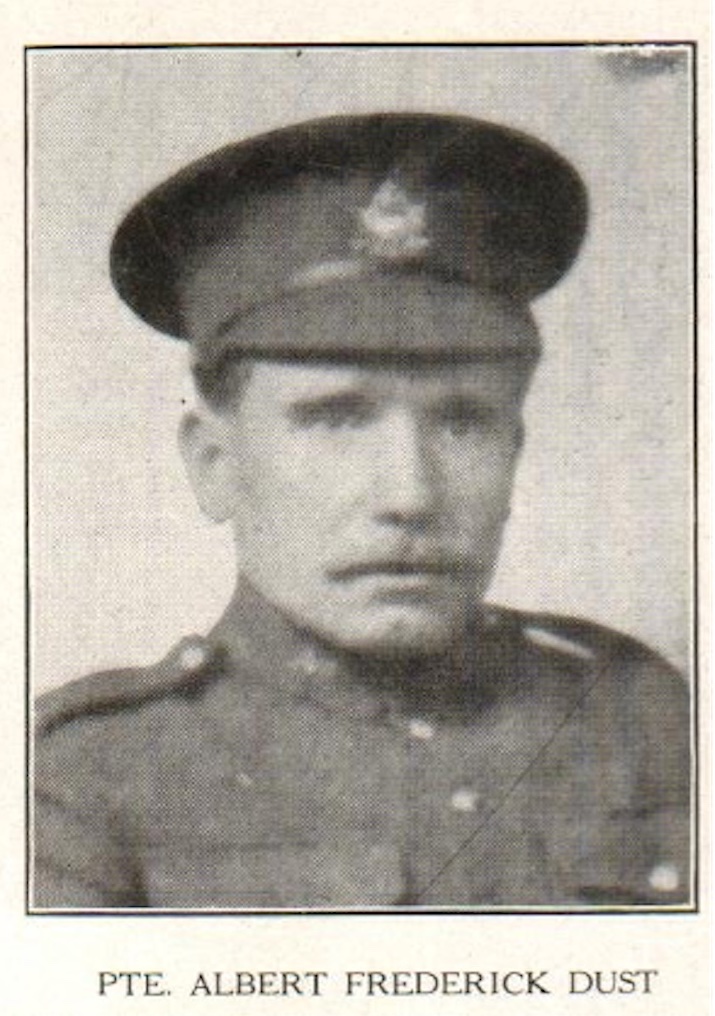

Pte Albert Frederick Dust, 123035, 1881–1916

By LCol (ret) Tom Compton, CD, BA

Director, Argyll Regimental Museum & Archives

Pte Albert Frederick Dust was born on 10 Dec. 1882 in Mile End, Middlesex, England, the son of Richard Dust (1844–1893) and Emily Bark (1850–1926); his twin sister was Emily. His sister Isabella Martha Dust was born on 4 Oct. 1885 (1885–1976); he was baptized on 26 Nov. 1890 (age 7) at St Peter, Mile End Old Town, England. A brother, Arthur James Dust, was born on 16 March 1894 (1894–1959).

In 2 April 1911, he was single and living with his mother in Mile End Old Town. He married Ada Caroline Palmer (1893–1938) that month. Their son Albert was born in April 1912 and died the same month. The Dusts left for Canada on 1 May 1913 and were living in London when Herbert was born in September 1913. Herbert R.J. Dust (1913–15) died in London, Ontario, of scarlet fever. On 30 Aug. 1915, they were living at 86 Oak Street.

Pte Dust enlisted with the 70th Overseas Battalion on 30 Aug. 1915. He was 5’, 4 3/4”, with a dark complexion, grey eyes, and mid-brown hair; he was a “labourer” and belonged to the Church of England. His wife, Ada Caroline Dust, lived at 510 Egerton Street in London, Ontario, and then at 72 Rectory Street (also in London). He had two years of previous military service with the “Tower Hamlets Volunteers.” His regimental number was 123035. His record notes that he had a “slight defect, left eye” and he weighed 140 lbs. His “habits” were noted as “Good.” There is no record of any hospitalizations in his file.

Dust went overseas with the 70th Bn, embarking on the S.S. Lapland on 26 April 1916 and disembarking in England on 5 May. The 70th was destined to be broken up for reinforcements, and he was taken on strength with the 19th Battalion on 29 June 1916. He proceeded to the unit on 12 July and joined the unit on 15 July.

