Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

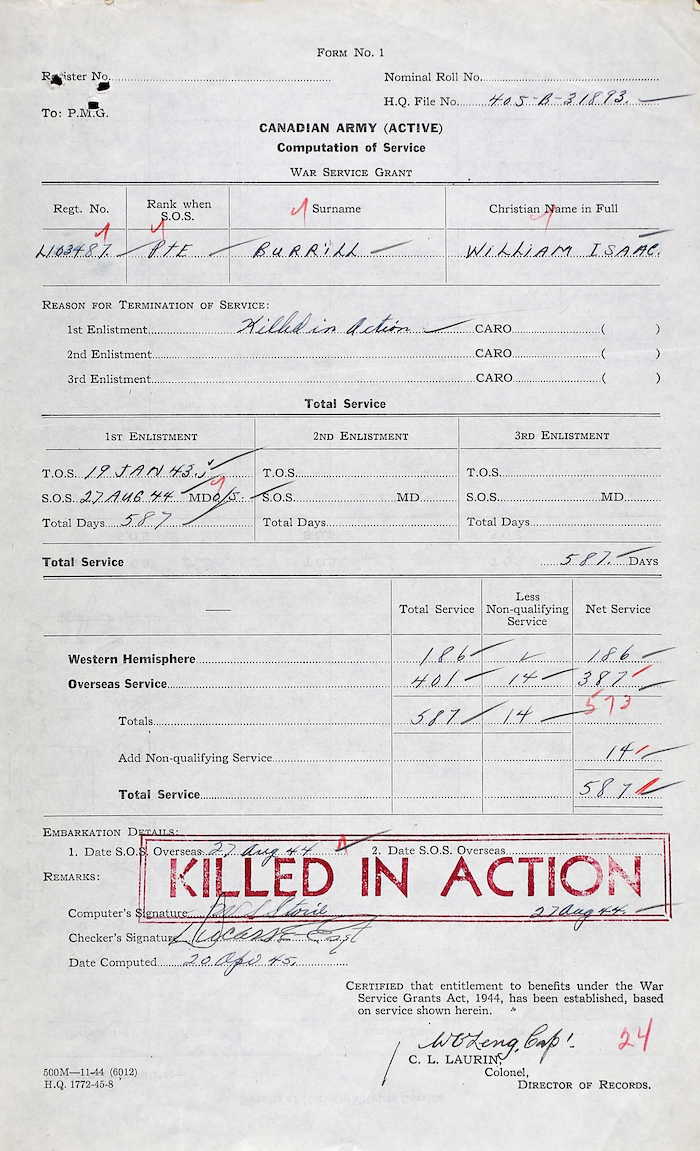

Note on Revised Post: More Information on Pte Burrill (Burrell)

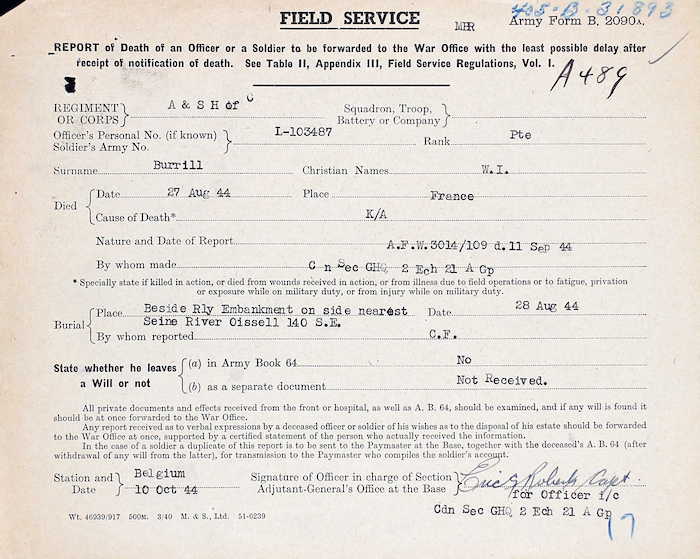

In 2021, I lamented my inability to find an image of Pte Burrill. Recently, I was sent a photo of him and his brother, which has been added at the top right of this page. Earlier this month, I received a welcome email from Elaine Archer with the photo. She explained that her husband, David Archer, had discovered it:

David is working on a project he calls Operation Picture Me. He looks through on-line newspapers searching for articles about the soldiers who went off to war and did not come home. He sends copies of the articles to the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and Find-a-Grave. He noticed a link to Wilbert Burrill’s Argyll history page posted on Find-a-Grave. He checked the history page and saw that you did not have a photo of Wilbert.

