Introduction

I first came to know the fallen of 1944 and 1945 through the veterans who provided critical assistance to the Black yesterdays project. My friend Pte John “Mac” MacKenzie left me with lasting impressions of some of his friends in D Coy who had died overseas. Chris Jenkinson was one of them and his story is a haunting one, as are those of the other Argylls killed at Moerbrugge: Pte Johnny Sawyer, Pte Adolph O’Back, and Cpl Bill Hollinsworth.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Moerbrugge: Day Three

10 September 1944

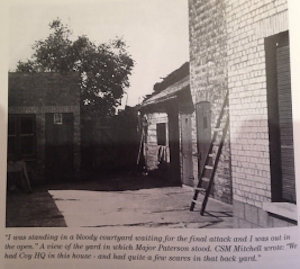

Maj Bob Paterson, CSM George Mitchell, and the men of C Coy, including the wounded, waited for the end; they had almost no ammunition save the rounds for Paterson’s pistol: “I had thirty men, and they were all there. You didn’t have to give any orders. They were going to fight, they were all going to fight…. Never thought of [surrendering]. Never entered my mind. Didn’t enter [CSM] Mitchell’s mind. Didn’t enter any of the men’s minds, that I know of … I thought that was the end…. [But] I think I was too exhausted to be afraid … I was fatalistic at that point. I’m no hero. I was no hero at all … there were no heroics in my mind. I was beyond that point.”

Instead, they heard the faint rumbling of the SAR’s Sherman tanks, which brought relief. The picture of Pte Gord Franks of C Coy, below, provides immediate appreciation of C Coy’s joy. As LCol Dave Stewart said, “it was a gritty performance” and then some!

Pte Gord Franks, C Coy, Moerbrugge, 10 Sept. 1944.

Over three days, this under-strength infantry battalion had 13 KIA, 50 wounded, and 12 POWs. On the last day – the 10th – there was one KIA, Pte Chris Jenkinson, and two wounded. Chris’s story is told in the text below for his Argyll poppy.

From Black yesterdays: the Argylls’ war (1996)

War Diary. 10 September 1944. Moerbrugge [C.T.B.]

“By early morning the bridge was completed and the S.A.R. tanks began to cross. With their assistance the Companies finally consolidated their positions…. Prisoners began to come in, their numbers amounting to 150 by the end of the day, among them several officers. All prisoners were from … 64th. Division.”

Moerbrugge bridge, 10 Sept. 1944.

“Enemy mortaring and shelling … continued during the day, making a move by ‘F’- Echelon impossible. Since considerable confusion had prevailed between the Argylls and the Lincoln and Welland in the disposition of the Companies, the C.O. ordered that our area should be confined to the rectangle formed by the roads to the left of the place of crossing.”

[KIA: Pte Christopher Jenkinson. Wounded: 2.]

Relief

Major R.A. Paterson, The Tenth Canadian Infantry Bde (1945)

5/8/2020 75th Anniversary, Moerbrugge: Part 3

“By midnight, our counter battery work caused the shelling to ease enough for bridging to be resumed, and at 7 o’clock the morning of the 10th the first tanks of the South Albertas’ A squadron were rumbling up the tile, brick and glass littered street. The practically given up for lost defenders of those pitiful left and right companys [sic] could hardly see the Shermans for the tears of relief flooding their eyes. It was a great moment, a miniature Lucknow, but instead of the faint skirl of pipes, it was the distant muttering of a Sherman that tormented the overwrought imaginations during this two day seige.”

Maj R.A. Paterson

Interview. Pte Anonymous. 18 Platoon, D Coy

“Those engineers did a terrific job, putting up that bridge. They had a helluva time because they were firing right on the bridge site, and they had so much fire they had to halt it for a while. But when those tanks rolled over, there was a great sigh of relief. And we were thirty-eight all ranks in the Company by that time – that’s including clerk [and] shoemaker.”

Interview. Lt Claude Bissell. IO

“It was terrible. Well, anyway … there always seems to be a miracle. At a certain stage, you feel everything’s lost. The Battalion’s been lost – it’s been counter attacked and wiped out…. But then somehow or other the engineers got up and got their bridge across, and the tanks moved over.”

