Pte William George Wingate (1909–44) (B 45978)

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

I took note of Bill Wingate in November 2020 after rereading Piper Murdo Miller’s comment about him. Miller was the stretcher-bearer who thought Wingate was wounded and got him back to the Regimental Aid Post. I knew nothing about Wingate beyond that. I decided to do an Argyll Poppy for him, and his life proved intriguing. He was one of the many poor children shipped to Canada. He joined the army to return to England and see his family again. Bill Wingate told an army examiner that he was “unconcerned” about the outcome of a war in which the young fatalist would become an early Argyll casualty.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte William George Wingate (1909–44) (B 45978)

DW 5 August 1944

“Left school at the age of 14 to come to Canada”

William (he was called Bill) George Wingate was born in London, England, on 1 August 1909, to George Frederick Wingate (1883–1944) and Edith Amy Farmer (1885–1971), the second of their three children; he had an older sister and a younger brother. His parents married in 1905, and, by the time of William’s birth they lived in Islington, London, in Harringay. There, he “completed ‘6’h Grade” according to his army records.” He “left school at the age of 14 to come to Canada.”

“Fagan’s [Fegan] Homes”

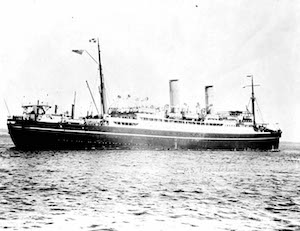

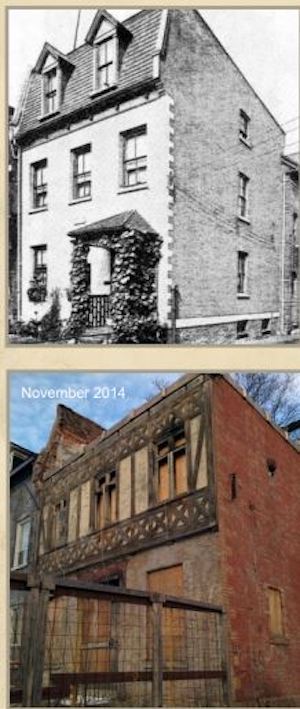

From 1869 until the late 1930s, over 100,000 children were sent to Canada from the United Kingdom. Child emigration resulted from poor social and economic circumstances. Churches and philanthropic institutions sent children who were orphaned, abandoned, or poor to Canada to work on farms and, perhaps, secure a better life. Often their hosts regarded them as cheap labour for farms or domestic service. Bill Wingate and his brother George F. Wingate (1911–72) left Liverpool on 24 April 1925 on the SS Montclare, arriving in Quebec on 2 May. They travelled third class; their passage had been paid by “Fagan’s Homes” [sic] on Church Street in Toronto. As landed immigrants, they intended to reside in Canada and to work on farms. James William Condell Fegan (1852–1925) started working with “street boys” in London in 1870. Thereafter, he set up homes and orphanages in England and began sending older boys to Canada in 1884. He had a home in Brandon, Manitoba, and Fegan Distributing Home in Toronto. Between 1884 and 1915 on one hand and 1919 to 1939 on the other, Fegan settled some 3,200 boys in Canada. A note in the records reads: “From J. Fegan, Training Farm, Groudhurst, Kent.” Bill Wingate and his younger brother were among the boys sent to Canada.

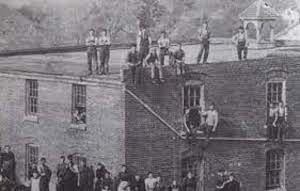

Naturalized in 1925, Bill worked for five years “on farm” and then ten years at the “Huttonville Knitting Mill to date of enlistment.” His 1944 interview provides more detailed information: he was a general labourer on a mixed farm in Huttonville, Uxbridge, from 1925 to 1931. H. May and S. Ward owned it and paid him $10 weekly. The hamlet was in a prosperous agricultural township and situated near Mississauga Road and the Credit River. The village took its name from James P. Hutton, the mid-19th-century mill owner who utilized the local water power. By the 1890s, the village also boasted John McMurchy’s woollen mill. The mill and the hydro dam ensured Huttonville’s prosperity through to the mid 20th century. From 1932 to 1940, Bill Wingate worked at the mill “operating Textile machines” such as carders, pickers, and winders. He made $12 weekly.

