Pte Walter Mario Kasurak (1924–44) (A118072)

Introduction

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February this year, I thought immediately of Pte Alex Eli Laba and wondered if the 1st Battalion Argylls had other Ukrainian Canadians killed in action. I quickly found Pte Walter Kasurak from Windsor. I contacted an old friend there, Patrick Brode, who advised me that the Kasuraks were still there and suggested I contact Phil Kasurak. I did and Phil endured graciously my frequent enquiries and entreaties for information. He put me in touch with Walter’s younger sister, Natalie Kasurak Bickerton, and I interviewed her twice. I am grateful to all of them.

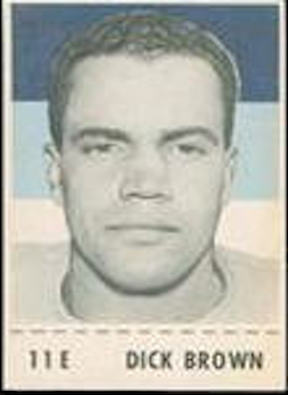

I had been advised by a younger member of the DCB’s staff (everyone is younger from my vantage point, I might add) to try various combinations of a name in Google, which I did. I found Walter’s name in a book by James R. Wallen, Gridiron Underground: Black American Journeys in Canadian Football (2019). To my astonishment, I discovered that there was not only a Canadian Football League angle to Walter’s story, but also a Ticat one. Walter’s best friend, as it turned out, was Pte Dick Brown, a Black American who played for the team from 1950 to 1954. He had done basic training with Walter, was welcomed into the Kasurak home in Windsor, and served in the Argylls with Walter. Both men fought at Kapelsche Veer, and Walter died in his friend’s arms there. I contacted Col Ron Foxcroft CM and Col Glenn Gibson, both rabid Ticat fans and familiar with Ticat history. Their response was immediate and, of course, Col Foxcroft knew Dick Brown and revered him. Col Gibson told me that Dick’s son, Mark, was still around. Col Foxcroft sent him an email and introduced me. I interviewed Mark about his dad and Walter. Since then, Mark (along with his daughter and sister) has provided me with images as well as the transcript of Dick’s journal from 21 December 1944 to 25 February 1945. The entry for 1 February 1945 provides haunting and compelling insight into the death of one’s closest friend in combat. Dick Brown was both Walter’s friend and his comrade-in-arms. Neither he nor the Brown family ever forgot “Mynko” (Dick’s nickname for Walter). I offer my thanks to all of you.

Fourteen Argylls died at Kapelsche Veer; one later died of his wounds sustained there in the United Kingdom. The Lincoln and Welland Regiment suffered terribly at Kapelsche Veer. LCol Dave Stewart considered the attack folly and, apparently, refused to make the attack that fell to the Lincs. He was ordered to go for a psychiatric assessment and, subsequent to it, relieved of his command. Dave Stewart considered command a moral trust and he honoured it. Lt Alan Earp, one of the Regiment’s two surviving Second War veterans, fought at Kapelsche Veer. There is no doubt in his mind as to its essential senselessness.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Emigration is a key and ongoing feature of Canadian history. For Argylls serving in the Second World War, it was quite often an aspect of their lives as the sons of immigrant families. The background to the story of emigration varies from family to family. The Ukrainian diaspora of the late 19th and early 20th centuries provides the backdrop to the Kasurak family. Pte Alex Eli Laba’s family immigrated to Manitoba from Galicia, a province of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in 1898, in search of economic hope and political stability.

“F. Kasurak, teamster”

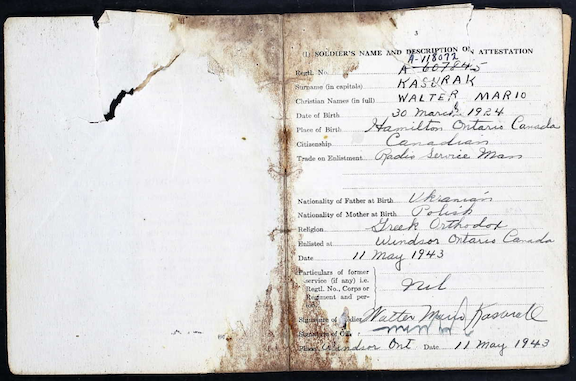

Theodore Frederick Kasurak (1889–1976) was born in Skołoszów (Skolossow), Austria, on 5 February 1889. A Teodor Kaczurak born “abt 1886” in Austria departed Hamburg, Germany, on 7 January 1905 on the SS Pennsylvania, headed for New York. He was single and a day labourer. According to Natalie Kasurak Bickerton, her father immigrated to Canada in 1909 and her mother the following year. Her parents, Fred Kasurak and Mary (Maria) Broda (1892–1980), married in Brandon, Manitoba. According to information in Pte Kasurak’s personnel file, they married on 19 September 1912; their first child, Thomas Kasurak, was born there on 29 October 1912; their second child and first daughter, Valerie, was born there circa 1917. Brandon was a prime destination for the first wave of Ukrainian immigration to Canada. The city directory of 1914 lists “F. Kasurak, teamster,” but it is the only mention of a Kasurak from 1911 to 1923. Walter Mario Kasurak was born in Hamilton, Ontario, on 30 March 1924 [note: one source in his army personnel file has Windsor; two others have Hamilton, as does a family tree]. There are no Kasuraks listed in the Hamilton city directories from 1923 to 1926. Walter’s personnel file notes that he lived in Wentworth for three years (Hamilton is in Wentworth County) and then in Essex for 18 years. Fred and Mary appear in the Windsor city directory for the first time in 1929-30, living at 523 Mercer Street. He is listed as “wks Det.” Windsor’s Ukrainian community was small in 1921, just a little over 200 (the city’s population was 38,591); ten years later, it had grown to more than 2,000 (the city had grown to 63,108), which represents an increase from .51% of Windsor’s population to 3.16%. In 1941, Windsor’s population was 104,415; it was only 17,825 in 1911. The growth was dramatic and the Windsor area, including the border cities of Walkerville, Sandwich, and Ojibway, was becoming the centre of Canada’s auto and parts manufacturing (see Gordon Morton McGregor), a fact that explains much of the Windsor area’s rapid growth within the short span of 30 years.

