William Alexander Logie, CB, VD (1866–1933)

William Alexander Logie was born in Hamilton, Upper Canada, on 26 April 1866, the son of the Hon. Alexander Logie, a judge of Wentworth County, and Mary Ritchie Crooks. The Logie (Loggie) family originated in the Moray area of northeast Scotland, not far from Inverness. His grandfather, William Logie (1781-1853), was the first to leave Scotland, one of many who were a part of the broad, structural transformation of the Scottish Highlands from the mid-18th century onward. One aspect of this changing social order involved the wholesale mobilization of Highlanders for military service on behalf of the British empire. In the last half of the 18th century alone, more than 50 battalions of Highlanders were raised for such purposes. William Logie received a commission with the Gordon Highlanders in 1800, serving in both the Egyptian and Peninsular campaigns. Emigration was another feature of the dramatic changes overtaking the Highlands, and British North America was a preferred destination of Highlanders.

After a stint as governor of Ceylon, Logie began a new life near Kingston, Upper Canada, and was a lieutenant-colonel in the Frontenac militia. His only son by his second wife, Alexander Logie (1823-1873), was born in Scotland and grew up within the Scots Presbyterian community of Kingston. After studying law in the office of John A. Macdonald, he moved in 1847 to the emerging commercial entrepot of Hamilton, by then the province’s second-largest urban centre. By the early 1860s it, too, had acquired a distinct, if not predominant, Scottish flavour (Scots made up almost 18 per cent of the town’s population). Alexander Logie was appointed a judge of Wentworth County and served in that capacity until his death in 1873; he was also a captain in the local militia.

William Alexander Logie was the first son and sixth child of a prosperous family, and young Logie enjoyed the usual advantages bestowed by the rising Canadian professional elite. Education was a much-cherished object of the Scots Presbyterian community, and Logie excelled in its pursuit. After a local education, he went to Queen’s University, renowned for its Scots Presbyterian character. A Prince of Wales prize-winner and a gold medallist in classics, he received his BA in 1887 (the same year he was admitted as a student-at-law) and the even rarer MA the following year. Called to the Ontario Bar in 1890 (with honours), he received his LLB two years later, again from Queens, and entered into partnership with James Chisholm, an up-and-coming Hamilton lawyer with a similar background.

As a young man, Logie took an interest in the militia, joining the Prince of Wales’ Own Rifles in Kingston in October 1883. Such attachments were by no means unusual among the late 19th-century Canadian elites and, in Logie’s case, it was a family tradition. After returning to Hamilton, he joined the 13th Battalion (later the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry) and rose through the ranks from private to sergeant. In 1890, he took out a commission and in 1896 received a Royal School of Infantry certificate. Nine years later, he commanded D Company.

Before the general militia reorganization of 1862, Hamilton had a Highland rifle company; when the various local companies were merged into the 13th in 1862, it became No.3 Company. The idea of a Highland unit, however, did not die. As one Hamilton newspaper later put it, “Scottish sentiment has always been prevalent, as has the desire to preserve Scottish traditions…. before 1900 individuals had their ideas and built air castles of when Hamilton would have the kilted boys.” In the heady years from the late 19th century until the First World War, militarism was in the air and Scottish-Canadians asserted their cultural identity with calls for Highland regiments. What historians have called “Highlandism” or “Tartanism” describes the way in which the great, and largely despised, symbols of the Highlands from the 1400s - warriors, kilts, bagpipes, and plaid - were appropriated in the 1800s as the symbols of Scotland. Canada witnessed a similar cultural phenomenon. From the 1880s, communities across the young Dominion had foisted Highland units upon reluctant governments.

Canada sent two volunteer contingents to the war in South Africa and, in 1900, “the idea for getting a kilted Highland regiment for Hamilton was again advanced.” The “general opinion was that a few enthusiastic Scotchmen had suddenly got bees in their bonnets.” The leaders of the local clan and Scottish societies secured some 400 to serve and obtained quotes from overseas for providing Highland kit. But, in spite of their best efforts, potential officers were hard to come by, especially a commanding one, and the drive sputtered to a halt.

Two years later, the plan was on the drawing board again. This time, the outcome would be different. For one thing, the organizers had become political; for another, they had approached Capt Logie, who was “soon a willing worker in the scheme.” Although the St Andrew’s Society and the Sons of Scotland “took hold of the matter,” Logie and his partner, James Chisholm, provided the critical leadership. The Liberal minister of Militia and Defence, Frederick Borden, was less than enthusiastic about the potential cost, to say nothing of the unit’s proposed Highland character (he preferred a common uniform for all Canadian forces). But Chisholm was a leading light of the Hamilton Liberal Association, an elite group that managed the party’s affairs locally; he became its president in 1903 and ran it with an iron, quasi-aristocratic grip. Logie canvassed the opinion of Col W.D. Otter on the matter, but Otter was skeptical of the group’s ability to get officers, men, or money.

