Message from the Commanding Officer & Honorary Colonel

1 November 2022

Dear fellow Argyll,

Earlier this year, we sent birthday greetings to Col Alan Earp, OC, on his 97th. We had hoped to offer similar greetings to another Second War veteran, Sgt James S. Scharf, who celebrated his 100th birthday on 3 May this year. Unfortunately, Sgt Scharf died on 30 May, before it could be organized.

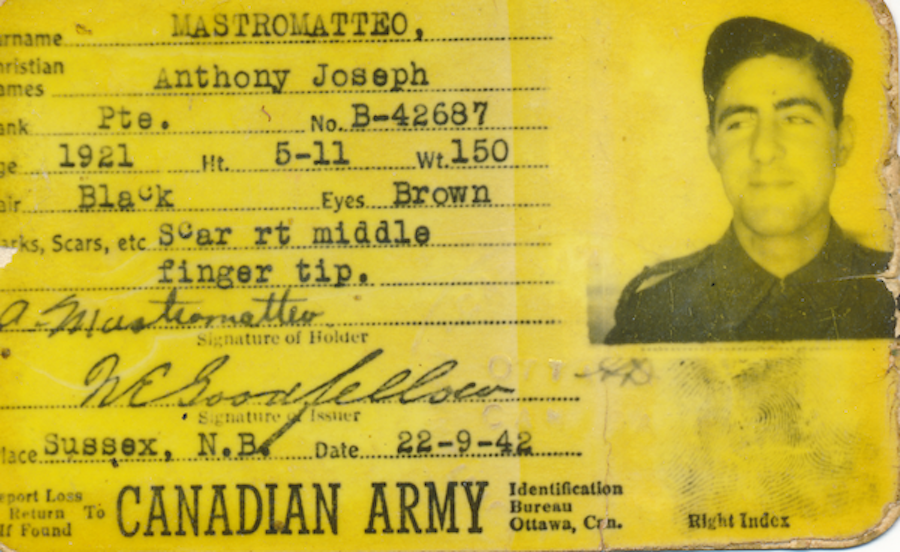

Today, we – belatedly – mark the 101st birthday of Pte Anthony (Tony) J. Mastromatteo, which was celebrated earlier this year. He served in action with the 1st Battalion during the Second War and was with the Scout Platoon. He was wounded on 29 October 1944, one of 39 casualties that day (10 killed; 29 wounded).

Pte Mastromatteo, on behalf of the serving battalion and the Regimental family, we offer you our best wishes for your birthday. Today, we are all Scouts and we salute your service. We have asked the Regimental historian to provide some perspective on your life and wartime service.

Albainn Gu Brath,

Carlo C. Tittarelli, CD

Lieutenant-Colonel

Commanding Officer

Glenn Gibson

Honorary Colonel

Message from the Regimental Historian

I have known of Pte Tony Mastromatteo since the 1980s and the beginnings of the Black Yesterdays project. Gord Boulton and other Scouts urged us to interview him. Our students contacted him, but he decided against it in spite of the urgings of his wife, Mary, and his daughter, Laura LeMesurier. Tony, like most Argyll veterans, never spoke to his family about the war except in the broadest terms. As Laura said, “Not at all – Mom begged him to be interviewed for the book,” but without success. I offer my thanks to Tony for agreeing to an interview, to Laura for her assistance in gathering images and arranging the interview, and to LCmdr Michael Chorney, CD, for making available the work of the family historians.

Born in Italy

Ernesto Mastromattei was Tony Mastromatteo’s uncle. In November 1917, Ernesto Mastromattei (how he signed his name on various forms in his personnel file) was drafted for service in the First World War. He provided the date of his birth (7 February 1892) and his place of birth, Monte Santo Giovannie, Campano, Colli. He assigned pay of $10 monthly to his mother, Stella Mastromattei.

The family historians of the Mastromatteo/Mastromattei family describe the “small farm, with olive trees” in the “little village named Colli.” It is “near the town of Ceprano … in the region called Lazio, which extends south of Rome almost to Naples…. The farm produced enough for the family needs but it was not particularly profitable. The two Mastromattei brothers, who worked on the family farm, in about 1905-1906, began to discuss leaving the farm to make their life and fortune in America.”

Emigration

Not surprisingly, the story of the Mastromatteo family in Canada has its genesis in emigration. Luigi Mastromatteo was born in Colli in about 1883. There were three main waves of Italian immigration to Canada. The first lasted from 1870 to 1914, when it was interrupted by the First World War. Between 1900 and 1914, 119,700 Italians immigrated to Canada; most (over 75%) were from Italy’s southern regions. Most were young, single males who entered Canada from the United States. By 1911, there were more than 4,600 in Toronto.

The Mastromatteo family was part of the first wave. According to family lore, Luigi (1883-1953) and his younger brother, Ernesto, considered leaving the family’s small olive farm. Their mother, Stella, married three times. Her third marriage was to Bernardo Mastromattei, and they had three children: Luigi (born 1 May 1883, Evangelista born circa 1886, and Ernesto born 7 February 1892. Widowed for a third time, Stella died in the mid-1930s. In 1905, Luigi landed in New York, with Montreal as his destination and hope of work on the Canadian Pacific Railway. The padrone system, which was used to recruit young Italian workers, was still operative in Montreal, albeit on its last legs, and it is possible that Luigi was lured by it.

Luigi married Maria Fiori (Fiore) (d. 1954) in Italy on 21 January 1908. According to the family’s historians, the “story goes that Maria’s branch of the Fiore family did not like the Mastromattei branch, so Maria eloped and married Luigi on his visit to Italy. She had one infant in Italy who died with convulsions.” In 1909, Luigi was living in Salem, Massachusetts, presumably with Maria. On 24 July 1909, he tried to enter Canada and make his way to Montreal. Because he had “No money,” he was “REJECTED,” and turned back. Finally, in February 1911, Luigi and Maria arrived at Montreal from Boston. He is listed as a “Laborer” with no relatives in Canada, and unable to read or write. The same was true of Maria.

Life in Toronto

By 1914, Luigi is listed in the Toronto city directory as a labourer living at 20 Portland Street. Their first child, Angelina, was born there on 26 October 1914. Ernesto was living at 522 Front Street West in 1917 and working as a car [railway car] repairer. At enlistment, he was, not surprisingly, attached to the Canadian Overseas Railway Construction Company. He served in France and Belgium and was demobilized in Toronto in 1919.

