Introduction

The military history of indigenous people in North America is a long one. The Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve is a symbol of the military alliance between the Six Nations and the British during the American Revolution. The life of Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant) is a testament to the military traditions of the Six Nations, who continued to be a military force during the War of 1812 [see John Norton], as did other indigenous people [see Tecumseh]. Indigenous Canadians fought with distinction in both worlds wars. During the First World War, over 300 men from the Six Nations served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force and over 30 were killed in action, including a direct relation of Joseph Brant, Cameron Dee Brant. Several indigenous men served in the 19th Battalion. During the Second World War, members of the Six Nations were in the Argylls from the outset. Sgt Leslie Cecil Brant from Tyendinaga was mentioned in despatches and was awarded the Croix de Guerre 1940 avec Palme by Belgium. Others such as Welby Patterson and Ernest John Howe joined later.

I have known about Welby Patterson for a long time now. Maj Bob Paterson, officer commanding C Company at Moerbrugge, mentioned him to me over 35 years ago; he had recommended him for the Military Medal. Any Argyll recommended by Maj Paterson for a medal is worthy of notice. Welby Patterson has family, and I acknowledge the efforts of my daughter-in-law, Jerica Fraser, in reaching out to them. Welby Patterson wrote his own page in the Argylls’ history and in the history of the Tuscarora of the Six Nations.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Pte Welby Lloyd Patterson, MM (B 139427) (1922–45)

KIA 14 April 1945

Tuscarora

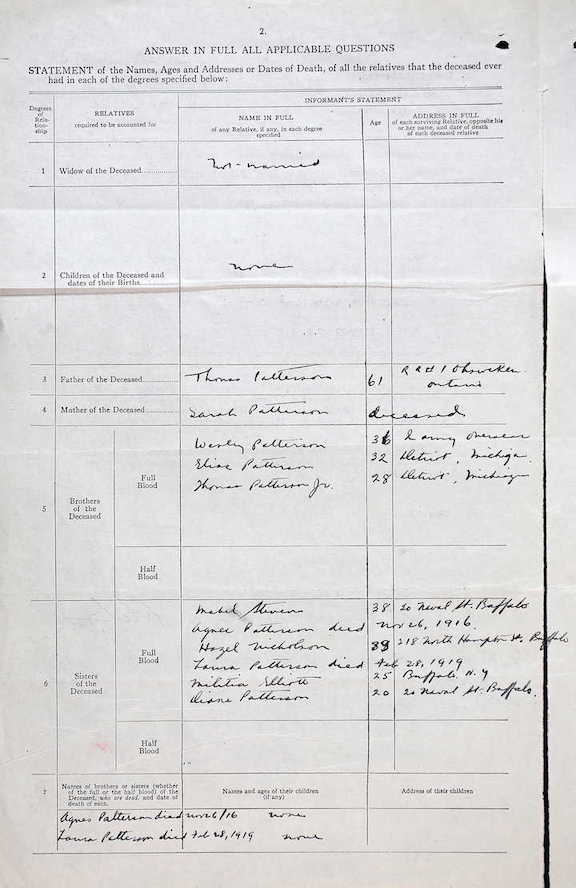

Welby Lloyd Patterson was born on the “Six Nations Indian Reserve” near Brantford on 10 June 1922 to Thomas Patterson (b. 1883– ?) and Sarah Thomas (1887–1936), who had married in 1906 at Ohsweken. Welby was the eighth of their children and grew up on the Six Nations, where he was educated (well educated by all accounts), worked on the family’s mixed farm, played sports – baseball, lacrosse, and hockey – and swam, hunted, and fished. He sang in the church choir at Ohsweken Baptist Church and played the harmonica. Home life was “good” as an army examiner later noted. Patterson spoke Tuscarora and English fluently, and read the latter fluently. Recent studies of indigenous female teachers at the schools on Six Nations and at the Mohawk Institute indicate considerable dedication to, and success at, teaching the curriculum on the one hand while instilling respect for, and preservation of, elements of their culture on the other. At enlistment, Welby’s eldest brother, Wesley Patterson, was overseas while his other two brothers lived in Detroit, Michigan; his four sisters all lived in Buffalo; two other sisters had died in childhood (one in 1916, the other in 1919).

Cpl Welby Lloyd Patterson’s family.

“Adventure”

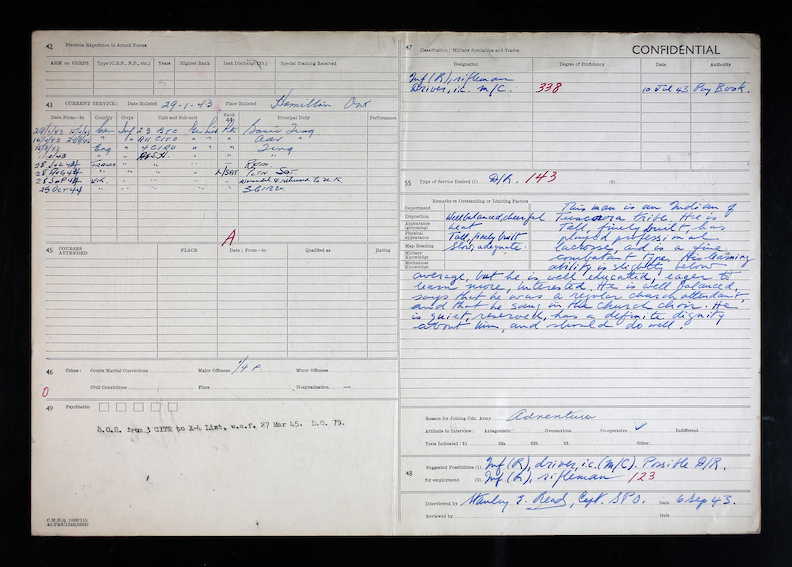

Welby Patterson enlisted in Hamilton on 29 January 1943. He was 5’ 11,” 163 lb, with brown eyes and hair, and “good” development. At enlistment, he lived in Ohsweken; his father was his next of kin and he lived in Buffalo, New York. Welby had completed grade 10 and “Part of Grade XI” at an “urban” school and left when he was 18. He worked for a year on his father’s farm on the reserve from 1940 to 1941, receiving a weekly “allowance.” He was then employed as an iron worker at Republic Steel in Buffalo, where he earned $90 weekly. He had no previous military experience. Patterson made a powerful impression upon most army interviewers and personnel selection officers. He had one year of a trade apprenticeship for steel work. There were no guarantees by his employer to post-discharge employment and, as for Patterson, on one form he indicated his post-war hope to be a welder; on a latter one, he attached his wish to farming. Later, when asked why he enlisted, the reply was one word – “Adventure.”

“a smiling, good-natured manner, coupled with a good attitude”

On 1 February 1943, the officer wrote:

A quite tall, well-built … Indian recruit of poor complexion. He is of neat appearance, has a smiling, good-natured manner, coupled with a good attitude toward the Service. Recruit has a good educational background received at the Mohawk Reserve, Government School.

He, and his brother own a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Recruit has been riding for a couple of years. He seems to enjoy that type of activity, and has asked for that work in the Service. He appears to have the eagerness and the alertness to make a good motorcyclist. Recruit is of average learning ability. He appears normally stable, and says his habits are moderate. He should make a fairly efficient soldier.

The officer recommended him for “Inf. (Motors) (Possible Motorcyclist.) – Non-tradesman.”

Two days later another officer found him “good natured and obedient” and “possibly good for motorcycle duties.” As to his future, he was less enthusiastic: “he will make an average soldier and will pass with help.”

“a fine combatant type”

Patterson transferred to #23 Basic Training Centre in Newmarket, Ontario, on 2 February 1943 and then to Camp Borden on 16 April. He went AWOL at the end of the month for 93 hours and 10 minutes; his reward was the forfeiture of 8 days’ pay. Granted a 14-day furlough on 14 July 1943, he presumably returned to the Six Nations; he had qualified as a motorcycle driver four days earlier. He was taken on strength to #4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit on 23 August and embarked for overseas on 25 August; he disembarked in the United Kingdom on 1 September. After several months of training, Patterson was “Reinterviewed” on 6 September 1943, having completed his qualifications at #4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU):

This man is an Indian of Tuscorora tribe. He is tall, finely built has played professional lacrosse, and is a fine combatant type. His learning ability is slightly below average, but he is well educated, eager to learn more, interested. He is well balanced, says that he was a regular church attendant, and that he sang in the church choir. He is quiet, reserved, has a definite dignity about him, and should do well.

Confidential assessment, W. L. Patterson, September 1943.

