Introduction

I have never met Pte Robert Mason, MM, but I feel as if I have known him for the past 35 years. We never had an opportunity to interview him for the Black yesterdays project, but Pte J.N. “Mac” MacKenzie ensured that I read every issue of The Albainn, and there I received my introduction to Bob Mason and his poetry, which I used extensively in Black yesterdays. Through Bob’s poetry, I made the acquaintance of John Anthony Glavin – “from out west.” I have never forgotten because of Pte Robert Mason, MM:

“That fellow by the ditch back there was Glavin … from out west

He came a long and weary way but there he lies at last.”

Thanks, “Bobby!”

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

ALSgt John Anthony Glavin (L 102546) (1922–45)

KIA 20 April 1945

“And now and then we thought about the twinkling of the past,

That happy second of our youth before the war … and why

Man’s reason had forsaken truth ’till this had come at last!”

John Glavin’s Irish forebears immigrated to Upper Canada in the early 1840s, a period of a massive influx of the Irish to British North America. By the late 1840s/early 1850s, the family was in Huron County in Upper Canada. Both parents were born in Ontario. His father, Patrick Anthony Glavin (1889-1956), lived with his family in Middlesex County in 1901, and ten years later was a lodger in Assiniboia, Saskatchewan. He married Ellen Mabel Millar (1890-1979) in Brandon, Manitoba, on 21 June 1912. John Anthony was born on 7 September 1921 on his parents’ farm in Limerick, Saskatchewan.

After completing grade 8 In Lakenheath, he left school in 1934 to work as a labourer on Jack Scott’s mixed farm in Stonehenge. Young John took to farming, hoping to return to it after the war although not with Jack Scott; he had some ambition as well to become a mechanic. The so-called “Dirty Thirties” were tough across Canada, but especially in Saskatchewan. Patrick Glavin was in “ill health,” partially supported by proceeds from the farm” and by John as well. The family was Roman Catholic; John had four brothers and two sisters. He had worked on the Scott farm for seven years when he enlisted in Regina on 27 October 1942.

No sooner had John Glavin signed up than he was granted “enlistment leave with pay” from 1 to 5 November. He was 5’ 10-1/2”, 155 lb, with brown hair and eyes. He had a furlough from 17 to 30 May 1943. Pte Glavin’s training included driver (wheeled) (at Shilo, Manitoba) and driver mechanic motorcycles (Woodstock, July 1943), after which he returned to Shilo in August. In the manner of so many Argyll military careers, there were a handful of minor military misdemeanours as well as two brief hospitalizations (one for scarlet fever at Regina in January-February 1943 and one in England for 10 days in March 1944 for venereal disease – gonorrhea).

Glavin went AWOL for “56” minutes on 27 June 1943, failed “to appear at place of parade,” and “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.” For this combination of transgressions, he forfeited three days’ pay. Back at Shilo in August 1943, he received embarkation leave from 28 September to 6 October. He did not return, however, until 15 October, resulting in a more substantial punishment, the forfeiture of 18 days’ pay. Pte Glavin went overseas on 15 December 1943, arriving in England on the 22nd. He lost five days’ pay in February 1944 for another peccadillo and received more training in August 1944; he took driver’s and mechanic’s courses; he had failed to quality as a driver mechanic on 3 May 1944.

“reality of battle was nightmarish”

The Argylls took him on strength on 23 September 1944; he transferred to the X-4 list (unposted reinforcements) on 6 September 1944. He lost five days’ pay in September for a minor offence (AA10). He went to the Argylls on 23 September 1944 at Boekhoute in a comparatively quiet period for the battalion. Two days later, the unit posted him to C Company, which desperately needed September’s reinforcements. The reality of battle was nightmarish, and its consequences – killed, wounded, and POWs – provided considerable challenges to Argyll leadership and the unit’s ability to sustain itself in battle. From 29 July to 7 September, the battalion lost 84 KIA, including 1 major, 6 lieutenants, and 6 NCOs; the wounded numbered 229, including 3 majors, 2 captains, 7 lieutenants, and 11 NCOs; the POWs were 20, including 1 major, 1 captain, and 3 NCOs. The total was 333 struck off strength between 29 July and 7 September, and that number does not include the sick and the injured!

CSM George Mitchell, C Company’s now legendary sergeant-major, kept a private diary (deliberately written in red ink). It records in terse fashion the effect on his company of casualties (killed, wounded, and battle fatigued), continuous fighting, heaving shelling, mortars, snipers, heat, dust, and dysentery. In one month of battle, the company had been all but obliterated; there were few C Company originals left (those who landed in July) at the end of August.

It had been a long dirty, grim and bloody struggle

Glavin came to a unit grateful for the brief pause in the carnage and preparing itself for what lay ahead. As LCpl John Booth of the Mortar Platoon put it:

It had been a long dirty, grim and bloody struggle from Caen, in France to the Leopold [canal] in Belgium and the clean streets, lively shops, and pretty girls were a welcome sight to us Canadians. The pubs were clean … The girls could sing “Roll in the Clover’’ and it could only have been Canadians who taught them that.

