By LCol (ret) Tom Compton, CD, BA

Director, Argyll Regimental Museum & Archives

Edited by Katherine Compton, MLIS

L/Sgt James was born in Montreal in 1892 to Walter and Mary James. The family moved to Paris, Ontario, a few years later, where they eventually added his sister Myrtle and brother David. The Jameses lived in a modest cottage house on the edge of what would have been a relatively well-off neighbourhood in Paris at that time (see figure 2).

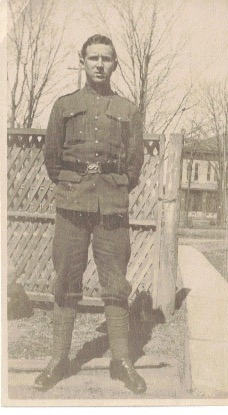

Percy worked as a machinist in one of the Paris factories when the First World War broke out. He enlisted on 11 November 1914 with the 38th Regiment, Dufferin Rifles and was subsequently transferred to the 19th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The Argyll Museum & Archives became aware of L/Sgt Percy James when it received artifacts from Major (retired) Nickles, MMM, of Goderich, Ontario. Percy James’s daughter Willa entrusted a number of items to Maj Nickles, including the helmet Percy wore while overseas, a web belt, a bayonet with scabbard, and, most fortuitously, bundles of personal letters sent to his family from 1914 through to 1919. Percy served almost the entire duration of the war with the 19th Bn, returning to Paris after demobilization in 1919. His letters home give us a unique window into the daily life of one of the soldiers of the 19th Battalion. What follows is an account of Percy’s war from the perspective of his letters. Supplemental information is taken from Dr. David Campbell’s It Can’t Last Forever: The 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War to bring Percy’s comments into context or fill out some details for the reader. The Argyll Museum & Archives are proud to present Percy James’s story as the regiment perpetuates the 19th Bn CEF with the Battle Honours of the 19th emblazoned on our Regimental Colours.

Training in Canada

After enlisting, Private James quickly joined the 19th Battalion at what was Exhibition Camp, currently the Canadian National Exhibition fairgrounds in Toronto. The 19th Battalion were kitted out with uniforms and began the basic training of every soldier, including drill, weapons handling and musketry, bayonet fighting, field craft, and physical training. Prominently featured during those early days were the many route marches to and from rifle ranges in the area of Long Branch along the Lake Ontario shoreline.

Percy James could read and write, but many of his letters reflect a man not used to writing or spelling correctly. This was not uncommon for the era, but what is most striking is the relatively formal way he opens and closes each letter. A letter to his parents dated 5 January 1915 starts “Dear Parents, / Received Fathers letter last week and was pleased to hear from him.” It ends with “Well I think I will close. / I remain / Your Son / H.P. James.”

Percy James is very consistent throughout the war in addressing and closing his correspondence, which adds a certain charm. These letters, it must be remembered, were the only means of communication as there were no telephones or other electronic means available to soldiers other than the odd telegraph. The latter would have been far more expensive than a simple letter, at only two cents postage, whether from within Canada or overseas in the UK or France. A typical letter may have taken two weeks, if lucky, from the time it was posted to the time received, but could be delayed much longer by enemy action or when the Army halted deliveries for operational security reasons.

Pte James and his mates were often given time off from duties while at the Exhibition Camp, and he took advantage of this by exploring the city’s offerings and frequently visiting an aunt and uncle in Toronto prior to embarkation for England.

Departing for England

Percy and the 19th Bn departed Toronto by train on 12 May 1915, arriving in Montreal the next morning. The trains stopped on sidings next to the berth for the passenger liner Scandinavian (figure 5) and the troops were efficiently embarked and given their cabins and bunks. The ship sailed later that morning and arrived in Montreal the next day, but to Percy’s disappointment they were not allowed off to see the city. The ship passed Quebec City that evening, allowing him to see a few lights, but continued out through the St. Lawrence into more open water, with a last glimpse of land as they passed Newfoundland. The crossing took six days, followed by a 12-hour train ride to West Sandling Camp in Shorncliffe, Kent (see figure 6). Percy writes that the camp and accommodations seemed “better than they expected.”

His letter of 22 June 1915 describes the monotonous daily life of drill, range work, physical training, and more drill. Percy also receives his first glimpse of the realities of the war by visiting a convalescent hospital in Camp Sandling, which housed Canadians who suffered single and multiple gunshot wounds at the front. He describes one fellow who survived five separate gunshot wounds to the stomach area. This seems to reassure him as he comments to his father that “some men can stand quite a lot.”

Training in England was a gruelling experience. The battalion was regularly subjected to 30-mile route marches completed in a single day. Whether it is rumour or fact, Percy learns that some soldiers in other battalions fell gravely ill or died while on route marches; however, he is reassured that the officers of the 19th Bn are considered “pretty good” by the troops and that they “think more for their men and look after us better.”

During this period, Percy James is given some leave, during which he visits London but finds it very expensive. He comments that if a man were to live as he wants, he would need quite a bit more money. But then they would likely be dead as a result, presumably from partaking of too much drink.

Boulogne and the Front

Presciently, on 12 July 1915 Percy writes to his father that the battalion expects to depart for France with 12 hours’ notice in the coming days. On the 14th, they leave England, landing in Boulogne on the 15th with the rest of the 2nd Canadian Division. Percy’s comments reflect what the reader comes to learn is his self-deprecating personality: he tells his father he doesn’t want any of his letters to appear in the papers. He also cautions that military censors will be strict in what it is permitted to say about conditions or activities in France, further explaining the lack of detail.

At this point, we learn why his later letters are slim in details about life in the trenches. The combination of his reluctance to talk about himself as anything but a son to his parents and a big brother of his two siblings, along with his healthy respect for military censors, means that the vast majority of his writing relates mundane matters about family members or requests for more underwear and boots to be sent from home. In a letter dated 30 January 1916, he comments to his mother that some troops with little time in the front line like to write home and embellish the real conditions in the trenches, but it is not as bad as they let on. A good friend of Percy and fellow Paris native was Sinclair Knill, who originally enlisted in the 4th Battalion but was soon transferred to the 1st Division Service Train, or rear echelon troops. There are several comments in letters from Percy to his father about Knill; it is apparent that Percy feels Sinclair may be exaggerating in his stories. It is Sinclair who writes about front-line troops, sometimes in different divisions, and the stories seem to find their way into the local Paris newspapers. In contrast, Percy writes only about what he experiences, and when it comes to others, he is quick to say he cannot verify what really happened.

