Note on Revised Text: More Information on the Disappearance of Pte Wilfred Ernest Madaire

Last year I spent considerable time ruminating about the Argyll action at Veen in the early morning hours of 7 March 1945. I wrote about three of the Argylls killed there (Madaire, Pte Edward Robertson Smith, and Pte Clarence Richard Vaise). A number of readers were enthralled by the tales of their brief lives and violent deaths. The tale of the battle and the ubiquitous confusion that attended it provide its own fascination.

I have been writing a long piece on the battle itself, which I shall post in the near future. My understanding of the day’s events is clearer (perhaps somewhat clearer would be a more apt description) by the efforts of a number of people intrigued by Veen. At the centre of this group is Jonathan Earp, son of Col Alan Earp, who commanded the Pioneer Platoon from November 1944 to 14 April 1945.

Jonathan and his wife, Frau Anja Witt, live in Germany about an hour’s drive from Veen. They drove the route from Sonsbeck to Veen and Anja, through her contacts, found several people willing to help. She explained the project – the mystery surrounding Pte Madaire’s death – and persuaded them to devote time, talent, and energy to the search.

I acknowledge the contribution by Jonathan and Anja and that of Frau Bettina Witt at the archives in Alpen and Dr Ralph Trost, a Second War historian at Xanten. Their contributions were, as Jonathan Earp puts it, considerable. I offer my thanks to all of them. Jonathan Earp has provided translations from the German.

Today on the 76th anniversary of the Argyll battle of Veen, I offer a revised biography of Pte Madaire that incorporates the research undertaken by the aforementioned group.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

7 March 2021: 76th Anniversary of the Battle of Veen

Introduction

In February 2020, I was considering the battle for Veen on 7 March 1945 and the nine Argylls who died there. All but one was a recent reinforcement and the names largely unknown to me. The name at the top of the page was “Madaire, Wilfrid [sic] E.” Several French Canadians had served in the 1st Battalion, and I looked up his file on Ancestry.com. I also located his niece, Lou Madaire, who facilitated an interview with her aunt, Wilfred’s sister.

Pte Madaire disappeared on 7 March 1945 and his body was never found. A post-war report by the Argylls suggested the possibility of confusion; perhaps Pte Madaire had not served with the unit. Although in November 1945 the army council confirmed his death for estate and administrative purposes, his mother hoped for the remainder of her life that, someday, her son would return.

What happened to Pte Madaire? This question led to an intensive examination of the records for the two company attack on Veen that fateful night. Confusion is the dominant motif, and I will post a long piece on Veen in December. I have filled in a lot of gaps but precise answers are yet to come.

I am, of course, grateful to Lou Madaire and Laurie (Madaire) Guilbault, who shared images and recollections with me. My gratitude goes to Lt Alan Earp, who has responded with his customary insight on my attempts to understand what happened on 6-7 March 1945.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

November 2020

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Pte Wilfred (Wilfrid) Ernest Madaire, 1st Bn Argylls (1921–45)

Disappeared 7 March 1945

When Sam Chapman penned the words above in 1987, he had in mind all of the Argylls killed in action, each “cut down in an instant with all his future now a page to remain forever blank.” For Private Wilfred Madaire, there was certainly an end, but for his family, because of the circumstances of his disappearance, there was never a conclusion. Madaire’s journey from Canada to a battlefield in northwest Europe was a long and somewhat convoluted one; he was one of the thousands of reinforcements desperately needed by infantry battalions bled by battle. The Argylls’ history was “bought by blood,” as Chapman would have it. Although Madaire’s time with the battalion was achingly short, his story is part of its history and his blood a part of its price.

Pte Wilfred Madaire’s fate was tragic and all the more so because his hopes upon enlistment had not included the infantry. His long odyssey from Canada to an operational theatre and the Argylls occurred within those fateful, frantic days during the battle for the Hochwald Gap. Upon their arrival, the exhausted, battle-weary battalion posted its desperately needed reinforcements to its depleted rifle companies. Lt Grose thought reinforcements needed “several weeks [’] training to properly adjust themselves to the Battalion.” For those arriving in late February and the first days of March, additional training was not to be; there was a battle to be fought on the Argylls’ immediate horizon.

