Introduction

Col Alan Earp, OC, a wartime serving officer and an honorary colonel for many, many years – Maj Bill Whiteside, MC, Alan’s wartime company commander told me about 15 years ago that “young Earp” is the best honorary we’ve had since Col Osborne [the Regiment’s honorary colonel in 1940] – supports the idea of the Argyll poppy. He chose his wartime comrade for this poppy.

One of Lt Hugh McCutcheon’s sisters married. Helen Kathleen married Joseph M. Watson of Burlington, Ont. He was still there in 2001–2, but I have not found family past that date.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Lt Hugh John McCutcheon (1919–45), 1st and 2nd Bn Argylls

KIA 28 February 1945

Emigrating from Ireland to Hastings County in 1844, the McCutcheon family moved on to Huron County in the 1850s, Perth County in the late 1880s, and London before the First War; they then moved to Hamilton, where Hugh John was born on 11 August 1919. His father, Walter James McCutcheon (1875-1945), was well-to-do. The family lived at 354 Aberdeen Avenue and attended St Paul’s Presbyterian Church; Hugh went to Westdale Collegiate (opened in 1931) for five years and graduated with his junior matriculation.

Prior to enlistment, Hugh had two years of experience on a farm before working as the officer manager at Consumers’ Lumber Company (owned by Guy Long, father-in-law of Argyll company commander Maj Don “Pappy” Coons) for one year. As for his post-war plans, Hugh hoped to return to “Wholesale Sales of Lumber.” His older brother, Walter James, had served with a local militia artillery battery since 1930 and went overseas in 1940; he had one sister at home (Margaret Isabel) and one married sister living on Beach Boulevard in Hamilton (Helen Kathleen Watson).

“… of exemplary character. Good personality … Shows definite ability to lead and handle men”

Hugh joined the 2nd Bn Argylls on 12 March 1941. When the Argylls were mobilized in 1940, one battalion (the 1st) was designated for overseas service while another (the 2nd) remained in Hamilton. LCol Herb Fearman, an original 91st officer and a 19th Battalion officer decorated for his service in the First World War, commanded the 2nd.

Hugh had ability and recognition came quickly with a promotion six months later. Fearman described him as being “of exemplary character. Good personality and smart appearance on parade. Shows definite ability to lead and handle men.” At enlistment for overseas service on 7 August 1942, Hugh was 5’, 11”, 181 lb, with a fair complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair. He had flat feet, but they were “non rigid,” which meant the condition did not preclude him from active service.

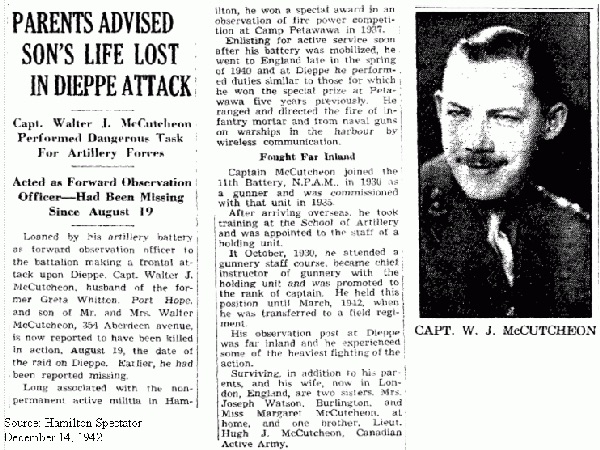

On 19 August 1942, Walter James McCutcheon, Hugh’s 34-year-old brother, was killed while serving as a forward observation officer directing fire support at Dieppe. Hugh qualified Lt on 12 November 1942 and went overseas on 25 March 1943. Serving with the corps defence company, he reached the Argylls on 11 January 1945. After a brief stint at 4 Division’s training school, he took command of 11 Platoon, B Coy, on 30 January; his father had died two days earlier.

Hugh’s brother, Capt Walter J. McCutcheon.

“… elaborate … as if he were conducting a tutorial course in command”

In the aftermath of the battalion’s fighting at Kapelsche Veer in late January, LCol Fred Wigle replaced the beloved Dave Stewart as CO. MGen Chris Vokes had ordered Stewart to undergo a psychiatric examination because of his refusal to commit the Argylls to an unsupported attack at Kapelsche Veer. Wigle, the divisional chief of staff and a Hamiltonian, took over the battalion; he was a staff officer with no experience leading troops in combat.