“Enlisted to get to England and see his family”

The Argylls received mobilization orders on 21 June 1940. Recruiting began in earnest five days later. Bill Wingate enlisted on 11 July 1940. At the time he resided in Brantford, and according to his occupational history form, McMurchy’s had promised him re-employment upon discharge (he had no other ambition or employment preference for the post-war period). Both parents were alive; George was a “labourer” in King’s Cross, London, while Edith lived in Kimberley Gardens, Harringay. When asked for their reasons for enlistment, most recruits expressed their motivation in terms of adventure, duty, patriotic reasons, and family or friends already in service. Bill Wingate’s incentive stands apart from all others. In January 1944, he told an army examiner that he “Wanted a chance to come back to England.” There was more to it than a return to the “sceptred isle” and “demi-paradise” of John of Gaunt’s speech in Richard II. Wingate expanded on his impulse in another interview four years later; he desired to “see his family.” Overseas service offered him the best opportunity. His younger brother would also join the army.

Bill Wingate was 5’, 7¾”, 160 lbs., with a fair complexion, blue eyes, and fair hair; he belonged to the Church of England. He married Evelyne Troyer (née Brasher; 1903–61) on 28 September 1940 in Huttonville; his wife was English-born and previously married; she had three daughters. There was little time for sports or hobbies in Wingate’s life. His personnel file is rather exceptional in that regard. It lists one team sport – hockey, in which he played goal – and that is it.

“the working-class families, the Depression families”

The new recruits were, as one of them expressed it, “from – if you like – the working-class families, the Depression families.” Lt Bill Whiteside of B Company recalled “we had chaps with us that didn’t really know which end of the gun went ‘Bang!’ it was fascinating. People who just didn’t know anything – people who had never been away from home before. They were lonely, they were scared…” There was an air of unreality to it all: between 784 and 823 other ranks in the early months with just “700 Ross Rifles, but no machine guns.” They performed guard duty on canals, a movement in September 1940 to Niagara Camp and plenty of disorganization. Pte Jim Potticary was dismissive: “We had kilts and things like that, but you can’t fight a modern war in a kilt…” The emphasis was on organization, administration, and discipline. The adjustment to army life and training was ongoing at all levels. In 1941 Pte Wingate found his permanent home within the battalion, #12 Platoon of B Company. Maj Bill McClemont and CSM George Campbell of B “ran a good company,” Whiteside thought. “Really a good company.” The life of a Highland battalion accorded high prominence to the Pipes and Drums (see Piper Richard McDonald), whether morning reveille, guard duty, company and battalion parades in Hamilton, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Camp Nanaimo, B.C. (May to August 1941), or the routines of life in Jamaica (September 1941 to May 1943).

“… the weather was warm, the people were black”

Jamaica was a shock. Pte Tom Sayer, B Company, put it succinctly: “… the weather was warm, the people were black.” There was more. Pte Mac MacKenzie of D Company captured the collective feeling simply: “Poverty, never seen it like that in my life.” Pte O.C. Taylor of B Company exclaimed that “it was a bit of a shock to see the way they lived. I thought we were bad off here, but boy, they were in bad shape. Owned nothing …” Pte John L. Kelly, B Company, remembered the intramural company sports, “basic training,” “route marches,” and “little manoeuvres.” He liked the NAAFI (Navy, Army, Air Force Institute) for tea and the billiard tables. The companies rotated through guard duties so that the battalion could provide advanced training at a facility at Newcastle.

