Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

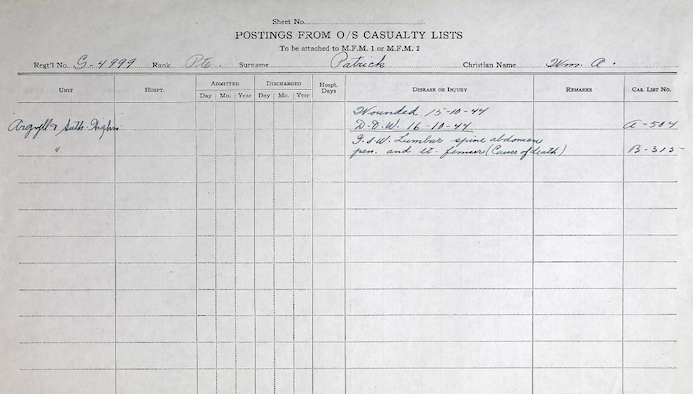

Last year I became interested in the Argylls’ dire need for reinforcements after the blood-letting of six weeks of battle. I wondered, too, about the reinforcements themselves. I did poppies last year for Ptes Alexander Nicholoff and Gordon Marr. Pte Patrick was wounded on the 15th and died the following day. I wanted to know more about him and now I do. Unfortunately, I have to date had no success in finding an image of him or family.

I thank Dr Vivian McAlister, OC, himself a renowned surgeon and historian who did five tours in Afghanistan as a surgeon with the CAF. Vivian confirmed that Maj Angus D. McLachlin, who operated on the seriously wounded young private in the late hours of 15 October 1944, was the famed surgeon of the University of Western Ontario.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte William Miller Adamson Patrick (1923–44) (G 4999)

DW 16 October 1944

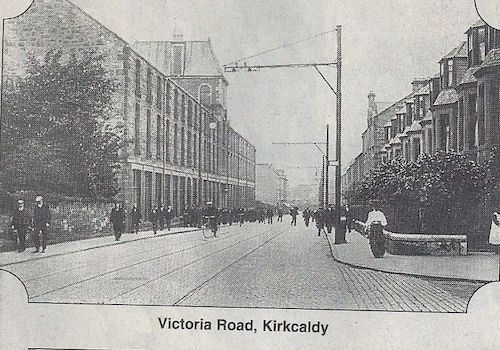

William Miller Adamson Patrick was born on 7 July 1924 at Kirkcaldy, Scotland, the son of William Patrick, a First War veteran, and Minnie Millar Patrick; his parents married there on 7 November 1919; he had a brother and a sister. Kirkcaldy in Fife on the east coast of Scotland was a spinning and weaving centre. The family immigrated to Canada in 1925 on the RMS Antonia. The inter-war years of the 20th century were one of the last great surges of Scottish emigration. Canada was always a favoured destination, and the Scottish immigrants of the 1920s, especially from the Lowlands, were in search of opportunity. The Patrick family found its new home in Hampton, New Brunswick.

“worked in store and delivered by truck”

William Patrick enlisted in Saint John, New Brunswick, on 3 May 1943. He had served in the 2nd Battalion, New Brunswick Rangers from September 1941 until his enlistment. He was 5’, 5¾”, 132 lbs, with a dark complexion, brown hair and eyes. His brother, Thomas Patrick, was on “active service” in Belgium. The medical officer gave him a category of AII, probably because of slight myopia in his right eye. On 4 May, the personnel selection officer noted that Patrick had “Finished Grade 9 at Hampton, King’s Co. at 17 years.” “After school,” he “worked in [a] grocery store [for] half a year.” Then, he “worked in store and delivered by truck druing [during] the past year.” He had “5 yrs School cadets.” In terms of his time with the Rangers, he “Went to camp summer of 1942.”

“much concerned about two things (a) to avoid the infantry (b) to be a motor mechanic”

Patrick’s comments elicited an interesting appraisal by his personnel selection board officer:

LEISURE ACTIVITIES: Reads newspapers. Goes to church. Skiing, skating and hockey, fishing.

GENERAL: Single. Parents living. Father (a 1914–18 veteran) janitor of school. Has one brother and sister both older. Brother in 3rd Coastal Arty.

This man was a quiet and serious fellow but much concerned about two things (a) to avoid the infantry (b) to be a motor mechanic.

