Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

NOTE ON REVISED TEXT: MORE INFORMATION ON THE DEATH OF PTE COLE

Over the past few months, I have paid more attention to the Scout Platoon. There are four reasons: first, the celebration of Scout Tony Mastromatteo’s 101st birthday; secondly, I have corresponded with Murray Cooper, the son of Scout Fred G. Cooper (1924–2010), and the nephew of his father’s best friend, Scout Jim Crawford; thirdly, I received new information about Pte Jack Robert Reibeling, which confirms that he was a Scout; fourthly, through the good offices of the CO, LCol Carlo Tittarelli, I have been in touch with the family of another Scout, LCpl Lloyd David Joseph Martin (KIA 11 March 1945).

Murray Cooper has delved into his father’s wartime service and read everything related to the Argylls, including the so-called “Green Book.” Its wartime chapters were written by Maj Hugh Maclean in the summer of 1945. There is a picture of “Junior” Crawford between pages 214 and 215. He looks nothing like Scout Jim Crawford. Murray wondered if there were two Crawfords in the Scouts.

I checked the now-digitized copies of the Albainn, the 1st Battalion Veterans’ newsletter. In volume 9, no. 8 (October 1971), Gord Berkhold wrote about “Junior” Crawford:

JUST GATHERING UP some old papers to throw out, & I came across “Dempsey Crawford’s” picture, good old transport, so I just had to send it along. Clarence Crawford now operates his own “Dempsey’s Diner” on Morrison Street, St Catherines. (The picture reveals a full head of dark hair. Remember he was known as Junior!!)

Pte Clarence “Junior” Crawford was in the Transport Platoon, not the Scouts. When Scout Jim Doyle recollected the patrol on which Pte Cole was killed, he misidentified Jim Crawford (a reinforcement who joined the Argylls in the United Kingdom) as “Junior,” an original Argyll, like Doyle, who enlisted in 1940.

I am grateful to Murray Cooper for bringing this matter to my attention.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

30 December 2022

Introduction

As with so many other Argylls killed in action, I learned their names from surviving veterans who never forgot them. Such is the case with Pte Paul Cole of the Scout Platoon. Cpl Gord Boulton, Scout Platoon, talked reverently about his platoon commander, Capt Lloyd Johnston. Gord could barely speak when mentioning “Cosy” Cole. It mattered to Gord that their lives be remembered and that living family knew how their wartime comrades felt about them.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Liberation of Sas van Gent

19 September 1944

War Diary. 19 September 1944. Sas van Gent, Holland [C.T.B.]

At an “O”-Group, held at 0730 hours, the C.O. announced that it was his intention to take Saas Van Ghent [Sas van Gent], a fairly large town just inside the Dutch border, on the Neuzen canal.

The method was as follows: “B” Company plus a troup [sic] of tanks was to move up and take Staak, a small town, really a suburb of Saas Van Ghent [sic], directly to the west. “D” … was to move up along the road beside the canal and enter the town from the south. It was expected that the enemy would provide the same kind of opposition as they had in the previous days’ operation, and this proved to be true.

“B” … set out at 0830 … and at 0915 … reported themselves held up by [a] roadblock, consisting of trees felled across the road, which was covered by fire. A large factory on “B”-Coy’s flank near the canal was the obvious centre of enemy activity. “D” … was ordered to send a patrol…. Within an hour the patrol had sent back some 21 prisoners, including a complete mortar crew. Around 1230 … the C.P. moved to … a road junction with a good view of the factory, and within a short distance of all the companies. By 1715 … after some hard fighting, during which the S.A.R.’s lost a tank from 88’s, “B” Coy reached its objective.

“D” and “C” … had left at 1330 … “C” was forced to advance through the factories on the left … since the road had been rendered impassable, and for a time lost contact with the tanks. By 1900 … both Companies had moved into Saas Van Ghent, and had taken up positions, after clearing out slight enemy opposition…. Further international flavour was given to our activities … by the attachment to “C”-Company of some 7 or 8 men from the Belgian White Brigade, who insisted upon sharing the ardours of battle with the bona fide soldiers. Major Patterson [Paterson] reported that his undocumented reinforcements were particularly valuable as escorts for P.O.W.’s, a role that they played with understandable enthusiasm. About 60 prisoners were taken during the day.

[KIA: L/Cpl James E. Joselin, Pte Paul J. Cole and Pte Eldon D. Morton. Wounded: 6.]

Private Diary. Cpl Harry Ruch. 7 Platoon, A Coy

We now have Jerry pushed over and hemmed in between the Leopold Canal and the Scheldt outside of a few pockets. To-day we set out for a place called

Assende [Assenede] just near the Dutch Border. We moved up and with isolated opposition our Unit managed to capture our first Holland town called Sas Van Ghent with few casualties although there was quite a tank battle there; Jerry losing 5 Tigers, we lost 3 [in fact, one] Shermans. We took position outside of the town to stay for the night.

Interview. Sgt Tommy Dewell. D Coy

I killed another one there at Sas-van-Gent, and I took forty-some prisoners. I shot that bastard there. He couldn’t hit me, son-of-a-bitch. The bullet whistled right by my ear. Geez, I got him though. That’s the only one I killed up there.

Sas-van-Gent was not a very big place…. Happened to be a very foggy morning. They couldn’t see you coming. And the sergeant in the tank, he wanted to bring the tank in. I said, “No, you don’t bring your tank in. You’re going to make too goddamn much noise. I won’t need you anyway.” … Everyone’d go along and see little white flags come out around you. Bring them down, five or six of them [prisoners]. I said to one of the guys, “Take them out to the road and call them there. Go and see what the hell else is in there.” Went a little farther, few more of them flags, and take them out.

Reminiscence. Capt Bill Duncan. OC, Support Coy

As Coy Comd of SP Coy, I was usually moving in advance of the Regt. main body or just behind them. On the 18 + 19 September 1944 the Argylls advanced from a

small group of houses at Staek [Staak] in Belgium. The Germans offered heavy opposition to the Regiment and the South Albertas from a factory area near the canal which had to be crossed to enter Holland.

It was in that factory area that we liberated 2 huge railway guns. We took about 30 POW’s from the area. And then proceeded to cross the canal and entered

Holland. It is recorded somewhere that the Argylls were the first Canadians (or British) to enter Holland.

As SP Coy Comd, I was given the task of advancing into the first town Sas Van Ghent and arrange for “digs” for [Lt-Col] David Stewart and HQ of the Battalion.

As the tanks and “C” and “D” Coys moved into the town I drove my jeep up a street that entered the market square. It was vacant of people as I braked to a

halt. Then all hell broke loose: people flooded into the square from houses, bomb shelters and wherever they had been hiding and mobbed my jeep. Just to add to the excitement, a sniper fired from somewhere and the bullet hit the hood of the jeep + ricocheted without hurting me or anyone else.

A man approached me, I think he was a member of the underground, and asked if it would be safe to put up their flags and when I asked him, why not, he said that the Germans may return. My answer was to the effect that the Argylls would make certain that that would not happen. With that this fellow signalled to

someone, a great roar went up and, like magic, orange flags popped up everywhere. It was a very touching sight. When I asked for accommodation for the Colonel, they took me to a huge home and opened it for us to use. It was the most wonderful day of my life except my wedding day … 19 Sept 44 my 4th wedding anniversary.

The excitement of that day and weekend made us hope that the war was over. I took one of my carriers and drove up to the Scheldt Estuary to see what it was we were trying to liberate. Around that time, the Lincoln & Welland sank a small boat full of Germans with their 6 pounder A/TK guns. So the story goes.

Our bubble was pricked when on returning to Sas Van Ghent we had orders to return to attempt to remove 50,000 Germans at Breskens. That is another story.

Interview. Lt Fred Hammond. D Coy

I remember going into Sas-van-Gent … and I recall Lieutenant Poppleton led his platoon down the left side of the road and I led mine down the right-hand side and I remember Bill Whiteside saying we must have been the first Canadians into Holland.

Interview. Cpl Tommy Dewell. D Coy

I don’t think there were any Canadians in Holland when we got in there. There was no Germans there. They were all gone. Then I had a drink up there. Yeah, I had a drink up there. This … Dutch tavern, old guy that owned it. Oh, he was happy as hell. He had a couple of sons that were forced into labour under the Germans. He went down in the cellar and brought up a couple of bottles of gin. Oh Jesus, it was good stuff, too. “Yeah,” I said, “Okay, yeah, we’re here for a couple of days.” So we drank a couple of bottles of gin…. Then he made us beds up for the night … made us breakfast in the morning. Good old guy. He was happier than hell. Oh, they all were, to get rid of them goddamn Germans. Geez, that’s why the people in Holland … like Canadians so much.

A/Major D.J. (Pete) McCordic to his brother. 12 December 1944. C Coy

[This letter was written shortly after McCordic was given command of C Coy.] Needless to say we have our good days and our bad days but so far the good

outnumber the bad….

As acting O.C. of “D” Coy. my objective was a large town inside the Dutch border. We had under command one troop of tanks and field arty, 3” mortar and 4.2

mortar on call. I didn’t have a F.O.O. with me. My information was that there were two German companies in the town. We were to pass through “B” Coy. after they had taken their objective, a cross road on the outskirts of town. “B” Coy. ran into road blocks and some small arms fire and were a couple of hours late getting on their objective. The carrier platoon protecting our left flank ran into a fair amount of trouble. We moved to “B” Coy.’s position with only about an hour of daylight to go and we were to be on our objective by dark. There was no time to clear houses or soften the place with Arty.

I lined up the company as follows – two platoons of infantry leading one on each side of the street, four tanks followed by my reserve platoon. Coy. H.Q. moved beside the command tank which was the lead tank that day. I left my carrier and jeep in “B” Coy. area, the signaller carrying the 18 set. The 19 set is installed in the carrier and served as a link to control. The jeep is equipped with stretcher racks and stretchers and can be called up in case of casualties. We moved right down the main street towards the main square, a distance of about two miles. To let them know we meant business the lead tank fired two 75’s, one into the windmill and the other into the church tower. No more shots were fired and we moved in and circled the town square. The priest’s [sic] covered the four streets approaching the square and the three platoons deployed tactically with considerable regard being given to decent living quarters. Later that evening we rounded up about 50 prisoners but only found the officer’s hat. We stayed over 24 hours and as the civilians were quite happy to be liberated the boys had a good time. From there we went feuding again.

That was a good day.

Interview. Lt Ed Brook. Carrier Platoon

Pete McCordic and I … were the first people to cross into Holland at Sas-van- Gent … and there was a corn syrup factory, and we met the local manager…. And he said Jerry had moved out, but they [the Germans] had issued them their coal rations to make syrup about four or five weeks before…. So for a few treats we had in our packs – sweets and bully beef and things of that nature – we got a four-gallon can of corn syrup. I remember giving the Colonel a quart and a few others, and we had corn syrup on everything.