I offer my thanks to him and Elaine for contacting us. I have added “Burrell” as a variant of his name.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

29 July 2024

Introduction

Many decades ago, I knew Rudy Horwood well. He was a lovely man, a post-war graduate student in languages and a lieutenant-colonel in the reserves. At the Regimental memorial service for Lt-Col Dave Stewart, Rudy was the parade sergeant-major for the some 160 veterans on parade. His doctor advised him against it because of a lingering heart condition. For Rudy, however, the chance to be on parade once again with the men he had served with overcame all objections. He was buoyant that day. I remember the name “Pop” Burrill because of Rudy’s last memory of him as an old man in terms of young men in their 20s and a man, who at his age, should not have been in the infantry. Pte Burrill was yet another Argyll fatalist, like Pte Chris Jenkinson and Pte Bill Wingate, and death lay waiting. I have been unable, to date, to locate any of his family.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

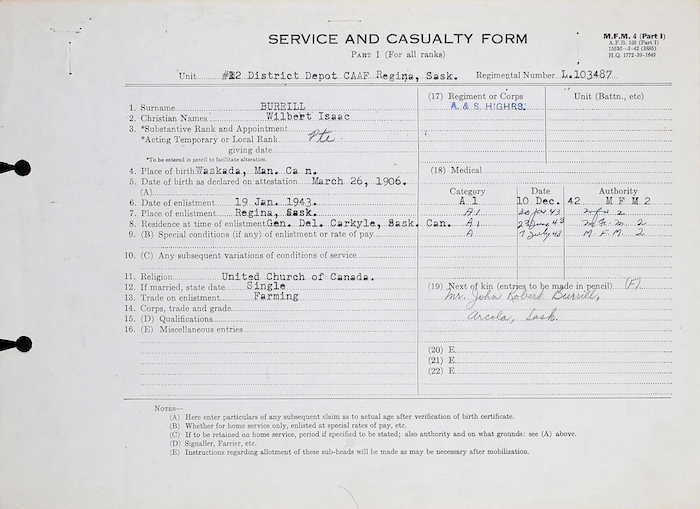

Pte Wilbert Isaac Burrill (1906–44) (L 103487)