Cpl Harry Ruch, 7 Platoon, A Company, wrote in his diary about the joys of “seeing movies, singing, etc at the pubs and enjoying good meals.” The mobile bath and a change of clothes were also much welcomed after six weeks without either. It was a lull and so much so that C’s second-in-command, Capt Sam Chapman wrote to his wife on 2 October that:

Things are very quiet here [Kerselaar] – so quiet in fact that I washed my underwear + short this morning + if things go on foI’m going to get

me a sponge bath … And it’s high time too. I’ve never been so dirty in my life …

As for the weather, it was “cold and wet.” C Company practised one of the great military arts – scrounging for wood, eggs, apples, and pears.

“Takes a while”

Training was the key for reinforcements, not only for the fighting proficiency of the battalion, but also for the survival of the reinforcements themselves. Maj Bob Paterson, the officer commanding C Company, struggled to lead a company short of officers, NCOs, and men. Lt Harold Place, B Company, said, “It was nothing to go out with a platoon of maybe eight people – which is crazy. Where were the reinforcements? I don’t know.” B lost two company commanders in October alone; one was Maj Alexander Chisholm Logie. Maj Paterson had “no faith in the reinforcements and that’s what I ended up with practically a company of reinforcements, and they were just hopeless … You’d try and train them, [but] we didn’t have any time.” ACpl Burt Eden, B Coy, thought “it always seemed us older guys seemed to get through and the reinforcements didn’t … [they] didn’t have the real training, like. Or maybe it was just their time, I don’t know. But it takes a long time to get to know when you move and when you don’t move and when to put your head up, when not to. Takes a while.”

“How far a European war is from a prairie town!”

Young Pte Glavin proved himself in the renewal of fighting from mid-October through to early November. Glavin saw intense fighting from the Leopold Pocket to the Scheldt. The need for good junior leaders and NCOs was pressing. The fighting was constant, arduous, and bloody through to Bergen-op-Zoom and C Company was in the thick of it. The struggle at the Zoom was costly for C Company. The fighting on the 29th of October was bloody, the situation dire, and circumstances were complicated. The previous day the tanks of the South Alberta Regiment and the soldiers of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment entered Bergen op Zoom. The Argylls soon embussed and travelled west and then north by the main road into the town, where at about noon they were greeted by “cheering civilians waving orange flags.” They stopped at a park and ate lunch. Aside from the “occasional rattle of small arms fire” in the distance, “a real holiday atmosphere reigned.” The sky was blue and cloudless, and the sun shone down “benevolently.” “One would have thought,” Maj Hugh Maclean later wrote, “the war miles away.” Then, “the magic word ‘O Group’ struck apprehension into all hearts and shattered our blissful dream.” As it turned out, the Lincs were held up “by a strongly posted enemy across a ditch running east and west just north of the town.” There was a causeway across it, albeit a badly cratered one with a “huge concrete cylinder placed across the road.” Brigade tasked the Argylls to cross the ditch and establish a bridgehead. They were told that “it could be easily crossed on foot, as it was shallow and narrow.” Whether anyone believed it at the time is another story.

“a real tempest of mortaring”

C Company took up a position on the Allied side of the ditch to provide a firm base and fire support. D Company would cross and occupy the houses on the other side, at which point A and then B would follow. Enemy fire awakened at C’s first movement: 88 mm airbursts followed by “a real tempest of mortaring. Heavy stuff it was, mostly.” C was in position by 1445 hours; D tried to cross as enemy “fire grew in fury.” It soon became apparent that a daylight frontal assault was “out of the question.” C and D came under “heavy” 88 mm and mortar fire, “which kept up steadily for the next 36 hours causing many casualties.”

An attempt by the Carrier Platoon to find a route flanking the ditch proved “abortive,” as did the attempt of one of D’s platoons to cross the causeway. At 0200 on the 29th, B Coy under Maj Armstrong moved up to the ditch, which proved to be a canal full of water. A and B Coys once again tried to negotiate the narrow neck of land on the left while D “would attempt in whatever manner” to get across the causeway and establish positions in the houses on the far side.

“a murderous gauntlet”

A and B got across and moved eastwards towards the causeway, where they encountered grenades and small arms fire. C provided covering fire, and the companies reached the causeway at about 0500 hours and some of D reached the houses on the right side of the street by 0800 hours. Now, A and B had “to run a murderous gauntlet.” With Sgt Dewell of D supporting A and B, the “arduous business of house-clearing was next on the programme.” By 1630, the three companies had advanced sufficiently to allow the engineers to begin removing the concrete cylinder. The “close range state of battle … had now been won. But death by no means stayed its hand.” C Company and the Carrier Platoon were “subjected to torrents of shelling, which became so bad that wounded men refused to leave their slit trench to be carried to the dressing station.” Soon enough, battalion headquarters also came under heavy fire. There was “no great change” through the evening and the companies held their positions. Capts Mac Smith and Bill Whiteside, “with great coolness and imperturbability, organized food and ammunition parties and personally took them across the causeway … Under the circumstances, this was a wonderfully brave act.”

C Company had taken worse punishment than any other

On the morning of the 30th, “their task accomplished,” the Argylls re-entered Bergen op Zoom for “a brief rest.” Maj Maclean wrote: “The cost of the action, won after victory seemed beyond the Battalion’s reach, was very great.” When A, B and D returned to the town on the 30th, their total strength of all ranks was 125, hardly more than one normal company. Although it had not crossed the canal, C Company had taken worse punishment than any other. Death found Argylls everywhere, whether in BHQ or the rifle companies.