By 1920 the Mastromatteos are listed at 9 Draper Street, a row of delightful Second Empire houses built in 1882. The 1921 census provides further detail. The family rented ($27 monthly) this semi-detached house with brick veneer and six rooms to accommodate three adults and six young children. Luigi was a “car repairer” on the Grand Trunk Railway and earned $1,680 annually, as did his brother Ernesto (then 29), who lived with them; the brothers had identical occupations and wages. The family had grown. In addition to Angelina, there was Bernardo (named, presumably, after Luigi’s father), who was born in 1916, Theresa Rose in 1917, and Tony, the youngest, in 1921. They were, as Tony puts it, “a religious family” who attended St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church at the intersection of Bathurst and Adelaide streets. There, the children attended the separate school. Eventually, there would be 12 children in all – six girls and six boys. Maria, Tony remembers, spoke English but could not read it. He did not speak it, but did understand it. He reached Grade 10 at St Mary’s Separate School before going to work. Tony “played ball, liked sports.”

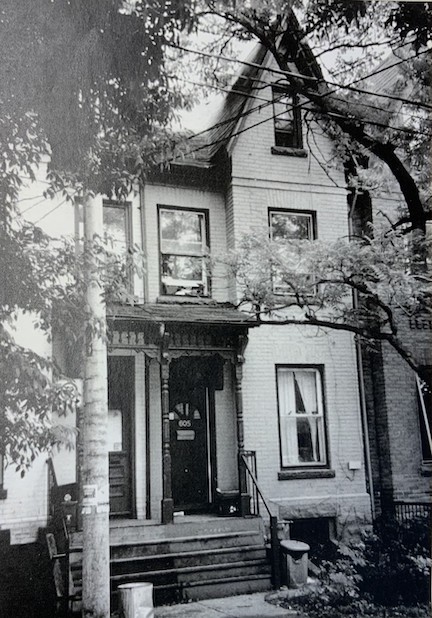

The family historians provide some insight into the contours of their lives. “Luigi largely made his living by buying and selling fruit, which he peddled on a pushcart through the streets of Toronto. He had a room in his basement at 605 Wellington Street, where fruit was ripened with ethylene gas.” When Luigi bought his home at 605 Wellington Street West, “their [Luigi’s and Ernesto’s] families lived together in the same house until the size of their families made this difficult.” Thereafter, they lived “within walking distance of each other.”

“The two families always spent Christmas together at 605, playing tombola (a game similar to bingo), sett’e mezzo (a game similar to blackjack), scopa, and other games; eating pizza frittelle, bow ties (crustoli), roast chicken or pork, pasta, insalata, and fruit. The men played briscola and padrone e sotto (boss) and drank lots of wine. In the game of padrone e sotto, the winners controlled who would be able to drink wine, and at the end of the evening you could tell who the best players were. The women prepared endless food in the kitchen.”

The outbreak of war in September 1939 altered the path of Tony Mastromatteo’s life.

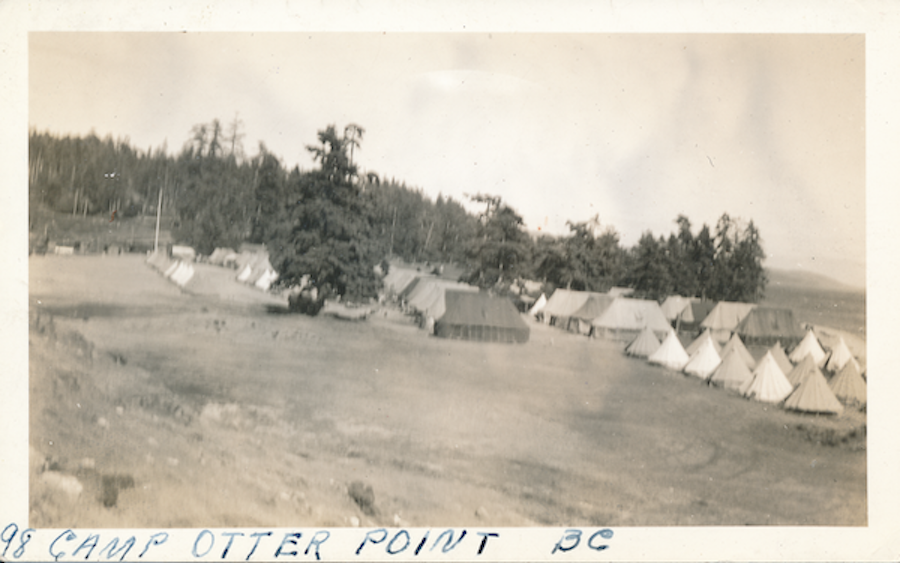

“I had no experience but it was war” – 1940

Tony enlisted in 1940 at Hamilton with the Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles of Canada. “I joined because I thought it was my duty to do so…. I was proud to be a soldier in the Canadian army – good stuff!… I wanted to go to Italy, but never got a chance…. I had no experience but it was war – all good stuff.” He was with “the Duffs” in Nanaimo and played in the bugle band. The war had a romantic dimension for young Pte Mastromatteo. While stationed in Nanaimo, he met Mary Pollock (d. 2017) who, as daughter Laura LeMesurier tells it, “was living there working as a soda jerk and Tony and 2 of his buddies walked in to get floats…. The rest,” as she says, “is history.” The Duffs did not go overseas. The year 1943 proved to be momentous for him. In February, Mary and Tony were married at St Mary’s; the Argylls returned from Jamaica in late May 1943, and Tony was taken on strength at Camp Niagara, probably in early June.

The Argylls, 13 Platoon, C Company, 1943 – “a good battalion, [they] knew their stuff”

To Pte Mastromatteo, it was “a good battalion, [they] knew their stuff, did everything proper, I can’t complain.” He joined a rifle company, C Company (see Pte Percy Samuel Hindle) and was in 13 Platoon. The battalion entrained for Sussex, New Brunswick, on 9 July, boarded the Queen Elizabeth on 21 July, and arrived in Gourick, Scotland, on the 27th. The following day the Argylls were on trains again, crossing the border to England during the night of the 28th. The train “arrived at Camberley at 1215 hours. The troops detrained and marched to separate billets – large unoccupied homes.” There were battalion parades, church parades, route marches, passes, medical inspections, leaves, new equipment, and a new training syllabus of refresher courses in every aspect of infantry life. The Argylls were readying themselves for the forthcoming invasion of Europe, and preparation for battle dominated the coming months.