“advanced training”

There were new weapons, new equipment, and in January 1942 B Company distinguished itself with qualifications on the new Bren guns (75 of 133 qualified in the first practices). B then relieved D Company at Newcastle on 12 February 1942; in August, there was another two weeks of “advanced training” for B. On 11 December B Company “carried out a company scheme to-day at Stoney Hill… The Anti-aircraft platoon and a Mortar section were in support of the company.” There was also a new training facility “to be used shortly” at Moneague, which at a “little more than 1,000 feet above sea level” was about one-third the height of Newcastle. The air was cool and “there are large tracts of land, in the surrounding area, adaptable to field schemes and training.” The training there was “pretty hard” and tactical so that company and platoon commanders learned to handle their units. In January 1943 the rifle companies commenced training on “a new assault course” with “high mounds,” “deep ditches,” and a fence. By early May the Argylls were preparing to return to Canada and the unit sailed on 20 May 1943. Pte Taylor, B Company, was “glad to leave … It got that way, monotonous … day in, day out, week in, week out, and so on. I was ready to go.” After docking at New Orleans on the 23rd, they boarded two waiting CPR trains arriving back at Niagara Camp at 2200 hours on the 25th.

“Rifleman, likes the work and seems well placed”

Pte Bill Wingate adjusted well to the army and officers considered him reliable. With almost three years in the Argylls, he had no disciplinary issues. That ended back in Canada. He lost seven days’ pay on 1 June 1943 for being AWOL for two days in late May; he was impatient for leave and went to Huttonville and his family. When interviewing Wingate at camp on 30 May 1943, the army interviewer noted his “Clean Crime sheet,” which was on the verge of being erased two days later. The officer found Wingate:

Of quiet manners, but co-operative and responsive, this married soldier has average Army ability. Well-built, he weights [sic] 170 lbs. is 5’ 10” tall is ‘A’ Category [health rating] and has no physical complaints … Football, softball and volleyball are his sports, while he attends shows and reads ‘a little’ for amusement. At present is Rifleman, likes the work and seems well placed.

The recommendation was hardly surprising: “Infantry, Non-Tradesman (Rifleman). – Suitable for Overseas.”

“#1 Bren Gun”

Wingate received “Debarkation” leave from the 1 to 10 June. He may have overextended his leave because he lost another eight days’ pay on 9 July for being AWOL again; it seems likely the time was spent with his wife and step-children. On 13 July he made out his will, giving “all my estate to my wife.” On 24 July, he became “#1 Bren Gun” in 12 Platoon [#1 on the Bren light machine gun fired it; #2 reloaded and changed heated barrels].

“See his family”

In the weeks at Niagara, the Argylls lost 7 officers and 120 men because of age or medical condition and gained 152 reinforcements directly from Camp Shilo, Manitoba. Lt-Col Ian Sinclair left the battalion (he was a First War veteran) and Maj Art Hay took over as acting CO. Maj Don “Pappy” Coons replaced McClemont as the officer commanding B Company. The unit entrained for Sussex, New Brunswick, on 10 July, arriving on the 11th. On 23 July the Queen Elizabeth with the 1st Battalion Argylls on board left its Canadian harbour and arrived in Scotland five days later. From there a train took them to Camberley in England, where they had their first parade on the 30th. In early August, passes were issued to “50% of the unit personnel.” Bill Wingate was in England again and his family nearby. He received seven days’ personal leave plus 48 hours in early August. Later, his obituary noted that he “arrived in the old country just shortly before the death of his father.” “It was the first time he had seen his father since leaving England.” In early September, the battalion moved to quarters at New Hunstanton. He was “AWL FROM PARADE on 7 Sept 1943 and confined to barracks for seven days.

“Is little concerned with the war or it’s [sic] outcome”

Like the rest of the battalion, Wingate was interviewed in the early months of 1944. The army examiner found him “fair” in deportment, “friendly shy” in disposition, “clean” in grooming, and “sturdy, heavy set” in physical appearance:

Not very bright but steady and reliable. A willing worker. Not imaginative. Likes the army and is well adjusted. Enlisted to get to England and see his family. Is little concerned with the war or it’s [sic] outcome.