KIA 27 August 1944

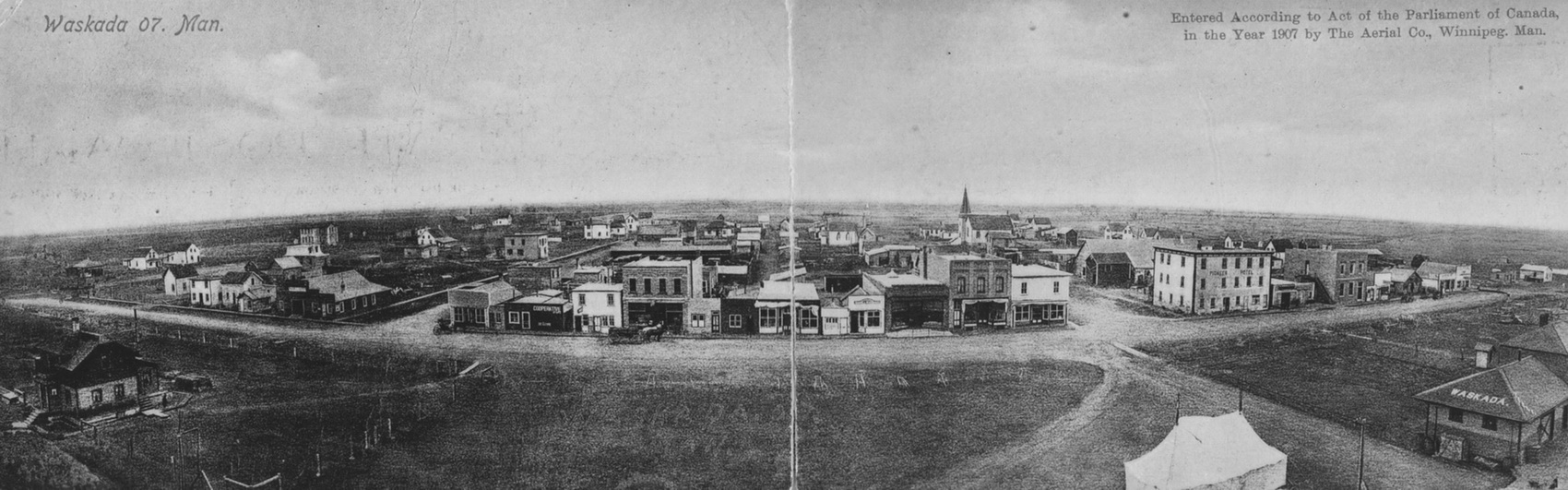

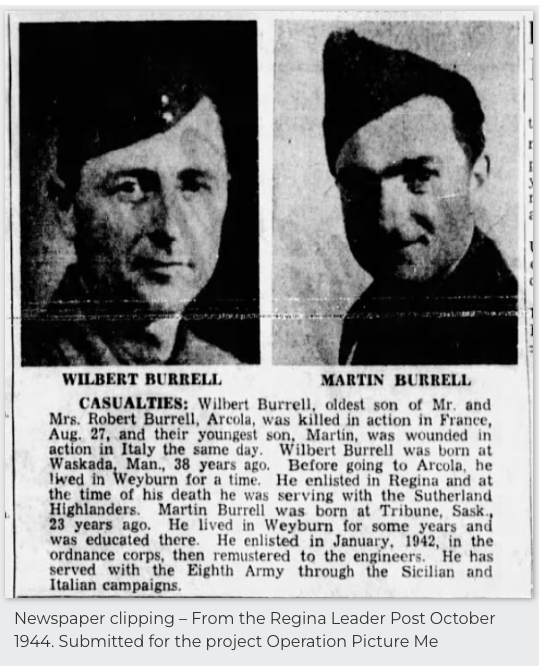

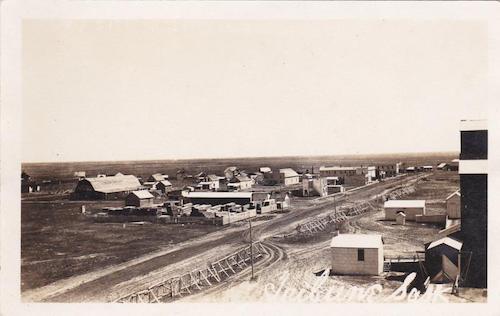

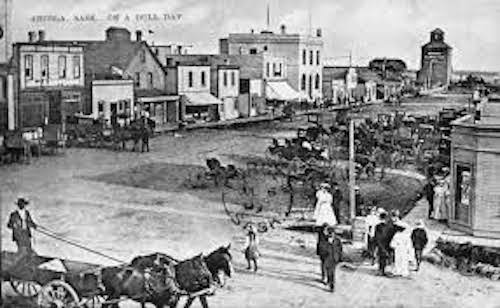

Wilbert Isaac Burrill was born on 26 March 1906 in Waskada, Manitoba, the first son and fourth child of John Robert Burrill (1873–1960) and Almeda Victoria Madole (1879–1974). John was born in Chesley, Bruce County, and Almeda was born in Bruce and living in Chesley by 1881. By 1885, the Madole family lived in Medora, Manitoba. John and Almeda married in Melita, Manitoba, on 11 July 1898, where their daughter Mary Ethel Burrill (1899–1900) was born in August of the following year. By 1903, the family resided in Waskada, Manitoba, a farming community settled in the 1880s and close to the Saskatchewan and American borders. Wilbert and his younger brother, Clayton John (1908–88) were born there. The Burrills moved again, this time to Tribune, Saskatchewan, where Mable Emma Burrill (1911–48) was born. Located in the Souris Valley, it is near Weyburn, where both Robert and Almeda died.

Waskada, Manitoba, 1907.