On 1 October 1943, with the new CO, Lt-Col J. David Stewart, who “marched with the men,” the battalion moved to Riddlesworth Camp. “A regimental piper preceded each company as an aid to flagging feet, but blisters and blasphemy were common.” There were more reinforcements on the first day at (as Pte John Booth expressed it) “the dirtiest camp we ever moved into and it took plenty of work to make it fit to live in.” On 2 October another group of reinforcements arrived, including Pte Donald Douglas MacKeracher and Pte Welby Lloyd Patterson, a Tuscarora from Six Nations; both were posted to C, Tony’s company. Capt Bob Paterson was a first-rate second-in-command; George Mitchell was the formidable company sergeant-major; and Lt Gord Sloane (KIA 5 August 1944) and Lt Alf Henderson (KIA 27 August 1944) were good platoon commanders.

Training in the UK — “weather was terrible”

Few of Pte Mastromatteo’s letters home have survived. The letters and reminiscences of others furnish a sense of existence in the company. Pte Jamie MacRae was another of the new reinforcements posted to C. He wrote to his parents that “the spirit of cooperation and friendliness is much more apparent than in any camp I have been in yet which is a pleasant change.” On 10 October, he had “been pretty busy the past week and the training here is plenty tough. We are in the field two days and in the camp one … The fellows here are all nice to be with. They have been together long enough that petty jealousies are not apparent and all are more helpful to the new men.” Seven days later he commented that “Our training is interesting, tough and thorough … discipline is rigid.” On the 19th, the battalion was on a major exercise: “Grizzly II — Battle manoeuvre in conjunction with tanks is the order of the day with all rifle companies engaged.” The “weather was terrible” and the troops were “wet and miserable.” Capt Paterson, the 2ic, described it as “awful, absolutely awful … it was all messed up. We had no fires, nothing … and everything went wrong.”

“Yes the sooner this thing is over the sooner I’ll be coming home”

One of Tony’s letters from the training period in the fall of 1943 has survived. It suggests the phlegmatic, cheery, easygoing approach to life that defines him. Although he did not return home until December 1945, he writes as if that eventuality was imminent. The war had a reality in the United Kingdom that contrasted with Canada, and he took notice. As for the apparent cultural and social differences, they amused him.

On the 19th, Tony wrote to his brother, “Ernie & everyone.” He had but “a few minutes to write & say that I’ve arrived here safely.” He was “surprised to see so many places blacked out over here” and, as for driving “on the left side of the street – it looks awful.” The “double decker buses are really a laugh … you’d swear that it was going to turn over [on a turn] but nothing like that happens.” As for the money, it “is funny.” “As for sweets you must have coupons & we don’t get them. The same goes for smokes. What a job we have getting around over here. All we can do to get around is either walk or ride a bicycle or then again ride the train.”

Tony went to London “a while back” and saw “some of the spots like Downing St & Scotland Yard…. I went to Windsor Castle & seen a lot of old things & I mean old. Their [sic] were some tombs of all kinds. I seen King George V’s tomb and beside it is a place for Queen Mary…. At present I’m on the Channel & what a sight to see the boys doing a job…. I suppose the next thing I know is that I’ll be on my way home again. Yes the sooner this thing is over the sooner I’ll be coming home. Things do look good don’t they. At present I’m in a house with 14 rooms and what a house. In every room is a buzzer for ringing for the maid or anyone you might want but remember theirs [sic] none of that over here anymore.”

“All the girls are either on war work or in uniforms. This place is really out towards the war’s end.”

“Well so long for now – as the English say Cheerio old chaps.”

“the normal military groove”

After another large exercise at the start of November, the Argylls moved – “Reveille at 0430 hours” – on 6 November to new quarters in Uckfield, Sussex. The various companies were “quartered in large manor houses … The Cedars (‘C’), – all within 5 miles of Uckfield.” The companies concentrated “chiefly on conditioning work – including speed marches” as “life” settled “down into the normal military groove.” There were more new faces, plenty of time on the rifle ranges, more field exercises, new weapons, and Christmas celebrations with parties for local children, Christmas food, and, as reported by Pte MacRae, “every man in our coy had at least one parcel from home and some got several.” At Uckfield, Pte Mastromatteo did find time for some profitable relaxation. He “made a little bit of gambling money, playing cards and dice, and sent it home” to Mary. There is also a story about a certain package. During the course of the interview, Laura raised the subject. But, in Tony’s words, it is “a naughty story” and will remain untold.

While in Uckfield, Tony “got word … that I was the proud father of a baby son, Carmen, a nice little son.” Tony “wrote quite often and Mother liked it although she could not read it. Mary wrote, “but after the unit went into action,” Tony did “not get letters too often because we were all over the place.”

The Scout Platoon, March 1944 – “a very good platoon, we did very well”

There was a new development in the battalion in March 1944. LCol Dave Stewart gave command of the newly formed Scout Platoon on 8 March to Lt Lloyd Johnston because, as Stewart put it, “he suited the job.” Lt Alan Earp (now Col Earp) commanded the Pioneer Platoon from November 1944 until he was wounded on 14 April 1945. He, along with Pte Mastromatteo, is one of the two surviving Argyll veterans. Alan writes: “The Scouts were as close to an elite platoon as the Argylls had and, I suspect, would have peaked under Johnston, whose grave I remember visiting.” Lt Earp muses that “although they included crack shots the Scouts were much more than snipers: interestingly, at least to me, they do not seem to have suffered from a ‘sniper syndrome’ of coming to hate their job, viz Cec French [killed at Friesoythe on 14 April 1945) and, I believe, others everywhere I suspect it was that their tasks were so much more varied than the monotony of picking off men from you own lonely perch.” The Scouts certainly were crack shots and had sniper training. In action, they could be used as a full platoon as they were at Hill 195 on 9/10 August, Moerbrugge on 8 to 10 September, and Watervliet on 14 October. More often, they were used in small groups, often two or three, for reconnaissance, or singly to guide companies or platoons to their positions.

Capt Lloyd Johnston: “tough as nails, well built, proud.”

