Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

As is the case with so many Argylls killed in action during the Second World War, I owe my acquaintance with Bill “Fish” Hollinsworth to Pte J.N. “Mac” MacKenzie. I started work on Bill Hollinsworth two years ago and sent a message to a relative. The email address was largely unused, so the reply came months later. Penny Brooks is Bill Hollinsworth’s niece, who learned about her uncle from his beloved sister (Penny’s mother) Rea. Penny has been generous with her time and provided me with images of Bill and his family, five letters that he wrote to his mother and sister, and recollections. John Wilson, Penny’s brother, has also shared his memories of the family and the time.

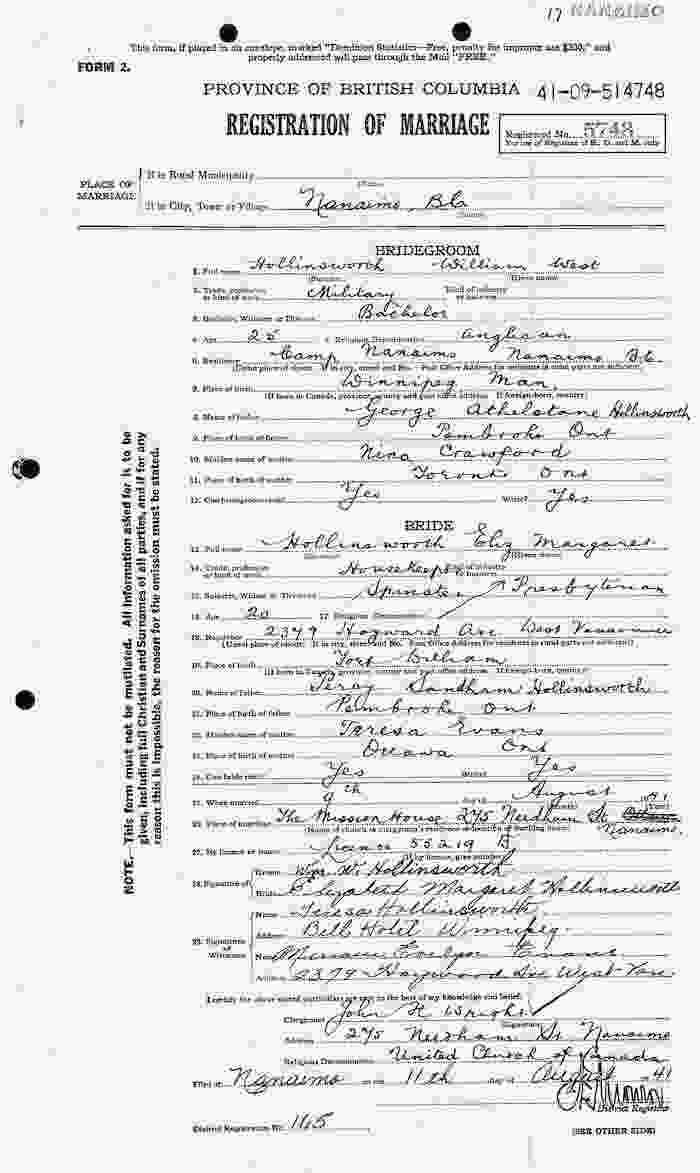

Bill Hollinsworth married his second cousin, Margaret (Peggy) Elizabeth Hollinsworth, in 1941. Peggy’s nephew Harry Hollinsworth shared his memories, as did his sister, Penny Donovan, who also provided an image.

Argyll veterans remembered “Fish” Hollinsworth well. Companionship and brotherhood are good things and an infantry battalion provides just that, albeit in battle, with an edge not experienced or replicated in everyday life. Cpl Hollinsworth died in battle and his comrades-in-arms never forgot him; their memories of him were vivid. Bill Hollinsworth was a name to his nieces and nephews, and his life was rarely discussed. Peggy Hollinsworth (née Hollinsworth) was an aunt and a beloved one to her niece and nephew. Yet, part of her life had boundaries around it and was never discussed. Often, perhaps even most often, families kept their grief silent. In the case of Bill and Peggy, part of the silence derived from the marriage of second cousins. There was no statutory limitation on such a marriage, but there was a cultural one. As Harry Hollinsworth said, “it was a no-no” that almost cloaked completely the knowledge of their brief marriage and shrouded it in mystery.

I am grateful to the Hollinsworth nieces and nephews on both sides of the family for their help in lifting the veil, albeit only partially.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Cpl William West “Fish” Hollinsworth (1916–44) (B 46268)

KIA 9 September 1944

“A look of horror and surprise”

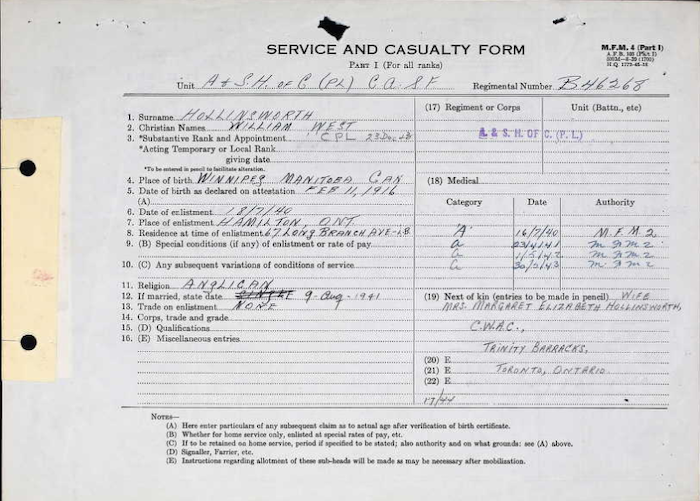

Bill Hollinsworth was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on 11 February 1916, the youngest son of George Athelston Hollinsworth and Nina A. Hollinsworth; they married in Toronto on 21 December 1908. He grew up in Long Branch, Ontario, with his two brothers and sister, completing grade 10 at an “urban, academic” school in Long Branch in 1936–37; he then took a commercial course for one year. He had done “odd jobs” for two years and was a “dress salesman” for six months. For three years prior to his enlistment, he was a surveyor for the Ontario Hydro Commission.

