Pte Joseph Mitchell (B 164333) (1917–45)

Introduction

Pte Joseph Mitchell was nothing more than a name I had encountered over the years. I knew nothing about him or the circumstances of his death. He was, however, an obvious choice for the last Argyll poppy posting for this special project of November 2020 as the Regiment remembers its fallen. Why? Pte Mitchell was the last Argyll to die. He died of wounds sustained in action on 4 May 1945; he succumbed to them two days later. The unit’s first casualties came on 29 July 1944. Here is the history, as Capt Sam Chapman understood, “bought by blood,” the blood of 288 Argylls and the 808 wounded in action. I did not know that Pte Mitchell was one of those men caught up the Canadian political dilemma of conscription and the political compromise that resulted from it, the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) of 1940, a federal act calculated to reduce the clamour in parts of Canada for a more effective and all-encompassing war effort. After a national plebiscite in 1942, the act was amended to allow the government to send conscripts overseas. The NRMA men were castigated as “Zombies” soldiers unwilling to fit overseas unless compelled to do so by statute or severe peer pressure.

“Mackenzie Kings [sic] Commandos’ or better known as Zombies”

Conscription and Zombies were a recurring topic of discussion in the Argylls and across all ranks from 1943 until the end of the war in May 1945. Pte John Booth, Mortar Platoon, was part of the western draft of reinforcements from Camp Shilo, Manitoba, that joined the Argylls at Niagara Camp on 30 June 1943. “At this time,” he wrote, “we were infiltrated by 1% of more of ‘Mackenzie Kings [sic] Commandos’ or better known as Zombies in the hope they would eventually join the active army.” Within the unit, the discussion about conscription and the so-called “Zombies” reached a height in November 1944 after the government’s decision to send a one-time levy of 17,000 NRMA troops to northwest Europe. The high rate of casualties among infantry battalions triggered the reinforcement crisis and the government’s reluctant response.

Battalions such as the Argylls were acutely aware of the problem, which had bedevilled them since the bloody days of August [see Pte Alexander Nickoloff; LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr; ALSgt John Anthony Glavin]. Capt Sam Chapman wrote his wife on 15 November 1944:

If some of the politicians could see a coy of 47 men go into action to do a coy job sometime then they would at least have to realize themselves that political careers are murdering men. If this is democracy is it worth the price? I know my views are extremely localized + narrow and possibly even warped but as far as duty to country goes I think the zombies have thought more clearly than the rest. But one still has to face one’s conscience and anything that is not done for us is accepted with the same shrug of the shoulders that is our only reaction when say our arty drops a couple [of rounds]

short or the tanks get windy and beetle off.

“if they didn’t want to fight, what good were they?”

Pte Roy McDonald, B Company, “can’t recall them being in action … I don’t think anybody wanted them actually. Well, if they didn’t want to fight, what good were they? You want someone who’s going to protect your back.” ASgt Jim Potticarry, Carrier Platoon, stated that “the problem was we were trying to do a job with half the people.” Capt Frank Woods, Paymaster, was unequivocal in his condemnation of the government’s policy:

… it was wrong that many fellows and young men were secure back here [in Canada] when so many others were dying and being wounded and taking it, all the terrible burdens of war over there …

Maj Bob Paterson commanded C Company from September to November 1944. He despaired of the losses, their debilitating effect on an infantry battalion in battle, and the general readiness of reinforcements (in terms of their training):

I took the Company into action three or four times without any officers … We were furious, absolutely furious. Just disgusted … and we wondered what the hell they [the politicians] were doing.

By early December 1944, Capt Chapman, C Company, had detected a change of the Argylls’ attitude to Zombies:

It’s rather amusing how the attitude of the troops to bringing Zombies over has changed. At this point they are not so sure they want them – though they are unanimous in wishing they were back there with a Sten gun to help persuade them to come.

“just a helluva fine soldier” – “these lousy ‘Zombies’”

Pte James Murray, 13 Platoon, C Company, was in a holding unit recovering from wounds suffered on 28 February 1945. He hoped to get back to the Argylls but “never did.” The sergeant-major of the unit said, “You’re not going up again until there isn’t a goddamn conscript in the camp.” And he sent the conscripts.” Capt Len Perry, B Company, spoke glowingly of LSgt Albert Clare Huffman, DCM, and disparagingly of “the bunch of hypocrites” at Camp Ipperwash who had employed “all sorts of terrible tactics to try and make conscripts volunteer to go overseas.” Huffman was an NRMA soldier; in action, it was “not time at all before he was a sergeant – every way – he was just a helluva fine soldier.” Huffman was decorated for his indisputable heroism and gallantry at the Hochwald Gap in late February 1945. On 27 March 1945, Capt Chapman noted that some of the reinforcements had “600,000 numbers still. I thought they would have disguised those guys [the conscripts] a little. I wonder how they’ll do in action.” In May 1945, as the unit prepared for the victory celebration in Berlin, Capt Ron Roscoe, Carrier Platoon, expressed his pleasure that “the boys are old timers and I don’t have to put up with these lousy ‘Zombies.’”