In the interlude between Kapelsche Veer and the renewal of fighting in the Hochwald Gap in late February, the unit’s time was given over to patrolling. Wigle’s orders for a small patrol were particularly detailed. His approach seemed to the unit’s Intelligence Officer, Lt Claude Bissell, “elaborate … as if he were conducting a tutorial course in command.” It was a far cry from Stewart’s style. As Capt Bob Paterson, 2ic of C Company, recalled of Stewart’s first days with the battalion in September 1943:

I can remember his [Lt-Col Stewart’s] first operation order: verbal, simple, everybody could understand it; the most beautiful thing I ever heard. An idiot could have carried out his plan of attack, or whatever it was, and I thought, “Boy, this is for me.”

On 12 February 1945, the unit war diarist noted:

Two more patrol[s] were scheduled for the balance of the week: … Lt. McCutcheon, whose B Company platoon was to carry out the fighting patrol – known as operation “Sister” – was briefing his platoon during the afternoon. Substantial flare activity was recorded in the evening, while our own activities were confined to preparation for the night’s patrol.

“I was not in the least disappointed that our fighting patrol did not have to do any fighting …”

McCutcheon conducted the successful night-time patrol in conjunction with Lt Alan Earp and his Pioneers across the Maas River “to capture a prisoner.” The night-time patrol was a success and received notable attention not only in the war diary but also in Part II Orders. The war diarist noted:

Lt. McCutcheon and his entire platoon left at 0400 hours. Crossing and landing … were effected without incident, and the patrol proceeded to the dike … leaving one section as a firm base…. Without firing a shot the patrol captured a German – the rear end of a two man roving patrol – and immediately returned to our side of the river. Their prisoner, identified as belonging to the 6th Para Div, unconsciously paid tribute to the smooth work of the patrol, by relating that he succumbed so easily and quickly because he believed one of his comrades was playing a crude practical joke by telling him to put his “Haende Hoch!”

Wigle ordered a report on the McCutcheon/Earp patrol, which became an appendix in Part II Orders. It warrants reproduction in full with its provision of details, down to the section level of a platoon:

War Diary. 13 February 1945. Appendix 10: Report on patrol 12/13 February

1. Embarkation and Crossing

Narrative

The three assault boats were launched in the pond … at 0358 hrs, which was 21 minutes before H hour. They proceeded single-file through the narrow channel leading to the River Maas, thence upstream for a short distance, keeping close to the shore to avoid the current. In order to reach their landing spot … which was almost directly opposite the embarkation point the boats headed out into the river in a N.E. direction. The strong current compelled the boats to follow what was actually a slightly westerly course. Near the north bank the boats were impeded by submerged wire and fence posts, and it took five minutes before they touched down precisely at the landing point agreed on. The boats touched down at H plus 22.

Comments

(a) Boat drill as worked out by B Coy was followed and found very satisfactory.

(b) The current in the river at this point was found to be strongest for a narrow stretch on the south side.

(c) Every man on the patrol had previously had the landing point clearly indicated to him on the ground. This doubtless contributed to the good navigation.

(d) Boats proceeded single-file across the river. The order agreed on could not be maintained because of current, submerged obstacles etc. Each boat load should therefore be prepared to make the initial landing.

(e) The boats left 2 minutes before H hour in order to make their entrance into the river coincidental with the beginning of Sp fire.

2. Landing

The landing was made on the left side of a small inlet. The first section out immediately went to ground on the right side of a dyke road that runs N-S parallel to the inlet. The second section crossed over to the far side of the road and took up a covering position. The third section took up a position roughly between the two preceding sections. The pioneers, in the meantime, moved the boats further up the inlet, and harboured them…. They immediately took up a firm base position, facing mainly towards the right, where it was anticipated that the patrol would get its prisoner most easily.

Comments

(a) It will be noted that ordinary sec tactical drill was used in the landing.

3. Approach to Objective

… The patrol moved off in pl tactical fmn in the order 4, 5, 6 sec. … had revealed mines to the west of the road leading up to the dyke, so the patrol swung out to the east, following the channel that runs N.E. … Two wire fences were encountered on the way up, but presented no serious obstacle. When they reached the point where the channel turns sharply to the east, the patrol cut back towards a house and barn, just south of their objective … 4 sec was left at the house as a covering party, the remaining two secs giving cover until it got into position. The pl comd and runner then went fwd to dyke for preliminary recce and found that a short distance to the west of the dyke-road intersection there were at least 3 rifleman and 2 M.G. posts. He accordingly decided to get his prisoner here instead of to the east, as originally intended, and came back to pass on the new orders to 5 and 6 secs. 5 sec was to provide a secondary firm base immediately ahead on the dyke while 6 sec moved through to get the prisoner.