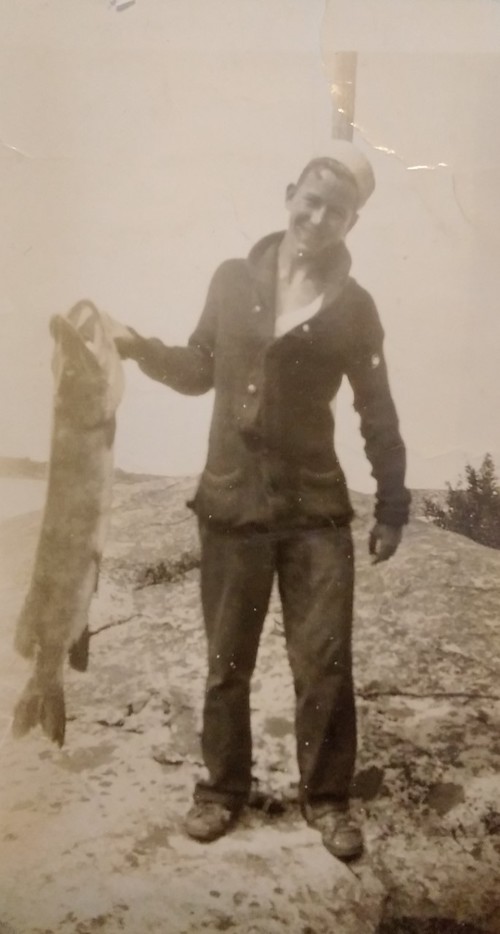

When his father, George, found work in Toronto, the family moved there. Initially, they lived with Nina’s older sister, Hatti Armstrong, a widow. She owned a cottage at Bluff Point, Port Severn, and summers from 1919 on were spent there. The Hollinsworth kids spent all of the summer breaks there. Bill, apparently, loved it. He particularly enjoyed fishing and later acquired a nickname associated with his passion for that pastime.

“To do a job”

Bill Hollinsworth enlisted with the Argylls in Hamilton on 18 July 1940. When asked in January 1944 why he joined, Hollinsworth replied: “To do a job.” He was 5’, 6’, 130 lbs, with fair hair and blue eyes. He adjusted well to the army and the initial period of adjusting to military life and discipline. The first 10 months were spent in Hamilton, various spots in the Niagara peninsula doing guard duty, and Niagara Camp. He was hospitalized for 12 days in November 1940 with influenza. The Argylls entrained for the military base at Nanaimo, British Columbia, in May 1941. The battalion arrived on 25 May and left on 15 August. The sights enchanted many Argylls. Pipe-Major Frank Noble wrote that “the first sight of the mountains close up makes you feel weak at the knees + infinitely small.” Lt Paul Winchester, the unit war diarist, opined: “The camp is all that could be hoped for. The country is to say the least magnificent.” Camp Nanaimo was still under construction. Some of the facilities for advanced training “have as yet not been supplied to this camp” and the rifle ranges “are under construction.”

“Wine, women and song”

There was “company drill” and “daily marches” aplenty. In off-duty hours, many Argylls “devoted their time to mountain climbing and deep sea fishing.” By the end of May, the Argylls instituted a new system of weekend passes, a measure that “sharply decreased” the instances of AWOLs. Pte Les Entwhistle, Signals Platoon, enthused about the development:

We trained all week and then we used to get a weekend pass every week to go to Vancouver, which was pretty nice … Wine, women and song … Go to dances, and then meet a girl, take her home or whatever …

Vancouver is about 50 miles across the Strait of Georgia from Nanaimo, a journey made possible by regular ferries. The unit received some new weapons (Lee-Enfield rifles and Bren guns), a long march from Victoria to Nanaimo, but little time for field training because of the frequency of inspection parades. By early August, “the rumours started to fly,” recalled Sgt Al Rathbone, D Company, of an imminent move. To the observant eye of the war diarist, “excitement was everywhere.” “It was,” he thought, “welcome news and the men found difficulty constraining themselves. This was their chance, – a chance for which they had waited for over a year.”

“The journey had began”

As the rumours whirled among the Argylls, Pte Hollinsworth had another reason for excitement. At some point during the battalion’s sojourn in British Columbia, he met his second cousin Margaret (Peggy) Elizabeth Hollinsworth (1920–94). Born in Fort William, Ontario, she was living with her older sister, Miriam Evelyn Evans at 2379 Hayward Avenue in West Vancouver. She was working as a “housekeeper,” possibly for her sister. Peggy was the daughter of Percival Sandham Hollinsworth (1877–1963) and Teresa Hollinsworth (née Evans) (1881–1957). They were married on 9 August 1941 at the Mission House in Nanaimo. He was an Anglican, she a Presbyterian; they were married by a minister in the United Church. Peggy’s mother and sister signed the marriage certificate as witnesses. No one from Bill’s family was there; Peggy was pregnant. The battalion held reveille at “0420 hours” on 15 August; there was a muster parade at 0800 hours and the unit “made its last appearance on the parade grounds” at 1115 hours, then marched to the docks. At 1500 hours, the group disembarked in Vancouver, then “commenced its march to the C.N.R. station … The journey had began.” A soldier in the army required permission to marry. Hollinsworth’s was granted on 20 September 1941 while in Jamaica; it was “Eff. 9/8/41.”

William Atholston Hollinsworth

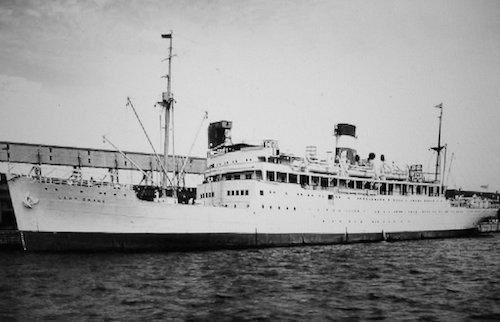

The unit’s journey and the newlywed couple’s journey took markedly different paths. Bill and Peggy never saw each other again. The Argylls returned to Hamilton, but briefly. They were off by train again on 1 September and “embarked aboard the RMS Lady Drake the next day for 22 months in Jamaica.

After the wedding, Peggy Hollinsworth continued to live with her sister. Their son, William Atholston Hollinsworth, was born “at North Vancouver” on 8 January 1942 and died the same day. According to Harry Hollinsworth, Peggy’s nephew, the “baby was still born or died shortly after birth.” Bill was in Jamaica. There is only a single blemish in Hollinsworth’s military career. He went AWOL from 6 to 9 December 1941; he was confined to barracks for two days and forfeited one day’s pay. There is no explanation for it. Absence without leave was a fact of military life, by no means unique to the Argylls. The army considered it a minor misdemeanour, usually punished by confinement to barracks and/or a forfeiture of pay. Hollinsworth’s only infraction occurred a month before the birth of his son. Is it related to the fact? Who knows? There is no surviving correspondence between Bill and Peggy, and there are no memories of the nature of their relationship. Peggy’s niece, Penny Donovan “got a feeling they really wanted the baby, it was good for them but I don’t know.” Peggy’s family knew that there would be a wedding and almost certainly knew she was pregnant (Peggy lived with her sister). Peggy’s mother and sister had witnessed the wedding. Penny Donovan knew her grandmother well: “My grandmother,” she offered, “would never have said a word [about the pregnancy or the fact they were second cousins].” There was no statutory prohibition in Canada on cousins marrying; there was, however, a cultural one. There is no indication that Bill’s parents either accepted the marriage or condoned it. To the extent that there is any indication, they opposed it and Peggy.

