Introduction

In February, I pondered how to represent the battle for Veen on 7 March 1945. Nine Argylls died there on that black, cold, and confused night. All but one was a recent reinforcement, and their names were largely unknown to me. The list ran from the bottom of one page to the top of the next. The name at the top of that page was “Madaire, Wilfrid [sic] E.” [see Pte Wilfred Ernest Madaire]. Several French Canadians had served in the 1st Battalion and his life intrigued me. I looked up his file on Ancestry and reviewed the others as well. I found that two of the Argylls killed that day were black; moreover, two of the Argylls captured at Veen were also black.

Over the past few decades, historians have paid, and properly so, more attention to the issue of race and recruitment. Racial discrimination is an indisputable fact of Canada’s military past. That said, their history of service is old. Blacks served with loyalist forces such as Butler’s Rangers during the American Revolution. Indeed, one of them, Richard Pierpoint, was an ex-slave who settled in the Niagara peninsula after the war, settled in St Catharines, fought again as a member of the “Coloured Corps” during the War of 1812, and was one of the earliest settlers in the area of Fergus [see Richard Pierpoint].

James Munroe Franklin (1897-1916) was American-born and lived in Hamilton before the First World War. He was employed as a clerk at Parke & Parke, the city’s foremost drugstore. One of the owners, Harold Parke, was an officer in the 91st Canadian Highlanders (the name later changed to the Argylls). On 26 July 1915, Franklin enlisted with the 91st (Parke signed his attestation paper). In the space beside “complexion” on the form, there is one word – “Negro.” Franklin immediately went to the 76th Overseas Battalion; the 91st sent a large draft (300 in total) to it; Parke commanded it; Franklin was there along with his employer. The unit was broken up overseas for reinforcements; Franklin went to the 4th Battalion and was killed in action on 6 October 1916.

During the First World War, Hamilton was part of the recruiting district commanded by Major-General William Alexander Logie, one of the 91st’s founders and its first commanding officer. He faced directly the racially motivated opposition to the enlistment of blacks and indigenous people to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. On 18 November 1915, Sam Hughes, the minister of Militia and Defence sent him a telegram, asking: “Is it true that Colored men in Toronto are refused admission to our service.” Logie was a broad-minded individual. He replied the same day:

“Absolutely no truth in statement that colored men in Toronto are refused for overseas service stop Last summer question arose here and I ruled they must be accepted stop Several colored men including one Sergeant in overseas battalions in camp at present time.”

Walter Hamilton Bruce commanded the 91st when Franklin enlisted. Bruce left in December 1915 to take command of the 173rd Canadian Highlanders, an overseas battalion raised by the 91st. He opposed Logie’s integrationist policy. As the 173rd’s CO, Bruce has gained unfavourable notoriety for his response to a query on the acceptance of black soldiers: “Sorry,” he wrote, “we cannot see our way to accept [Negroes] as these men would not look good in Kilts.” As Pte Franklin discovered, enemy shells were non-discriminatory.

When Canada declared war in September 1939, racial discrimination was official policy. At the outset the army, navy, and air force restricted service on racial grounds; the army, however, changed its policy in 1940. Canada’s black population was tiny. In 1941, it was about 22,000 or .2% of the population. The 1st Battalion mobilized in June 1940 and went overseas in July 1943; it included all manner of ethnic and religious groupings as well as indigenous recruits. Hamilton was close to the Six Nations reserve near Brantford and there were indigenous Argylls from mobilization; there were, however, no blacks.

After the return from Jamaica in May 1943, the Argylls lost a large number of older soldiers and some who were medically unfit for overseas service. The unit received a large tranche of reinforcements from Camp Shilo, Manitoba, in early July and went overseas later that month. In the United Kingdom, there would be more reinforcements. On 1 October 1943, the unit marched from the field to its new quarters at Riddlesworth Camp, the “dirtiest camp we ever moved into” recalled Pte John Booth of the Mortar Platoon. That night at 2000 hours 142 reinforcements arrived. They were on battalion parade the next day and addressed by the Argylls’ new commanding officer, Lt-Col Dave Stewart. It was a memorable day for Sgt Robert “Bun” Tapping, D Coy, in several regards:

“… we got a bunch of recruits … [RSM] Pete McGinlay was out looking them over, you know, and there was one coloured fellow. Well, Pete walked right up to him and says, ‘A fine looking Scotsman you are.’ The poor fellow, he didn’t know, what to do, you. It’d make you feel foolish to have something like that [happen].”

The soldier’s name is unknown unfortunately.

