Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

Oft-times, I begin the introduction with an indication of my familiarity with the particular name on the Roll of Honour. Not so, this time. At some point over the decades, I must have read Pte Hedman’s name but, if so, I no longer remember.

A query to the Argyll Regimental Foundation’s website spurred my interest. In 2019, Crystal Heskin, wife of Brett Hedman, sent a note about her husband’s great-uncle, Pte Ira Hedman. Her interest and that of her husband:

… started when my daughter [Hanna] was in school and her class was learning about Remembrance Day. She asked if we had any family that served. So we asked Brett’s dad to come over and tell us what he knew about Ira. That’s when I found out our family had very little information on what happened. I was very close with Dell, Brett’s grandpa, and it broke my heart that his uncle that he was very fond of never made it home. I was pregnant with our second daughter, Ember, and my emotions over Ira and the very little we knew wouldn’t let me sleep. So I decided I needed to find out his story.

The path of the Hedman’s family search took them to Flin Flon, Manitoba, where Ira lived for a year. They found him “honoured here in Flin Flon, where many of the Hedmans lived.” I am appreciative of Crystal’s help over the past two years and grateful to Hanna Hedman, whose question set her family on this path.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Hanna Hedman at the cenotaph in Flin Flon.

Pte Ira Harry Hedman (1917–44)

KIA 21 August 1944

Ira Harry Hedman was born in Mazenod, Saskatchewan, on 31 October 1917. His mother, Emma Margreta Söderlund (1877–1932) was “Swedish” at birth and his father, John “William” Hedman (1874–1944), was “American.” They married on 1 December 1897 in North Dakota. The couple had five sons and three daughters; Ira was their youngest son. According to his 1944 military interview, the status of the home in childhood was “Good.” He worked for local farmers “as a young lad” before moving to Flin Flon, Manitoba. Hedman’s Personnel Selection Board file at enlistment provides some of his early background. He completed public school and had one year of high school (“rural”); he left school at age 15 “to work.”

In terms of occupation, Ira Hedman was born and raised on a farm. He was “at home up to age 21 years.” He did “some truck driving, hauling lumber and one summer in garage work as a helper.” There were “Odd jobs as labourer and farm help and one year as an “Oiler in Hoist room.” He worked one year (1941–42) at the Hudson’s Bay Company Mining and Smelting in Flin Flon, making $24 weekly, and had 11 months as a machine “operator helper” (radio drill) at Canadian Westinghouse in Hamilton, Ontario, making $70 weekly.

“loved a good time and was a very comical fella”

Raymond Handyside, of Tisdale, Saskatchewan, was a boyhood friend of Ira’s:

We used to kick around together. He sure loved a good time and was a very comical fella. I remember – he owned a Model T car. It was a small car, a coupe, and he used to come and pick me up to go to dances – he would already have about six people in the car. Then he bought a bigger car and when he came to pick me up, he said, ‘Look at this, I bought one with two perches in it!’

“went to Flin Flon together to look for work”

Handyside said, “Ira and I went to Flin Flon together to look for work – he got a job but I didn’t so I came home.” Ira married Ramona Elizabeth McDonald on 2 May 1942, presumably in Flin Flon. According to a family history, they moved “a short time later” to Hamilton,” where he was a “machine operator” at Westinghouse. The factory was then engaged in “War Work.” His brother, Chester Hedman, and his sister, Violet, lived in Hamilton.

“Called up. Wanted to do his bit”

At his 1944 interview, the examiner asked about his wife’s attitude to his service (a standard question on the form). The entry reads: “Acceptance.” He enlisted on 9 April 1943 in Toronto, Ontario. He was “Called up. Wanted to do his bit.” At the time, he was living at 200 Emerald Street North in Hamilton. He was 5’, 5¾”, 136 lbs, with a “fair” complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair. He had a “Faint scar” on his left upper lip. He had one year of high school in Runciman, Saskatchewan, in 1932.

“responsive, alert and fully co-operative”

Although he was born on a farm and had “4 Yrs” experience on a farm, he had no desire to return to it after the war; his preference was “Motor Mechanic.” The examiner noted:

This married recruit’s training aptitude is high, grade 11. He is responsive, alert and fully co-operative. Has a neat and clean appearance and is of small average build…. His stability seems to be sound and he is of temperate habi[t]s. Sports interests are baseball and skating, likes swimming. His mechanical ability is better than average with a little machine shop experience. Recruit states that he has driven the family car from Tisdale, Sask. to Hamilton, Ontario, no accidents. He has also put in one summer as a garage mechanic’s help and can do minor repairs. He shows an interest in Transport work in Inf. (Motor). High training aptitude, above average mechanical ability and interest indicate suitability for T. Training as Driver Mechanic as quote permits. As there is presently no quota requirement, recruit. Is allocated as a N.T. driver I.C.