“I hate the fucking army”

When the battalion’s life settled down again on 5 November, Maj Paterson’s company again needed good and proven junior leaders and NCOs. Pte Glavin was a reinforcement in September; in early November, he was a veteran. Paterson was desperate for talented leadership. He told a story about Pte John Wagner, an original Argyll from 1940 and a stalwart of C Company. In the aftermath of the fighting at Bergen-op-Zoom, he offered sergeant’s chevrons to Wagner, who protested that he didn’t want them and, in fact, refused them. Paterson retorted, “Then you’ll be a sergeant without them.” “Can the army do that,” was the bewildered Wagner’s startled response. “Yep,” declared Paterson. “I hate the fucking army” blurted the frustrated Wagner. On 7 November 1944, Paterson promoted Glavin lance corporal; young Gavin had proven himself.

The Argylls spent the winter on the Maas River, each company in a different location. Days were cold and clear, or cold and wet; occasionally, there was sun while enemy shelling, mortars, or artillery were frequent. There were still “the little pleasures” – bath parades, movies, and the Sally Anne Teawagon” – that helped “substantially in making warfare bearable.” On 21 December, the battalion moved back to Stokhoek. Argylls hoped for a “quiet” Christmas but were on a two-hour notice to move if the Germans broke through the Ardennes. Battalion headquarters was located in several pubs and civilian buildings, while the companies were “all located on a side road.” There was “great satisfaction … that the otherwise commonplace little village could boast of … running water and electric light.” Christmas dawned “bitter cold and crystal clear.” The commonplace toast was that “all be united with our families and friends on Christmas Day 1945.” There was a proper and “delicious” turkey dinner at noon as well as cigars, cigarettes, and a parcel for every Argyll “courtesy of” the Argyll Women’s Auxiliary. On the 31st, the unit moved to Rijen, where the old year came and went. Mail delivery – a vital link with home for soldiers – had “bogged down.” By 9 January 1945, the Argylls were in Waalwijk. Two days later, they received word of attacks by the Allied tactical air force on the German stronghold at Kapelsche Veer. Its presence loomed larger in the battalion’s consciousness as the days passed. The weather turned colder, there was a snowstorm, the Maas River rose, and there were fighting patrols that resulted in casualties.

Kapelsche Veer – “the grim unreality of it all”

The failure of the Lincoln & Welland Regiment at Kapelsche Veer brought the Argylls into the fight. It also entailed the loss of Lt-Col Stewart, who refused to launch an unsupported attack. The Lincs suffered heavily on 26 January 1945. The day before, Glavin was promoted acting corporal. A Company moved onto the dyke on the 27th; D Company relieved them the following day. The policy of relief was deliberate for two reasons: the biting cold and making it “possible for all the new reinforcements … to get accustomed to being under fire.” By 1300 hours, D Coy was on its position and under heavy mortar fire. The Germans counter-attacked at 2200 hours, driving back the Lincs and D Company. It fell back, dug in, and was in turn relieved at midnight by B. The Argylls suffered 1 KIA and 15 wounded. The “approaches to the two demolished houses” on the dyke “were perfect ‘killing ground’ for the enemy,” as D had learned. On the 29th, C Company had its day on the dyke’s “grim unreality,” as Pte Robert Mason of C put it (see Pte Donald Douglas MacKeracher), “a nightmare.” By the 30th, it was over. On 31 January, the Argylls spent the day “in clearing the battle field of the debris of battle” in “surprisingly warm” weather. At Kapelsche Veer, the Argylls rotated their companies on the dyke. It was a deliberate plan intended to give new reinforcements some sense of “being under fire.”

“I was satisfied that I was working with guys that knew what they were doing”

Lt Doug Cruthers was a reinforcement officer posted to C Company. His first experience of combat came on the dyke. For him, the support tendered his platoon by experienced NCOs was invaluable.He mentioned three from that day on the dyke. Acting Corporal Glavin was one of them:

… there were two houses up on the dike [Rasperry was one of them], and they were still in reasonably good shape. Obviously, they’d been blasted a bit … So I took the platoon headquarters and one section and occupied the house on the right … I had [Cpl J.A.] Glavin with me, so it’d be [Cpl F.] Leblanc and [Cpl] MacDonald in the other … there were peripheral defences out beyond with … two or three slit trenches … and then the road went up in between these two houses … Anyway, and we had taken up some kerosene with us or some gasoline … and we had a little stove … in the middle of the night I said to Glavin, “Why don’t you go over and stick in behind the dike and go up and see if Mac’s got enough oil to keep him warm” – because we had some surplus, eh. But I said, “For Chrissakes, don’t approach this position from the front; don’t approach the other positions from the front; and, of all things, don’t come up that road ‘cause there’s a tripwire across it.” So what does Glavin do? Glavin goes over … and he checks with MacDonald. And somehow – I don’t know whether he got disoriented – but he came up to the position from the front. And there was one little machine gunner right there with the Bren gun. And he had that damn thing – I guess he was probably as green as I was – he had the darn thing on single rounds instead of automatic. So he sees this form coming across … up towards him. And he says, “Well cripes … The orders are to shoot so I guess I better shoot.” So he shoots and one bullet went out and Glavin just kept right on walking, right in. Before the guy found out how to get the thing onto automatic, of course, he saw the shape of his [Glavin’s] helmet and so on, and let him come in …

… I must admit to being apprehensive but not being nervous. And I think not being nervous because I had three corporals that were experienced guys. Glavin, Leblanc and MacDonald were experienced men and they were comfortable with their jobs and, I think, I was comfortable with them … I was satisfied that I was working with guys that knew what they were doing.