“training here is plenty tough”

The Argylls took Pte Patterson on strength at Riddlesworth Camp in Norfolk on 1 October 1943; the unit had marched there the previous day. Within a week, Patterson was on training schemes in the field at the brigade level. As one of his comrades in C Company wrote home in October, “training here is plenty tough.” Late in the month, there were divisional exercises in “terrible weather.” The emphasis was on conditioning and training at every level. On 1 November, the Argylls moved to quarters near Uckfield in Sussex. Again, there was more training and at an increased tempo. C Coy held a dance on 12 November. The Argylls’ Pipes & Drums led the grand march and music was provided by the band of the Lincoln & Welland Regiment. The dance caught the eye of the ever-observant war diarist: “Femininity was present in quality and quantity, beer inexpensive and reasonably plentiful, the food appetizing and in abundance.”

Patterson had two minor infractions with the Argylls: on 27 November 1943, he used “insubordinate language” to a non-commissioned officer and lost 14 days’ pay; on 15 May 1944, he went AWOL for “23 hours, 1 minute”; the penalty was 1 day of field punishment and the loss of 7 days’ pay; Lt-Col Dave Stewart changed it to 8 days’ pay. His more serious offence occurred earlier: on 10 October 1943, he lost the bolt to his rifle and received 7 days in detention. The Argylls had been on a brigade exercise, made a 5-hour, 20-mile march on the 7th of October, and arrived back in camp on the 9th. There had been a dance that night sponsored by the “unit sergeants” and presumably an inspection on the 10th.

Christmas came and went. The months passed quickly, with the introduction of new weapons (PIATs and Sten guns), a spate of training in the Scottish Highlands (in February 1944), more time on the ranges (C Coy topped all other companies in February’s competition), more training, and reviews by dignitaries, including King George VI, Generals Montgomery and Eisenhower, Canadian brass, and the Canadian prime minister, William Lyon MacKenzie King, who was booed by the troops.

Anticipation among the troops grew after D-Day as they waited their turn and pondered the road ahead. Patterson was in France on the 21st of July and suffered its first soldiers killed in action on the 29th. In early August, the battalion got its first taste of combat and C Company was in the thick of it. Patterson saw action throughout France at Bourguebus, Tilly-la-Campagne, Hill 195, St-Lambert, and Igoville. C Coy had been so decimated by casualties after St-Lambert that Lt-Col Stewart amalgamated it with B Coy to produce one sadly under-strength company.

The reality of battle was nightmarish

The reality of battle was nightmarish, and its consequences – killed, wounded, and POWs – provided considerable challenges to Argyll leadership and the unit’s ability to sustain itself in battle. From 29 July to 7 September, the battalion lost 84 KIA, including 1 major, 6 lieutenants, and 6 NCOs; the wounded numbered 229, including 3 majors, 2 captains, 7 lieutenants, and 11 NCOs; the POWs were 20, including 1 major, 1 captain, and 3 NCOs. The total was 333 struck off strength between 29 July and 7 September, and that number does not include the sick and the injured!

CSM George Mitchell, C Company, kept a private diary (deliberately written in red ink). It records in terse fashion the effect on his company of casualties (killed, wounded, and battle fatigued), continuous fighting, heaving shelling, mortars, snipers, heat, dust, and dysentery. In one month of battle, the company had been all but obliterated; there were few C Company originals left (those who landed in July) at the end of August; Patterson was one of them. The officers and NCOs had taken notice of him and he was promoted acting corporal on 5 September.

“soldiers such as ACpl Welby Patterson”

In the days after Falaise, the Allies pushed into Belgium. Moerbrugge was one of the opening engagements of the Battle of the Scheldt. At the highest level, the situation was changing rapidly after the capture of the port of Antwerp on 4 September (useless because the Germans still controlled the approaches to it by land). Ports were a high priority to supply the rapidly expanding and now rapidly moving Allied force; 4 Div controlled Bruges and was moving south of it to take a bridgehead at Moerbrugge on the Ghent Canal. LCol Dave Stewart had been called away to take over the Bde and command went to the despised 2ic Bill Stockloser. The bridges across the canal had been blown up. Reconnaissance suggested that there would be light resistance across the canal. The battle for Moerbrugge would prove grim and bloody, and would test the battalion, especially C Coy, in a manner it had not yet encountered. Fortunately for C Company, its officer commanding was one of the finest company commanders the Argylls produced, as was his company sergeant-major, George Mitchell. And there were soldiers such as ACpl Welby Patterson.