“Barbering Trade”

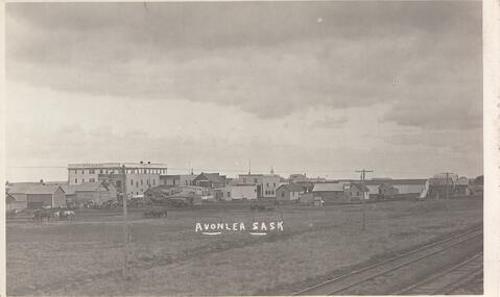

Wilbert Burrill’s army personnel file provides an outline of his life prior to enlistment in 1943. He “quit” the “town and rural school at Tribune” at 14 (about 1920), having completed grade 8; arithmetic had been his “best subject.” He was in the “Barbering Trade” in Avonlea, Saskatchewan, from 1922 to 1929. There, he owned his “own shop” and made $40 weekly. No region of Canada experienced the Great Depression worse than Saskatchewan. It seems likely that it ended his career as a barber. There is no record of his whereabouts from 1929 to 1931, but from 1932 to 1935 he made $15 weekly ranching at the J.J. West ranch in Mountain View, Alberta.

“wheat + other grasses”

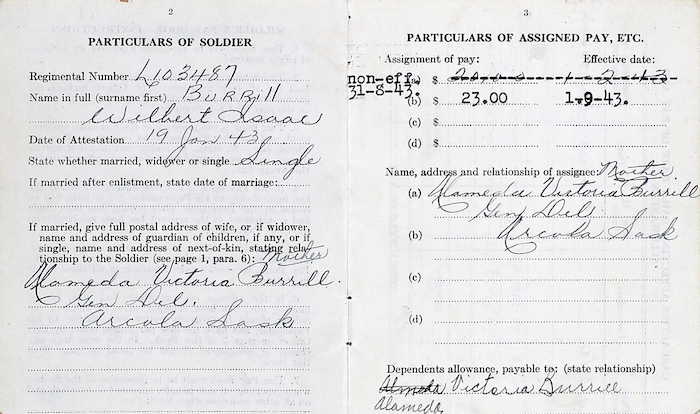

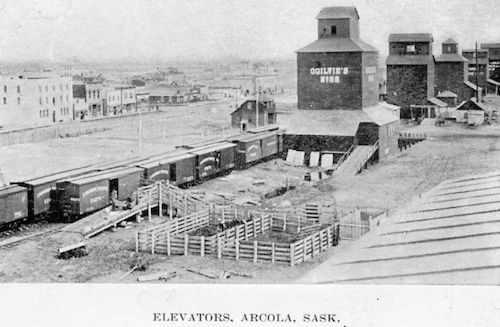

From 1935 to 1943, he rented a farm in Arcola, his “own farm” – the army examiner noted – albeit a rented one, which he worked “with his own equipment with horses and tractor, tractor mostly”; he made $25 weekly raising “wheat + other grasses.” The farm was a three-quarter section of land. “An army examiner noted: “Can drive car. Does own repair work on tractor and car.” Although both parents were living, they were elderly and, at enlistment, it was noted that “recruit has been supporting them for past 10 years.”

“Brothers were in Services” “Duty.”

