VE Day and the Argylls

It was May 1945 and the war in Europe was over. Across the Western world, jubilant citizens danced in the streets and bells, silent during the long years of war, pealed their long-awaited declaration of victory and war’s end.

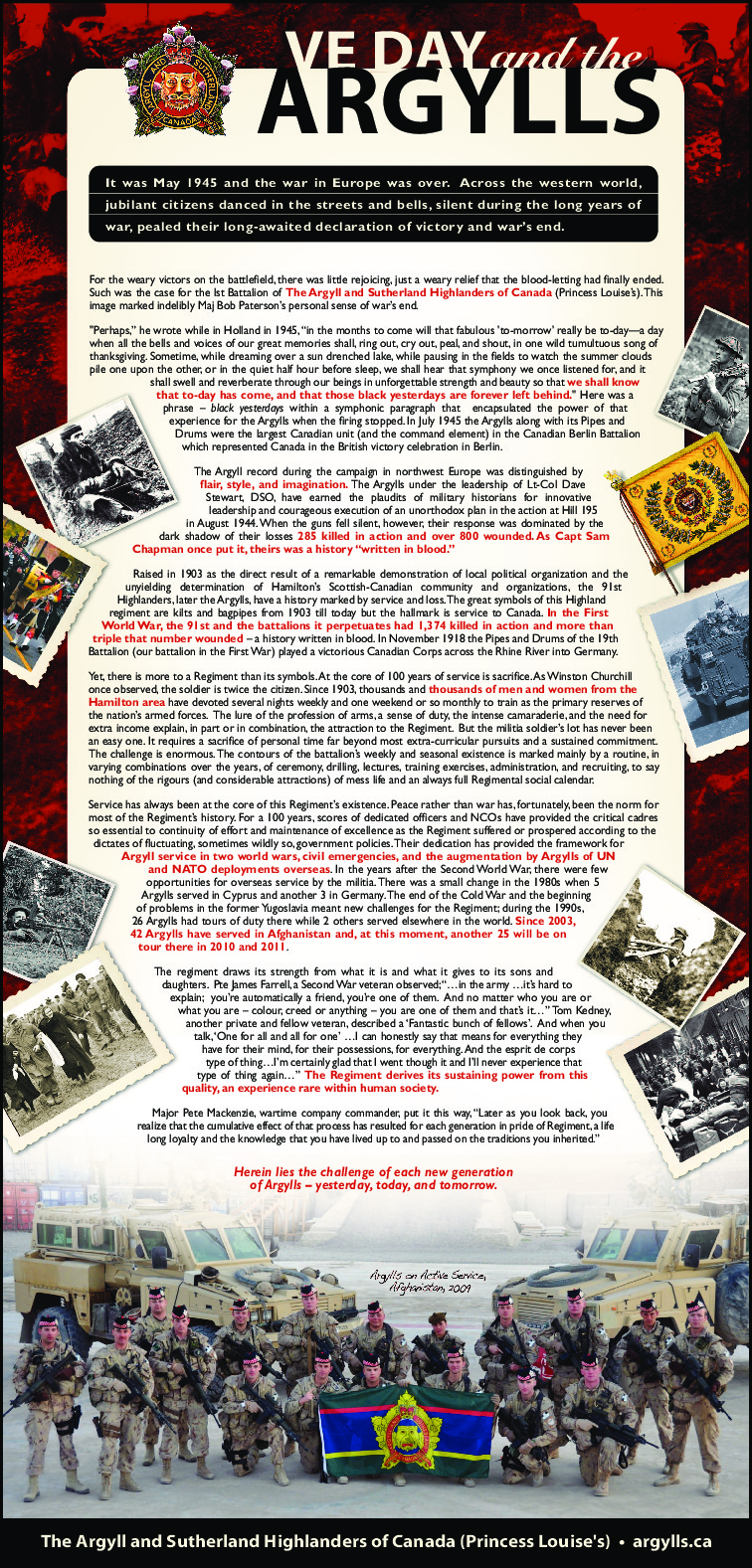

For the weary victors on the battlefield, there was little rejoicing, just a relief that the blood-letting had finally ended. Such was the case for the lst Battalion of The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s). This image marked indelibly Maj Bob Paterson’s personal sense of war’s end. As he had written in Holland in 1945:

Perhaps in the months to come will that fabulous “to-morrow” really be to-day – a day when all the bells and voices of our great memories shall ring out, cry out, peal, and shout, in one wild tumultuous song of thanksgiving. Sometime, while dreaming over a sun drenched lake, while pausing in the fields to watch the summer clouds pile one upon the other, or in the quiet half hour before sleep, we shall hear that symphony we once listened for, and it shall swell and reverberate through our beings in unforgettable strength and beauty so that we shall know that to-day has come, and that those black yesterdays are forever left behind.