The recommendation accorded with the interviewer’s remarks: “Inf (Motor) Non-tradesman Automotive group.

“H.Q. A.G. Secret Radiogram. (Org. 4061) Dated July 13, 1943.”

Pte Hedman was transferred to No. 26 Canadian Army Basic Training Centre in Orillia on 1 May 1943 and was a “Voluntary” blood donor on the 15th. He was granted a “leave of absence” for four days beginning 9 June 1943. On 22 July, he received “14 days furlough.” He was interviewed again at A-11, Canadian Infantry Training Camp Borden on 28 July 1943. This interview is important. It demonstrates the tangible effect of “H.Q. A.G. Secret Radiogram. (Org. 4061) Dated July 13, 1943.” Canadians fought in Italy from 10 July 1943 until 2 May 1945. There were 38 days of fighting in Sicily and almost 3,000 casualties (killed and wounded). It quickly became imperative to get every available soldier in training as infantry reinforcements.

“Due to the exigencies of the service … now being posted to Trained Soldier Company for overseas”

Pte Hedman had “been progressing satisfactorily with Corps Training and should develop into a normally efficient combatant.” However, “due to the exigencies of the service he is now being posted to Trained Soldier Company for overseas movement.” Mona Hedman moved from Orillia to Vancouver as of 13 August 1943; she lived at the home of a McDonald, possibly a relative. The secret radiogram changed the direction of Pte Hedman’s military career and did so almost immediately; he went directly into the infantry reinforcement stream. On 23 August, he was taken on strength as a reinforcement at #4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU).

“not yet completed his advanced training”

Pte Hedman went overseas on 25 August and disembarked on 1 September in the United Kingdom. He was re-interviewed by the selection personnel officer for #4 CIRU on the 9th.

This soldier has been sent overseas after 5 mos. in the Army. He has not yet completed his advanced training. His personality is somewhat immature, but he is a man of marked potentialities. The ‘M’ tests shows No. 4 – 5, on mechanical aptitude and knowledge are very high (57/65), and he claims wide experience in driving and running repairs in civil life. He should do well as driver I.C. or driver mechanic.

Hedman’s stated desire remained unchanged – “Driver-mechanic.” The first recommendation was, however, “Inf (R), rifleman”; the second was “Potential driver.” The exigencies of the service trumped individual aspiration and its connection to post-war preferences. He intended to live in Hamilton after the war.

The Argylls took him on strength on 2 October and he received the full rate of regimental pay, $1.50 daily, as of 9 October. Pte Hedman arrived at Riddlesworth Camp along with 141 other reinforcements at 2000 hours; the battalion itself had arrived at its new quarters at 1530. Hedman was posted to B Company commanded by Maj Don “Pappy” Coons, who signed his two leave passes (seven days on 27 October and another two days on 1 March 1944). As CSM Wilf Stone, D Company, spoke of a reinforcement’s introduction: “I would take them and assign them to platoons, and introduce them to the sergeants, and the sergeants would take them from there and they assimilate them into the company. They would give them background and that type of thing.”

Hedman’s appearance at Riddlesworth coincided serendipitously with that of the Argylls’ new CO, Lt-Col Dave Stewart. He introduced himself at a battalion parade at 1330 hours on the 2nd, delivered a speech emphasizing discipline, fitness, and excellence; and then gave the men “the remainder of the day off.” As one private recalled, he “made a place for himself in the hearts of his men.” Each rifle company had three numbered platoons with approximately 35 soldiers in each platoon; B Company’s platoons were 10, 11, and 12. The number of Hedman’s platoon is unknown. The contours of Hedman’s life during his months in England were marked by company and battalion training, brigade and divisional exercises in the field, movement from Riddlesworth to Uckfield in December, conditioning, route marches, work on ranges, new equipment, and various entertainments. Pte Bill Wingate was in B Company as was ACpl Coningsby Gooderham and ASgt Cecil Fisher. The shape and some of the texture of Hedman’s life in those days is revealed in their biographies. Letters from home were vital to most soldiers. Pte Hedman was with the battalion for 11 months; when he died, he had 10 letters in his personal effects. He was alert, co-operative, attentive, comical, and easy-going.

July 1944 was given over to the preparations for movement to the bridgehead in Normandy (see Lt Milt Boyd). Pte Hedman was in an early party of Argylls; he embarked from the United Kingdom on 19 July and disembarked in France two days later. By the 26th, all parties were there and the unit was reassembling. The scenes of war, the destruction and stench of Caen, the ruined villages, burnt-out vehicles, and the dead provided compelling evidence that war was real. The first casualties, such as Pte Percy Hindle and Pte James Bannatyne gave the reality of battle an Argyll dimension. Hedman was at Bourguébus, where the Argylls endured intense shelling and sniper fire; he was at Tilly-La-Campagne, possibly with 12 Platoon of B Company, which lost Ptes Wingate and Gooderham. In the first week of action, B and C companies had the most casualties. He was with B Company for the battalion’s four-company infiltration of German lines at Hill 195 on the night of 10/11 August. B Company’s OC, Maj Coons, was badly wounded there and Lt Boyd killed.

“to be one of the culminating actions in the battle of Normandy”

There was no respite for B Company in August 1944. On 18 August, the battalion was near Trun. The unit war diarist recorded that:

At 1500 hours “B” Company came under command of the S.A.R. [or, properly speaking, a squadron commanded by Major Dave Currie, OC, C Squadron] to support them in an attack on St. Lambert-Sur-Diver [sic]. This was to be one of the culminating actions in the battle of Normandy. By a road leading eastward through St. Lambert the enemy was sending thousands of vehicles and tanks in an effort to extricate them from the trap. It was the task of our force to seal this gap. At 1600 hours the Battalion was ordered to move to high ground east of Trun. The move was uneventful.

This otherwise unexciting day was marked by the death of Pte Murray Ryan of B company.

“engaged in very heavy but most successful fighting”

On the 19th, B Company was “engaged in very heavy but most successful fighting.” In the morning, B “cleared one half of the town, and then consolidated in the centre.” 10 Platoon, commanded by the swashbuckling Lt Gil Armour, with a small party of volunteers (Cpl S.N. Hannivan, Pte Jimmy LaForrest and Pte W.F. Cooper [Pte H.W. Code’s name is given erroneously in most accounts]), took out a Panther tank near the main cross-roads of the town. This group displayed “warrior spirit” in abundance engaging the tank and its crew with hand-to-hand fighting by Armour, and skilful use of a Sten gun by Hannivan and Cooper’s PIAT by Cooper and LaForrest, “my gunner.”

“enemy artillery shells falling into St. Lambert”

Pte Art Bridge was with 15 Platoon, C Company, which joined the battle group and B Company in St Lambert: “The road was full of wrecked and abandoned vehicles,” he reminisced, “but except for some enemy artillery shells falling into St. Lambert, there was no direct opposition.” During the 20th:

…the enemy attempted several counter-attacks, both in the Battalion area and at St. Lambert, but in each instance was beaten back with heavy losses. A/Major Ivan Martin, O.C. “B” Company and Lt. [Al] Dalphé [Dalpé] were killed during the fighting at St. Lambert. The fatalities occurred in this way: A/Major Martin was conferring with a German M.O. about methods of removing German wounded from our lines; since the M.O. was speaking French, Lt. Dalphé was acting as interpreter. An 88mm. shell landed in the middle of the group, killing Lt. Dalphé instantly, and fatal[l]y wounding A/Major Martin.

Pte Dick Gillespie was a piper attached as a stretcher-bearer to C Company:

The battle at St. Lamberts was just beginning to start and “B” and “C” coy’s took litteraly [sic] hundreds of prisoners but there were many fanatical German troops determined to break through the gap, which resulted in some three days of bitter and vicious struggle. My task as a S.B. during this battle was more of an administrator as we used captured German doctors an[d] troops for stretcher bearers to attend both the Canadian and German wounded.

“Shelling heavy”

CSM George Mitchell of C Company wrote in his private diary:

Join forces with B Coy at St Lamberts [sic]. Casualties heavy, Coy strength 40. B Coy the same. | Shelling heavy snipers all over —

Enemy shelling took its toll on B and C companies during the day and early evening. B Company’s OC, Maj Ivan Martin, and one of his platoon commanders, Lt Al Dalpé, were killed around noon by shell fire and others were wounded. Pte Bruce Johnson was a sniper in B Company:

I was wounded, oh I’d say maybe between seven and eight o’clock in the evening. Like we’d come back, I’d come back into this area where the rest of them were to try and get something to eat … And all at once this shell came in. I think it was an 88. And I took one [piece of shrapnel] right through the chest, and another one through the leg here, got two in there and one through the shoulder here. It’s still there.

And I went down, and back up again, and then I passed out. Before I went down, I could see the blood just gushing out of my chest. I wasn’t sure [if I was going to die]. I was very close to where the rest of them were, like within the same building.