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Pte Joseph Mitchell (B 164333) (1917–45)

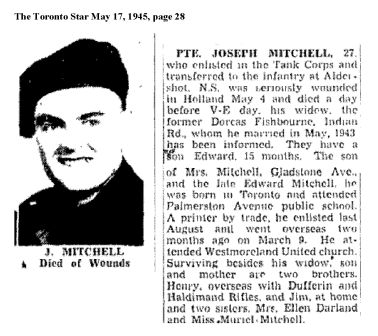

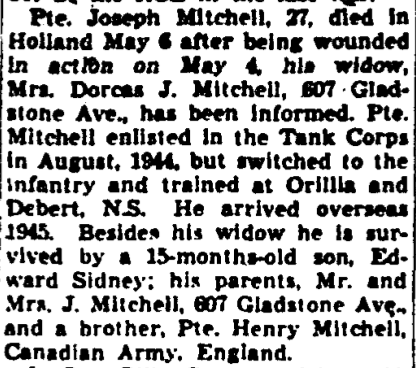

WD 4 May 1945; DW 6 May 1945

Joseph Mitchell was born in Toronto on 21 December 1917, the son of Edward Mitchell and Muriel Beatrice Mitchell (b. 1887); they had married in June 1903 in Toronto. He had two older brothers, one serving overseas, an older sister (living at home with his parents), and a younger married sister. Two other brothers had died within 10 days of their birth. The family resided at 607 Gladstone Avenue in Toronto. Joseph married Dorcas Jean Mitchell (b. 1921) on 24 May 1943 in Toronto; their son, Edward Sidney, was born on 30 January 1944. Joseph Mitchell had left school at 16 and had completed grade 7; he held a trade apprenticeship for printing, which he had completed. The young family lived in a rented a house at 741 Indian Road. Joseph had lived all of his 27 years in Toronto, where he worked as a “Press Feeder (Printers)” for a tool and die maker in Toronto. At enlistment, he had been employed for six years. His employer made no arrangement for Mitchell’s return after his post-war discharge, and, for his part, he expressed no desire to do so; instead, he held out hope for “mechanics.”

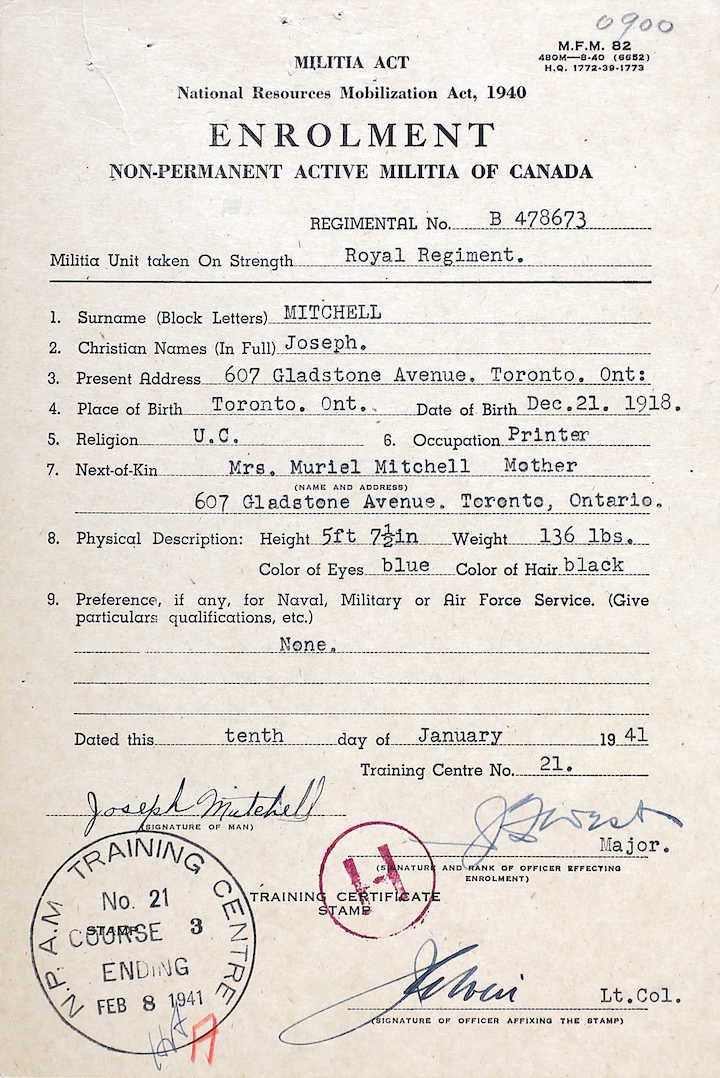

Mitchell enlisted on 21 August 1944. He was registered under the National Resources Mobilization Act (1940) and enrolled on 10 January 1941 with the Royal Regiment in Toronto (B 478673); as to his preference of service arm, he had “none.” His service consisted of 30 days of training in 1941 at Long Branch. He was 5’ 6”, 143 lb, with blue eyes and brown hair. Mitchell suffered a range of medical problems in his young life: bronchitis at 14 and Bright’s disease as well; for the latter he was “sick 6 mos (in Grace Hospital) good recovery.” He also had a “Rheumatic heart 3 yrs. Ago brief disability.”