Courtyard where C Coy waited for the final attack, Moerbrugge, 10 Sept. 1944.

Interview. A/Major Bob Paterson. OC, C Coy

“You could hear the [SAR] engines start up … and we knew they were coming. And Jesus, what a glorious moment, I’ll tell you.”

Interview. Pte Gord Franks. C Coy

“Thirty-six of us got out – of the whole Company, thirty-six men.”

Reflections

Interview. Lt-Col Dave Stewart. CO

“… a gritty performance.”

Major R.A. Paterson, The Tenth Canadian Infantry Bde (1945)

“Various estimates have been made but it is quite reasonable to say that approximately 700 Germans were killed, captured or wounded, that 20, 20 millimetre flak guns were captured, that six 8 cm mortars were taken, and one German SP knocked out (by the 29th Recce) in this little remembered crossing of the Ghent Canal.

It thus appeared that the great breakout run, the days of quick, joyous liberation, had ended. This last had been a costly, grim, and bloody action against an enemy who composed the main part of the powerful regiment that repulsed the entire Third Division for so long on the Leopold.”

Interview. Pte Gord Franks. C Coy

“I never seen anything like it. I didn’t think we’d get out of there alive, but we did.”

Pte Christopher Denis Jenkinson, 1st Bn Argylls (1908–44)

KIA 10 September 1944

“Sing me a song of a lad that is gone”

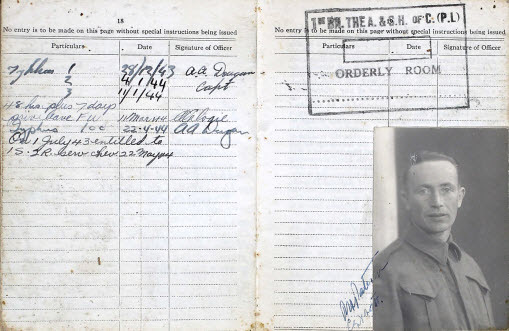

Chris Jenkinson was romantic, poetic, and ironic, something of a puzzle for non-Regimental army officers conducting personnel interviews. Soldiers’ entries in their service books were rare and usually prosaic, but not Chris’s! In his service book, he scribbled these words from the “Skye Boat Song” on a blank page after the section on wills:

Sing me a song of a lad that is gone

Say! Could that lad be I

Merry of soul, he sailed on a day

Over the sea to Skye

Give me again all that was there

Give me the sun that shone

Give me the eyes, give me the soul

Give me the lad that is gone.

“He is a good educated Irish Catholic and that’s something”

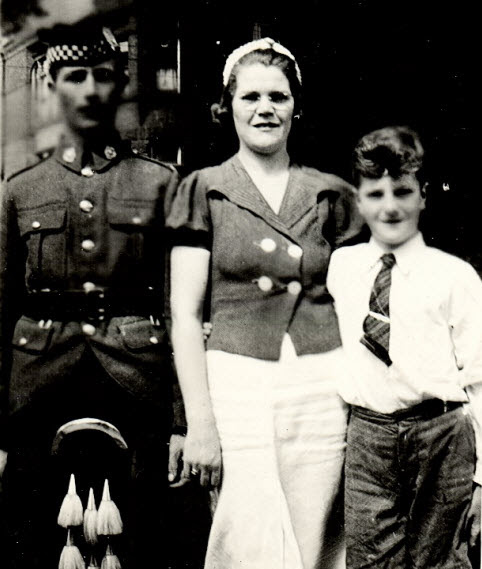

Chris was born in Arklow, Wicklow, Ireland, on 30 June 1908. His father died in 1910, and Chris was raised by his mother and stepfather; he had three brothers and two sisters. He left school at age 13 after 8 years and moved to Canada in 1925. He trained as a barber and hairdresser in Toronto, working at various shops in Ontario, B.C., and Quebec for more than 17 years, probably for the CPR chain of hotels, including the Royal York. At the time of his marriage to Monica Ford (1908-89) in 1937, he was living on a rented farm in Orangeville. The wedding took place in St Michael’s Cathedral, Toronto. Monica’s mother took off her glasses for the wedding picture: the “proud look is for her new son-in-law. He is a good educated Irish Catholic and that’s something.”