On 29 July, near the end of a marathon 16-day tour in the lines, four officers and 34 other ranks from 19th Battalion executed an audacious daylight trench raid. This was the first daylight raid by the Canadians and possibly the first along the entire British front, for raiding up to that point had been carried out exclusively at night. Making skilled use of the terrain in No Man’s Land, which afforded excellent cover in their sector, the raiders penetrated the German trenches just south of the Ypres-Comines Canal at 8:55 a.m. When it was over, they had killed or wounded an estimated 40 to 50 Germans, gathered intelligence on the enemy positions and garrison, and destroyed two machine-gun posts. In the process, the raiders incurred “slight casualties” numbering between five and eight (according to various reports). Coordination with covering artillery had been excellent, and the efforts of the gunners were vital to the raid’s success. By daring to raid at an unconventional time, the 19th Battalion contributed to the German view that Canadian troops were dangerously unpredictable.

Records do not show that Pte Dust participated in this raid. His personnel file has “Killed in Action” written on it. A notation in it says it was “on the night of 29th July,” leading to the assumption that he died in an artillery attack. Regimental Historian Dr. Robert L. Fraser researched the circumstances of Pte Dust’s death in November 2018. He reported as follows:

I have read carefully through the War Diary from mid-July to the first few days of August. There are no casualties listed on the 29th other than those from the early morning raid. There are continuing reports over the day, and although the day was “quiet,” the report for 6:30 p.m. notes whiz-bangs and high explosive artillery against trenches 26 and 27 and a few other areas. At the moment, my presumption is that [Pte Dust] was killed by an artillery attack.

Further research was undertaken by Dr. David Campbell, author of It Can’t Last Forever: The 19th Battalion and the Canadian Corps in the First World War, who was unable to find any additional information that shed light on the circumstances of Pte Dust’s death, leaving us with the “reasonable conjecture” that he died in an artillery attack during the evening of 29 July 1916.