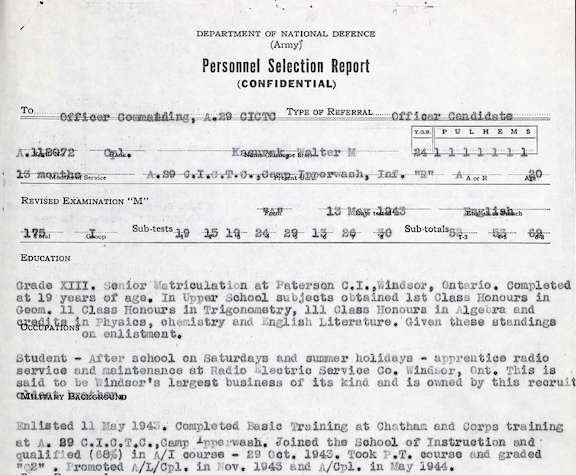

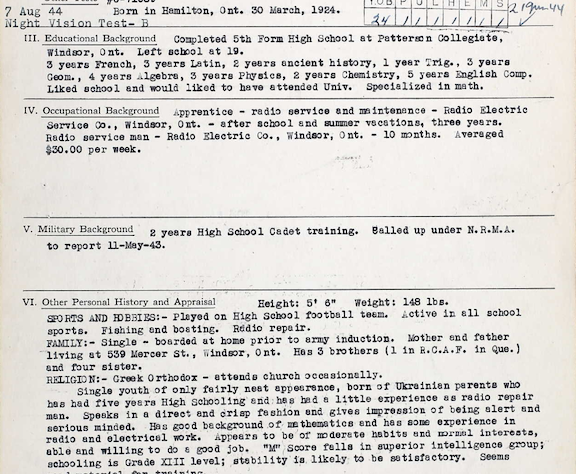

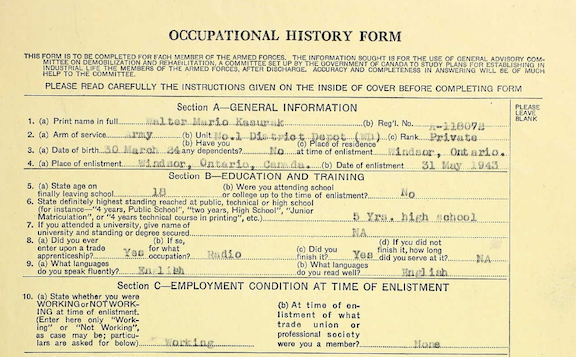

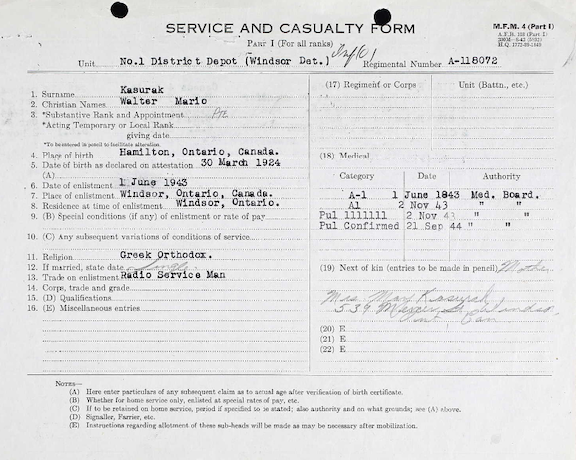

NRMA

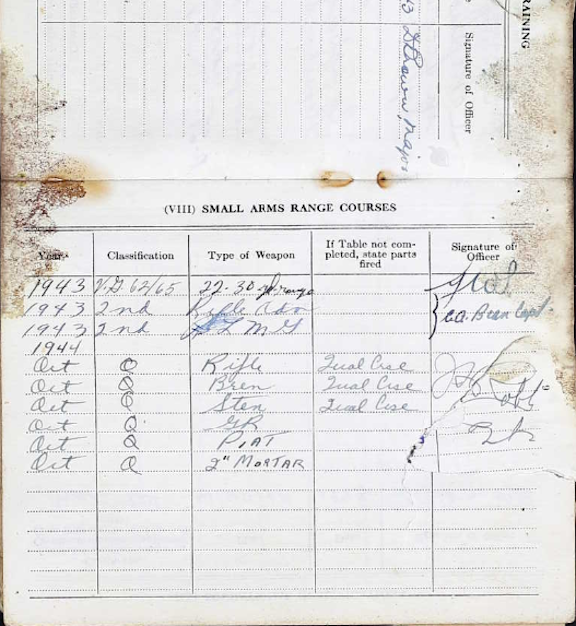

Walter Kasurak’s early years: his education, his interests, his employment, and his recreational activities emerge from the unusually detailed notes of Personnel Selection Board examiners as he moved from enlistment through training. He had National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) service (see Pte Jack Robert Reibeling for a discussion of NRMA) from 11 to 31 May 1943. Over the course of his training, from June 1943 to October 1944, he completed basic and advanced training as well as a “2 week Refresher Syllabus” in late October 1944.

“Radio Service Man”

Kasurak enlisted in Windsor on 1 June 1943. He attended “Course No. 923, ‘D’ Wing, P.T., held at S.3 C.S.A.S. (E.C) C.A.” from 29 January to 18 February 1944 at Ipperwash. He was 5’, 6”, 146 lbs., with a “fair” complexion, blue eyes, and “light brown” hair. Doctors noted that he had a “Slight hallux volgus [bunion] and “Flat transverse arches with slight pronation of both feet.” He had “5 years High School – Junior Matric. Less languages, plus Upper School Maths.” He spoke “English Only” [which was not true]. He left school at age 18 and completed a trade apprenticeship for “Radio.” He was employed by “T. Kasurak,” his oldest brother, for four years as a “Radio Service Man.” Tom Kasurak promised to give him “employment on discharge,” and Walter wished to return to it.

On 15 May 1943, the Personnel Board examiner took particular note of Pte Kasurak. His educational record never failed to impress. Few Argylls had completed grade school, let alone high school. Kasurak had grade 13 with “3 years French, 3 years Latin, 2 years ancient history, 1 year Trig, 3 years Geom, 45 years English Comp.” Moreover, he “liked school and would like to have attended univ. Specialized in math.” Working as a “Radio service man,” he averaged “$30.00 per week.” He spent two years in high school cadets and was called up “under N.R.M.A. to report 11-May-1943.” It was almost certainly the NRMA “call up” that led to his enlistment. He played on the high school football team and was active “in all school sports. Fishing and boating. Radio repair.”

“Greek Orthodox” – “falls in superior intelligence group”

Prior to induction into the army, Kasurak “boarded at home” at 539 Mercer Street. As to his religion, he was “Greek Orthodox” and “attends church occasionally.” He was a “single youth of only fairly neat appearance” who “speaks in a direct and crisp fashion and gives [the] impression of being alert and serious minded.” The examiner mentioned his “good background of mathematics.” He “appears to be of moderate habits and normal interests, able and willing to do a good job. ‘M’ Score falls in superior intelligence group … seems good material for training.” He recommended Pte Kasurak for “R.C.C.S. [Royal Canadian Corps of Signals] – electrical group.”

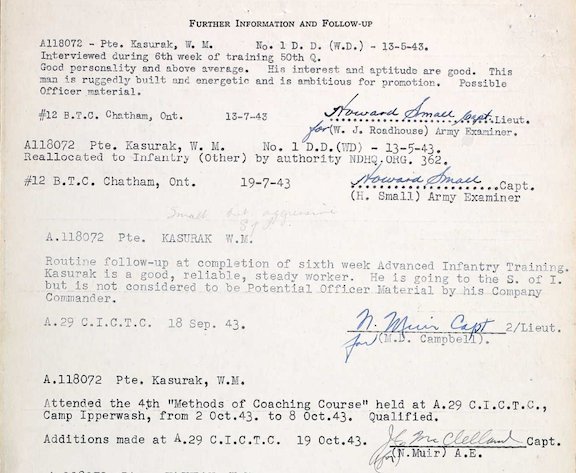

“Possible Officer material”

At #12 Basic Training Centre in Chatham on 19 July 1943, Kasurak made a favourable impression:

Good personality and above average. His interest and aptitude are good. This man is ruggedly built and energetic and is ambitious for promotion. Possible Officer material.

“A first class soldier. Suitable for Overseas Service.”

On 18 September 1943 at A.29 CICTC at Camp Ipperwash, the army examiner – a 2/Lt – described Kasurak as a “good, reliable, steady worker. He is going to the S. of I. but is not considered to be Potential Officer Material by his Company Commander.” He attended the “methods of Coaching Course” held there from 2 to 8 October 1943 and “Qualified.” On 2 November 1943, another army examiner called him “A first class soldier. Suitable for Overseas Service.”

Kasurak attended “Course No. 923, ‘D’ Wing, P.T. held at S.3 C.S.A.S. (E.C) C.A. from 29 Jan to 18 February 1944 at Ipperwash.

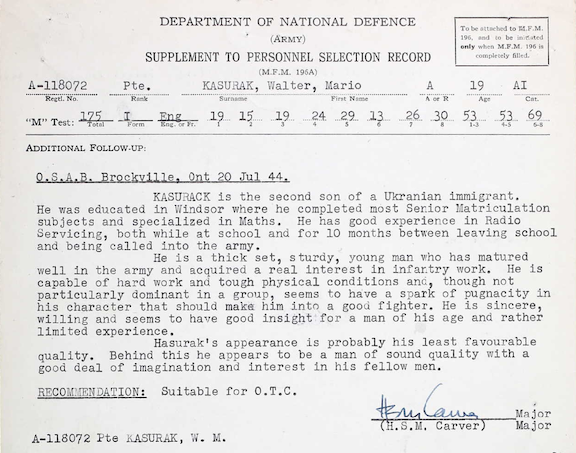

“a spark of pugnacity in his character that should make him a good fighter”

At Camp Ipperwash, Kasurak’s company commander rejected the recommendation from the #12 Basic Training Centre that he was possible officer material. The weight of previous commentary, however, carried the day. In a supplement to a Personnel Selection Record, Pte Kasurak was at OSAB [Officer’s Selection Appraisal Board], Brockville, where a major recommended him as “Suitable for O.T.C. [Officers’ Training Centre].” He took note, as almost all examiners did, of his senior matriculation (grade 13) and specialization in mathematics. He also mentioned his “good experience” in “Radio Servicing”:

He is a thick set, sturdy, young man who has matured well in the army and acquired a real interest in infantry work. He is capable of hard work and tough physical conditions and, though not particularly dominant in a group, seems to have a spark of pugnacity in his character that should make him a good fighter. He is sincere, willing and seems to have good insight for a man of his age and rather limited experience.

