Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

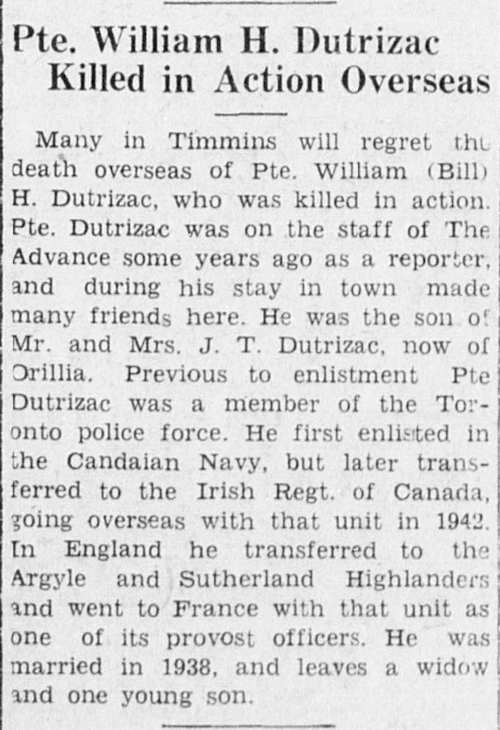

The posts for Ptes Jack Reibeling, Alexander Nickoloff, Gordon Marr, and Bill Patrick covered the end, as Maj Hugh Maclean later put it, of “the Argylls’ part in the fighting on the western reaches of the Scheldt, and around what later became known as the ‘Breskens pocket’.” The post for Maj Alex Logie took up the Argylls’ re-entry into the field of battle on 20 October 1944. Two Argylls were wounded on the 21st and four more the following day. The 23rd was another bloody page in the unit’s history – 6 KIA , including LCpl Norman Hubert James, and 24 wounded – as the battalion fought its way on the approaches to Wouwse Plantage. Today’s post provides a rudimentary outline of the life of Pte Bill du Trizac, one of the 13 Argylls killed on 24 October 1944.

I offer my thanks to Matt Scarlino of the Toronto Police Service and Michel Emery, a distant relative of Pte du Trizac, for their assistance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

“nightmarish fighting”

War Diary. 24 October 1944 [C.T.B.]

The night was a peculiarly nasty one: pitch dark, with a cold rain falling. The road to the forming-up position, at best only a narrow dirt track, had been churned up by the rain and the tanks into a quagmire. On either side of the road was a deep and low-lying, soggy ground so that bypassing was out of the question. Because of these conditions the group was not formed up and ready to move until 0445 hrs.

At 0515 hours forward elements had gone 400 yards beyond the S.L., and it looked as if surprise had been obtained. Then the leading tank in attempting to by-pass a road block (a knocked out enemy S.P. gun) became immobilized in the ditch. At the same time, houses nearby were set afire either by our own or enemy fire, so that the whole force was silhouetted. The Infantry (“A” and “C” Companies) were forced by heavy enemy S.A. fire to stop their advance and to deploy on either side of the road. A tank that succeeded in getting forward beyond the Infantry was knocked out by a bazooka.

The position in the morning remained unchanged, with the exception that enemy mortars, hitherto quiet, became very active. Apparently they had the area ‘taped’: The road was constantly laced with fire, and tac H.Q. already severely battered during its tenancy by the Lake Superior Regiment on the preceding day, was a favourite Jerry target.

The C.O. felt that it was still possible to obtain the objective, and ordered “B”-Company to come forward and to be ready to reinforce “A” and “C”. At 1600 hours a new attack was launched, but this, too, was unsuccessful. The tanks could make no progress against bazookas and an 88 mm. commanding the approaches to the town. “B”-Company, moving forward, was caught in a mortar concentration, and its Company Commander, Capt. McGivney, was killed. [In addition, the A/CSM, Charles MacDonald, was wounded].