Did race make a difference to the battalion? Lt Alan Rathbone, Mortar Officer, commented on the gradual change in the composition of the battalion after mobilization:

“Most of us came from the east end of Hamilton, which was Old Country: old English, Scottish families. There were certainly Italian fellows [and] I remember a Jewish fellow … I don’t recall a black fellow until reinforcements arrived in England and France … You were not accepted or rejected on the basis [of name, religion, ethnicity, or race] …”

And no matter who you are or what you are – colour, creed or anything – you are one of them”

RSM McGinlay’s comment to the new Argyll notwithstanding, he changed. Sgt Kurt Loeb knew the RSM well during the war. He often remarked of the RSM that once you wore the Argyll cap badge nothing else mattered; you belonged. Pte James Farrell, a Second War veteran remarked that, “in the army … it’s hard to explain – you’re automatically a friend, you’re one of them. And no matter who you are or what you are – colour, creed or anything – you are one of them and that’s it.” Tom Kedney, another private and fellow veteran, described a “fantastic bunch of fellows. And when you talk, ‘One for all and all for one’ … I can honestly say that means for everything they have, for their mind, for their possessions, for everything. And the esprit de corps type of thing … I’m certainly glad that I went though it and I’ll never experience that type of thing again.” Regiments, good regiments that is, derive their sustaining power from this quality, an experience rare in society.

The casualties incurred by the Argylls in the months of fighting brought successive allotments of desperately needed reinforcements [see Pte Alexander Nickoloff and LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr] as the 1st Battalion wrote successive pages of its history in red. Indigenous soldiers such as Pte Edward John Howe, a Mi’kmaq from Nova Scotia, came to the Argylls overseas. Black soldiers joined the Argylls as reinforcements from September 1944 to at least March 1945. Pte Lorimer Lee Johnson, from Nova Scotia, arrived on 1 September 1944; was wounded on 20 October 1944; returned to the unit; and was killed in action on 21 April 1945. Pte Ernest Robertson Smith (KIA) joined the battalion on 1 February 1945, as did Pte George D. Johnston (POW); Pte Clarence Richard Vaise (KIA) was taken on strength on 1 March 1945, as was Pte William A. Courtney (POW).

Of the 51 Argylls killed, wounded, and/or captured on 7 March 1945, at least four of them were black. The face of Argyll death that fateful day had two colours: black and white. The page of Argyll history written that day had one: red.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Pte Edward Robertson Smith (B 159850) (1915–45)

KIA 7 March 1945

There is considerable historical lore about the Underground Railway that took American slaves on a journey to freedom in British North America; its terminus was in St Catharines, which, in the 1850s, had been the home of prominent black abolitionists such as Harriet Tubman. Recent scholarship has shown that the black population of Upper Canada (Ontario) in the 1860s was lower than most estimates and that the proportion of ex-slaves was lower than supposed. St Catharines was one of the leading centres of black settlement and, in 1861, had the fourth largest black population in the province.

Edward Robertson Smith’s family provides a glimpse into the connections among the province’s scattered black communities, whether in Windsor, Niagara Falls, St Catharines, or Toronto. His father, Edward Anderson Smith, hailed from Niagara Falls. When he married in 1913, he was 33, “Divorced,” and a letter carrier. Edward Robertson’s mother was Maude Inez Bloom (née Plummer); she was born in 1878 in Windsor (her father was born in Upper Canada and her mother in Indiana); she married William David Bloom, a black doctor in St Paul, Minnesota, on 18 November 1905; their daughter Leila M. Bloom was born on 7 June 1906. In 1911, she was living with her parents, sister, and daughter in Toronto. According to the census, she was a “school teacher” and the family was “Negro.” By the time of her marriage to Edward A. Smith on 15 July 1913 in Toronto, she, too, was “Divorced.”

Edward Robertson Smith was born in Niagara Falls on 31 July 1915. On his enlistment papers, he listed Leila Hogan (née Bloom) as his “step sister.” Unfortunately, there are no copies of interviews by personnel selection officers in Smith’s personnel file. Hence, the details of his early life are scant. He had 8 years of public school, 2 years of high school (“commercial”), and 1 year (“technical”), all in Niagara Falls. He left school at 16 in 1931. That year his mother died of “carcinoma of the right breast” on 12 March 1931; the “contributing cause” was “Exhaustion.” She was buried in the Fairview Cemetery. Smith’s father had remarried by 1935.