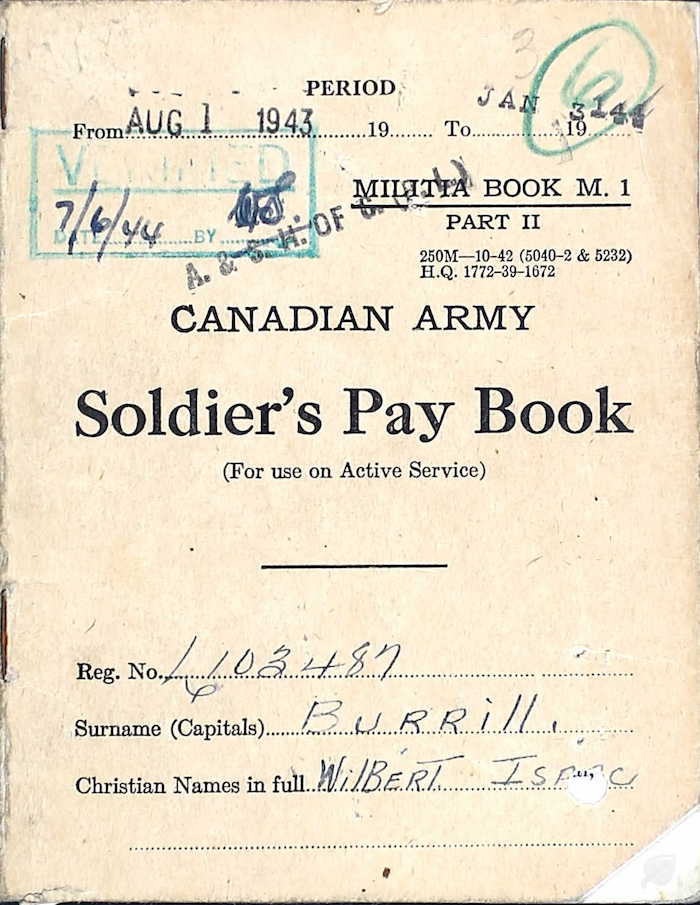

Wilbert Burrill enlisted at Carlyle, Saskatchewan, on 19 January 1943 at a daily rate of pay of $1.30. The support of his parents remained a concern and he assigned $25 monthly to his mother [another record has $30]. As for the reason: “Father is quite aged and unable to furnish support for himself” and “unable to adequately support her [his wife] owing to his extreme age.” The recruiter took note of his “8 years experience as a barber and he “would like own farm in Alberta” after the war. As for other post-war preferences, Burrill indicated an interest in “Wireless.” He had no military background and “enlisted voluntarily.” He read “articles, fiction, current events” and liked outdoor sports such as curling, tennis, baseball, and hunting. The army examiner recorded that he went “to [the] occasional party but mostly in company of men. Took girls out but never very interested.” In 1944, an army examiner listed “Theatres, reading – mostly fiction” as his hobbies. Of his three brothers, one was overseas with the RCE and one in the RCAF (a mechanic); the third had a store in Arcola. His three sisters were married: one lived in Weyburn, the others in Tribune. When asked his reason for joining the army, Burrill replied in 1944 that his “Brothers were in Services” and “Duty.”

“Anxious to serve where best suited”

Pte Burrill was 5’, 10”, 165 lbs, with grey eyes and black hair. He was:

… healthy and strong. Drinks some – heavily in youth but not in recent years. [All in all, he was]: widely read and above average intelligence. Friendly, fluent and stable. Anxious to serve where best suited. Above average attitude. Potential N.C.O. material.

The examiner recommended: “INFANTRY (R) Complete all training. NON-TRADESMAN.”

“pushed us to the limit of endurance every day”

Pte Burrill remained in Regina until posted to Camp Shilo, Manitoba, for basic training on 1 February 1943. Taken on strength at the Canadian Infantry Training Centre (CITC) there on 1 April, he had a furlough from 7 to 20 June and was taken on strength by the Argylls at Camp Niagara on 5 July 1943. He was interviewed on 1 April 1943. The army examiner reported: “Says he can do P.T. and all the drill. Should be potential N.C.O.” His recommendation was “Inf. R. Not tr.” The 1st Battalion had returned from 22 months in Jamaica in May. By 30 June, 129 Argylls had been “struck off strength,” usually because of age or physical condition. On 5 July, the war diarist noted that 152 “other ranks arrived in Camp this afternoon … This draft came from Camp Shilo … by train.” The Argyll welcome included a meal, confirmation of next of kin, and “a V.D. inspection at the R.A.P.” Pte John Booth was part of the Shilo draft. He recalled that at Shilo we “were joined by a large group of men from Saskatchewan who had finished their basic training in their home province”; Pte Burrill was one of them as were Pte James Bannatyne and Pte Lyall Wotton. It was “tough training” at Shilo, Booth remembered:

… the N.C.O.’s had their job to do, they were harsh drivers of men who pushed us to the limit of endurance every day, we ran a lot, it was prairie west of camp … and east of camp it was sand dunes and bush …

The day following their arrival, Lt-Col Ian Sinclair, the commanding officer “addressed the men and posted each man to a company.” Three days later, the unit entrained for Sussex, New Brunswick, and then boarded the Queen Elizabeth for the trip to the United Kingdom, where the battalion disembarked at Gourick, Scotland, on 28 July. The following day, the unit entrained for Camberley in Surrey, about 30 miles southwest of London. There were parades, refresher training, route marches, inspections, night training, and passes. Almost every night and again the next morning, Allied bombers passed overhead en route to, and back from, Germany. Burrill’s pay, like that of so many others, increased from $1.40 daily to the regimental rate of $1.50.