Mitchell was taken on strength as a trooper at #2 District Depot on 21 August. He transferred to #26 Basic Training Centre in Orillia on 8 September. By this time in the war, soldiers were remustered from the artillery and armoured corps to the infantry, which had suffered the burden of casualties in Italy and in France. Accordingly, on the 22nd he was “re/allocated” from the Canadian Armoured Corps to the Canadian Infantry Corps. He transferred to A14 Canadian Infantry Training Centre on 4 November, ended up in Aldershot Military Hospital on 20 December and was discharged on the 29th (for an unspecified ailment); he went on leave in January 1945 and was taken on strength at No.2 Training Centre on 11 February 1945. He transferred to the Canadian Army Overseas on 25 February and disembarked in the United Kingdom on 5 March 1945, reporting for duty the same day. The next day he went to 7 Canadian Infantry Training Regimen. Pte Mitchell got closer to the battlefield as the war wound down. On 24 April, with the war’s end in sight, he went to the X-4 list of unposted reinforcements; the Argylls took him on strength on 29 April 1945 at Ostercheps, Germany, and he was posted to B Company the next day.

How many Argylls would have to lay down their lives …

The Argylls were still in the thick of the fighting, which was subsiding daily elsewhere. The 27th of April 1945 was, the war diarist observed, an auspicious day:

The day commenced with a particularly pleasant news-item: The Red Army finished the battle of Berlin with the surrender of the remaining 70,000 German troops. With Berlin – the heart and nerve-centre of Germany – in Allied hands, we all realised that the end of the war could not be far distant. How many Argylls would have to lay down their lives before the Germans realised this fact as well, was a question we did not care to discuss or think about.

One wonders if Pte Mitchell harboured the same thoughts privately.

“It’s all madness, a fantasy”

Still, there was a battle to be fought and the battalion received yet another group of reinforcements to bring its rifle companies back up to “a fighting strength of 90 men each. “At brigade, Maj Bob Paterson wrote to Phyllis Logie, the wife Maj Alexander Chisholm Logie:

… we are being sporadically shelled, our guns and rockets startle the beautiful spring nights. It’s all madness, a fantasy. Each day we say to-morrow – and yet it’s still to-morrow.

On 30 April 1945, at 0100 hours, the Argylls’ tactical headquarters moved towards Bad Zwischenahn; B Company moved out at first light and met “no opposition on the ground, but were subjected to a fair amount of shelling and mortaring.” By late afternoon, D Company had reached the southern tip of the airport:

For the balance of the day or night there was no change in any of our locations. The battle for the approaches to Bad Zwischenahn had been surprisingly easy, our total casualties amounting to no more than five slightly wounded men.

Late in the day, there was “a strong rain and hailstorm … and the enemy began to shell the road and railway crossing with 88mm airburst.” Moreover, the day brought important news:

The world news on this last day of the month was again gratifying as well as spectacular: The German radio announced the death of Hitler, the Italian partisans announced a very similar fate for Benito Mussolini. Munich fell without a fight to the Americans. With Berlin, Nuremberg and Munich in Allied hands we could, without undue optimism, look forward to the imminently impending unconditional surrender of Germany and the cessation of hostilities!

“heavy shellfire in that advance”

Lt Gordon Purser, 14 Platoon, C Company remembered:

Bad Zwischenahn was a town … which was on a lake by the same name …, and there was heavy shellfire in that advance … Our advance wasn’t really held up greatly, except for the shelling. And I think it was at that time that I heard for the first time a German jet plane …

Cpl John Booth, Mortar Platoon, recalled:

