Introduction

I knew about Jack Prugh through Maj Gord Armstrong, DSO, one of B Coy’s company commanders in battle. It was within the context of his scathing denunciation of Maj Bill Stockloser’s grievous faults as second-in-command of the battalion during Lt-Col Dave Stewart’s absence. Prugh was an obvious choice for a poppy. As luck would have it, I made contact with Capt Jack Prugh’s son Eric, daughter Nina (Prugh) Buchanan, and grandson Dan Choate. They have made a significant contribution to the text honouring Jack Prugh’s sacrifice and, in no small measure, theirs. I thank them for it.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“my heart is so full of love for you”

(Jack to Helene Prugh, 30 March 1944)

“An otherwise uneventful occupation made tragic by the death of Capt. Jack Prugh of ‘D’ Company …”

Jack Prugh was born on 27 June 1916 in Winnipeg, Manitoba, the only child of William Albert Prugh (1893-1971) and Emily Clara Shirley (1890-1918); William remarried in January 1922 to Mayme Hanley (1897- ) after Emily’s death. He was a prosperous man who sold John Deere farm machinery in Brandon, where the family moved in 1922. Jack grew up there and attended Brandon University; he graduated with a BA at the age of 20.

“stylish – outspoken – the golden tenor of the campus – a [Clark] Gable in Lits”

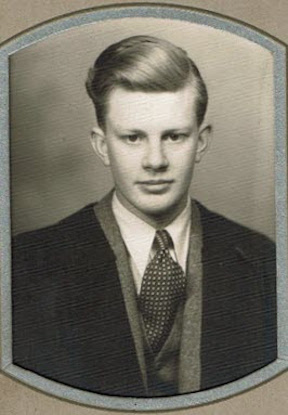

Brandon offered “a Good Curriculum,” “a High Standard of Scholarship,” “Real Teaching,” “Broad Culture,” a “Wholesome Spirit,” a “Christian Ideal,” and “Moderate Costs.” Aside from his studies, Jack served on the staff of The Quill, the student newspaper and the college’s athletic association (he enjoyed swimming), chaired the arts banquet of 1935, and enjoyed theatrics and singing. Academically, he specialized in political economy and economics. The yearbook for his graduating class describes him as “personable and efficient in student enterprises – up-to-date ideas – stylish – outspoken – the golden tenor of the campus – a [Clark] Gable in Lits.”

His voice was like the stars

Had when they sang together.

The stylishness remains apparent in the yearbook images of him in perfectly fitted double-breasted suits with a thick head of hair combed to the side with perfection. Few Canadians from this period had university degrees, and the life of students at Brandon was shielded somewhat from the ravages of the Great Depression. Prugh was on the athletics committee that made a “radical departure” and “in the face of much criticism” changed the traditional field day event “to one of a different type which would emphasize the class spirit more than the individual effort.” The evening was given over to a “snack of hotdogs, coffee and donuts around a blazing fire. A never-to-be-forgotten sing-song was enjoyed by everyone and, to use a well known expression, the evening was brought to a close with Hail Our College and Hippi-Skippy.”

Jack found employment at the John Deere factory in Welland, Ontario, where he met and married Eleanor Helene Collins (1920-1995), the daughter of a Welland pharmacist. They lived there, at 31 Avenue Place, a very modest two-storey duplex. They also owned a piece of property on which they later hoped to build a house.

“might establish own legal practice”

Although the Depression left Jack Prugh unscathed, another event would not. In August 1940, he joined the 2nd Bn of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment as a lieutenant; on 5 July 1942 he enlisted with the 2nd/10th Dragoons as a provisional 2 Lt. John Deere had guaranteed his job after his military service and that was his wish. As for his ambition, he stated that he “might establish own legal practice.” He was 5’, 11”, 134 lb, with blue eyes and blond hair, and a brown birth mark on his right shoulder. The remainder of 1942 was given over to training and courses: he attended the Advanced Driving and Maintenance School in Woodstock, and then completed courses for both wheeled and tracked vehicles, qualifying as a driver for “universal” carriers and wheeled vehicles.