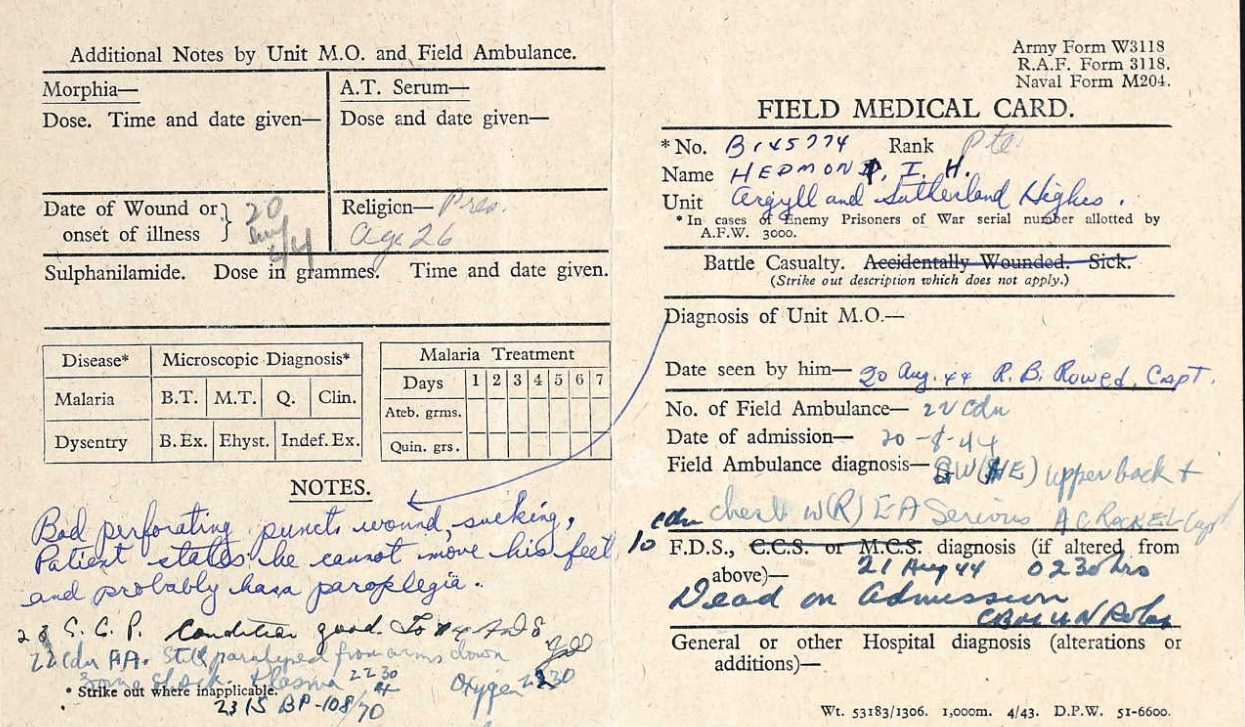

“Bad perforating punct wound, sucking”

It is possible that Pte Hedman was wounded in the same explosion by a high-explosive shell. According to Pte Gillespie, the Argylls accessed a Red Cross jeep to move the wounded to the aid post. Pte Hedman was there in the evening and the medical officer reported:

Bad perforating punct wound, sucking, Patient states he cannot move his feet and probably has paraplegia.

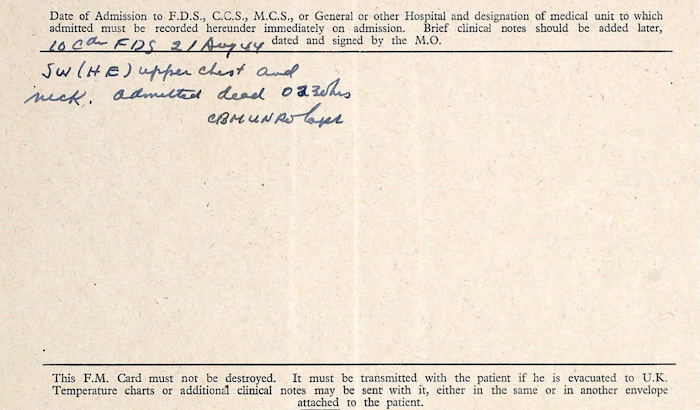

The next note came at 2230 hours: “Condition good. Still paralyzed from arms down. Some shock.” Hedman received plasma and oxygen. 22 Canadian Field Ambulance picked him up for transport: “SW (HE) upper back + chest W(R) EA Serious.” Pte Hedman arrived at No. 10 Canadian Field Dressing Station at 0230 hours on the 21st: “SW (HE) upper chest and neck. Admitted dead.” Other B Company casualties included ASgt Cecil Fisher.

