Foundation of the Regiment

Page 1 2

“To save lives and get a job done.”

Kilts and bagpipes are merely the distinctive symbols of a tradition rooted in Canadian military history for over 200 years – the Highland regiment. Since Confederation, the Highland Regiment has been most closely identified with the militia. In 1856, a Highland Rifle Company – forerunner of the present regiment – was formed in Hamilton.

Between 1880 and the First World War, as part of this heightened self-consciousness by Scots-Canadians and a rising interest in militarism generally, several kilted regiments were raised in cities across Canada. Hamilton had had a kilted military presence since 1856, when James Aitchison Skinner organized a Highland company; it later became a company of the 13th Royal Regiment, and eventually the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry.

The “idea” for a full Highland regiment in Hamilton “first took shape among the members of the St Andrew’s Society [of which James Chisholm was the long-time treasurer] and the Sons of Scotland [of which he was also a member].” Late in 1902, meetings were held and prominent members of the city’s Highland-Canadian community were asked to “take hold of the matter.” James Chisholm and his partner, William Logie (a captain in the 13th Regiment), took a leading, perhaps predominant, role in organizing locally and lobbying Ottawa. With the support of local Scottish organizations and clan societies, a deputation was sent to Ottawa to deliver a petition to the Minister of Militia and Defence. The minister, Frederick Borden, was less than enthusiastic about the potential cost and the Highland character of the proposed unit (he wanted the militia in a common uniform). Col. W.D. Otter, whom Logie canvassed for his opinion, was skeptical of the group’s ability to “get either the officers or the men and if we got both [of] these we could not get the money.”

Hamilton’s Scottish-Canadian elite moved quickly to fill the ranks of the officer corps and raise the necessary funds to outfit the Regiment in full Highland dress. As a result of broad community support and effective political organization, the Regiment was formed on 13 Sept. 1903 and gazetted three days later as the 9lst Regiment Canadian Highlanders. In winning the day, Chisholm and Logie used every reasonable tactic at hand. They were particularly adept at putting pressure on at the highest possible level, usually the minister, thus circumventing the normal channels of the Department of Militia and Defence.

The Regiment established its Canadian character by its choice of name – “Canadian Highlander” and affirmed its Scottish-Highland roots with its Gaelic motto – Albainn Gu Brath (Scotland Forever). Although there have always been individuals with ties to Scotland and Scottish/Highland forebears, the Regiment and its great symbols quickly came to represent the face of Canada, whether in 1903 or in 2014.

The First World War

Like the militia generally, the Regiment has suffered or prospered according to the dictates of government policy. Peace, fortunately, has been the norm during most of the Regiment’s history. Thus, the contours of the unit’s weekly and seasonal existence have been marked mainly by a routine of ceremony, drilling, lectures, training, exercises, administration, and recruitment, to say nothing of the rigours of mess life and an always full Regimental social calendar.

During the First World War, the Regiment acted as a recruiting depot, providing 145 officers and 5,207 men of other ranks for service in the numbered battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), especially the 16th and 19th, and the 173rd Highlanders. The latter was broken up for reinforcements, much to the chagrin of its men. Although the Argylls perpetuate both the 19th and the 173rd, it is the former that provides the Regiment’s most intimate connection with the Great War. The 91st gave the 19th all four of its commanding officers and its pipe major, Charles Dunbar, DCM (a pipe major of international renown), its command structure and about 30 per cent of its original establishment.