Command of the Scouts was, as Lt Bob Pogue (Johnston’s successor) recalled, “a terrible job” requiring a special type of soldier, one such as Johnston. Argylls volunteered for this special platoon and were hand-chosen by the tough, popular, and highly capable Johnston. Tony Mastromatteo was one of Johnston’s chosen. The training was hard and Tony relished it, and his fellow Scouts. It was, he said, “a very good platoon, we did very well.” It was a “lot of fun.” “Lloyd Johnston was a very nice person, well-liked, we got along with him, everything he said was perfect – a good officer, very good – quite an officer.” Pte Mastromatteo also held ASgt Gerald Norman Magee in high regard. He was wounded at Moerbrugge with the Scouts on 8 September and was killed in April 1944. In 1945, Maj Hugh Maclean described Magee as “a brave, cool soldier … from the scout platoon, whose main reliance and stay he had been for months.”

“THE NEWLY ORGANIZED SPECIALIST OR SCOUT PLATOON. COMPRISED OF PICKED MEN”

On 8 March 1944, Lt Boyd wrote in the unit’s war diary:

A source of much interest of late is the newly organized specialist or scout platoon. Comprised of picked men from the different companies … they should prove a valuable addition to the unit. The men will be thoroughly trained in the arts of fieldcraft; have a comprehensive knowledge of enemy weapons and in some instances be bi-lingual.

Scout Platoon. Pte Mastromatteo is in the second row, third from the left.

Lt Lloyd Johnston is in the centre rear (wearing balmoral).

“THEY’RE GOING TO PICK THIRTY GUYS”

Lt Lloyd Johnston, the newly appointed Scout officer, interviewed interested Argylls “in the whole unit.” He picked Pte Mastromatteo as one of “thirty guys” for the new platoon. Cpl Gord Boulton recalled:

“…they said that they were getting a scout platoon together … and they’re… interviewing for it in the whole unit … They’re going to pick thirty guys … and I was tired of being a private, too … I thought, ‘Dammit, I’m gonna go for that,’ you know. So I put in for it and I was interviewed by the officer, [Lt] Lloyd Johnston, who was an unbelievable person, fantastic individual.”

“THE ONLY PLATOON … THAT CAME DIRECTLY UNDER THE CO”

There was, of course, a command structure within the unit and the Scout Officer, especially one such as Capt Lloyd Johnston, was certainly an integral part of it. That said, it was a looser structure. Maj R.D. “Pete” Mackenzie commanded Support Company:

“They [the scouts] were the only platoon organization that came directly under the CO. They were nominally under my command in France, but the jobs they were given either came directly from the CO, or from the CO to me to them.”

“IF YOU’RE NOT AFRAID, THEN YOU’RE NOT WARY. BUT WE WERE …”

Pte Mastromatteo disembarked in France with the Scouts on 22 July 1944. Lt-Col Dave Stewart trusted Johnston and used the Scouts frequently. Cpl Boulton explained:

“… you don’t really know what to expect and you’re still scared. I mean anybody who says they’re not afraid … doesn’t have a brain, you know. You gotta be afraid, or else you wouldn’t be affected. If you’re not afraid, then you’re not wary. But we were …”

Into action – “heavy shelling”

The battalion’s move to the front and to battle was not immediate. The signs of war were everywhere. The sight of the destruction of Caen made a powerful impression. The Argylls and C Company took their first casualties on 29 July. Pte Mastromatteo served in C from June 1943 until March 1944. He knew the men from C who were killed as the battalion inched into action. Death, heat, dust, dysentery, and flies remained forever etched in the memories of survivors. CSM George Mitchell of C Company noted cryptically in his diary: “First casualties – P. Hindle [Percy Samuel Hindle] – McCann [Pte William Daniel McCann]. Coy Despondent – realize that it’s war. Enemy shelling hot and heavy.” A few days later, Pte James Bannatyne, also of C Company, was killed, followed by Pte Joe Carlton at Tilley-la-Campagne on 5 August, along with Lt Gord Sloane, who commanded 14 Platoon which was, as Pte Bill Wolosyn put it, “slaughtered.”

Scout Platoon – France, August 1944. Pte Mastromatteo is standing, fifth from the left.

The Scout Platoon in action – “All my friends, all buddies, good boys – all worked together”

Pte Mastromatteo recalls vividly the “heavy shelling” of those early days in Normandy. On the 5th, the Scouts were in Tilley. The Scouts’ sergeant, Norm Magee, was with Pte Paul “Cosy” Cole – “they were buddies together all the time.” When they were shelled, “Magee flopped on the floor on his belly inside a building [and got] a piece of shrapnel on the ball of his boot but [to Magee’s credit] he didn’t go out.” Tony Mastromatteo has retained his respect for Magee to this day.

Pte Paul Joseph Cole after enlisting in 1943.

The Scouts often worked alone as a platoon or in small groups patrolling. More often than not, they patrolled at night. Pte Mastromatteo remembers a lot of crawling, including up hills and often – and happily – not finding Germans. Later, when the weather turned, he recalls “climbing up a hill, at night, cold and wet [and when they got to the top there], was nothing there.”

Hill 195 9/10 August

The Scouts quickly achieved battalion-level renown, especially after the exploits at Hill 195 on 9-10 August 1944. At Hill 195, the Argylls excelled in the imaginative, unorthodox, daring, and disobedient leadership of Lt-Col Stewart. What made the audacious plan possible? It was a potent combination of Stewart’s initiative and the confidence he instilled in Argylls at all rank levels; the prowess and training of the Scout Platoon; the leadership of officers and NCOs at the company and platoon levels; and the “warrior spirit” of well-trained soldiers confident in their leaders. And Pte Mastromatteo was one of those warriors.

The battalion-scale achievement at Hill 195 has been noted by historians for its singularity within the Normandy campaign. As such, it is worth discussing at some length.

“I TOOK THE SCOUT PLATOON WITH ME AND WE RECONNOITRED THE ROUTE I HAD CHOSEN”

The last-minute Argyll attack occurred against the backdrop of catastrophic failure. On 9 August, a combined force of British Columbia Regiment (BCR) tanks and Algonquin Regiment infantry attacked Hill 195 – “an obvious strongpoint … the highest ground between Caen and Falaise.” The battle group got “off track” and was decimated by the Germans by late afternoon of the 10th. The BCRs lost 47 tanks, 112 men killed and wounded, and 34 POWs; the Algonquins lost 128 killed and wounded and 45 POWs.

Stewart and his battalion received the order to attack at about 2200 hours on the 10th. In Dave Stewart’s words:

“When we received the orders to take ‘Hill 195’ it was late … and two other regiments had tried but were misdirected and got off the track. I mentally wrote the Argylls off as well as myself…. I took the scout platoon with me and we reconnoitred the route I had chosen. On the way back I left members of the scout platoon at strategic points, to guide the Battalion, so I could lead them up to the high ground.”