Combat in the Trenches

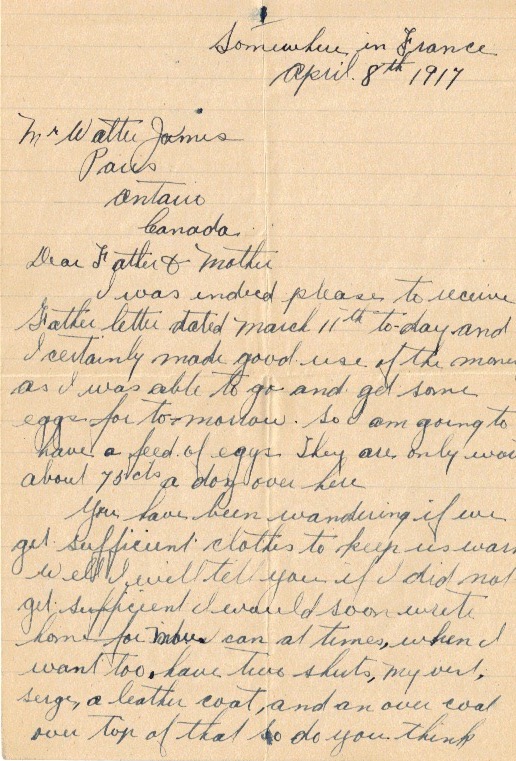

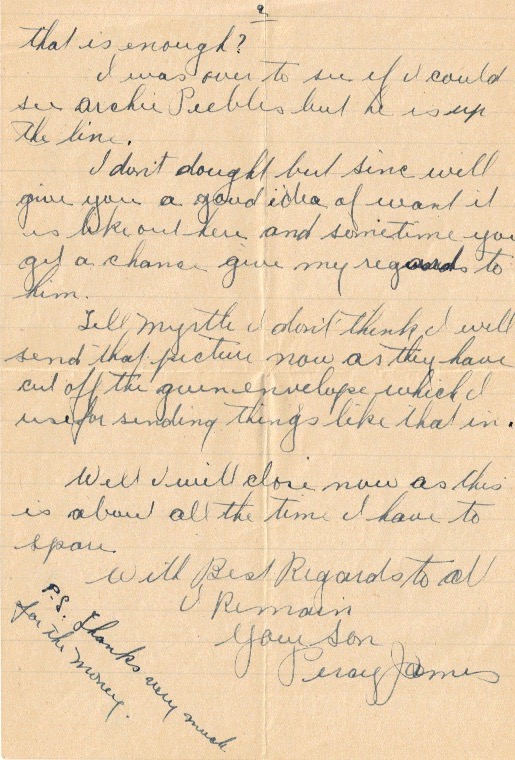

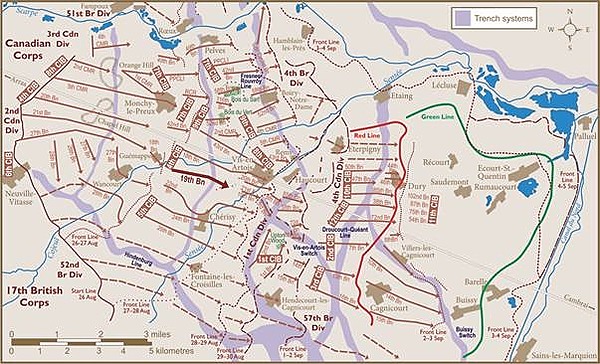

Several of Percy’s letters coincide with significant historical moments for the Canadian Corps. The explicit and implicit details provide fascinating insight into the mind of a soldier when compared with Dr. David Campbell’s research about 19th Bn. The letters dated close to the Canadian Corps’ attack on Vimy are noticeably brief and light on details. On both the 3rd and 8th (see figure 7) of April 1917, Percy maintains a typically breezy tone despite knowing the massive attack was coming soon. It is as if he anticipates this may be his last letter home and he characteristically wants to appear unconcerned and not wishing to upset his family. In an earlier letter on February 14th, he mentions entering the line from communication trenches and going into a cave. Perhaps he wanted to reassure his family of his safety. At that period, we know the 19th Bn was opposite the town of Thelus (see map 1 below) just west of Vimy Ridge, an area honeycombed with deep dugouts and tunnels designed to protect troops in preparation for the April attack.

Figure 7. Letter of 8 April 1917.

Map 1: Map of the Vimy battle.

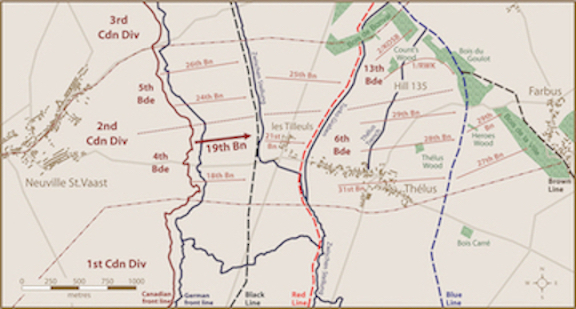

For the most part Percy’s writing is sparse regarding his experiences, and we soon learn that his use of the phrase “too busy to write” typically means he has been engaged in combat. He uses that phrase in a letter to his mother on 15 April 1916. In fact, he had been involved in a dramatic trench raid next to the St. Eloi Crater, led by his platoon commander Lt Hooper. Hooper was leading the “bombing section” on a raid to exploit the gap in the German trenches. However, the ground was so dramatically changed from the explosion of massive mines beneath German trenches that Hooper’s men underestimated how far they had penetrated. Hooper and his men were cut off for two days before they could quietly slink back to their own lines. Hooper was subsequently decorated with a Military Cross for his actions in leading the raid.