Capt Sam Chapman to his wife. 19 September 1944. C Coy

Everything is under control – when there is work to be done the danger does not seem to bother me quite so much. And I am almost getting blood thirsty.

Yesterday a sniper pegged at us for half an hour before we finally got him routed out and then he threw up his arms. It wouldn’t have bothered me in the least if somebody had let him have it.

There is a thrill in entering a town as first troops that a fellow could never forget. People crowd about and shout + grab hands and try to kiss troops, throw flowers apples pears, wave flags, carry beer + cognac. And all this even before the last Jerry is swept up. Yesterday we had to shoot down a street (overhead of course) to get them to clear off a little.

In the very beginning they are a little afraid and do all the stupid things you’d expect – such as locking up the doors, and when we want in for a reason we

naturally go, no matter what they think about it.

Quite a few here speak a little English. This place this morning looks + acts like Toronto on the 12th of July. The people seem to think “Tipperary” is our national anthem.

Private Diary. Cpl Harry Ruch. 7 Platoon, A Coy

[Ruch wrote this note and added it to his diary while in hospital in late October or early November.]

The Dutch had suffered under the Germans but didn’t show it as much as the others. They are a solid and clean race and while we could see they were glad to

see us they were not as demonstrative and did not show their feelings like the others. They were more united than the rest and hated the Germans quietly, but bitterly. Their resistance force took their place immediately thus saving us troops. The Dutch are a race to be admired but hard for us to understand or get close to because of their silence. They have suffered but keep a solid front and hide it from the world. A truly great race of people.

Interview. A/Major Jack Harper. OC, A Coy

… we went through this town. We’d picked up a fair number of prisoners. And a guy came walking down the street, all dressed up in a pretty gaudy uniform which obviously was a dress uniform for local constabulary – that’s my assumption. So he’s walking down towards me and his hands are up in the air. And so when he gets to me, I talk to him and he speaks English. And he said, “I was the chief of police of this town and,” he said, “I was tortured. I have been hiding and,” he said, “I’m surrendering and I’m offering you my help.” He said, “If you don’t believe me, let me show you.” So he took his pants down and raised his shirt, and you could see scars all around his groin and all that kind of stuff, where he’d been burned…. Then I guess you said, “Well, those buggers…. That’s the kind of human being they are” – and you would get regenerated. You’d get mad again and you’d want to get going.

Part I Bn Orders. 19 November 1944

1. H1390 Pte Galloway, CA, A & S H of C was tried by FGCM on 19 Sept 44 on a charge relating to wilfully injuring himself (SIW). The accused pleaded guilty, was found guilty by the court who sentenced him to be imprisoned with hard labour for 3 years and to be discharged with ignominy from H M Service.

2. The finding and sentence having been confirmed by the CIC Cdn Sec GHQ 1 Ech A1 A Gp were promulgated on 22 Sept 44.

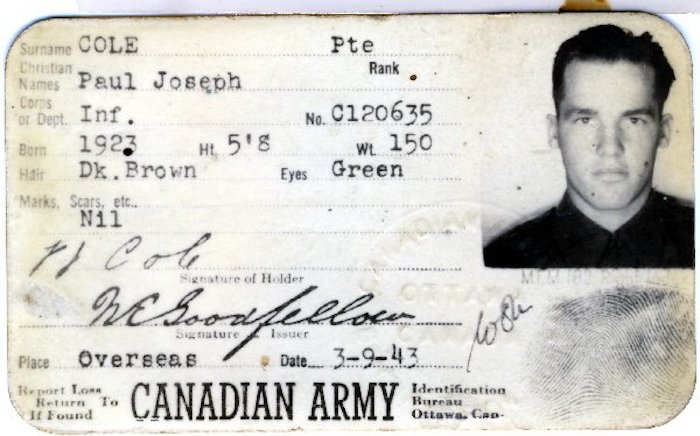

Pte Paul Joachim (Joseph) Cole (1925–44) (C120635)

KIA 19 September 1944

Over 40 years after the end of the war, veteran Capt Sam Chapman reflected on the experience of the 1st Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada. His ruminations frame each biography of an Argyll killed in action.

“the man who falls in battle is far from his family”

“Death in battle is different,” he wrote:

… from the inevitable end which every man ultimately reaches. Normally, a man dies in the bosom of his family, at peace with his God, and after receiving the best possible medical care. He is mourned by his friends who take solace in the knowledge that he had his innings; he had his chance to make his mark in business or the academic world, to inspire others by his knowledge and example, to see his children grow and take their place in society. Death is the natural end to a cycle of life. In contrast, the man who falls in battle is far from his family; circumstances dictate that his medical care is less than ideal; his comrades may be there but are so involved with the task in hand that they can give him scant attention. He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank. There is an end but no conclusion.

The younger the Argyll killed in action, the truer Sam Chapman’s characterization of death in battle, and Pte Paul Cole was young.