As for suggested possibilities for military employment, there was but one: “Inf. rifleman.” He was AWOL for 10 hours on 7 February 1944, losing seven days’ pay. Wingate’s absence may be explained by his father’s condition; he died in May 1944. He was AWOL again from 2359 hours on 17 June to 0630 hours the following day; he was confined to barracks for seven days. Wingate’s records are incomplete. His family was close and he may have been late returning from a brief leave or pass and a visit to his mother.

“glad to hear you are keeping so well”

Pte Wingate embarked for France on 19 July 1944 and disembarked the next day. A letter from a friend or neighbour in Huttonvile four days later provides a glimpse of Bill Wingate and his family. Mrs F. Barnett replied to “your nice welcome letter … + was glad to hear you are keeping so well.” On the home front, she wrote, “we sure are busy these days we are right into the raspberry crop now + what a dandy crop we have.” She reported on the heat (“90 to day”) and “some bad storms this summer + has done lots of damage.” “Well Bill, she concluded, “I bet you are anxious to get the job over with more so now when you know how good every thing is going + for the bust up in Germany…”

“a damnable life of war”

A letter from his brother George on 31 July [1944] acknowledges “your letter received today” and “guessed from what mum said in her letter that you must be in France.” He had “forgot to get you a card for your birthday which is tomorrow, but I wish you many happy returns of the day anyway and I’ll be thinking about you too.” George was in a reinforcement unit, which went to the ranges at Aldershot “yesterday.” “Looked for your name in the Butts [the backstop on a rifle range],” he wrote, “but didnt [sic] find it [possibly a reference to Fegan boys putting their names on the bricks of the distributing home in Toronto].”

I hope you get lots of Jerries, and get one or two for me just in case I dont [sic] get a chance at the buggers myself. Give them hell for taking us away from the life we love to a damnable life of war. I hope you get one for every day you have had to spend away from Eve and the kids. Remember all the good times we had before this war took us away from home! Well we are going to have lots better times than that when its [sic] over … Best of Luck Bill and take care of yourself, I hope to see you there soon.

The Argylls’ introduction to the battlefield was not immediate. Sgt George McGowan was wounded on 25 July. Pte Percy Samuel Hindle and another Argyll were killed by artillery fire on the 29th. Their deaths drove home the reality of war. The terrible destruction of Caen cast its own awful pall. In the early days of August, flies, heat, and dust exacerbated the effect on the battalion from heavy shelling from mortars and artillery and seemingly ubiquitous snipers. Pte James Bannatyne and three other Argylls died on 2 August at Bourguébus, while 14 were wounded. The Regimental Aid Post (RAP), burial parties, and regimental laments for the dead became part of the fabric of Argyll life.

“rapidly acquiring battle-sense”

In Maj Hugh Maclean’s words, in those days, “morale stayed high” and the battalion “was rapidly acquiring battle-sense.” On 5 August, “the Regiment got its first chance to engage in active movement against the enemy, instead of merely sitting and ‘taking it.’” The unit war diarist recorded that:

…At 1530 hours word was received from Brigade H.Q. that Tilly [Tilly-La-Campagne] had been evacuated … and we were ordered to send a platoon forward to occupy it. The authenticity of this report was questioned, inasmuch as somebody still in the area … was continuing to engage our area with Small Arms and Mortar fire. Nevertheless, a Platoon of B-Coy, under the command of Sgt. McLaren, was ordered to occupy Tilly.