At some point after the death of their child, Peggy joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. Government regulations allowed married women to enlist, but only if they had no children under the age of 18. According to Bill’s personnel file, by July 1943 she was serving at Horse Shoe Bay, British Columbia; as of 7 April 1944, she was stationed at Trinity Barracks, Toronto.

Some of the routine of battalion life in Jamaica is covered in Pte Richard McDonald. There are no letters from Bill Hollinsworth while he was in Jamaica. He received six days “Xmas Leave” from 22 to 28 December 1942, which would have been spent on the island. On 17 December, his brother, WO Jack Athelston Hollinsworth, RCAF, was killed in action over Denmark. Like many Argylls, Hollinsworth contracted dengue fever in Jamaica; he was hospitalized from 8 to 14 July 1942 and again from 21 July to 10 August – 28 days in all. The army increased his pay to $1.50 per diem, the regimental rate for a private, on 1 January 1943. He had 14 days furlough from 30 January to 13 February 1943. He was in hospital again in March 1943 for 5 days with yet another bout of the flu.

“quiet-spoken, courteous manner”

The Argylls returned to Canada in late May 1943. At Niagara Camp, on 31 May 1943, a personnel selection officer interviewed Pte Hollinsworth, part of a standard routine for all Argylls eligible for overseas service:

A short well built man (5’6” – 140lbs [he had gained weight since enlistment] of well above average intelligence. This man appears to possess an alert mind; he answers questions in a straightforward way and has a quiet-spoken, courteous manner. He seems to have adjusted fairly well to army life[.] He has had practically no crimes and he seems to have very moderate habits. Hollinsworth plays hockey, lacrosse and baseball, does a fair amount of reading but has few other hobbies. If he displays the necessary leadership ability, he should prove to be good N.C.O. material.

“Psychiatric”: “Tested In Canada June43”

The examiner recommended: “Inf. (Others) Possible N.C.O. material.” Hollinsworth’s personnel form from January 1944 contains this note (and nothing more) under the portion of the form for “Psychiatric”: “Tested In Canada June43.” Psychiatric examinations or notes about them are rare in Argyll personnel forms. There is no elaboration, no clue as to why it was suggested or required. It was not, however, standard and there would have been a reason. What it was is unknown. Whether it related to his marriage and his dead son would be speculation. Hollinsworth received a “Disembarkation furlough” from 1 to 10 June 1943 and another from 24 June to 1 July; presumably he spent them with his family in Long Branch. The train trip from Toronto to Vancouver took four days one way.

The Argylls left for Sussex, New Brunswick, on 9 July 1943; on 21 July, they boarded the Queen Elizabeth for the United Kingdom, arriving in Scotland on the 28th. From there, they went to Camberley, then New Hunstanton, and finally Uckfield. Life there is glimpsed in Lt Milt Boyd’s biography. Hollinsworth was promoted ALCpl on 1 August 1943 (a raise in pay to $1.60 daily); ACpl on 23 September 1943; and Cpl on 23 December that same year (a raise to $1.70 daily). From the time of his promotion to ALCpl, Hollinsworth led a section of one of D Company’s three platoons (16, 17, and 18); he may have been in 18 (his association with Pte Mac MacKenzie, who was in 18).

There are five surviving wartime letters from Bill Hollinsworth: four to his mother and one to his mother. The letters convey something of Cpl Hollinsworth while providing some sense of his mood in the late months of 1943 and early month of 1944. There was considerable self-censorship by soldiers in their letters home in addition to army censorship. There is one critical omission in all five letters; there is no mention of his wife, Peggy, or of the son they lost.

“training the daylights out of us here and it’s no joke”

Bill wrote to his mother on 23 September from “Somewhere in Eng” [Camberley]. He was pleased to hear that she was “having such a good time at the Severn [his aunt’s cottage],” and he wished “I could say the same.”

They are training the daylights out of us here and it’s no joke. We’re just in from five days in the field and will be going out again on the 25th [TAKEX I]. You sleep out on these manoeuvres rain or shine and let me tell you it gets chilly trying to sleep in a down pour without any protection. However they believe in making you hard and they don’t feel six miles an hour is our marching speed and it really makes you grit your teeth.

“a marvelous 7 days leave in London”

I had a marvelous 7 days leave in London. Went to see the Wood’s [family friends] and took one of the boys with me. They certainly showed us a grand time. Say those London tubes are the berries. They sure get you around in a hurry. However the first day we were almost continually lost but had a darn good time just the same. We went to see a good many points of interests including the “pub”. London sure took an awful beating during the blitz.

As yet I haven’t seen Rex [his brother]. It seems he was drafted out of England before I got my leave. It certainly is disappointing when you think he was here almost four years and then is drafted just when I arrive.

“hope those smokes arrive soon”

Boy I hope those smokes arrive soon as I’m getting awfully low. I was told by my officer to-day that I’m getting another promotion. Jackie Singer is barracked just down the road from us but don’t get much of a chance to see him as we aren’t out of the field very long at one time.

Still I guess that’s about all for now as its getting late and I meant to get to bed as I have a dandy cold. Give my best to all and tell that little sister of mine to write once in awhile. So long for now and the very best of luck.

Your Loving Son Bill XXXX

“a fellow in the Company, Bill Hollinsworth”

Hollinsworth did take “one of the boys” – it was Wilf Stone and it changed Stone’s life:

…I was going on leave from Hunstanton – disembarkation leave. I’m sitting on the train in Hunstanton, and a fellow in the Company, Bill Hollinsworth – he was Corporal Hollinsworth – he came on the train. So I asked him to sit down, so we spent the leave together in London. And he said he had to pay a duty visit to see some friends of his, and they had asked him to go out and see these people in Wimbledon … So he asked me if I wanted to go with him, so I did. And we went out there on a Saturday afternoon, I think it was, and he knocked at the door of this house, and a girl answered the door. And he asked for Mrs Woods. So the girl called up, to her mother I guess, and she came down. And Corporal Hollinsworth, Bill Hollinsworth, he introduced himself and told them who he was … and so she invited us in … This woman’s husband used to run dances in London, and so they invited us along. And so we went to this dance, and to make … a very long story short, I ended up marrying this girl [whom Stone met at the dance] … We were married in 1944, in London …

“I’m writing this letter under a truck of all places”

Bill Hollinsworth wrote to his sister, “Sweet Rea,” on 1 November 1943 from “Somewhere in Eng.” [the unit was in the field]:

I’m writing this letter under a truck of all places. However its dry and thats what counts in this man’s army. We are just starting a seven day manoeuvre so that’s how I happen to have my flop under a truck. On the last scheme it rained so hard one night a half a mile over in the next field (any how I did get drenched). [T]he chap who wrote England my England must have been a damn fool or else his old man was a sailor and got tangled up with a Mermaid. After this scheme is over we’ll be going into winter quarters. Somewhere near London I expect.