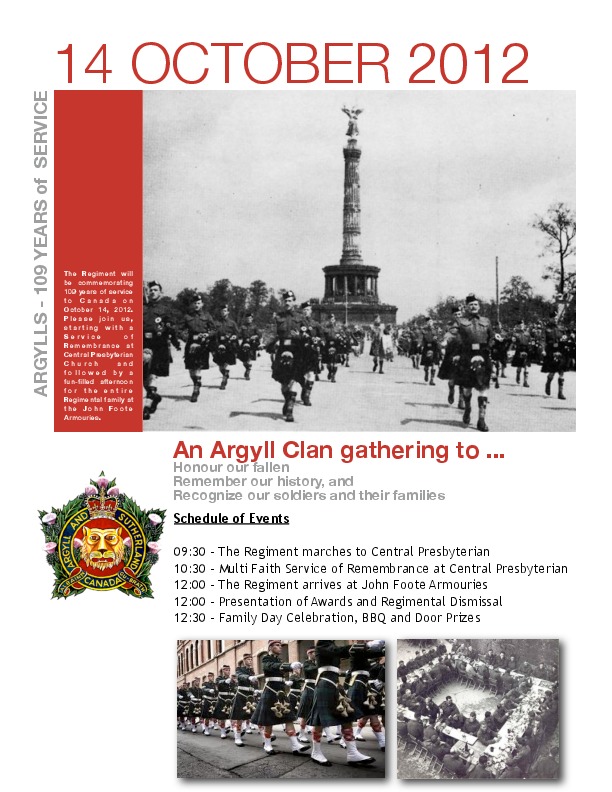

As part of the 4th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Division, the 19th went from the mud and misery of Salisbury Plain, England, to the mud and blood of Flanders. The Battalion saw its first action at St Eloi in April 1916 and went on to distinguish itself during battles at the Somme, Courcelette, Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, Passchendaele, and Drocourt-Quéant, and during the pursuit to Mons, to name but a few. In December 1918, its Pipe Band played a victorious Canadian Corps across the Rhine and into Germany: here was one of the memorable pictorial representations of Canada’s military past.

It has been said of the Argylls that “its history is written in blood.” During the First World War, the Regiment had provided 145 officers and 5,207 personnel of other ranks for service in the CEF, especially the 19th Battalion and the 173rd Highlanders (the Argylls perpetuate both units). All told, the 19th and the various machine-gun companies and 3rd Machine Gun Battalion lost 1,374 soldiers; over three times that number were wounded. The Regiment was less than two decades old and already the significant part of its history had been written in the blood of young Canadians.

The Inter-War Period

The Regiment went through the inter-war years, endured the general militia reorganizations, and prospered. Amalgamation with the 3rd Machine Gun Battalion, CMGC (less C Company of that unit), occurred on 15 Dec. 1936. Together they formed The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s) (Machine Gun). The (Machine Gun) suffix was dropped on 1 February 1941, from which date the Regiment has maintained its current designation. Not only was the inter-war unit large in numbers (rarely below 400, at times exceeding 600), it benefited from a considerable cadre of First World War veterans of all ranks. Tradition continued to play a pre-eminent role, and the Regiment enjoyed a visible civic profile through weekly parades on the streets, a close attachment to the city’s elite, and the activities of three highly active bands: pipe (still under Dunbar), brass, and bugle.

The Second World War

When the drums of war beat again in 1939, the Argylls were ready for mobilization – the structure, the men, and the numbers were all there – but for little else. Prior to mobilization in June 1940, there were occasional calls out. Argylls in kilts with Ross rifles and fixed bayonets, for instance, performed guard duty on the local canal and electrical facility. The problems of active duty were myriad: First War tunics and kilts for uniforms, Ross rifles for weapons, hollow pipes and bricks for the mortar platoon, and too many people with too little training.

The first months of the war were spent in and around Niagara-on-the-Lake, a dreary round of guard duty on the Welland Canal and local power facilities. There was little training and almost no new equipment; the first Bren guns, for example, would not arrive until December 1940. But there was time for setting the foundations for excellent administration and for addressing the usual range of problems associated with turning civilians into soldiers. It was during this period that the notorious “Mad Five” went AWOL, made their way to the Sunnyside amusement park in Toronto, and telegraphed the CO – “Having a great time. Wish you were here.” In May 194l, the lst Battalion entrained for Nanaimo, B.C., where it underwent several tedious months of route marches alternating with inspections.

September 1941 to May 1943 brought a sojourn in the sun – garrison duty in Jamaica. During this period, the reality of war was brought home by the fate of the Winnipeg Grenadiers (which unit the Argylls replaced in Jamaica) in Hong Kong, and of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (a sister unit from Hamilton) at Dieppe. It would have been easy for the Battalion to languish here, rum-sodden. Instead, under the command of LCol Ian Sinclair, the unit received new weapons and modern equipment, improved its administration, and began a complete program of small-unit tactics, fitness, and training of all sorts. In addition, the Battalion acquired cohesiveness at all levels, which would have been impossible to achieve under other conditions.

The men of the lst Battalion returned to Hamilton in May 1943 as soldiers. In preparation for overseas service, the Battalion lost its CO and all senior officers as well as all senior NCOs except its by now legendary RSM – Peter Caithness McGinlay. In August 1943, the unit passed inspection in England and joined the l0th Brigade, 4th Armoured Division. Advanced training, specialized courses, and schemes up to the divisional level became the order of the day, all of which were overseen by the new CO, J. David Stewart. The Argylls’ affection for him was instantaneous, broadened during training, and deepened with the experience of battle. His intuitive sense of battle (which could not be taught), his cool imperturbability, and his refusal to fight according to preconceived notions brought dramatic results.