“Admitted dead”

Capt Caleb Zavitz, MD, an Argyll serving officer and vascular surgeon, reviewed Pte Hedman’s field medical cards:

Very unfortunate. Looks like he was hit in the chest, which not only caused a sucking chest wound but also paralyzed him. Presumably had a spinal injury.

A study of casualties and their cause in September 1944 at No. 15 Canadian Field Ambulance (attached to the 4th Division) is revealing: 10% wounded by rifles; 14.5% by mortars; 17.5% by machine guns, and almost 43% by artillery; another 27% were from multiple causes. Artillery fire resulted in more casualties than rifles, mortars, and machine guns combined.

“casualties were high, about 30%, but not unusually high”

The unit’s war diarist wrote on the 21st: the “heavy fighting in St. Lambert ended today” and “the town became the symbol of the utter defeat and annihilation of the German Army.” B and C Coys together had been reduced to “not more than 70 men” and “their own casualties were high, about 30%, but not unusually high, considering that the enemy outnumbered them by 50:1.” None the less, there were casualties.

“All that’s left”

On 22 August, CSM George Mitchell of C Coy wrote in his diary: “stench terrific, death + destruction to Germany.” As for C Coy and his own “gang” of brothers: “All that’s left … is White – and myself.” By the end of the first ten days of September, the old “gang” of the four rifle companies that arrived in France in late July would be almost gone. Of the more than 800 men who had landed, 90 were killed in action, 278 wounded, and 32 POWs for a total of 410 – more than 50% of the unit’s total establishment and about 80% of its fighting strength.