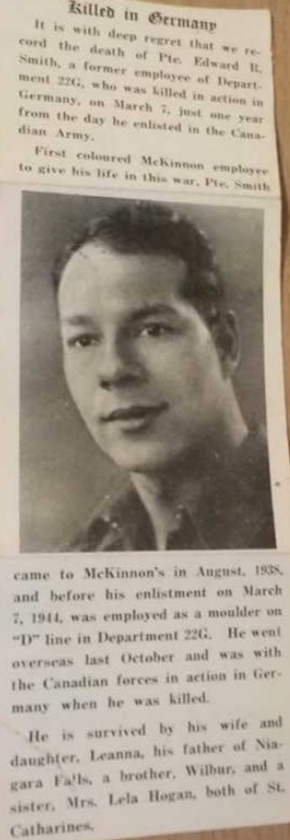

“take [a] course as diesel motor mechanic”

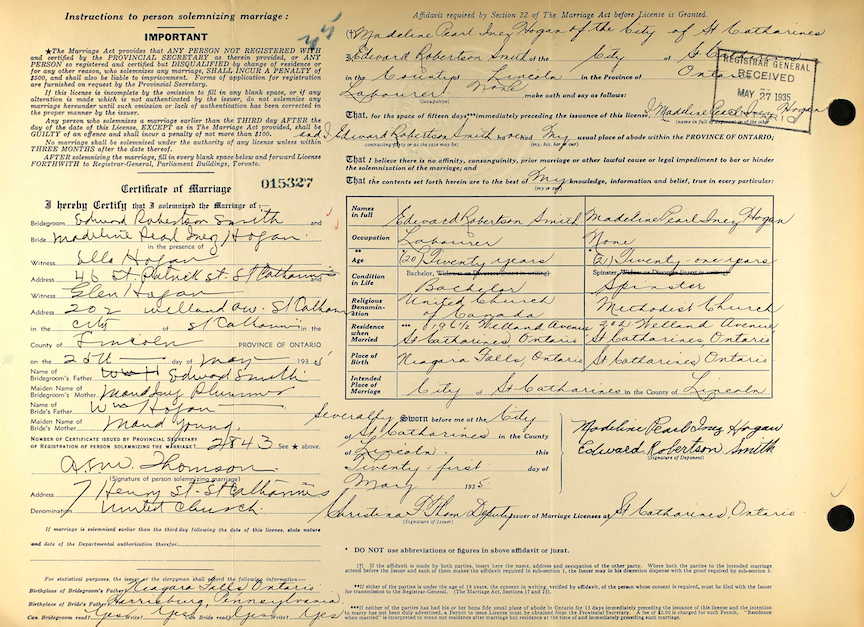

Smith’s employment history from 1931 to 1938 is unclear. His file shows that he worked two years in a restaurant as a stock keeper and he had two years of other work. In 1935 he listed his occupation as a labourer, living at 196½ Welland Avenue in St Catharines. He married Madeline Pearl Inez Hogan (1914-48) on 21 May 1935 at the Welland Avenue United Church in St Catharines; she lived at 202 Welland. Their daughter, Leanna Madeline Inez Smith (1935-2010), was born there on 25 October 1935. Smith joined McKinnon Industries in St Catharines in August 1938, where he worked as a machine moulder “on ‘D’ line in Department 22G.” General Motors bought out the factory in 1929. With the outbreak of the war, it geared production to supplies for the war effort. At his enlistment Edward Smith indicated that he had been promised re-employment at McKinnon’s upon his discharge; he did not, however, wish to return. Instead he hoped, after the war, to “take [a] course as diesel motor mechanic.” The young family rented a house at 63 Vine Street and attended the Welland Avenue United Church, where they had been married.

Edward Robertson Smith’s marriage certificate, 1935.

Edward Smith enlisted in Toronto on 7 March 1944; he was 5’, 8½”, 143 lb, with brown hair and eyes, a scar on the right side of his chest, and a small one on the front of his left shoulder. Three days later, he received a six-day leave of absence and presumably returned home. Trooper Smith of the Canadian Armoured Corps Training Regiment (CACTC) transferred to #24 Basic Training Camp (BTC) in Brampton on 31 March. On 29 May, he was struck off strength there, went AWOL, lost five days’ pay, and was taken on strength at No.2 TR at Camp Borden on the 30th. Trooper Smith qualified as a Class III Driver (W[heeled]) on 6 July 1944. He was AWOL again on 31 July for a little over 9 hours and confined to barracks for 7 days and lost a day’s pay for his minor indiscretion. He was granted 14 days’ furlough and two days special leave from 27 August to 11 September; again, it is likely he returned to St Catharines.

“G.D. [general duties] Infantry”

On 12 September he was reposted from #2 CACTR to #1 Trained Soldier Regiment (TSR). On 10 October, he went overseas, arriving in the UK on the 20th. He was posted to the Winnipeg Grenadiers on 4 November and then to 3 Canadian Infantry Training Regiment on the 18th. On 6 December 1944, he was listed as “G.D. [general duties] Infantry,” a fateful phrase that ensured combat in his immediate future. At this point, Pte Smith had qualified on a range of small arms: rifle, light machine gun, sub-machine gun, pistol, grenades, and PIAT.