“the most disorganized canal crossing in the war”

On 8 September 1944, Maj Stockloser ordered an attack on Moerbrugge across the Ghent Canal. The bridge had been blown and there were no assault boats. At the Orders Group, when asked how the companies would get across, Stockloser, to the disdain of all, declared it would be “a crossing of opportunity.” Maj Bob Paterson, C Coy, thought: “Opportunity for whom: the Germans or us?” Maj R.D. “Pete” Mackenzie, D Coy, derided the plan as “the most disorganized canal crossing in the war.” They found an old rowboat and, as Paterson remembered, “we were shelled quite heavily on the approach … and I lost all my stretcher bearers, all my mortar men … I think we lost seventeen or something, and the officers were gone.” C Coy lost 2 officers and 17 men that day by shell-fire before it crossed the Ghent Canal to its objective.

“fragmented and messy … terrible battle”

Moreover, the Argylls faced this challenge seriously under strength. Major reinforcements did not come until the first tranche of 80 arrived on 11 September; reinforcements, and particularly their low quality of training, proved yet another continuing problem through to the winter cessation of hostilities. There were three phases to the battle. It was a “costly, grim, and bloody action” by a cut-off C Coy against a far superior enemy force. 13 Ptn alone lost 25 of 34 soldiers. With no rations or extra ammo, C Coy hung on: a cool OC, a superb CSM, and fine, determined, well-trained soldiers. This “fragmented and messy … terrible battle” showed Argyll leadership, soldiering, and guts at their best.

Moerbrugge had a T-shaped plan with a street leading straight to the canal with houses on either side. It ran into a junction, and there was a small church. A Coy and the Scout Platoon launched a diversion west of the village. C and D Coys would attack the village. The canal was deep and 50 to 100 feet wide (estimates vary). The unit had no assault boats to cross it, with no artillery support. The company commanders were astonished. Paterson remembered that in French novels there were always boats tied up along rivers. Maj R.D. “Pete” Mackenzie, D Coy, found two old, large black punts (without oars). At 1730 hours, one section of D Coy crossed (4 to 7 Argylls per load) to set up a rope for pulling the boats across. The divisional field artillery was short of ammunition and the South Alberta Regiment’s tanks provided indirect fire from their Sherman tanks. The battalion made effective use of the 3” mortars of the mortar platoon, and the 4.2” divisional mortars were also brought into play. D and C came under fire immediately: an 88mm firing right down the street, 20mm flak guns along either side of the street, and mortars. Before it started to cross, C was reduced from 63 to 46 in two hours. At last light, the two companies had crossed. D had lost its OC and C had lost its only junior officer. C had made it (on the left of the main street) to the church; D was held up in houses on the right. The companies dug in and waited for the next day.

“The conduct of the men was beyond all praise”

The situation on the 9th was dire, even desperate. C and D companies took the brunt. Casualties were heavy, and even more so for the Germans. The unit’s war diary entry by Lt Claude T. Bissell depicts the day evocatively:

The situation … remained most serious. Throughout the day, “C” Company especially was in a difficult position, even though the Lincoln and Welland Regiment had crossed in the early hours of the morning and had taken up positions on our right flank. This company had passed through “D” Company, which had been halted just on the edges of the canal, and they were now reduced to S.A. ammunition and grenades. At the same time, they had lost communication with B.H.Q. and were cut off from the other two companies. Repeatedly throughout the day, the enemy attacked their positions, at times in as much as Battalion strength. But the Company hung on and repulsed all attacks with heavy losses to the enemy. To C.S.M. Mitchell goes much of the credit for the success of their stand; he visited company positions, encouraging and exhorting the men; he personally organized and led a party that brought back much needed ammunition and medical supplies, and that, after a fighting patrol sent out for the same purpose, had been beaten back; and he personally broke up several dangerous enemy attacks.

The conduct of the men was beyond all praise, the action of L/Cpl L.A. Webb giving an excellent example: In spite of 20mm and M.M.G. fire directed against his Bren position in the second story of a building, he continued to fire with great coolness and accuracy against the attacking enemy, accounting in a short space, for between fifteen and twenty of them. It had been found impossible, because of heavy enemy mortaring and shell fire to construct the bridge across the canal. Thus the problem of supplies, especially ammunition, became a pressing one. Ammunition parties were organised and the ammunition was taken across the canal by boat.