“Board + allowance monthly”

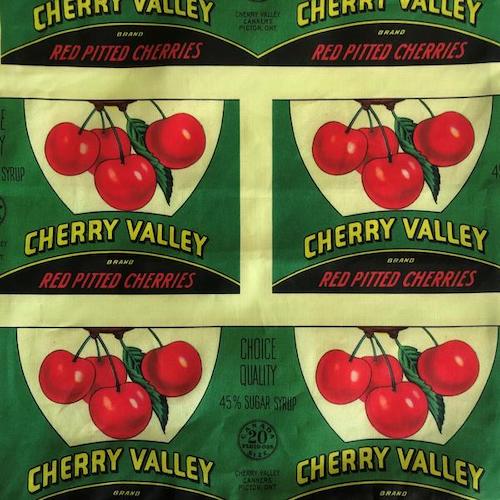

Paul Cole was born on 16 August 1925, the youngest son of a large farming family, in Prince Edward County, Ontario. His parents, James Harvey Cole (1884–1942) and Helena Aloysia Harrington (1882–1971) were from Prince Edward County – “The County” as it was, and is, known. Paul signed his name Paul Joseph Cole; he was baptized Paul Joachim Cole. His early education presented challenges. He attended a rural school and because of “distance from school” and, no doubt, the Depression, he had “Irregular attendance.” The school was three miles away and Paul “worked at [the] farm.” As a result, he had “failed several times.” He had completed grade 5 and “partial” grade 6 at age of 15. Prior to enlistment he had worked from 1938 to 1942 on his father’s farm “+ others” for “Board + allowance monthly”; six months in 1942 at Cherry Valley Canners making $18 monthly, and three months in 1942 as a “rod man” at the Royal Canadian Air Force base in Trenton earning $24 weekly.

“Joined with friends”

Paul Cole enlisted at Kingston on 2 March 1943; he was 5’, 7 1/2”, 149 lbs, with blue eyes and brown hair. He later explained his reason for enlisting: “Joined with friends.” The Personnel Selection Board (PSB) officer noted that:

Mother lives in Picton. Father is dead. Has seven brothers and two sisters. One brother is in the army, one a farmer, one a butcher. The others are at home. One sister is married; the other at home. Says health is good – no complaints.

Young Cole played softball and liked hunting, riding, and swimming. He had: “Normal social interests. Reads pulp magazines. Smokes very little. Does not drink.” As for the post-war, he hoped “to return to farming … one of his own.” After training, the PSB officer “considered [him] suitable for overseas reinforcement.”

“should succeed as general duty soldier”

On 13 March 1943, Pte Cole was posted to No. 31 Canadian Basic Training Centre at Cornwall, Ontario. After completing basic training, he was transferred on 20 May to A-11 Canadian Infantry Training Centre at Camp Borden for advanced training. He received a 14-day furlough on 12 July and, presumably, returned to his family in Prince Edward Country. He was struck off strength at A-11 on 23 August to #4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU) and proceeded overseas two days later. He disembarked in England on 1 September. He was interviewed at #4 CIRU two days later. The PSB officer found him “Quiet – responsive” and of “Good” appearance adding:

Narrow range of interests reflecting restricted experience. Seems normally stable and although well below average intelligence should succeed as general duty soldier.

PSB officers routinely made such comments about soldiers with limited education, disrupted education (usually because of distance from schools and the exigencies imposed by the depression, and the lack of familiarity with tests for literacy and numeracy. In such cases, they often relied upon appearance, deportment, manner, character, and verbal skills to take the measure of a man. He was granted the regimental rate of pay – $1.50 daily – on 2 September. Trained as a rifleman, Cole hoped to be a driver mechanic.

Pte Cole was taken on strength with the Argylls on 2 October 1943 as a rifleman along with Ptes Ira Hedman and Johnny Sawyer. Cole had no crime sheet, not a single minor blemish on his record. The daily jottings of the battalion’s war diarist, Lt Milt Boyd provide a glimpse of company and battalion life. For the most part, a rifleman lived that life at the section and platoon level. Cpl Bill Hollinsworth’s letters provide some sense of the reaction of soldiers to the various moves, the field training, and the adjustment to English weather.

“the newly organized specialist or scout platoon. Comprised of picked men”

On 8 March 1944, Lt Boyd wrote in the unit’s war diary:

A source of much interest of late is the newly organized specialist or scout platoon. Comprised of picked men from the different companies … they should prove a valuable addition to the unit. The men will be thoroughly trained in the arts of fieldcraft; have a comprehensive knowledge of enemy weapons and in some instances be bi-lingual.

“They’re going to pick thirty guys”

Lt Lloyd Johnston, the newly appointed Scout officer, interviewed interested Argylls “in the whole unit.” He picked Pte Paul Cole as one of “thirty guys” for the new platoon. Cpl Gord Boulton recalled:

…they said that they were getting a scout platoon together … and they’re… interviewing for it in the whole unit … They’re going to pick thirty guys … and I was tired of being a private, too…

…I thought, “Dammit, I’m gonna go for that,” you know. So I put in for it and I was interviewed by the officer, [Lt] Lloyd Johnston, who was an unbelievable person, fantastic individual. And he asked me why I wanted to be in the Scout Platoon, and I told him … “Well, for one thing, I’m tired of being a private,” and I said, “You’re going to make three corporals and I’m going to be one, you know.” So he said, “Well, we’ll see about that.” He said, “Do you really want to come with us?” I said yes…

“when you’re a scout … You’re on your own”

The irascible Pte Jim Doyle liked the structure or, to him, the seeming lack of it:

… when you’re a scout, you don’t have no officer to contend with. You’re on your own. And if you get in trouble, you get out yourself … That’s why I was a scout, because I remember, I got no asshole of an officer getting me in trouble…

“the only platoon … that came directly under the CO”

There was, of course, a command structure and the Scout Officer, especially one such as Capt Lloyd Johnston was certainly an integral part of it. That said, it was a looser structure. Maj R.D. “Pete” Mackenzie commanded Support Company:

They [the scouts] were the only platoon organization that came directly under the CO. They were nominally under my command in France, but the jobs they were given either came directly from the CO, or from the CO to me to them.