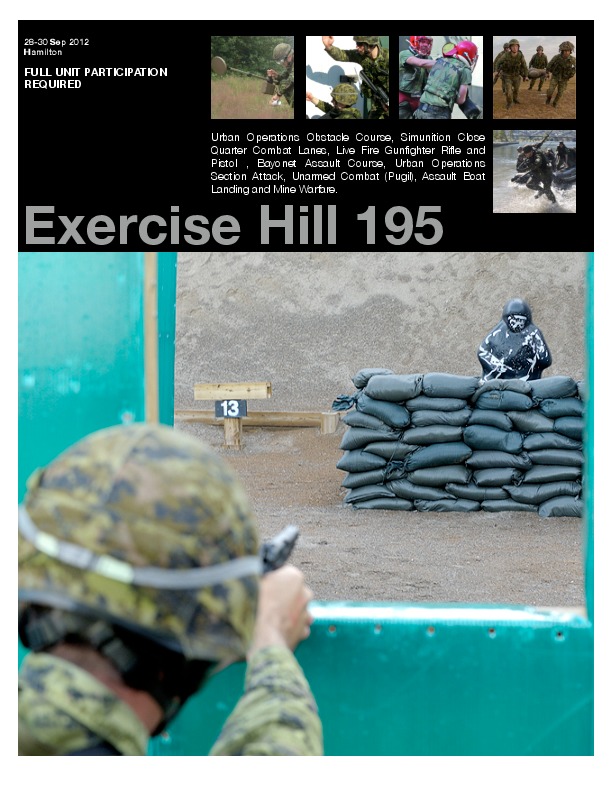

The unit’s first actions in early August 1944 were small successes fought along the road to Falaise. The first major action, Hill 195 on 10 August, was a brilliant and unorthodox success; Stewart led the Battalion single file through the darkness of night and German lines to capture the hitherto unassailable strong point. It was an act that historian John A. English has called “the single most impressive action of [Operation] TOTALIZE.” Less than 10 days later, in the Falaise Gap, a battle group consisting of B and C companies of the Argylls and a squadron of South Alberta Regiment tanks captured St Lambert-sur-Dives and held it for three days against desperate counter-attacks.

Night over daylight fighting; infiltration rather than frontal assault; innovation when orthodoxy failed; superb leadership; doggedness; great spirit; excellent administration; and close cooperation with the SARs (whom the Argylls revered above all others) – these were the benchmarks of Argyll success, and they were all evident in that first month of battle.

Of the experience of battle, Cpl H.E. Carter wrote to his mother on 13 August: “That life in the front is not fun, not glamorous – it’s dirty, and fierce and anyone that says they’re not scared is crazy. But I’m not going to talk much about that. We try and keep our spirits up, joke and enjoy yourself under fire and we do an exceptionally good job of it.” That very same day Capt Mac Smith put it best when he wrote to his wife: “The men are simply wonderful. They have done well, and are getting better. They grumble … and dig, and advance and dig, and advance. They stand shelling, mortaring and occasional bombing, and then stand up in their trenches and ask where the hell the food is.”

These first weeks gave the Argylls a “hard core of cynicism and self-satisfaction.” The depth of the former was best revealed when Stewart wrote of trying to protect his men “from our two enemies, the Germans and our own Higher Command.” He saw his trust as “to save lives and get a job done.” Like all infantry battalions, the Argylls suffered “inescapable losses” but the Battalion was “never shattered in battle.”

Through Moerbrugge, the Scheldt, Kapelsche Veer, and the Hochwald Gap to Friesoythe, the Kusten Canal, and Bad Zwischenahn, the Argylls were successful against the enemy – but there was more. Their losses (285 killed and 808 wounded) were the lowest in the l0th Brigade and their successes constant. Cynicism is a soldier’s rightful lot, and the Argylls never lost it. Self-satisfaction came with, and was sustained only by, success – despite the successive wholesale turnovers in the rifle companies. Neither quality was lost during 10 months of battle. It made them, as Capt Claude Bissell, would later remark, “a happy regiment and a formidable one in action.”

The lst Battalion provided the headquarters and one rifle company for the Canadian Berlin Battalion, a composite battalion that represented the Canadian Armed Forces in the British victory celebrations in Berlin in July 1945. Here again, the Argylls provided a memorable pictorial legacy of Canada’s participation in that war as our Pipes and Drums led the Canadian Berlin Battalion as Canada’s representatives in victory.

The Battalion returned to Hamilton in January 1946, where it was dismissed.