Map 2. St Eloi Crater. Courtesy of Dr. Mike Bechtold.

The bombing section was a perilous assignment since those involved were part of the lead assault troops employed in attacks or trench raids. They used early hand grenades or improvised explosives typically known as bombs at that time (see figure 8, No.5 Mills Bomb). Bombers would have experienced vicious, dangerous fighting that often required them to take prisoners alive. Any raid could only have been fraught with risk in trying to disarm Germans attempting to kill the raiding party and not be taken prisoner.

There are rare exceptions to Percy’s natural disinclination to speak in detail of front-line conditions, but they are his personal recollections, not those of others. His comments about what he witnessed during the battle of Hill 70 is one of those exceptions:

“I have seen some barrages and bombardment but that one certainly has it over them all. I was looking back just at the time it started and you could see nothing but flash … you could see a village just behind us all in flames from fire shells.”

He goes on to write how he would clear a bunker of enemy by first throwing in a “smoke bomb” and waiting for the enemy to appear:

“… those who offered fight never had a chance … those who was [sic] peaceful was allowed to go back [to the Canadian rear area] and eat rations.…You never fear anything when you are into things like that. For you follow the crowd and enjoy yourself running around to see what you can pick up.”

In fact, Percy would frequently send home letters referencing a button he had enclosed, taken off a German uniform, or some other form of trench trinket picked up from the Germans, no doubt gathered whilst on a trench raid or attack.

Probably the most important letter sent to his father was written on 16 November 1916, in which Percy underscores his concerns not to alarm his family:

“Mother was saying that I did not mention in my letter what I was doing or what the weather was like. I tell you why I do not. For what you don’t know you don’t have to worry about it and besides the paper says enough to keep you thinking.”

Percy James’s letters were certainly never boastful or disingenuous. His comments above appear to be quite genuine and seem to reflect a man capable of dealing with the confusion and terror of trench warfare. In short, he was a capable fighter who could keep his head in combat, miraculously avoiding becoming a casualty, and he did not seem to complain about the conditions under which he and his mates lived and fought. By this time, he would have seen a lot of combat. The 19th Bn was involved in the Battle of the Somme, which resulted in heavy casualties; the unit strength dropped from 976 to 501. No doubt a lot of Percy’s original battalion friends would have died or fallen wounded during this period.

Percy’s hometown buddy, Sinclair Knills, is quoted in a Paris Star newspaper article dated 7 September 1916, in which he recounts Percy James’s description of a trench raid (possibly the July 29th raid, described below).

“Percy told me about an interesting daylight raid his section of bombers made last week. It was so well planned that they got into the German trench without being noticed. The first German they saw was very busy adjusting a [trench] periscope, quite unaware of their presence, when one of the boys jammed him behind the ear with a grenade. In his excitement he had forgotten to pull the pin, so the bomb did not explode. The “squarehead” [German soldier] was so badly frightened that he ran down the trench squealing like a pig, when they cut loose and cleaned out the trench bringing back about thirty prisoners. Coming from anyone else but Percy this would sound like fiction but you know what he is, so there is no room for any doubt.”

Here we see Percy at the forefront, with a description of his own experience and Sinclair Knills commenting that there is no doubt about the authenticity of the story because Percy is known for his integrity. This story closely matches those of others about the raid, quoted by Dr. Campbell.

Nevertheless, things did not always go as planned, and Canadians were sometimes killed or wounded in these raids. Unfortunately for Percy, an incident on 21 April 1917 led to his losing a German prisoner, likely during a raid, resulting in a court martial and a sentence of 14 days’ Field Punishment No. 1. This often meant being tied to a wagon wheel or post for ostensibly up to two hours a day. Needless to say, his court martial was never mentioned in his letters home.