“buzzbombs”

On 28 December, Smith was taken on the X-4 list (unposted reinforcements in a theatre of war belonging to a unit or corps), embarked in the UK that day, and disembarked in northwest Europe the next. He joined the Argylls on 6 February and was posted to C Coy. The early days of February were mild, then “dull and wet,” with a rigorous training program set up by the new CO, Lt-Col Fred Wigle. The battalion had just recently suffered casualties at Kapelsche Veer or, as Maj Bob Paterson described it, “this barren bit of isolated wasteland.” The battalion was stationed in Waalwijk, and the month “opened on a peaceful note, most welcome after the turbulent week that preceded it.” Moreover, the weather was milder, or “warm and mucky,” as Capt Sam Chapman put it. The new reinforcements arrived to a new training program, time on the ranges, flare programs to illuminate the other side of the Maas River (the flares were decidedly uncooperative for the most part), “buzzbombs” overhead, patrols, a unit move to Elshout on the 10th, more rain, and occasional movies.

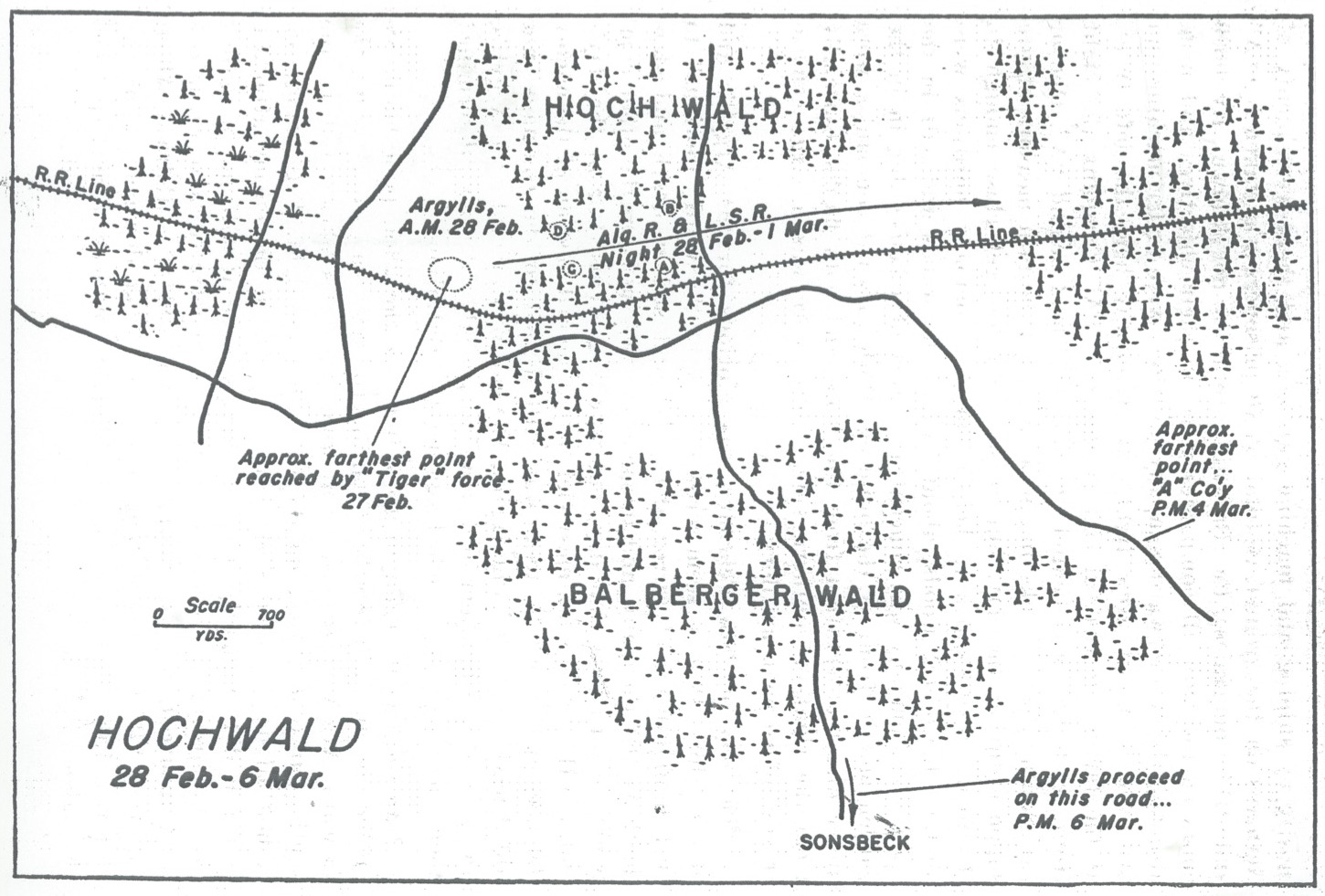

“pinned down most of the morning by heavy enemy mortar and MG fire”