Madaire’s name appears on the lists of reinforcements in Part 1 orders for 28 February 1945; officially, he was posted to D Company (Coy). He may have gone to B Coy by mistake or intermingled with them during the confusion of the night assault that began about 0100 hours on 7 March. What is certain is that he met his fate with B or D on that dark, cold night.

“home life good”

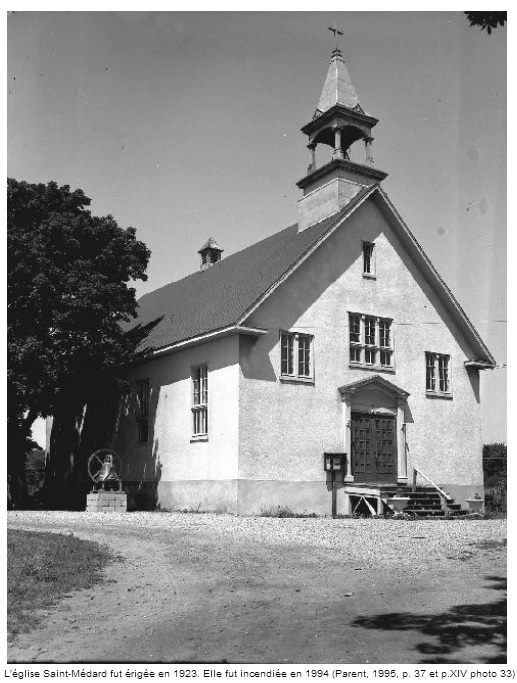

Joseph (his baptismal name) Wilfred (sometimes Wilfrid in documents) Madaire was born on 4 December 1921 in St-Paul, Aylmer, Quebec, to Alexandre Israël Madaire (1889-1972) and Olivine M. Delima Lodovide Rhéaume (1894-1977), who had married in Ottawa in 1917. Laurie Guilbault (Madaire), Wilfred’s younger sister, explains that her family had its roots in Deschênes (now part of Aylmer), where they were “all born.” It was “a religious family and,” she added emphatically, “we still are.” She described their “home life [as] good.” During the war, army interviewers would not disagree and later wrote “normal” in the appropriate field on the form. French was the language spoken “at home,” although all members of the family “picked up” English. In Deschênes, family life centred on the parish church, St-Médard, where French was the language of service. Madaire started school at 7 and had completed 6 months of a “machinist’s course, [at] Hull Technical School.” He “stopped at 16” because of the “opportunity of getting [a] job.”

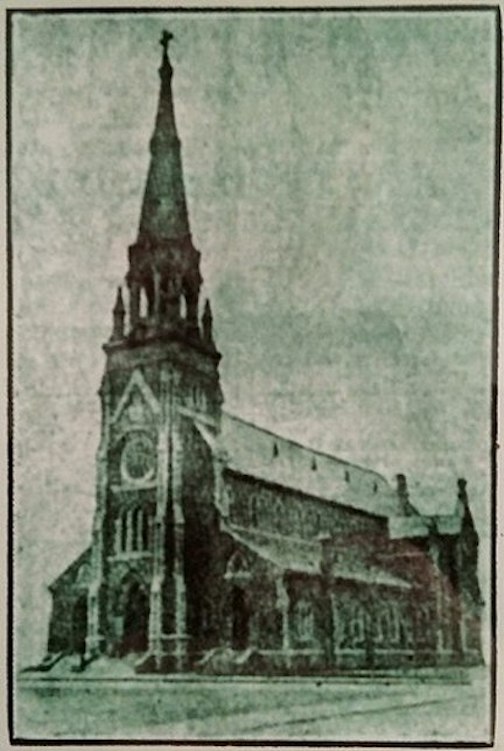

The family remained in Deschênes until Alexandre became “plant electrician” with Ottawa Dairy Limited on Somerset Street West in Ottawa. He bought a house “close by” (on Somerset), and here the Madaires lived, in Centretown. Alexandre was mayor of Deschênes from 1937 to 1944 (usually by acclamation, according to daughter Laurie), but the family now attended church at St Patrick’s Basilica, Ottawa, where services were in English.

Young Wilfred worked as a file clerk for Acme Office Supply in Ottawa for one year, earning $12 to $25 weekly; he then became a jewellery finisher and maker in Hull for nine months (piece work) before crushing his finger and leaving. Prior to his enlistment on 18 November 1942, he was a production manager’s assistant in the ice cream department of the Ottawa Dairy Company (his father’s company) for two and a half years, earning $35 weekly.

