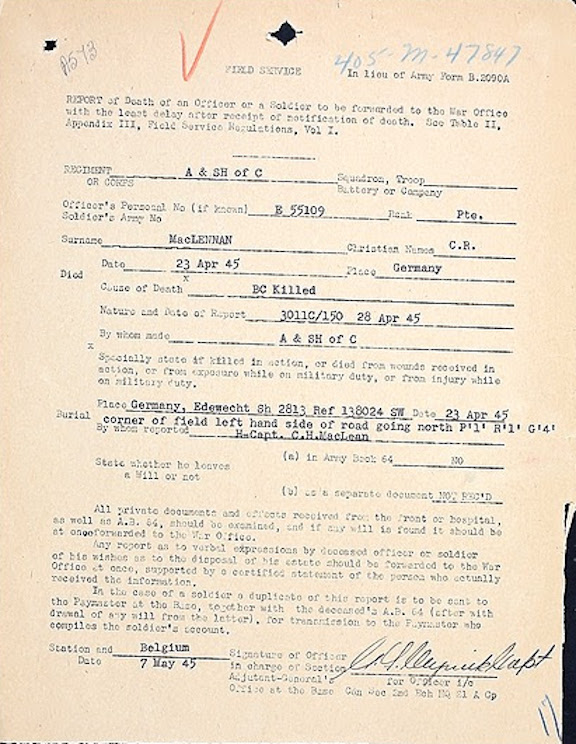

Field Service report – Pte C.R. MacLennan, 7 May 1945.

Field Service report – Pte C.R. MacLennan, 7 May 1945.

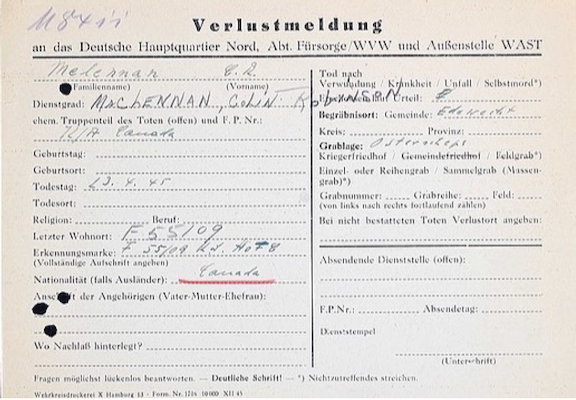

German loss report – Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan.

German loss report – Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan.

“that bloody day”

Almost exactly a year to the day later, Brune wrote again: “Allways [sic] when I think of that bloody day I thank God that you are healthy and well.” Brune’s pictures from 1948 show clearly how close the two patrols were to each other, where Buddy MacLennan and Grover Proulx ended up after being wounded, and where Buddy died. Proulx’s exhortation declares his intention to save his comrade-in-arms. Buddy’s response demonstrates the level-headed clarity of mind of a man close to death. And so he died but mere moments later. After capturing Proulx, the Germans removed both from the ditch to a nearby spot behind a hedge, as shown in Brune’s 1948 photo and caption. The German patrol was anxious to get away with their prisoner, Lt Proulx, and Brune was now wounded. They left Buddy’s body but made out, so it seems, a verlustmeldung (loss report) for him and, presumably, left it with his body, where it was recovered the next day by Argylls.

“cut down in an instant”

Forty-two years after the war, Capt Sam Chapman wrote evocatively about the “man who falls in battle … He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank. There is an end but no conclusion.” Pte Colin “Buddy” MacLennan, the single assistant lighthouse keeper who had lived on a remote stretch of Cape Breton Island, hoped to be in “Radio Work” after the war; his ambition ended that day in a short firefight between opposing patrols, “an end,” as Chapman would have it, “but no conclusion.

