Introduction

The 1st Battalion’s wartime establishment was approximately 800. When the unit returned from its 22 months in Jamaica in May 1943, it lost large cadres of officers and NCOs who were too old for overseas service and a host of others for medical reasons. There was a large intake of reinforcements in May/June, again in August 1943, and again in January 1944.

LCol Ian Sinclair, DSO, MC, ensured that the long sojourn in Jamaica did not inhibit rigorous preparation for battle. He established a training centre in the mountains and rotated the companies through it continuously during the unit’s long “sojourn in the sun.” When LCol Dave Stewart took over the battalion in September 1943, training intensified and at all levels.

“a reinforcement crisis”

Maj R.D. “Pete” MacKenzie thought that the tactical brilliance displayed at Hill 195 would not have been possible later in the war. Simply put, the unit had lost too many – far too many – well-trained soldiers at every rank level and never regained the sort of proficiency that accompanied that state. The stark reality of combat in the Second World War is written in blood, and the shedding of blood in those early months of battle led to a reinforcement crisis in Canadian infantry battalions, including the Argylls.

From 26 July to 6 December 1944, the losses were: 151 killed in action (or died of wounds), 458 wounded, and 32 prisoners of war, for a total of 641 lost to the battalion, largely in three months (August, September, and October). The figure does not take into account those struck off strength because of sickness or accident. Of the 151 killed, 36 were original Argylls (from mobilization in 1940). After the actions of B and C companies at St-Lambert from 18 to 21 August, LCol Stewart had to amalgamate the two companies into one and, at that, their combined strength was barely more than 70! The casualties suffered after that date at Igoville, Hill 95, Moerbrugge, and Moerkerke exacerbated the situation.

“much needed”

The first reinforcements arrived on 4 September and the number was “sufficient” to revert to four rifle companies rather than three. The 81 reinforcements who appeared on 12 September were “much needed.” Pte Sam Resnick, a reinforcement, remembered “going up [to the Argylls] … after some minimal training.” Pte John “Mac” Mackenzie, helping with the wounded on that day, recalled one of the new drafts taking in the sight of the wounded and saying, “Boy, it’s tough out there.” Mac replied, “No, it’s not a bad day,” and the young man “went green.” When new reinforcements arrived on 6 October, Cpl Harry Ruch recorded in his diary that he, and others, were going back to A Echelon (in the rear) “to train” them.

Training was the key, not only for the fighting proficiency of the battalion, but also for the survival of the reinforcements. Maj Bob Paterson, OC of C Coy, struggled to lead a company short of officers, NCOs, and men. Lt Harold Place, B Coy, said, “It was nothing to go out with a platoon of maybe eight people – which is crazy. Where were the reinforcements? I don’t know.”

“they were just hopeless”

Maj Paterson had “no faith in the reinforcements and that’s what I ended up with practically a company of reinforcements, and they were just hopeless … You’d try and train them, [but] we didn’t have any time.” A/Cpl Burt Eden, B Coy, thought “it always seemed us older guys seemed to get through and the reinforcements didn’t … [they] didn’t have the real training, like. Or maybe it was just their time, I don’t know. But it takes a long time to get to know when you move and when you don’t move and when to put your head up, when not to. Takes a while.”

“exposure to battle … the hardest adjustment”

On 4 November, 20 reinforcements arrived, all Argylls who had been wounded in France, had healed, and were now rejoining the unit. They were not a problem. Three days later, the unit received 10 officers and 120s ORs (other ranks), a huge infusion. Happily, there was little action in November and December. It provided the battalion with time for training and integration at the section and platoon level. Maj Pete MacKenzie thought the latest tranche were “fairly well trained” except for “exposure to battle … the hardest adjustment.” CSM Wilf Stone, A Coy, thought “they [the reinforcements] were the guys that go through the fastest.” MacKenzie’s faith rested with the cadres of experienced NCOs and soldiers to provide the essential leadership to new Argylls and to integrate them. Lt Place, for his part, talked about the platoon and then introduced them to the sergeant or corporal “if he had one.”