“got tired of looking at Latin inscriptions so … the nearest pub”

I went to Cambridge on an education tour last Sat. However I soon got tired of looking at Latin inscriptions so I ventured forth to find the nearest pub. The rest of the time was spent testing the quality of their mild + bitters in front of a nice open fire place. Sounds good, eh! Which reminds me we are getting our rum ration in the field now. I usually manage to score three issues per morning. I believe there is a text in the Bible, which says “not to be found wanting.” Well my motto is get plenty of her and you wont be wanting.

“an unfortunate incident the other day”

We had an unfortunate incident the other day [29 October] during bombing [grenade] practice. One of the boys made a bad throw and the grenade hit the top of the bank and rolled back. There were 4 men throwing and three instructors in the close vicinity and the bomb only had a 4 sec. fuse. Sgt [Jock] Rennie of our company jump on it and smothered most of the blast and shrapnel. He was killed almost instantly but he probably saved the lives of several men. It certainly took a lot of “essential guts” to do a thing like that.

“Tell Dad I’d like to hear from him occasionally”

Well Rea I really haven’t much more news. I think your smokes arrived O.K. but I’m not sure yet as I haven’t been able to collect them at our P.O. since receiving a notice of arrival … Tell Dad I’d like to hear from him occasionally. John [his brother] might also loosen up with a letter once in awhile. Incidentally this letter is #2. As all my letters home are no. now regardless who they are to. Let me know which ones you received.

Well I guess I’ll sign off now. Give my best to all at home and I hope that everything is going sweetly. Oh yes! I believe there is one or two old pocket watches kicking around home. I wonder if Mother would send me one as things like that are hard to get here. I need a watch in the worst way. Don’t forget to write soon. So long for now.

Your fond Brother Bill XXXXXXX

“fed up with this climate”

Cpl Hollinsworth (he put “LCpl” on this letter and then scratched out the “L”) wrote to his mother again on 9 December 1943. The Argylls had moved to winter quarters near the town of Uckfield in Sussex, about 60 miles south of London.

I’m just back from whiling away an hour or two in the little pub down the road. We had rather a pleasant evening over numerous light + brown ales. The weather has been particularly miserable these last few days. I’m sure getting fed up with this climate and if I ever get out of Eng. it’ll take a team of horses to get me back. Mind you Eng. in itself is O.K. but this atmosphere – No thanks! I’ve had a miserable cold for over a week now + it doesn’t seem to be getting much better.

“the boys were glad to get out of the rain”

We’ve just got in from a scheme yesterday. It only lasted three days this time. By the way I slept under Anthony Eden’s roof, if you please! No I can’t give you The dope on Turkey + such as “Tony” was up in London. However Winston + he Were coming out to-day but do [sic] to arrangements beyond my control I had to take my leave before their arrival. We were holding a position which extended past the Eden home and as a consequence we were offered the use of the stable for the men to sleep in. There weren’t any horses and the place was spotless + full of hay so you can bet the boys were glad to get out of the rain. The Off. Sgt. + I shared a room together. I scored a spring bed. I wish Mr. Eden had been out There as we would have had a chance to meet him. However you may be sure I asked the help all the necessary questions. Next stop Buckingham Palace.

I received your letter O.K. and certainly am pleased that you are sending me a watch. I can’t make out why you mention a fountain pen as I have one already. I not only brought one with me but I found a good one over here. The maple syrup will be great.

“Don’t forget to have a Christmas tree this year”

Well Christmas will soon be with us once more[.] I sure wish I could be home to share it with you. Don’t forget to have a Christmas tree this year And we’ll all be there in our thoughts on Christmas morning you can bet. If I could be home I’d nail a wash tub to the mantel with a six inch spike and ask Santa to fill it full of roast beef and sirloin steaks. I suppose you’ll have a turkey this year. I’m getting 9 days leave on the 20th + still be spending at the Woods’. They have been fattening half a dozen chickens up for the occasion. I can taste them now. Well, Mother I guess that’s almost the news for now. Don’t forget to drink our health on Christmas. In closing I wish yourself Dad, Rea + John the very best in the coming year + may God Bless You all.

XXXXX Love Bill

“Your Christmas parcel O.K. it was a dandy”

Cpl Hollinsworth provided his mother with his latest news again on 31 December 1944.

I received Your Christmas parcel O.K. it was a dandy. Thanks a million. I spent Christmas at the Woods’. As a matter of fact I was there for nine days and sure had a swell time. Its pretty hard getting into the groove here at camp again. Reveille comes awfully early in the morning especially after you’ve been having tea in bed every morning at 10 o’clock. Oh me! I wish the war was fought on leave.

“I wouldn’t mind Sgts. stripes as it means a lot less work”

I’m going to C.R.I.U. on Monday to instruct our reinforcements. Personally I don’t fancy the job much but as the order came from B.H.Q. even the Major can’t get it changed. Anyhow he says it may mean a promotion. (May is right) However I wouldn’t mind Sgts. stripes as it means a lot less work. As things Stand at present L/Cpls. + Cpls. haven’t any chance of promotion within the Batt. As we have to absorb so many Sgts. From holding units before our Reg. can make promotions. You should see some of the Sgts. we get. All they know is what they learnt at Basic training centres in Can. and as a result the Cpls. have to do their job for them until we can send them back. Some system.

“went to see a couple of plays during my leave’

I went to see a couple of plays during my leave. “Dancing Years” which has been playing two years in London is really worth while seeing. The costumes and scenery are beautiful. Have you seen “For Whom the Bell Tolls” yet[?] It certainly is a good picture. I missed Erving [Irving] Berlin’s “This is the Army” as it left London just before my leave. It was a great stage show and I was disappointed not getting to see it. Its funny in London as far as shows go. You have to book for seats ahead if you want to see one. Believe it or not “Gone with the Wind” has been playing at one theatre for 4 yrs. + you have a devil of a time booking seats for it even now.

We gave a Christmas party at the Castle for the kids in the vicinity. We entertained about 56 of them. One of our transport drivers who is a little on the stout scale played Santa Claus. The boys had been putting candy bars from parcels from home in a big box so we had plenty to go around. They tell me it was quite a success. The boys had a real good Christmas dinner of turkey + pork + all the beer they wanted. I’m going to try to get off duty to-night so I can celebrate New Years Eve in the proper manner. Well, Mom, I guess that’s about all for now. I hope everybody is well at home. Thank Rea for the Cigs I sure needed them. Best all in the New Year.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Love Bill

“Seems a little dour without much animation or sparkle”

As Cpl Hollinsworth mentioned to his mother, the unit sent him to #4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit “on rotation” in January 1944. He was returned to the unit because he “claims he has no interest in being here and wants to get back to field.” On 19 January 1944, an army examiner interviewed Cpl Hollinsworth; again, it was a standard procedure for all Argylls considered for action.