If you’re not afraid, then you’re not wary. But we were …

Pte Cole disembarked in France with the Scouts on 22 July 1944. Lt-Col Dave Stewart trusted Johnston and used the Scouts frequently. Cpl Boulton explained:

… you don’t really know what to expect and you’re still scared. I mean anybody who says they’re not afraid … doesn’t have a brain, you know. You gotta be afraid, or else you wouldn’t be affected. If you’re not afraid, then you’re not wary. But we were …

The Scouts experienced the sights, smells, and sounds of battle as did the rest of the battalion reacting to the early casualties such as Pte Percy Hindle, Pte James Bannatyne, ACpl Coningsby Gooderham, Pte Bill Wingate, LSgt Tommy Page, LCpl Jamie MacRae and others. The platoon quickly achieved battalion-level renown especially after its exploits at Hill 195 on 9-10 August 1944. At Hill 195, the Argylls excelled in the imaginative, unorthodox, daring and disobedient leadership of Lt-Col Stewart; the prowess and training of the Scout Platoon; the leadership of officers and NCOs at the company and platoon levels; and the “warrior spirit” of well-trained soldiers confident in their leaders.

“I took the scout platoon with me and we reconnoitred the route I had chosen”

On 9 August a combined force of British Columbia Regiment (BCR) tanks and Algonquin Regiment infantry attacked Hill 195 – “an obvious strongpoint … the highest ground between Caen and Falaise.” The battle group got “off track” and was decimated by the Germans by late afternoon of the 10th. The BCRs lost 47 tanks, 112 men killed and wounded, and 34 POWs; the Algonquins lost 128 killed and wounded and 45 POWs. Stewart received to attack about 2200 hours on the 10th:

When we received the orders to take “Hill 195” it was late … and two other regiments had tried but were misdirected and got off the track. I mentally wrote the Argylls off as well as myself.

I took the scout platoon with me and we reconnoitred the route I had chosen. On the way back I left members of the scout platoon at strategic points, to guide the Battalion, so I could lead them up to the high ground.

Stewart’s verve on the night made a lasting impression on Capt Bill Whiteside of the Anti-Tank Platoon:

…the CO came back and we had an O Group. And it was at night, and he said, “This is what is happening and the first company moves … in twenty minutes…”

“… the regiment’s style was Stewart’s style …”

In his post-war ruminations, Maj Hugh Maclean thought:

… the regiment’s style was Stewart’s style … there was a battle to win, or lose, and a certain style to maintain. A manner, if you like, with which to confront the inscrutable face of battle, and endure in spite of it.

“a night movement with Scout Platoon providing pickets”

That style was on stunning display in Stewart’s late-night O group. In his own mind, from the time of the order, he wrote off his battalion. He said once, a “CO to my mind is the most lonesome occupation that could be…. Get a job done; save lives.” That night, he did both and in magnificent fashion. Capt Pete MacKenzie, OC, Support Company was in the O group:

Dave Stewart was very positive about it. He certainly knew the problems, but he had a very definite plan of a night movement with Scout Platoon providing pickets to make sure nobody lost direction. He was confident and I think all the company commanders left his O Group with a feeling of confidence that it could be accomplished.

“Piece of cake. Piece of cake. We’ll take it. We’ll take it.”

The O group was a master class in the dissimulation that, at times, is essential to inspired leadership in dire circumstances. Stewart inspired confidence in all his audience save one. He never forgot it:

There was only one doubt in anybody’s mind, and that was Stockloser. That’s the first time I saw [Major] Stockloser [OC, D Coy] in his right light. He let me down. And [Major] Pappy Coons [OC, B Coy] said, “Piece of cake. Piece of cake. We’ll take it. We’ll take it.” He [Coons] went up in my estimation terrifically from there on … [Stockloser said,] “You’re sending us to our death” … I ignored it.

“single file to the high ground”

As Stewart explained: “I had to improvise … I never went by the book … it is the Tory personality.”

I took them in single file to the high ground and luckily it was “Hill 195” and we went right through the German lines. When we reached the top, I advised the company Commanders to dig in and I distributed the [Battalion] about the hill. When it came light in the morning, the German reacted very strongly and shelled our positions.

The war diarist recorded:

The Argylls’ attack on Hill 195 took the following form: A circuitous route to the East and North-East of the feature was chosen, as the area to the West was known to be defended heavily by the enemy. The C.O. sketched the route to the Scout Platoon and they went out in advance to piquet the advance of the Battalion. The advance began at 0001 hours, at 0430 hours the leading elements were within a few hundred yds. of the objective, without as yet having encountered any enemy. There the C.O. pointed out to the Company Commanders their respective positions – positions that previously [had] been picked from the map – and the marching troops were despatched to them forthwith with the instructions to search the area for enemy and “dig like hell.”