His “M” score showed distinctly better than average performance in general observation and better than average educational development. These facts combined with his extreme disinclination for the infantry (having been warned away from it by his father) are the reasons for the R.C.A. allocation.

Based on his appraisal, the army examiner recommended: “R.C.A. – Automotive Driver I.C. (N.T.).

“very anxious to join his brother who is in Coast Artillery”

Pte Patrick was taken on strength on 14 May at #71 Basic Training Centre (BTC) in Edmundston, New Brunswick. The interview process for enlistees at this stage of the war was continuous. On 6 July at #71 BTC, the interviewer reported:

This man made good in basic training. Hard worker. Young but serious and ambitious. With time he might become N.C.O. material. He complains of sore feet. He is very anxious to join his brother who is in Coast Artillery. Original allocation confirmed – R.C.A. – Coastal Defence.

“Original allocation confirmed – R.C.A. – Coastal Defence.”

Coastal defence it was and he was taken on strength as a gunner at A-23, Halifax, on 18 July 1943. Three days later, at Elkins Barracks, the barracks that housed the gun crews manning the batteries there, a new recommendation arose: “Considered suitable for training in Drivers Bty.” Patrick’s daily rate of pay was raised to $1.50 on 3 November 1943. He had a 14-day furlough in November 1943, a four-day pass on 21 December, and then five days “Xmas leave” on 28 December. He had another four-day pass from 11 to 14 March 1944. As a result of a charge under section 40 of the Army Act, he was awarded four days confinement to barracks on 30 March 1944.

“Suitable for C.I.C. overseas”

Pte Patrick’s army life had taken a change of direction and this was further change in store. He was re-interviewed at No. 1. Transit Camp, Windsor, Nova Scotia, on 25 April 1944:

Driving since August ’43 and qualified driver i.c. class III. B.T. at 71 C.I.T.C. and advanced training at A-23 R.C.A.

Suitable for C.I.C. overseas. Authority H.Q.S. 20-6-22 F.D. 183 (Org. Aeal) Ottawa, 19 April 1944.

“… state of training suitable for operation duty o/s C.I.C”

Patrick was struck off the strength of No.1 Transit Camp on 20 May 1944. The change in direction accelerated its pace. A personnel officer examined Patrick’s documents on 7 July 1944 at Camp Debert, Nova Scotia: “… state of training suitable for operation duty o/s C.I.C. Qual. Dvr. i/c Class III.”

“Suitable for Gen Services Inf. Fd. Unit”

Pte Patrick went overseas on 19 July 1944 arriving in England on the 27th and taken on strength at #3 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU). There was more to come and it would complete the change of direction. A personnel selection officer reviewed Patrick’s file at #3 CIRU and concluded: “Suitable for Gen Services Inf. Fd. Unit.” An infantry field unit in northwest Europe was a long way for coastal artillery in the Maritimes. Patrick went to the X-4 list (unposted infantry reinforcements) on 31 August 1944. The Argylls took him on strength on 15 September 1944 posting him to C Company commanded by Maj Bob Paterson.

“shellfire and small arms”

On 14 October Lt-Col Dave Stewart ordered the Scout Platoon and the Pioneers to take Watervliet. Maj Hugh Maclean later wrote that, the “jaws of the people involved dropped at this bland pronouncement, but the party set off within a few minutes.” By noon the Scouts were in the town. Stewart ordered A Company into the town and C Company to “pass through” it and move northwards. But, as Maclean noted, “every day couldn’t be Sunday” and opposition became more noticeable. By 2200 hours C came to a halt about 1,000 yards beyond the town because of “shellfire and small arms.” Pte Jack Reibeling probably died that night.

“casualties when a shell landed in their midst”

At 0430 hours on the morning of the 15th, the unit’s carriers and Wasps got across the bridge built the previous day by the Pioneers and joined the rifle companies. German resistance had weakened and there were enemy stragglers “all very tired and confused and in a thoroughly bad state of morale.” The advanced companies stopped for lunch about noon. It was “prepared under difficulties; shells were landing all around Pte. McIntosh’s chosen cookhouse and snipers kept letting rounds go between the potato peelers.” “Farther forward, most of No. 15 platoon [C Company] became casualties when a shell landed in their midst.”

