Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

In the early days of the Black yesterdays project, I learned of Piper McDonald. He was mentioned by fellow bandsmen such as Bill Miller, Murdo Miller, Andy Scott, Jim Patterson, and Earl Wardell. If that were not enough, the late CWO J.B. McQueen, the late CWO Archie Cairns, and the late Pipe Major Emeritus John Terence all ensured that he would not be forgotten.

When Earl Wardell died, CWO Norm Wills, CD, and the Argyll Regimental Association purchased an Argyll Poppy in memory of Earl. The group decided to commemorate Piper McDonald, a friend and wartime comrade-in-arms of Earl’s. It is a presumption to write that their resolution would have pleased Earl, but I am certain it would.

Earl Wardell was a longtime friend. His fellow drummer was Jim Patterson, father of my best friend from the age of 4 and throughout high school and university. Like Earl, Jim Patterson was a lovely man who became deputy chief of police in Hamilton. I have written this biography with them in mind as well as all of the pipers and drummers listed above. I have attempted to set Piper McDonald’s life within the context of the Pipes and Drums from 1940 to those first weeks of August 1944 when young McDonald was killed. The P & D’s importance to the Regiment’s “style,” as Maj Hugh Maclean would have it, was critical and deemed such from the first days of mobilization.

I offer my thanks again to Ben Dyment, Archives Technician, Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board Educational Archives, for his help on this biography. Pipe Major Scott Balinson and Drum Major Kent Wilson have been friends for decades (a young MCpl Wilson made me his personal charge on a Meaford exercise in the early 1990s; I have always been appreciative of his forbearance), and their support is always there. PSgt Conor Cooper helped with an image of Piper McDonald, with the armouries being off-limits to non-serving persons during the pandemic-related closures.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Richard McDonald (1922–44) (B 45713) 1st Bn Argylls