“dull and wet”

The early days of February were mild, then “dull and wet,” with a rigorous training program set up by the new CO, Lt-Col Fred Wigle. There were new reinforcements and ranges. There were patrols, a buzz-bomb (V-1 rocket) that hit Waalwijk, and a move to Elshout on the 10th and the old positions along the Maas. The battalion moved to Loon op Zand and then to Boxtel on the 20th. Once again, the Argylls were on notice to move for the coming battle in Germany. At 0230 hours on the 23rd, they entered Germany with a single piper at the head of the long column. “Morale and optimism were high,” wrote the war diarist; it was the “moment that we had waited, hoped and struggled for …” Plans were set for OP Blockbuster with H-hour at 0430 hours on the 26th. “Snuff” force, one of the divisional battle groups, which included C and D Coys, left at 1800 hours on the 25th.

“mortar and machine gun fire were intense”

Because of rain the previous day and soft ground, tanks were “not as much help … as had been originally hoped.” Overcast skies and poor visibility resulted in “lagging” air support. During the morning of the 26th, “Snuff” force, which included C and D Companies of the Argylls, “encountered,” as Maj Hugh Maclean wrote in 1945 at the end of hostilities, “great difficulties in getting forward; mortar and machine gun fire were intense.” By mid-afternoon, they reached their objective. The unit war diarist considered the day “successful and casualties were comparatively light”; he had previously noticed that enemy fire – which had “pinned down” C and D for most of the morning – was “heavy. D Company sustained most of the day’s casualties. [Note: This assessment is by no means conclusive. I am in the process of identifying the casualties by company, and so far, they are mainly in D.] Lt Bill Shields, one of D’s platoon commanders, remembered “the stuff was flying around a bit.” He was “running like hell” with his batman and a corporal; one was hit in the knee, the other “badly wounded” in the groin. They made it to a hedgerow, fired back, dislodging the Germans “from this bloody building,” and “hit one or two of them with the Bren …” D Coy was in close proximity to C because Shields saw Capt Norm Donaldson, the officer commanding C, “lying there.” Lt Reg Cleator, one of the platoon commanders, was also wounded. Command of the company fell to the only remaining officer, Lt Doug Beale.

“Just a lot of Tiger tanks and stuff like that”

“We [C Company] lost all our officers before we got on the first objective,” Pte Alan Rawcliffe of 13 Platoon, C Company, recalled:

Just a lot of Tiger tanks and stuff like that. That’s where Reg Cleator lost his leg. Right then, I was with him. He was on one side of a bush, there were three houses up … [near] the first objective. And we lost all our officers before we got on the first objective.

15 Platoon “under Cpl Dempsey cleared a group of houses,” which netted them a bag of 150 prisoners and 50 civilians. At 2200 hours that night, C and D Companies were relieved: “a hot meal was brought forward … and the men were able to spend a night comparatively free of enemy interference.

“we were getting the hell beat out of us”

On the 28th, the Argylls advanced into the Gap. C Company advanced on the southern side behind A Company. They reached it by 0415 hours, “encountering concentrated MG fire.” “All companies,” the unit’s war diarist reported, “suffered casualties by the enemy’s incessant shelling and strafing.” The German counter-attack on B Company’s position began about 0645 hours [see Lt Hugh John McCutcheon]. Lt Doug Beale recounted:

… we were getting the hell beat out of us with mortars and big howitzers coming in, breaking off great big trees, and we hurried through and got into slit trenches that were there up on the far side of the trees.

“cut the legs off one fellow”

Pte Rawcliffe of C remembered “being shelled all that night.” Pte James Patrick Murray was one of those wounded by high explosive shells:

… they put a high explosive in there and it came back and cut the legs off one fellow, my Bren gunner, hit him in the side of the head and he was cut up pretty bad. I got a piece in my leg … and I walked out.

The next day, what was left of C Company approached a house that was their objective. Sgt Frank McEvoy said, “Jeez, you know, you should put something into that house.” They fired a PIAT round into the house and “got about forty or fifty prisoners.” By “breakfast time” on 1 March, all of the Argyll companies in the Gap had been relieved.

“four days of unexpected activity”

From 1 to 6 March, the Argylls were non-operational. The weather turned colder and CSM George Mitchell, the famed CSM of C Company, returned to the unit on 4 March; his diary entry for the day was brief: “‘C’ Coy.” The next day, “after four days of unexpected activity,” the battalion left the Gap “concentrated in the general area of the woods, waiting for the word to proceed towards Veen.” There was some mortar fire from the enemy, resulting in casualties in C Company. The Argylls spent the night of the 5th “in the woods, exposed to the pouring rain, sheltered in slight trenches.” Mitchell’s diary captures the day in one word: “Active.”