Stability appears adequate, and learning ability is high. Seems a little dour without much animation or sparkle, but looks solid and reliable. Has had good army experience, but has not had much in the way of specialized training. Sent to No. 4 CIRU on rotation from unit on 3 Jan 44, but is being returned to unit after 2 weeks. Claims he has no interest in being there, and wants to get back to field. C.I., however, reports that he was too inexperienced to keep as instructor on rotation.

The interviewer suggested: “Inf – N.C.O[.]” It was noted that he hoped to become a machinist after the war.

“So I guess I’ve made a fairly good mess of things up to now”

Hollinsworth wrote his mother again on 30 January 1944.

How is everything at home these days? I received an airgraph from John the other day + it seems that Rea + John [her husband, John Wilson] have been having a gay old time during his leave. I sure wish I could get home for a weekend. The days when I had a whole tap to myself to wash under, a good bed + have cooked meals seem an awful long time ago. These were the sort of things I took for granted but believe me its those little things that count in life. All I ask after this war is over is the chance to make a decent living. At what, I haven’t the slightest idea. I’ll be 28 this 11th of Feb. So I guess I’ve made a fairly good mess of things up to now. However I still like hunting + fishing, a good book, good friends + animals so guess I’m not so bad off after all if I don’t turn out to be a roaring success or a millionaire.

“they need is a good dose of their own medicine”

We had fronts seats at the castle the other night to a large scale air raid. I was sitting up in my room on the third floor when the first bomb fell. Boy! I thought the roof was going up for sure. I was downstairs outside to have a look in nothing flat. It was a great sight. The Jerries were dropping parachutes flares to light up the target (I haven’t the slightest idea what they could have been after) and the boys were trying to box them in the search lights. It was quite exciting when they got a Jerry boxed + then start throwing shells at him. I was right in form as I got so wound up in watching the show that I walked off the terrace wall. Its an 8 foot drop but I took a header into the shrubbery so I didn’t get hurt. Everybody had a good laugh including myself. Jerry doesn’t stick his nose across the channel very often these days as he usually gets a sound drubbing for his pains. Our air force are certainly giving them an awful pounding judging by the number of bombers we see flying for every territory every day. They asked for it so let them take it is my motto. These people that go around saying, “The poor Germans, it isn’t their fault they were led into it,” give me a pain. You don’t see any of those poor Germans having any scruples about taking the Stuff that were looted out of the conquered countries etc. A good German is a dead German is a motto that holds good as far as I’m concerned. What they need is a good dose of their own medicine and I wouldn’t mind the privilege of prescribing a little of it.

“My goodness + My God!”

Incidentally I told you I received my parcel + cheque in my last letter which you should have by this time. I’m going up to London to-morrow to see the Woods for the day. The training [h]as been fairly strenuous latterly although we haven’t been out on any schemes, Thank the Lord. Oh yes! I forgot to tell you I got out of C.I.R.U. + back to the Reg. I’d have probably got Sgt. stripes if I’d have stayed but the place was strictly phoney + anyway who wants to teach a bunch of Zombies. Did you hear about the chap who went in to buy a brassier [sic] for his girl for Christmas[?] Owing to women being called up over here for service there was a category man behind the counter. He asked the chap what size he wanted. What sizes do they come in was the reply. “Well, replied the salesman, “we have fives sizes – small, medium, large, My goodness + My God!”

Give my love to all at home. God bless you all. XXXXXXX Bill

It is difficult, perhaps foolish, to speculate too much – if at all – based on incomplete documentation. There is nothing in Hollinsworth’s letters to suggest dourness or lack of sparkle. He held the instructional position at 4 CIRU in disdain because he considered it “phoney” and he had no use for so-called Zombies. There may have been some degree of self-reflection over the last months of 1943 and the first month of 1944. On 19 January 1944, the same day as his army interview, Hollinsworth changed his will, giving his mother “all my estate.” He was still married. When he joined in 1940, he had listed his father as his immediate next of kin, and then amended his form on 23 September 1941 to reflect the fact of his marriage and his wife was now his immediate next of kin. There was no provision to assign her a part of his pay. Other military forms list her as immediate next of kin through to 1947, but in mid-January 1944 Hollinsworth decided to leave everything to his mother. None of his letters mention his marriage or his wife. With his 28th birthday on the horizon in February, he observed, “I guess I’ve made a fairly good mess of things up to now.” Was this a reference to his marriage? It is a possibility.

Hollinsworth received “48 hrs plus 7 days priv leave” on 11 March. The early months of 1944 were marked by training in Scotland for two weeks in February, more equipment, work on the ranges, route marches, and fewer exercises. Cpl Hollinsworth embarked for France on 21 July and disembarked there two days later. Bill Hollinsworth went into action with D Company – from the early engagements to Hill 195, Igoville, and Hill 95. The biographies of Ptes Ira Hedman, Jamie MacRae, Joe Bearss, and ACpl Coningsby Gooderham provide context for the battalion’s activities during this period.

There are two compelling elements to the Argylls’ first six weeks in action. The character of the battalion as it faced the inscrutable face of battle is the first element and is manifest in dramatic fashion at Hill 195 (see Lt Milt Boyd and Lt-Col Dave Stewart). Battle is Janus-faced: one side inscrutable, the other monstrous – the face of death and wounding. From 29 July to 7 September, the battalion lost 84 KIA, including 1 major, 6 lieutenants, and 6 NCOs; the wounded numbered 229, including 3 majors, 2 captains, 7 lieutenants, and 11 NCOs; the POWs were 20, including 1 major, 1 captain, and 3 NCOs. The total was 333 struck off strength between 29 July and 7 September! The battalion’s establishment on 26 July was just over 800; its fighting strength 400 to 500. B and C companies sustained such heavy losses that they were amalgamated into one company following their action at St Lambert (see A/Sgt Cecil Fisher, Pte Ira Hedman, and Pte “Pop” Burrill).