The C.O. appreciated that no further attempt could be made … to take the town: The men were exhausted by the nightmarish fighting at the beginning of the operation and by the constant battering to which they had been subjected by enemy mortars. Finally, their tank support was virtually gone. At 1800 hours we were informed that our forward companies would be replaced by two companies of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment.

[KIA: Capt Raymond G. McGivney, L/Sgt Patrick F. Stephenson, Pte Joseph W. Campbell, Pte William H. Du Trizac, Pte Reginald R. Harrison, Pte Robert W. Hiller, Pte Verdun Honsberger, Pte Lloyd W. Hutchings, Pte Allan J. Lefurgey, Pte Clive A. Mills, Pte Michael A. O’Neil, Pte Sidney R. Overacker, and Pte Eino R.J. Roivas. Wounded: 20.]

Interview. Pte Sam Resnick.C Coy

I was asked to go and take a message to him [L/Sgt Stephenson]. I can remember distinctly, crawling through the trench … and some of the men had shit themselves. And not that I was a great hero, [but] I was told to go and find him. So I was trying to go and find him, and he’d been hit and he was lying up on top [of the trench].

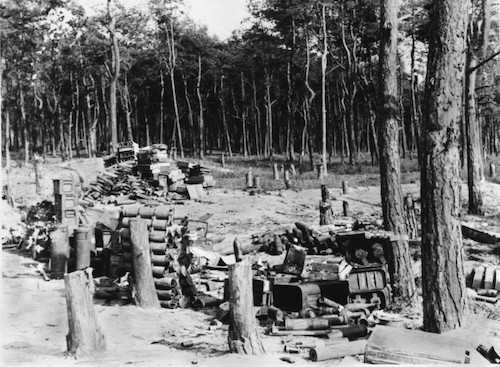

Ditch at Wouwse Plantage.

Interview. A/Cpl Burt Eden. B Coy

I didn’t even get into the town [Wouwse Plantage]. I was in the ditch, then the tank shot the church steeple off and then they put the shells right in the ditch and they got me.

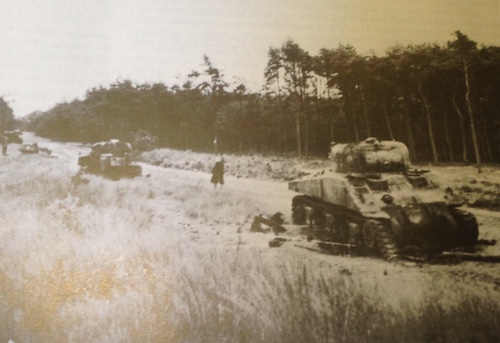

Church at Wouwse Plantage, 24 October 1944.

Interview. Major Bob Paterson. OC, C Coy

He [Lt-Col Stewart] didn’t like casualties. Nobody does, but I think that gradually it wore him down … at Wouwse Plantage…. I was putting in a second attack or something, and Stewart … and he’d sent a carrier up – Red Cross carrier – to get me out, to see what the hell was going on. And he shouldn’t have sent a Red Cross carrier up, that ain’t cricket; but I got in it anyway and I got back. And then Brigade was telling him to put in a third attack, and he’d just … switch off the radio outside the window, and he said, “Listen to this … how the hell can I attack?” And Jesus, everything was coming down. And I don’t know whether that teed off Brigade or not, but I remember him doing that … when the Regiment was at stake, he wouldn’t back down.

Wouwse Plantage, Netherlands, 23 October 1944.

Wouwse Plantage after the battle, 24 October 1944.