“Little old for infantry … but has good combatant Spirit, somewhat of a fatalist”

Pte Burrill spent his time in England attending to regular military duties, “barbering,” and the “A/TANK Pl [Anti-Tank Platoon”]. In his interview of 4 February 1944, he expressed his preference for this platoon as his desired form of military service. The examiner observed:

Older man, slim, tall build, not very robust. Rather quizzical manner, seems somewhat tense individual who has lived a hard-living + working life. Adventuresome, nomadic spirit, well spoken, alert mentally, high mech. Aptitude. Reads a great deal and has improved his general schooling and knowledge in that way. High learning ability but little ambition to improve his position. Could make N.C.O. rank, but is not interested in applying himself. No complaints, content to let things ride along. Little old for infantry may find rigorous duty too much, but has good combatant Spirit, somewhat of a fatalist.

“But at the end I was feeling fine at being dirty, unshaven”

The letters and reminiscences of Capt Bill Whiteside, who commanded the Anti-Tank Platoon, and Harold Carter, who was in it, provide some sense of the silhouette of the platoon’s life in late 1943 and early 1944. By 20 August, the battalion, including Burrill’s platoon, received “additional weapons.” Pte H.E. Carter considered the arrivals “a welcome change … maybe we’re getting somewhere in this army,” he thought, “if they plan to gave us a few guns and equipment to move them with …” In early September, the battalion moved to new quarters in New Hunstanton, a seaside town in Norfolk about 102 miles NNW of London, for collective training. The battalion also welcomed its new commanding officer, Lt-Col J. David Stewart, who arrived on the 27th. LCpl Carter wrote to his parents on 1 October 1943 that at Hunstanton the days “were sunny, cold and uncomfortable. We move south from there with no regrets.” He describes the 4th Division’s exercise in late September on a:

… 7 days scheme … the first few days were rotten, food was lousy and none knew what was going on … we get soaked, sleep in sodden blankets, get awful grub and then they wouldn’t let us wear raincapes. But at the end I was feeling fine at being dirty, unshaven …

“the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment”

The same day, the battalion moved to Riddlesworth Camp in Norfolk, which Pte Booth described as “the dirtiest camp we ever moved into and it took plenty of work to make it fit to live in.” Here, there were movies a couple of times weekly as well as bingo games, sing-songs, and other forms of entertainment. Cigarettes were rationed, 40 per day per soldier. There were brigade exercises, company dances, and a divisional exercise. “I don’t think,” LCpl Carter wrote, “I spent a more miserable time in my life.” For Capt Bill Whiteside, the Anti-Tank Platoon’s officer, “living in the open was … very important. And from every point of view: supply, living conditions…. Living in huts … doesn’t really come too close to being the real thing.” On Exercise Bridoon in early November, “in the opinion of the Umpires our Anti-Tank and Piat guns had neutralized the enemy armour and any further advance by [their] unsupported infantry would have been suicidal.” On 4 November, with “the ‘war’ [Bridoon] over,” Argylls made bonfires, sang (accompanied by mouth organs and one guitar). The war diarist observed that “Argyll sing-songs have a peculiar character of their own … the selections range from Scottish ballads to Jamaican folk songs … and abetted by the soft glow of a camp fire they have a quality that perhaps best expressed the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment.”