On 6 March at 0800, the forward element of a large, combined arms battle group moved out of the woods near Sonsbeck towards Veen, 6.4 km away. It included C Squadron of the South Alberta Regiment’s tanks and C Company of the Argylls. From that time until 1400 hrs, progress was delayed by mines, the “impassable condition of the ground even for tracked vehicles,” and a huge crater in the road from Sonsbeck to Veen. Lt-Col Wigle ordered C Company to dismount from their Kangaroos and advance on foot. At 1600 hours, with the crater filled, the battle group advanced until stopped “by very heavy machine gun fire, mortar concentrations and SP [self-propelled guns] fire.” It proved “too much” for them to handle. One tank was brewed up, as was a Kangaroo. Wigle went forward at 1800 hours and returned at 1900. Bde ordered him “to capture Veen before first light.” C Company had six wounded in the late afternoon/early evening; there were also two casualties in the Pioneer Platoon.

The CO called an orders group; he had decided upon a night-time infiltration with B and D Companies. The night was dark, the route not reconnoitred, there was no tank support and limited artillery support, the infiltration would follow a creeping barrage (difficult with experienced, well-trained troops and problematic with companies composed largely of recent reinforcements), the outer and inner defences were well fortified, the enemy (paratroopers) was well equipped and determined, and the communications between the companies and tactical headquarters sporadic.

“the ultimate in confusion”

The companies crossed the start line at 0100 hours on the 7th. Coordination with the creeping barrage proved thorny. Although there is no explanation in the documents, elements of C Company took part in the action at Veen; six Argylls from C were killed, wounded and/or captured. It is likely that others from C fought there as well. Lt Alan Earp, who commanded the Pioneers, wrote recently:

I was less surprised than you by the blending of companies, especially at Veen which seems to be close to the ultimate in confusion. I think that any who got separated from their fellows (easily done in that context) would hasten to attach themselves to the next available group of Argylls, of whatever Company. There was some comfort in being with other Argylls.

“more blood and horror than a lifetime should take in!”

After Veen, the battalion had another badly needed respite, more reinforcements, and more training. Again, there was a need for senior NCOS and, as a result, Glavin was promoted acting lance sergeant on 23 March 1945. The promotions brought increases in pay as well; from $1.30 daily as a private to $1.90 daily as acting lance sergeant. It was important to him because he assigned to his mother $23 monthly (over 50 per cent of his monthly pay as a private). Within weeks, with the end of the war in sight, fighting would resume. What Maj Maclean dubbed “the bubble” of “a quiet place” “soon burst” in early April. The fighting between mid-April and the 23rd would reduce the battalion’s rifle companies by about 50 per cent.

In the bleak fight at the Küsten Canal from 20 to 22 April, “our Senior NCOs were the main casualties” observed in a melancholy note that put Glavin among them.

… That fellow by the ditch back there was Glavin … from out west

He came a long and weary way but there he lies at last

He didn’t even have the time to make a last request

His time was up and he lay down just where his fate was cast.

He smiled a little lonely smile as we layed him gently by …

The 20th of April was a “clear spring day.” Brigade had intercepted German wireless communications; they had suffered mightily from Allied “artillery, mortars, and planes” but had been ordered to not to give up vital ground and “NOT to retreat under any circumstances.” About 1100 hours, B and C companies attacked northward. The war diarist wrote tersely of the engagement:

At 1200 hours the two companies had advanced … finding the going to be quite sticky. The tanks still found it difficult to move up in support of the Infantry, and our advance, in which the other two companies joined after dinner, was very slow and difficult.

By nightfall A Company had advanced to slightly below the small river that separated us from Osterscheps, where they were meeting continuous small Arms and mortar fire … Two tanks succeeded in working their way up to support our troops on the ground; one was knocked out by a Panzerfaust and brewed up. Both our Artillery and mortars were active throughout the early part of the night.

“Bad luck eh Bobby?” before dying

At some point, 13 Platoon, C Company, was “retreating” and Glavin “took off with a yell … calling to them … and a Spandau caught him sideway and it cut him ‘till he fell …” “Sprawled out beside a broken Bren,” he smiled “a little lonely smile” and said “Bad luck eh Bobby?” before dying.

“the handsome lad was gone”

The entries of Argyll war diarists take on a fatalistic tone; in battle, casualties are ever present, the names of the dead too many and the next days would inevitably bring more pages to be written in the blood of young men. The battle at the Küsten Canal took the lives of an unusually large number of experienced, veteran NCOs such as Gerald Norman Magee and Earl Kress Eby. Unjust or otherwise, it seemed unfathomable.

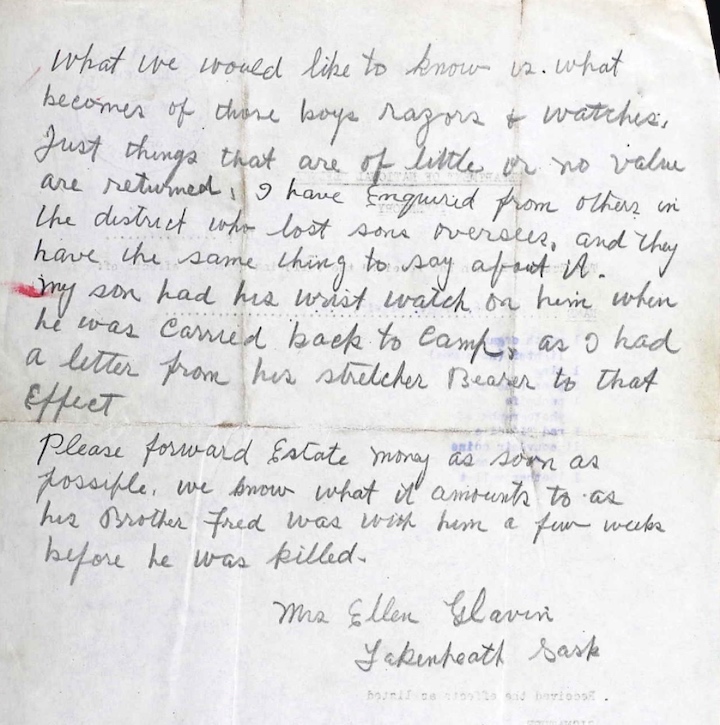

“razors + watches”

The battalion followed its customary rituals for those who “joined the shadowy company of the dead.” The unit’s padre, H/Capt Charlie Maclean, buried them in temporary graves; the piper played “Flowers of the Forest” as a small handful gathered to lay them in the earth. Their effects were gathered and the process, official and unofficial, for the notification of next of kin began. The Glavin family received the life-altering news along with information as to the disposition of the usually meagre estate and the payment of outstanding gratuities. Nelly Glavin wrote to the Paymaster General about her son on 26 May 1945 “to get all particulars concerning” him and alerting them “if you hear from some other one about this [his gratuity] you would disregard it please.” On 15 November, she inquired of the Estates Branch:

What we would like to know is what becomes of those boys razors + watches. Just things that are of little or no value are returned. I have enquired from others in the district who lost sons oversees[sic], and they have the same thing to say about it. My son had his wrist watch on him when he was carried back to camp, as I had a letter from his stretcher bearer to that effect[.]

Please forward Estate money as soon as possible, we know what it amounts to as his Brother Fred [Frederick James Glavin, 1914-80] was with him a few weeks before he was killed.

In time, bodies found their permanent resting spot in Canadian war cemeteries; families lived with their memories and their grief, and life moved on. The Glavins had moved to Creston, British Columbia, by 1951. John Anthony Glavin left his parents, four brothers, and four sisters, two of whom served in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF).

“Red-gold the sun went down tonight behind a cloud-swept rim”

Glavin also remained a poignant memory in the mind, the imagination, and the poetry of Pte Robert “Bob” (Bobby) Mason, MM, C Company. Pte Mason mused on the war over the course of his life, an extended – and poetic – meditation, as it were, on battle, death, good, evil, and the meaning of life. John Anthony Glavin, an Argyll, “from out west” as was Mason, became the subject of a poem titled “K.A. (Killed in Action).”

Poem. Pte Robert G. Mason. C Coy

K.A. (Killed in Action)

Red-gold the sun went down tonight behind a cloud-swept rim…

A solitary row of elms reached up to hide its wrath

The shadows groped the grisly plain … and as the sky grew dim

We saw them spared across the day and sweep it from their path.

And here and there a star came out to wink its steely eye,

And now and then we thought about the twinkling of the past,

That happy second of our youth before the war … and why

Man’s reason had forsaken truth ‘till this had come at last!

We thought of many happy things … like girls and going home…

Of meadow-larks and summertime when life was free from care…

Sweet-fancied and impressive as a lover’s April poem…

And then we thought of Glavin … lying in the ditch back there!

That fellow in the ditch back there was Glavin … from out west.

“Out west” you say? “How far away from where the sun went down?”

A million miles or more I think … no-one has ever guessed

How far a European war is from a prairie town!

Beside a bit of road he lies … and, do I have to tell?

A million miles away, I wonder if they’ll ever know

Of eyes that gazed one moment on a world that seemed a hell

And then the sun was setting … and they never saw its glow,

Sprawled out beside a broken Bren he said “So long” … and died.

A bit of breeze was blowing and it ruffled through his hair.

The ditch was full of water, so we laid him at the side

And walked away and left him … lying by the road back there.

I think he had a girl-friend in some far-off prairie place,

(He often used to speak of her when we were all alone)

Yet I couldn’t help, but lately, see a look upon his face

That wasn’t there when telling of the people he had known!

It didn’t speak of solitude and peaceful countryside;

It didn’t seem to satisfy with thoughts of other days;

It told of seeing fellows swept before a helpless tide

To the slaughtering of humans in the bloody battle-craze…

It told of muddy hours in the midnight on the Maas…

Patrols along the “island” and of outposts in the night,

And I often used to wonder if folks knew just how it was

When they’d think of him and wondered why it was he didn’t write…

For who could tell their mother of the things they had to see

And try to make her understand the horror of it all

When she could only realize the way it used to be

When he was just a handsome lad who answered to her call?

And who could tell their girl-friend that the handsome lad was gone

That the eyes, once full of innocence, were now so full of sin…

From the fields of Arromanches to the Kusten’s misty dawn

They had seen more blood and horror than a lifetime should take in!

And yet … I often wonder! … and I often think I’m right

That even though he never told of all the fear and pain

The very fact he didn’t, made him dearer in the sight

Of those who loved … and waited for his coming home again!

For there’s a truth in fighting that is only plain to those

Who have been, and seen it happen … and were helpless to deny…

When there comes an awful moment to a soldier as he goes

With its sudden revelation … and he knows he’s going to die!

And who can blame a fellow for the things he’s apt to do

When the hand of fate has marked him and he knows the end is near?