Daylight trench raids mentioned by Sinclair Knills are an important tactical development pioneered by the 19th Bn and one that is commemorated by the Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) in a monument erected at Pallingbeek, Belgium (see figure 9). No doubt Percy James was part of this very same raid on 29 July 1916. Its purpose was twofold: to confirm the identity of the German troops opposite them; and to locate evidence of enemy equipment and facilities for employing gas along that section of the front. It involved 4 officers and 34 other ranks supported by machine guns and artillery from other 4th Brigade and 2nd Division units. The artillery was particularly effective, as noted in after-action reports, in isolating the German trenches with fire and preventing counter-attacks. In addition, the artillery was used to help rescue Capt Kilmer, who was wounded and lying in a shell hole near the German trenches (see Multiple Medals Following Daylight Trench Raid). Reports noted that approximately 40 to 50 enemy had been killed and the 19th’s raiders confirmed that Wurttemburgers were still holding the line. The design of the trenches and the presence of suspected gas cylinders, trench mortars, and machine guns were also identified.

Boots, Polls, and Rats

Life at the front was not all trench raids and counter-attacks. While Percy spares his family from lengthy and grim narratives of daily life, often saying “not much to write,” he does mention a few aspects of his everyday existence. He frequently enquires about new boots to be sent to him, as the poorly made government-issue boots did not hold up to continual immersion in water and mud. The trench conditions clearly break down his footwear rapidly and frequently. Percy is always very grateful whenever he receives new boots from his father, writing on 8 May 1917 that the latest are “a great comfort.” One highly anticipated parcel with new boots was not received, meaning that the considerable sum spent on another new pair was wasted. It would appear that someone in the rear areas had pinched them, leaving Percy and his father very frustrated about spending money only to have another solder steal from the mail. Despite the perils of enemy trench raids, he does recall rather bemusedly on 18 May 1917 that he lost a parcel from home in a trench raid by “Fritz.” But he is content with the loss of the parcel “as long as I came out on top.”

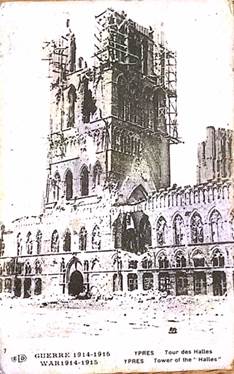

In return, Percy would frequently send home trench trinkets. Besides German buttons, on one occasion he sent his father a British and a German grenade. He also sent a few photos and postcards such as the one below depicting the Cloth Hall in Ypres, which was destroyed by artillery fire (figure 10).

Trench conditions on the Western Front could be gruesome at the best of times. The overpowering stench of decay – the rotting bodies of soldiers and of the poor horses used to haul guns and material – could turn anyone’s stomach. The dead also attracted unwanted visitors. On 27 May 1916, Percy describes rats running over him as he tries to sleep in a dugout. His understated comments tell us he’s more upset about having to burn a precious candle to fend off the rats than the rats themselves.

Later, in September 1917, Percy’s eyes turn skyward when he watches a “Boche” plane shoot down two Allied observation balloons. The German pilot later returns, only to be shot down by Canadian anti-aircraft fire. The writings of many soldiers, including the poems and more prosaic descriptions of the trenches, often focus upward as if to glimpse a life beyond their own squalid subterranean existence.