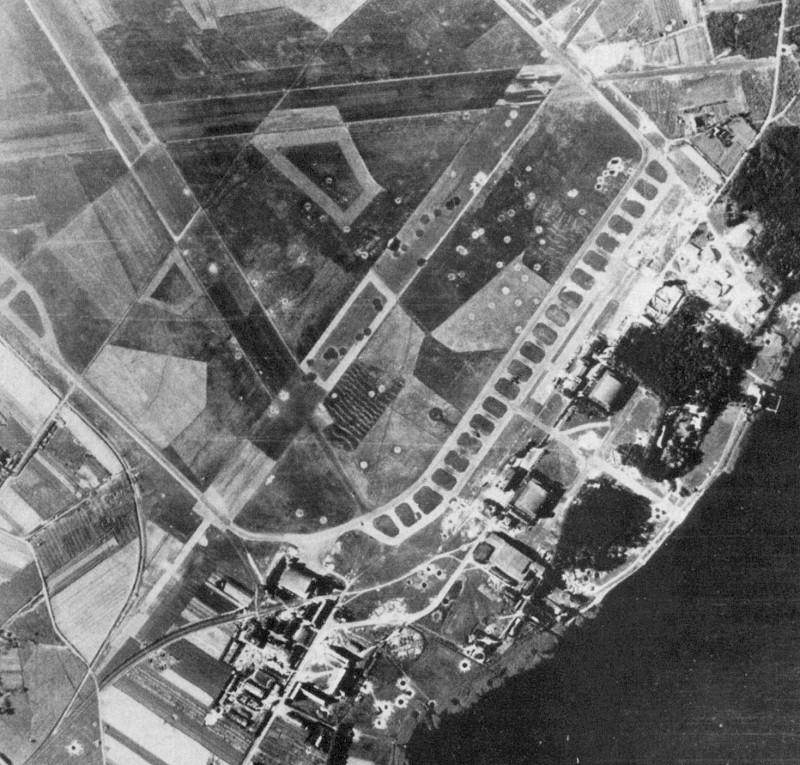

… an attack was teed up for a pincer movement around the Lake, Argylls on the left had the jet airdrome to take + the Lincolns on the right had wooded farm land + a road circling the lake to deal with, by 4.15 on the 30th they had reached their objectives.

We set up our mortars on the tarmac near the edge of the airport close to the bomb shelter, we chisled [sic] holes in the cement for the base plate prongs, it was the solidest footing we had ever found, but risky because we were in the open, we prepared the bombs + sent the men down the shelter [Sgt] Jack Rock & I sent the bombs off rapid fire, the Germans had a good idea where we were because they dropped a mortar bomb in the bush behind us just after we finished the ‘shoot.’

“a marked increase in the enemy’s shelling”

On 1 May 1945, “after twelve hours continuous rain, the weather finally cleared up in the morning and it turned substantially milder.” Bad Zwischenahn was “completely cut off” and arrangements were made for the town’s surrender. The thought was incomprehensible six months earlier, but “the military situation in Germany warranted such confidence on our part, as the Germans had now definitely reached the stage where they considered discretion the better part of valour. The “pretty little town … promptly surrendered intact and undamaged.” It was immediately declared “Out of Bounds” for “forward elements.” The Argylls resumed their advance by late morning across the airfield with little opposition “on the ground” but “a marked increase in the enemy’s shelling.” The airfield was “liberally sprinkled with bomb craters” and “all its hangers were 100% destroyed.”

The day of 2 May brought more good news of the war’s rapid progress. As for the Argylls, they advanced further along the lake and were shelled in the evening; again, there were more casualties, mainly from sniper fire. Anticipation of the war’s end was high. As Capt Chapman wrote to his wife, “It can’t be long now … I get excited just thinking about it.

“an enemy … who still managed to inflict casualties upon our troops”

The 3rd of May 1945 was “clear and warm.” The “general war news was again of a spectacular nature”:

so spectacular in fact that it became apparent to even the casual observer that the German war-machine was going through its final convulsions before certain death would set in … Despite all that, however, we were faced with the fact that on our own small sector we were faced by an enemy who still had some fight left and who still managed to inflict casualties upon our troops.

Once again, the Argylls were on the move:

The companies set out the same evening to capture Wiefelstede … some three miles North-East of our position, on the main road. We were also advised that the Argylls’ final objective was the village of Spohle … and that we were to reach this objective with as little delay as possible.

Shortly after 2200 hours the companies had consolidated in Wiefelstede, without meeting more than occasional and sporadic SA fire. This activity, as well as occasional enemy mortaring continued throughout the night. The Engineers began to work on the road between Gristede and Wiefelstede, since the road was badly cratered and impassable to most wheeled traffic.

“the Argylls were the ONLY unit in the entire 21st Army Group … still encountering opposition”

In spite of the incontrovertible certainty that the war’s end was imminent, the Argylls found themselves still in the fight. Worse still, they were the only ones in the fight. “At first light,” on 4 May 1945, A and B Companies pushed north towards Spohle. They encountered “20 mm fire as well as AP shells from an enemy SP gun.” They pushed forward, “being subjected to enemy fire every foot of the way.” Still, the Argylls – all four rifle companies – moved forward during the afternoon. “Very little progress was made,” however, “due to heavy and continuous enemy fire. Moreover, there was astonishing announcement from higher formations: “that the Argylls were the ONLY unit in the entire 21st Army Group command who were still encountering opposition, did not help our troops in their predicament.”

“word of the surrender spread”

That evening at 2040 hours came the announcement:

… we had been waiting and hoping for since our first day of action: ALL GERMAN TROOPS IN NORTHERN GERMANY, AS WELL AS THE TROOPS IN HOLLAND, DENMARK AND NORWAY, THE CHANNEL PORTS AND CHANNEL ISLANDS, HAD SURRENDERED UNCONDITIONALLY TO FIELD MARSHAL BERNARD LAW MONTGOMERY’S TWENTY FIRST ARMY GROUP! There was spontaneous and justifiable rejoicing and celebrating as soon as word of the surrender spread among our troops.

It was too late for Pte Wright, who had received grievous gunshot wounds about 1700 hrs during B Company’s advance, 100 minutes before the 1st Battalion’s time in battle finally ended. Unfortunately, he was not alone. It was also too late for Sgt Robert W. Johnson, who had died of his wounds on the 5th; or for LCpl Romeo Ciiccone or Pte Ubald W. Laneville, killed in action on the 4th; or the 9 Argylls wounded that day.

“that the enemy facing us had no way of knowing that his commanders had surrendered”

The most pressing situation for the commanding officer was to prevent further casualties. For Lt-Col Albert Coffin, the “main problem at the present seemed to be the fact that the enemy facing us had no way of knowing that his commanders had surrendered.” Accordingly, he ordered “all companies … to abandon their positions, using as much … ammunition as possible to forestall an enemy attack, withdraw into the town of Wiefelstede and firm up there for the night.” “Throughout the night,” the war diarist noted, “we were practically counting the minutes ’til 0800 hrs 5 May 45 when the unconditional surrender became effective!”

For Cpl John Booth, Mortar Platoon, it was almost too much to bear:

… on May 4th … [the Argylls] kept going until small arms fire + the crash of an S.P. stopped them, an attack was planned for 10 o’clock that night. The troops were in a disgruntled mood for they knew 2nd Division was in Oldenburg after no fighting, Berlin had been captured + the Poles were racing to Willemshaven [sic] + that of all the 4 Division the Argylls + Lake Superiors were the only units in contact, it was bitter to know they had already lost 15 men, two of them being killed + that they still had a fight before them, it seemed a terrible breach of justice that they should be the ones to go on + to probably die at the hands of a rabble of fifth rate marines, boys + embittered fanatics. Twenty minutes before H. hour a message trickled through to the forward companies. “Withdraw all forward troops + take up defensive positions well out of contact.”

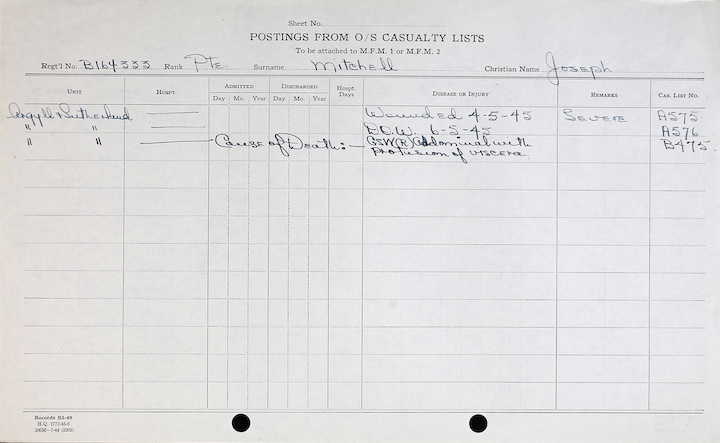

“The cause of death was a “GSW(R) Abdominal with protrusion of viscera”

As Pte Harold Reid, Carrier Platoon, recalled bitterly, “the fighting went on that night. In fact, a few guys got killed that night – didn’t just stop like that.” Lt Bill Shields, D Company, never forgot” the last casualty was lying out in the front yard that had been hit and died [Ciccone or Lanneville] …” And “a few people coming in had been wounded …”