“a good deal of imagination and interest in his fellow men”

Hasurak’s [sic] appearance is probably his least favourable quality. Behind this he appears to be a man of sound quality with a good deal of imagination and interest in his fellow men.

The Personnel Selection Report provides quite extensive notes on Pte Kasurak that, at times, either contradicted or elaborated on information in his first interview. In terms of education he had grade 13 and “Senior Matriculation at Paterson C.I., Windsor.” Kasurak’s educational achievements – few Argylls had completed high school – never failed to elicit comments from army examiners. He completed it at age 19. The examiner felt compelled to list his subjects and his marks: first-class honours in geometry, second-class in trigonometry, third-class in algebra and credits in physics, chemistry, and English literature. As a student, after school, on Saturdays, and summer holidays, he was an “apprentice radio service and maintenance at Radio Electric Service Co., Windsor – “said to be Windsor’s largest business of its kind and is owned by this recruit’s oldest brother.” Army examiners found not only Kasurak himself – by dint of educational accomplishment, deportment, and demeanour – worthy of praise, but also his family. His immigrant parents were committed to good education for their children and the children’s accomplishments were obvious. Kasurak’s willingness to enlist rather than remain NRMA was underscored by his comments about his cousin, Walter Edward “Turk” Broda (1914-72). Broda was born in Brandon and played goal for the Toronto Maple Leafs from 1935 to 1951. Kasurak’s mechanical aptitude and inventive impulses also drew elaborate comment.

“Kasurak shows much interest and ingenuity”

Kasurak is [a]quiet type and with good ability. He is Canadian born of Ukrainian parents. The father was a Hydro worker but recently went to Essex County Sanitorium [sic] for treatment. The parents have encouraged and sacrificed much to provide an education for their family — all are getting complete High School education. One brother has a successful business in Windsor, Ont. An older sister was secretary for the mayor of Windsor, Ont. for 4 years and is now doing Welfare Work in Windsor, Ont. Another brother served in the RCAF For 2 ½ years and became Flt. Sgt. Was recently discharged medically unfit.

Kasurak is a first cousin of Turk Broda but calls him a “black sheep” because he remained NRMA. This N.C.O. states he participated only in interform games in High School, because he worked after school hours.

He has restricted acquaintanceship. Had 4 intimate boy friends with whom they built a speed boat. They perfected and installed a fluid drive in it. Kasurak shows much Interest and ingenuity; has submitted two inventions to the Inventions Board, Ottawa, both of which were acknowledged but neither was considered feasible without improvement. One was a gyroscopic principle for motorcycles and the other was an automatic firing device for aircraft.

The commandant at Camp Ipperwash concurred, on 14 June 1944, that Kasurak was a “potential officer candidate.”

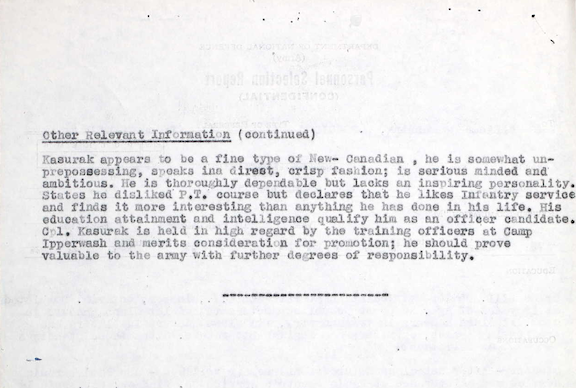

“a fine type of New-Canadian” — “likes Infantry service” – “held in high regard”

Kasurak made a good impression. It is possible that army examiners were confounded somewhat by Kasurak’s evident abilities as a second-generation Canadian. The officer added a paragraph under “Other Relevant Information”:

Kasurak appears to be a fine type of New-Canadian, he is somewhat unprepossessing, speaks in direct, crisp fashion; is serious minded and ambitious. He is thoroughly dependable but lacks an inspiring personality. States he disliked P.T. course but declares that he likes Infantry service and finds it more interesting than anything he has done in life. His education attainment and intelligence qualify him as an officer candidate. Cpl. Kasurak is held in high regard by the training officers at Camp Ipperwash and merits consideration for promotion; he should prove valuable to the army with further degrees of responsibility.

“This man is sold on infantry soldiering”

Pte Kasurak had made steady progress attaining good results and impressing officers at almost every stage. Officer training, however, proved too much, and the explanation for his failure probably derives from his personal circumstances and those of his family. For his part, Pte Kasurak suggested that he “was discriminated against because of nationality and background.” Whether the accusation is true or not is unknown. There were issues with his family’s health and finances, and his responsibility to them given their sacrifice for him. He did OSAB training, “which he completed but was R.T.U. [returned to unit] and TO.S. [taken off strength]… 28 Jul 44, with recommendation that [he] would be better as NCO material, than an officer.”

With a family history of T.B. and 2 members presently in a sanatorium, he is worried considerably, about family finances, as they have sacrificed much to give him his present education. His mother is also in poor health and he is now her sole means of support. There is also the constant thought that he may be predisposed to T.B. himself, especially as he has noticed pains in [his] chest, which he claims are not his imagination.

This man is sold on infantry soldiering, but in view of present health of family, may apply for a compassionate leave to straighten out his home problems but with [a] sensitive nature is concerned about what others may think if this is granted.

While disappointed over his failure, he is not discouraged but does feel he was discriminated against because of nationality and background. With excellent training record and instructional ability, seems suitable for possible upgrading as N.C.O.

As of 28 July 1944, Kasurak received full regimental pay of $1.50 daily. On 2 August 1944, the army examiner recommended that Pte Kasurak be “Placed in Reinf. Stream, to a suitable CIC [Canadian Infantry Corps] Corps T.C.” He received 11 days embarkation leave from 8 to 18 September; presumably, he returned home to Windsor.

“suitability for o/s [overseas] in C.I.C. (Operational) as non tradesman”

Kasurak returned to Camp Ipperwash where on 29 September 1944 another examiner indicated his “suitability for o/s in C.I.C. (Operational) as non tradesman.” He embarked in Canada on 4 October 1944, disembarked in the United Kingdom on the 11th, and reported for duty two days later at 2 CIRU (Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit). On 2 November he was attached to the X-4 list (unposted reinforcements) at 2 CBRG (Canadian Base Reinforcement Group). He left the United Kingdom the following day and landed in northwest Europe on 4 November. Pte Kasurak joined the Argylls on 8 November 1944 at Steenbergen along with his best friend, Pte Dick Brown, and Pte Tom Kedney.

“it was one for all and all for one type of thing, right off the bat”

Kedney remembered his first day with the Argylls well:

… And when I got there, I found the fellows who were still around greeted us with open arms and made us feel right at home … You became one of them immediately and it was one for all and all for one type of thing, right off the bat.

…coming into the Regiment … he [RSM McGinlay] gave us a little bit of the history of the Regiment type of thing, and that they were a very proud group … I can remember him standing out and saying “‘Albainn Gu Brath’ does not mean ‘Fuck you, Jock, I’m all right.’ It means ‘Scotland forever.’” So he let you know right off the bat that this is quite true. But basically, I think they were very efficient getting you off into your company and into your whatever, and getting you started and so on.

…but for the actual things that one sees and one feels and so on [in battle], I don’t think that can be taught back here [in Canada]…

…I don’t think I was poorly trained. I think that I was very well trained, basically. I had attended in Canada a number of courses … So I felt that I had very, very good training. And I think that anybody who trained at Ipperwash, running over those sand dunes, were in pretty good shape when they got over there and were trained very well … I was in early enough [i.e., 1942] that the training was still good … I think that if you volunteer for the service, I think you took everything into the grey matter – what little bit everybody had – and then used it to the best advantage … I think they prepare you as much as they possibly can, but for the actual things that one sees and one feels and so on [in battle], I don’t think that can be taught back here [in Canada].