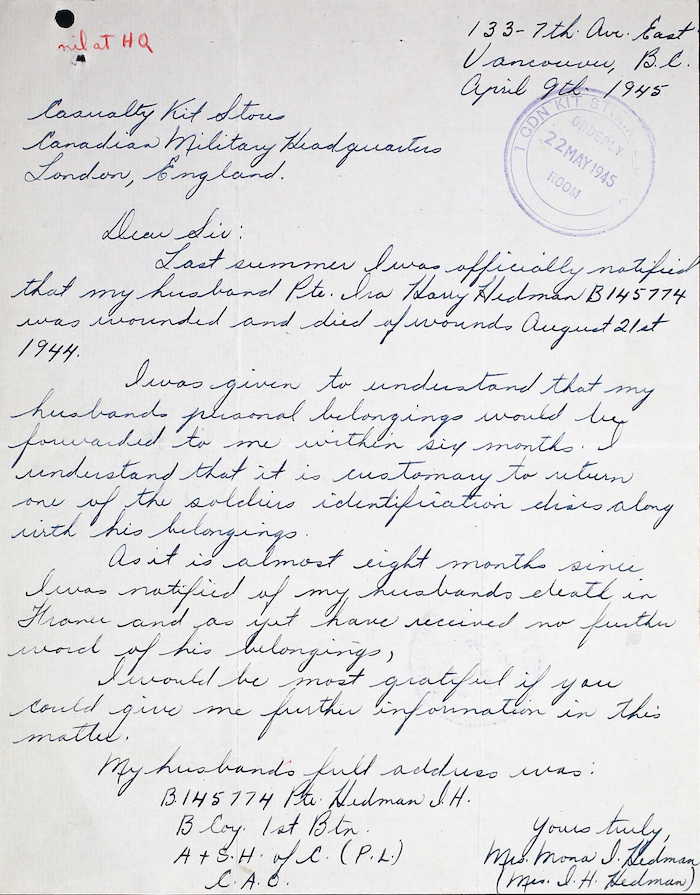

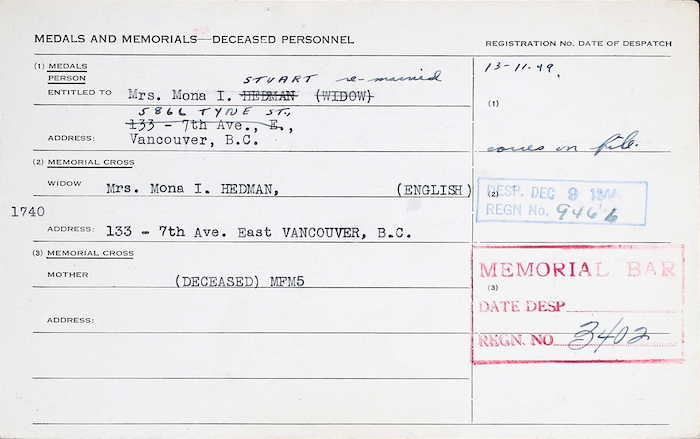

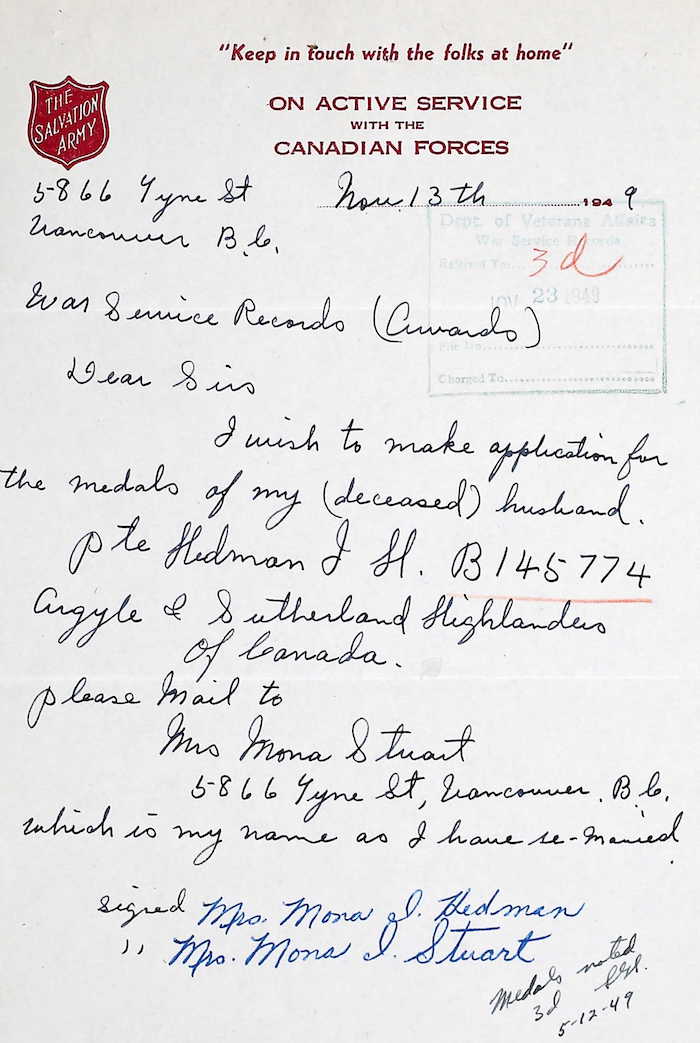

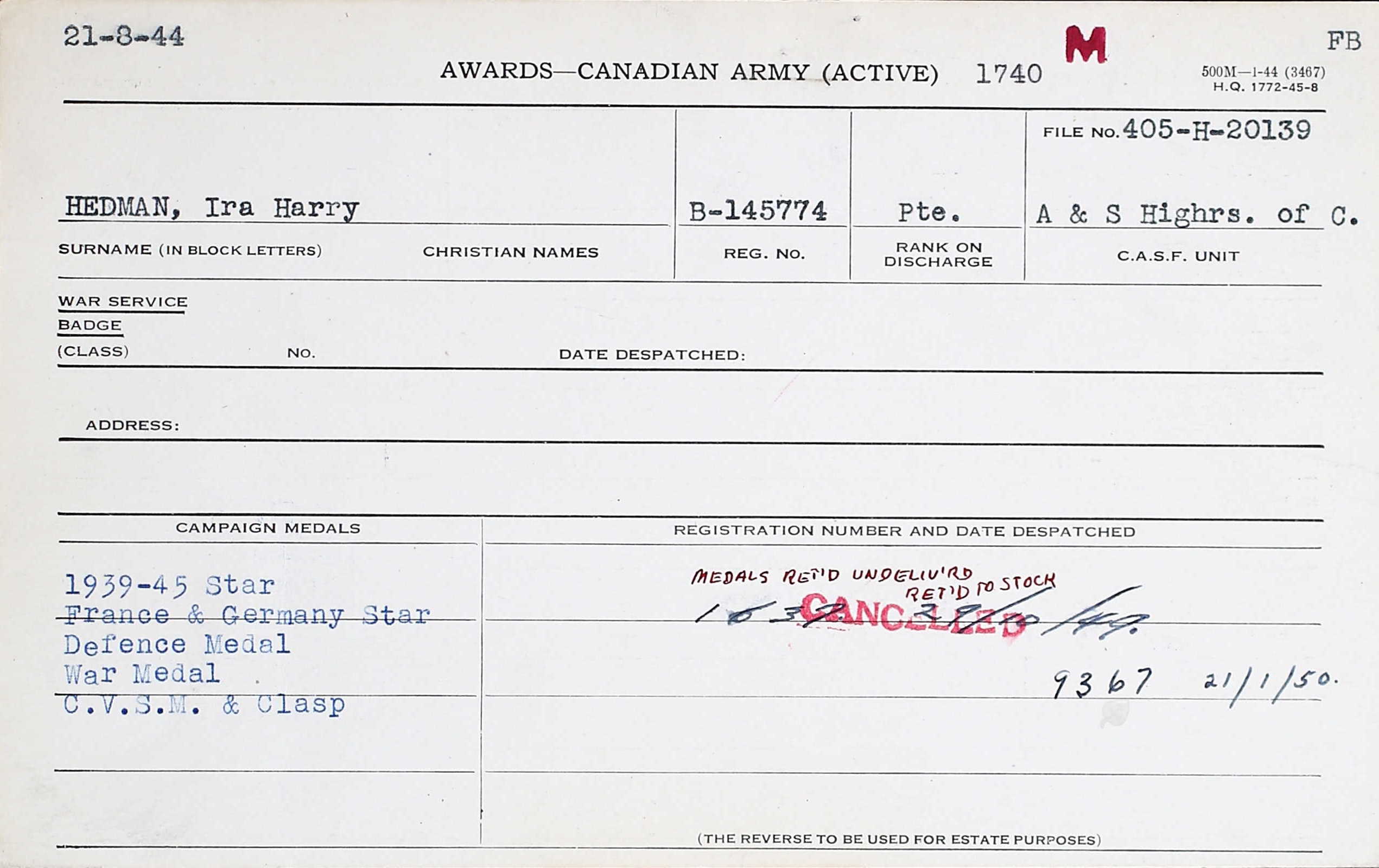

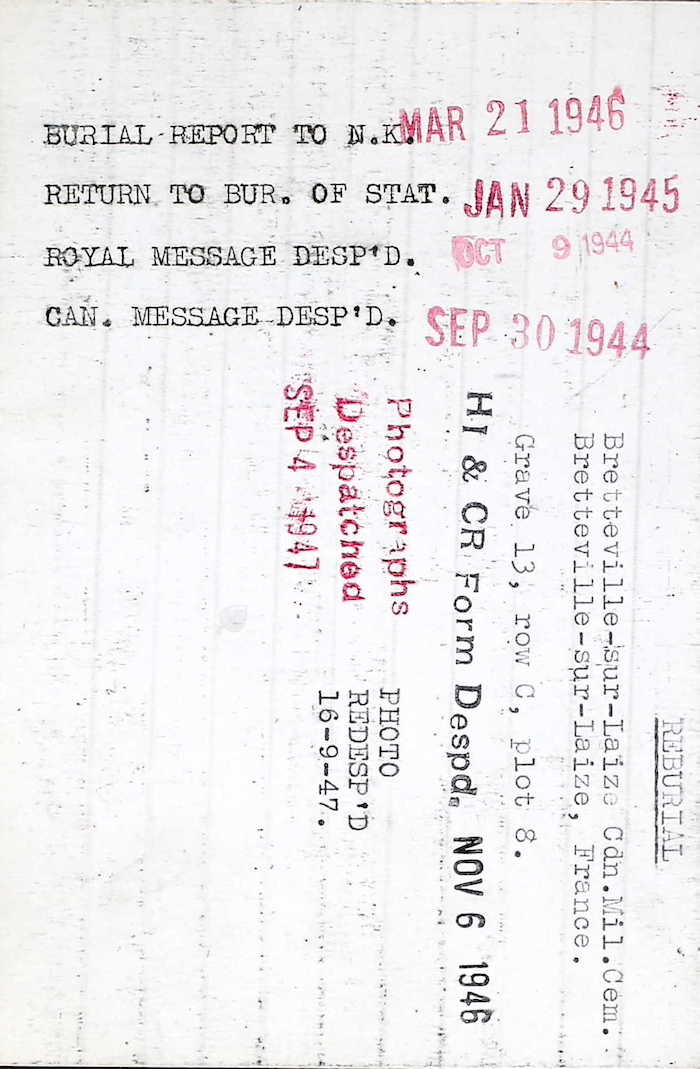

Mona Hedman received the life-altering telegram on 21 August. Like so many Argylls, Pte Hedman had few personal effects: a cap badge, a Glengarry, a photograph case, an address book, photographs, receipts for his 5th and 6th Victory bonds, a tie clasp, a wallet, a writing case, a gold signet ring, a metal ring with initials, an automatic pencil, 10 letters and 2 “snapshots.” He left two insurance policies, one for $500 with Toronto Mutual Life, “who take advantage of War Clauses + only return Premiums,” and one for $1,000 with Sun Life. Mona Hedman wrote to the administrator of estates twice (14 September and 3 October) requesting a death certificate for the insurance company. She wrote again on 9 April 1945, soliciting further information on the whereabouts of her husband’s “personal belongings.” She had expected them within six months and it was now eight months