Jack spent his annual leave (11 days) and Christmas leave (5 days) with his wife (from 13 to 28 December 1942). His record reports the birth of his daughter, Nina Eileen Prugh, on 23 January 1943. When she was born, he was in Nova Scotia, stationed primarily at Sydney, where he underwent infantry training and qualified as a lieutenant on 16 July and acting Captain on 1 August. He had 14 days’ furlough in September, which, presumably, he spent with his wife and young daughter

By November he was in Brockville, attached to the “Officers Refresher Wing,” and went overseas on 24 December, disembarking in the UK on 5 January 1944 and reporting for duty the next day. The courses were seemingly endless: the junior officers’ “Pre-Tactical” course from 6 February to 4 March 1944, then a “Battle Tactics” course, a military intelligence course, a company commander’s course, and an “infantry officer wireless” course. During this time, his son, George Albert Eric Prugh, was born on 21 February. With a growing family, promotion brought a needed pay increase: as a 2 Lt, he earned $4.25 daily; as a captain, $6.50.

“longing and endless expressions of love”

From 6 January 1944 until 28 September 1944, Capt Prugh bounced from one reinforcement unit to another (four in total) before joining the Argylls. All the while, he corresponded faithfully with his beloved Helene. Only a handful of their correspondence survives, but it suggests a pattern of longing and endless expressions of love intermingled with the small matters of daily life. On 30 March 1944, Jack wrote letter “No. 65” to Helene:

Again it’s writing time with my family – it’s 8:30 and I’ve just had a nice doze in a comfy chair in the mess – I didn’t actually sleep, I just closed my eyes and rested – it really feels good to do that at the end of the day. After a good supper – when you feel all tired out, and lazy, and good for nothing – not even enough energy to go upstairs to lie down.

“I miss everything about you”

He wondered about his newly acquired habits of eating and sleeping, and how they would jive with hers upon his return. Possibly, he thought, they would:

… just go back to our old way … except that we didn’t have a family then, and only had ourselves to worry about. I’d much rather have the family I think – wouldn’t you? … I can hardly wait to get back and start being a father again. It will be such fun and I’m kind of anxious too to begin being a husband again – I do love you so dearly – my dear dear Helene. Golly but I miss you. I miss everything about you, and everything that we used to do together, and all the fun we had, and we did have fun didn’t we? I have such happy, happy memories of all the days we spent together – and the beautiful evenings too, our walks together in the darkening hours and under the moon, and then our beautiful nights spent in each other’s arms with the sweetness of your breath on my neck, and wisps of your lovely hair tickling my face or neck. It all seems so real, my darling, as though it were only yesterday, and yet the time rolls on, and the months go by, and we are apart. I love to dream of our life together, and to remember all those things, that are so vivid in my mind – those things that are so real now, and will be real again in that tomorrow & may seem now, or is, and we can look back then on this terrible time and be happy and glad for being together once again – even happier, knowing how bleak and how cold our lives have been without the other’s presence – and we can always remember too my dear how really bleak and unhappy we might have been at this time if we had not had the love of one another to keep us alive, and sane and hopeful – That will be a wonderful day – may God speed it on the way – the whole desperate and unhappy world is really ready for it. The world has suffered enough.

Well, honey, lunch will soon be over, and I’ve just felt as good talking to you again, like this. I seem to say much the same thing always, but then it does always boil down into those three little words doesn’t it – and yes my darling, I love you – and my heart is so full of love for you that it is impossible to say just how much – nighty night – my dear – and God bless you.

“you must have quite a time with those little devils”

In his letter of 13 April 1944 (“No. 76”), he wrote:

Well honey, I’m sitting here in my hut on the side of a bed writing on the top of an old brassed top folding table, the light’s awful and the surroundings aren’t very inspiring, but in front of me I have this page, which is just like a mirror or a screen in which I see your face, and beside my elbow is a stack of letters I’ve got the last 2 days from you, 14 in all, I think – quite a haul so it’s just like a real visit with you – I’ve got the biggest kick out of your letters – you must have quite a time with those little devils.

“I’m so much in love with my wife”

The letter was full of details of friends overseas, their various movements, and home life. At the end, he returned to his kids and the small, and much-missed, everyday details of their lives:

Gosh I’d love to see Nina in her corduroy overalls, I’ll bet she’s cute – and Eric’s little fat double chin. O, darling, I miss every little thing as much, and I think it awful that I’m not to be in on those cute little things that our kids do – and I’m so much in love with my wife – my dearest possession – take care of yourself.

“The reinforcement situation was dire”

Having completed CMHQ course #1201 (a month-long course), Jack Prugh arrived in France on 4 September and was posted to the Argylls 24 days later. The battalion had been in almost continuous action from 26 July 1944 to 23 September. The losses were staggering: 104 killed in action, 305 wounded in action, and 32 prisoners of war, for a total of 412 out of an establishment of approximately 800. The number does not include those who left the unit because of sickness, injury, or battle fatigue. The reinforcement situation was dire. LCol Dave Stewart had been forced to collapse B and C Coys into an amalgamated company of approximately 70 soldiers.