If he sit and brood a moment ‘till at lasts the time is true…

Or go rushing into action all oblivious of fear…

Well … he saw his moment coming … and he “went out” just the same

He saw “13” retreating and he took off with a yell…

He ran straight down the roadway, calling to them as he came

And a Spandau caught him sideways … and it cut him ‘till he fell…

… That fellow by the ditch back there was Glavin … from out west

He came a long and weary way but there he lies at last

He didn’t even have the time to make a last request

His time was up and he lay down just where his fate was cast.

He smiled a little lonely smile as we layed him gently by

And he said “Bad luck eh Bobby?” just before he passed away

And I couldn’t help but see a little something in his eyes…

A bit of dream left maybe, … that just hadn’t had its day…!

Red-gold the sun is sinking … but I want his folks to know

That even if the horror of this war will never cease

It’s a kind of consolation just to realize, although

In the fight we never find it, just in dying there is peace!!

Between 18 and 20 April 1945, 9 Argylls were killed in action, 38 wounded, and 2 POWs.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys“In the fight we never find it, just in dying there is peace.”

– Pte Robert Mason, MM

Sgt Glavin’s poppy – “A bit of dream left maybe, … that just hadn’t had its day” — has been placed in the Argyll Field of Remembrance in recognition of Maj W.G. Whiteside, MC, by his family.

Note: The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

John Anthony Glavin

St Marys Roman Catholic Church, Limerick, Saskatchewan, built 1922, dismantled 1976.

Lakenheath community hall, 1927-90.

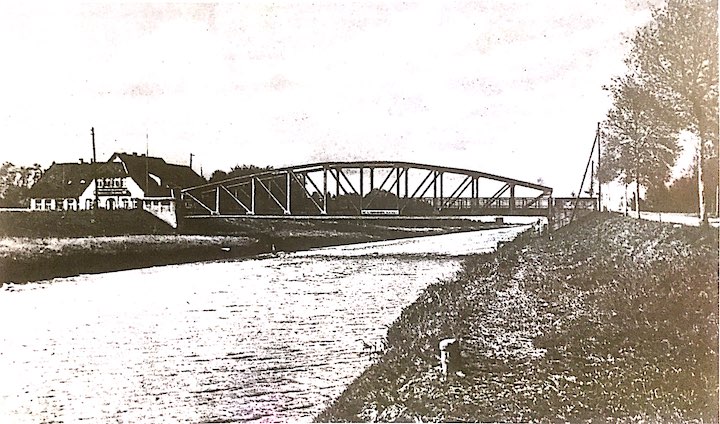

Canal, Boekhoute, Netherlands.

A view of the Zoom during the war. It was expected that the Argylls would walk across it easily.

Site of the anti-tank ditch.

Another view of the site of the anti-tank ditch.

Dragon teeth section of ditch.

The one bridge left intact over the Zoom, blocked by this concrete barrier.

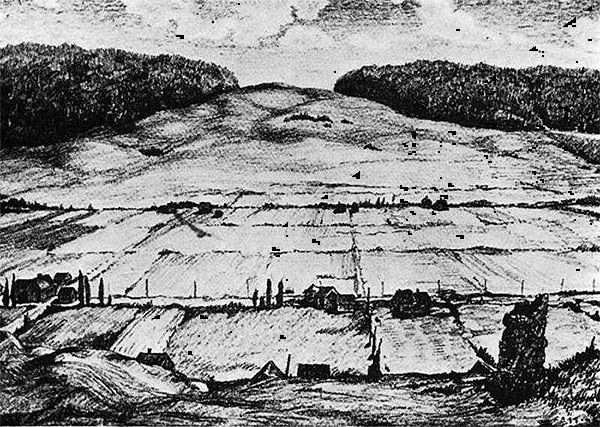

Sketch of Kapelsche Veer by artillery observers.

C Coy digs in with SAR tanks, Kapelsche Veer.

C Coy in forward position, Kapelsche Veer.

Argyll vehicles skirting Sonsbeck, 6 March 1945. Pte Gordon Penrose, C Company, a stretcher-bearer, is standing in the middle carrier facing the camera.

Kapelsche Veer: 15 Platoon reached the top of this hill, where Lt Perkins threw grenades at the house.

The Hochwald Gap, drawn by Brigadier G.L. Cassidy, DSO, ED, based on sketches made on the spot.

Argylls moving forward to Veen, 6 March 1945.

Argylls on Kangaroo, 11 April 1945, Germany.

Crossing site, Küsten Canal.

Küsten Canal, April 1945: after the battle.

Spandau machine gun.

Küsten Canal, 26 April 1945. From left: LCpl M.J. Montague, Pte W.F. Brannick, LCpl R. Templeman, Pte A .Gledhill, Sgt J.W. Boudreau.