KIA 10 August 1944

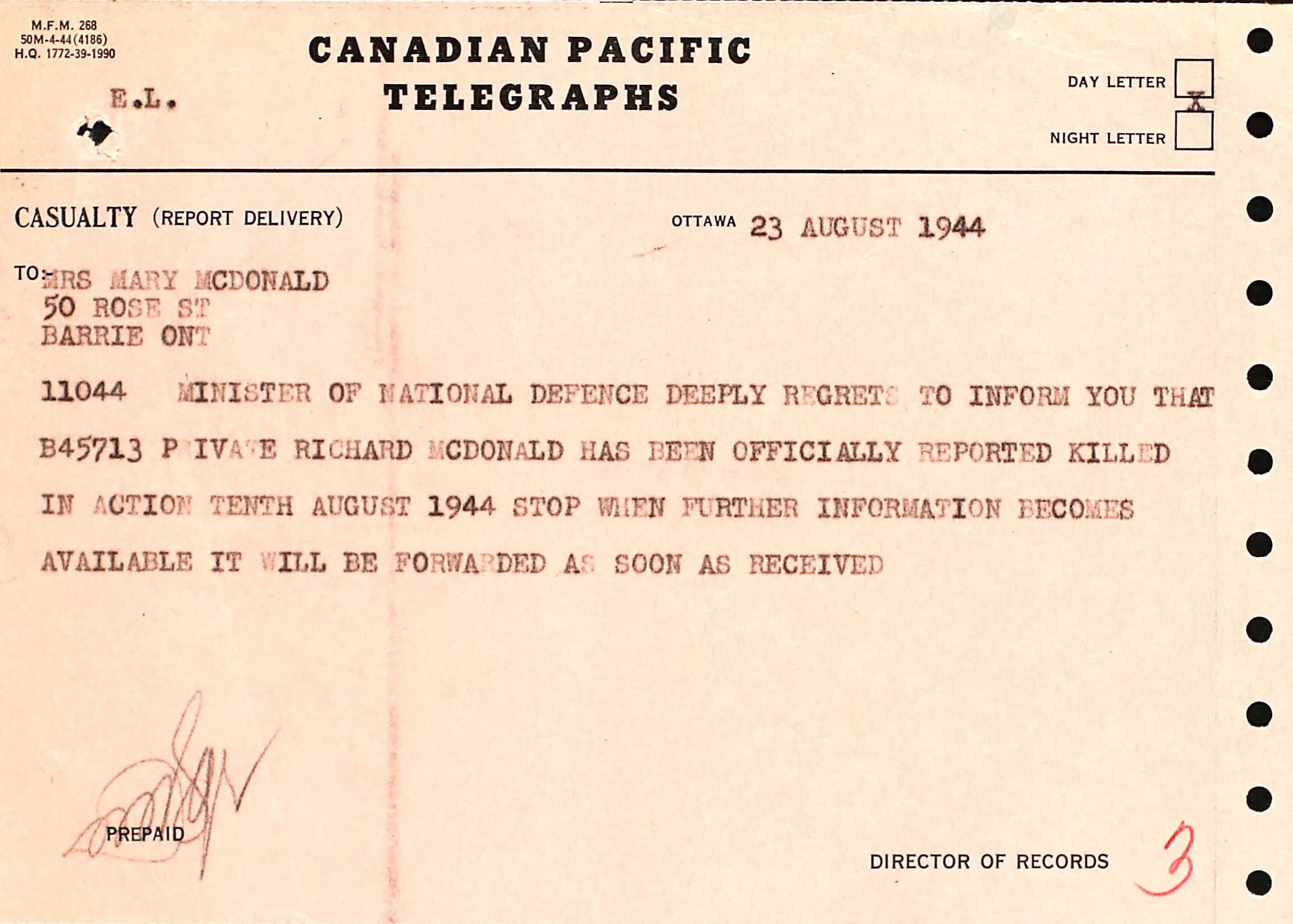

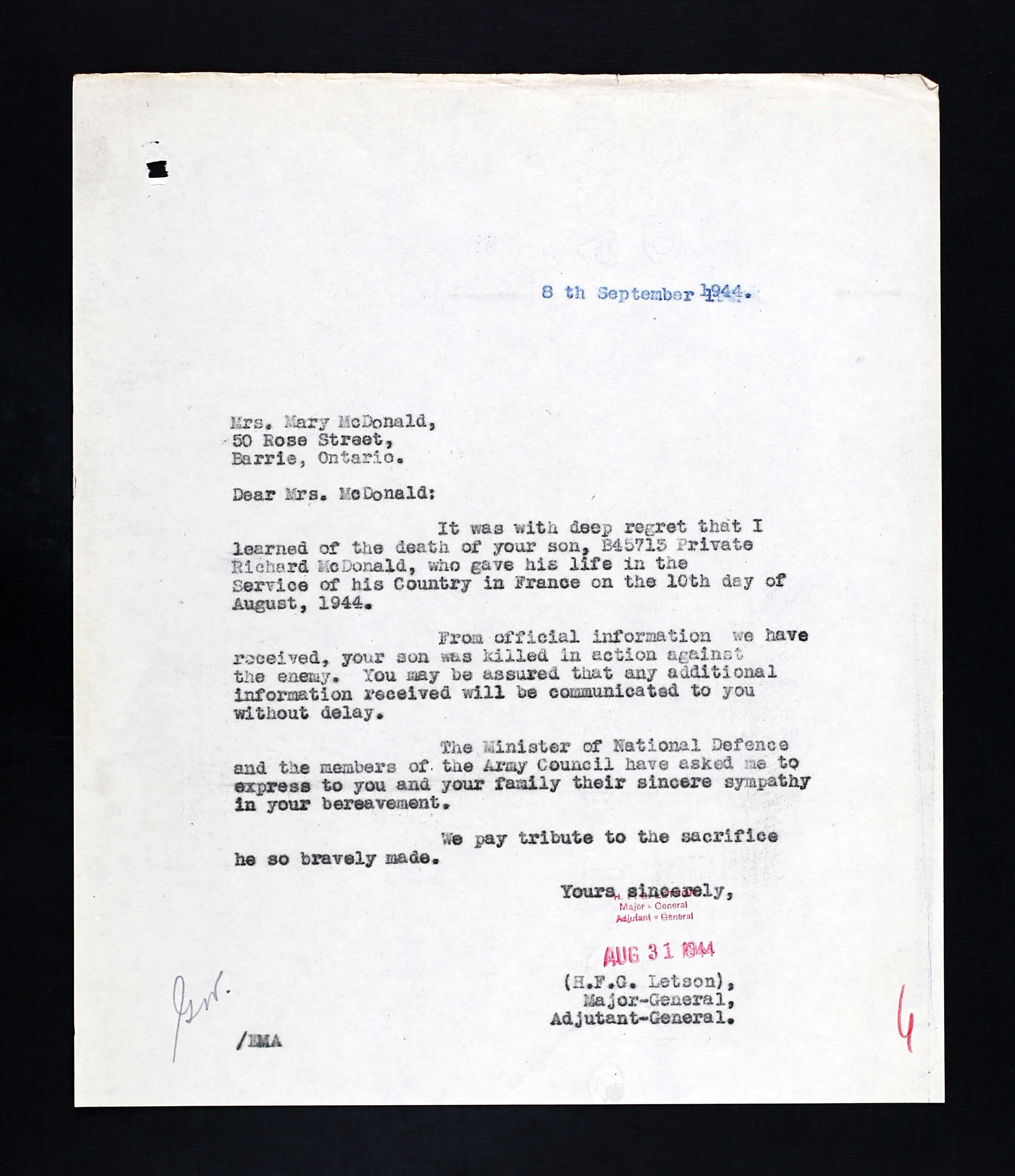

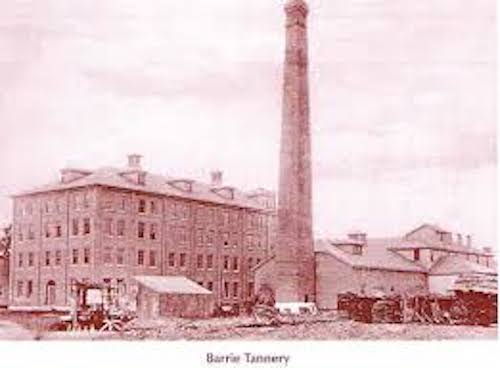

Richard McDonald was born in Dumfries, Scotland, on 15 October 1922, the eldest of the six children of Robert (d. 1958) and Mary McDonald; they had married in Scotland on 7 November 1921. Robert McDonald was a First War veteran, having served with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. The family immigrated to Canada in 1926 as “assisted [subsidized]” immigrants; they left Glasgow, Scotland, on the S.S. Athenia, arriving in Quebec on 7 June. The family settled in Hamilton, where Dick (as he was known) attended Peace Memorial School on E36th Street on the Mountain; they lived at 102 E34th Street. They moved to Barrie in 1937 and lived at 8 Wood Street in Allandale (now part of Barrie) before moving to 50 Rose Street in Barrie after Richard’s enlistment. Robert McDonald was a “brass grinder.” Dick had a grade 8 education at an “urban” school and left when he was 14 because he had “to help family and was tired of school.” His school record reads: “1-9-37 … Pro[moted]. – near Orillia.” He worked as a “market gardener at home and for others” for five years, earning $8 weekly, and then for two months in 1939 in a lumber and coal yard, where he earned $10 weekly. McDonald worked at Clarke & Clarke, sheepskin tannery, where he had served, but did not finish, one year’s apprenticeship as a dyer (another source in his personnel file states it was nine months); he earned $18 weekly.