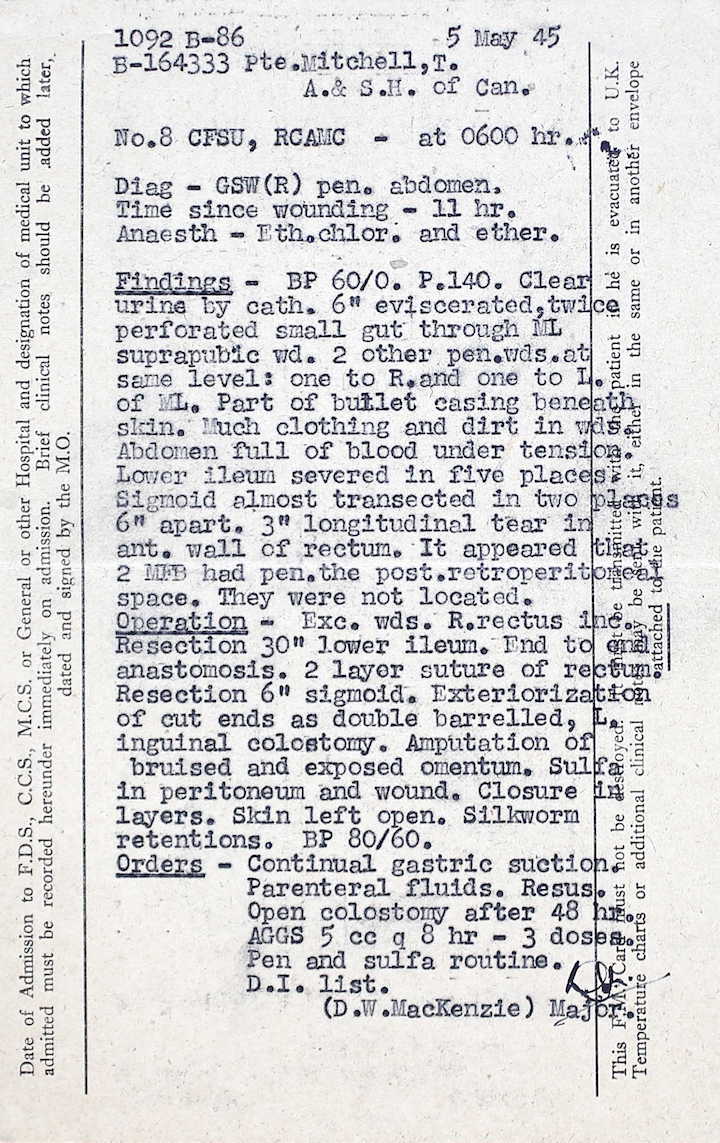

Pte Mitchell was taken to 12 Canadian Field Ambulance the same day, and admitted to No. 8 Canadian Field Surgery Unit at 0600 hours on 5 May. The wounds were serious. The lower portion of his small intestine was “severed in five places”; the sigmoid, or last part of the large intestine leading into the rectum, “almost transected in two places 6” apart”; and a “3” longitudinal tear in the ant. Wall of rectum.” Moreover, he had “part of bullet casing beneath skin. Much clothing and dirt in wds.” The surgeons performed a number of procedures on Pte Mitchell. It was not enough, however, and he died on the 6th. The cause of death was a “GSW(R) Abdominal with protrusion of viscera.”

Postings from O/S Casualty Lists: Pte Joseph Mitchell.

Postings from O/S Casualty Lists: Pte Joseph Mitchell.

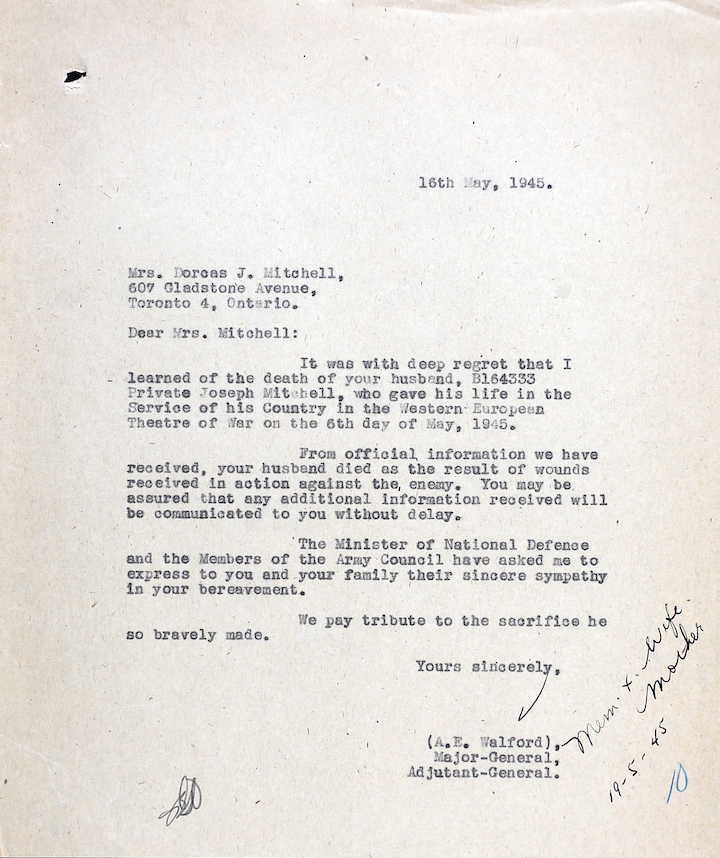

Letter from Adjutant General to Dorcas Mitchell, 16 May 1945.

Letter from Adjutant General to Dorcas Mitchell, 16 May 1945.

Mitchell left little: a leather wallet, a pen and mechanical pencil, a New Testament, a red identity disc, “snapshots and souvenir stamps, a key, 3 “street car tickers,” a membership card, 2 handkerchiefs, 13 cents (Canadian), a black tie, a leather “toilet case,” and some “letters and greeting cards.” His death received the same treatment accorded the 287 Argylls who had preceded him: he was the last recruit to what Capt Claude Bissell called “the shadowy company” of the dead; he was the last man accorded burial rites by HCapt Charlie Maclean, the Argylls’ padre without equal. Mitchell was an NRMA soldier, a Zombie who died as an Argyll after five days with unit in the last hour or so of combat.