Pte Jed Simmons, Mortar Platoon, had just finished digging a slit trench – “I dug, and dug, and dug” – and was “soaking with sweat”:

… And just got that done … and [Lt Al] Rathbone come up and said … “I’ve just come back from an O Group and this is the picture. Now, we’re gonna go through the German lines … we’re going up to 195. It’s too sticky, we’ll never get to our objective the way we’re doing it, so we feel if we go through after dark, we can sit right on the thing and let them come to us…”

“moved onto the top of the ridge, still without opposition”

Lt Ken Frid, commanded a platoon in D Company:

… that night we received orders to push on to Hill 195. D Company was vanguard and mine was the leading platoon. I wasn’t too happy about it because it dominated all the surrounding country and I didn’t think “Jerry” would care to give it up as easily as the Intelligence reports intimated. Well, we moved off about 2 a.m., using a circuitous route, and arrived on the objective about two hours later and moved onto the top of the ridge, still without opposition, and very joyfully began to dig in…

“told we’d be walking through the enemy line”

According to Pte Bob Post, D Company:

…We were told to be damn quiet and to follow up this rope or a string they had lined up … I believe we were told we’d be walking through the enemy lines…

“the whole unit was coming single file”

For Cpl Boulton of the Scouts, the companies were somewhat less than “damn quiet”:

…Our platoon led the whole company [sic] up this Hill 195 … it was funny, ’cause we were away up, way ahead and the whole unit was coming single file, right, winding behind us. Well, we went up and we were clipping wires and things on the way up, so the Germans weren’t getting messages back. And we went up right through the Germans, okay. And we got up, and we got to the hill, we’re listening and here’s the unit, everybody’s supposed to be quiet, right, and here’s the unit coming up with I don’t know how many hundred men, okay, coming up this hill behind us, and we could hear the shovels hitting the rifles and things like that, you know, and they were supposed to all bemuffled, but with that many men…

“Get a job done; save lives”

The first attempt to take Hill 195 failed with heavy casualties to the BCRs and the Algonquins. Lt-Col Stewart’s plan resulted in success – they took the hill – with no casualties until the next day. It fit perfectly with his summation of the moral trust at the heart of command – “Get a job done; save lives.” The German counter-attacks, which he had anticipated, were repulsed. German shelling took the lives of Lt Boyd and Pte Richard McDonald. For Maj Maclean, the Argylls’ “intense group loyalty” took flame at Hill 195. Dave Stewart’s and the Argylls’ military reputations took root (or flame) at 195 as well. Historian LCol Brian Reid considers “Dave Stewart’s infiltration … onto Point 195” as one of the examples of “the warrior spirit.” His other examples were at the section or platoon level, 195 was a battalion-level example. Historian Terry Copp considers Stewart’s leadership, along with that of Lt-Col “Swatty” Wotherspoon of the South Alberta Regiment, “outstanding.” Historian LCol John A. English described the Argylls’ action at 195 as “probably the single most impressive action of ‘Totalize.’” There are plenty of plaudits for Argyll success at 195 and some belong to Capt Johnston and the soldiers of the Scout Platoon one of whom was Pte Paul Cole.

Some of the Scout Platoon, France, 1944. Back row: 2nd from left, Pte Fred G. Cooper; 4th from left, Pte Jim Crawford (with the bottle over his head); 5th from left, Pte Tony Mastromatteo (holding the bottle); 8th from left, Cpl Gord Boulton. Front row: 1st at left, LCpl Lloyd Martin. Lt Mac Smith (IO and then Adjt) wrote of Capt Lloyd Johnston that he was “about the best officer in the C.A.O.” and “has a platoon who can smell out Gestapo headquarters from any direction and who return laden with strange souvenirs like the occasional bottle of Cointreau, Benedictine or Triple Sec.” This image supports Mac Smith’s assertion!

“a platoon who can smell out Gestapo headquarters from any direction”

Lt Mac Smith became the Intelligence Officer after Lt Boyd was killed on 10 August. He then succeeded Capt Don Seldon after he was captured at Igoville, France, on 27 August. Four days later, he wrote his wife about the unit’s various diversions amid battle and Johnston and the Scouts figured prominently:

… you were saying how strange it is that my letters are so cheery. My bird, if you didn’t preserve your sense of humour around these parts you would go about beating your head against trees. In addition to the usual unpleasantness of having diverse bombs, shells and bullets flying about from time to time, my associates are sufficiently screwy to justify me departing a trifle from the norm. For example, we captured an objective last week after some effort, about 7 o’clock. At eight we were eating corn on the cob, sliced tomatoes, and the usual stew enlivened with new potatoes, carrots and beans. Our foragers have two objectives – the military one and the gastronomic one. The decimation of chickens as a result of poorly aimed mortars is rather remarkable, too. My man Johnson [Lt Lloyd Johnston had the Scout Platoon], who is about the best officer in the C.A.O., has a platoon who can smell out Gestapo headquarters from any direction, and who return laden with strange souvenirs like the occasional bottle of cointreau, benedictine or triple sec, or as [a] last resort a case of Calvados which is the local cognac and will burn freely in cigaret [sic] lighters…

From 29 July to 7 September, the battalion lost 84 KIA, including 1 major, 6 lieutenants, and 6 NCOs; the wounded numbered 229, including 3 majors, 2 captains, 7 lieutenants, and 11 NCOs; the POWs were 20, including 1 major, 1 captain, and 3 NCOs. The total was 333 struck off strength between 29 July and 7 September! The battalion’s establishment on 26 July was just over 800; its fighting strength 400 to 500. B and C companies sustained such heavy losses that they were amalgamated into one company following their action at St Lambert (see ASgt Cecil Fisher, Pte Ira Hedman, and Pte “Pop” Burrill). For the most part – there were exceptions such as Pte Josef Poniedzielski – the casualties were from the original Argylls who enlisted in 1940 or 1941 or the large tranches of reinforcements who arrived on 5 July 1943 or 2 October 1943. In short, they were well-trained soldiers at every rank level. The first reinforcements arrived on 4 September and the number was “sufficient” for the battalion to revert to four rifle companies rather than three. The 81 reinforcements who appeared on 12 September such as Pte Gordon Douglas Marr were “much needed” as those who came later in the month such as Pte Alexander Nickoloff.