At 1400 hours, A Company and the Scout Platoon were withdrawn. Lt-Col Stewart returned to the unit an hour later and began at once applying his intellect and intuition to the worsening situation.

As Bissell noted, the worst was yet to come:

Around 1900 … the enemy launched his heaviest, and as it turned out, his final counter-attack. Before, and during, the counter-attack, he covered the whole area from the canal up to B.H.Q. with a heavy carpet of mortar-bombs in an attempt to cut off and isolate our companies and prevent the bringing up of supplies. Once more the engineers were forced to abandon their task. Panicky reports came back that the enemy was infiltrating and crossing the canal to our side. But the attack was beaten back and the enemy’s mortaring began to abate.

“courage, initiative and complete disregard for personal safety”

Maj Paterson always gave unstinting credit to George Mitchell and Argylls such as LCpl Webb; he also singled out LCpl Patterson for considerable praise, praise that would result in a Military Medal. The citation, almost certainly written by Paterson, reads:

On the night of September 9, 1944, an infantry company was among other sub-units of a Canadian infantry brigade which had successfully set a small bridgehead over the canal at Moerbrugge, Belgium. The enemy counter-attacked in great strength, and acting on his own initiative, Cpl. Patterson worked his way through the intense mortar and machine gun fire to a position behind a tree stump, where for three hours he fired with such coolness and devastating accuracy that the enemy was unable to effectively counter-attack the main position. The courage, initiative and complete disregard for personal safety shown by Cpl. Patterson was undoubtedly responsible for the defeat of repeated enemy thrusts at his unit’s position.

“They were going to fight, they were all going to fight”

Maj Paterson gave thanks for the “God given Bren guns” of LCpls Patterson and Webb. C Company held on and the anticipated final attack – they have no ammunition left – never came. Paterson remembered:

I had thirty men, and they were all there. You didn’t have to give any orders. They were going to fight, they were all going to fight … Never thought of [surrendering]. Never entered my mind. Didn’t enter [CSM] Mitchell’s mind. Didn’t enter any of the men’s minds, that I know of … I thought that was the end…. [But] I think I was too exhausted to be afraid … I was fatalistic at that point. I’m no hero. I was no hero at all … there were no heroics in my mind. I was beyond that point.

“G.S.W. [gunshot wound] (HE) [high explosive] rt. Shoulder”

LCpl Patterson was, most certainly, “the strong combatant type.” On 13 September, Paterson promoted him acting lance sergeant. There was more fighting over the remainder of the month. ALSgt Patterson was wounded on 28 September 1944 at Boekhoute: “G.S.W. [gunshot wound] (HE) [high explosive] rt. Shoulder.” He was the only casualty of the day and taken to 17 Canadian General Hospital on 30 September, transferred to 13 Canadian General Hospital on 2 October, and discharged on the 20th. At the time of hospitalization, Patterson reverted to his rank of ACpl. On 15 November, 3 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit took him on strength; from there he went to 7 Training Battalion on 1 December. He received 7 days’ leave on 15 January 1945 with an additional 2 days of personal leave. On 17 February, he was a private again; on 27 March, he joined 3 Canadian Infantry Training Regiment and was back on the continent the next day. Pte Patterson was returning to the Argylls and to the battlefield; he joined them on 7 April 1945 in Klein Fullen, Germany. The battalion would attack Meppen the next day after securing a bridgehead across the Ems Canal. Patterson was back with C Company, which was part of the assault across the Ems at 0600 on the 8th. There was one casualty in the crossing, Capt Malcolm Stewart “Mac” Smith, the OC of Support Company, who was killed in the early morning.