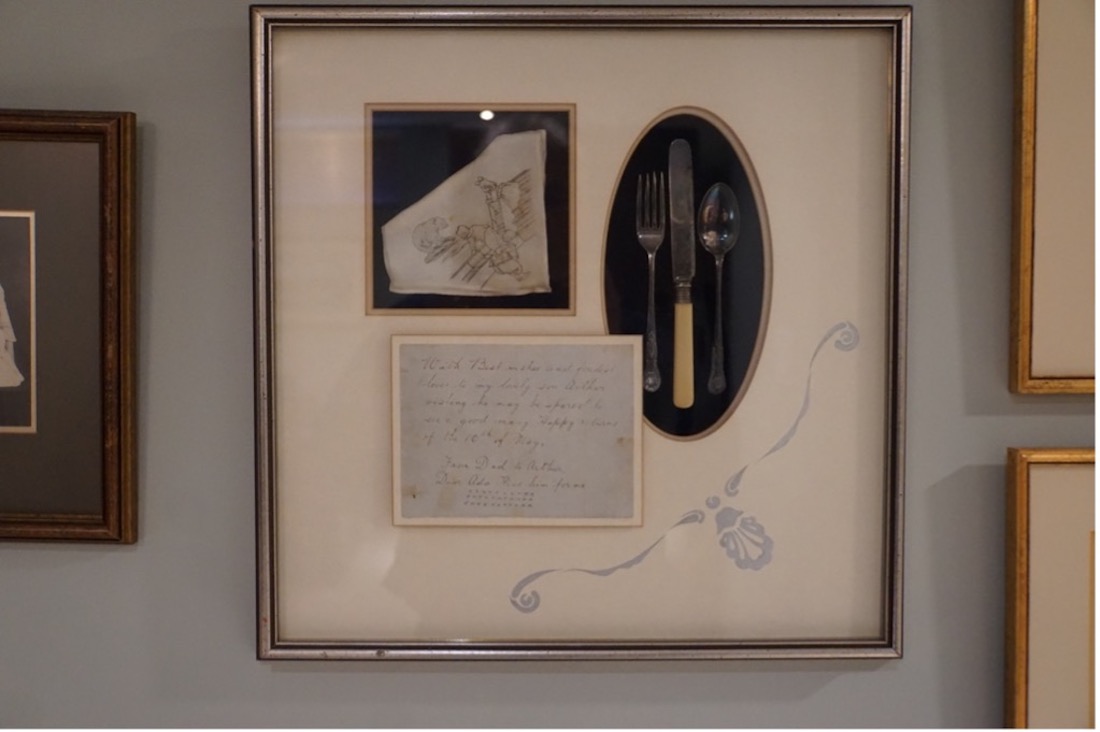

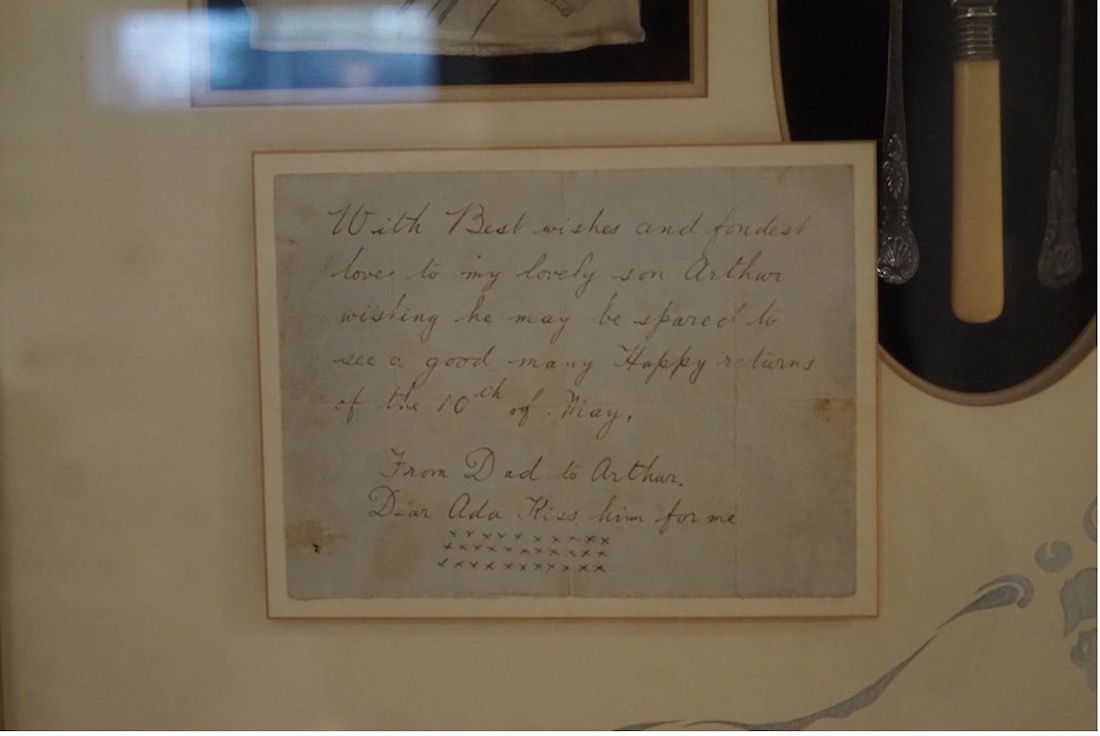

He left behind his wife and his young son, Arthur, born 10 May 1916. Pte Dust never saw his son. He left him a cutlery set and a note [see figures 2 and 3] offering his “Best wishes and fondest love to my lovely son.” He offered the wish that “He may be spared to see a good many Happy returns” and 30 kisses to be delivered by “Dear Ada.” She went back to England in November 1916 but returned to London in July 1917; she died of tuberculosis in 1938. Happily, Pte Dust’s hope for his surviving son was realized and young Arthur would see a “good many Happy returns.” He raised a family that never forgot. The framed cutlery set and its accompanying note remain a cherished reminder of a father’s love.

Figure 2. The cutlery set sent by Pte Dust to his son.

Figure 2. The cutlery set sent by Pte Dust to his son.

Figure 3. A note by Pte Dust to a son he never met.

Figure 3. A note by Pte Dust to a son he never met.

Figure 1. Pte Dust photograph courtesy of 1st Hussars Museum, London, Ontario.

Figure 1. Pte Dust photograph courtesy of 1st Hussars Museum, London, Ontario.

Figure 4. Pte Dust’s resting place, CWGC Ridge Wood Cemetery, Belgium. The inscription at the bottom reads: “He died that others may live.”

Figure 4. Pte Dust’s resting place, CWGC Ridge Wood Cemetery, Belgium. The inscription at the bottom reads: “He died that others may live.”