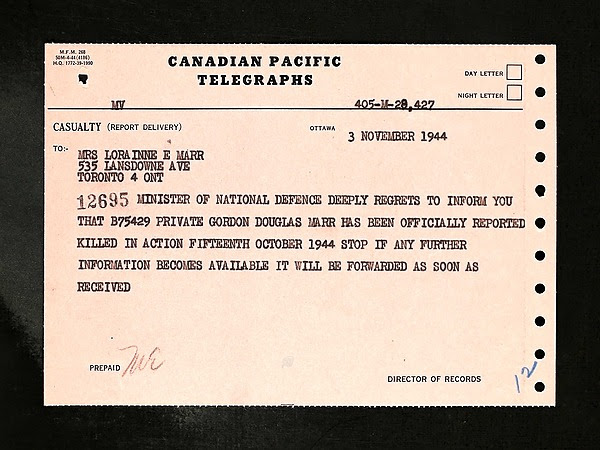

There had been a relative lull in the fighting since 19 September; it began again on 15 October. Ptes Gordon Douglas Marr, Muir J. Marlatt, and William Patrick all joined the Argylls on 12 September as part of the “much needed” tranche of 81; Pte Alexander Nickoloff joined on 28 September. It proved a fateful time for them to become Argylls; all were recent reinforcements; all were killed on 15 October 1944.

“suitable for operational duty o/s”

None of those killed that day expected to be riflemen in an infantry battalion. Bill Patrick, for example, was a “quiet and serious fellow but much concerned about two things (a) to avoid the infantry (b) to be a motor mechanic.” The Personnel Board Officer (3 May 1943) noted: “These facts [good performance on tests and “better than average educational development”] combined with his extreme disinclination for the infantry (having been warned away from it by his father [a Scottish infantry veteran of the Great War] are the reasons for the R.C.A. allocation” as an “automotive driver.” In fact, Patrick hoped to join his brother in Canadian coastal defence. Re-interviewed on 25 April 1944, he was deemed suitable for overseas service with the infantry; on 7 July (still in Canada), he was classified “suitable for operational duty o/s.” Overseas on 19 July, nine days later, after Canadians had been in battle for 22 days, he became “suitable for Gen Services Inf. Fd [forward] Unit.” He suffered three wounds at 1000 hours on the 15th from a machine gun (lumbar spine, abdomen, and left femur). At the field hospital doctors deemed him as a “very poor risk and little prospect of survival, but nothing else waiting and operation seemed only hope.” They operated at 2230; he died six hours later on the 16th. The last note by his doctor reads: “… too much associated injury for survival. Likely hopeless from the start.” He received all the care possible; it wasn’t enough.

Today we tell the story of Privates Alexander Nickoloff and Gordon Douglas Marr: the former an Argyll for just over two weeks, the latter for just over a month. As the saying goes, “once an Argyll, always an Argyll.”

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Pte Alexander Nickoloff (1925–44)

KIA 15 October 1944

“Born in Canada of Macedonian parentage”

Alexander Nickoloff was born in Toronto to James (Joseph) and Evelyn Dimitrove; his father was born in Greece, his mother in “Yugoslavia”; they were “Greek Orthodox.” He completed grade 9 and four months of grade 10 at Central Technical School in Toronto, taking “industrial and machine shop course.” While there, he spent one year and four months in cadets. He left school “for financial reasons.” Prior to enlistment, he worked as a “rug salesman” at Babayan’s Ltd for two years. The firm promised to hire him again after the war, and that was his desire. His “main” language was English; his “other” language was Macedonian. The Nickoloff family was part of Toronto’s small Bulgarian-Macedonian community situated in the east end and centred on St George Macedono-Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox Church.

Alexander enlisted on 14 Dec. 1943 at the age of 18; he was 5’, 6¼”, 132 lb, with brown eyes and black hair. He had astigmatism and a degree of myopia in both eyes, requiring glasses for correction. In fact, he had complained on 16 June 1944 that his “sight [was] poor without glasses.”

“qualities of leadership”

Young Nickoloff made quite an impression on the Personnel Selection Board officer:

“Born in Canada of Macedonian parentage, he is alert and responsive … wellspoken and states he speaks Macedonian fluently. Single, he is the oldest of a family of five and has always lived at home. As a hobby, he has had some success in building model aeroplanes. Keenly interested and active in sports, he has played hockey, baseball and soccer and has been on championship playground teams. Beside reading widely of popular fiction he has a fair knowledge of current events. Interested in young people’s activities, he says he has been in charge of entertainment in an organized group. Dancing, movie and church attendance show him to have a normal social life. His work of continuous employment for one firm shows him to be stable and willing to accept responsibility. With his pleasing personality are combined qualities of leadership.

Of above average ability and good mechanical aptitude he has had experience in driving cars and trucks (chauffeur’s license). These qualifications combined with interest and activity in group games and a keen desire to serve recommend him to Infantry Support where he will become an efficient solider. Will be 19 on 12 May 44.”