“practically irreplaceable”

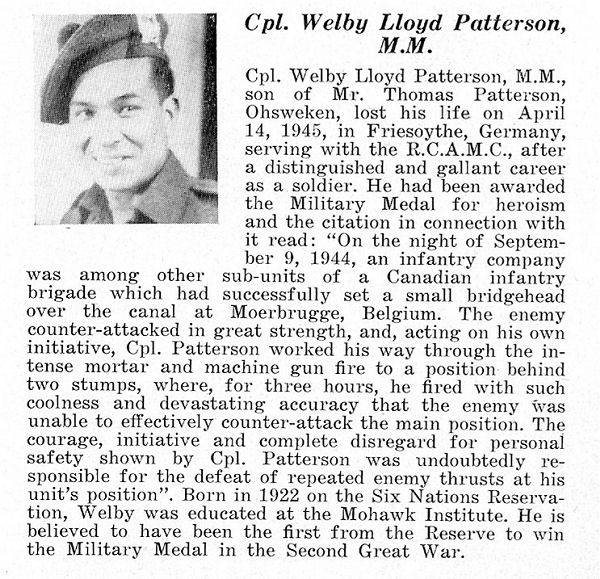

After the capture of Meppen, the Argylls headed towards Friesoythe, a town “dominating miles of surrounding flat and open land.” In front of the town was a creek “known as the Soeste.” Lt-Col Fred Wigle hoped “to place a small plank bridge over the Soeste to enable jeep ambulances at least to pass over …” The battle for Friesoythe is notable for Wigle’s death and the attack on his tactical headquarters. Maj Hugh Maclean wrote the history of the 1st Battalion in the summer of 1945. Of the action at Friesoythe on 14 April 1945, he wrote: ”Argyll casualties in numbers were light, but of the few who were killed one or two were practically irreplaceable.” Maclean mentions only two, and one of them is Wigle, the other Patterson: “Cpl Patterson of ‘C’ Company, who had won the Military Medal at Moerbrugge, was killed by sniper fire while helping to place the plank bridge over the Soeste.” It is a measure of the high regard for Patterson that Maclean ranked his death along the commanding officer’s under the phrase of “practically irreplaceable.”

“a definite dignity about him”

All deaths in battle are tragic, but with the end of the war nigh, these deaths were even more so. H/Capt Charlie Maclean performed a short service and buried Cpl Patterson while an Argyll piper played “Flowers of the Forest.” Welby Patterson left little: a cigarette lighter, an identity disc, a nail file set, a whistle and cord, four souvenir coins, a leather wallet, his service ribbons, some photos, and some letters. He appointed his sister, Carrie Green, executrix of his will; his father was the sole beneficiary; his sister, Hazel Nicholson of Buffalo, had received an assignment from his pay while he was serving. On 28 May 1945, Hazel wrote to the army to find out about his personal items and the settlement of his estate. A Dutch family adopted his permanent grave in Holten Canadian War Cemetery. In that grave rests all of the promise of a “smiling” Tuscarora with a “good-natured manner”: a “quiet, reserved [man] … with a definite dignity about him” and a “combatant” spirit that met the test. His family chose this inscription for his grave marker:

FAR FROM HOME HE DIED

THAT WE MIGHT ENJOY LIFE

NOR SHALL WE FORGET HIM

Between 8 March and 14 April 1945, 9 Argylls were killed in action, 38 wounded, and 2 POWs.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

The Argyll poppy for Cpl Welby Lloyd Patterson, MM, is placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance by Lt Alan Earp, Argyll Pioneer Platoon, who was wounded at Friesoythe on 14 April 1945 – Albainn Gu Brath

Note: The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Mohawk Institute.

Recruitment poster, Second World War.

St-Lambert: SARs and Argylls.

St-Lambert-sur-Dives: SAR tank, Argyll infanteer.

Sherman tank at Moerbrugge.

Ghent Canal, Moerbrugge: the first problem was to secure a crossing.

CSM George Mitchell, C Coy, noted on the back of this picture: “A view of the side of the canal we had to cross to.”

CSM George Mitchell, C Coy, noted on the back, “Coy HQ and a view of the window from which Webb machine-gunned the Jeries when they were counter-attacking.”

The Germans formed up behind this wall to attack C Coy.

Canal, Boekhoute, Netherlands.

Crossing the Ems, 8 April 1945. Lt Alan Earp (in the centre with a pistol on his side) and the Pioneer Platoon ferry vehicles. A view of the crossing several hours after Capt Malcolm “Mac” Smith was shot and killed while standing next to Earp. The hostile shot came from the wood visible on the far side.

Argylls on a Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Wertle, 11 April 1945.

Argylls on Kangaroo, 11 April 1945, Germany.

A line of M14 half-tracks move through Friesoythe, 14 April 1945.

Obituary, Cpl Welby Lloyd Patterson, MM.