Pte William Henry Du Trizac (1915–44) (B 79557)

KIA 24 October 1944

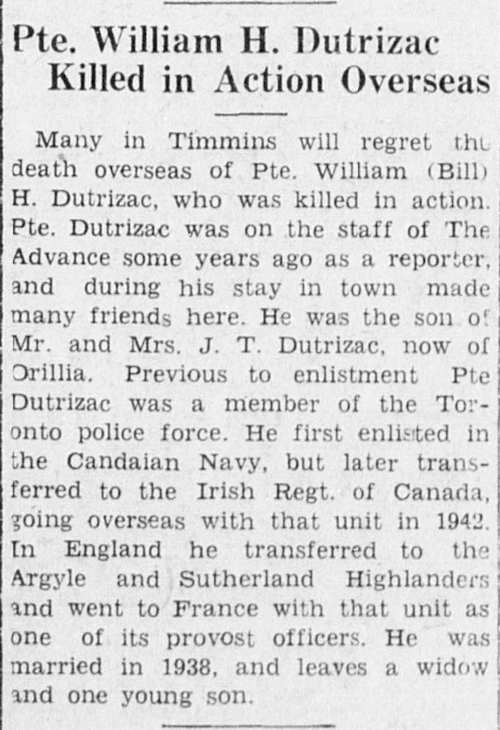

Joseph Treffle du Trizac (1893–1951) was born in Montreal; his family moved to the Ottawa Valley in Ontario shortly after his birth. He married Gertrude Anne Wilson (1894–1974) in Arnprior in October 1915; she gave birth to William Henry in Renfrew on 4 February 1916 (he signed his name Dutrizac, du Trizac, and Du Trizac at various points in his life). He attended separate school in Renfrew, and completed grade 12 and two years at technical school. He was a member of the Renfrew Collegiate Institute boys’ basketball team in 1932. Attracted to military service, he served with the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish from 1930 to 1934. His employment history prior to moving to Toronto was varied: a cook/caterer in Levack, a mine town near Sudbury, making $13 weekly; a shipper in an Ottawa brewery, making $18 weekly; he also had three years of mixed farming experience (sufficient that he considered himself capable of owning and running a farm). His obituary in the Timmins Advance states that Bill Du Trizac worked as a reporter for the paper.” During his stay in Timmins, he “made many friends.” The Perth Examiner published an obituary on 7 December 1944. It provides additional details about Du Trizac’s newspaper career:

Mr. Dutrizac was formerly on the staff of the Perth Expositor and later was manager of Class “A” Weeklies of Canada and still later with the James A. Fisher Advertising Agency and is now identified with the Orillia Packet and Times.

Bill Du Trizac moved to Toronto in 1935, completing one academic year at Western Technical and Commercial School in May 1936. He joined the Toronto Police Department in November 1937, making $33 weekly. There is no mention of a newspaper career in Bill Du Trizac’s army personnel file. Moreover, the likelihood of a career as varied as the one suggested by the two obituaries is problematic for a young man who was only 20 when he moved to Toronto and joined the Toronto Police Department in 1937. It seems that his life had been conflated with that of someone who had the same name or possibly that of his father, who was an “executive.” Bill’s personal life changed on 28 September 1939 when he married Jeannette (Janette) Emily First in Toronto; their son, William (“Billy”) Treffle du Trizac, was born on 8 April 1940 in Toronto. They lived at 123 Humberside Avenue with his two sisters.

“duty”

Du Trizac’s obituary states that he joined the Royal Canadian Navy in 1939; if so, there is no record of it in his personnel file. His younger brother, James Treffle (“Treff”) Du Trizac (1919–2011), joined the 48th Highlanders in 1940. William enlisted with the Irish Regiment of Canada in Toronto on 14 June 1941 (he signed “Du Trizac”). Bill was 6’, 1”, 195 lbs, with brown eyes, and dark brown hair. His wife was “expecting.” By mid-July, he was stationed in Halifax and hospitalized for a number of days in May, July, and August – 26 days in all – with tonsillitis, influenza, and gastroenteritis. Interviewed on 17 November 1941 (two days after the death of his daughter), he gave “duty” as the reason for joining the army. His deportment was “casual”; his disposition “agreeable”; his appearance (grooming) “rough”; and his appearance (physical) “strong build.”

“must have had plenty experience handling men as a policeman”

The officer observed:

This man seems well placed. Excellent learning ability but possibly too lazy to accept responsibility of N.C.O. However must have had plenty experience handling men as a policeman.

The comment about laziness is at odds with most observations about Du Trizac and may be explained by his circumstances in terms of enlistment and the circumstances facing his wife. His background with vehicles was extensive: heavy and light trucks, automobiles, and motorcycles; he had had one motorcycle accident. He played rugby and basketball, collected stamps, enjoyed woodworking, and played the piano. Surprisingly, Du Trizac’s “A” score on the “M” tests drew scant comment other than “excellent learning ability,” despite the rarity of such a mark. Pte Du Trizac left Canada on 29 October 1942, arriving in England on 5 November. Bill and Jeannette’s daughter, Harriet Anne, was born on 14 November 1942 and died the next day. Through 1943 and 1944, Pte Du Trizac took several courses, qualifying as a driver, cook, and driver mechanic; he also took the battle drill course.

“He was very anxious to get to the Argylls”

As part of the infantry reinforcement unit for the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, Pte Du Trizac disembarked in France on 2 September 1944, joining A Company of the Argylls on 12 September in Belgium as a driver mechanic, part of the draft of 81 reinforcements “much needed after the casualties [of August and early September].” Capt Sam Chapman of C Coy remembered:

I rode in the carrier Dutrizac drove – He took the Carrier battle wing at that time … and I brought him through to the forward rfl coy on that mad trip through France + Belgium. He was very anxious to get to the Argylls.

“war and its trials … a nasty dirty job and this next business looked of that type”

The introduction to battle came quickly with the fighting at Moerkerke, Zelzate, and Sas van Gent, followed by a short lull, then the resumption of fighting and dying, on 15 October. “There were no illusions,” Maj Hugh Maclean wrote, “about the forthcoming campaign.” The Argylls who had survived since July “had no illusions.” They “regarded war and its trials and discomforts as … a nasty dirty job and this next business looked of that type.” It would be, they thought, “a tough go.” Had there been any illusions, the last weeks of October 1944 would have shattered them.

“nightmarish”

On the 23rd, B and D companies bore the brunt of the fighting. Late that night, Lt-Col Dave Stewart received orders to take the town of Wouwse Plantage the next day. He ordered A and C companies to lead the attack. The unit’s war diarist, Lt Claude Bissell (“learn a word a day, the Bissell way”), a man never at a loss for words, characterized the fighting on the 24th as “nightmarish” and the conditions were awful.

The night was a peculiarly nasty one: pitch dark, with a cold rain falling. The road to the forming-up position, at best only a narrow dirt track, had been churned up by the rain and the tanks into a quagmire. On either side of the road was a deep and low-lying, soggy ground so that bypassing was out of the question. Because of these conditions the group was not formed up and ready to move until 0445 hrs.

At 0515 hours forward elements had gone 400 yards beyond the S.L., and it looked as if surprise had been obtained. Then the leading tank in attempting to by-pass a road block (a knocked out enemy S.P. gun) became immobilized in the ditch. At the same time, houses nearby were set afire either by our own or enemy fire, so that the whole force was silhouetted. The Infantry (“A” and “C” Companies) were forced by heavy enemy S.A. fire to stop their advance and to deploy on either side of the road. A tank that succeeded in getting forward beyond the Infantry was knocked out by a bazooka.

The position in the morning remained unchanged, with the exception that enemy mortars, hitherto quiet, became very active. Apparently they had the area ‘taped’: The road was constantly laced with fire, and tac H.Q. … was a favorite Jerry target.

The C.O. felt that it was still possible to obtain the objective, and ordered “B”-Company to come forward and to be ready to reinforce “A” and “C”. At 1600 hours a new attack was launched, but this, too, was unsuccessful. The tanks could make no progress against bazookas and an 88 mm. commanding the approaches to the town. “B”-Company, moving forward, was caught in a mortar concentration, and its Company Commander, Capt. McGivney, was killed [in addition, the A/CSM, Charles MacDonald, was wounded].

The C.O. appreciated that no further attempt could be made … to take the town: The men were exhausted by the nightmarish fighting at the beginning of the operation and by the constant battering to which they had been subjected by enemy mortars. Finally, their tank support was virtually gone. At 1800 hours we were informed that our forward companies would be replaced by two companies of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment.

“men staring gloomily out over a bleak, barren, landscape”

“Heavy rain” and “thick mud” did not help the situation made much worse by small arms fire, mortaring, and fire from anti-tank guns. A and C companies “crouched miserably in their half-flooded foxholes, the men staring gloomily out over a bleak, barren, landscape, while sniping and mortaring answered any movement.”

“fiendish” – “weary and battered”

The mortar concentrations were little short of “fiendish” leaving A and C companies “weary and battered.” “Fatigue, cold, and wet” played as great a part, Maclean thought, as the enemy in the failed attack. The rifle companies were also under strength and the training of the reinforcements a matter of concern. Thirteen Argylls died that day; 20 were wounded. Of the casualties, only one was an original Argyll, one of the enlistments from 1940 and 1941). Of those killed in action, 11 of the 13 have been identified by their rifle company: A – 2, B – 2, and C – 7. Pte Bill Du Trizac, A Company, was one of the dead. It is not known when or how he died; suffice it to say that the day offered plentiful opportunities.

“Too bad about Dutrizac”

On 6 December 1944, Capt Sam Chapman, C Company, wrote his wife:

Too bad about Dutrizac [sic] – peculiarly enough I knew him – though not well … I knew that he had been killed. His wife will get a letter from an A Coy officer. I could write her if you think it’s worth while. He was killed during the early stages of the drive which wound up in Bergen-op-Zoom. When I get back I’ll see if I can find out anything interesting about it.”

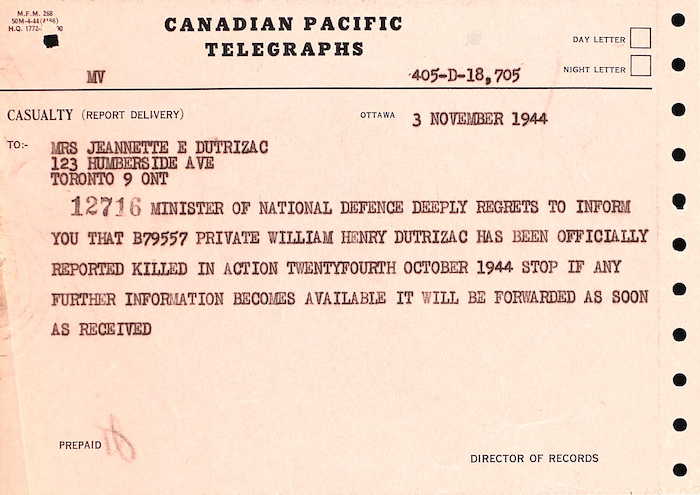

Jeannette Du Trizac received the dreaded telegram announcing her husband’s death. The life-altering news changed the course of her life and that of her son. Shortly thereafter, she left Toronto to live in Orillia near her in-laws. Doubtless she received, as Capt Chapman suggested, a letter from an officer in A Company and possibly one of his comrades. She would certainly have received a letter from Padre Charlie Maclean, providing as much information as he could glean of her husband’s death and offering solace and some consolation. By day’s end on the 24th, he would have 33 such letters to write and 13 funeral services to prepare. And, doubtless, the Toronto Branch of the Argyll Women’s Auxiliary offered their comfort and support as it always did.