The first reinforcements arrived on 4 September and in sufficient numbers to revert to four rifle companies. Another tranche of 81 came on the 12th along with others over the course of the month. There was a critical shortage of officers. From 10 August until the end of September, the Argylls had lost six rifle company commanders to death and wounding. After Prugh’s arrival, two more would be killed and another wounded. Lt Norm Donaldson, A Coy, wrote to his wife on the 28th that “of all the lieutenants who came into France with us, there are only two left.” Each of the four rifle companies had two or three and Support Company had another three; there were 13 altogether on 26 July 1944.

Capt Prugh joined the Argylls on the 28th. The beloved commanding officer, Dave Stewart, was off on a 48-hour leave and the detested 2ic, Maj Bill Stockloser, was acting CO, albeit briefly. Jack’s early days coincided with, as Capt Sam Chapman of C Coy, put it, a “slow tempo” of operations. The days were “cold and wet” but quiet. There was much-needed time for showers, movies, and short-term leaves to Ghent. Dave Stewart was sorting out company commands and even considering rotating company 2ics into OC positions to broaden their range of experience. Capt Prugh had a wide range of training experience and courses, including the company commander’s course; he was an obvious candidate for a company.

By 5 October, Maj John Farmer (former OC of A Coy and wounded in France) was back at the unit. The reality of war struck home when on 10 October 1944 Lt Kerrigan King, C Coy, was killed on a four-man patrol; he had just joined the Argylls days before. By mid-month, the battalion was readying itself for the drive on Essen, Wouwse Plantage, and then Bergen op Zoom. Capt Prugh was not in D Coy before 23 October, the day on which Maj Farmer was wounded again and the only officer left was a lieutenant. The same day Maj Jack Harper suffered battle fatigue and was relieved by Maj R.D. “Pete” MacKenzie; Maj Gord Armstrong, having recovered from an injury suffered before July 1944, rejoined the unit and the stack of bodies awaiting burial by Padre Charlie Maclean, including the two previous OCs of B Coy.

“Jack Prugh’s time had come”

Jack Prugh’s time had come; he took over D Coy and commanded it during the attack on Bergen op Zoom and the deadly crossing of the causeway there. But, once again, LCol Stewart left the battalion (on 26 October for a minor operation), and Maj Stockloser in command. Never liked, Stockloser’s reputation was shattered by his handling of the attack at Moerbrugge, Belgium, in September; company commanders such as Maj Bob Paterson, Maj Jack Harper, and Maj MacKenzie excoriated him. At Bergen op Zoom, his failings emerged yet again; he failed to secure for Armstrong and Prugh essential tank and/or artillery support. Argyll perseverance there is a credit to the company commanders, NCO leadership, and the determination of the small cadres of experienced soldiers in the platoons and companies.

“Captain Prugh’s been killed”

On the “bitter cold and wet” day of 4 November, Prugh led his company into Steenbergen. Maj Armstrong had had a serious row with Stockloser until assured of tank and artillery support for B Coy. A “gentle giant,” as Maj Hugh Maclean described him, Armstrong was a man of principle who raged against Stockloser and the inevitable consequences of poor tactical decisions – death on the battlefield. Gord Armstrong’s comments about the events of the 4th were acid-etched:

Three of the four tanks were knocked out, but we closed the end of the town. Stockloser came up the next day and then I spoke to him in rather pointed terms…. [A/Capt] Jack Prugh [OC, D Coy] was killed there because Stockloser had promised the same thing to him…. Prugh put his attack in on the centre of the town and he came and dropped into where I was, and told me the problems he’s having with Stockloser. I told him what I had done. Jack was just a captain. I guess he didn’t want any black marks. And he left me. And five minutes later [the] signaller … came in and said, “Captain Prugh’s been killed,” and that just added fuel to the hostility that I already had for Stockloser. Totally unnecessary.

“her mother was very ‘bitter’ about what had happened“

Jack Prugh’s war ended that fateful day; another soldier (also a recent reinforcement), Pte Ronald D. McPherson was also killed by a sniper. Jack’s daughter, Nina Buchanan, recalls that her mother was very “bitter” about what had happened and the failing of Stockloser’s leadership.