On 22 February, at “0243 hours the C.O. led the Battalion into Germany. By 0300 hours the entire Battalion was in the ‘Reich’.” They were led “by a single piper at the head” of the whole unit. The Argylls were concentrated around Hau, “a little village [that] was fairly thoroughly destroyed.” C Company was part of “Snuff” force a divisional battle group [see LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr]. On 26 February 1944, C and D Companies cleared buildings in the Hochwald Gap. They were “pinned down most of the morning by heavy enemy mortar and MG fire.” C Coy’s OC, Capt Norm Donaldson, was fatally wounded by mortars and Lt Reg Cleator, one of the platoon commandeers, was also wounded. Command of the company fell to the only remaining officer, Lt Doug Beale.

“We [C Company] lost all our officers before we got on the first objective”

Pte Alan Rawcliffe of 13 Platoon, C Company, recalled:

“Just a lot of Tiger tanks and stuff like that. That’s where Reg Cleator lost his leg. Right then, I was with him. He was on one side of a bush, there were three houses up … [near] the first objective. And we lost all our officers before we got on the first objective.”

15 Platoon “under Cpl Dempsey cleared a group of houses,” which netted them a bag of 150 prisoners and 50 civilians. At 2200 hours that night, C and D Companies were relieved: “a hot meal was brought forward … and the men were able to spend a night comparatively free of enemy interference.” Pte Smith’s first day of battle had been a bloody one for his company. The next day, the Argylls pushed into the Hochwald; Lt-Col Wigle held C in reserve.

“we were getting the hell beat out of us”

On the 28th, the Argylls advanced into the Gap. C Company advanced on the southern side behind A Company. They reached it by 0415 hours, “encountering concentrated MG fire.” “All companies,” the unit’s war diarist reported: “suffered casualties by the enemy’s incessant shelling and strafing.” The German counter-attack on B Company’s position began about 0645 hours [see Lt Hugh John McCutcheon]. Lt Doug Beale recounted:

“we were getting the hell beat out of us with mortars and big howitzers coming in, breaking off great big trees, and we hurried through and got into slit trenches that were there up on the far side of the trees.”

“being shelled all that night”

Pte Rawcliffe remembered “being shelled all that night.” Pte James Patrick Murray was one of those wounded by high explosive shells: “they put a high explosive in there and it came back and cut the legs off one fellow, my Bren gunner, hit him in the side of the head and he was cut up pretty bad. I got a piece in my leg … and I walked out.” The next day, what was left of C Company approached a house that was their objective. Sgt Frank McEvoy said, “Jeez, you know, you should put something into that house.” They fired a PIAT round into the house and “got about forty or fifty prisoners.” By “breakfast time” on 1 March, all of the Argyll companies in the Gap had been relieved.

“four days of unexpected activity”

From 1 to 6 March, the Argylls were non-operational. The weather turned colder and CSM George Mitchell, the famed CSM of C Company, returned to the unit on 4 March; his diary entry for the day was brief: “ ‘C’ Coy.” The next day, “after four days of unexpected activity,” the battalion left the Gap “concentrated in the general area of the woods, waiting for the word to proceed towards Veen.” There was some mortar fire from the enemy, resulting in casualties in C Company. The Argylls spent the night of the 5th “in the woods, exposed to the pouring rain, sheltered in slight trenches.” Mitchell’s diary captures the day in one word: “Active.”

On 6 March at 0800, the forward element of a large, combined arms battle group moved out of the woods near Sonsbeck towards Veen: it included C Squadron of the South Alberta Regiment’s tanks and C Company of the Argylls. From that time until 1400 hrs, progress was delayed by mines, the “impassable condition of the ground even for tracked vehicles,” and a huge crater in the road from Sonsbeck to Veen. Lt-Col Wigle ordered C Company to dismount from their Kangaroos and advance on foot. At 1600 hours, with the crater filled, the battle group advanced until stopped “by very heavy machine gun fire, mortar concentrations and SP [self-propelled guns] fire.” It proved “too much” for them to handle. One tank was brewed up as was a Kangaroo. Wigle went forward at 1800 hours and returned at 1900. Bde ordered him “to capture Veen before first light.” C Company had six wounded in the late afternoon/early evening; there were also two casualties in the Pioneer Platoon.

The CO called an orders group; he had decided upon a night-time infiltration with B and D Companies. The night was dark, the route not reconnoitred, there was no tank support and limited artillery support, the infiltration would follow a creeping barrage (difficult with experienced, well-trained troops and problematic with companies composed largely of recent reinforcements, the outer and inner defences were well fortified, the enemy (paratroopers) was well equipped and determined, and the communications between the companies and tactical headquarters sporadic.