Logie and Chisholm wasted no time in proving Otter wrong. They quickly exceeded the quota for recruitment, found the officers, and raised the funds to provide Highland dress. A draft letter written by either Logie or Chisholm in 1902 to local MPs noted that the proposed “officers are a fine lot of fellows and of good standing and large influence in the community.” The effort of 1902 had failed in this regard, whereas Logie and Chisholm succeeded. Moreover, Logie would be the proposed unit’s commanding officer. As for the troops, the “men are a particularly fine class of Scotchmen who own their own homes and have a stake in the community.”

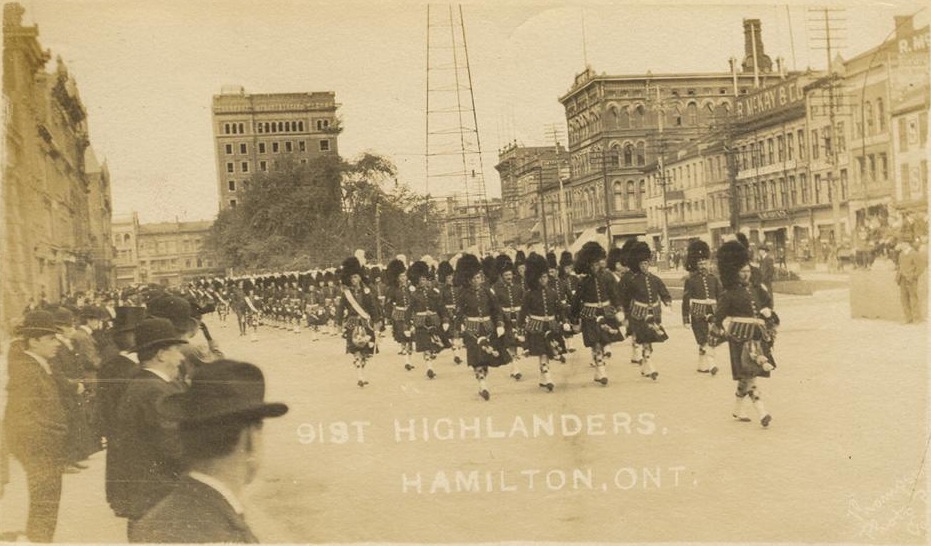

The two partners maintained steady pressure upon local politicians, both MPs and Senators, to forward their cause. Chisholm monitored all communications with Borden. When the minister curtly informed a local lawyer to forward his support for the Highland regiment “through the regular official channel,” Chisholm demanded that the minister explain himself. Borden denied the allegation, and by 17 August 1903 he informed Logie confidentially of authorization for the establishment of a Highland regiment. Logie, Chisholm, and Hamilton’s Scottish community were unrelenting and, in the end, they won the day. The Regiment was formed on 13 September 1903 and gazetted three days later as the 91st Regiment Canadian Highlanders, with its establishment fixed at four companies. The choice of name was deliberate. Despite the new Regiment’s obvious symbolic roots and beyond the Scottish-Canadian community’s deliberate efforts to foster a distinctive Scottish tradition within Canadian society, the name said it all - Canadian Highlanders. And that name provided, one supposes, an equally deliberate juxtaposition with the new Regiment’s unique Gaelic motto (chosen later): Albainn Gu Brath (Scotland Forever). The number - 91st - provided an association with the British Army’s 91st Argyllshire Highlanders.

A newspaper report of 12 September 1903 noted that the “new corps has a most efficient staff of officers … and there is no reason why the 91st Regiment should not occupy a place among the pick of the Canadian militia in a very short time.” Part of the objection to the new force had stemmed from the premise that such units “were being maintained for show and ceremonial purpose alone, and of no value as a fighting force.” The writer offered the hope that the 91st would be a “well-drilled” unit “easily made into a fighting machine worthy and ready to answer the bugle call,” following in the footsteps of their Scotch forebears.

Logie had a reputation as a “very modest” man deemed “certain to make an excellent commanding officer.” He now set about his tasks with enthusiasm and a sure grasp of the exigencies of regimental life. If anyone thought that the newly formed regiment would be merely a showcase for parade-square soldiers and ceremonial drill, they were quickly disabused. On 25 September, he held the first parade and addressed the troops, making it clear that “there would be no room … for men who could not or would not attend every parade.” He promised them hard work, good drill, and a portion of their pay to a fund “to purchase kilts.” By November, the key appointments were in place, service uniforms had been issued, temporary quarters were almost ready, some officers had already been sent on course, parade nights had been set (Thursdays), troops practised company and section attacks, and arms were issued.