later. Her next letter is dated 16 July. She thanked the estates branch “for the particulars … concerning the belongings and pay account of my late husband …” She also inquired about his 5th Victory bond. Her final letter is dated 13 November 1949, wishing “to make application for the medals of my (deceased) husband … Please mail to Mrs Mona Stuart … which is my name as I have re-married.”

“he was like a big kid himself before he left”

For the Hedman family, the direct memory of Ira faded with the passing of his siblings and parents. There is a picture of him wearing his Argyll Glengarry and another of him with his wife in the family history, along with some memories of friends, but that is all. There does not seem to have been a continuing connection between the Hedmans and Mona Stuart. One memory – passed down – flickers still. Darryl Hedman, Ira’s nephew, “remembers hearing that he was like a big kid himself before he left. Always spent time with the children of the family.” It is a memory that accords with the estimation of army interviewers and boyhood friends. There is a picture of Pte Hedman on the wall of the Royal Canadian Legion in Tisdale, Saskatchewan, and there is a lake, Hedman Lake, named after him in northern Saskatchewan; it is near Reindeer Lake.

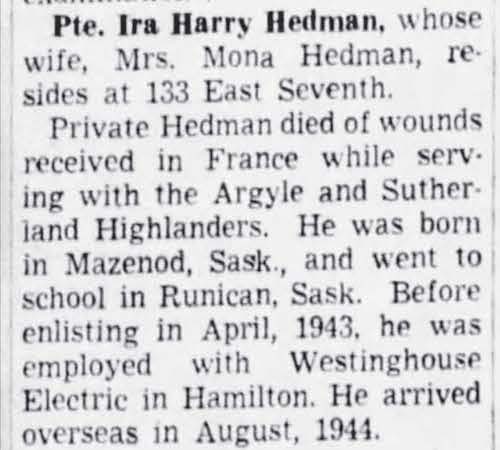

Obituary in Vancouver Sun, 7 October 1944.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Hedman’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Pte Ira Harry Hedman.

200 Emerald Street Hamilton.

Westinghouse plant, Hamilton.

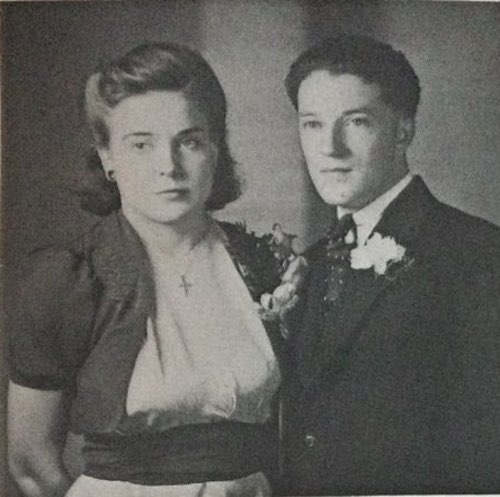

Wedding photo of Ira and Ramona Mona Hedman, 2 March 1942.

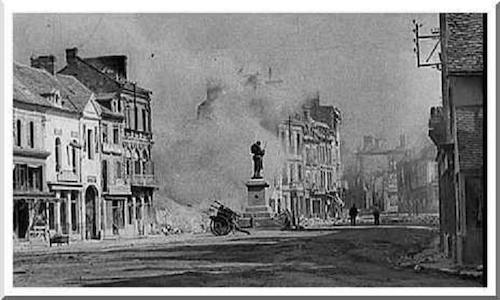

Trun, France – August 1944.

Road to St Lambert, August 1944.

Argylls in St Lambert, 20 August 1944. The Argyll in the vehicle may be Pte W.F. Cooper.

German 88 mm gun.

German 88 mm shell.

PIAT anti-tank weapon.

Sten gun.

Wrecked and abandoned German vehicles at St Lambert, August 1944.

Abandoned Panther tank, St Lambert.

One German escape route from the Falaise Gap, August 1944.

Cenotaph, Flin Flon, Manitoba, which includes Pte Hedman’s name.