The companies crossed the start line at 0100 hours on the 7th. Coordination with the creeping barrage proved thorny; D Company had casualties from friendly fire, including one Argyll killed, and in the confusion, elements from D Company became mixed up with B. In time, B’s 18-set broke down and Capt Leonard Perry had no communication with Lt-Col Wigle. For his part, Wigle could not determine the locations of either company in the ensuing hours. The night was as “black as shit,” as Pte Peter Leslie Ginn from Newfoundland later told his son. One of B’s three platoons became lost; one platoon (possibly just a section of a platoon) from D lost contact. Argylls from both companies stumbled into Germans in the dark (some Germans were captured and vice versa).

“I could see guys laying across in the field”

At one critical juncture, the two company commanders conferred. Capt Sam Chapman considered the situation hopeless (and had thought as much at the orders group) and suggested they ask for permission to withdraw; Capt Perry wanted to press the attack. In the end, they went their separate ways. Chapman received permission and pulled D Company out. Perry went ahead with his two platoons and no means of communication save runners. At the breaking of first light, B occupied German trenches; the enemy pulled back. They faced a large, heavily-defended building. At one point, Perry (almost certainly in a state of battle exhaustion) charged across the open ground. It failed; they took casualties and fell back. At dawn, the outnumbered, out-gunned Argylls surrendered. Pte Ken Brimacombe of 10 Platoon, B Company, never forgot the sight:

“… after we surrendered, and we were climbing out of the trench or we could get our heads up and look. I looked back and I could see guys laying across in the field, I guess they were dead. Maybe they weren’t all dead. Maybe some of them were still Alive; but I could see these forms ’cause it was a fairly flat field for quite a good ways back …”

About two months later, Sam Chapman told his wife that “I saw them lying all over the place … God but I’m glad it’s over.” He was “very low.” “It’s the only time that I can recall,” he said, “that I would have almost been relieved to be killed … I was just interested in doing what I … had to do and trying to keep as many people alive as I could.”

“a terrible mistake”

Fifty-one Argylls were killed, wounded and/or captured in the hours between 0100 and about 0700 on the 7th. Of that number, only 2 had been with the unit before 9 September 1944; 17 joined as reinforcements between 9 September and 29 November; and 32 were taken on strength between 9 January and 7 March (most arrived in February, many in late February/early March). Pte Smith’s situation, as a very recent reinforcement, was by no means unique; 24 of them joined the unit between 28 February and 7 March. Pte Smith had more experience than most. Of the 51, 22 were from B Coy; 21 from D; and 8 from other companies: 6 from C Coy and 2 from Support. It is unclear how Argylls from C Company, including Pte Smith, ended up with B and D Companies for the attack but they did. The two Argylls from Support Company also present a mystery; there is no record that anyone from the mortar, anti-tank, carrier, or pioneer platoons was part of the action. Confusion was the order of the day, a day that ended in failure. In reminiscence, Capt Claude Bissell, the Adjutant, recalled:

“After the failed attack on Veen, he [Lt-Col Wigle] said to me, ‘Claude, I made a terrible mistake.’ Then he slumped forward asleep.”

“what a sad futile loss of life had taken place”

Maj Hugh Maclean once remarked that of all the defining characteristics of an infantry battalion in battle, “leadership matters too – most of all, no doubt.” Lt-Col Wigle had been in command for barely six weeks. He was, as Maj Bert Coffin, acting CO of the South Alberta Regiment, expressed it:

“a divisional staff officer with no battle experience and no field command experience … Being a staff officer, he thought divisional orders were simply obeyed. Experienced officers, however, made such orders work on their own terms.”

After the battle in the Hochwald Gap, Capt Perry was, as Lt Herb Maxwell put it, “in a dreadful state. He really was in a dreadful state.” It is likely that Len Perry had battle exhaustion. About 20 years after the war, Perry returned to Veen:

“As I looked at the lovely little brook, which I had last seen as an anti tank Ditch filled with barbed wire, and the peaceful cottages and farm buildings, I could not help thinking what a sad futile loss of life had taken place.”

In battle, mistakes are costly. The Argylls killed that day joined what Capt Bissell called “the shadowy company of the dead.” It was commanded by the unit’s beloved padre, H/Capt Charlie Maclean who saw to their burials with a piper playing “Flowers of the Forest.”