The losses, of course, continued with the fighting. What Capt Claude Bissell called the “shadowy company” of the dead grew almost continuously in numbers. In September that company drew new recruits from the Scout Platoon. At Moerbrugge, Belgium, from the 8 to the 10th September, the Scouts were part of a diversionary attack north of the village. On 14 September 1944 Capt Johnston was killed by heavy enemy fire just outside of the battalion’s command post at Moerkerke. He was revered and, as Cpl Boulton declared, they all wept.

“after some hard fighting”

In the early morning of 19 September 1944, Lt-Col Stewart “announced … his intention” to attack Sas van Gent, “a fairly large town just inside the Dutch border, on the Neuzen canal.” By 1900 hours, “after some hard fighting,” the Argylls took the town; they suffered three killed in action and six wounded: Pte Paul “Cosy” Cole was among the dead.

“a German sniper over here machine gunned and got Cole”

Pte Jim Doyle of the Scouts recollected Cosy Cole’s gruesome death. Doyle misidentified Crawford as “Junior,” a nickname for Pte Clarence A. Crawford, an original Argyll like Doyle. Junior Crawford served in the Transport Platoon. In fact, Doyle is referring to Pte Jim Crawford:

…we were going up the railway track. The officer and I and [Pte] Cole – who was seventeen – and [Pte] Junior [sic] [Jim] Crawford. And they’re [Cole and Crawford] on that side of the track … and we’re walking up the track. And there was a German over here waving up a white flag. So we’re standing up and we’re waving him in. Meanwhile, a German sniper over here machine gunned and got Cole – machine gunned his head off … Now, they fell on that side of the track and we fell on this side. There’s a little bit of a ditch. Junior [Jim] Crawford was in the ditch with Cole’s dead body. It must have been awfully nerve wracking for that boy; he was only eighteen himself, if that. And the officer and I were back on this side. And we felt we’d really been conned … here we’re waving this guy in and we were set up. But we were pinned down, so we got the German … back – we figured they wouldn’t fire at him … And anyway, we managed to get back. We crawled down the ditch this way and crawled out, and we finally got back. And the carrier went up to get Crawford and Cole’s body. Meanwhile, the German soldier was dead over here. I don’t know how, but he looked like – well, enough said.

“adorned with plants and perennials”

Liberated Belgians immediately recognized Pte Cole’s sacrifice, like that of LSgt Jess Grey, who was killed the previous day, as one of their liberators. On 11 January 1945 Padre Charlie Maclean wrote the Grey family that “the people of the town have taken up an offering and with funds have made provision for flowers to be placed on your husband’s and Pte Cole’s grave every second day for the next three years. They did this as a token of thoughtfulness for the liberation…” The Belgian Legion of Former Soldiers (1914–18 & 1940–45) in Zelzate took notice as well and held a ceremony there on 5 May 1945. They sent a “narration” of the event written in French to DND headquarters where it was translated and forwarded, along with pictures, to Helena Cole, Paul’s mother. It noted that the “tomb is well kept due to the vigilant care of the workers of the hamlet; during the summer, it is adorned with plants and perennials; cut flowers are renewed regularly.” The ceremony commemorated “these two Canadian heroes, on V-Day.”

We practically know nothing of these two young men whose lives came to a sudden end on this very ground. Their names appear on the crosses which keep watch on their graves; we also know that they came from a distant land, Canada, and that they died a hero’s death in the struggle for their country and for liberty for all.

On 3 June 1945 Helena Cole wrote to DND headquarters in Ottawa. She had learned that ASgt Gerald Magee [KIA 18 April 1945] “is dead. I wish to write his mother living in Toronto … as he was the chum of my son Paul Cole who was killed[.]”

“Wreathes [sic] were then laid on the graves of these two heroes”

In September 1945, as Argylls were repatriated, there were ceremonies held in various liberated towns and villages. On the 17th the unit’s war diarist took note a parade honoring LSgt Grey and Pte Cole:

The Canadian contingent was honoured, in Salzate this morning by a special service at the Cenotaph, where plaudits were read by the Burgermaster [sic] and various other civic officials. Local underground leaders were introduced, as well as the two girls who swam the canal on the day of liberation to present flowers to Maj. Paterson and others of C Coy. Also presented was one “Germaine” who aided in evacuating the two Argylls who had been badly wounded and later died. Wreathes [sic] were then laid on the graves of these two heroes – L/Sgt. J.V. Gray [sic] of A Coy and Pte. P.J. Cole of the scout platoon who gave their all for freedom, as the inscription read … The grand parade followed with the Argylls in the lead…

The parade consisted of troops, costumed civilians, bands, and many picturesque floats. The onlooking crowd, numbering up to 50,000 people who had come to Selzate from many of the outlying communities liberated by 10 CIB, and the Poles.