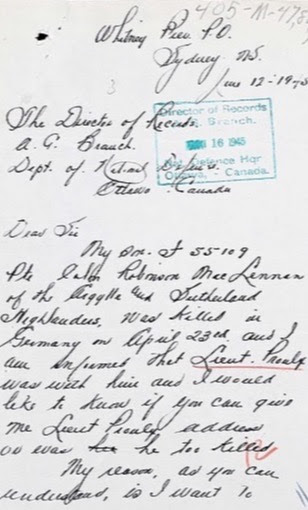

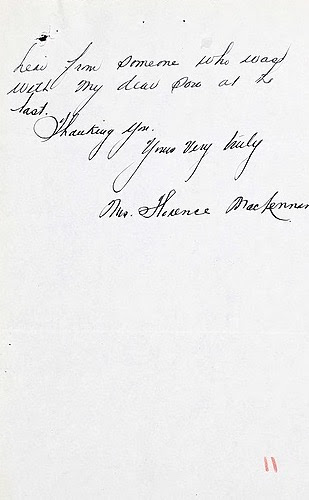

“I want to hear from someone who was with my dear son at the last”

Pte MacLennan left little, very little. The inventory of his personal effects is astonishingly bare; there is but one listing – 2 rings. Most soldiers had a collection of souvenirs, personal items, letters, and photos, but not Buddy. Peter MacLennan received the life-altering telegram reporting his son’s death on 3 May 1945. The family also received letters from the unit, almost certainly from Padre Charlie Maclean and probably from others as well. Certainly Maclean always provided as much information as he had, and he knew its importance to families. When Florence MacLennan wrote to the Director of Records on 12 June 1945, she was “informed that Lieut. Proulx was with him and I would like to know if you can give me Lieut Proulx[’s] address or was he too killed[?] My reason,” she wrote, “as you can understand, is I want to hear from someone who was with my dear son at the last.”

“Buddy died like a soldier”

Many grieving Argyll wives or parents wrote similar letters, anxious for further details. Florence MacLennan got her wish. Grover Proulx survived the war and he did write to the MacLennans. Son Geordie Proulx remembered:

He did tell me, though, that he wrote to his [Buddy’s] parents or mother after the war but not exactly when he did so. I remember asking him, when I was just a young teen, what he said in the letter. I remember him simply saying that [he] wrote that “Buddy died like a soldier” as at that time he had not fully described to me the circumstances of Buddy’s death … This is based upon my distinct recollection of what my father told me over 50 years ago as a boy. I knew enough even then that this was the highest of praise and have never forgotten my father’s words.

In a letter to the Paymaster General (19 December 1945), Florence inquired about the release of any moneys owing the estate. Her husband had been “released from his job as light keeper on account of ill health.” He had but a small pension and she used her sons’ assigned pay to cover his hospital bills. She had three sons: “two Made the supreme sacrifice and my third son [Calder Malcolm] is now at home with his wife and family.” Colin’s older brother, Frederick (1912-43), had died on duty in Newfoundland in October 1943.

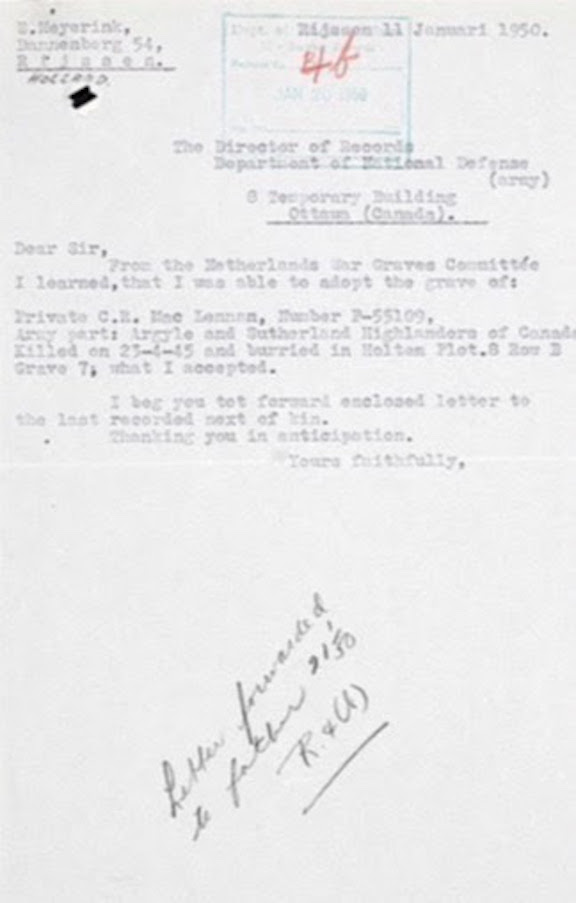

Letter written 11 January 1950 by E. Meyerink of Rijssen, Holland, regarding adoption of Pte MacLennan’s grave.