“now considered suitable for reinforcement overseas”

On 23 March 1944, at Camp Borden, the army examiner noted that he showed “above average learning ability … it is felt that the [he] will develop well with training as Technical Storeman.” He completed training on 10 July and “is qualified on a Storeman’s course and is now considered suitable for reinforcement overseas.”

“much needed after the casualties”

Nickoloff disembarked in the UK on 9 Aug. 1944 and ceased drawing storeman’s pay the next day (he was now a rifleman); he was in France on 3 September and joined the Argylls nine days later at Sijsele, Belgium, along with 80 other reinforcements “much needed after the casualties.” He was posted to C Coy commanded by the splendid Maj Bob Paterson; the CSM was George “the Great” or “the One-Man Army” Mitchell. Pte Sam Resnick was one of the 81 and, like Nickoloff, posted to C Coy. Sam remembered the day: the Argylls had “just been through a terrible battle [i.e., Moerbrugge] … whoever was there was still in shock. I remember clearly meeting some people that were almost white … if you ever thought for a moment that there was some glamour in what you were going to do, you lost it the first day. The first day.”

“a shell came and hit the house”

Nickoloff fought at Moerkerke, Zelzate, and Sas van Gent and enjoyed the slight lull until the Argylls moved against Watervliet and took it on 14 October. The next day, the rifle companies moved northward. Maj Hugh Maclean wrote that “resistance was weaker everywhere.” But still there was resistance from snipers and German artillery. Pte Art Bridge of C Coy recalled, “We were getting ready to push on up the road and an artillery barrage came down, and I was shooting out a window of the house and a shell came and hit the house right where I was, and it blasted me – my nerves – bad as a result.” Although the war diarist, Lt Claude Bissell, depicted the day as largely uneventful, there were casualties. Maclean wrote “that most of No. 15 Platoon [C Coy] became casualties when a shell landed in their midst.” Four Argylls were killed on the 15th and 12 wounded; all were reinforcements.

“KILLED IN ACTION”

Evelyn Nickoloff received the dreaded, life-altering telegram on 3 November 1944: “MINISTER OF NATIONAL DEFENCE DEEPLY REGRETS TO INFORM YOU THAT B157155 PRIVATE ALEXANDER NICKOLOFF HAS BEEN OFFICIALLY REPORTED KILLED IN ACTION FIFTEENTH OCTOBER 1944 STOP” On the 25th she wrote to the Imperial War Graves Commission (Canadian Agency) in Ottawa: “As yet we have not received and [any] detailed information as to where the casualty took place etc. I was never in close contact with any person in his unit and therefore cannot write to anyone overseas, but am writing to you in hope that you might be able to give me more particulars.” Clearly, young Alexander had sent at least one letter home since joining the Argylls since his mother knew he was an Argyll and in C Coy.

The desire of next-of-kin for more detailed information was common. More often than not, HCapt Charlie Maclean wrote families, as did the company commander or his 2ic and possibly other Argylls. In Nickoloff’s case, it seems that the paperwork for new reinforcements had not yet made its way to F [fighting] echelon. Moreover, the 14/15th marked the bloody start to a three-week period in which the battalion suffered: 44 KIAs and 142 wounded. The Director of Records replied on 14 December 1944, regretting “to inform you that no details are available here relative to the actual circumstances under which Private Nickoloff met his death,” adding that “his remains were buried” on 16 October in a temporary grave on the western outskirts of Oost Eecclo “in the immediate vicinity in which his death occurred.”

“all his future a page now to remain forever blank”

As Capt Sam Chapman later wrote of Argyll death in battle:

“Death is the natural end to the cycle of life. In contrast, the man who falls in battle is far from his family; circumstances dictate that his medical care is less than ideal; his comrades may be there but are so involved with the task at hand that they can give him scant attention. He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank. There is an end but no conclusion.”

“TOO DEARLY LOVED / TO BE FORGOTTEN”

When Alexander’s young sister, Rose, died in 2008 after a long life, her obituary mentioned the older brother who had died so long ago. The family chose the following for the epitaph on his gravestone: “TOO DEARLY LOVED / TO BE FORGOTTEN / MOTHER AND FATHER / SISTERS AND BROTHER.”