Comments

(a) The route followed was determined by consultation with OPTS and the Scout pl comd, who had recced the area on the previous night. The infm given was found to be accurate. The route followed natural and artificial landmarks and was firmly fixed in the mind of each member of the patrol. Flooding had changed the appearance of the ground in spots, but a brief consultation between the pl comd and the leading sec comd speedily resolved difficulties.

(b) Drill for wire cutting was as follows: the third man in each sec had a pair of wire cutters. On reaching a wire obstacle, the first two men climbed over and took up covering posn on the far side while the wire was being cut.

(c) There was some confusion while the 3 secs reached the vicinity of the objective and began to take up their final posn. This is the crucial point in the patrol: each sec must keep together and know exactly when to move.

(d) Final brief recce on nearing the objective is important, as it may lead to a change of plan. A simple alternative procedure should be worked out in advance to cover such an eventuality.

4. Action on Reaching Objective

No attack was necessary in this case as an enemy patrol of two men, one on dyke and one on the road to the north of the dyke, conveniently walked by just as 5 sec had got in posn and 6 sec was moving fwd. The enemy apparently had no suspicion of our patrol, in spite of the fact that 6 sect was in full view on the dyke. The enemy on the North side of the dyke was easily taken prisoner by the pl comd, who had some difficulty in persuading him that he was not the victim of a comradely joke.

5. Withdrawal

5 sect with the prisoner withdrew first, covered by 6 sec. When the two sections reached the house just south of the dyke, they went to ground, while 4 sec was withdrawn from its covering posn. The return to the landing place and the return crossing were made without incident, although difficulties in getting over submerged obstacles were encountered.

Comments

(a) There was some delay in picking up the covering section on the return for two reasons: (1) the covering section was not aware that the action had been completed; (2) The covering section was spread out, and the Bren gp could not be contacted easily.

“It was a fighting patrol but we were told to avoid fighting”

The patrol remained a vivid memory in the mind of another young Argyll reinforcement, Private Donald K. MacPherson from Saskatchewan (later Chief Justice of the province’s Court of Queen’s Bench). Young MacPherson was in McCutcheon’s platoon:

It was a fighting patrol but we were told to avoid fighting unless absolutely necessary, and that our primary objective was to capture a prisoner. We had crossed the Maas in a number of those unsteerable canvas boats, and because some wise person (of which there were not too many) had more or less correctly calculated the current of the river, we landed on the German side relatively close to our objective. From there we marched or crawled to the adjoining dike, during which most of us removed our grenades from our various pockets, and hooked them over our belts. We gathered along the base of the dike for a few minutes and then, on the given signal, began crawling up the side of the dike and across the highway on top of the dike, and down the other side. When about half of us had crossed the dike, we heard someone approaching us, walking along the top of the dike. We all froze in our positions, about half on each side, and as I looked across the highway on top of the dike, I noted several dozen grenades that had become unhooked from our belts as we crawled across. I then observed a person who was in uniform, but did not appear to be carrying arms, walking toward us, and as he did so, looking down at the grenades; and as he looked from side to side, I am sure, he saw us lying quietly and unmoving. I assume he was a German officer. However, he kept walking, and when he was out of ear-shot, we completed the crossing of the dike and shortly thereafter succeeded in capturing a prisoner.

Lieut. McCutcheon then ordered us to return to our landing craft and we proceeded to do so. We re-crossed the dike, and in single file (I think there was about 15 of us) we reached a point where we were crawling toward the river’s edge when a whispered command came back from man-to-man that we should hold our positions. I was directly behind Lieut. McCutcheon and I asked him for the reason of the hold up. He told me in calm understandable terms that the leader of our file had encountered a “jump [Schu] mine” and we could not proceed until it was disarmed. This was accomplished after a few moments and we continued to the river’s edge, and after some fruitless searching, we finally found our landing craft, embarked and re-crossed the river.

Because the boats became spread out in the current, after landing on our side, it took some time for us to re-group, and following that we had a fairly long march back to headquarters. We were all pleased the next day to learn that the High Command had extended congratulations to us for a successful patrol. I was not in the least disappointed that our fighting patrol did not have to do any fighting, and in fact, not a shot was fired.