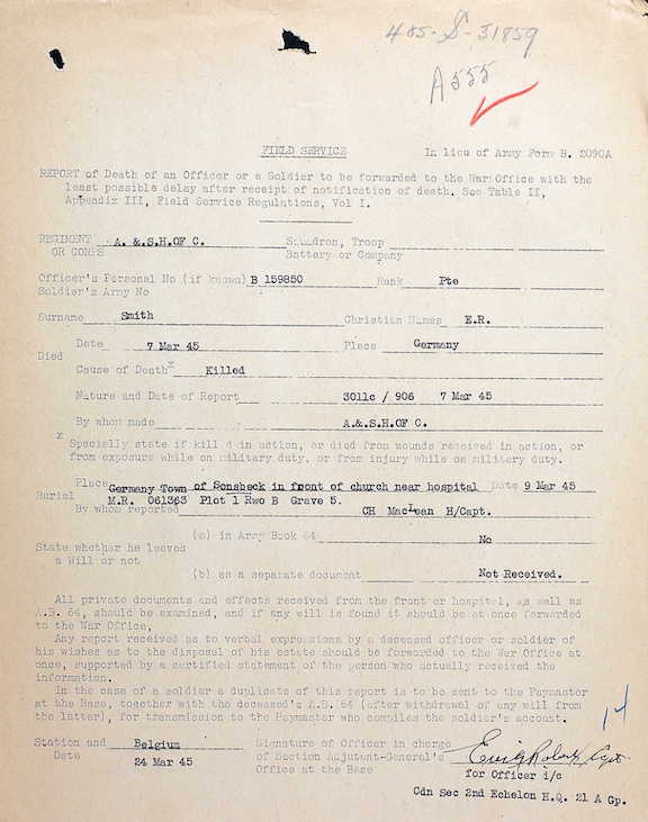

Field Service form for Pte Smith, made out by HCapt C. H. Maclean, the Argylls’ padre.