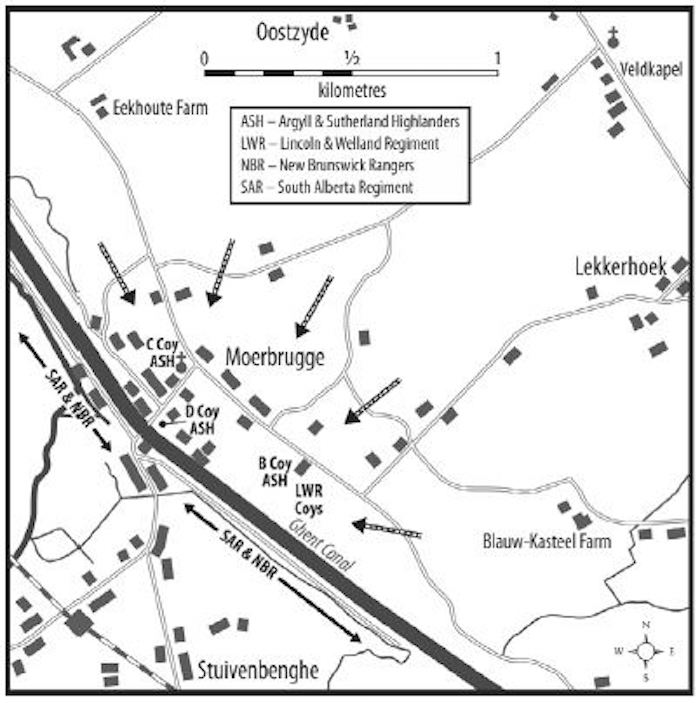

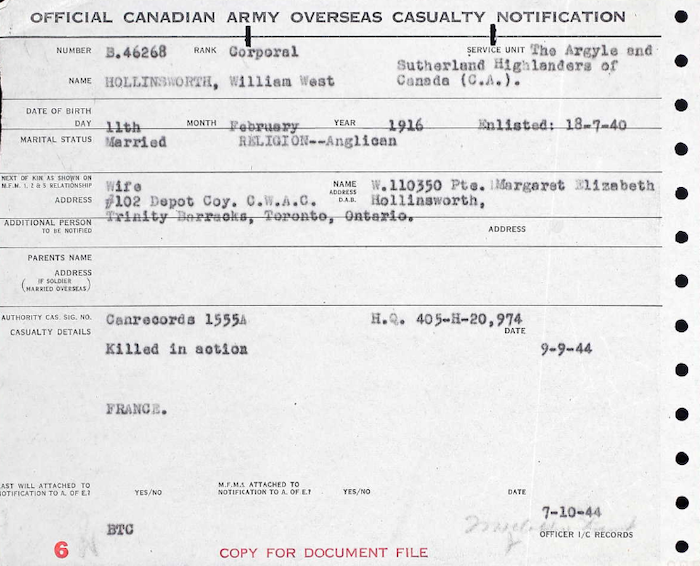

Cpl Hollinsworth met his fate at Moerbrugge, Belgium; the first stages of the battle unfold in the biographies of Ptes Johnny Sawyer and Adolph O’Back. Bill Hollinsworth was killed there on 9 September 1944. He was killed in action with D Company during the furious fighting at Moerbrugge.

“I remember finding Fish Hollinsworth dead”

Pte Mac MacKenzie, 18 Platoon, D Company, never forgot him:

I remember finding Fish Hollinsworth dead. A look of something – it was a look of horror and a look of surprise – on his face. He must have seen the guy [who shot him] ’cause he never suffered; there was a hole right through his bloody neck and he never even knew. “Bill Hollinsworth, he was killed…. And that, really, really upset me.”

Hollinsworth’s death shook CSM Wilf Stone a former comrade in D Company:

This fellow who introduced me to my wife, Bill Hollinsworth, he was killed…. And that, really, really upset me. I guess maybe that was the worst case of being upset that I had … he used to be able to recite Robert W. Service [the poet]…. And I can remember Bill, he’d had a few drinks and was sitting in the barracks in Newcastle [Jamaica], and he had his feet up, sitting in his underwear, and he just went on for hours reciting the poetry of Robert W. Service. It was great.

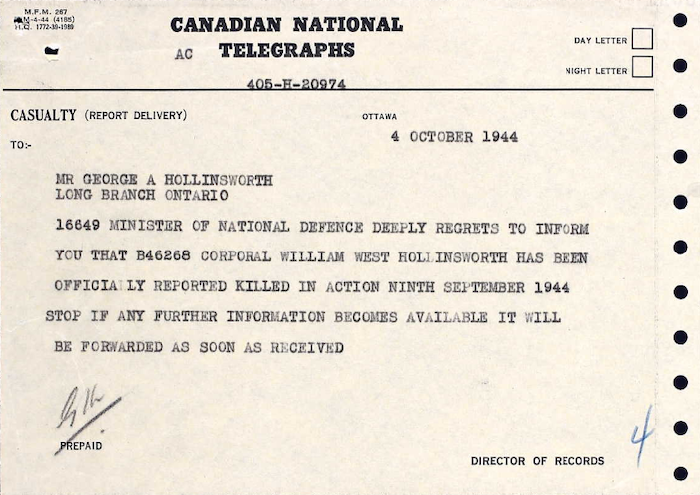

Padre Charlie Maclean buried Cpl Hollinsworth two days later, on the 11th, in a temporary grave in Moerbrugge on “L hand side of road St. Georges [church]. There was a small burial party, a reverent but short service, and a regimental piper playing the Argylls’ wartime lament, ”Flowers of the Forest.” Telegrams and letters were sent to his next of kin – his wife, Peggy Hollinsworth. The army estates branch handled his will with his father.

“Marriage Cert.”

In terms of personal effects, Cpl Hollinsworth left an Argyll Glengarry, a New Testament, an Argyll cap badge, a flashlight, a Bible, a wallet, photos, and a “Marriage Cert.” Bill Hollinsworth had, according to the estate forms filled out by his father, no property, no assets, no bank account, and no debts. As for insurance, he had “a [$]2500 policy but allowed it to lapse on account of War clause.” The forms listed relatives beginning with the “Widow of the Deceased.” Bill’s father filled in her name – Margaret Hollinsworth – and gave her age as “24?” As for her address, he wrote “unknown to us.” Peggy’s Memorial Cross was returned; she moved to Port Arthur, Ont., after the war and could not be located.

“the girl that came to the door”

Cpl Hollinsworth’s death devastated his family; they had lost a second son. Rea Wilson’s daughter, Penny Brooks, heard about “a child” about 1958. She overheard a conversation in her Grandmother Nina’s home between her grandmother and Anne Holiday, a close friend of Penny’s mother. They were talking about “the girl that came to the door.” At some point either after Bill’s death or after the war, Peggy Hollinsworth visited Bill’s home in Long Branch. Nina Hollinsworth turned her away. Penny recalls her grandmother dismissing “the girl’s” conversation as “poppycock.” Penny was “a child. I didn’t ask questions.” Her mother, Rea, confirmed the story of the marriage and the child, but nothing more.

Nina Hollinsworth’s home was “strange” and “odd” after the war. The family had lost two sons and Bill’s brother Rex “didn’t return the same man.” “My mother adored Bill, shared books with Bill, and poetry.” They were “into pretty heavy poetry.” Rex Hollinsworth “never talked about the war or his brothers.” He did tell Penny’s brother, John Wilson, that Bill had married a second cousin and they had a child. Rea “talked but not in depth. She would say Bill loved that or Bill liked this, mostly about books.” Bill and Rea “lived in a comfortable home, well cared for, and [they were] not forced to work, [it was] a wonderful opportunity to learn, books [were] always available to them.” The family attended church “regularly” and the family “had a good healthy respect for religion.” They “believed in the Ten Commandments and [to] live your life according to them.”