The official ceremony ended at 1730 hrs. with the presentation of illuminated scrolls to Major Paterson … and the playing of no less than six national anthems. In the evening the town was thrown open to the visiting troops. A Ball in the Town Hall, along with all the cafes blended in making a perfect evening, to renew and make more acquaintances…

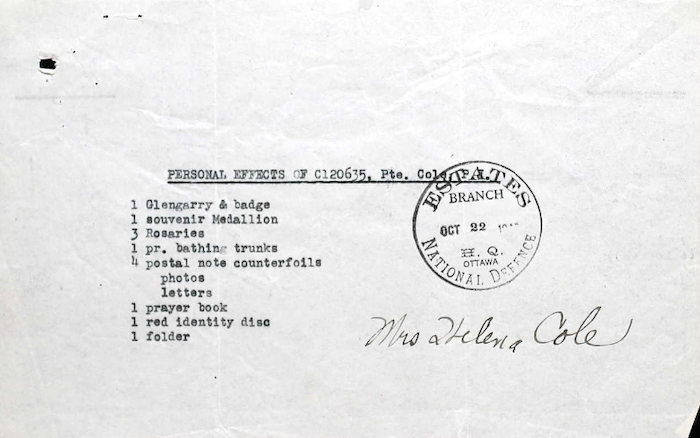

Personal effects of Pte Cole.

“Paul was the one everyone liked”

Paul Coles’ family remember him still and remember him fondly. “Paul was the one everyone liked.” Brenda Ferguson, Paul’s niece, heard the accolades from her father. Paul was “friendly, easy going, [and would] talk to you about anything.” The Coles were “very Catholic, fish on Friday.” They rarely talked about him, but “I only heard fond stories about him.” Paul’s brother, Dave Cole, visited the Canadian War Cemetery in the 1980s “with one of his kids.” The family posted his pictures on the Canadian Virtual War Memorial as well as on Ancestry. Grateful Belgians tend to his grave still.

“Cosy Cole”

Pte Jim Doyle never forgot Cole or his grisly death. It shook Cpl Gord Boulton of the Scout Platoon all his life. In the midst of an interview discussing his wartime experience, Boulton stopped at the remembrance of the fighting that fateful day. He hung his head and uttered but two words – “Cosy Cole.”

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Cole’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

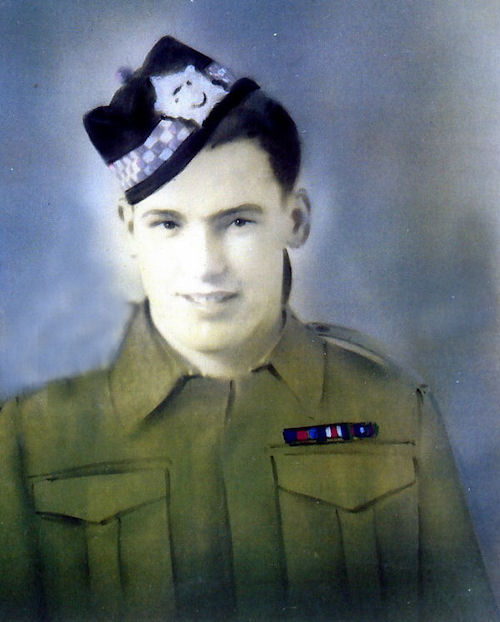

Pte Paul Joseph Cole after enlisting in 1943.

Paul Joseph Cole as a youth.

Cherry Valley Canners cushion cover.

St Gregory the Great Catholic Church, Picton, Ontario.

Pte Cole’s ID card.

Soldiers training at Camp Borden, 1941.

Exercise at Camp Borden, 1941.

Cpl Harry Ruch.

Capt Lloyd Johnston of the Scout Platoon.

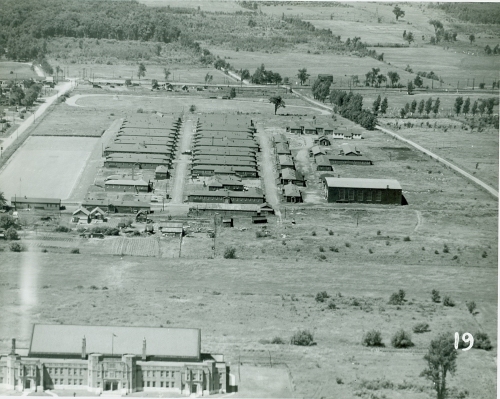

Aerial view of No. 31 Canadian Army Basic Training Centre at Cornwall.

Lt-Col Larose saluting a platoon of trainess at No. 31 CABTC, Cornwall.

Lt-Col Dave Stewart (portrait by Lorne Toews).

Argylls of the Mortar Platoon, autumn 1944. Maj Hugh Maclean thought that, in some form, this photograph epitomized the 1st Battalion.

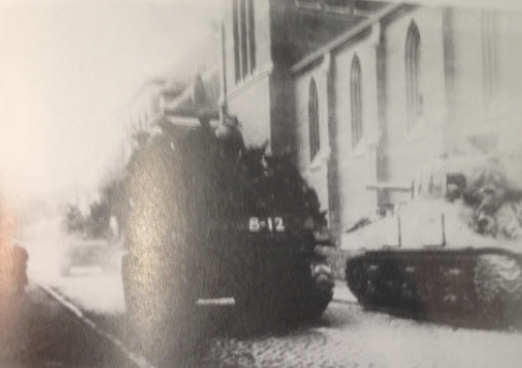

Argylls playing cards beside their Bren gun carrier, Sas van Gent, 19 Sept. 1944.

Argylls on SAR tanks at Sas van Gent, 19 Sept. 1944.

Above and below: Graves of LSgt Grey and Pte Cole at Zelzate.

Above and below: Pte Paul Joseph Cole’s gravestone, Adegem Canadian War Cemetery, Belgium.

Letter of condolence from King George VI.

Cenotaph at Zelzate, Belgium.