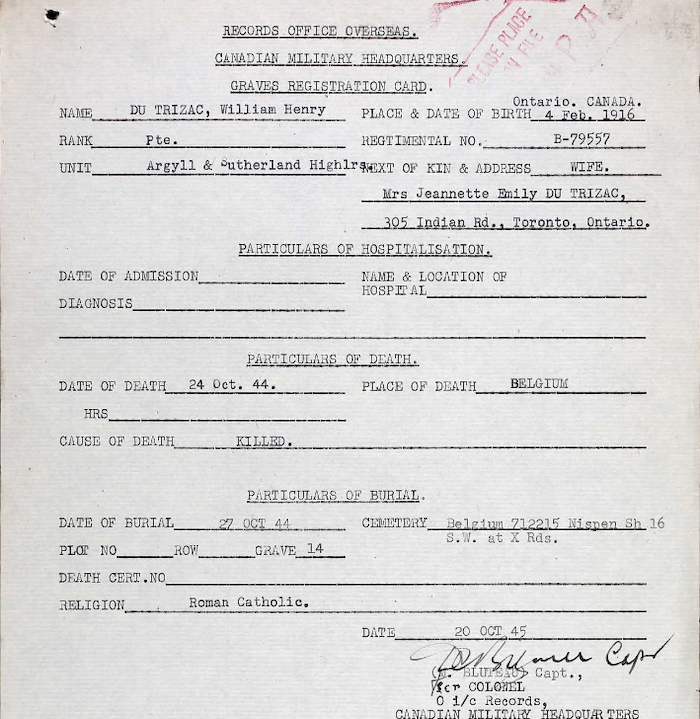

Padre Maclean buried Pte Du Trizac on 27 October 1944 in the customary Argyll manner at “Nispen, Belgium [Netherlands] S.W. at X Rds.” The Allies had liberated Nispen the previous day. Bill Du Trizac had been “very anxious to get to the Argylls” and now, he, too, had joined its “shadowy company” of the dead. Charlie Maclean, a piper, and a small group of Argylls said goodbye. The battalion did as it always did, and had to do – it moved on.

Du Trizac left 2 Argyll cap badges, a balmoral, a tobacco pouch, a “Glorex” pen and pencil, a pocket watch (“Chrometre”), photos, a rosary, a bracelet, a change purse, six wallets, two souvenir notes, nine souvenir coins, five religious medallions, his identity disc, and a membership card. His bank account with the Dominion Bank contained $70.90, and he held five war savings certificates with the Bank of Toronto. He did not own the home at 123 Humberside in which he lived with his wife, his son, and his two sisters.

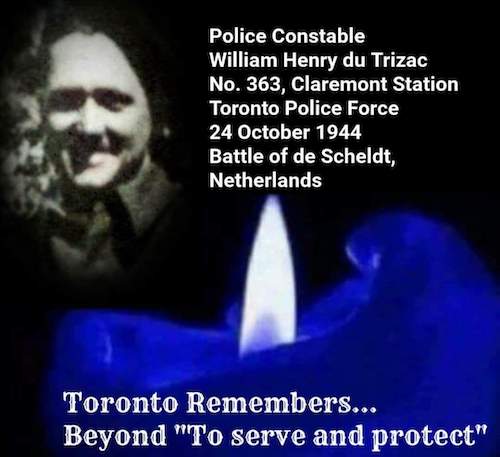

Pte du Trizac’s name appears in family trees and it seems that direct family survive. In 2018, distant relations visited his grave in the Canadian War Cemetery at Bergen-op-Zoom, placing maple leaves and poppies. And, of course, the Dutch never forget. Renfrew Collegiate Institute remembers him in its social media postings every Remembrance Day. The Toronto Police Service recognizes Pte Du Trizac’s service.

The Emery family places a poppy on the grave of Pte William Du Trizac, 8 October 2018.

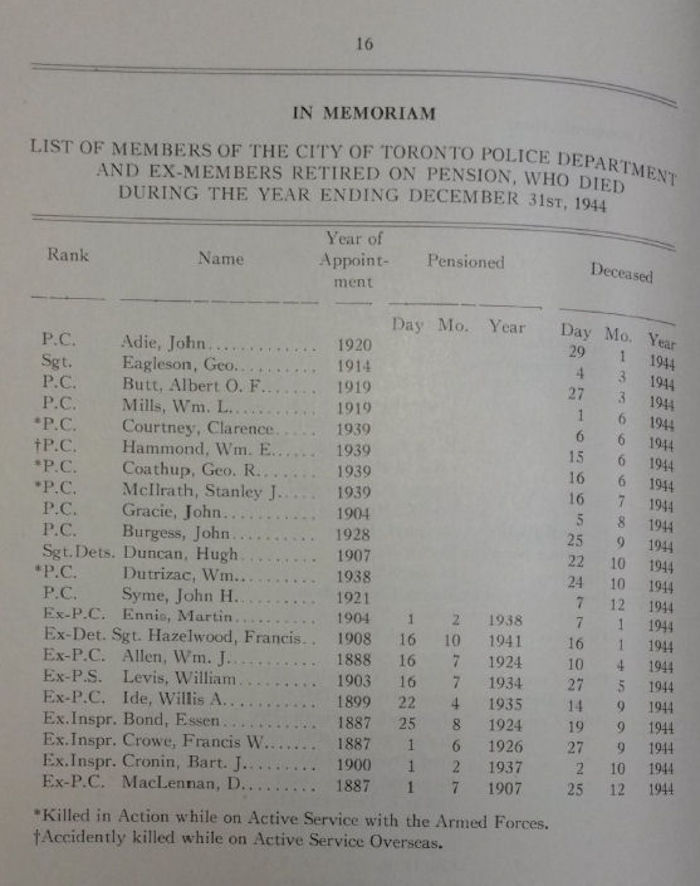

“In Memoriam,” police chief’s annual report, 1944.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Du Trizac’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Above and below: Pte William Henry Du Trizac.

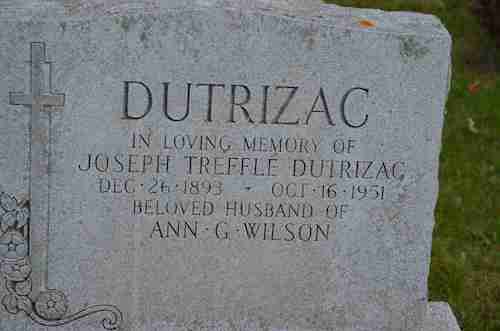

Pte Du Trizac’s father, Joseph.

Western Technical and Commercial School, Toronto.

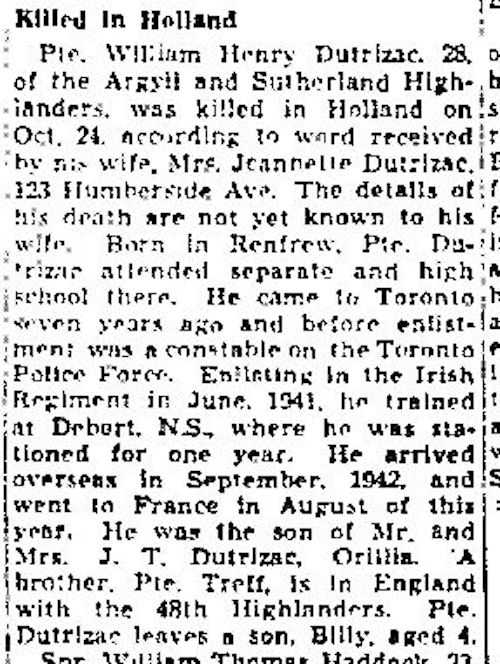

Obituary, Globe and Mail, 5 December 1944.

Blue-and-white marbled Glorex pen like the one found among Pte Du Trizac’s personal effects.

Grave marker, Canadian War Cemetery, Bergen-op-Zoom.

Above and below: Second World War memorial in Orillia, Ontario.

Gravestone at St Michael’s Cemetery, Orillia.

Toronto Police Service memorial, Constable du Trizac.