“I think that hardened me very, very quickly”

On 9 November, the battalion left Steenbergen “in a torrential rainstorm.” Their destination was a short distance northeast of Drunen. The Argylls were in a “holding” position along the Maas River, “the natural barrier separating us and the enemy.” A Company was “south of Heusden, maintaining two platoons in the town at all times as outposts.” The “greatest obstacle to smooth operation was the terrible state of the roads, which had been turned into a vast sea of mud.” A Company had to clean out houses in Heusden, and the memory of it was etched in Kedney’s brain:

…I guess one of the first casualties I saw was in a town called Heusden … they were mostly civilian casualties … We had to clean out houses, I know that. And then we had the job of removing all the civilian casualties from this thing [town hall]. And I can assure you of one thing, there’s nothing more distasteful than the smell of bodies in the decaying state, that have been in there for some time … I think that hardened me very, very quickly.

The Germans “repeatedly shelled and mortared the northern part of Heusden” on the 13th. Kedney recalled one anecdote from A Company’s sojourn in Heusden:

…there was only one bridge going through this town [Heusden]. We were guarding it one day and one of the fellows decided he’d like to go fishing. So he went fishing with a grenade. And it so happened that when they cleared the roads, they had put some land mines in the water and you had sympathetic [sic] detonation … I guess the look on our faces was something to behold. No one ever expected to have that go off. We expected to have a few fish, not an explosion.

“2200 hours ‘A’-Company sent yet another patrol across the river”

The Adjutant, Capt “Mac” Smith, wrote to his wife that the “weather is consistent – always wet, dark, windy and unpleasant.” The same day, 23 November:

…At 2200 hours “A”-Company sent yet another patrol across the river, determined to find out whether or not there were any Germans on the island. The patrol, consisting of one officer and 18 ORs, fired at every conceivable object on the island, including the buildings which at one time had been German O.P.’s, without drawing any enemy fire or finding a trace of enemy activity. After having proved convincingly that the island was clear of enemy – at night, anyway, they returned to our side of the river.

It is likely that Kasurak and Brown were on this patrol. Brown’s journal for this period identifies Lt Herb Maxwell as 9 Platoon’s officer. Maxwell’s recollection of the patrol was vivid:

It was a patrol … to penetrate and find out if we could engage any enemy. I don’t know how many of us went over, and Id just take a rough guess about twelve or fifteen. We went over in a dory. They had a long hawser-type rope tied to the dory, and the Maas was in full, raging flood … I remember that we went over either in two or three trips … we had a local Dutch gentleman row us across. And he was very strong, very capable. What we did, they let the boat out and it ran out … And then he rowed back sort of slantwise across the current until … we got across and we got on the shore. Once we got on the shore, we just let him go and he went down about 150 or two hundred yards down the river and they pulled him up, put the rest of them in.

we got on our bellies in that cold water … and lay there.

…I remember we brought a signaller over. Then we were told that there was going to be an artillery barrage. It was very, very flat land … But up as you went in, about three hundred or four hundred yards – I can’t remember the exact [distance] – it did slope up toward a paved road. And they said that was a crossroads there. I didn’t really see the crossroads well, but they said they were going to bring down artillery fire on that crossroads – and they did. Unfortunately, two of the guns were firing short. Now, one was firing very short. In fact, it was dropping in the river. And the other one was firing short, very near where we were … And down we got on our bellies in that cold water … and lay there. And I kept hoping this damn, one gun would eventually get the message. They didn’t for a long while, but eventually they pounded the hell out of that crossroads.

…we were told to seek out the enemy … So we spread out in a wide arc, about ten yards apart … And I said that we would fire one man at the end, one shot … from a rifle, and wait. Then we’d fire one from the other end and wait. And then we’d fire one here, and wait. And then we’d fire a burst from a Bren and wait. And then we’d fire a burst from maybe the whole group, and then we’d move forward. And we did that, and we didn’t get any response at all … So we went up on the road. And I was a little afraid of the road … I was afraid of the sides of the road, the verges being mined. But we did go up and we went down the other side. We didn’t meet any resistance there. We fired again, and then when I looked at … one of those army clocks or watches you can see in the dark, one of the boys said, “My God, what’s that?” … when I brought it out. It was shining in the light. It was 4:30 in the morning. So we came back, and I reported back to Rupert [Major Fultz, OC, A Coy]. And he thought we had done a good job. I was told afterwards I should’ve gone up into the town…

“We had a real good shot of rum, and we needed it …”

…And I remember the one thing that impressed me was, when we came back, a rum ration had been ordered for our platoon, and there was only about twelve or fifteen of us took part in it. And those other fellows wouldn’t touch that rum ration. They kept it for the twelve or fifteen of us. I thought, “That’s pretty damn good.” We had a real good shot of rum, and we needed it … To me, it was the old troop spirit…

“devoid of any worries … [of] unpleasant aspects of modern warfare”

The battalion left its holding position for new quarters near the little town of Stokhoek on 25 November 1944. The entire battalion was now together for the first time in months, and Argylls were awakened on the 26th “by the cheery playing of the Argyll pipe band.” It was a day, as war diarist Lt Claude Bissell wrote, “devoid of any worries about patrols, ‘Moaning Minnies,’ snipers, and other unpleasant aspects of modern warfare, which had been their constant companion for four dreary months.” There were shower parades, movies, “and a fairly large quantity of beer was purchased for the Men’s Wet Canteen.” Happily, LCol Dave Stewart returned to the battalion after a month’s absence for an operation. On the 28th, Stewart addressed the battalion and lay on a training program for three weeks with an emphasis upon the handling of small arms, and building team spirit at the section, platoon, company, and battalion levels. There were added benefits such as movies, dances, and concerts. As Bissell, observed “even war at times can have its pleasant aspects.” The month ended “marred by a rather widespread and unpleasant case of stomach flu, presumably caused by stagnant drinking water.” There were, however, fewer casualties in November than in any month since July. The respite provided Stewart the opportunity “to instil a new” esprit de corps and “once again make the Argylls into a hard-hitting, efficient fighting team.” The next day A and B companies held a dance with the “music being supplied by one of Tilberg’s hottest swing-bands, who tried their utmost to be ‘hep to the jive.’”

“in readiness to be flung against the Germans”

During a church parade on 3 December, LCol Stewart “made the bombshell announcement that our Battalion was to move back to the former area near Drunen at 0900 hours, 4 Dec 44. The rest period, which had been so carefully and thoroughly prepared … thus came to a premature end.” Back in their hold positions, the various companies set up observation posts. The battalion, under the supervision of Padre Charlie Maclean, held Christmas parties for Dutch children in Elshout. On the 19th came rumours of a major German counter-offensive in the Ardennes. The news of a purported “serious and rapid German breakthrough” occasioned another move the next day. The battalion returned to Stokhoek, where Argylls presumed “we were being held in readiness to be flung against the Germans should they succeed in breaking the American 1st. Army front south of Malmedy.” There were church parades on the 24th, a day that “turned very much colder.” Christmas Day witnessed “spirit and high morale” with Christmas banquets for all the companies – “a proper turkey dinner with all the trimmings” – plus cigars and cigarettes. Every Argyll received a package from the Ladies Auxiliary of the Hamilton-based 2nd Battalion Argylls.

“Well, one bottle of beer this Christmas, but next Christmas there’s going to be a lot more…”

Pte Kedney recalled 9 Platoon that night:

…on Christmas Eve we were all sleeping in the hayloft, and we didn’t know whether we had come close to being the chosen few or whatever, but there was quite a laugh about that. And, of course, on Christmas they gave us what they could … one bottle of beer. And I remember saying to some chums, “Well, one bottle of beer this Christmas, but next Christmas there’s going to be a lot more…”

“I slept in a barn with the cows. Just like Christ in the manger … really nice in that respect.”

Pte Kasurak added a postscript in a letter to his sister, Valerie, on 19 January 1945:

I forgot to tell you that my Christmas was much closer to the real thing than yours could have been. It so happened that Christmas Eve I slept in a barn with the cows. Just like Christ in the manger. It was really nice in that respect.

“very, very cold”

The weather turned colder. On 31 December, the battalion moved in convoy to Rijen and by 2200 hours “most military activity had ceased.” New Year’s Day was “exceedingly cold.” Padre Maclean held a memorial service for fallen Argylls on the 7th. Two days later, the battalion left and moved to Waalwijk; A Company was in the town proper. For Pte Tom Kedney of A Company:

…this was in January and very, very cold. Most of the people didn’t have any coal for their fires or anything like that … there used to be a gas house down the way, and all kinds of coke in it. And we decided that we’re not going to be cold anymore … basically, the whole platoon went down and we decided to help ourselves to the coal for each one of our billets. And which we did. We got the fellow who was in charge of the yard a little bit upset. We told him to bugger off, we were going to have the coal whether he liked it or not, and if he didn’t shut up and get out of the way we’d make sure he did. So we immediately got a lot of bags of coal out of there and put them into the houses that we were all billeted in, and had these people warmed up.