“All there is to do is get drunk and go to movies”

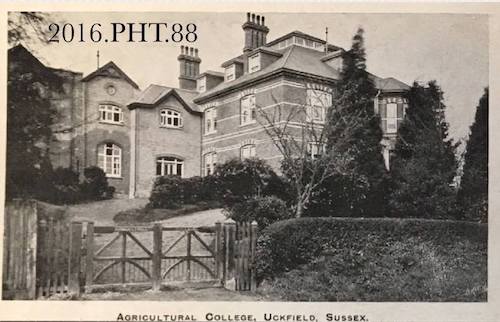

Two days later, they moved to Uckfield in Sussex. The companies were billeted in different locations. Support Company, which included the Anti-Tank Platoon, was quartered with Headquarters Company in St Michael’s College “in the town.” LCpl Carter opined to his parents that “we’re getting to be more and more like a travelling circus.” That said, the “barracks are quite good – there’s steam heat, bath tubs and showers.” There were company parties, leaves (with Scotland as the destination of choice), a “retreat” played by the “Pipe Band” for the first time since the unit’s arrival in England, range work, and an ever-increasing tempo of training. On 21 December, the unit’s various companies spent time “in mastering the new Anti-tank weapon known as the Piat gun.” At Christmas, the Argylls hosted a part for “150 orphan children.” Argylls received parcels from home and from the Women’s Auxiliary. There was a fine Christmas meal. On Christmas Eve, LCpl Carter “went out … and got good and drunk … All there is to do is get drunk and go to movies.”

“The platoon is enthusiastic … and feel they are quite capable of taking on the real thing”

The Anti-Tank Platoon “used to go down to Beachy Head … quite a lot” and use the ranges against a “big framework of a tank” pulled back and forth on a railway cart. “The boys,” Capt Whiteside noted, “pop off a fair amount of ammunition.” For his part, Carter wished that they had more ammunition, more shooting, more practice, and more targets. On 2 January 1944, the war diarist wrote that the reports had arrived regarding the platoon’s exercises in Kent. On the first day of competition against other units, the Argylls were “in the cellar position” but then “reversed the pattern at the finale to finish on top. The platoon is enthusiastic about the practices and feel they are quite capable of taking on the real thing.” The platoon accompanied the battalion to Scotland for two weeks of intense training and getting wet in Inverary. It returned to Uckfield, where there were inspections by General Montgomery and King George VI as well as training in street-clearing in “pretty knocked-down houses” in London.

“I think I’ll get killed; I’m sure I’m going to get killed”

On 24 April, Capt Whiteside participated in a TEWT (training exercise without troops) organized by the 4th Division’s commander, Maj-Gen George Kitching, for the provision of an anti-tank “screen covering any attack.” “There was,” Whiteside thought, “no reality to it. We didn’t realize the hitting power of tanks until we were actually with them in the field [i.e., in action].” The 17th of May brought another inspection. Prime Minister W.L.M. King inspected the division. For Sgt Rudy Horwood of the Anti-Tank Platoon, the memory was “most vivid” and not pleasantly so. They waited about four hours, hating every minute, until King passed by in a jeep “and away he went.” On 5 June, Whiteside took the platoon to Beachy Head (highest of the white cliffs of Dover) “for a practice shoot.” They did not shoot, however, and prohibited from leaving because there were “all sorts of interesting things happening in the Channel.” Sgt Horwood remembered that “some of the people in the Platoon were very, very disappointed and upset that they weren’t there [in Normandy on D Day]” and a couple of them “got drunk.” For his part, LCpl Carter did not share the disappointment: “We’d seen enough of those accounts and movies of beach battles, and they’re not the nicest thing in the world.” As the battalion waited for its turn, training was reduced “mainly” to route marches, cleaning weapons, and waterproofing vehicles. With embarkation for France now on the horizon, LCpl Carter thought: “I think I’ll get killed; I’m sure I’m going to get killed.”

“I mean you look for the nearest Hole … that’s when I realized it wasn’t a game anymore”

Normandy was warm and the battalion soon had its first taste of war. A bomb fell in the battalion area on the 27 July, and it moved into Caen on the 28th. LCpl Carter “couldn’t imagine anything getting completely obliterated the way it [Caen] was.” Pte Clare Huffman remembered “the rubble and the destruction … really made an impression on what war was really like. Others recalled the “stench.” Pte Bob Post said, “I can still smell it after forty years.” The “whole area smelled … from the people killed and the cattle” was how Pte Orville C. Taylor put it. On 29 July the battalion had its first two casualties. CSM George Mitchell, C Company, wrote in his diary: “First casualties – P.Hindle – McCann. Coy despondent – realize it’s war. Enemy shelling hot and heavy.” The losses had their effect on LCpl Carter:

For want of some other word … scared. I mean you look for the nearest hole … that’s when I realized it wasn’t a game anymore … I guess I was scared.