The platoon left at 1630 hours and by 1700 hours was seen to enter the village … At the same time they were engaged on three sides by very intensive Small Arms and Mortar fire. It was appreciated by the C.O. that Tilly was still occupied in force and that this platoon would have to withdraw. He therefore ordered a heavy concentration of three Artillery Regiments on known enemy locations. With this help and the assistance of very heavy mortar fire, the platoon commander succeeded in bringing back 23 of the original 30 men. In this action, Pte. Ed Purchase sacrificed himself fearlessly in order to cover the withdrawal of the remainder of his section. When last seen he was advancing towards the enemy firing a Bren gun from the hip, thereby facing certain death [in the event, he was captured unharmed].

“Bill Wingate was badly cut up. I patched him up and got him down to first aid…”

For ACpl Burt Eden, B Company, the experience provided a vivid memory because “We were pinned down a long time, that time. That’s where I prayed a little bit.” The sections of 12 Platoon took up positions in different parts of the town. Lt Joseph Girard, the platoon commander, was wounded and brought out by Eden. Bill Wingate was presumed wounded when a mortar round hit the slate roof of a building. Pte Murdo Miller, a piper, was a stretcher bearer attached to B Coy. “I went in, he recalled:

I went in with the first platoon, went in to attack the German situation there, and yeah, it was rough. Eleven of us came back in the platoon. Well, when the platoon was full strength it’d be what, about thirty-four people.

…I treated some on the way back in, you know, but it was certainly a hurried up patch job, I’m telling you. But back in, and then we had the worst casualties, when they threw a mortar over and the hit the slate roof right above us. One was killed, well he died. I forget now how many were injured. [Pte] Bill Wingate was badly cut up. I patched him up and got him down to first aid as quick as I could. And I guess I didn’t see the one wound up in the chest, had gone up through or something. But it didn’t matter anyway ’cause he, I think we done the right thing by getting him down to the doctor as soon as possible.

Wounded on the 5th, he died of wounds on the next day and was buried that day in the “Mondeville Cem for Cdn Soldiers.” In the forms for Pte Wingate’s estate, Evelyne Wingate wrote “cannot give age of mother Father Sister or brother or place of marriage of mother + Father. All been [being] in England I cannot obtain the information [.]” According to his obituary, his mother, two brothers (George and Harry) and one sister (Kathleen Farmers), “all are residing in the old country.” Left in Canada were his wife “formerly Evelyn [some sources drop the “e”, some do not] Troyer, and three step-daughters, Bernice, Dorothy and Evelyn, all of Huttonville. There were few personal effects: the usual red identity disc, his regimental Glengarry and badge, a pair of Argyll shoulder flashes, a wallet, a writing case and photo, a key, and a chauffeur’s licence.

Evelyn Wingate’s obituary notes that she was “predeceased by son William Troyer, daughter Florence Mary and husbands William Amos Troyer, William Wingate.”

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Note: Pte Wingate’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy for the Field of Remembrance.

Wingate’s family attended All Saints Church, Battlebridge, Islington, UK, and he was baptized there.

Wingate’s family attended All Saints Church, Battlebridge, Islington, UK, and he was baptized there.

SS Montclare, 1921.

SS Montclare, 1921.

Fegan Distributing Home in Toronto settled some 3,200 boys in Canada.

Fegan Distributing Home in Toronto settled some 3,200 boys in Canada.

McMurchy & Co. Woollen Mill, Huttonville, Ontario.

McMurchy & Co. Woollen Mill, Huttonville, Ontario.

Workers at McMurchy & Co. Woollen Mill, Huttonville.

Workers at McMurchy & Co. Woollen Mill, Huttonville.