For death in battle, Capt Sam Chapman’s words never fail to come to mind: he “is cut down in an instant with all his future now a page to remain forever blank. There is an end but no conclusion.” Jack Prugh had longed for the day when the war would end, when he would return to the woman he cherished and his two children, one of whom (Eric), he had never seen. Unlike the 19- and 20-year-olds killed in action, there were more pages, however, to the story of his life. More pages would be written and all of them with his image ever in mind.

“Mother painted a pretty good picture of him for us”

Son Eric Prugh has “no memories [of him]. He shipped out before I was born, never saw him…. Mother painted a pretty good picture of him for us [Eric and sister Nina].” He says he “got a much better picture” when, in 1956, he stayed for the summer with his grandparents in Brandon. We “went to a lot of his haunts and, basically, I slept in his bed. It meant a lot to me, the things revealed.” He learned about his participation in the church choir and of his “good tenor voice … Granddad Prugh spoke of him very much” and he “would always tear up when we were talking about him.”

“profound, it was profound”

The effect of Jack’s death on Helen was “profound, it was profound,” says Eric. She “made it clear” that the man she married in 1950 was “not my father and he could not measure up…. She told me on occasion when I was a teenager that marriage to my step-father was one of convenience so that we would have someone to provide for us.” Helene “often said how handsome he [Jack] was in his uniform and [she] was really proud that he had served. She held him on a pedestal.” The family stayed in Welland and Jack’s children grew up there. When Eric worked at the GM/John Deere plant, as his father and grandfather had, he learned more about his dad from Bert MacFarlane, who had worked with Jack. Bert “thought the world of him and coddled me at John Deere because of his connection.” He also learned that his dad could “party pretty hard.”

Jack Prugh was the standard by which life in his surviving family was measured for the next 75 years. Eric remembers his mom saying, when disciplining him, “If your father was here, he would not tolerate this.” He adds, “I give my mother credit for instilling it [my heritage] in me because she was my constant link to my past and my heritage.” Nina was “also influenced by my mom and the way we were raised to honour his commitment and sacrifice.”

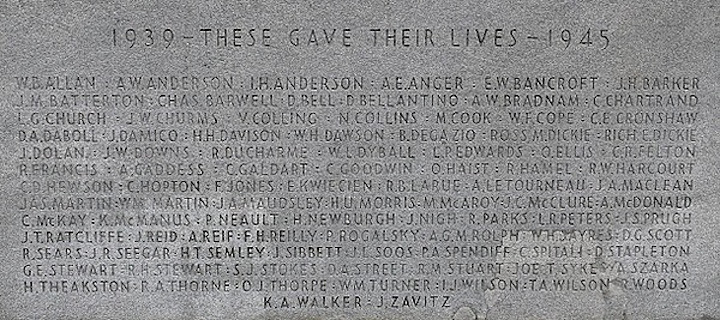

“running my fingers over his name”

Eric has never forgotten his father. Growing up in Welland, he lived close to the cenotaph that has his father’s name inscribed on it. He went there often, “running my fingers over his name.” Eric is now a lay chaplain who conducts his own Remembrance Day services, and his father is part of that special day. He also spent five years in Africa (2002-2007) as part of his own life of service. He understands his life as “part of [a] tribute to my father – no question!” He says, “I am humbled by my experience in life [and] in large measure I owe it to … his memory.”

“He apparently had a very high sense of justice”

“Mom used to tell me if Dad came home, [he planned to] go back to school and become a lawyer. He apparently had a very high sense of justice. I, too, have that. I never did that [become a lawyer] but I’ve lived a life of service to others.” As for Eric’s own children, they, like himself before them, have been “brought up to know” Jack Prugh.

According to Jack, Nina is “the family archivist” and has all the letters and pictures. To her mind, her father’s letter of 30 March 1944 is “kind of melancholy” with its references to the “little family they created.” Her mother had a “big chest in the attic full of letters and army stuff. Mom caught me reading them and took the chest and put it in the basement.” Over the years, most of the contents were lost, including a smaller group of letters kept in her dresser.

Nina’s memories of her father are many and varied, including his fondness for music, his acting in the operetta The Pirates of Penzance and singing in the choir; he had a considerable tenor voice. “Music was something for the Prugh family” and for her as well. He also had a penchant for art and particularly pen-and-ink drawings, which is her favourite medium (she is a graduate of the Ontario College of Art). Nina has an early recollection of sitting “in bed [with] her [mother] reading me a story and knitting scarves for the men overseas.”