…most of the fellows, if they were billeted at Waalwijk, you’ll find that they were treated royally by these people. And they used to share what little they had with you. In fact, this Willem van Oors … he [later] heard, of course, that … I had been wounded [on 25 January]. And he bicycled from Waalwijk, following me all down the line to the different hospitals, arriving at different hospitals just after I had left. He followed me right into Ostend, where I was there for a day or two … and then bicycled all the way back.

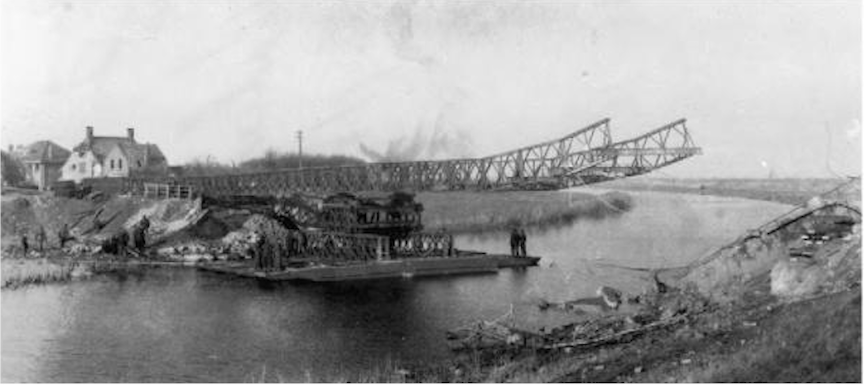

“the enemy-held bridgehead of Kapelsche Veer”

A new – never to be forgotten – place name entered the Argylls’ lexicon on 11 January:

…We were informed at noon that T.A.F. would attack the enemy-held bridgehead of Kapelsche Veer, NW of our position, during the next three days…

Two days later, they learned that British commandos would attack Kapelsche Veer. It failed. At 0130 hours on the 14th, a six-man patrol of the Scout Platoon crossed to snatch prisoners and reached the other side. The Germans countered with flares and machine guns; two Scouts were wounded. On the 19th, there was a “sudden and threatening change to the condition of the Maas River. The water rose by several feet, “isolating our forward outposts.” That day, Pte Kasurak wrote his last letter home; it was to his sister Valerie. He was grateful for her parcel sent on 17 November containing cookies, candy, peanuts, and canned goods. The baloney he noted “was mildewed but after cleaning it up was very tasty.” The “weather at present is really terrible[.]… It[’]s cold a strong wind is blowing and it[’]s raining. Boy what a night.” He had not received any cigarettes “from home but I have some Winchester cigarettes from Betty. You know who Betty is I hope” [a reference to his girl friend].

“They certainly are kind people”

“Things are very good with me,” he wrote, “I am living in private homes most of the time and have a swell time talking to them. Most of them are very kind and usually give you the last food or anything else that they have even if you try to make them understand that you have more than they. They certainly are kind people.”

Walter asked Val to apologize to his sister Irene for not writing. He was pleased that the news from home has been “good. I hope it continues that way. Perhaps in the very near future I’ll be home again and I will be fine again. From the news on the Russian front with the big offensive and the pushing back of the Jerry in the Ardennes gap it looks pretty fair. But who knows. However I have my hopes.” He closed by asking about his younger brother, Alex, and his health.

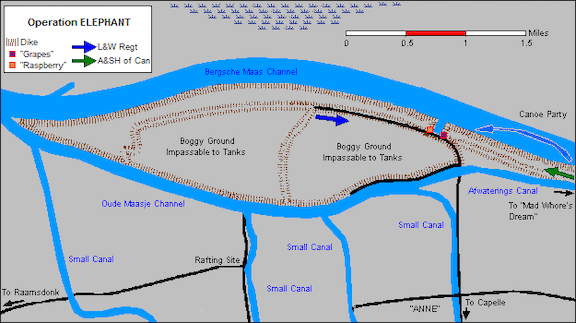

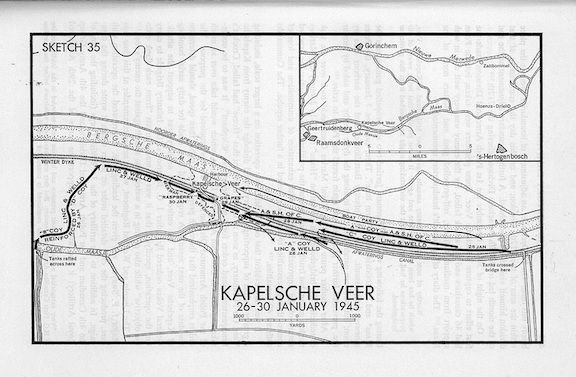

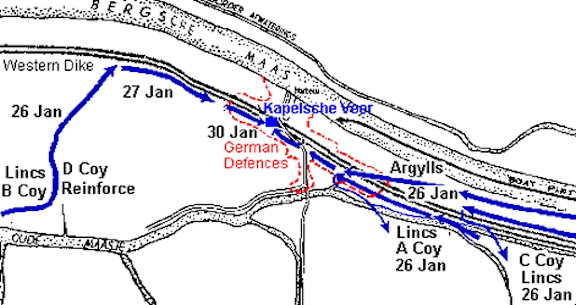

The news of failures at Kapelsche Veer dominated the unit’s war diary. Lt Bissell reported on the 23rd that the Germans had driven back a Polish attack and that the Lincoln and Welland Regiment would “attack the bridgehead, supported by tanks, arty, and flame-throwers as well as a back-door canoe attack. The next day an Argyll patrol skirmished with an enemy, one from Kapelsche Veer, wounding two Germans without taking casualties. A Scout Patrol scheduled for 0600 hours on 26 January was postponed because “there was too much light.” An hour later the area was “engulfed in thick smoke, one of the preparatory steps for operation Elephant” [the attack on Kapelsche Veer].

On 26 January, Lt Bissell, the Argyll war diarist reported “terribly heavy casualties.”

At 0700 hours the operation was launched on a full-scale offensive basis.

Starting at approximately first light, substantial smoke and artillery was laid on. The Lincoln and Welland Regiment was attacking the island from East and West, simultaneously carrying out a back-door attack with what the “Maple Leaf” called “Canadian canoe commandos”. The operation did not run too smoothly at first: The smoke, despite its tremendous quantity, failed to give the proper support in the right spot at the right time. The canoe commandos – also supplied by the L&W Regt – came under accurate S.A. fire from the northern shore, suffered casualties and were forced to abandon the back-door attack.

By 0930 hours, two companies … were on the objective … and for a few moments it was believed that the operation was over. Actually, however, the enemy was hiding in well dug-in slits along the dike and in the basements of the two demolished houses, which made up the settlement … Knowing his men to be immune to mortar fire, the enemy opened up with what battle-experienced veterans described as “the heaviest mortar barrage ever”. The L&W suffered terribly heavy casualties and had to withdraw, leaving many dead and wounded behind.

They consolidated on the west of the island, dug in and prepared for another attack. At the height of the battle, the enemy attempted to reinforce his bridgehead, and launched a boat slightly east of our right O.P. The O.P. detected the enemy despite the smoky haze … and brought a great quantity of 2” mortar and S.A. fire to bear on it. According to the Coy comdr no enemy could possibly have survived in the boat…

Shortly before last light, our “A” Company moved on the … island and dug in … The general plan was now to work up gradually from both East and West and literally dig out all the enemy that were firmed up on the bridgehead. At 2000 hours our forward patrols had edged up … without meeting particular opposition. By 2200 hours, our men, supported by two SAR tanks were well dug in.

“was as unpleasant as possible”

The general atmosphere, cold, windy, muddy and exposed to the elements as well as to enemy fire, was as unpleasant as possible. Rations and rum were taken up to the forward troops under cover of darkness.

The rest of the front was just as cold as Kapelsche Veer, but substantially quieter.

The Lincoln and Welland Regiment lost 4 officers and 25 other ranks killed in the attack. Another 76 all ranks were wounded in action.

Lt Lloyd Grose commanded one of A Company’s platoons (probably 7 or 8; Herb Maxwell had 9):

…we were out on a tank-infantry exercise on this day [i.e. 25 January] … at Loon op Zand. And we were working away, sweating and so on, from running with the troops. And they come out from BHQ saying they wanted a platoon for a firm base for the engineers to cut through the dikes to let the tanks through … which we knew something was coming off. We didn’t know when, but the town of Waalwijk was just cluttered with smoke shells. Every street and every field and that was just cluttered. And so we were picked and we were all sweating and warm, so we came back to our billet, and I said, “Make sure you get a greatcoat on and change your socks. And bring another pair with you,” ’cause the boots were wet and damp from being out running and so on.

So we took off and went up to the small village [Heusden] back of where we were going to go, and they tried to outfit us with white snowsuits. But they didn’t have complete outfits, so we had to take two pair of trousers and put them around our necks, opposite ways [to] cover our back and front. But we had pants on. And this is the way we went in … So we went in at last light, and got across the little back canal. See, that’s what made Kapelsche Veer. And there was a Polish post on the right about seventy-five yards to the rear of us, and we dug in on the dike and made a hole for engineers and we were there by nine o’clock or so that night, dug in and waiting. It was the coldest night of the year, and a lot of chaps, after … working all day and so tired, they just fell sound asleep in the slit trenches and we couldn’t hardly wake them. I didn’t get much sleep that night myself because I wanted to make sure they were alright, to keep them covered when they had blankets on them. But we had chaps in the morning had frost-bitten feet.

…Next thing, there was a tank going over the dike, past us, in the morning about eight o’clock, and the attack went in. They didn’t cut through the dike, they just went in over it. Wasn’t that steep a dike … And the … Toronto Scottish had a 4.2 mortar section off to our left, just across the canal … Then the Lincs and Winks passed through us about 7:30 in the morning … We could see them [in their canoes], ’cause there were windows in the smoke screen, and we saw them picked off by the machine guns from the far side of the river. In fact, we had a couple of 2-inch mortars, [and] we fired some bombs but they couldn’t quite reach the shore…

“we were getting mortar fire ourselves”

…So by eleven o’clock that morning, the [L&W] troops were coming back through us. They had lost their weapons and so on, and they started to congregate around our platoon, where we were on the dikes. And I said, “Move on or you’ll draw fire.” So the next thing I knew, we were getting mortar fire ourselves ’cause they were observed from the far shore when they had stopped. So I said, “Move on. Go on back down” – and they didn’t even have weapons at this stage. They had just dropped them and took off. So they went back and that was it. We were kept there ’till last light at night, and then we were relieved. You couldn’t approach us in the daytime.

On the 27th, the 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade regrouped. The Argyll war diarist took note:

During the night there was comparatively little activity. One “A” Company patrol edged up to the objective … Our company had not yet suffered casualties, which did not make up for the dangerously heavy losses sustained by the Lincoln and Welland Regt.

The cold morning found the situation much unchanged, with both arms of the pincer gradually closing in on the enemy’s bridgehead. The strength of the enemy’s position lay in the intricate underground system of tunnels and communication trenches, which gave the 100-150 Germans the range and scope of a Battalion. The situation remained static all day.

After last light our Infantry moved up still closer to the objective. The enemy was known to be well equipped with “Panzerfausts”, and our tanks showed no particular anxiety to advance within firing range … During the action, we suffered nine casualties, including two officers, and our company was able to advance once more, digging in within a few hundred yards of the enemy.

At least two of the nine casualties were from A Company, including Pte Tom Kedney.

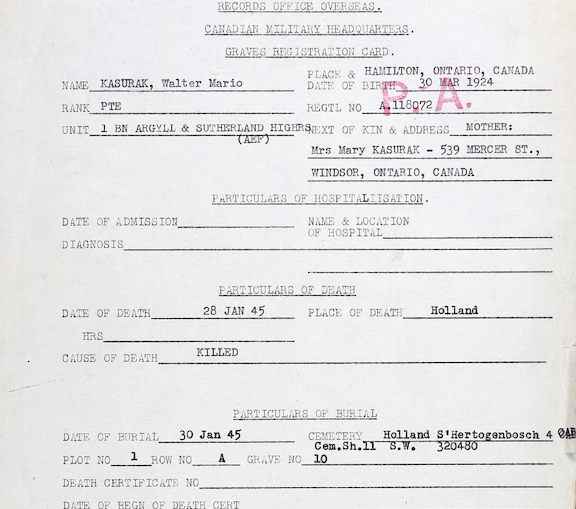

A Company “was almost within grenade range of the enemy,” but there was “little activity on the bridgehead.” At 0330 hours, D Company relieved A “who went back as reserve company.” The rotation had two purposes: first, to limit the number of casualties from frost-bite in the bitter cold, and, secondly “it made it possible for all the new reinforcements in the companies, who had never been up against the enemy, to get accustomed to being under fire…” The Argylls suffered 15 wounded and 1 killed in action – Pte Walter Kasurak (the Lincs lost another 15 killed).

“we got it from both sides”

Pte Kedney recalled:

…just before we were moving out … we were told about where we were going or what we were doing. We weren’t told we were going to Kapelsche Veer, but we were going into a little bit of action and it would take us about seven hours to clean it up.

…I can remember going in or being told about going into this thing. And we had been told … we had taken [Kapelsche Veer] once before, earlier, and had given it over to the Poles. The Poles had lost it … I didn’t know that the British commandos had been in there too and … got the shit kicked out of them. But we were told it would only be about a seven-hour battle and to get it done.

So I can remember going across onto the island. It wasn’t too difficult to get onto the island at that time. We dug in on the morning of the 27th … got up there and my recollection is that we dug in and, of course, we had shelters over top of us and so on. And [then] we moved out. We moved in two sections … and we were the first ones in. And we were following an Alberta [SAR] tank at the time [along the top of the dike], and they got to the point where the Alberta tank commander … thought there was something there and he didn’t want to get hit. So he let off a round at what he considered would be a placement of some type, and it happened to be a lot of phosphorous. So we were basically like daylight … And they [the Germans] let us infiltrate through here, and then … we got it from both sides. [A] Crossfire. And that’s when I was wounded. I was wounded on both sides … in both my legs … I think there [was] twenty-one men. And I think there was something like … one killed and sixteen [fifteen] wounded at that time.

…And then [Pte] Walter Kasurak was killed on the Bren gun beside me. And I remember myself rolling down the dike – which was stupid on my part – rolling down the dike and then behind the tank. And all they needed to do was blow the bloody thing up and I would have gone too … I should have gone the other way. But you know, when you’re thinking … pretty fast to get the hell out type of thing, so you take the easy way out. So it was just a matter of rolling down the hill and in behind the tank … Just total disarray. I don’t think there was any return fire whatsoever…

…I got out about four hours later, I guess. They got us out of there … There was a couple of people, a couple of fellows came in and … were dragging us out because … I couldn’t walk or anything. So I was just hanging on to somebody’s shoulder … and they were dragging me out. And after that, I have no idea what happened.

“there was crossfire coming at us, and my buddy got it right in front of me…”

Pte Jack Smith, also of A Company, never forgot the action that day:

…we got up there … we walked over and there was great big shell holes where we were going up to this last post. There was only the one post left they were holding back, eh. And they threw flares up in the air at us. They let us get right up there near them … when they threw the flares up, there was crossfire coming at us, and my buddy got it right in front of me…

“these guys get to the point where they know something’s going to happen”

According to Tom Kedney, Kasurak had a premonition of his death, and shared it with Kedney:

…I can remember basically going in at Kapelsche Veer with Walter Kasurak, and he said, “I’m scared.” I used to say to him, “Well look, why are you scared? Nothing going to happen to you.” “Well, I’m worried” … I think that he knew that he was going to get it.

…I think everybody has a sixth sense and you may know that it’s your time and that was it. But you know, it’s still hard and it’s very hard on someone if you get someone in this depressed state. It’s very difficult for you when you’re trying to buoy him up a little bit and saying that there’s nothing going to happen. And I can remember that as plain as day, talking to him and saying, “Hey, Christ forget about it. They haven’t got your number,” and so on … [But] these guys get to the point where they know something’s going to happen.

“a German machine gun killed Mynko” – “that is the greatest loss in this war”

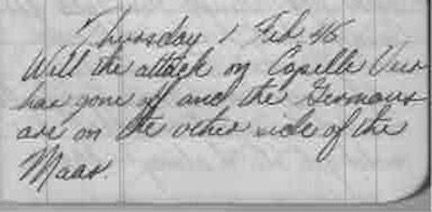

Pte Dick Brown, Kasurak’s friend from basic training to the Argylls and 9 Platoon, A Company, was anguished to the point of despair by Walter’s death. Dick Brown kept a journal for a brief period. They were in different sections of the same platoon. They took in movies together in the days before Christmas and had the occasional “jaw” together. There is no entry for 28 January. On Thursday, 1 February 1945, Dick Brown wrote:

Well the attack on Capelle Veer [sic] has gone off and the Germans are on the other side of the Maas. About four o’clock Sunday morning when 9 ptn [platoon] went into the attack, a German machine gun killed Mynko [Brown’s nickname for Walter]. As far as I’m concerned that is the greatest loss in this war. I couldn’t and still can’t bring myself to believe that he’s gone. I guess I loved him as much as anyone could love anyone. We had such lovely plans for after it was all over and now everything is changed. I just can’t believe it. Tommy Kedney got it through both legs, think he’s good for Canada. Sent his parcel and sent Mynko’s to my house until I see how his sister [Valerie] feels. It didn’t seem to me that he could get it. I always had a sort of feeling that together we were invincible. Always had an idea that other guys got hurt and killed but that it could never touch us. I cried actually, all the way back from the island to the TCV [troop carrying vehicle] in the edge of town don’t remember when I’ve cried before.

“That Sunday morning the 28th day of January 45 changed me to no end”

That Sunday morning the 28th day of January 45 changed me to no end.

When I think back on our times together, how we used to live in the cubicle together, go on weekends fight, I get a lump in my throat that’s damn hard to swallow.

“When Mynko died, so died that invincible feeling within me”

Brown’s journal entry is a searing, poignant, and immediate telling of the loss of a close friend and comrade in arms in battle:

We were lucky that the whole section was not wiped out. That ___ ___ Capelsche Veer [sic] was a tough dirty nut to crack. I’ve had enough now I want to get home bad. As long as Mynko was with me I didn’t care but with him gone I’ve no desire to fight anymore. I’ve lost my nerve. When Mynko died so died that invincible feeling within me. I hope it’s all over soon before we get into action again. Don’t know what do or say to Val [Walter Kasurak’s sister]. Can’t decide whether to go to their house when I get back or not.

Well time will tell.

“Until you’ve been there … you don’t understand the horror of war”

Pte Brown was wounded on 27 February 1945 at the Hochwald Gap. Mark Brown, Dick’s son, said that his dad “never talked much about the war.” He did, however, “remember him telling me [about] being in a slit trench, [it was] shelled, [he] took shrapnel in his shoulder, ear and nose, [he] couldn’t feel his arm. [Walter had] a hole in his back, Dad picked him up and carried him back.” Walter Kasurak died in Dick Brown’s arms. When Mark was a boy, he asked his dad if he ever shot anybody. The reply was always the same: “Son, I never want you to go to fight. I never want you to be in the army.” The memories of battle never left Dick Brown. “It drove Dad crazy, [he] had a drinking problem for a while that was a coping device.” He would “go to the Legion have a few beers” but it “rattled him [to hear] guys talking about the glories of war. ‘Until you’ve been there,’ he said, ‘you don’t understand the horror of war.’” Dick Brown “never really talked about Walter,” even when he got together with the Kasurak family, as they did regularly after the war.

Mark Brown noted that “Walter and Dad did basic training together.” [Walter and his family] were “accepting of Dad and his colour.” Dick Brown did “not talk,” by Mark’s account, “of [the problems] of men of colour in the army, just [later in] football.” Katherine Bickerton, Walter’s niece, noted that “Richard Brown was one of his [Walter’s] closest friends in the army. Mr. Brown (as he was known to me) stayed friendly with my mother’s family even after Walter died, and visited with his wife and children from time to time.”

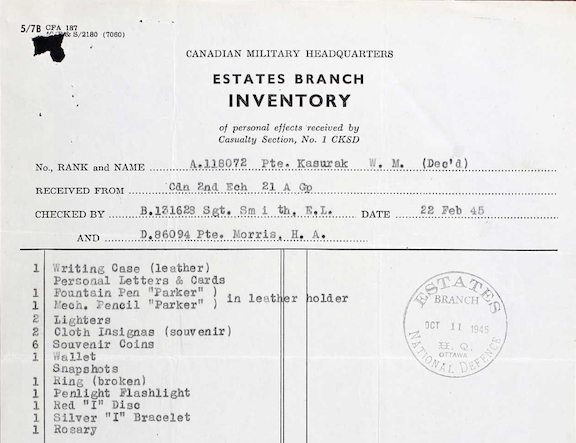

“stacking the fellows – the dead – in the panel truck”

Pte Kasurak was buried in a temporary grave on 30 January 1945. Because of the number of casualties sustained by the Lincoln and Welland Regiment at Kapelsche Veer, it was a different sort of service. Pte Donald Stark, C Company said, “I remember, like they were pieces of wood. Like you looked at it and you just walked away.” HCapt Charlie Maclean, the Argylls’ beloved padre, recalled that “one of the other units had a lot of casualties. We had a few [13 at that point] and we buried them all in a mass grave. And so about three or four chaplains [including Maclean] did it together.” Maclean usually handled the sorting out of an Argyll’s personal effects: a writing case, personal letters and cards, pens, lighters, souvenir coins, a wallet, snapshots, a broken ring, flashlight, a silver “I” bracelet, and a rosary.

“everyone was crying” – “a terrible blow to my mother”

The awful memory of the news of Walter’s death is etched in the memory of Natalie Bickerton, Walter’s youngest sister. “I was actually coming home from Ukrainian school after 4 p.m. Everyone was crying. [I] thought he was missing and he’d be found. Two days later, they told me.” It was “a terrible blow to my mother,” who ended up “in hospital with a nervous breakdown” because of her son’s death. Natalie recalled how much Walter and his buddies loved fishing on Lake Eire, and they had refurbished an old outboard motor boat. Walter “had a girlfriend and they were quite serious about each other, and she was not a Ukrainian. He bought her a watch as a keepsake before leaving for the war.” She remembered:

As a child, I didn’t like to drink milk. This posed a problem for my mother who thought I was too skinny. Walter would challenge me to milk-drinking contests with the winner being the one who could finish a glass of milk the fastest. Of course, he would let me win. I was about 10 years old then, he was 18.”

His closest brother in age, Alex, was confined to bed, due to a spinal injury. Walter would spend hours with Alex playing chess.

At home, all the children “spoke Ukrainian.” It was “the language of the house.” Both parents “spoke English, my dad a little better than my mother, who was at home.” The family attended St Vladimir’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church and “we attended regularly … Dad returned home from work at 5, eat, then Dad went out to help build the church on Hickory Street.”

“We all talked about Walter, all the time”

Walter’s death devastated Natalie and her family. It proved a bitter experience for her mother and affected her health. “My father was heartbroken … We all talked about Walter, all the time.” Natalie still keeps [2022] an 8 x 10 picture “of Walter in uniform in my bedroom.” She kept his letters and put them together in a scrapbook. She gave Walter’s medals to her eldest son.

There was an added element to the family’s grief. Some of Walter’s personal effects, which were not listed in the inventory, were missing. Mary Kasurak wrote to military headquarters [the letter was almost certainly written by her daughter Valerie], advising that “His watch and gold signet ring – gifts from his mother – are among the most valuable and most sentimental articles lost.” There was also “a beautiful gold, pocket size compass” and several leather army cases. She realized “how difficult is [it] must be to recover articles of value during war,” but they represented “a great loss … [of] priceless value to us.” She offered the hope that they could be traced; it is not known whether they were.

“I think of him all the time” and “of course, I’m proud [of him]”

Natalie moved to New Jersey in 1972. In the “late 1980s, my husband and I visited his grave.” It “was very emotional, I was crying buckets.” The cab driver “didn’t want to pry,” but he told Natalie that “he was thankful for what the Canadians did.”

“I think of him all the time,” she said, crying gently, and “of course, I’m proud [of him].”

On his permanent grave marker, the family requested this inscription:

HE DIED THE HELPLESS TO DEFEND,

A FAITHFUL SOLDIER’S NOBLE END

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – the Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion, the Argyll Regimental family, and the Kasurak family.

“a history bought by blood” – Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Note: Pte Kasurak’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Pte Walter Mario Kasurak.