Pte Burrill embarked for France on 20 July and disembarked there two days later. On 3 August 1944, Horwood sent a truck from B Echelon to pick up the Anti-Tank Platoon’s “big packs” from a slit trench in Bras. Pte Lyall Wotton was one of the three or four from the platoon on the truck: “As soon as the truck reached the place … the Germans had seen the Dust and they put in a couple of 88s [artillery rounds]. And the first fellow in my platoon … was killed. He was nineteen.”

Anti-Tank Platoon, 1944. Pte Wotton indicated his closest friends by marking them with an X.

The Anti-Tank Platoon played a notable role at Hill 195 in destroying enemy counter-attacks (see Lt Milt Boyd). Pte Burrill played his part.

Pte Burrill was killed at Igoville on 27 August 1944. Lt Claude Bissell, the unit’s Intelligence Officer and war diarist, wrote:

At 0900 hours the leading elements crossed the Seine. The objective … was Igoville, and the high ground to the right and behind it. The Algonquins met with considerable opposition, and consequently we were ordered to attack and form up in the Igoville area only. While we were waiting to pass through the Algonquins we were heavily shelled and machine-gunned from the high ground to the north, suffering some casualties. The attack on Igoville went in at 1500 hours, “B” and “C” Coys. leading, supported by “A” and “D” Companies. Very heavy opposition was encountered, but the objective was successfully taken and consolidated by 1800 hours.

Just prior to the attack going in, the B.H.Q. group, including the Adjutant’s half-track and the Signals’ carrier, were, in some unknown manner misdirected down the main road and entered Igoville, while the latter place was still in enemy possession. Three members of the group managed to escape, two were killed, and the balance, 15 in number, including the Adjutant Captain Seldon and Major Lillie, were presumably made prisoners [they were].

The Battalion suffered 75 casualties in this action. Lt. Henderson was killed when he attempted to deal with enemy snipers. Lt. Phillips and Sgt. Jackson of the Carrier Platoon were killed during a “Cavalry Charge” through a field that was giving concealment to enemy snipers. Forty prisoners were taken, and an equal number of enemy were either killed or wounded.

There were 13 KIA, including Pte Burrill and Pte Joe Bearss. There were 45 wounded and 16 POWs.

“Pop Burrill was dead. But he was the oldest guy.”

Sgt Rudy Horwood, Anti-Tank Platoon, had vivid memories of the action:

…my guys were lying down along the railway embankment, and we had a little bit of mortaring – not very much – from the Germans … And so when we got the orders to move, I was waking up the guys who were asleep. And I kicked [Pte Wilbert I.] Pop Burrill on the bottom of his boots to wake him up. He didn’t move, and we looked at him. We couldn’t find anything wrong with him, and he was dead. He’d been hit right through the top of his helmet – a little piece of shrapnel went right into his brain. And he was the only casualty. We never even had a person wounded, and Pop Burrill was dead. But he was the oldest guy. He should never have been in the infantry at thirty-six … everybody called him Pops because he was an old man in our terms.

HCapt Charlie Maclean buried Pte Burrill the next day “Beside Rly [railway] Embankment on side nearest Seine River.” He left almost nothing by way of personal effects: 1 Glengarry, a wallet, 3 handkerchiefs, a “Photo Case & Snaps” and a souvenir. He had a bank account at the Royal Bank in Arcola, which contained “fourteen dollars + few cents.” He willed his estate to his father.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Burrill’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Brothers Wilbert and Martin Burrill (Burrell), Regina Leader Post, October 1944..

Waskada, Manitoba.

Old and new schools in Waskada, 1906.

Tribune, Saskatchewan.

Avonlea, Saskatchewan, 1912.

Arcola, Saskatchewan, 1908.

Arcola, Saskatchewan, 1914.

Grain elevators, Arcola, Saskatchewan, 1906.

Beachy Head, East Sussex, England (photo 2011).

St Michael’s College, Uckfield, England.

6-pounder anti-tank gun.

17-pounder anti-tank gun.

War memorial in Arcola, Saskatchewan.