“the grief, maybe, just never left”

Nina told her granddaughter once that “we all have the same colour of blood, but don’t ever marry a Catholic.” Jack Hollinsworth was killed just before Christmas in 1943. His mother “kept it to herself until after Christmas.” She was a “very strong woman, very close to her daughter [Rea].” She talked about her sons “in a factual way, but not emotional; her sadness was personal and private.” There were no “pictures on display.” Rea “handled it in the same way, just factual.” She thought of Bill “as a sweet caring individual and others were drawn to him.” The family’s “wartime loss was talked about so little, the grief, maybe, just never left.”

Harry Hollinsworth was Peggy Hollinsworth’s (née Hollinsworth) nephew. Their side of the family was “military.” She had moved to Port Arthur by 1947 and was remarried in 1951, to Jack Tapp; they had no children and lived on a rural property, where she cared for animals, both domestic and wild. Harry “knew Peggy well.” She “talked about her time in the army; she loved it.” She was “very outspoken” and “very crusty.” She was “proud of the army and proud of their heritage.” She separated from her second husband in the 1980s: “I have no idea what happened” but they became “estranged” and she “became reclusive.” She “never talked about him [Bill].” Harry found out that his aunt had married a cousin in the 1970s: it was “a no-no.” The family never discussed it.

Penny Donovan (née Hollinsworth) is Harry’s brother and Peggy’s niece. After Peggy moved back to Fort William, she lived behind her parents on a rural property, where, as her brother noted, she cared for wild and domestic animals and birds. She saw Peggy “often” and remembers her as a “vibrant” woman within the community, renowned for her concern for animals. She had a radio show in the 1960s and discussed birds and animals. Neither of her parents ever discussed Peggy’s first husband or child. “They didn’t talk about such things.” Peggy’s obituary lists her medals, including her Silver Cross medal. She served in the local militia from 1951 to 1972, was married in uniform, and rose to the rank of sergeant. She was “an avid lover of wild life and was affectionately known as ‘the Bird Lady.’” Her home was a “wild life sanctuary.” After her separation from Jack Tapp, she moved “into a lower income apartment.” She had “little money” and was unwell in her last years.

“Peggy was predeceased by a son, William Athelston, in infancy”

Peggy and Bill Hollinsworth were remembered by families, but their life together was hidden and unspoken to succeeding generations. The decades of silence, including Peggy’s, from 1944 to 1994 (Peggy’s death) were shattered by the content of her obituary. No one knows who wrote it, but it was someone who knew her intimately and knew everything about her life. Towards the end, it reads:

Peggy was predeceased by a son, William Athelston, in infancy, first husband, Sgt [sic] William Hollinsworth, in action in 1944 …

With respect – Ancaster Minor Hockey League.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Cpl Hollinsworth’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

William West “Fish” Hollinsworth.

William Hollinsworth as an infant.

Hatti and Nina are in the middle. Bill and Rea are the children in front.

Front row: George Athelston Hollinsworth (Bill’s father), Nina Hollinsworth (Bill’s mother), Grandma Crawford (Bill’s maternal grandmother).

Back row: Hatti Armstrong (Bill’s maternal aunt), Jack Armstrong (Bill’s uncle).

Young Bill loved fishing, which earned him the nickname “Fish.”

Bill and his big catch of the day.

Bill with his catch.

Bill’s sister, Rea Emily Hollinsworth.

Above and below: Bill with his sister, Rea. According to Rea’s sister, she adored him.

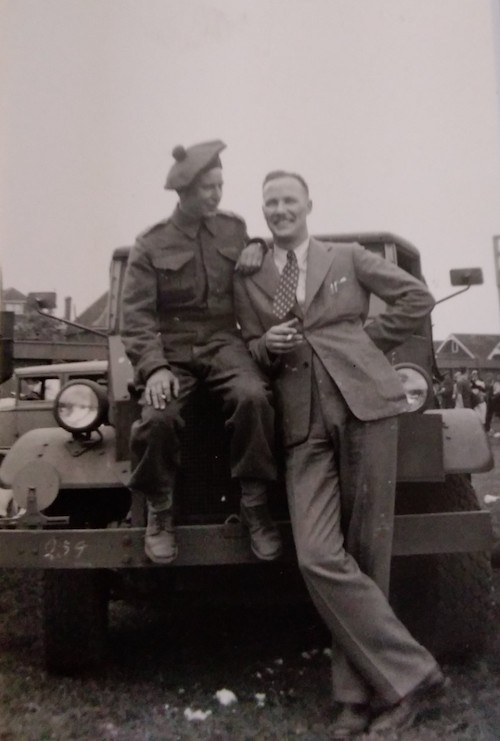

Bill with his father, George.

Bill Hollinsworth with his brother-in-law John Wilson, Rea’s husband.

Sisters Hatti (left) and Nina.

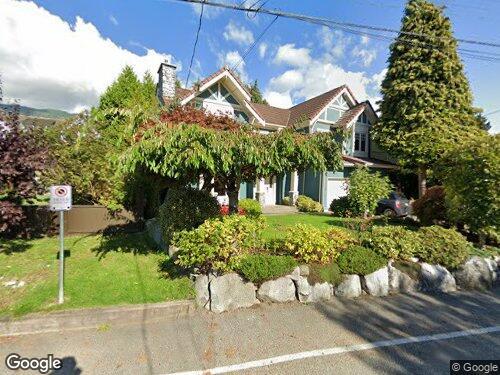

275 Needham Street, Nanaimo (modern view).

2379 Haywood Avenue Vancouver (modern view).

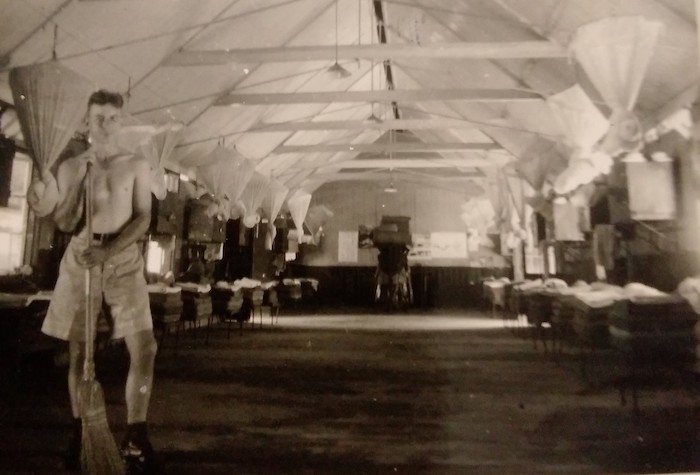

Bill Hollinsworth at the barracks at Up Park Camp, Jamaica.