With its administration, routine, and kit in order, the Regiment paraded six companies in April 1904, and the Pipe Band had been reorganized following some initial, albeit unspecified, disgruntlement. The following month the Regiment held its first dress parade, the Officers’ Mess was organized in temporary quarters on Hughson Street North, and the unit passed a critical inspection by the hitherto skeptical commanding officer of No.2 Military District (over 300 were out for it). In June 1904, the Regiment held its first church parade at St Paul’s Presbyterian Church and later that year received its Colours. Prizes and trophies were regularly awarded for various forms of competition, and the unit worked towards its annual fall exercise and inspection. In 1907, the Militia Council noted “the steady progress of the Regiment” and expressed its congratulations.

Logie’s voice is rarely heard through his command, although newspaper accounts occasionally give snippets of addresses to the troops. Nonetheless, his command presence was felt everywhere. He set a regimental style at the outset that wove together the ceremonial aspects of soldiering - a critical facet of a militia unit - with a weekly emphasis upon drill, training, shooting, commitment, and continuity of effort. The maintenance of Highland dress weighed heavily from the outset, and he drew upon the local community for support. Moreover, he put the unit’s finances in the hands of Chisholm, setting a standard for proper accounting and annual financial statements. He oversaw the immediate reorganization of the Pipe Band so that it could, along with the Brass Band under Capt Harry Stares, provide a Regimental presence at public events across the province and in the United States. The Officers’ Mess was organized on a committee basis; the financial committee was composed of himself, Chisholm, and the honorary lieutenant-colonel, J.R. Moodie. The development of the mess itself was entrusted to Capt Walter Wilson Stewart, who happened to be the local architect in charge of the building of the new armouries (completed in 1908 and opened in 1909). The 91st grew from four to eight companies under Logie’s command, a fact attributable to his own success and the Logie/Chisholm political connections. Good training, professionalism, commitment, and style were the hallmarks of Logie’s command. When he left in 1909, he had fulfilled the hopes of 1903, and little more could be asked of him than that.

Logie’s military career continued after he relinquished command. He took command the 15th Infantry Brigade and was promoted colonel in 1910, the same year that he became a trustee of Queen’s University. From the 15th, he went to the 4th Brigade. He organized the 13th Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery, Howitzer, in September 1913. At the outbreak of the First World War, there were new requirements for his talents, and on 1 January 1915 he took over as the OC for No.2 Military District. He was promoted brigadier-general in September of that year and major-general in May of the following year. Upon the latter promotion, he became GOC of No.2 Military District.

Logie handled this command with his customary dedication, sang-froid, and unflappable manner, with an ever-keen eye for detail, improved organization, and new initiatives. As volunteer enlistments dropped late in 1916, he provided the impetus for new drives, “united effort,” and the assistance of women. He encouraged the plans to recruit native Canadians throughout his district and to allow them a full two companies in the 114th Battalion. Black Canadians were also eager to volunteer, but Logie was skeptical about their reception in the battalions. He tried to find units willing to accept them, but his efforts proved futile and he concluded that the situation was “hopeless.” When, in 1917, five natives objected to serving in the black No.2 Construction Battalion, Logie intervened to resolve the dispute. Later that year, he ordered troops to quell a disturbance caused by veterans and urging the police “to do their part.” Not surprisingly, Logie supported the Canadian government’s reluctant movement to conscription. For his “valuable services in connection with the war,” he became a Companion of the Order of the Bath on 3 June 1918.

At the war’s end, Logie returned to his legal career as a judge of the Supreme Court of Ontario, High Court of Justice, serving in this capacity until his death on 6 June 1933. Few Argylls have enjoyed such a distinguished career. Logie excelled academically, militarily, and judicially. He had also been a superb athlete, captaining a championship football team in 1890. No Argyll has risen as high in rank. Although the war and his career took him to Toronto, the 91st remained his second home. Rarely given to outward manifestations of pride, he was clearly chuffed by his only son’s (Alexander Chisholm Logie) decision to join the 91st. The general rarely missed a Regimental event, and on all special occasions he was front and centre, taking a rightfully earned pride of place before all others. Sober yet never solemn, proper yet never pompous, equally adept performing ceremonial drill or in the field, he was a compassionate man whose gentle and kind countenance looks out still from the walls of the Officers’ Mess of his Regiment. And in the northeast corner of the bar-room beside his large pewter mug is a delightful caricature of Logie, in ceremonial dress, wildly riding a child’s hobby-horse, a wonderful example of the “cheerful humanity” that Maj Hugh Maclean characterized as uniquely Argyll.

Logie left his wife, two daughters, and his son. The legacy of service passed to Alexander Chisholm Logie, who, as OC of B Company of the Argylls, was killed in action on 20 October 1944. It is fitting that Lt.-Col. Logie’s portrait has been donated to the Officer’s Mess in memory of his beloved son.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian