Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

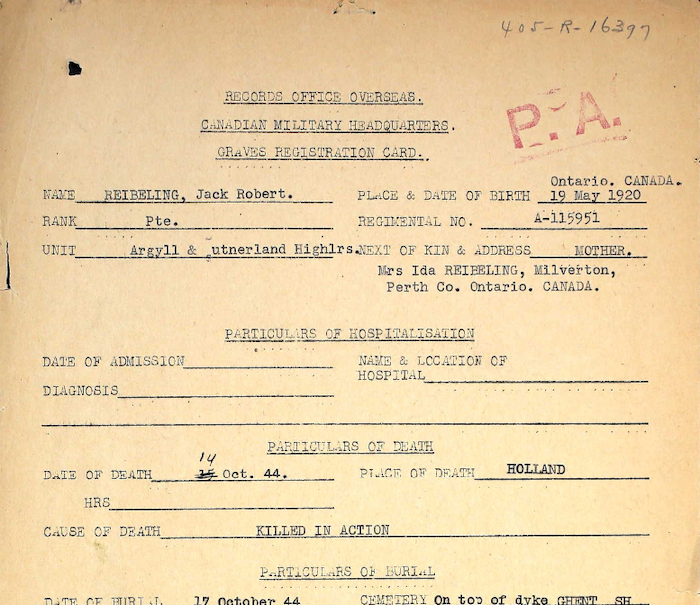

Note on Revised Text: More Information on Pte Jack Robert Reibeling

When I wrote Pte Reibeling’s biography in 2021, I offered my thanks to Pastor Sonja van de Hoef and Administrative Assistant Tricia Holmes Storey of St. Paul’s United Church, Milverton, Ont., for their assistance. In mid-November this year, I received an email from Sonja introducing me to Marilyn Dale, the president of Branch 565 of the Royal Canadian Legion in Milverton. Two days later, I received an email from Marilyn with an attachment containing an image of Pte Reibeling and two newspaper clippings. One contained a transcript written by Capt Malcolm S. “Mac” Smith, the Argylls’ adjutant, to Pte Reibeling’s mother. Marilyn Dale has contact with Jack Reibeling’s nephew, from whom she hopes to receive another image of him and, if she does, will pass it along. Mac Smith’s letter confirms that Pte Reibeling was a member of the Scout Platoon and provides other details. I have revised the biography accordingly.

I thank Sonja van de Hoef and Marilyn Dale for their support in providing more details about Pte Reibeling’s life.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

28 December 2022

Introduction

During last year’s Argyll Poppy operation, I became buried in the daily research and writing required. To the extent that there was a plan, I favoured a chronological approach from July 1944 to May 1945. I hoped to give readers a sense of the battalion in battle, the losses, and their impact on the unit and on their families. Over several months of work, I was struck how casualties in the first six weeks of action transformed the composition of the battalion. At times, I was dumbfounded by the casualty rate of recent reinforcements.

There was always a battle to win, or lose – to borrow shamelessly from Maj Hugh Maclean. But the men fighting those battles from mid-September 1944 on were not the men who landed in France in July 1944. Maj R.D. “Pete” Mackenzie suggested to me, many decades ago, that the tactical brilliance and disciplined execution of the victory at Hill 195 (see Lt Milt Boyd and Pte Paul Cole) could not have been replicated later in the war. I have often juxtaposed his observation with that of Maj Bob Paterson’s. To his mind, Lt-Col Dave Stewart’s best battles were the ones fought from mid-October until his departure on the 25th for an operation. Part of Paterson’s reasoning derived from the state of the battalion: tired, exhausted, bereft of experienced soldiers, and reinforced in September and October by large drafts of replacements. Ptes Alexander Nickoloff and Gordon Douglas Marr were two such soldiers. They arrived in those months and died in October.

This state of affairs became even more pronounced in January, February, March, and April of 1945. Reinforcements from the fall of 1944, such as Pte Donald MacKeracher and LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr met their deaths in the fighting of January and February respectively. I decided to pick an Argyll killed at Veen on 7 March 1945 and selected Pte Wilfred Madaire. By late February and early March, the period between a reinforcement taken on strength and their first experience of battle shrunk considerably as was borne out by the experiences of Ptes Edward Smith and Clarence Vaise, also killed at Veen. Lt-Col Stewart hoped to ease the battalion into battle in late July and early August of 1944. As the unit learned, the boundary of a battlefield was limited only by the range of German artillery as Ptes Percy Hindle and James Bannatyne found out. The battalion learned, as Pete MacKenzie thought, in those days how to endure battle and fight back. Hill 195 offers a stunning, battalion-wide example of what historian LCol Brian Reid calls “warrior spirit.” But Stewart’s warriors at 195 had, for the most part, a minimum of six months training in the United Kingdom with the battalion. In many cases, it was ten months with the battalion, and in many it was four years.

There was a battle to win, and a battle to lose. How does an infantry battalion sustain itself in battle after massive, and repeated, losses? Capt Claude Bissell was part of the battalion’s tactical headquarters from August 1944 until the end of the war (see Lt Milt Boyd). It was a vibrant, vital ad hoc arrangement under Lt-Col Stewart and a shadow of itself under the inexperienced Lt-Col Fred Wigle. It offered Bissell a vantage point enjoyed by few others and no one was there longer. With a pre-war doctorate in English, Bissell was a percipient observer of the battalion pre- and post-Normandy. His perspective is worth considering. To his mind, one of the unit’s pre-eminent qualities is that it was “never shattered in battle.” I think immediately of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, brigaded with the Argylls from the start of the war. Its experience – at Tilly-La-Campagne in early August 1944 and then at Kapelsche Veer in late January 1945 – provides useful context. It was shattered in both. At the latter, the Argylls seconded (or whatever the military term is) RSM Peter Caithness McGinlay to the Lincs because of its difficulties in organizing supply for its rifle companies he received an MM for his efforts. The Argylls failed at Tilly, nothing more. Five days later, the story at Hill 195 provides an example of the most successful action undertaken by a Canadian unit in OP TOTALIZE.

Bissell pointed to the cadres of officers and NCOs who, in his mind, sustained the battalion through the turnovers wrought by casualties and the inexperience of reinforcements. It is worth noting that reinforcements joined the cadres of the experienced: Pte Colin MacLennan and ALSgt John Glavin provide compelling evidence of that fact. Lt Alan Earp, Pioneer Officer, considers Support Company (Carriers, Anti-Tank, Mortars, Pioneers) a “bubble” because it “and not least the Pioneers had sustained few casualties and had more than its share of old-timers and originals.

There is, in my view, another company bubble – Headquarters Company. Leadership matters, perhaps “most of all,” as Maj Maclean would have it. Administration matters too and the 1st Battalion had it from the beginning of the war till the end. Maj Bill Whiteside, MC, who had the Anti-Tank Platoon, then commanded Support Company and then D Company, was adamant on this point. The unit never looked elsewhere for assistance on this critical score; it was a given. The cadres of leadership at all rank levels in the rifle companies and the bubbles that were Support and Headquarters companies sustained what was left after the blood-letting of August to October. Maj Paterson told a story of C Company in the last weeks of October 1944. He decided to promote Pte John Wagner, an original Argyll, sergeant. Wagner declined the offer of additional stripes. “Then, you’ll be a sergeant without them,” Paterson replied. An incredulous Wagner asked, “Can the army do that?” Paterson’s laconic response was yes. Wagner retorted, “I hate the fuckin’ army.” Paterson smiled at the story’s conclusion. When asked whether Wagner did the job, the reply was positive, extolling John Wagner’s virtues as a good soldier and company leader, albeit with only one stripe (by choice).

The battlefields of France and the Low Countries were dangerous places. The reinforcements of September and October would join “old-timers and originals” in Bissell’s “shadowy company” of the dead. Pte Jack Reibeling had three weeks as an Argyll in a dangerous world far from the farm fields of Perth County, Ontario.

I offer my thanks to Pastor Sonja van de Hoef and Tricia Holmes Storey, Administrative Assistant, St. Paul’s United Church, Milverton, for their assistance and to Jennifer Georgiou, Archives Technician (Cataloguing and Digitalization), Stratford-Perth Archives, Stratford, for hers. In spite of their aid, I was unable to locate an image of Jack Reibeling. Once again, I offer my gratitude to “young” Lt Alan Earp for his thoughts on the battalion in which he served 76 years ago.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Jack Robert Reibeling (1920–44) (A 115951)

KIA 14 October 1944

Jack Reibeling’s great-grandfather was born in Germany in 1820. Jack’s grandfather, Henry Reibeling (1848–1921) was born in Waterloo. The northern townships of Perth County (Elma, Wallace, and Mornington) lay between the Huron Tract and Georgian Bay. An agriculture area, it was settled by the late 1840s by German, Scottish, English, and Irish immigrants. Andrew David Reibeling (1877–1963), Jack’s father, was born in Perth. Jack Robert Reibeling was born in Milverton, Perth County, on 19 May 1920, to Andrew Reibeling and Ida Catherine Eggert (1884–1964); they were married in Rostock, Perth Co., on 7 October 1902. Jack was the youngest of eight children; he had three brothers and five sisters.

Jack Reibeling was born on the family farm in Elma (lot 30, concession 16). In the 1921 census, Andrew Reibeling is listed as a Mennonite of German “racial origin.” He could read and write and spoke German, as did Ida Reibeling. He owned the farm and the family resided in a single brick house with “9/10” rooms. Andrew and Ida’s first child, Lincoln William Reibeling (1903–70), was born in Perth; his other language was German. Seven more of the Reibeling’s children are listed on the 1921 census; Lincoln was the only one with a language other than English.

“Worked on fathers [sic] farm at Milverton”

From his birth until 1944, the family farm in Elma Township was the horizon of his life and agriculture was the sum of his ambition. According to a local obituary, he “attended Lambert’s school after which he assisted his father on the farm up to his time of enlistment.” It accords with documents in his personnel file, which describe him a farmer who “Worked on fathers [sic] farm at Milverton, Perth County … since school.” He “completed 1st year High at age 14” and “Left school to help at home.” By 1942, young Jack had worked on the farm for seven years.

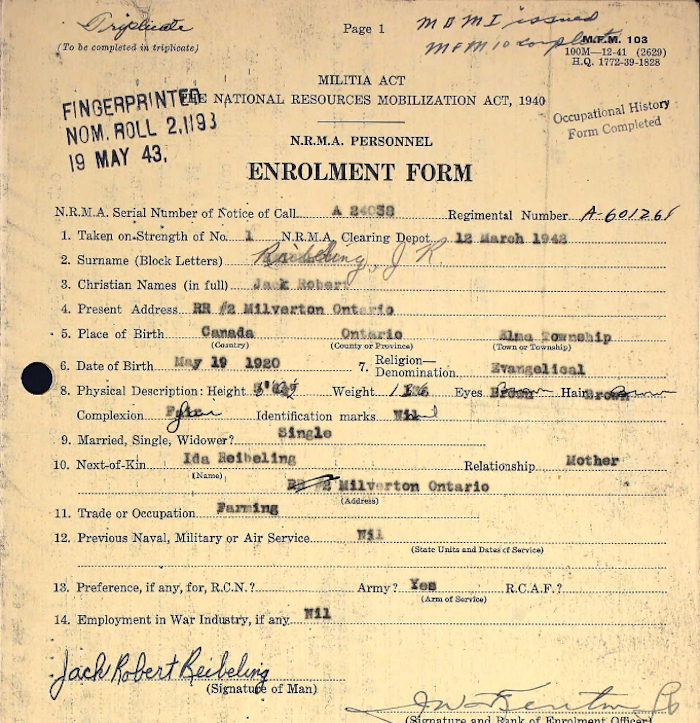

The issue of compulsory military conscription tore the fabric of Canadian society in the First World War. Prime Minister W.L.M. King and his Liberal government set out to avoid it in the Second World War. It was a difficult proposition with no easy means for resolution. The Canadian political dilemma of conscription resulted in the political compromise of the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) of 1940, a federal act calculated to reduce the clamour in parts of Canada for a more effective and all-encompassing war effort. The NRMA men were castigated as “Zombies” soldiers unwilling to fight overseas unless compelled to do so by statute or severe peer pressure. After a national plebiscite in 1942, the act was amended to allow the government to send home service conscripts overseas. The war in Europe and the Canadian response to it would change the horizon of Reibeling’s life.

“Cheerful but shy. Not aggressive. Average physique.”

Jack Reibeling enrolled at Kitchener, Ontario, on 12 March 1942 under the National Resources Mobilization Act; he was interviewed on 20 March. The examiner noted that he “Likes army. B.T. complete. Passed some T.O.E.T’s” and “Conduct sheet clear.” He spoke English, had a medical category of A1, and achieved a D grade on the “M” tests. Generally, he:

Likes sports, friendly, apparently makes good friends easily. Working at home on farm. Drives car. Appearance good. Only fair appearance, cheerful but shy. Not aggressive. Average physique. No preferences for any job in infantry yet. Drove cars, tractors. Very little repairing. Hobbies – carpentering [sic] raising chickens. Doesn’t like dancing. Likes card parties. Attended church young people[’]s society. Played softball. Can’t skate or swim. Single.

“Quite stable. Few interests except farm activities”

In summary, the officer found him:

Low learning ability. Gr. Education. Only fair appearance. Average physique. Pleasant. Quite stable. Few interests except farm activities. Only fairly sociable.

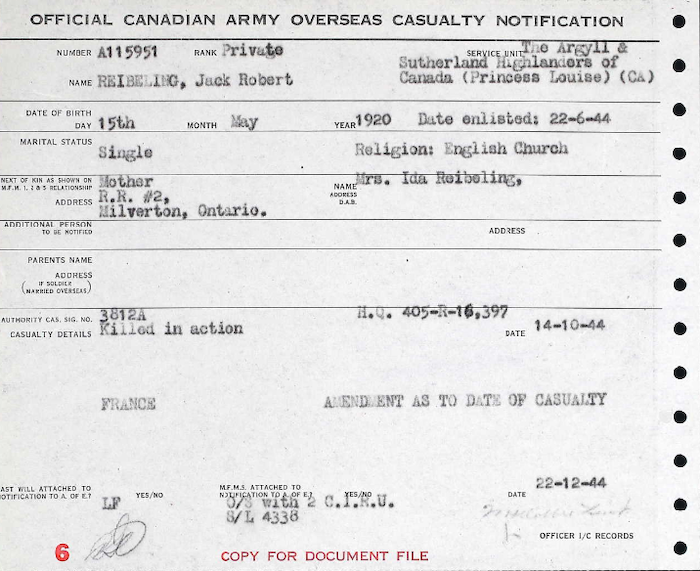

He preferred army service to the navy or air force and did 40 days of basic training at No. 10 Basic Training Centre in Kitchener, which he completed on 20 April 1942. He was 5’, 6½”, 136 lbs, with brown hair, green eyes and a fair complexion. He served in the NRMA from 12 March 1942 until 21 June 1944.

The political pressure to get more troops oversea did not abate. By July 1943, it was exacerbated from within the army but the lessons drawn from combat experience in Sicily. Army headquarters realized the high levels of casualties suffered by infantry. There was a need to steer new enlistments and those in training from army trades or other branches of army service to the infantry and the army acted upon it with: “H.Q.A.G. Secret Radiogram. (Org. 4061) Dated July 13, 1943.” Personnel Board Officers could now recommend different arms of the service and give priority to infantry over individual preferences or trade qualifications. By March 1943 pressure mounted on Reibeling for overseas service, pressure sufficient for him to seek legal means to postpone it.

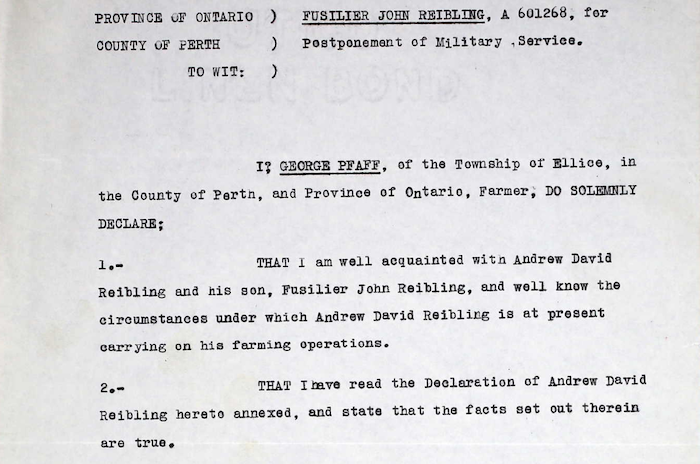

“Application of Fusilier John Reibling [sic]… for Postponement of Military Service”

According to his occupational history form of 26 March 1943, Reibeling left school at “15 yrs,” had “12 yrs” experience working as a “Farm-hand,” and was employed by Andrew Reibeling, his father. He felt competent to run a farm, his father promised to re-employ him after his discharge, and he wanted to “return to former employ.” A day earlier, George Pfaff, a farmer in Perth, submitted a legal document “in the matter of the Application of Fusilier John Reibling … for Postponement of Military Service.” Pfaff was “well acquainted with Andrew David Reibling and his son, Fusilier John Reibling, and well know the circumstances under which Andrew David Reibling is at present carrying on his farmer operations.” In a “follow up” interview on 21 September 1943 at Camp Sussex, New Brunswick, the officer pronounced Jack Reibeling “Suitable for operational duties (Infantry.)” Reibeling’s military record was spotless. Then, at Prince George, British Columbia, he went AWOL from 8 January to 11 January 1944, forfeiting “7 days pay in lieu of detention.”

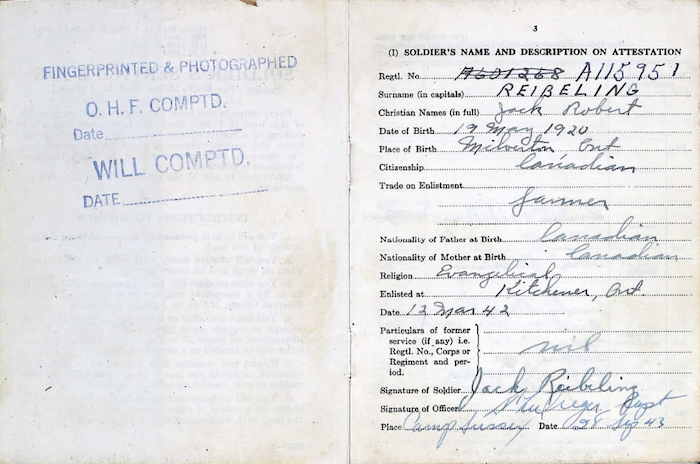

“Suitable for overseas service, C.I.C. – General Duty (N.T.)”

Reibeling enlisted in the Canadian army on 22 June 1944 at Nanaimo, British Columbia. At that time he had worked on his father’s farm for seven years. His medical examination on 16 June records that he now was 5’, 7” and weighed 150 lbs. His obituary noted that he “spent his embarkation leave at his home here [Elma] in June. He had “earaches when a child right” and a “1 scar on his left thumb.” He was interviewed at Nanaimo on 20 July “prior to despatch overseas.” The interviewer wrote this summary of Reibeling and his varied NRMA service within Canada:

Enrolled NRMA Mar 42. Basic trg at Kitchener. Adv trg at Camp Borden. Posted to Scots Fus – rifleman. Trans to PEIH[Prince Edward Island Highlanders] – employed as rifleman. No courses. No trade qualifications. MFM 6 – 1 entry. Enlisted GS Jun 44.

Short, husky solider who has recently enlisted GS. States his health is good and Pulhems profile indicates fitness for overseas service. Offers no problems and seems quite prepared to serve overseas. Rather quiet, unambitious soldier but seems fairly willing. Has made fairly good adjustment to army environment and seems stable. Non-tradesman.

Recommendation: Suitable for overseas service, C.I.C. – General Duty (N.T.)

“German descent. Speaks English only. Suitable Inf. Fld. G.D.”

The “Personnel Selection Examination of Documents Completed” stamp was added to Pte Reibeling’s forms dated 18 August 1944 and initialled “OK.” He left Canada for overseas on 28 August 1944, disembarked in the United Kingdom on 5 September, and reported for duty the following day at #2 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU). Pte Reibeling underwent yet another, albeit seemingly brief, interview at 2 CIRU on the 6th. There are no typewritten notes, only a few handwritten jottings. He was “Single,” of “German descent. Speaks English only. Suitable Inf. Fld. G.D. [Infantry Field General Duty].” With that recommendation, Reibeling was transferred to the X-4 list for unposted reinforcements, embarked for France on 16 September arriving there the next day. The Argylls took him on strength on 23 September 1944 at Sas van Gent, Belgium. It was “a day of rest, after a fairly strenuous two days.” According to one obituary, “the last word the family received from him was on October 5th, which conveyed the intelligence that he was in Belgium. Another brother, Gnr. [Gunner] Fred Reibeling, is also in Belgium but they had not met.” From the 14th to the 20th, seven Argylls were killed in action, including Capt Lloyd Johnston on 14 September, LSgt Jess Grey on the 18th, and Pte Paul Cole on the 19th; 16 were wounded. Johnston and Cole were both Scouts. The unit posted him to D Company. He was killed in action three weeks later. It was a relatively quiet period. Two Argylls were killed between 23 September and 13 October and ten wounded.

The first two weeks of October were given over to patrols and working, as D Company did at one point, with the South Alberta Regiment’s tanks. The weather had been “wet and cold” and the British had been unable to hold on to their bridgehead at Arnhem. A diversionary attack by the Argylls at Kerselaar resulted in a violent enemy response. Attempts by other units and the Argyll Scouts to cross the Isabella Canal failed. Most Argyll activity was confined to reconnaissance patrols.

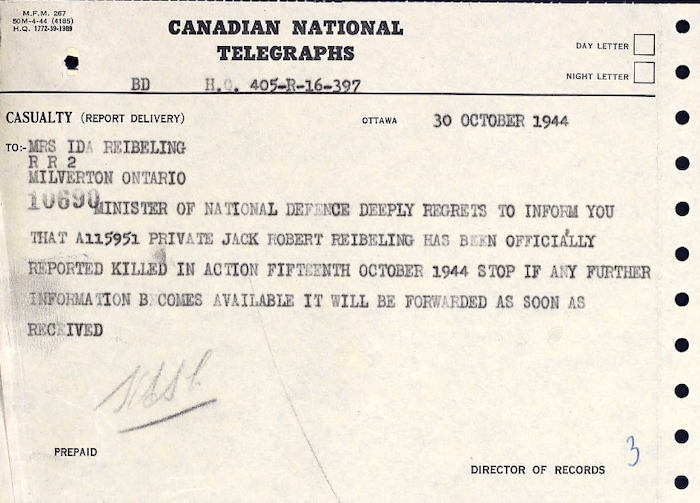

On 14 October 1944, the Argylls were in Kerselaar, Belgium. The unit war diarist, Lt Claude Bissell reported that:

The morning dawned clear and bright. On the basis of the last two days’ reports and the facts of the tactical situation, the C.O. decided that the time was ripe for an Argyll crossing of the canal. He therefore ordered the Pioneers, with the protection of the Scout Platoon, to clear the main road of fallen trees up to the canal, and to find some means of crossing the obstacle. At 1220 … the astonishing report came back that the Scouts and the Pioneers were in Watervliet! They had cleared the road … had improvised a foot-bridge … and had then proceeded to Watervliet, a distance of approximately 1000 yards, clearing the road of mines as they went. They found only a few bewildered enemy, who were promptly taken prisoner. The C.O. then ordered “A”-Company to cross … and “C” … to pass through and to clear the houses on the road leading northward from the town. In the meantime the pioneers returned to this side … to assist the Engineers in constructing a ferry bridge at a point about 600 yards to the east of the original crossing. The fact that the enemy was still occupying slit-trenches … had dampened the Engineers’ enthusiasm for their task. During the afternoon and evening, the whole operation proceeded smoothly …

By 2200 hours “C” … had advanced northward from Watervliet about 1000 yards before contacting the enemy, who was dug in along a dike and offered fierce opposition to any further advances. At the same time, they were being subjected to heavy shelling, from which they suffered about 9 casualties…

“a bitter action”

Pte Reibeling was the only Argyll killed on the 14th. According to Part 1 orders, he was posted to D Company when he was taken on strength. There is no account of D’s activities that day. The phrase, “the fog of war” is apt for battlefields generally and not simply the large realm of chaos faced by commanders.

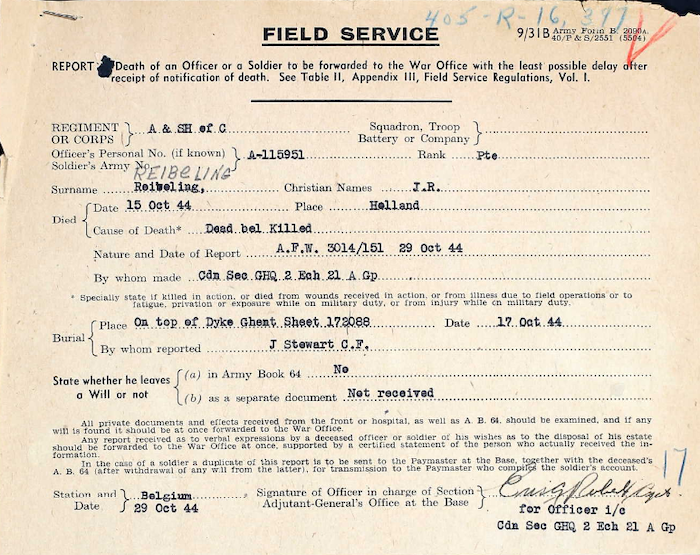

Pte Reibeling’s personnel file contains two death dates: 14 and 15 October; one form has both dates on the same page. Another form – his Grave Registration Card — has 15 crossed out and 14 written over it. His official death certificate has the 14th. His entry in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial has the 15th. It remains unclear. There is, however, one Argyll account of a nameless Argyll killed in action on the night of the 14th, which suggests it was one of the Scout Platoon. The writer belonged to C Company and no one from C died on the 14th. The next day, Ptes Muir Marlatt, Gordon Marr, and Alexander Nickoloff, all of C, were killed. Pte Bill Patrick was wounded at 2200 hours on the 15th and died the next day.

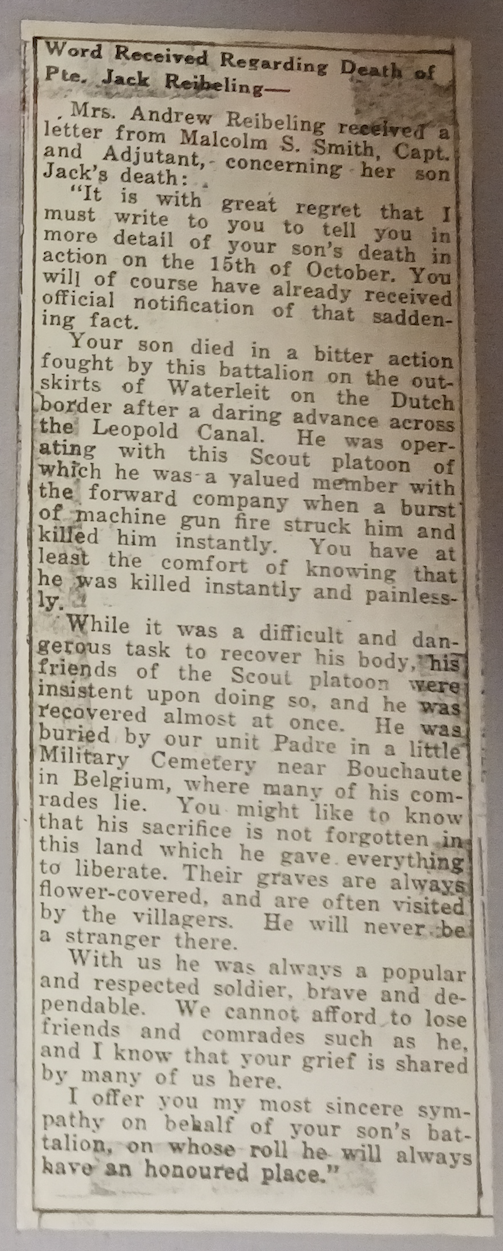

Capt Mac Smith, the Argylls’ adjutant, wrote a letter to Ida Reibeling “with more detail of iyour son’s death in action on the 15th of October.”

Your son died in a bitter action fought by the battalion on the outskirts of Water[v]liet on the Dutch border after a daring advance across the Leopold Canal. He was operating with this Scout Platoon of which he was a valued member with the forward company when a burst of machine gun fire struck him and killed him instantly. You have at least the comfort of knowing that he was killed instantly and painlessly.

“crying outside there: ‘Come and help me’ … That poor guy died out there that night”

In an interview, Pte Art Bridge, C Company, talked about the night and separated it from what happened on the 15th:

…There were a whole series of incidents that got to me. In the night, we were in a small shed under fire and one of the scouts who had been with us, or gone ahead of us, he was outside the little house that we were in and the Germans kept coming and attacking and throwing grenades at us. And this poor guy – the scout – got hit. And I don’t know what his name is, or was [it was Pte Jack R. Reibeling], but I can hear him now crying outside there: “Come and help me.” And we didn’t go and help him and I’ve never forgiven myself for that. That poor guy died out there that night.

“a popular and respected soldier, brave and dependable”

After his initial posting to D Company, Pte Reibeling became a Scout, possibly in September as a replacement for Pte Cole; there is no indication in the unit’s war diary appendices for October of his transfer from D to the Scouts. Yet the adjutant, who would know, is definite on this point. Mac Smith’s letter to Ida Reibeling is one of consolation and compassion; no parent would have wanted to know Pte Bridge’s agonizing account of Reibeling’s death. In the circumstances, even the recovery of his body proved hazardous, as Smith recounts:

While it was a difficult and dangerous task to recover his body, his friends of the Scout platoon were insistent upon doing so, and he was recovered almost at once.

Padre Charlie Maclean buried him on the 17th “On top of dyke GHENT.” There was the customary service, brief and reverent, with a Regimental piper playing the Argylls’ lament, “Flowers of the Forest.” In his letter to Ida Reibeling, Smith wrote:

He was buried by our unit Padre [HCapt Charlie Maclean] in a little Military Cemetery near Bouchaute in Belgium, where many of his comrades lie. You might like to know that his sacrifice is not forgotten in this land, which he gave everything to liberate. Their graves are always flower-covered, and are often visited by the villagers. He will never be a stranger here.

With us he was always a popular and respected soldier, brave and dependable. We cannot afford to lose friends and comrades such as he and I know that your grief is shared by many of us here.

I offer you my most sincere sympathy on behalf of your son’s battalion, on whose roll he will always have an honoured place.

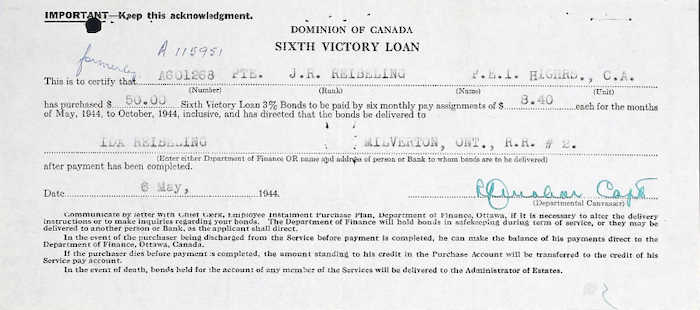

Reibeling left everything to his mother. After his death, she wrote the director of estates “in regards to bonds purchased by. Pte J.R. Reibling I have 2 here. The last one he bought was May 6 1944 … will you kindly see about it and his personal belongings I would very much like to have them if at all posible [sic]mand about his Will he said he made one and was leaving all his belongings to me his Mother but it must be with his belongings hope every thing is satisfactory.”

“the sacrifice that this young man has made for the cause of freedom”

On 5 November 1944, St Mark’s Evangelical United Brethren Church, the family’s church in Milverton, held a memorial for “Private Jack Reibeling … killed in action overseas on October 15th.” The church was filled to capacity by “the people who came from town and community to pay their last tribute to this gallant lad who had give up all to serve his country.” The church was adorned with “seven beautiful baskets of mums” presented by “loved ones, friends, patriotic chapters and St. Mark’s Sunday School.” The reeve expressed “words of sympathy to the family and paid tribute to the sacrifice that this young man has made for the cause of freedom.” The Reverend F.M. Faist spoke of society’s “debt to these young men who stand between us and destruction…. they did not want war … it was from a sense of duty that these young fellows answered the call of King and Country.” “Democracy,” he exhorted the mourners, “must live in us or else these gifts of life shall have been in vain.” Jack Reibeling’s name is on St Mark’s Roll of Honour; the plaque is now mounted in St Paul’s United Church, Milverton (the congregations merged in 1968).

Within the space of 100 years, the Reibeling family emigrated from Europe to the British colony of Upper Canada. Four generations farmed in Perth County and Jack Reibeling hoped to continue that tradition. The Second World War and Canadian participation changed all that and took a “pleasant” Perth County farm lad back to Europe and to his death. There were no choirs, no baskets of flowers, no throng of family and community, no reverent testimonials to high ideals of service and sacrifice on top of a dyke on the Ghent canal when a padre, a small burial group of Argylls and one lone piper laid Pte Reibeling in his temporary grave – a “stable” lad with “Few interests except farm activities.”

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Reibeling’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Pte Jack Reibeling

Bren gun instruction, Camp Sussex, New Brunswick, 1943.

Soldiers on parade, Camp Sussex, New Brunswick, 1939–45.

St. Mark’s Church, Milverton, Ontario (photographed about 2010).

Honour roll at St. Mark’s Church, Milverton.

Gravestone of Andrew Reibling and Ida Eggert, Milverton, Ontario.