Stewart’s verve on that fateful night made a lasting impression on Capt Bill Whiteside of the Anti-Tank Platoon:

“…the CO came back [from the reconnaissance with the Scouts] and we had an O Group. And it was at night, and he said, ‘This is what is happening and the first company moves … in twenty minutes…’”

“… THE REGIMENT’S STYLE WAS STEWART’S STYLE …”

In his post-war ruminations, Maj Maclean observed that:

“… the regiment’s style was Stewart’s style … there was a battle to win, or lose, and a certain style to maintain. A manner, if you like, with which to confront the inscrutable face of battle, and endure in spite of it.”

“A NIGHT MOVEMENT WITH SCOUT PLATOON PROVIDING PICKETS”

That style was on stunning display in Stewart’s late-night O group. In his own mind, from the time of the order, he wrote off his battalion. He said once, a “CO to my mind is the most lonesome occupation that could be…. Get a job done; save lives.” That night, he did both and in magnificent fashion. Capt Pete MacKenzie, OC, Support Company was in the O group:

“Dave Stewart was very positive about it. He certainly knew the problems, but he had a very definite plan of a night movement with Scout Platoon providing pickets to make sure nobody lost direction. He was confident and I think all the company commanders left his O Group with a feeling of confidence that it could be accomplished.”

“PIECE OF CAKE. PIECE OF CAKE. WE’LL TAKE IT. WE’LL TAKE IT.”

The O group was a master class in the dissimulation that, at times, is essential to inspired leadership in dire circumstances. Stewart inspired confidence in all his audience save one. Stewart never forgot it:

“There was only one doubt in anybody’s mind, and that was Stockloser. That’s the first time I saw [Major] Stockloser [OC, D Coy] in his right light. He let me down. And [Major] Pappy Coons [OC, B Coy] said, ‘Piece of cake. Piece of cake. We’ll take it. We’ll take it.’ He [Coons] went up in my estimation terrifically from there on … [Stockloser said,] ‘You’re sending us to our death’ … I ignored it.”

“SINGLE FILE TO THE HIGH GROUND”

As Stewart explained: “I had to improvise … I never went by the book … it is the Tory personality.” His plan called for a battalion-level night-time infiltration of enemy lines with the Anti-Tank Platoon positioned on the Argyll flanks to handle the anticipated German counter-attack.

“I took them in single file to the high ground and luckily it was ‘Hill 195’ and we went right through the German lines. When we reached the top, I advised the company Commanders to dig in and I distributed the [Battalion] about the hill. When it came light in the morning, the German reacted very strongly and shelled our positions.”

The war diarist recorded:

“The Argylls’ attack on Hill 195 took the following form: A circuitous route to the East and North-East of the feature was chosen, as the area to the West was known to be defended heavily by the enemy. The C.O. sketched the route to the Scout Platoon and they went out in advance to piquet the advance of the Battalion. The advance began at 0001 hours, at 0430 hours the leading elements were within a few hundred yds. of the objective, without as yet having encountered any enemy. There the C.O. pointed out to the Company Commanders their respective positions – positions that previously [had] been picked from the map – and the marching troops were despatched to them forthwith with the instructions to search the area for enemy and “dig like hell.’”

“MOVED ONTO THE TOP OF THE RIDGE, STILL WITHOUT OPPOSITION”

Lt Ken Frid, commanded a platoon in D Company:

“… that night we received orders to push on to Hill 195. D Company was vanguard and mine was the leading platoon. I wasn’t too happy about it because it dominated all the surrounding country and I didn’t think ‘Jerry’ would care to give it up as easily as the Intelligence reports intimated. Well, we moved off about 2 a.m., using a circuitous route, and arrived on the objective about two hours later and moved onto the top of the ridge, still without opposition, and very joyfully began to dig in…”

“TOLD WE’D BE WALKING THROUGH THE ENEMY LINE”

According to Pte Bob Post, D Company:

“…We were told to be damn quiet and to follow up this rope or a string they had lined up… I believe we were told we’d be walking through the enemy lines…”

“THE WHOLE UNIT WAS COMING SINGLE FILE”

As Cpl Gord Boulton of the Scouts recalled it, the companies were somewhat less than “damn quiet”:

“…Our platoon led the whole company [sic] up this Hill 195… it was funny, ’cause we were away up, way ahead and the whole unit was coming single file, right, winding behind us. Well, we went up and we were clipping wires and things on the way up, so the Germans weren’t getting messages back. And we went up right through the Germans, okay. And we got up, and we got to the hill, we’re listening and here’s the unit, everybody’s supposed to be quiet, right, and here’s the unit coming up with I don’t know how many hundred men, okay, coming up this hill behind us, and we could hear the shovels hitting the rifles and things like that, you know, and they were supposed to all be muffled, but with that many men…”

“GET A JOB DONE; SAVE LIVES”

The first attempt to take Hill 195 failed with heavy casualties to the BCRs and the Algonquins. Lt-Col Stewart’s plan resulted in success – they took the hill – with no casualties until the next day. It fit perfectly with his summation of the moral trust at the heart of command – “Get a job done; save lives.” The German counter-attacks, which he had anticipated, were repulsed. German shelling took the lives of Lt Boyd and Pte Richard McDonald. For Maj Maclean, the Argylls’ “intense group loyalty” took flame at Hill 195. Dave Stewart’s and the Argylls’ military reputations took root (or flame) at 195 as well.

Historian LCol Brian Reid considers “Dave Stewart’s infiltration … onto Point 195” as one of the examples of “the warrior spirit.” His other examples are small scale by military standards of organization – the section or platoon level. The Argyll action at 195 was a battalion-level with four rifle companies, the Scout Platoon, the Anti-Tank Platoon, the Mortar Platoon, and others in support. Historian Terry Copp considers Stewart’s leadership, along with that of Lt-Col “Swatty” Wotherspoon of the South Alberta Regiment, “outstanding.” Historian LCol John A. English described the Argylls’ action at 195 as “probably the single most impressive action of ‘Totalize.’” There are plenty of plaudits for the intrepid Argyll success at 195 and a portion accrue to Capt Johnston and the Scouts, including Pte Tony Mastromatteo.

Later, in the day, Tony recalls that “I was on the road taking notes for my officer. There was a German tank there bombed and hit, burning.”

Battle’s toll – 29 July to 7 September 1944

Hill 195 provides one prospective for understanding Tony Mastromatteo as an Argyll soldier, an Argyll Scout. The casualties from 29 July to 7 September impart another. It is what Capt Sam Chapman described 40 years after the war as a “history bought by blood.” In that brief period, the battalion lost 84 KIA, including 1 major, 6 lieutenants, and 6 NCOs; the wounded numbered 229, including 3 majors, 2 captains, 7 lieutenants, and 11 NCOs; the POWs were 20, including 1 major, 1 captain, and 3 NCOs. The total was 333 struck off strength between 29 July and 7 September! This figure does not include those injured or sick. On 26 July 1944, the battalion’s establishment was just over 800; its fighting strength 400 to 500. The casualty rate for the former figure is 83.25%; for the latter, it is 66.6%! B and C companies sustained such heavy losses that they were amalgamated into one company following their action at St Lambert (see ASgt Cecil Fisher, Pte Ira Hedman, and Pte “Pop” Burrill).

Plaque at Hill 195 erected by the Argyll Regimental Foundation.

At Moerbrugge, Belgium, the Scouts joined A Company for a diversionary attack north of the village from 8 to 10 September. On 14 September 1944, Capt Johnston was killed by heavy enemy fire just outside of the battalion’s command post at Moerkerke. He was revered and, as Cpl Boulton declared, they all wept.

“AFTER SOME HARD FIGHTING”

In the early morning of 19 September 1944, Lt-Col Stewart “announced … his intention” to attack Sas van Gent, “a fairly large town just inside the Dutch border, on the Neuzen canal.” By 1900 hours, “after some hard fighting,” the Argylls took the town; they suffered three killed in action and six wounded: Pte Paul “Cosy” Cole, one of the Scout Platoon, was among the dead. Pte Jim Doyle, another Scout, recollected Cosy Cole’s gruesome death. Two Scouts were on one side of a railway track; Cole and Pte “Junior” Crawford were on the other. A German soldier waved a white flag of surrender and they stood up to “wave him in.” Another German soldier “machine gunned Cole.” Doyle and his officer “crawled don the ditch … crawled out, and we finally got back.” They sent a carrier up to retrieve Cole’s body and Crawford. The deaths of Johnston and Cole within the space of a few days stunned the Scouts.

“Slow tempo” of operations

In the days after Cole’s death, as Capt Sam Chapman of C Coy, put it, a “slow tempo” of operations replaced the frenzy that had been the norm from early August. From the 14th to the 20th September, seven Argylls were killed in action, including Johnson, LSgt Jess Grey, and Cosy Cole; 16 were wounded. By comparison to the preceding weeks, the losses were comparatively low. The days became “cold and wet” but quiet. There was much-needed time for showers, movies, and short-term leaves to Ghent. There were also much-need reinforcements. Two Argylls were killed between 23 September and 13 October and ten wounded. By mid-October, the battalion was readying itself for the drive on Essen, Wouwse Plantage, and then Bergen op Zoom. On 14 October, Lt-Col Dave Stewart ordered the Scout Platoon and the Pioneers to take Watervliet. Maj Hugh Maclean later wrote that the “jaws of the people involved dropped at this bland pronouncement, but the party set off within a few minutes.” By noon, the Scouts were in the town. Stewart ordered A Company into the town and C Company to “pass through” it and move northwards. But, as Maclean noted, “every day couldn’t be Sunday” and opposition became more noticeable. By 2200 hours C, led by a Scout whose name is unknown, came to a halt about 1,000 yards beyond the town because of “shellfire and small arms.” Pte Jack Reibeling probably died that night.

“SOME OF ITS MOST EXHAUSTING, TRYING, AND LEAST REWARDING BATTLES”

The Argyll battles in the Scheldt ended on 16 October and the battalion moved out that day “through Antwerp to an area near Brasschaert, in the pine forest two miles north of the city.” For Maj Hugh Maclean, the “coming days were to see the Regiment involved in some of its most exhausting, trying, and least rewarding battles.” “Symbolically,” he wrote, “summer was ending … Grey, stormy days, bleak mornings and cheerless afternoons and cold, shivering nights lay ahead.” The approaches to Essen would be stained with Argyll blood.

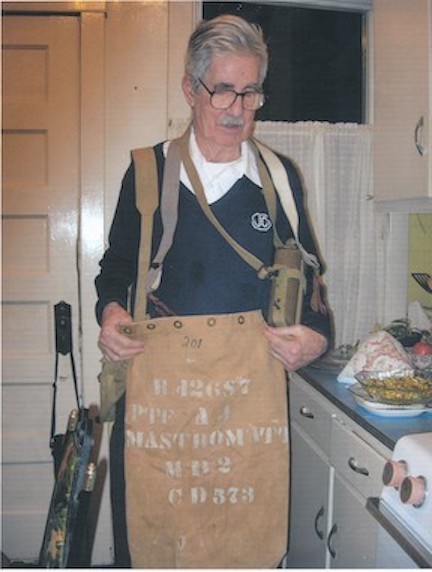

In the fighting from 15 October to 4 November, the Argylls lost 39 killed in action and 140 wounded. Among those killed were Pte Alexander Nickoloff, Pte Bill Du Trizac, Cfn Bert Hunt, LCpl John Marshall, and Capt J.S. Prugh. Lt Norm Donaldson was wounded on the 29th while leading his platoon of A Company across the causeway at Bergen op Zoom. Pte Mastromatteo was tasked to take him back to the Regimental Aid Post (RAP). It was “about 1400 hours,” Tony recalls. “I was taking the officer out because he was wounded.” They were in a schoolhouse and a German “tank fired”… I sure as hell didn’t hear anything; I saw blood coming down my leg and arm.” Pte Mastromatteo did, as always, his duty: “I got the officer on a jeep and [then] I went to First Aid [RAP], and then an ambulance. By 9 p.m. in Holland, I was in hospital.” In terms of the fighting, Scout Mastromatteo’s war was over. “I did not go back to the front, I stayed in Holland.”

Pte Mastromatteo’s experience in battle is framed by the casualties incurred. From 26 July to 6 December 1944 (the death of Pte Alex Laba), the losses were: 151 killed in action (or died of wounds), 458 wounded, and 32 prisoners of war, for a total of 641 lost to the battalion, largely in three months (August, September, and October). The figure does not take into account those struck off strength because of sickness or accident. During the course of the war, the battalion’s wartime establishment was just over 800. The war diarists, and later Maj Maclean, routinely gave 400 as the unit’s fighting strength (or roughly the equivalent of the four rifle companies: A, B, C, and D). It was higher. Support Company comprised the Pioneer Platoon, the Mortar Platoon, the Anti-Tank Platoon, and the Carrier Platoon). The Scout Platoon was attached to battalion headquarters and under the direct command of the CO. There were casualties within Support but it was a “bubble,” as Col Earp has described it, not decimated by relentless casualty reports. Pte Tony Mastromatteo was one of the last of the 641 casualties sustained during those months. He had been in almost continuous action through August until mid-September, and then again in the “exhausting” and “trying” battles of the Scheldt.

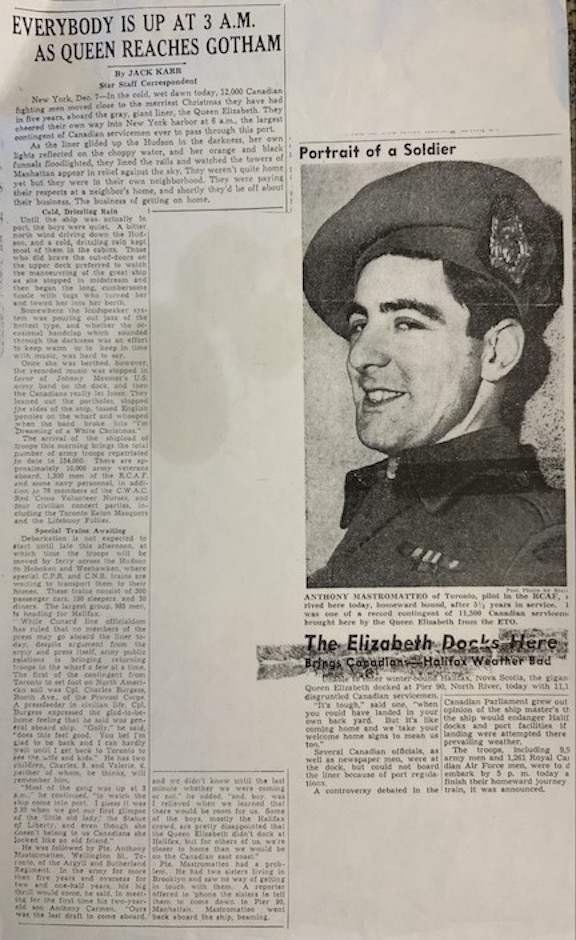

“I was the second last person to get on the Queen E[lizabeth], landed in New York harbour [on 7 December 1945], and a news guy grabbed me and asked if I had anything to say, got in touch with my sister, my oldest sister, Rose, and she was by the window.” Tony had two sisters living in Brooklyn and the reporter contacted them. His big thrill would come, he said, in meeting his son, for the first time, his two-year old-son, Anthony Carmen.

“Portrait of a Soldier,” Toronto Star.

From there, Pte Mastromatteo travelled by train to Toronto. There, he got his wish. “I met my wife at Union Station” in Toronto. I saw Carmen for the first time. He said, ‘That’s not my daddy!’” Mary and Carmen lived “with my Dad’s sister.”

“A new life” – “if something needed to be done, you just did it”

It “was nice to be back here to stay. Shortly after, we bought a house, new house,” Pte Mastromatteo says. It was “all set and ready to move into a new life and we did well ever since.” I “never got to Italy [however], 101 years in this country.” He worked as a mutual clerk at the racetrack and as a crossing guard in the Beaches. Tony and Mary raised three children: Carmen, John, and Laura. Of her father, daughter Laura writes: “Tony was a good father, quiet. He believed that if something needed to be done, you just did it.” Her observation captures almost perfectly her father’s attitude to the war and battle.

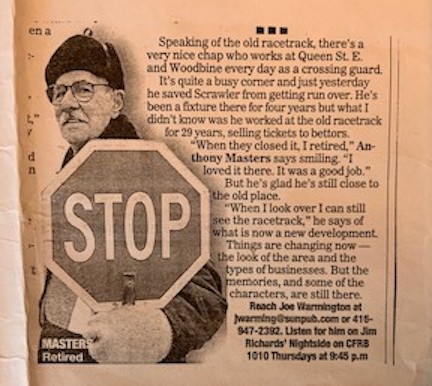

When the old Woodbine Racetrack closed in 1993, Tony retired. “He worked at the old racetrack for 29 years, selling tickets to bettors. ‘When they closed it, I retired. I loved it there. It was a good job.’” He then became a crossing guard at Queen Street East and Woodbine “every day” for four years (1997). He was “glad he’s still close to the old place…. When I look over I can still see the racetrack,” he told a reporter, “smiling.”

Tony was a long-time member of the Toronto Branch of the 1st Battalion Veterans’ Association. He appears 17 times in the Albainn, the veterans’ newsletter. Often, he won the 50/50 draw or the “booze” draws at their meetings. The editor noted in the 1990s that his racehorse, appropriately named Albainn Gu Brath, had a number of second- and third-place finishes in sulky racing. The editor congratulated Mary and Tony on their 50th anniversary in the February edition of 1993. Another time, he noted that Mary had three brothers who fought at Kapyong in Korea and that, at times, Tony marched with the Korean veterans in the annual Warriors’ Day Parade at the CNE.

In the 1990s, Laura noted: “Mary and Tony joined the regiment on two trips back to Holland. This was a significant highlight for them both. Mary’s uncle, Percy Pollock, is buried at Bergen Op Zoom. In 2014, Mary and Tony moved into Sunnybrook Veterans in Toronto. In 2017, Tony was asked to represent Sunnybrook as one of four veterans for the 150th Anniversary of Canada’s Confederation at a Blue Jays game. Again, in 2019, Tony was asked to represent the Army, along with a fellow veteran from each of the Navy and Air Force, at a Blue Jays game in honour of the 75th Anniversary of D-Day. The gentlemen went on the field and each threw the first pitch.”

On Pte Mastromatteo’s 101st birthday, a deputation of serving Argylls – Maj Mike Wonnacott, CD, Drill Sergeant Major Glenn Seddon, CD, and Piper Cpl Alistair Sanderson – brought Argyll birthday greetings to him at Sunnybrook. It was a fitting Regimental tribute to the long life and distinguished service of a proud Argyll veteran.

Looking back – “I wouldn’t want to do it again, that’s for sure – once was enough!”