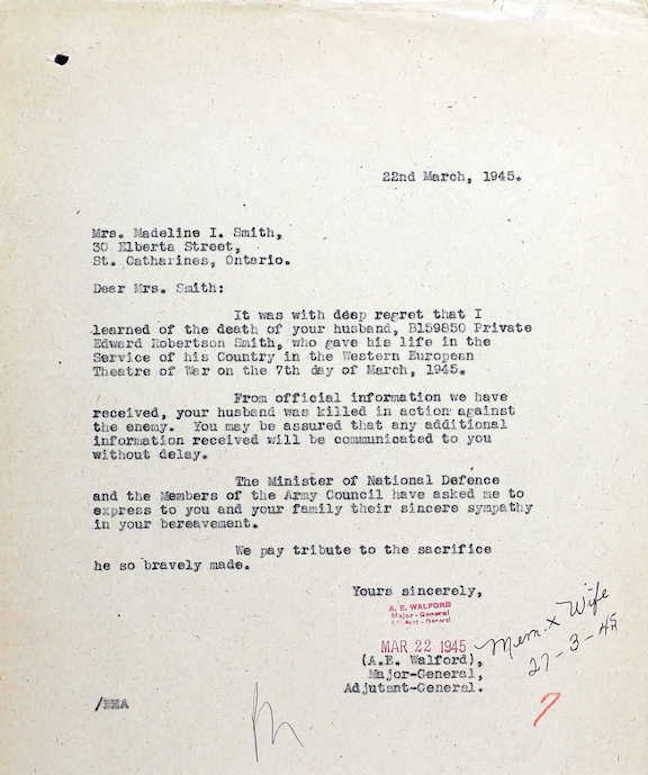

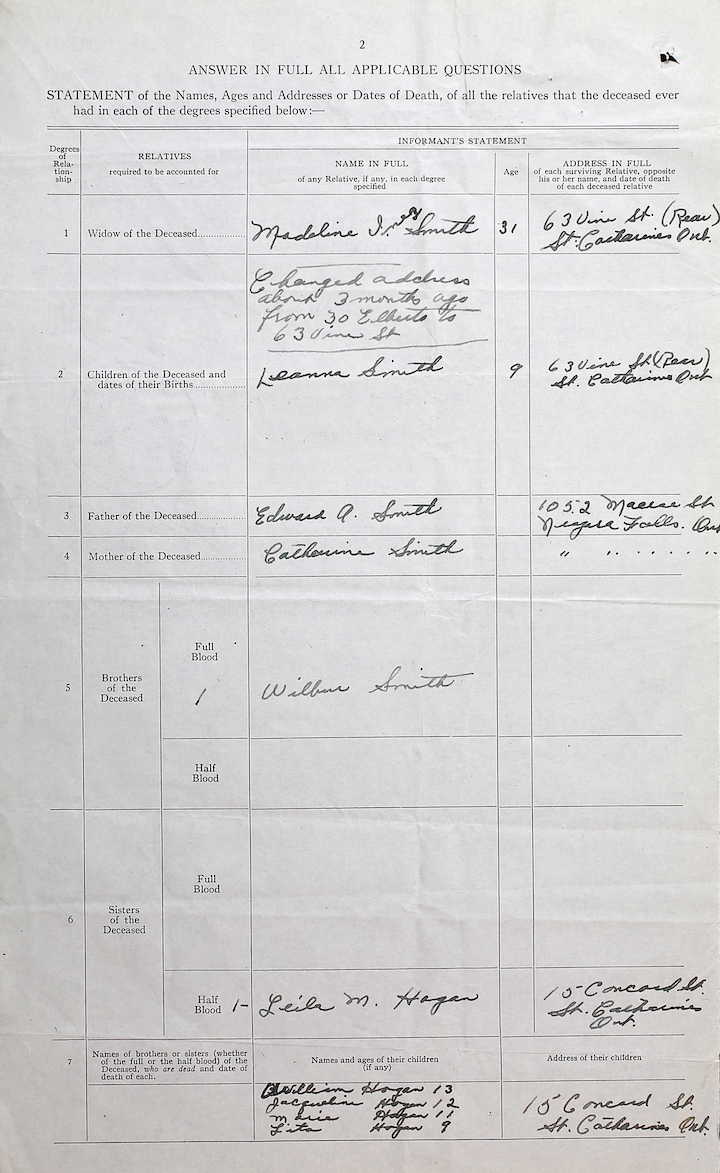

Madeline Smith received a letter dated 22 March informing her of her husband’s death. There was the administration of his estate, which required handling and her minister witnessed the proper forms. He left little by way of personal effects: a few souvenir coins, a wallet, an unemployment insurance card, a “Legion” card, a “Union” card, and a “Vehicle Operators License.” In 1945, Madeline noted that “My husband has one brother [Wilbur Smith] who has been sick for years + has been in the asylum in Hamilton.” Edward’s father was still alive, “Superintendent of Mail Carriers,” and still living in Niagara Falls.

Letter from Adjutant General to Mrs Madeline I. Smith, 22 March 1945.

“first coloured McKinnon employee to give his life in this war”

McKinnon’s took note of his death – the “first coloured McKinnon employee to give his life in this war.” Madeline Smith died at the age of 34 in St Catharines on 2 April 1948; her daughter was 13. Leanna Smith married in Niagara Falls about 1952; she had three daughters, two of whom predeceased her. She died in St Catharines on 1 April 2010. One of Pte Smith’s great-grandsons served with the Canadian Armed Forces and has taken note of his grandfather’s service and sacrifice.

Between 1 March and 7 March 1945, 15 Argylls were killed in action, 32 wounded, and 32 POWs.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Remembered respectfully – An Argyll

Note: Pte Smith’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Edward Robertson Smith

Family of Pte Edward Robertson Smith.

Aerial view of McKinnon Industries, St Catharines, date unkown.

Welland Avenue United Church, St Catharines.

Map of the Hochwald Gap by Maj Hugh N. Maclean.

German dead, 26 February 1945.

German SP (probably a 75mm) at the edge of the gap. Another tracked vehicle is visible in the trees to the right.

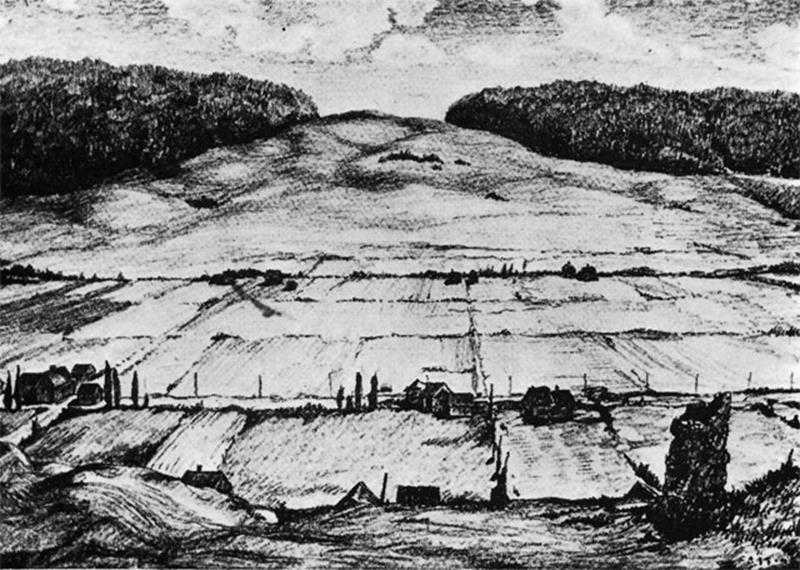

The Hochwald Gap, drawn by Brigadier G. L. Cassidy, DSO, ED, based on sketches made on the spot.

Argylls moving forward to Veen, 6 March 1945.

Argyll vehicles skirting Sonsbeck, 6 March 1945. Pte Gordon Penrose, a stretcher-bearer, is standing in the middle carrier facing the camera.

Argylls on Kangaroo, 11 April 1945, Germany.

Obituary, Pte Edward Robertson Smith.

Gravestone of Pte Edward R. Smith, Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.