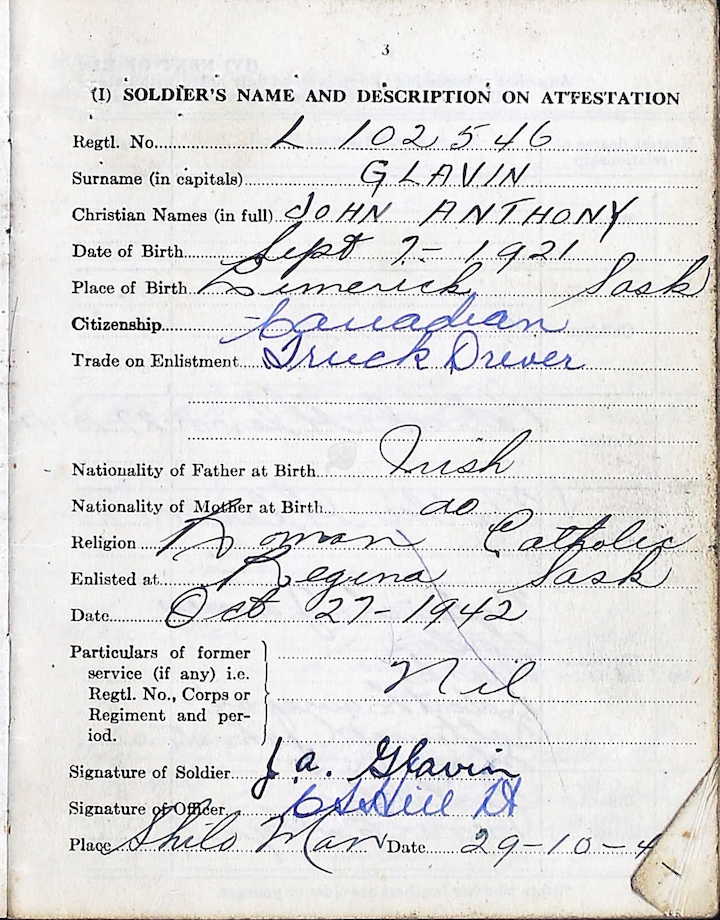

Canadian Army Soldier’s Service Book, John Anthony Glavin.

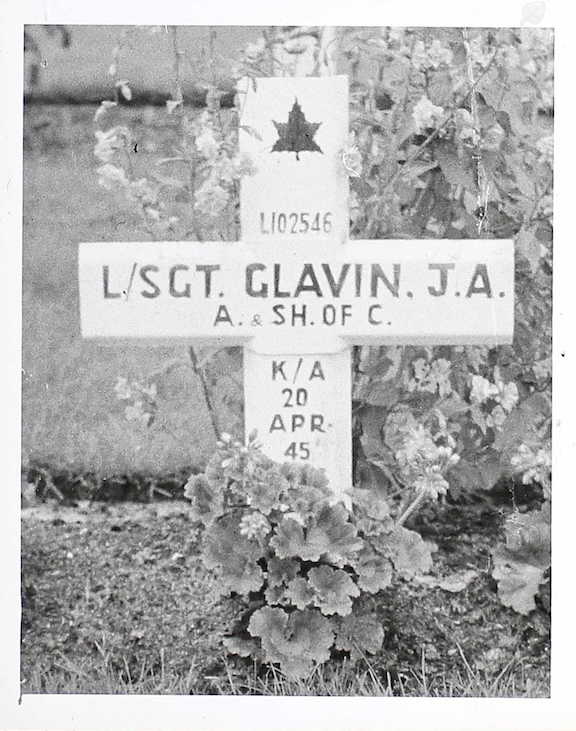

Temporary grave marker, LSgt John Anthony Glavin, Holten Canadian War Cemetery.

Letter from Sgt Glavin’s mother to the Director of Records.

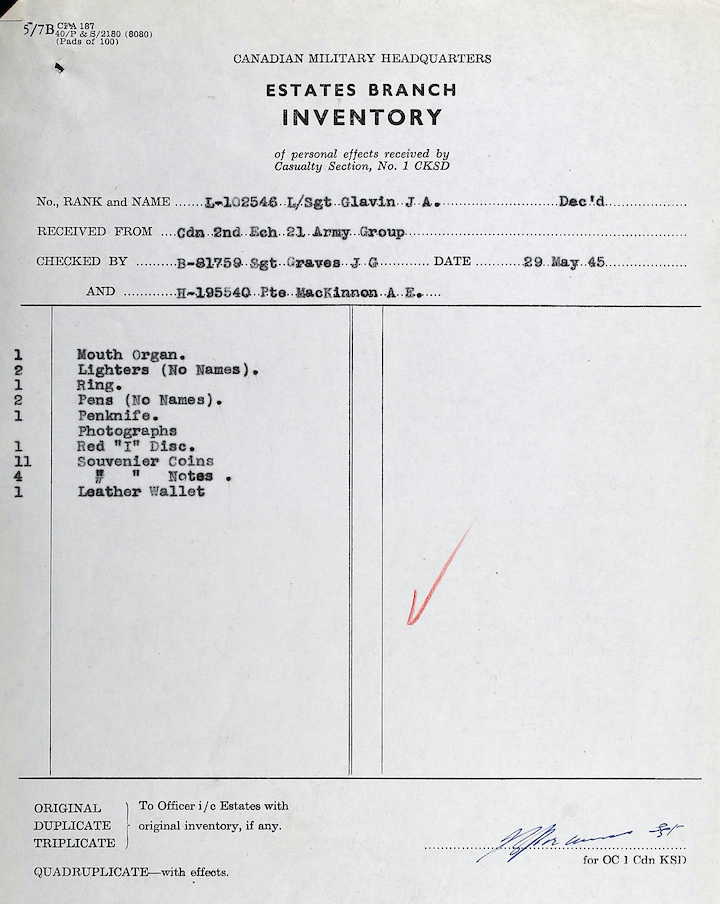

Estates Branch inventory of personal effects, LSgt J.A. Glavin, 29 May 1945.

Gravestone, LSgt J. A. Glavin, Holten Canadian War Cemetery.