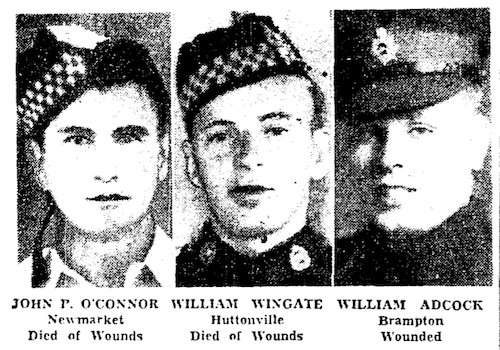

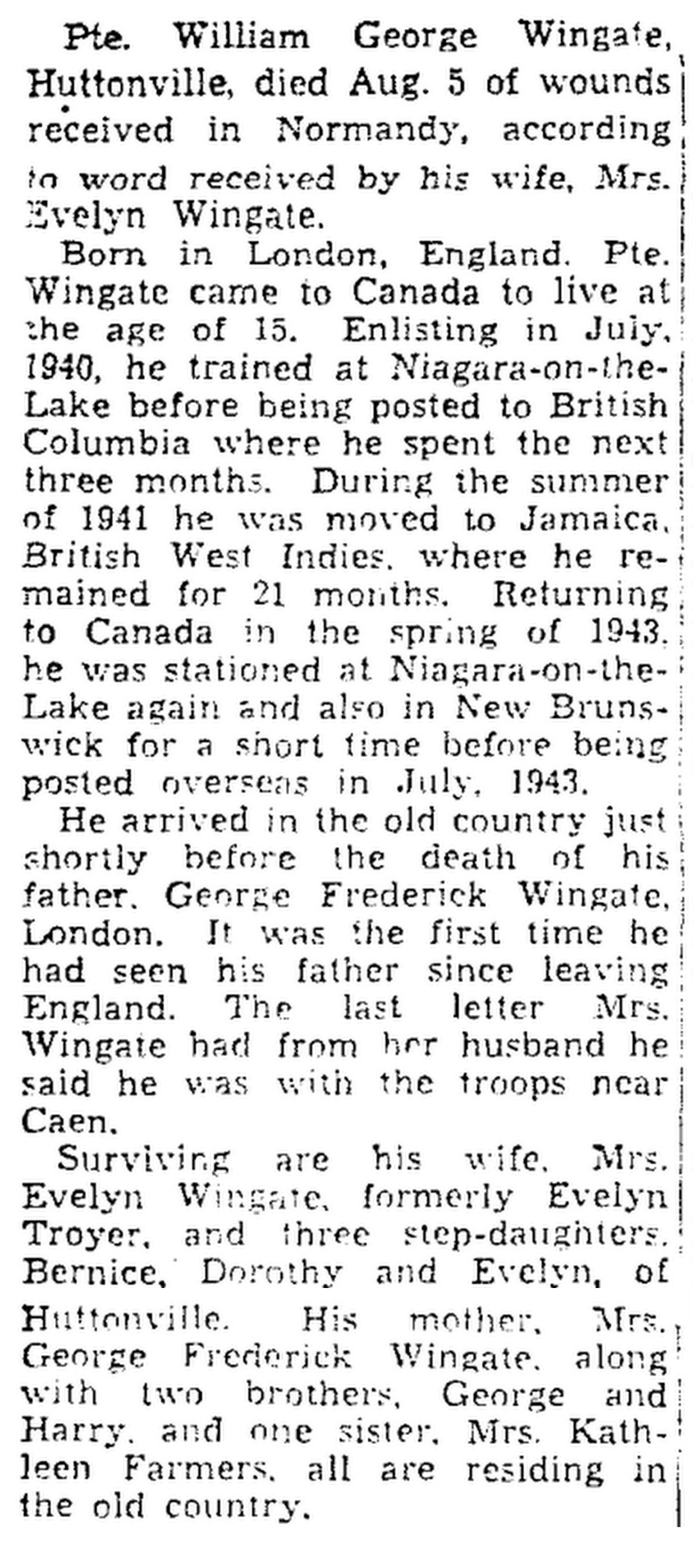

Newspaper clipping: deaths of Wingate (centre) and John P. O’Connor; William Adcock, wounded.

Newspaper clipping: deaths of Wingate (centre) and John P. O’Connor; William Adcock, wounded.

Gravestone of William’s brother, George F. Wingate (1911–72).

Gravestone of William’s brother, George F. Wingate (1911–72).