“bilingual … above average learning ability”

Wilfred was “bilingual” and considered by the army to have “above average learning ability” (according to his enlistment interview of 5 March 1943). The army had figured among young Wilfred’s extracurricular interests prior to enlistment. He had spent five years in the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa; attended four summer camps with them; and, for two years, was the unit’s medic following a first aid course with St John Ambulance; he qualified as a stretcher-bearer.

“preferred to go in the Navy as a Sick Bay Attendant”

A “tall, young man (5’, 8”) of slight build” (138 lb) with hazel eyes and brown hair, Madaire “would have preferred to go in the Navy as a Sick Bay Attendant.” His older brother, Roger Édouard Madaire (1918-47), was already serving overseas. As for Wilfred, he was in “good health and has never been seriously ill.” He played “some” hockey and softball “on junior teams.” Golf, however, was “his favourite sport.” He also enjoyed tennis, skiing, and swimming. He:

… reads English authors with [a] view to improving knowledge of that language; also comics for relaxation. Spends evenings reading at home, at moview [sic], or with lady friend. Hobby of badge and book collecting.

As for post-war plans, Madaire wanted to “Return to School.”

“Agreeable, neat”

On 18 November 1942, he enlisted and was taken on strength at the Central Ordnance Depot in Ottawa as a private in the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps. Admitted to the Rideau Military Hospital on 23 March 1943, he was discharged on 15 April and returned to duty. On 25 August 1943, he was posted to No.1 Transit Camp in Windsor, N.S., proceeding overseas on 13 September. “Agreeable, neat,” and “sturdy,” he hoped, in September 1943, to become a machinist in the army. This time, however, the personnel officer conducting the interview considered him of “below average learning ability” with the proviso that he was “sincere” and “probably tries hard.” Because he was “not a prospect for courses of an advanced nature,” the officer recommended him for “driver.”

“as G.D.” [General Duties] Infantry”

Madaire’s life in the United Kingdom consisted of a series of transfers and one remustering punctuated by a handful of minor military infractions. Taken on strength with 1 CORU (Canadian Ordnance Reinforcement Unit) on 14 September, he transferred to the RCOC (Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps) on 19 November 1943. On 28 January 1944, he was awarded 7 days’ field punishment and a fine for disobeying a lawful command by his superior officer. Then, on 31 March 1944, he received 10 days’ field punishment for “neglecting to obey unit order. Forf[eits]s 10 days [of pay].” Effective 15 May, he transferred to “1 Sub Workshop, RCEME [Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers]. On 8 August 1944, he was confined to barracks with a loss of three days’ pay “in that he failed to change his quarters when ordered to do so.” On 29 October, he transferred to 1 CGRU (Canadian General Reinforcement Unit); he was then taken on strength at 2 CITR (Canadian Infantry Training Regiment) on 10 November 1944 following his remustering as “as G.D.” [General Duties] Infantry.” Infantry battalions such as the Argylls badly needed reinforcements after the battles from June to November 1944 and then again after the early losses in 1945 [see Pte Alexander Nickoloff and LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr]. He went AWOL on 5 December 1944, returning six days later; he forfeited “7 and 21 days of pay.” On 9 January 1945, he received 5 days confined to barracks and 4 days forfeiture of pay; he had been AWOL again. On 27 January, he transferred from 2 CITR to the X-4 list (of unposted reinforcements).

Madaire’s long sojourn in the UK ended on 28 January 1945 when he embarked for northwest Europe; three days later he was there. It was only a matter of time before he would join an infantry battalion in the field. On 27 February, he was struck off strength from the X-4 list and taken on strength with the Argylls the following day, when he was posted to D Company. As previously mentioned, the Part 1 appendix to the unit’s war diary is clear on this matter. That, however, is all that is clear.

After the failure of a combined arms attack on Veen on 6 March, Lt-Col Fred Wigle, the Argylls’ commanding officer, on orders from brigade, decided on a night-time infiltration by two rifle companies, B and D. The plan was folly from the start: how would a much smaller force without tank or artillery support succeed against a well-defended small fortress of a town fiercely held by determined paratroopers when a larger, heavily-gunned force had already failed to breach the town’s outer defences?