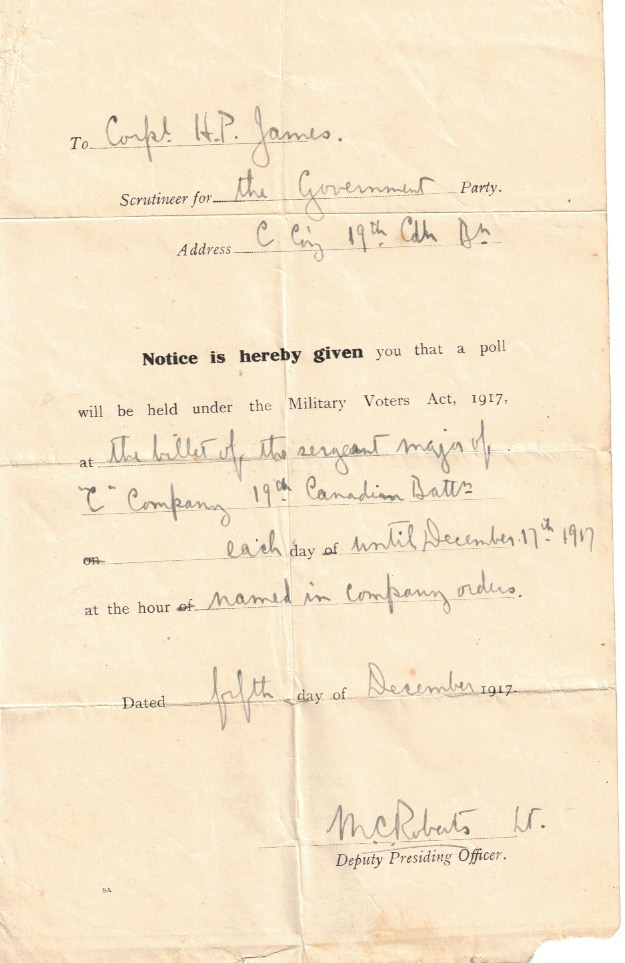

Percy sends home a notice of a federal election poll dated December 1917 (figure 11). The main election issue was conscription. He is clearly upset himself about this issue as he complains in several letters about the men at home enjoying themselves and making lots of money while others are doing their duty for $1.00 a day, exposed to hardships at the front. On 27 June 1917, he expresses his frustration that many francophones did not see the Great War as their war. In frustrated response, he suggests sending soldiers to Quebec to “settle” the matter. Going on leave wasn’t much solace: “The only thing I have against leave is the getting back. For you begin to think why should a few of us fellows be out here taking all we have to when some more young and apparently able body person are going around enjoying themselves the way they do.” In context, Percy’s comments were not uncommon; they reflect the frustration of a soldier doing his duty, not able to understand why others do not support his sense of loyalty to the Crown and his mates.

As mentioned, mail from home was critically important to all soldiers, in particular parcels sent by relatives with food and tobacco. It seems that many made it all the way to Percy unscathed, and he dutifully thanks his mother and his aunt for the cakes, sweets, and numerous socks and underwear. The generosity of his family and others finally becomes a little too much as he writes at Christmas 1917 to not bother sending more food as it goes to waste if not eaten quickly and it is too heavy to “hump” into the trenches.

Although Percy has experienced a lot of combat and many of his comrades have been wounded or killed by August 1917, he is far too valuable to be pulled off the line. Instead, he is given the job of sniper. He enjoys this role, mentioning in a letter that he “works” during the day but sleeps at night, no doubt a welcome relief from standing sentry through the night. Nevertheless, the job of a sniper would have been very dangerous as both sides employed a variety of methods to defeat sniping, including counter-snipers, trench mortars, and artillery.

The 100 Days

Percy writes home in June 1918 that he has been appointed acting corporal without pay and appointed armourer. He says he is fine with not being confirmed in his position as a substantive corporal would be expected to be in the front line – in other words, leading troops in combat. In a subsequent note, he says he could have previously sought promotion to NCO but didn’t want to be one of those “ranting in front of the others.” Avoiding the substantive rank of corporal is a fortuitous break for Percy since, as an armourer, he would not normally be employed in the assaulting rifle companies, thus avoiding becoming one of the many casualties in the closing months of the war.