Pte Mastromatteo said, “I was in it [the war].” He has “no regrets, I did it, did what I was supposed to. I wouldn’t want to do it again, that’s for sure – once was enough!” He considers it “a shame about the Ukraine, [it’s] too bad.” “I was a little boy then, I’m an old man now.”

Pte Anthony Joseph Mastromatteo, Scout Platoon, continues to wear his Glengarry and medals proudly. He hopes to join the Argylls for the Garrison Remembrance Service on 13 November. “I took it as it came, took it easy, took it as I was supposed to, took care of those around me, that’s my job…. I lasted…. You just did it, that’s all, walk, crawl, whatever.” The Toronto Star covered the story of the returning Canadian soldiers in December 1945. It featured a picture of Pte Mastromatteo wearing his Argyll balmoral and cap badge; it is entitled it “Portrait of a Soldier.” The caption captures Pte Mastromatteo’s life from 1940 to 1945 – he was the portrait of a soldier. He was in the army for 5½ years, 2½ of them as an Argyll. Yes, Pte Mastromatteo, you did do it, you did all of it.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Mastromatteo outside a Bell tent.

7-9 Draper Street, Toronto, today.

St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church Toronto, c. 1950s.

St Mary Catholic School, 20 Portugal Square, Toronto.

Tony grew up at 605 Wellington Street, Toronto.

Tony’s parents, Maria and Luigi, in the centre. Tony is behind his mother. Photo taken at the wedding of his sister Rose.

Duffs’ recruiting picture.

Tony in short pants outside the barracks.

B Company, Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles of Canada, Christmas Day 1941.

Camp Otter Point, B.C.

Playing bugle at Camp Nanaimo, August 1941.

In khakis with his bugle, possibly in front of the armoury.

Military band, with Pte Mastromatteo in the front row in the foreground.

Pte Mastromatteo.

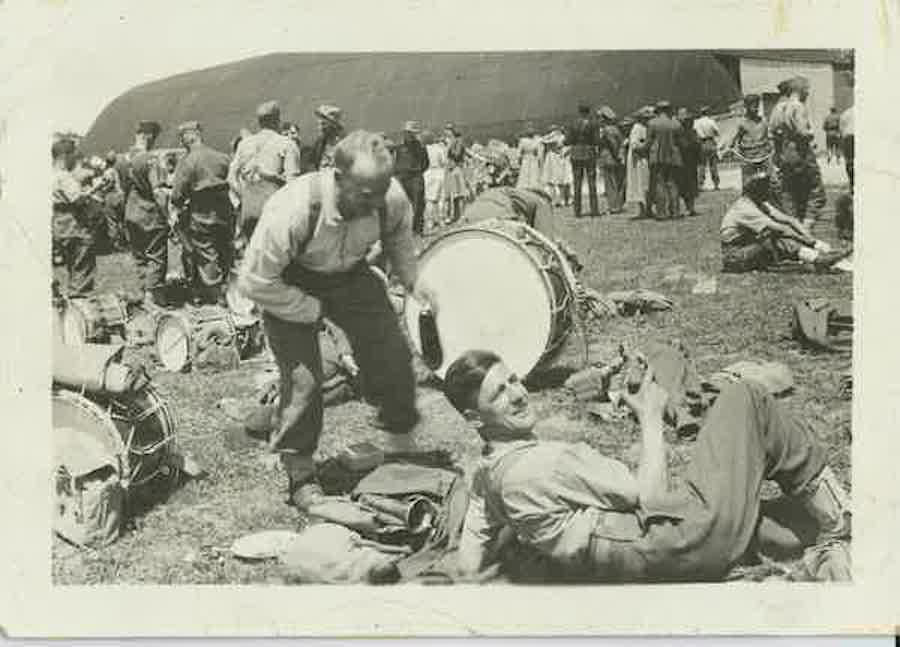

Band resting during training.

Pte Mastromatteo shaving.

On guard duty.

The bugles and drums relaxing.

Outside the barracks.

Training group.

In front of the canteen. Pte Mastromatteo is in the back row, fourth from the left.

Pte Mastromatteo with his rifle.

Mary and Tony’s wedding, 1943.

Mary (at right) with Tony’s sister Lucy.

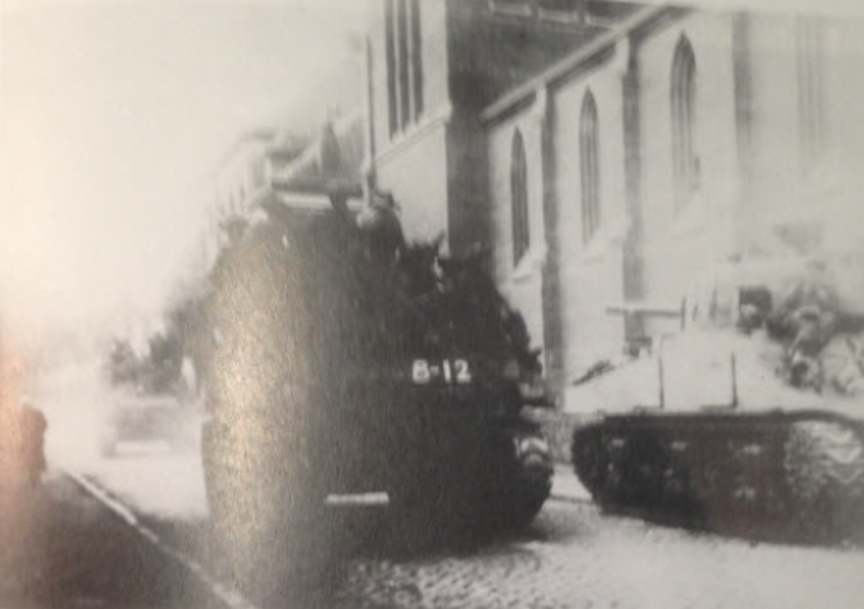

Argylls playing cards beside their Bren gun carrier, Sas van Gent, 19 Sept. 1944.

Argylls on SAR tanks at Sas van Gent, 19 Sept. 1944.

Tony and Mary in their younger days.

With his wartime duffle bag, canteen, and possibly an ammo pack.

Tony and Mary.

Recognition as a crossing guard.

Attending the 2021 Remembrance Service.

Maj Mike Wonnacott, DSM Glenn Seddon, and piper Cpl Alistair Sanderson celebrate Tony’s 101st birthday.

Birthday celebrations earlier this year.