“… one of the most thrilling things I think I ever saw in my life …”

In the days following the patrol, the Argylls continued patrolling and “guessing as to when the Argylls would actually enter Germany and get back ‘into action.’” It would, as it turned out, not take long. On the 22nd February at 0243 hours, LCol Wigle “led the Battalion into Germany. By 0300 hours, the entire Battalion was in the ‘Reich.’” It was, as the war diarist noted, “this moment that we had waited, hoped and struggled for, and morale and optimism within the Battalion were never higher than on this foggy morning.” The Intelligence Officer, Lt Doug Cruthers, called it “one of the most thrilling things I think I ever saw in my life … marching into Germany … with a single piper at the head of the whole … Regiment … and single file down a hill.” “When we hit Germany,” as Lt Earp remembered, “it was a different situation … we raided farmyards and had very fresh steaks,” albeit “very tough ones.”

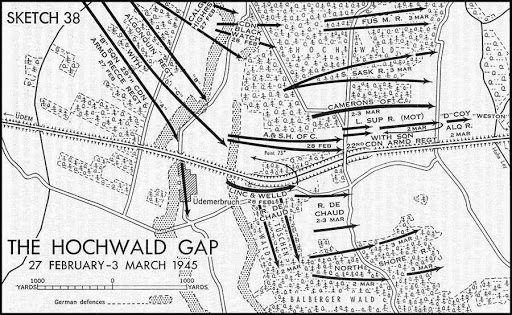

The fighting in the last days of February 1945 in Operation Blockbuster proved tougher, a lot tougher than the steaks. The 10th brigade was split into five battle groups of tanks, infantry, and artillery. The four Argyll rifle companies were divided between Snuff force (C and D) and Jock force (A and B). On the 25th, the “entire Battalion managed to keep quite busy … making last-minute preparations and adjustments for the impending battle.”

Difficulties abounded: rain and more rain; “poorly marked” lanes “deeply rutted,” and carriers with the unit’s vital means of communication, the 19-sets, were stuck in mud and “some had to be permanently abandoned.” As a result, there was “considerable difficulty in maintaining communications during the following days.”

“… the rolling drumfire of serried rows of 25-pounders …”

On the morning of the 26th, a German counter-attack brought the start of the softening up barrage a bit earlier. “No one there is likely to forget the experience, which was simply terrific; single explosions were lost in the rolling drumfire of serried rows of 25-pounders … the southern horizon was continuously lit by the flashes of hits, soon augmented by the heightening glow of many fires.”

“ … really heavy artillery and mortar fire”

In spite of intense German mortar and machine-gun fire, the Argylls took their objectives, along with hundreds of prisoners. The unit also suffered its heaviest losses since late January at Kapelsche Veer: 7 killed in action and 46 wounded. After relief at 2200 hours, the Argylls moved out again at 0800 hours on the 27th but were stopped by “really heavy artillery and mortar fire.” Of four rifle company commanders, only one remained in action by 1700 on the 27th. By comparison to the previous day, casualties were light: 3 killed in action and 8 wounded.

“… a nightmare of terror and blood and sudden death and slow death …”

In the months after the war, Maj Hugh Maclean wrote the unit’s history. The battalion’s struggle in the Hochwald and, in particular, the fighting on the 28th received special notice:

“glorious for the Argylls and also terrible … a nightmare of terror and blood and sudden death and slow death as ‘B’ Company, and in somewhat less measure the other companies, endured on that day, but it was glorious. For at the day’s end, the Hochwald Gap, most viciously defended bastion of the enemy defences in the whole area, was still denied to the Germans, nor did it pass into their hands again.”

The companies advanced again at 0245 hours on the 28th. B Coy was on its objective “at the farther or eastern end of the gap.” All positions were “on the edge of the woods, about half in the woods and half in the open. ‘B’ Company was concentrated around a house, dug in the garden and in front of the building.”

“Lt. McCutcheon, returning from liaising with the tanks, was shot in the head upon his return”

The war diarist outlined B Coy’s predicament. Among its many challenges, communication was fraught with peril and fire support was critical:

The forward elements reached the gap by 0415 hours, encountering concentrated MG fire. Both companies reached their objectives before first light. Captain L.V. Perry’s “B” company captured over 40 PW while Lt. Grose’s “A” company nabbed 30. The enemy was using 88 mm shells and was firing Ack-Ack point-blank into the gap. “C” Company had advanced into the gap on the Southern side, behind “A” Company, while “D” stayed on the northern fringe, behind “B”, on the objective assigned to it.