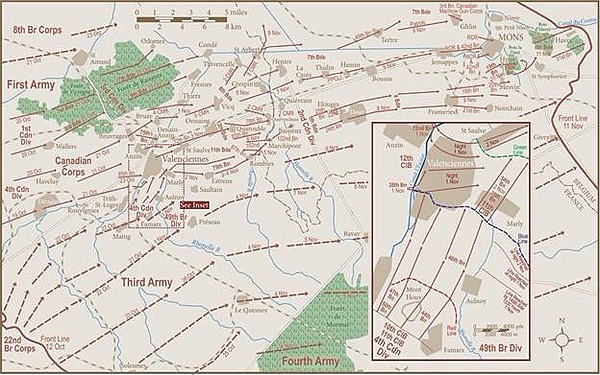

In a letter to his father on 1 August 1918, he suggests that the war news has been good and the “Boche” [Germans] can’t last long. He’s been speaking to captured POWs who thought the Allies could not launch another offensive, but he seems to know that a massive offensive involving the Canadian Corps is about to begin. That offensive has come to be known as the 100 Days Campaign, which launched August 8, the “black day” of the German Army. British, Canadian, and Australian forces smashed the German lines, and by 10 August, Percy has written to his family rather laconically, “I suppose the war news looks better for Father these days.”

On 8 August, the 19th Bn launched its attack on the town of Marcelcave (see figure 12). The Australian 21st Bn on their left flank helped clear a pocket of Germans, which allowed the 19th to sweep through the town, surprising senior German officers in a headquarters dugout. The Canadians moved through the town firing from the hip and clearing out the Germans already stunned by a heavy artillery barrage. The 19th was occasionally helped by other flanking Australian infantry, resulting in gains of two and a half miles from their start line. The cooperation between Australian and Canadian units is an interesting evolution of the Allied forces and their growing flexibility and proficiencies in a new phase of the First World War. The rapid movement of the Canadians was largely the norm in the coming months but so too were the heavy casualties, with the 19th losing 15 officers and 216 other ranks killed, wounded, or missing during fighting for Marcelcave and Fransart on 8 and 16 August respectively.

On the eve of the Battle of Arras, Percy’s August 24th field postcard indicates he’s fine, and in a letter the next day he says he’s seen lots of POWs and, in his characteristic euphemism for combat, states he’s been “very busy.” His family next hears from him September 26, the day before the complex Canadian Corps assault across the Canal du Nord. The 19th Bn was part of the 2nd Canadian Division and therefore in reserve, so he had time to write: “They are certainly going after the enemy these days.… The planes are over bombing tonight so I think I had better stop for tonight and put my light out.” Percy knows the war is drawing to its conclusion as he mentions that Bulgaria is seeking an armistice with the Western Allies. By 3 November, Austria and Turkey have signed an armistice, and he senses that the end for Germany is near, with rumours of armistice negotiations, but most importantly for Percy, he notes he has a comfortable billet for the night.

Map 3. The Battle of Arras. Courtesy of Dr. Mike Bechtold

Map 4. The final advance. Courtesy of Dr. Mike Bechtold.

His mail home is spotty during the 19th’s advance toward Mons, Belgium, but by 2 December the war is over and he points out to his family: “This armistice has certainly got you people excited but still we have got to keep going till they get peace [illegible] that their [sic] is no celebration for us yet: as matter of fact it took from Monday [the 11th] morning till Tuesday [the 12th] night before we were sure that there was an armistice.” Now that hostilities have ceased, he is able to be more candid and identify where he is (Mormont, Belgium), and that they are marching with full packs toward Germany at the rate of 15 miles each day. By 15 December, after 20 days of marching, they are in Wolperath, Germany, just east of Bonn. After crossing the Rhine River on 13 December (see figure 13), he proudly tells his family that “their [sic] is moving film taken of it and I am in it.” (That very film of the 19th crossing the Rhine is held at the Argyll Museum & Archives and will be the subject of a later post.) He continues: “We have been greatly surprised in the way [of] the Germany people. We came into the country with the idea that we would have a rough time of it … [but it is] almost as good as Belgium and often they have a meal read[y] for us to sit down. They seem to be pretty well pleased to see us but was very scared the French would come through this way and raise the devil with them.”

Christmas Day 1918 sees Percy and the 19th Bn in Holbach, Germany. He prefers what he describes as his current work of “out post duty” to trench warfare: “The day before Christmas I was put buying and killing chickens.… Christmas dinner was roast pork, chicken, mashed potatoes, apple sauce and pudding which made a pretty nice dinner.” Their meals during this period had a good variety, including venison shot during a “raiding party” in a nearby woods. Percy may have shaken his head in disbelief when speaking to some Germans who knew they were beaten in 1916 but said they had no choice but to keep fighting. No doubt after fighting for four years, Percy and his mates wondered why the Germans had held on so stubbornly. As part of the demobilization process, he was asked what he did before the war and what he wanted to do after the war. He responded that he wished to be a “retired gentleman” [but] “…no doubt I will need more money [than] I have got.”