“a whole series of incidents that got to me”

“There were,” Pte Art Bridge, C Company, recalled, “a whole series of incidents that got to me.” On the night of the 14th, there was the death of the Argyll “hit” by Germans “outside the little house that we were in.” “The poor guy [possibly Pte Jack Reibeling] died out there that night.” Cpl Harry Ruch, A Company, wrote a preface to his diary, a sort of compensation for what he deemed to be its inadequacies in conveying anything close to what happened in battle:

“very sticky and dirty and cause us almost as many casualties”

In action situations are happening every second and every second seems an hour so only a small fraction of what happened can be catalogued. It will be noted that the term “a quiet and uneventful night” has been used quite often. This statement will prove misleading to the uninitiated as I refer to a quiet night etc. compared to the noisy ones we had been through. There was never really a quiet night at the front. One was always on the alert and expecting anything.

Another term which will prove to be misleading is when I refer to “no opposition”[.] This should not be taken literally as it does not take into account the brief skirmishes with small enemy parties, rearguards and patrols which were constantly in evidence. It was just that it was not a heavy prolonged engagement like the Seine, Caen, Falaise, the Albert, etc but they proved to be very sticky and dirty and cause us almost as many casualties as the big ones. This type of fighting happened quite often.

“A shell struck it, killing the occupants immediately”

By 15 October 1944, Lt Claude Bissell, the unit’s Intelligence Officer and war diarist also made his daily entries in a similar manner. The small actions and the “brief skirmishes,” regardless of how “sticky and dirty” often went unnoticed. Pte Reibeling’s death on the 14th and C Company’s close encounters with Germans attacking a “little house” with perhaps a section or a platoon passed without remark. So, too, did the shelling and sniping of C Company’s position on the 15th. The former killed Ptes Alexander Nicholoff, Gordon Marr, and Muir Marlatt. HCapt Charlie Maclean, the battalion’s padre, wrote to Lolly Marr, Gord Marr’s wife: “The Germans were heavily entrenched on the other side of the canal. The fighting was very severe, but the Canadians drove the enemy back. Marr and a companion were fighting from a house. A shell struck it, killing the occupants immediately.”

“general anguish got to me. I couldn’t do anything. Funny feeling.”

For Pte Bridge, the night of the 14th and the day of the 15th were “sticky and dirty” as Cpl Ruch would have it:

The next day, we were getting ready to push on up the road and an artillery barrage came down, and I was shooting out a window of the house and a shell came and hit the house right where I was, and it blasted me – my nerves – bad as a result. It knocked me down and one of the fellows that was with me in the same room. He was sitting on a chair and shrapnel took two legs off the chair and down he went, in that chair. That, and the continued barrages, and no sleep, and general anguish got to me. I couldn’t do anything. Funny feeling.

“Case would appear hopeless”