Pte Kasurak and his best friend, Dick Brown, did basic training together and served in the Argylls. Dick Brown would later play for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, from 1950 to 1954.

Pte Kasurak and his best friend, Dick Brown, did basic training together and served in the Argylls. Dick Brown would later play for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, from 1950 to 1954.

Windsor, looking south on Drouillard Road from Edna Street, circa 1930. Courtesy of Windsor Community Archives, PC572.

Windsor, looking south on Drouillard Road from Edna Street, circa 1930. Courtesy of Windsor Community Archives, PC572.

Walter (left) with two of his brothers, Steve and Alex.

Walter (left) with two of his brothers, Steve and Alex.

J.C. Patterson Collegiate Institute, Windsor.

J.C. Patterson Collegiate Institute, Windsor.

St Vladimir and Olga Ukrainian Catholic Church, Windsor.

St Vladimir and Olga Ukrainian Catholic Church, Windsor.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, Chatham, Ont.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, Chatham, Ont.

SS Pennsylvania.

SS Pennsylvania.

Drunen, 1944.

Drunen, 1944.

Heusden, 3 or 4 November 1944.

Heusden, 3 or 4 November 1944.

Heusden, November 1944.

Heusden, November 1944.

Heusden, 1944.

Heusden, 1944.

Heusden, modern view.

Heusden, modern view.

Bailey bridges were constructed in ten-foot lengths and connected together to bridge gaps of up to 200 feet. They were essential to making the connection for troops and tanks to Kapelsche Veer.

Bailey bridges were constructed in ten-foot lengths and connected together to bridge gaps of up to 200 feet. They were essential to making the connection for troops and tanks to Kapelsche Veer.

Bailey bridge erected across a canal.

Bailey bridge erected across a canal.

The Bailey bridge connected the mainland to Kapelsche Veer. It was built by Allied engineers.

The Bailey bridge connected the mainland to Kapelsche Veer. It was built by Allied engineers.

A view from C Company’s forward position on Kapelsche Veer.

A view from C Company’s forward position on Kapelsche Veer.

C Coy digs in with SAR tanks, Kapelsche Veer.

C Coy digs in with SAR tanks, Kapelsche Veer.

Kapelsche Veer: 15 Platoon reached the top of this hill. Lt Perkins threw grenades at the house.

Kapelsche Veer: 15 Platoon reached the top of this hill. Lt Perkins threw grenades at the house.

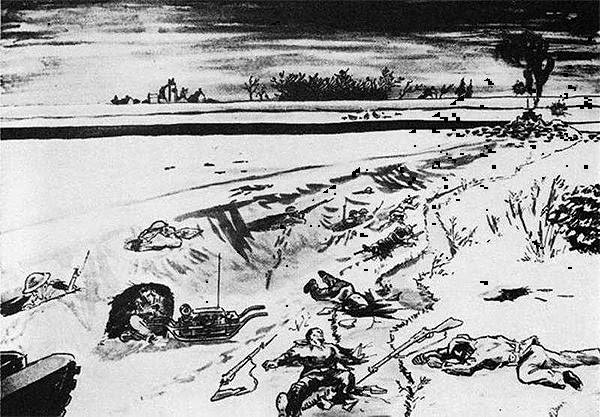

Sketch of Kapelsche Veer by artillery observers.

Sketch of Kapelsche Veer by artillery observers.

Pte Dick Brown.

Pte Dick Brown.

Excerpt from Pte Dick Brown’s journal, 1 February 1945.

Excerpt from Pte Dick Brown’s journal, 1 February 1945.

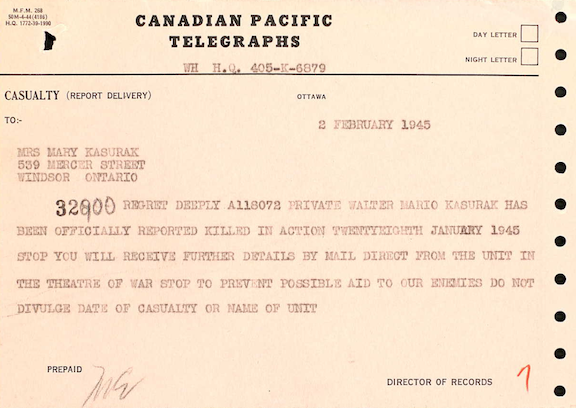

Telegram to Mrs Mary Kasurak, 2 February 1945.

Telegram to Mrs Mary Kasurak, 2 February 1945.

Portrait from newspaper obituary.

Portrait from newspaper obituary.

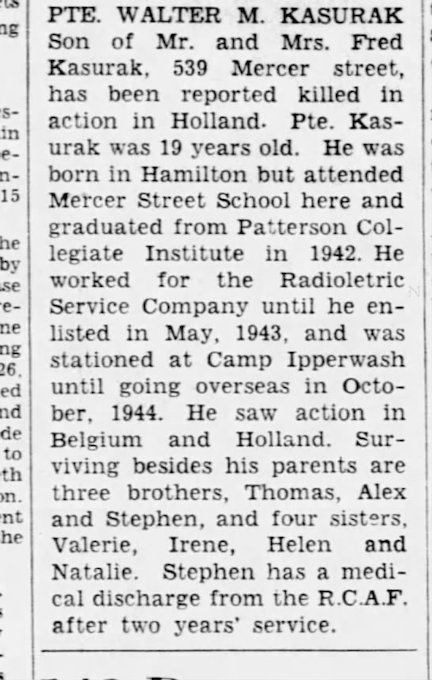

Obituary of Pte Kasurak.

Obituary of Pte Kasurak.

Estates Branch Inventory.

Estates Branch Inventory.

Soldier’s Service Book, NRMA number crossed out.

Soldier’s Service Book, NRMA number crossed out.

Soldier’s Service Book, small arms range courses.

Soldier’s Service Book, small arms range courses.

Groenendall temporary cemetery, 1945, Hertogenbosch.

Groenendall temporary cemetery, 1945, Hertogenbosch.

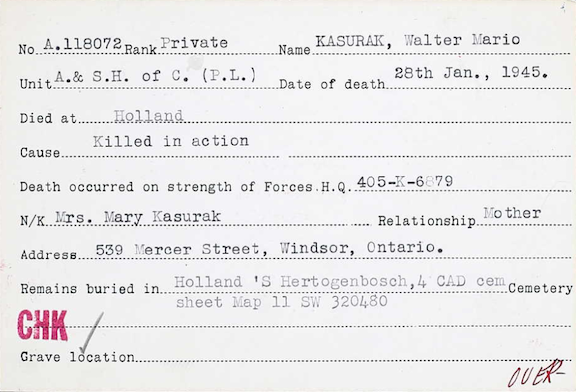

Grave registration card.

Grave registration card.

Burial card, Pte Walter Mario Kasurak.

Burial card, Pte Walter Mario Kasurak.

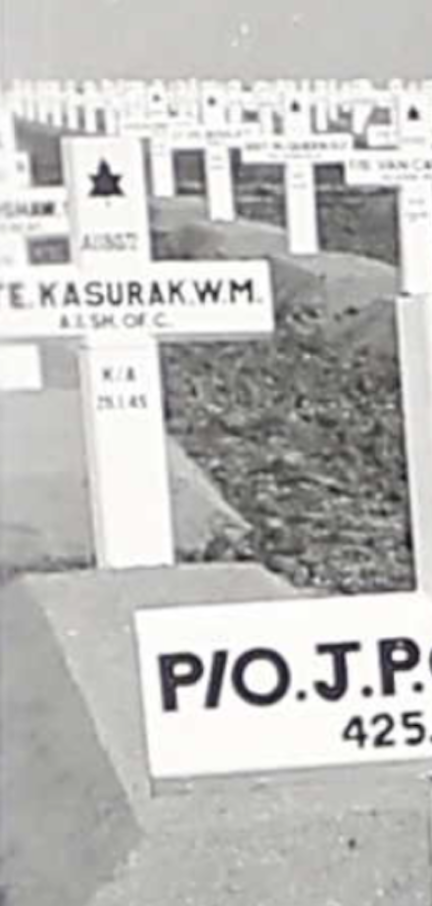

Temporary gravemarker, Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

Temporary gravemarker, Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

Gravestone of Pte Walter Kasurak, Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

Gravestone of Pte Walter Kasurak, Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

Pte Kasurak’s sister Valerie Kasurak, circa 1947.

Pte Kasurak’s sister Valerie Kasurak, circa 1947.