“for adventure”

Chris’s favourite sports were water polo, softball, and volleyball; his favourite pastimes were “attending shows and reading magazines.” On 1 January 1940, he enlisted in Hamilton with the Argylls “for adventure.” He was 5’, 7½”, 126 lb, with blue eyes and light brown hair. He started as a rifleman and remained one during his time with the Argylls and D Coy. There were a few minor infractions: AWOL once in 1941 in Niagara, three times in Jamaica, and one charge of drunkenness in Jamaica. His personnel record notes that his attitude to the service was “resigned.” In 01/44, an officer commented on his “soft-spoken and decisive manner.” He appeared “physically fit but complained of lack of stamina due to age. Says he cannot keep up to the young men on battle drill, running etc but is not overly concerned…. Seems rather “browned off” and may be inclined to irresponsibility on that account.” Jenkinson was clearly somewhat of an enigma to such officers. On the one hand, they were impressed by his “keen, active mind and … above average intelligence.” His work history suggested a “yearn for travel” that demonstrated an inability to settle down. On the other hand, in spite of the obvious intelligence, “there is something inadequate about him. It was a hesitant judgement because he was “not mentally dull by any means.” The officer concluded that Jenkinson was “just an example of misdirected effort.” There seemed as well something amiss in the objective picture of Chris’s home life: his son, Walter Forrest, was born in 1930 to Monica. He was “illegitimate”; they married in 1937, and Chris adopted him in 1940.

The officer recommended Chris to be the regimental barber; he had other ideas, however, and remained a rifleman with D Coy. He fought in the minor engagements of early 08/44 – Hill 195, Igoville, and Hill 95 – and met his fate in the grim, costly battle for Moerbrugge from 8 to 10 September. During the battle, the under-strength Argylls had 75 casualties. D Coy suffered heavy losses; Chris Jenkinson was the unit’s only KIA on the last day.

“And I can still see him laying on the cobblestones outside …”

Chris’s Regimental family never forgot him. Pte Mac MacKenzie, D Coy, remembered: “Moose [Pte J.J. Murie] and I carried him out. He died, I think either on the way in or there. And I can still see him laying on the cobblestones outside…. You know, you’d known him since 1940. A married man, kid. Yeah, I can see him laying on his back, one leg bent, his … head fallen back … Moose Murie was on his knees and I was standing there. I don’t know why that sticks in my memory but it does.”

“a living memory as if he was never killed and he never, ever left her”

What was a vivid memory for Mac MacKenzie was a seering one for Monica Jenkinson. The last line of the poem proved to be the epitaph for her life after Chris’ death – “Give me the lad that is gone.” She was stricken by the news. The Argyll Women’s Auxiliary tried to console her; one member recalled how she “wept and wailed.” His niece notes that “when the news came she spent a year in an institution because of shock … He never left her; she carried on and worked at Eaton’s.” Chris Jenkinson “was a living memory as if he was never killed and he never, ever left her.” Niece Monica Christine (named after both of them) heard the stories about him, his love of poetry: “he was talked about almost daily”; she felt she “knew him.” Chris was “the love of her [Monica’s] life and she never remarried.”

“Sing me a song of a lad that is gone”

About 1984, a CBC broadcast on D-Day and the battle for Normandy “triggered a severe response and she lost it.” Monica was found “wandering the streets looking for shelter from the bombs.” She never recuperated and died in Whitby Hospital in 1989 from Alzheimer’s. Son Walter, “who adored the man,” had six sons, one of whom is named Christopher.

With respect – Ancaster Minor Hockey League

Note: Note: Pte Chris Jenkinson’s poppy will be mounted on the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Between 2 and 10 September, 14 Argylls were killed in action (or died from wounds), 48 were wounded, and 12 were POWs.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Christopher Dennis Jenkinson

Jenkinson wedding

Chris, Monica, and Walter, 1940