Maclean never forgot Mitchell’s situation and the Argylls who died on the 4th, the 5th, and the 6th of May:

… Did I have any thoughts on conscription? … I felt sorry for these young fellows because I don’t think that some of them we got were adequately trained. And I remember some of the officers saying that, too. And I felt that it was terrible that this could happen, that these young people should be sent over and not be fully trained, because unless you’re fully trained, in battle you’re in a far more dangerous situation than you would be if you had training.

And I remember … some of the last casualties that I buried. I think there were four, and I added up their ages [100], and I was shocked at how young they all were. I don’t remember exactly what the figure was at the time, but I really felt, “This is terrible that these young fellows have lost their lives and they are so young.” I remember burying them in a German churchyard – beautiful, lovely churchyard. I felt their lives shouldn’t have been lost at all. The war was too close to ending. It was in the last week of the war … I felt that these kids, they did the best they could and the boys in the Battalion, I thought, felt sorry for them and they tried to lead them along. It seemed a terrible breach of justice that they should be the ones to go on, to probably die.

Maj Bob Paterson wrote the history of the 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade, of which the Argylls were part, after the end of hostilities. He wrote of the Argylls’ movements on 4 May as they:

“… set their course for the more northerly town of Spohle. They kept on driving along the main road, with tanks in support, until a heated flurry of small arms fire, and the periodic crack of an SP, stopped them. They held on until nightfall and a pincer movement involving two companies, one moving on the east and one of the west side of road, white [sic] two companies held, was planned for 10 o’clock that night. The troops were in a disgruntled mood because … they knew that Berlin had long since been captured … and that of all the Division they and the Lake Superiors were the only units in contact. It was bitter to know they had already lost 15 men, two of them killed, and that they still had a fight before them. Everyone was possessed by a certain feel of hopelessness – a realization that the war should be over, that the German Armies were not cohesive fighting formations any longer, [sic] It seemed a terrible breach of justice that they should be the ones to go on, to probably die at the hands of a rabble of fifth rate marines, boys, and embittered, lost fanatics. Twenty minutes before H hour a message finally trickled through to the 18 sets of the forward companies, … [sic] Withdraw all forward troops and take up defensive positions well out of contact.” The The [sic] company commanders thanked God and withdrew. A little later the message of all time came through – a message that will never fail to recall the greatest of many grat [sic] moments in the eventful lives of all who were there — “Cease fire 0800 hrs 5 May 45.”

Pte Joseph Mitchell did not experience the collective relief of Argylls at the end of hostilities. Dorcas Jean Mitchell tended to the administration of his estate. For his grave marker, she chose this inscription:

HE IS NOT DEAD

HE IS JUST ASLEEP

Between 24 April and 6 May 1945, 16 Argylls were killed in action and 57 wounded.

“a history bought by blood” – Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

With respect – an Argyll

Note: Pte Mitchell’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

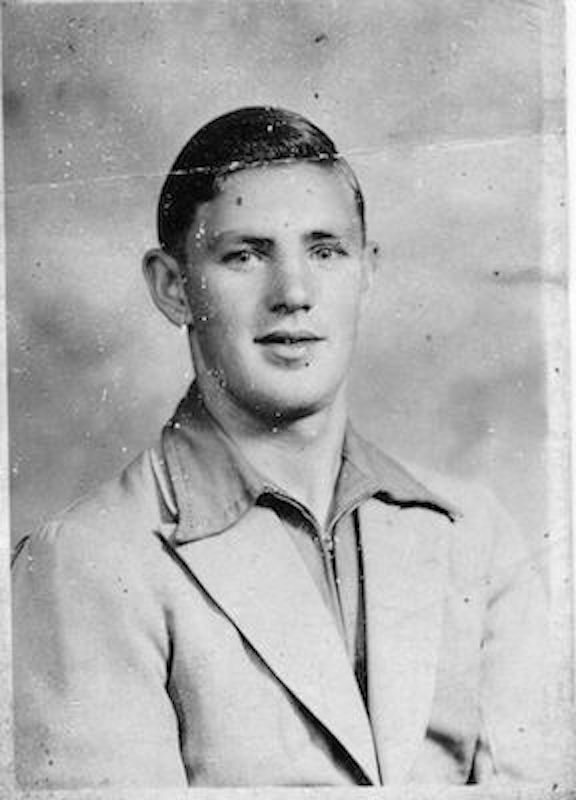

Pte Joseph Mitchell

Pte Joseph Mitchell

Conscription poster.

Conscription poster.

NRMA form, Joseph Mitchell, 10 January 1941.

NRMA form, Joseph Mitchell, 10 January 1941.

Aerial view of airfield, Bad Zwischenahn, 1945.