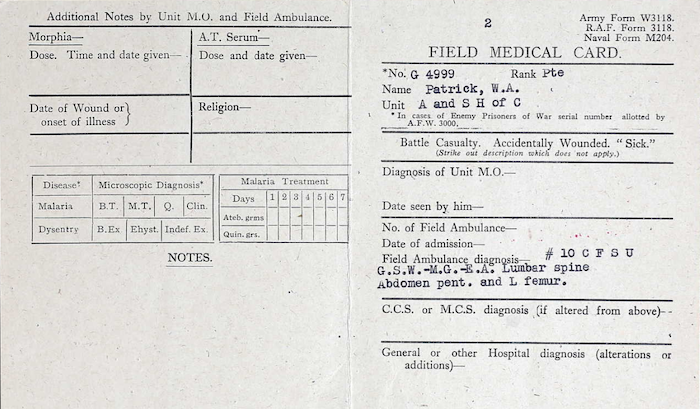

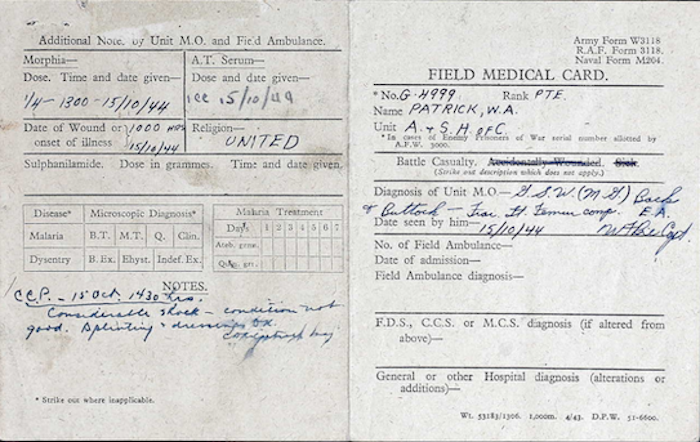

Pte Bill Patrick, C Company, was wounded at 1000 hours on the morning of the 15th. It was a “G.S.W. (M.G.) [gunshot wound machine gun). The Argylls medical officer (MO), Capt Bill Bie, examined him at the Regimental Aid post and made that assessment of the cause of the wound and his diagnosis: “Back + Buttock – Frac. Lt. Femur comp.” Patrick received morphine at 1300 hours. At 1430 he was in “Considerable shock – condition not good.” The “Splinting + dressing” by the stretcher-bearers and possibly the MO, were “OK.” By 1600 hours Patrick was in the 4th Canadian Field Transfusion Unit. He was in “GRAVE SHOCK. No P no B.P.” He was “so shocked at present difficult to get operation.” After some treatment, at 1900 hours, his condition “is still grave” and doctors suspected bleeding “from a large abdominal vessel.” There was also a “spinal cord lesion” although it was difficult to ascertain its “exact posn.” “Case would appear hopeless.”

“A very poor risk and little prospect of survival … operation seemed only hope”

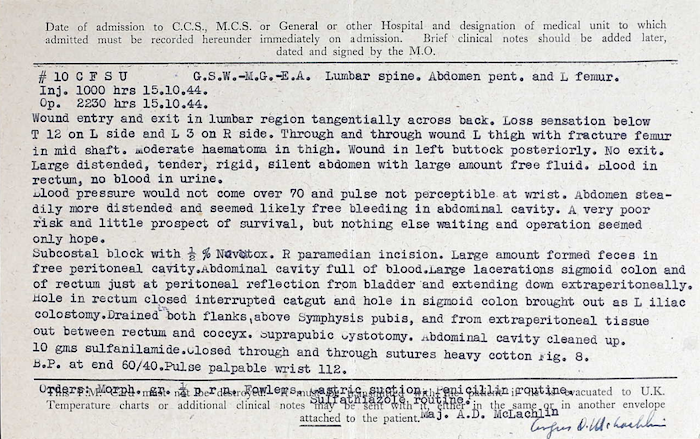

Patrick was moved to #10 Canadian Field Surgery Unit where, at 2230 hours, Maj Angus D. McLachlin (a renowned surgeon in the post-war) operated. Patrick’s condition was poor. His abdomen was distended probably from “free bleeding,” his blood pressure “would not come over 70 and pulse not perceptible at wrist. Yet, McLachlin operated and left his humane assessment: “A very poor risk and little prospect of survival, but nothing else waiting and operation seemed only hope.” At the operation’s end, Patrick’s blood pressure was “60/40” and “Pulse palpable wrist 112.” Before the procedure, there was no “perceptible” pulse.

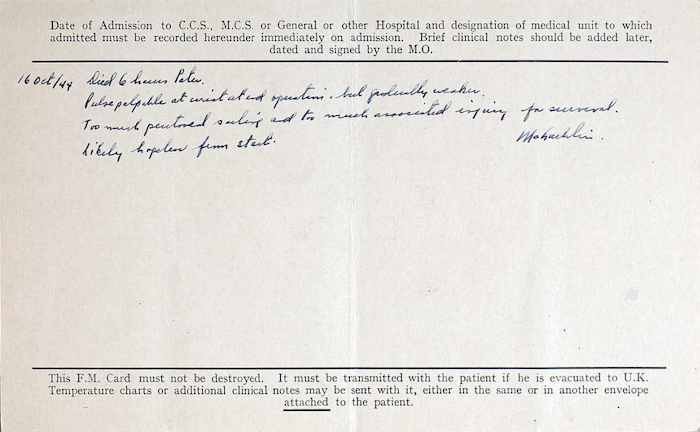

“Died 6 hours later … Likely hopeless from the start”

On 16 October 1944, Maj McLachlin made his last notation on Pte Patrick’s Field Medical Card:

Died 6 hours later.

Pulse palpable at wrist at end operation, but gradually weaker.

Too much peritoneal soiling and too much associated injury for survival. Likely hopeless from the start.

Another C Company Argyll received the same humane medical assessment on 6 December 1944. Capt Norman C. Delarue, a surgeon, thought the gravely wounded Pte Alex Laba “should be given the benefits of any chance that operation offered him.”