Respectfully remembered by an Argyll

Note: Pte Nickoloff’s poppy (with this text) will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Gordon Douglas Marr (1924–44), 1st Bn Argylls

KIA 15 October 1944

“Has good combatant attitude and should make [a] good soldier”

Gordon Douglas Marr was born on 12 May 1924 in Toronto, where he attended Silverthorne Public School, completing grade 7 before leaving at age 13, possibly for financial reasons. His father, William Ferrier Marr (1891-1975), and uncles owned several dairies in Toronto at that time: Marr’s Dairy on Gladstone Avenue and Van Horne, and Brampton Dairy in Toronto. His mother, Ivey Maude Love (1898-1970), ran Silverthorne Dairy in Toronto in the 1930s. Later, she operated Marr’s Tourist Camp in Cumberland Beach, north of Orillia.

“progress and conduct as well as attitude are satisfactory”

Gord had several jobs – farming for two years, a driver salesman in a dairy for three months, and six months operating a woodworking machine in a blind-making factory – before becoming a machinist (trimmer) working on aluminum goods. He served four months with the Grey and Simcoe Foresters in 1940. At his enlistment in Toronto on 15 June 1942, he had a “neat and clean appearance. He is responsive and his progress and conduct as well as attitude are satisfactory.” He “wants to be in the 48th Highlanders with friends.” The descriptions in his personnel summary included: “Intelligence,” “Frank,” “Retiring,” and “Sound.” He was 5’, 9”, 145 lb, with blue eyes and brown hair. Prospects seemed good.

“an ambitious, dependable soldier”

On 31 March 1943, an army examiner noted that he had made “good progress at basic and advanced training” and was now a qualified driver. “Appears much brighter than ‘M’ score indicates, and [he] has become an ambitious, dependable soldier.” There were problems, however. The examiner added that his “relationship with mother has been strained over money matters and a girl, but he is anxious to get home and settle this problem, before proceeding overseas. Has good combatant attitude and should make [a] good soldier.” “His good work as driver i/c warrants further consideration. Has good recommendations from Specialist Coy training officer. Should absorb Automotive Trade Training and become [a] useful Driver Mechanic.”

Marr’s military path seemed set, and there was more. On 5 July 1943, Marr received permission to marry (without a two-month waiting period) as well as a two-week furlough to do so; he married Lorraine (Lolly) Eleanor Lamey (1925–2002) on 13 July 1943 in Ardtrea, Ont. Lolly’s niece Diane recalls, “I was quite young when Aunt Lolly and her first husband appeared at Shaw St [Brenda’s family home in Toronto]. They probably had just eloped and [she] came to introduce her new husband to Poppy [Brenda’s father and Lolly’s brother]. Aunt Lolly was very slight, dark/black hair … he wasn’t too tall in stature. That’s all I can recall but it was quite vivid as he was going off to war.” Like many Argylls, Marr’s record contains a few minor infractions, usually AWOL. As it turned out, Gordy was 20 hours late returning to base from furlough and his marriage; as a result, he was confined to camp for three days plus forfeited pay.

“anxious to get overseas”

In July he completed his automotive trade training “but failed to qualify as a tradesman.” What effect this had on Marr is not known. The officer concluded that he “appears suitable for overseas service as Driver i/c.” While stationed at Camp Borden, he went AWOL again; he was “illegally” absent from 1 to 24 November; he was in Toronto and almost certainly with his wife. She had briefly lived with his parents before taking an apartment. The army held no brief for such a prolonged absence. Court-martialled in January 1944, he was sentenced to 45 days’ detention and forfeiture of pay. His personnel file duly notes, on 24 Feb. 1944, that “this soldier has developed a record since above entry. He is not available for interview at this time as he is in detention until 18 March.” A follow-up interview on 22 March, however, cleared the path for Marr’s overseas service. Marr’s positive attitude, contrition, and evident skills overcame any reservations resulting from his court-martial. He “is anxious to get overseas and explains his misbehaviour on the grounds that he was put on fatigues continuously.” Whatever his explanation, he once again displayed “good combatant attitude,” and that attribute, as well as his list of qualifications, “indicate suitability for overseas service in Infantry … as a Driver Mechanic.”

Pte Marr disembarked in the UK on 8 May 1944. His family experienced tragedy when his older brother, Billy, who was born “deaf” and “mute,” drowned trying to retrieve a boat in July. Gordy made it to France on 2 September, joining the Argylls ten days later, just in time for the fighting at Moerkerke, Zelzate, and Sas van Gent. The life of a reinforcement was a perilous one. At times, their training was lacking; in mid-September there was little time for the battalion to train them further; they had no exposure to battle; and they were joining a unit desperately under strength as a result of casualties. It is likely, albeit uncertain, that Marr was in C Coy, probably 15 Platoon. Maj Bob Paterson commanded C Coy and George Mitchell was the CSM; both were superb.

“Marr and a companion were fighting from a house”

On the 14th LCol Stewart ordered an attack on Watervliet and it succeeded. The next day the companies moved northward, coming under sniper and artillery fire. Marr’s obituary notes that HCapt Charlie Maclean, the battalion’s padre, wrote to Lolly Marr: “The Germans were heavily entrenched on the other side of the canal. The fighting was very severe, but the Canadians drove the enemy back. Marr and a companion were fighting from a house. A shell struck it, killing the occupants immediately.” As Maj Hugh Maclean wrote, most of the day’s casualties resulted from artillery fire on 15 Platoon, C Coy, “when a shell landed in their midst.” Four Argylls died that day; twelve were wounded; all were reinforcements.

“when he was killed it brought back that memory”

What little Marr had, he left to Lolly. According to Marr’s family, his parents, who had married in 1916, divorced at some point. Gordy’s death was the second tragedy for the Marr family. The third came in 1948 when Gordy’s younger sister Joyce died of leukemia. A surviving Marr cousin (b. 1934) remembers Gordy but barely; she has, in fact, a better recollection of his siblings, Billy and Joyce. As for the impact of young Pte Marr’s death on his parents, she does not remember “it being discussed at all.” A second cousin has posted numerous documents and images relating to Gordy Marr’s life on Ancestry.com. For Diane Lamey, “when he was killed it brought back that memory [of meeting Marr and her young newly married aunt at her family’s home]. Never to leave me. Funny how memory is.”

Lolly later remarried and moved to the United States for a time. She did not, however, forget her first love: she named her first son, Douglas, which was Gordy’s middle name.

Respectfully remembered by an Argyll

Note: Pte Marr’s poppy (with this text) will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Between 19 September and 15 October, 11 Argylls were killed in action and 33 were wounded.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Nickoloff’s newspaper obituary photo. Note that he is not wearing Argyll head dress. As a reinforcement with just two weeks in the unit, he may have had a balmoral. He certainly would not have had a glengarry; there is little chance that someone took a photo of him wearing a balmoral.

Pte Nickoloff’s gravestone at Adegem Canadian War Cemetery, between Bruges and Gent, Belgium.

Pte Gordon Douglas Marr, newspaper obituary photograph.

Pte Marr’s parents, William and Ivey (Love) Marr.

Marr family at the dairy (Gordon is possibly the boy at the left).

Marr tourist camp on Lake Couchiching, near Orillia.

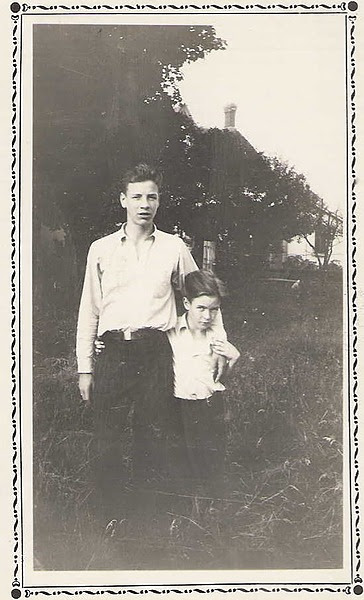

Gordon Douglas Marr as a child, with his older brother William (left).

Telegram announcing the death of Pte Marr.

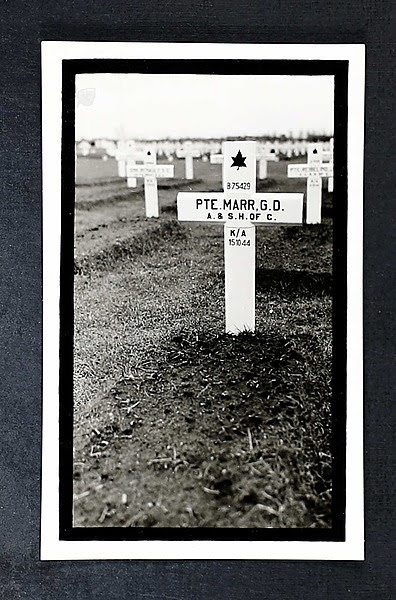

Temporary grave of Pte Marr.