All the companies, especially the two forward ones, had suffered casualties by the enemy’s incessant shelling and strafing, but the battle of the Hochwald gap did not commence until about 0645 hours, when the enemy began to counter-attack B company in strength. The company, already much reduced in strength, withstood all enemy attempts to dislodge them from their position. The company lost many wounded and killed and some men that were captured, but in return killed 150 Germans, wounded many more and took about 20 PW in addition to the 40 captured in the house that was their objective. Lt. McCutcheon, returning from liaising with the tanks, was shot in the head upon his return. He lived for a few hours, but died before he could be evacuated.

The Argylls sustained heavy losses in the fighting in the Hochwald Gap and B Coy the heaviest: “many wounded and killed.”

“… in his dying last breath … had got through to BHQ and told that we were in a hell of a fix”

Capt Len Perry’s, OC of B Coy, recalled the day vividly:

We had no communication whatsoever, and the Colonel himself couldn’t be blamed for that … he [Wigle] was with A Coy … over in the other corner of the gap. And I was awfully upset that I couldn’t get any artillery support. The only support we got was from one remaining SAR tank which didn’t last very long when it got knocked out. It was about 100 yards back of us, sitting in a little copse, and it did provide tremendous support as long as it lasted … It was to this tank that [Lt] Hughie McCutcheon raced back and I understand in his dying last breath, when he had got through to BHQ and told that we were in a hell of a fix, that we had more Germans around than our own people, and [the enemy had] a lot of tanks as well.

“… a very able and popular officer”

Pte Donald MacPherson, one of B’s small band of survivors, took mild exception to Maj Maclean’s characterization of the survivors’ state as “half-crazed.” MacPherson also provided details about his supposedly wounded platoon commander:

I think the [1953] History [of the Regiment] is inaccurate … where it refers to those of us who survived and were ultimately led out, as being “half-crazed” – we were too exhausted and relieved to be half-crazed.

When relief finally arrived, I learned that Lieutenant McCutcheon had suffered a head wound and was unconscious. He was a very able and popular officer. Four of us managed to get hold of a stretcher, load him on to it and carried him back to the dressing station. With the pre-existing exhaustion, the rough ground and the darkness, it was extremely difficult. To our great distress, on arrival at the dressing station we learned that he was already dead.

“… we didn’t know he was dying …”

Lt Herb Maxwell, commanded another of B Coy’s platoons. He, too, remembered the attempt to save his brother officer:

We carried him [Lt McCutcheon] out, and it took six of us. It takes a lot of men to carry a man out. We must have walked damn near two miles, carrying him on a stretcher. And there was at least one other man on a stretcher that I remember. When we got McCutcheon out to the RAP, just at that time, he died. And I remember the doctor [Capt Doug Bryce] said, “What did you bother bringing him out for? Couldn’t you tell he had stertorous breathing?” … And that didn’t register with me. In fact, I was annoyed, you know. But it was just the way the doctor felt. I suppose he didn’t mean anything at the time. I suppose he thought it was a waste of time to bring a man out who was dying. But we didn’t know he was dying and we had no way of telling if he was going to live or die.

To be fair, Bryce’s Regimental Aid Post had been overwhelmed by casualties over the 26th, 27th, and 28th: 24 KIA and 93 wounded. Lt Alan Earp of the Pioneers remembered “going to the Regimental Aid Post and seeing Maclean, Charlie Maclean, the Padre … and seeing how hard they [Bryce and Maclean] were working and how covered in blood they were.”