“not being able to see ‘shit’…”

The companies moved to the start line and moved off under a creeping artillery barrage. It was a challenging task for well-trained troops, but for new reinforcements, many with no experience of battle, and at night, it proved extremely exacting. Troops became confused and lost their way. D Coy had immediate casualties from the friendly fire, one of whom died. Elements of D Coy intermingled with B, where they remained. The route had not been reconnoitred; B Coy’s 18-set (its only means of communication with the battalion’s tactical headquarters) failed; elements of both companies bumped into the enemy in the darkness and became prisoners; the two company commanders (one almost certainly suffering from battle exhaustion) disagreed on a plan (one decided to attack, the other asked for permission to withdraw and received it); and the attacking coy (B) was down to two platoons, engaged in a heavy firefight from enemy trenches against powerfully defended buildings, charged across open ground, was repulsed, and captured at day break by a superior force. The seeds of confusion were sewn heavily that night. Pte Peter Leslie Ginn, a Newfoundlander from Grand Falls, told his son “a story of marching/sneaking to a location behind enemy lines in the middle of the night not being able to see ‘shit’…” It was almost certainly this night: Ginn’s buddy, Pte Ernest John Howe, a Mi’kmaq from Nova Scotia, was captured that night when the two of them were clearing a house, presumably in Veen or on its outskirts.

Fifty-one Argylls were killed, wounded, and/or captured. Of that number, only 2 had been with the unit before 9 September 1944; 17 joined as reinforcements between 9 September and 29 November; and 32 were taken on strength between 9 January and 7 March (most arrived in February, many in late February/early March). Pte Madaire’s situation, as a very recent reinforcement, was by no means unique; 24 of them joined the unit between 28 February and 7 March. Of the 51, 22 were from B Coy; 21 from D; and 8 from other companies; plus 6 from C Coy and 2 from Support, including Pte Howe.

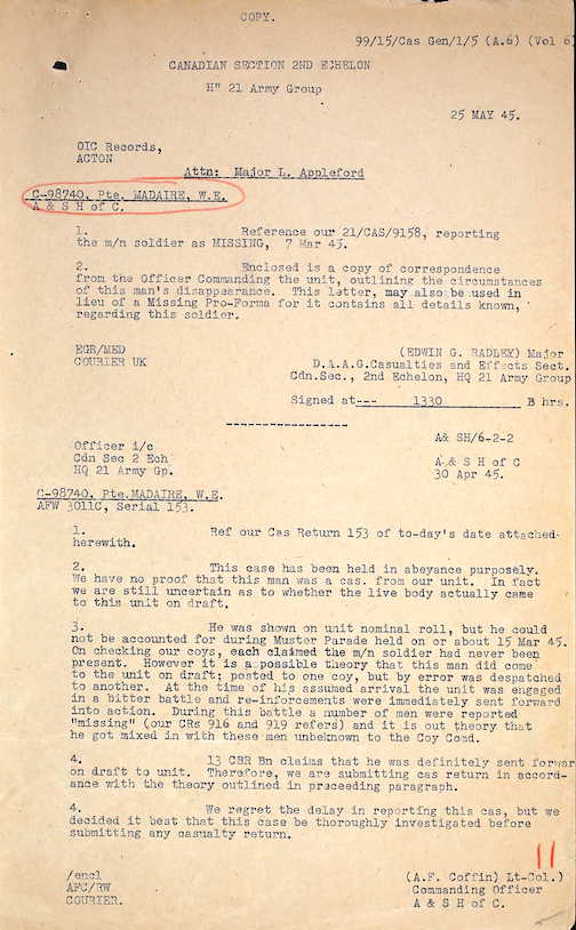

“a possible theory that this man did come to the unit”

Pte Madaire went missing that fateful day. On 15 March the Argylls held a “muster parade.” Madaire was on the nominal but was not present and no one from any company could account for him. The unit “thoroughly investigated” before submitting a report. LCol Bert Coffin, CO of the Argylls, filed a report on 30 April 1945 with the Canadian Section, 2 Echelon, HQ, 21 Army Group, regarding the unit’s casualty returns and Madaire. The unit “held” his case “in abeyance purposely. We have no proof that this man was a cas. from our unit. In fact, we are still uncertain as to whether the live body actually came to this unit on draft.” Although he “was shown on [the] unit nominal roll … he could not be accounted for during Muster Parade held on or about 15 Mar 45.” Worse, upon:

“checking our coys, each claims the m/n soldier had never been present. However it is a possible theory that this man did come to the unit on draft; posted to one coy, but by error was despatched to another. At the time of his assumed arrival the unit was engaged in a bitter battle and re-enforcements were immediately sent forward into action. During this battle a number of men were reported ‘missing’ … and it is out [our] theory that he got mixed in with these men unbeknown to the Coy Comd.”