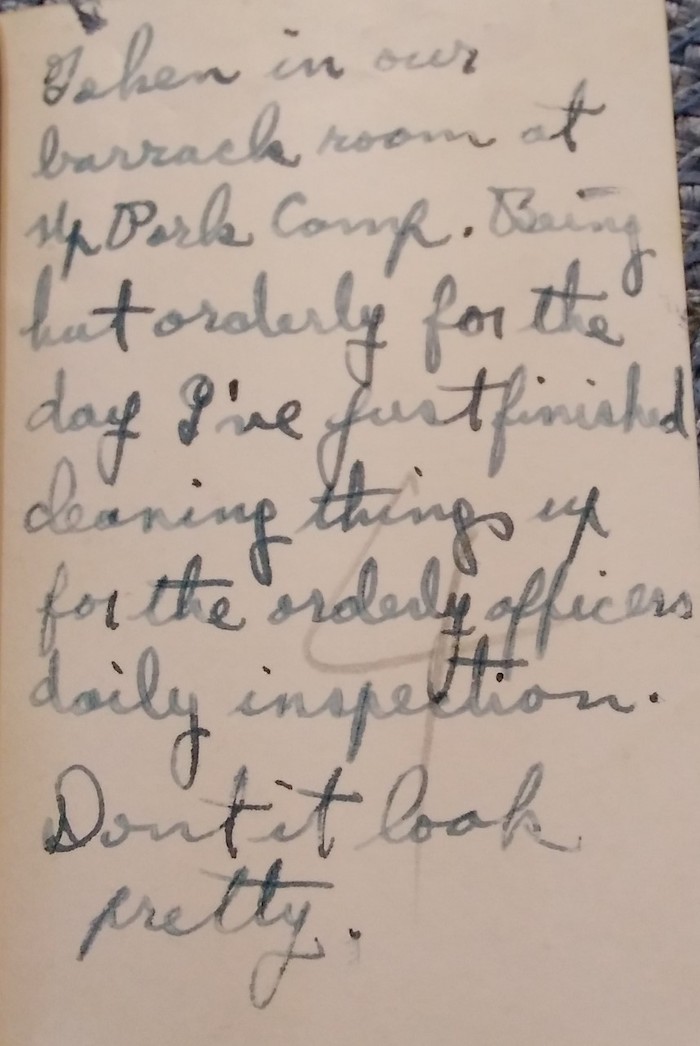

Note on the back of the picture of barracks at Up Park Camp.

Too tired to read.

RMS Lady Drake, circa 1930s.

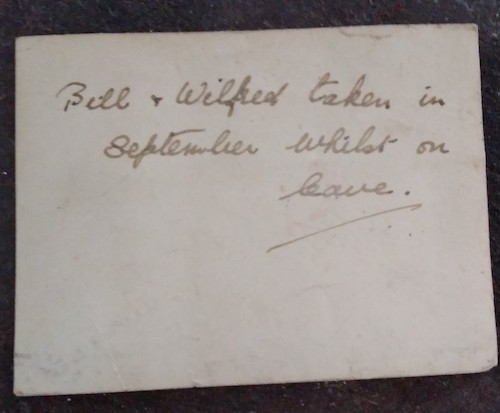

Bill Hollinsworth and Wilfred on leave.

Note on the back of the photo.

Member of the CWAC, Trinity Barracks, circa 1945.

Pill box, Old Hunstanton.

Ghent Canal, Moerbrugge. CSM George Mitchell of C Coy wrote on the back: “The first problem was to secure a crossing.”

CSM George Mitchell wrote on the back of this picture: “A view of the side of the canal we had to cross to.”

Sherman tank, Moerbrugge.

Moerbrugge, with the spire of St George’s Church.

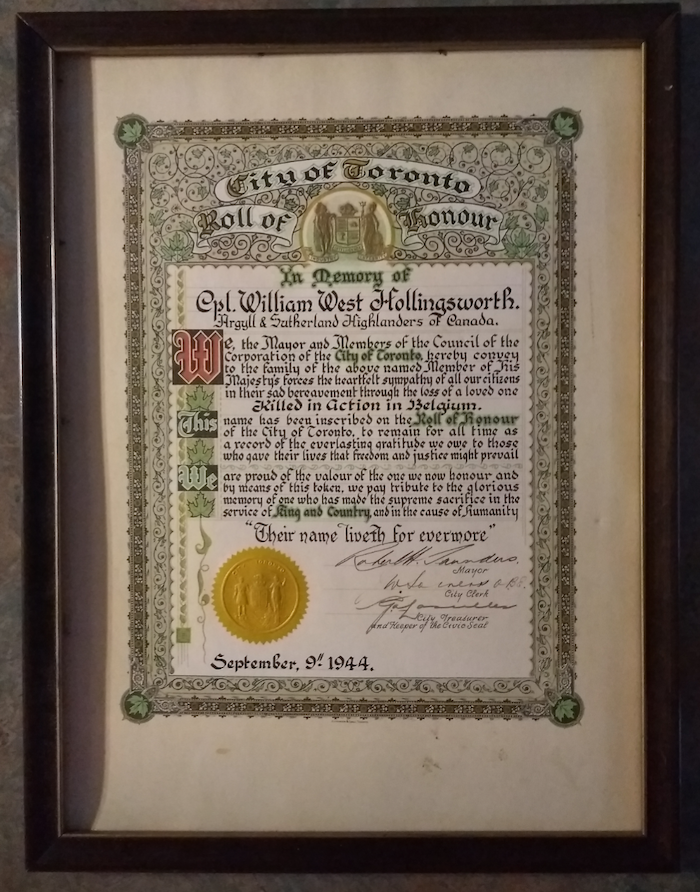

City of Toronto roll of honour.

Peggy Hollinsworth, Teresa Evans Hollinsworth, and Percy Sandham Hollinsworth at Peggy’s wedding to Jack Tapp, 1951.

Peggy Hollinsworth and an unknown soldier at Peggy’s 1951 wedding.

Bill’s oldest brother, Jack Athelston Hollinsworth.

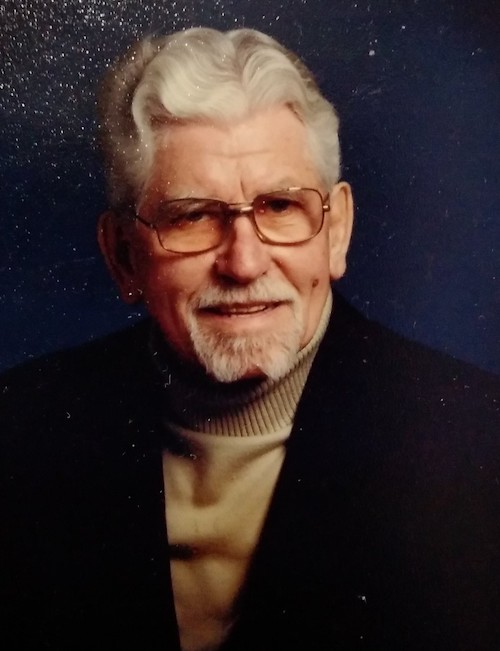

Bill’s brother Rex Crawford Hollinsworth in later years.

Teresa Hollinsworth Evans.