Return to Canada and Post War

With the war over, the Canadian government faced the monumental task of getting the thousands of Canadian Corps soldiers home, which meant the typical delays of Army bureaucracy. In the meantime, the 19th mounted guards, drilled its soldiers, and maintained fitness training to keep themselves busy, healthy, and out of trouble. Percy managed a 14-day leave to England in March 1919, and upon return he wrote that he was anticipating his return to Canada in a matter of weeks. He reflected on his travels and expressed a desire to see more of the world, perhaps a desire to see a brighter future than that of four years of war. But he is brought back to reality, sadly commenting that he expects many of the men he knew back home are now dead. The 19th Battalion alone had suffered casualties totalling 119 officers and 2,957 other ranks killed, wounded, missing, or injured – the equivalent of three times the unit establishment strength.

Percy was promoted to substantive corporal, vice acting, and appointed a lance sergeant in May 1919. As such, he was newly employed as billeting NCO when the battalion was withdrawn from Germany and moved towards the French coast in anticipation of repatriation. He was very pleased with himself, mentioning to his family that as billeting NCO he always had comfortable quarters. Percy James made his final journey home in May, briefly transiting through Liverpool on 14 May and then to Canada on the troopship SS Caronia (figure 14). His discharge from the Army was quickly processed on 24 May, whereupon he returned to Paris, Ontario.

Percy had difficulty finding work after the war, as did many returning veterans. He moved from town to town in Ontario and briefly into New York State in search of steady employment. In 1923, he married Ida May Billings and they settled in Goderich, Ontario. Ida passed away in 1957 and Percy later moved to Woodstock, Ontario. He died in 1971 at the age of 80 and was buried alongside Ida May in Goderich (see figure 15).

Acknowledgements

The thoughtful donation of the collected personal effects, letters, and images of A/Sgt Percy James were provided by his family through Major (ret) Neal A. Nickles, MMM, CD. Without these letters, this memorial would not be possible and the context of the experiences of the common soldier would not be enriched.

The Paris Museum and Historical Society provided detailed information regarding Percy James’s life after the war as well as his family.

Further Resources

Dr. David Campbell’s book It Can’t Last Forever: The 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War allowed me to tie in Percy James’s letters to the context of the 19th Bn and that of the Canadian Corps operations.

Artefacts of the Argyll Museum and Archives.

Figure 1. Pte Percy James, probably taken in Canada prior to deployment overseas.

Figure 2. Percy James’s family home. Photo probably taken in the 1980s, but the house still exists to this day. Courtesy of Paris Historical Society.

Figure 3. James’s Rifle Sect. Percy James is believed to be the figure standing on the far left, rear rank.

Figure 4. Long Branch Ranges. Image from Toronto Public Library.

Figure 5. The liner Scandinavian, which carried the 19th Battalion to England.

Figure 6. Camp Sandling, Shorncliffe, Kent, UK.

Figure 8. Mills bomb.

Figure 9. ARF Trench Raid Monument, Pallingbeek, Belgium. Photo by the author.

Figure 10. Postcard sent to Percy James’s father depicting the destruction in Ypres, Belgium.

Figure 11. Notice of a poll for the 1917 Canadian federal election.

Figure 12. The ARF monument, commemorating the action at Marcelcave, is located near the start line for the operation. Photo by the author.

Figure 13. 19th Bn CEF crossing the Rhine River, 13 December 1918.

Figure 14. The SS Caronia carried Percy James and thousands of other Canadian soldiers home in 1919.

Figure 15. The headstone of L/Sgt Harold Percival James in Goderich, Ontario. Courtesy of Paris Historical Society.

Figure 16. Bayonet and scabbard from Sgt James’s personal effects.