Coffin noted that “13 CBR Bn claims that he was definitely sent forward on draft to unit.”

Argyll report of missing Pte Madaire, 20 April 1945.

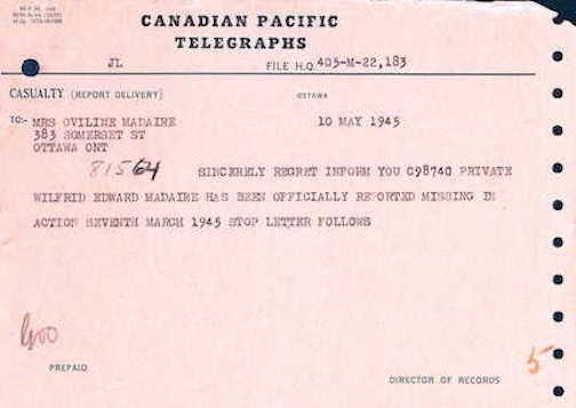

The mystery of Pte Madaire’s fate needed more information. The Director of Records sent a telegram to his mother on 10 May; he was now “officially reported missing in action.” The following day Col C.L. Laurin, director of records, wrote to Mrs Olivine Madaire regretful that further information about her son’s status “has been delayed.” Canadian Military Headquarters Overseas “are investigating the reason for this delay with your son’s Unit in the field and you may rest assured that further information will be forwarded to you immediately upon receipt in this office.”

Telegram to Pte Madaire’s mother, 10 May 1945.

“He had suffered considerably from loss of blood”

The battalion’s inability to determine Madaire’s presence conclusively or otherwise is explained by the circumstances: heavy losses to B and D Coys, many of whom ended up as POWs, and the predominance of recent reinforcements like Madaire himself within both companies. On 27 June, Laurin requested that Pte Edward Wilkie Palmer, who “was in the same action,” be interrogated with a view to ascertaining the fate of Pte Madaire.” Laurin had corresponded with Olivine Madaire on 13 July and, eight days later, replied to her letter of 17 July. Pte Walter L. Doyle, D Coy, a POW from the Veen battle, stated:

I had occasion to know Pte. Madaire as I was a stretcher bearer in his ‘Coy’. At approx. 0100 hrs, 7 Mar 45, Pte Madaire was wounded by shrapnel in the right

leg, neck and left arm and shoulder apparently broken by a blast from a shell. At approximately 0400 hrs. 7 Mar 45, we were surrounded and captured by the enemy.

Pte Madaire was taken by stretcher and eventually placed on an enemy vehicle and taken to an enemy F.A.P. since that time, I have heard nothing as to what has

happened to him. He had suffered considerably from loss of blood and although I cannot be certain, to the best of my knowledge he could not recover due to the loss of blood and lack of medical aid.

“very little hope that he is alive”

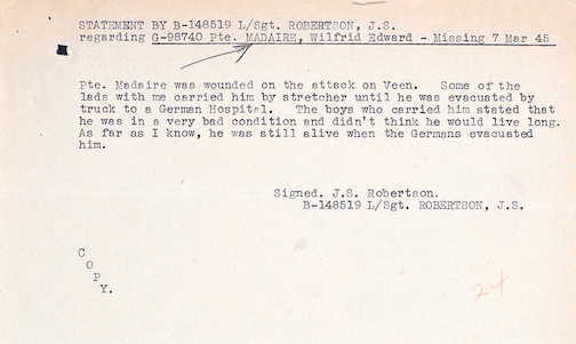

Laurin pointed out that the statement “does not officially establish your son’s death, but … there seems to be very little hope that he is alive.” L/Sgt John Robertson, D Coy, another Argyll POW, stated:

“Pte. Madaire was wounded on the attack on Veen. Some of the lads with me carried him by stretcher until he was evacuated by truck to a German Hospital. The boys who carried him stated that he was in a very bad condition and didn’t think he would live long. As far as I know, he was still alive when the Germans evacuated him.”

Statement by J. S. Robertson.

“Madaire …and appeared to be dying”

In July 1945, a number of repatriated Argylls stationed in Windsor, N.S., made statements. On the 13th Pte Richard S. Evans, B Coy, recalled:

The last time I saw Pte. Madaire was at the German RAP at Ven [Veen]shortly after we were captured.

At this time Madaire was in a very critical condition and appeared to be dying.

I was then taken back from the RAP a mile or so to a barn and did not see Madaire again.

Cpls. [Frederick A.] Smith [D Coy], [A/Cpl Edward] Randall [B Coy] and Pte [L/Cpl] George Lees [Lee, B Coy], numbers and initials unknown, remained at the RAP to have their wounds dressed after we had been taken back, and may be able to provide further information …

Pte O.H. Maxner, B Coy, who was neither wounded nor captured at Veen, made his on the 20th:

“I am very sorry, but the above mentioned soldier was not known to me. He may have been a reinforcement who joined the Unit just previous to his being listed as Missing.”

Pte Edward W. Palmer, B Coy, offered his recollections on the 31st:

“I was with the same company … the last I saw of Pte. Madaire was on the night of 6 March when we were in a marshalling yard getting ready for a night attack. He was in a different Platoon to mine when I saw him, but his platoon moved forward and I never say him after that.”

I heard from one of the chaps, whose name I cannot recall, that he had been taken prisoner.

“ … was wounded and taken prisoner and sent to a German Military Hospital”

Although Argylls from different companies claimed Madaire was in the same company, it is clear that Pte Madaire was with B and D Coys and that he was severely wounded by shrapnel from shell fire. Pte Doyle, one of D Coy’s stretcher-bearers is explicit about timings. Madaire was wounded about 0100 hours, possibly he was one of the Argylls mentioned by Capt Chapman who were caught in the creeping barrage at the start-line. Chapman left a stretcher-bearer with them. According to Doyle, they were captured by Germans at approximately 0400 hours. Other Argylls such as Pte William A. Courtney, and LSgt Robertson were also captured in the period before the final attack by B Coy’s two platoons and assorted Argylls from other companies (mainly D).

After capture, Madaire was carried by stretcher and then put on a German vehicle to the German “F.A.P.” [Forward Aid Post]. Probably it was the aid post in Veen where other wounded Argylls were treated after the early morning surrender. Captured and wounded Argylls reported good treatment by their captors. LSgt Robertson states that he helped carry Madaire by stretcher until he was evacuated by truck to a German hospital. What did he mean? Is this a complementary version of Pte Doyle’s statement indicating evacuation first by stretcher, then by vehicle to the aid post at Veen? Or is Robertson suggesting removal from the aid post to a hospital?

Lt Herb Maxwell’s wounds required treatment unavailable at the German aid post, where medical resources were scant. He was removed and received treatment when it was finally available. He made no mention of other Argylls in a similar situation. The slightly wounded Argylls became POWs. The Argyll dead remained on the battlefield until after Veen was captured on the 9th. When Argyll companies moved into Veen, Pte Don Pruner of 12 Platoon, B Coy (the lost platoon) remembered marching up the road and seeing “bodies laying out in the field … dead, where they had been killed during the attack.” Veen’s civilian population remained, for the most part, in the village dwelling in makeshift bunkers. One inhabitant wrote, some ten years later, that on the morning of the 7th the townspeople “crawl out of their holes and hold their breath … The meadow is strewn with fallen Canadians.” When H/Capt Charlie Maclean wrote to Capt Perry’s wife on 3 April 1945, the good padre expressed his certainty that Perry was alive “because we found some dead [on the 9th] around the position but their [sic] was not a trace of Len, or of the other men.”

The Argylls did not find Pte Madaire’s body. Although grievously wounded, he remained alive when last seen by fellow Argylls. He was at the German aid post, which had almost no medical supplies. He did not go with Argylls who began their journey to POW camps; he was not mentioned by Lt Maxwell, who was evacuated with German wounded on the 7th.