Letter written 11 January 1950 by E. Meyerink of Rijssen, Holland, regarding adoption of Pte MacLennan’s grave.

“freedoms and benefits we enjoy today were paid for with the lives of countless thousands of the Buddy MacLennans of the world”

In 1950, a Dutch family adopted Pte MacLennan’s grave in Holten Canadian War Cemetery and tended to it; the Dutch do not forget Canadian sacrifice, Argyll sacrifice; neither did Geordie Proulx:

The words have stuck with me ever since. In the summer of 2016, I took my son, then 20, to Buddy’s grave in Holten and told him everything I knew of how Buddy died. It was my way of teaching him that the freedoms and benefits we enjoy today were paid for with the lives of countless thousands of the Buddy MacLennans of the world. And he must never forget it.

Between 21 and 23 April 1945, 8 Argylls were killed in action and 54 wounded.

“a history bought by blood” – Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

In memory of my father, Lt Grover C. Proulx, who was with Pte MacLennan when he died and never forgot him – ‘he died like a soldier.’” – Geordie C. Proulx

Note: Pte MacLennan’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

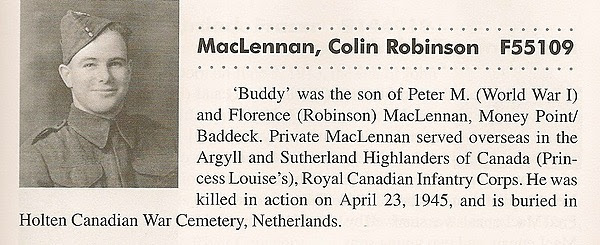

Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan.

Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan.

Marriage certificate: Peter Malcolm MacLennan and Florence Robinson, Rutland, Vermont, 19 Oct. 1913.

Marriage certificate: Peter Malcolm MacLennan and Florence Robinson, Rutland, Vermont, 19 Oct. 1913.

Lt Grover Cleveland Proulx.

Lt Grover Cleveland Proulx.

Heinze Brune sent these and the following three images, all dated 23 Feb. 1948. He wrote on the back of the image above:

Heinze Brune sent these and the following three images, all dated 23 Feb. 1948. He wrote on the back of the image above:

“the street you came across

x our positions.”

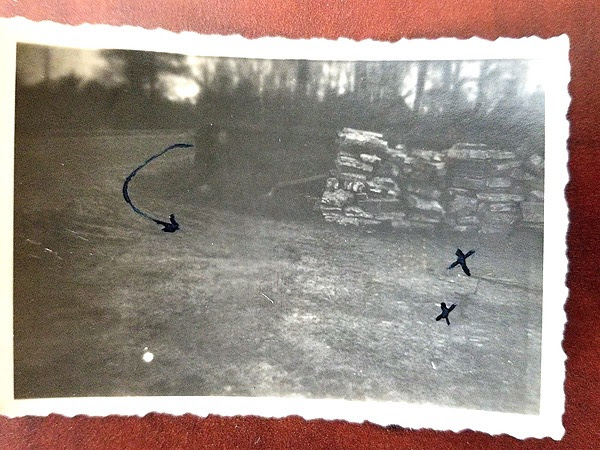

Brune wrote on the back of the image above:

Brune wrote on the back of the image above:

“xx lying in ditch

x our position behind hedge.”

Brune wrote on the back of the image above:

Brune wrote on the back of the image above:

“you two brought behind this hedge.”

Brune wrote on the back of the image above:

Brune wrote on the back of the image above:

“xx after being wounded your comrade and you in the ditch.”

Letter from Florence MacLennan, Sydney, N.S., to the Director of Records, 12 June 1945.

Letter from Florence MacLennan, Sydney, N.S., to the Director of Records, 12 June 1945.

Gravestone of Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan in Holten Canadian War Cemetery, Netherlands.

Gravestone of Pte Colin Robinson MacLennan in Holten Canadian War Cemetery, Netherlands.