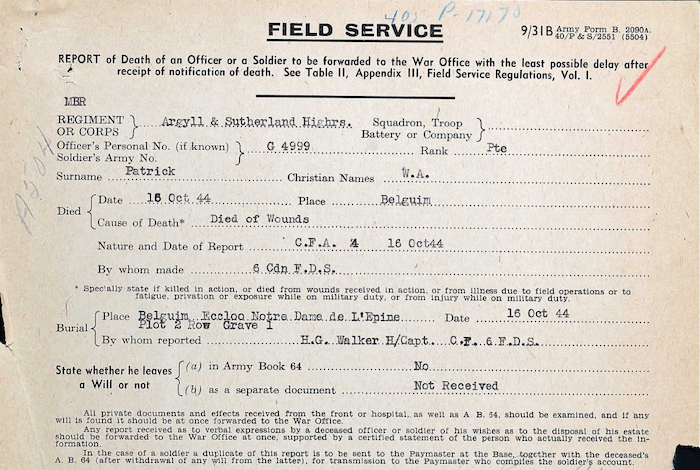

Pte Patrick was buried on the day he died at “Eccloo Notre Dame de L’Epine.” Pte Marr was buried the same day but in a different location. HCapt Charlie Maclean, the Argylls’ padre, performed Marr’s service and signed his Field Service Card. It appears that HCapt H.G. Walker of the 6th Field Dressing Station performed Pte Patrick’s. Patrick died away from the unit and the Argylls moved to “its new concentration area” at 1300 hours on the 16th. Four Argylls were killed in action on the 15th and 12 were wounded; all were from C Company, all were recent reinforcements. Yet the unit entry for the day took no notice. Battle, as Cpl Ruch, astutely noted after he was out of it, provides a different perspective on a day’s events. For Pte Bridge, however, was in the centre of the small encounters that caused C Company’s casualties that day. For him, it was different:

That, [the previous night’s fighting and the day’s fighting] and the continued barrages,

and no sleep, and general anguish got to me. I couldn’t do anything. Funny feeling.

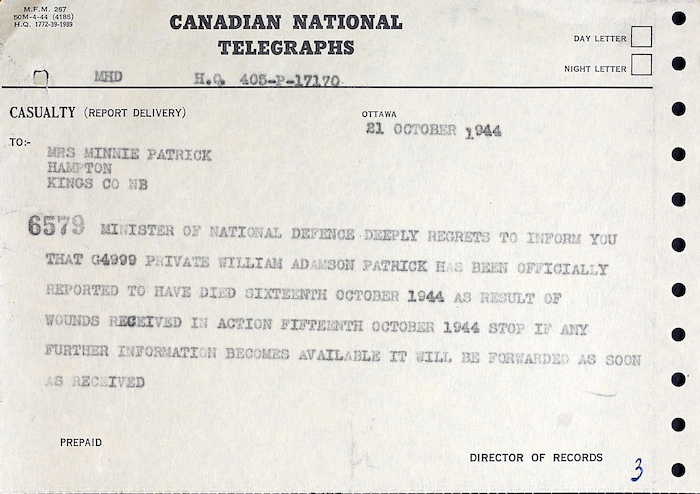

The director of records informed Minnie Patrick on 24 October 1944 that further to the telegram of 21 October, “your late son died as a result of bullet wounds to the spine, the abdomen, and the left femur.” Next of kin had the opportunity to choose an inscription for a Canadian war grave. Pte Patrick’s family selected:

GREAT IS THE LOVE

OF A MAN

WHO LAYS DOWN HIS LIFE

FOR HIS FRIENDS

At enlistment, Pte Patrick determined to follow his father’s experience-based admonition “to avoid the infantry.” With the cooperation of personnel selection officers, he succeeded for a time. The infantry desperately needed reinforcements as the experience of the Argylls in their first six weeks of fighting proved. Pte Patrick became a rifleman, and he died as one.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Patrick’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Victoria Road, Kirkcaldy, Scotland.

RMS Antonia, circa 1922–30.

Mortar ranges, Camp Sussex, New Brunswick, 1943.

Aerial view of Devil’s Battery and Elkin Barracks, circa 1943.

Devil’s Battery, circa 1943.

Devil’s Battery, Hartlen Point, Eastern Passage, Halifax (modern view).

Maj Bob Paterson – a lieutenant at Nanaimo, B.C., in 1941.