Dr Ralph Trost reports that there is no German war diary for the Lower Rhine in this period. He found the war diary of the doctor of the II Parachute Corps. It indicated that German wounded were evacuated to the right side of the Rhine from various collection. Herb Maxwell was evacuated with the German wounded but makes no mention of any other Argyll in the same situation. Trost notes that German Army regulations required a special burial team and burial officer for Allied dead. He doubts that Madaire “would have been buried by such a burial detail, however, because of the ever increasing pressure on the German position.” He postulates ”such a thing might have happened after the fight and then presumably by civilians.”

Bettina Witt examined all death certificates for the Alpen area from 5 to 8 March 1945, with particular emphasis upon Veen and other possible areas of interest. She reports: “In the Veen cemetery there is one burial of an unknown foreigner who died 08.03.1945. There is no other information given, no name, no nationality and no cause of death. In any case he is noted in our (Alpen’s) records [not on the original certificate] as a civilian worker.” She could not offer any conjecture if the person in this grave is Pte Madaire. It would be, she wrote, “pure speculation.”

Is it possible that the fatally wounded Madaire was left at Veen, died there the following day, and was buried by local civilians? The burial on the 8th is tantalizing to be sure, but whether it relates to Pte Madaire’s fate or not remains conjecture. There are markers for unknown soldiers at many cemeteries. Dr Trost notes that Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery has 20 such graves for combatants who lacked any visible means of identification such as tags or badges on uniforms. The army’s investigation improved upon the Argylls’ report of 30 April. In the end, the Army Council made a determination, one based upon presumption and nothing more.

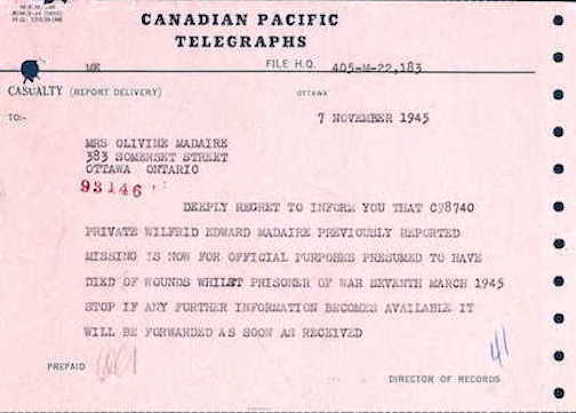

“presumed to have died of wounds whilst prisoner of war”

On 10 November 1945, Major-General A.E. Walford, Adjutant-General, wrote in a letter to Olivine Madaire that the “Army Council has been regretfully constrained to conclude that he gave his life in action … and it is consequently being recorded that [he] is now for official purposes presumed to have died of wounds whilst prisoner of war on the 7th day March, 1945.” The minister of National Defence and members of the council asked Walford “to express to you and your family their sincere sympathy in your bereavement. We pay tribute to the sacrifice he so bravely made.”

Telegram to Pte Madaire’s mother, 7 November 1945.

For the army, Madaire’s file was now closed. Their presumption about his death remains not only reasonable but also probable. For the Argylls, Pte Madaire was almost an unknown to them. Most of the two platoons of B Coy and a smattering of D Coy were killed, wounded, or captured. He was there in Part 1 orders and posted to D Coy but, in a night marked by confusion, the ones who did know him were themselves captured and/or wounded. Their story would not be told until after the liberation of POW camps and repatriation.

Capt Sam Chapman commanded D Coy that dreadful night. On 28 April he wrote to his wife:

“…I also got a letter from the mother of one of the kids who was killed by our own artillery in the Veen affair. (I didn’t tell her that.) When I came in I reported everybody who wasn’t there as missing, though I knew of several dead gave the detailed dope 6 hrs later + quite a few turned up alive. And she says that there was over a week between the telegram that said he was missing and the one that said he was killed. And because of the first they’d gone on hoping even after the 2nd till they got my letter, so I guess I slipped pretty badly there.”