Here was a phrase – “black yesterdays” – within a symphonic paragraph that encapsulated the power of that experience for the Argylls when the firing stopped. In July 1945, the Argylls, along with its Pipes and Drums, were the largest Canadian unit (and the command element) in the Canadian Berlin Battalion, which represented Canada in the British victory celebration in Berlin.

The Argyll record during the campaign in northwest Europe was distinguished by flair, style, and imagination. The Argylls under the leadership of Lt-Col Dave Stewart, DSO, have earned the plaudits of military historians for innovative leadership and courageous execution of an unorthodox plan in the action at Hill 195 in August 1944. When the guns fell silent, however, their response was dominated by the dark shadow of their losses: 285 killed in action and over 800 wounded. As Capt Sam Chapman once put it, theirs was a history “written in blood.”

Raised in 1903 as the direct result of a remarkable demonstration of local political organization and the unyielding determination of Hamilton’s Scottish-Canadian community and organizations, the 91st Highlanders, later the Argylls, have a history marked by service and loss. The great symbols of this Highland regiment since 1903 have been kilts and bagpipes, but the hallmark is service to Canada. During the First World War, the 91st and the battalions it perpetuates saw 1,374 killed in action and more than triple that number wounded – a history written in blood. In November 1918, the Pipes and Drums of the 19th Battalion (our battalion in the First War) played a victorious Canadian Corps across the Rhine River into Germany.

Yet, there is more to a Regiment than its symbols. At the core of 100 years of service is sacrifice. As Winston Churchill once observed, the soldier is twice the citizen. Since 1903, thousands and thousands of men and women from the Hamilton area have devoted several nights weekly and one weekend or so monthly to train as the army reserve of the nation’s armed forces. The lure of the profession of arms, a sense of duty, the intense camaraderie, and the need for extra income explain, in part or in combination, the attraction to the Regiment. But the militia soldier’s lot has never been an easy one. It requires a sacrifice of personal time far beyond most extra-curricular pursuits and a sustained commitment. The challenge is enormous. The contours of the battalion’s weekly and seasonal existence is marked mainly by a routine, in varying combinations over the years, of ceremony, drilling, lectures, training exercises, administration, and recruiting, to say nothing of the rigours (and considerable attractions) of mess life and an always full Regimental social calendar.

Service has always been at the core of this Regiment’s existence. Peace rather than war has, fortunately, been the norm for most of the Regiment’s history. For 100 years, scores of dedicated officers and NCOs have provided the critical cadres so essential to continuity of effort and maintenance of excellence as the Regiment suffered or prospered according to the dictates of fluctuating, sometimes wildly so, government policies. Their dedication has provided the framework for Argyll service in two world wars, civil emergencies, and the augmentation by Argylls of UN and NATO deployments overseas. In the years after the Second World War, there were few opportunities for overseas service by the militia. There was a small change in the 1980s when five Argylls served in Cyprus and another three in Germany. The end of the Cold War and the beginning of problems in the former Yugoslavia meant new challenges for the Regiment; during the 1990s, 26 Argylls had tours of duty there while two others served elsewhere in the world. Since 2003, more than 60 Argylls have served in Afghanistan.

The regiment draws its strength from what it is and what it gives to its sons and daughters. Pte James Farrell, a Second War veteran observed, “In the army … it’s hard to explain – you’re automatically a friend, you’re one of them. And no matter who you are or what you are – colour, creed or anything – you are one of them and that’s it.” Tom Kedney, another private and fellow veteran, described a “fantastic bunch of fellows.” And when you talk, ‘One for all and all for one’ … I can honestly say that means for everything they have for their mind, for their possessions, for everything. And the esprit de corps type of thing…. I’m certainly glad that I went though it and I’ll never experience that type of thing again.” The Regiment derives its sustaining power from this quality, an experience rare in society.

Major Pete Mackenzie, wartime company commander, put it this way: “Later as you look back, you realize that the cumulative effect of that process has resulted for each generation in pride of Regiment, a life-long loyalty and the knowledge that you have lived up to and passed on the traditions you inherited.” Herein lies the challenge of each new generation of Argylls – yesterday, today, and tomorrow.