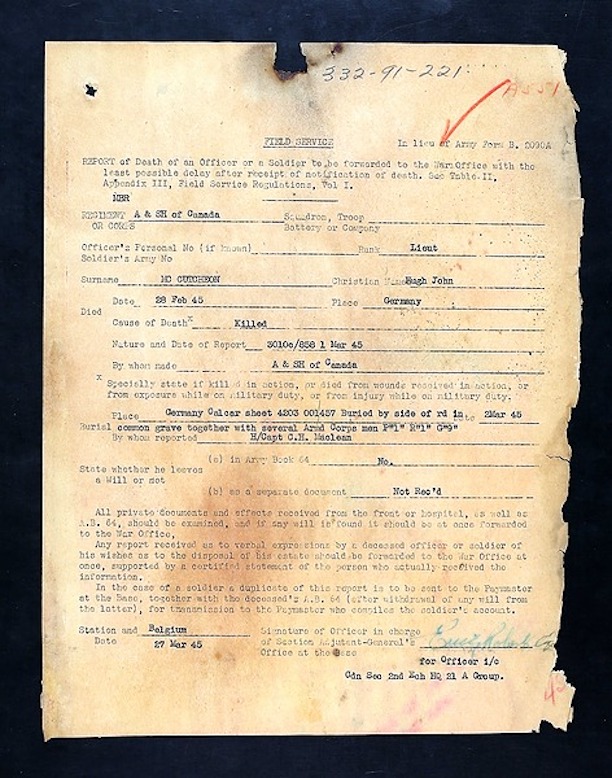

Burial report written by H-Capt C.H. Maclean, 1 March 1945.

B Coy’s struggle had continued over the day and was marked by the heroics of Argylls such as LSgt Clare Huffman, who resolutely led the small band of survivors. Then there was Pte Tom Sayer, who together with one of the Pioneers took an ambulance jeep and evacuated the wounded continuously under great peril. Lt Bill Shields of D Coy thought, “He [Pte Tom Sayer] should have been decorated for that … Three or four times, bringing guys out … Should have got a medal, but didn’t.”

By nightfall B Company was still hanging on to its position, a mere 15 men and some wounded men who could not be evacuated. The men who had beaten off German Infantry, Artillery and armour attacks all day were desperately tired and it was realized that relief had to be despatched. At 1930 hours, Captain Perry returned from the gap and reported at Tac HQ. During the day he had sent runners back on eight different occasions, but not one of the men had managed to reach Tac HQ. When Captain Perry left after last light, the position was slightly quieter, and the company was left in command of L/Sgt Huffman – who had been blinded by enemy action! Captain Perry highly praised the courage and perseverance of the troops under his command, specifically Sgt. Huffman.

“ … he had been a brave and resourceful officer”

Many fell that day. The survivors held on to their memories of Hugh McCutcheon. Maj Maclean wrote: “A comparative newcomer in the Battalion, he had been a brave and resourceful officer.”

From 27 to 28 February 1945, 17 Argylls were killed in action, 40 wounded, and 4 captured.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Warmly remembered by his comrade-in-arms, Lt Alan Earp, in recognition of the Regimental service of Col R.D. Kennedy.

Note: Lt McCutcheon’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Lt Hugh John McCutcheon

354 Aberdeen Avenue, Hamilton (on left).

St Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Hamilton.

Westdale Collegiate, Hamilton.

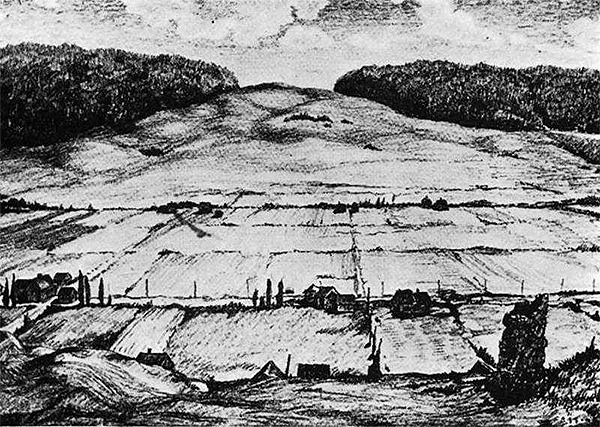

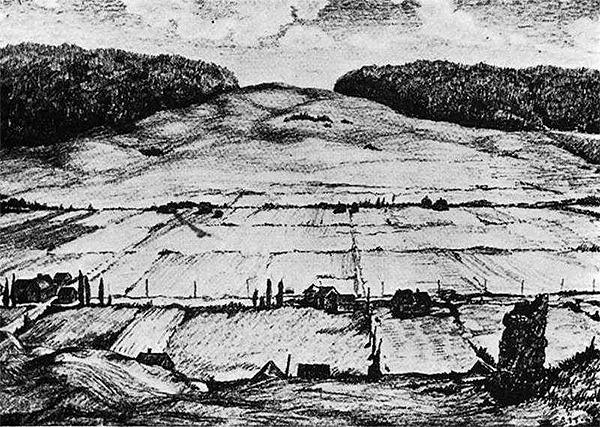

Sketch of Hochwald Gap, 1945.