“very difficult period for my mother not knowing”

As Chapman’s letter attests, other Argyll families were left wondering about an Argyll’s fate after the Veen debacle. For the Madaire family, it was different, much different. Sister Laurie was “about five when my brother left for the war” and she has only a “very scant memory.” He was “away from home a lot training.” When the telegram came describing Wilfred as missing, “I can remember she [her mother] just lost it, her hair changed colour almost overnight.” It was a “very difficult period for my mother not knowing, she kept it to herself but you could tell it was difficult.” It was doubly difficult because Roger died from injuries – war-related in 1947.” Laurie recalled that a “young man called mother. He had been in battle with Wilfred.” Apparently, he had read a notice about Pte Madaire in an Ottawa newspaper. He came to the family’s home and spoke with Mrs Madaire; he told her “it [the battle of Veen] was gruesome.”

“lived the rest of her life thinking he lost his memory and could not come home”

Laurie Guilbault’s father was the “strong, silent type” and “didn’t talk all that much,” and she cannot “recall conversations [about Wilfred] within the family” although they “spoke casually about Wilfred and Roger from time to time.” Because Wilfred’s body was never found, Olivine Madaire “lived the rest of her life thinking he lost his memory and could not come home.” She clung to the hope that someday he would recover his memory and return. Laurie knew of her mother’s private thoughts because “she told me.”

When Wilfred went off to war, he told Laurie’s mother “that she was his best girl and that when he came home from the war he would buy her a convertible and drive her around.”

Olivine Madaire waited for that ride for the rest of her life. Wilfred’s family does not forget him. Laurie’s husband served in the regular forces, as did their eldest son, who visited Wilfred’s marker in Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery. Their youngest son is in the reserves. Military service has been central to their lives, and Pte Wilfred Madaire remains a part of their story.

The famous quote about the so-called “fog of war” provides a poignant metaphor for Pte Wilfred Madaire’s life and death as an Argyll in the war.

Between 1 March and 7 March 1945, 15 Argylls were killed in action, 32 wounded, and 32 POWs.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Remembered respectfully – An Argyll

Note: Pte Madaire’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Wilfred Ernest Madaire

Olivine and Alexandre Madaire with two children, possibly Roger and Wilfred.

St-Medard, Deschênes, Quebec, 1947.

St Patrick’s Basilica, Ottawa.

Advertisement for Ottawa Dairy Ltd., 1927.

Wilfred Madaire with Gabrielle Bourgeois.

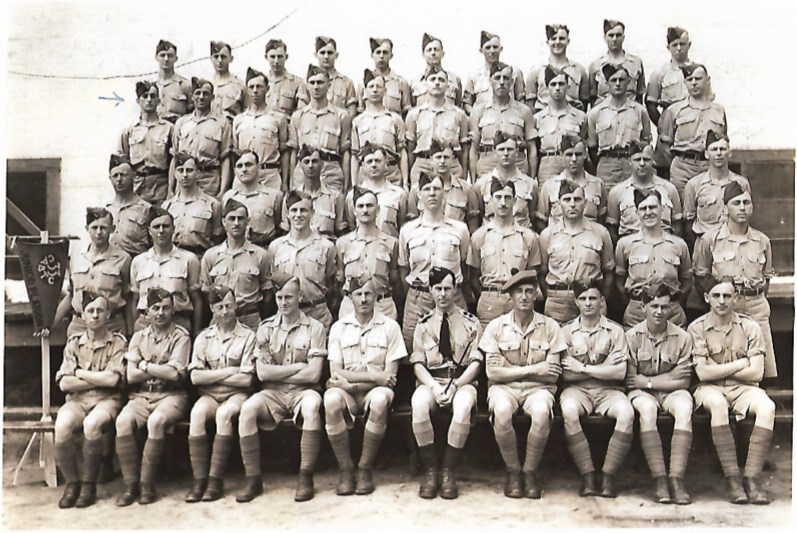

A training group of Canadian soldiers. Pte Madaire is on the far right, front row.

Destruction of Sonsbeck. The battle group of 6 March moved out from a spot near Sonsbeck, which had been captured the previous day.

Argylls near Veen, 7 March 1945.

Argyll chow line at Veen, 7 March 1945.

Pte George Francis Kelly at Veen (KIA 17 April 1945).

Obituary, 13 November 1945.

In memoriam Pte Madaire, 7 March 1947.

Olivine and Alexandre Madaire in the 1960s.

1945 Ford convertible. Pte Madaire told his mother “that she was his best girl and that when he came home from the war he would buy her a convertible and drive her around.”