Aerial view of airfield, Bad Zwischenahn, 1945.

Germans surrender at Bad Zwischenahn, May 1945.

Germans surrender at Bad Zwischenahn, May 1945.

Grave marker, Sgt Robert William Johnson.

Grave marker, Sgt Robert William Johnson.

LCpl Romeo Ciccone.

LCpl Romeo Ciccone.

Pte Ubald William Laneville.

Pte Ubald William Laneville.

Field medical card, Pte Joseph Mitchell.

Field medical card, Pte Joseph Mitchell.

Obituary - Pte Joseph Mitchell.png

Obituary - Pte Joseph Mitchell.png

Grave marker, Pte Joseph Mitchell, Holten Canadian War Cemetery.

Grave marker, Pte Joseph Mitchell, Holten Canadian War Cemetery.

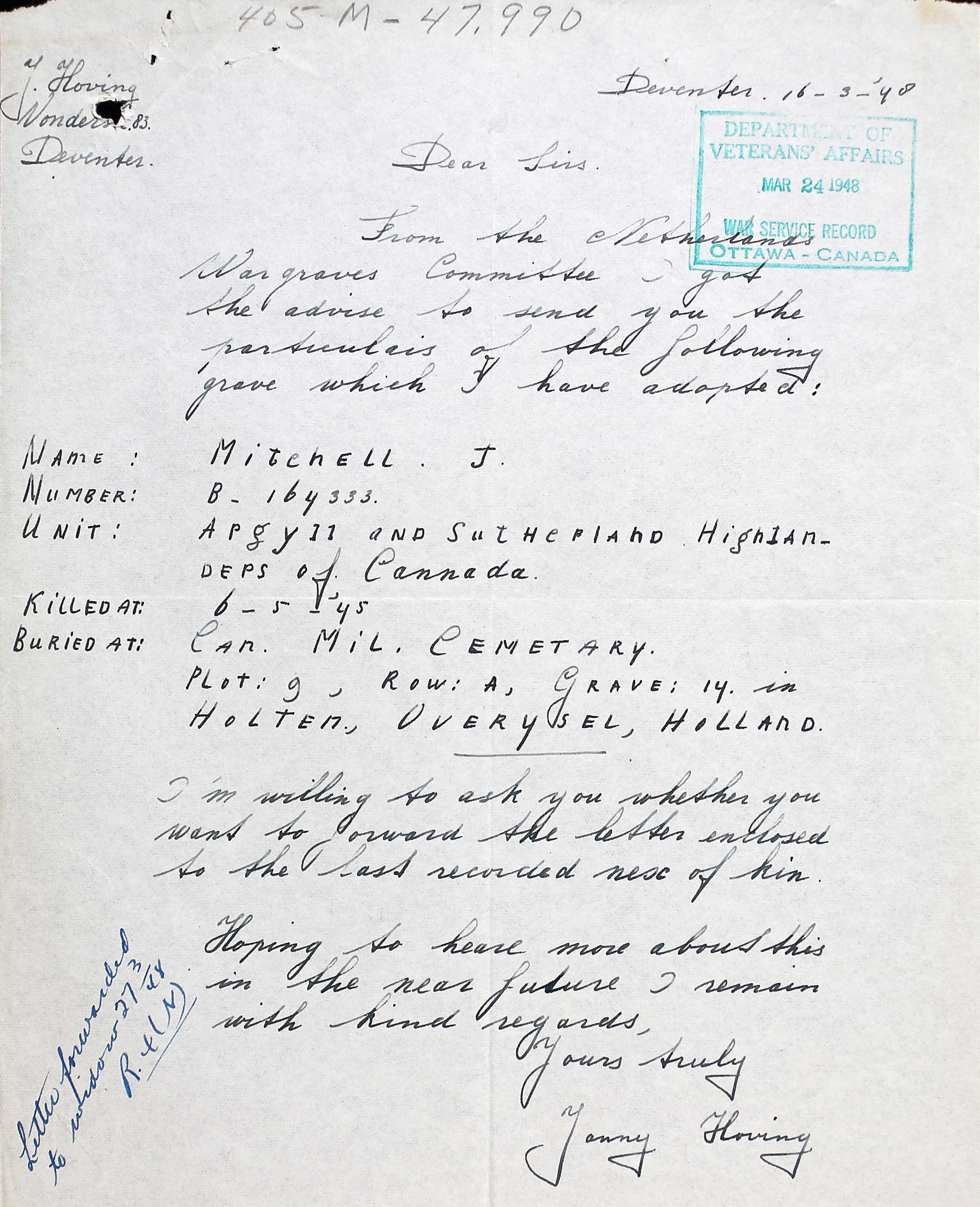

Adoption of grave of Pte J. Mitchell, Holten Canadian War Cemetery, December 1948.

Adoption of grave of Pte J. Mitchell, Holten Canadian War Cemetery, December 1948.