“At that moment, I realized he was gone”

Unbeknownst to others, Nina harboured a child’s secret, the belief that her father was “just missing” and that someday “he would come back.” She nurtured that private belief until 1958, when a school trip (that included Eric) took her to Bergen op Zoom and her father’s grave. They had a bit of spending money and used all of it to buy flowers from a shop in a “little village store and put them on the graves,” including her dad’s. “At that moment,” she says, “I realized he was gone, and hoping he was still alive and [I would be] reunited with him” ceased. The letter informing her mother of her father’s death was in the collection of letters, but she never read it.

“he was the love of her life”

Helene remarried in 1950 because “she felt we needed a father and that was the reason she married.” But Jack Prugh, “he was the love of her life.” She “always set high goals” for us; she was “very strict [and believed] we should aim for the top. She felt she owed it to him.” Nina, who enjoys poetry and wrote it from an early age, came second in a poetry contest. She has kept some of the poems from that period of her life, including one never shared with others. She wrote it for her father and kept it private. “I believe this was written when I was in or around grade 7,” she says. As she read it over the phone, she cried softly.

Thoughts of a soldier’s child

It was so long ago for me

that a soldier died across the sea.

He died to keep

our country free

That war that broke

our family.

No Dad to take me

to the park.

To sit and watch

the fire logs spark.

To cuddle, read,

and keep me warm.

Or keep me safe

against a storm.

No Dad to walk

a kid to school.

That war was

very, very, cruel.

Some came home,

but some did not.

We gave up an awful lot.

“I am proud of his achievements and proud to keep his spirit alive”

Nina’s son, Dan Choate, visited his grandfather’s grave in July 2019. He says:

“I have always known about the life and fate of my grandfather, but it was rarely spoken of … I was always curious, however. With the internet, I’ve been able to find out more about him and his family. Something not available in my youth. I took the trip to learn more, first hand. To walk those steps, to see the sites and to imagine the horrors. I cried many times. It was very emotional. His service means the world to me. I am proud of his achievements and proud to keep his spirit alive through stories and photos. I work closely with the local Legion and it makes me feel good to do so. Our company even foots the bill for all veterans’ lunches each Nov 11th. It’s the least we can do.”

“You could say that he has been one of my finest teachers of life”

“I feel it takes a certain amount of age and maturity to understand and appreciate what happened,” Dan says. “As a child we of course learned about the wars and those who served, but how were we to truly understand? What great losses and hardships had we endured to compare? Honestly, I was in my 30s before it all ‘clicked’ for me and I became truly thankful … So, in short, his service makes me proud. It makes me appreciate all things. It makes me a better person. You could say that he has been one of my finest teachers of life.”

“Tears well up as the human condition touches the heart”

Lt Alan Earp took over the Argylls’ Pioneer Platoon in November 1944:

“Alas, I never met Jack Prugh, although I had heard well of him. Thanks to the material you have put together I know him better now. Virgil summed it up in six almost untranslatable words; ‘sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt’. (The best I can do is a prosaic: ‘Tears well up as the human condition touches the heart’.”)

Between 30 October and 4 November, 2 Argylls were killed in action and 11 wounded.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Remembered respectfully – An Argyll

Note: Capt Prugh’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Lt Jack Prugh

Jack Prugh and his mother

Graduation photo, Brandon College, class of 1936.

Eleanor Helene (Collins) Prugh

Jack Prugh with daughter Nina

Steenbergen, 1944

Service and sacrifice: cenotaph at Welland.

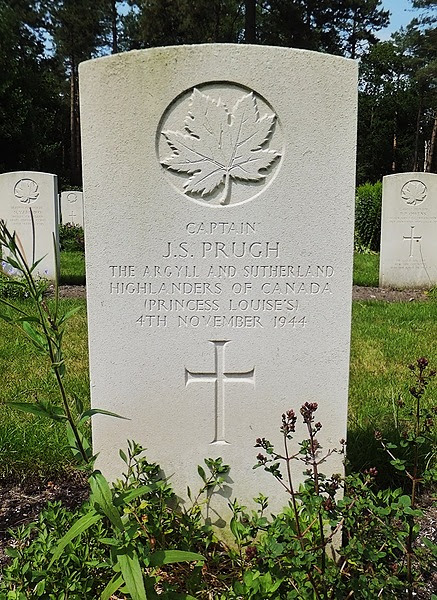

Dan Choate visited his grandfather’s grave (close-up below) in June 2019.