The Argylls mobilized in June 1940 and Dick McDonald enlisted on 5 July 1940 in Hamilton. He was 5’, 7½”, 118 lbs., with a “dark” complexion and brown hair and eyes. His employer promised to take him back again after his discharge from the army, a promise that accorded with McDonald’s post-war plans. He had no farming experience and no other plans for employment after the war. Upon enlistment, he assigned $25 monthly to his mother. For Highland regiments in Canada, and the Argylls were no exception, kilts and bagpipes were icons. For the 1st Battalion, the Pipes and Drums were the foremost embodiment of these great symbols; they personified the unit, they set it apart from most other infantry battalions, they infused every aspect of battalion life, and they aided in the building of morale and unit cohesion. For four years, Piper Dick McDonald lived his life within the framework of the duties attached to a Regimental piper.

“we heard the Pipes and Drums … and as soon as we heard that we signed up … the music”

Pte Jake Leyland and his friend, Bill Wood, went to the James Street Armouries in Hamilton in 1938, where “we heard the Pipes and Drums … We went in and as soon as we heard that we signed up … that hit us right off the bat, was the music.” The peacetime regiment had two bands: the Pipes and Drums, and the Bugle Band. Lt-Col Thomas William Greenfield, the commanding officer in 1940, called a meeting of his officers on 17 June 1940. The unit’s status had changed “by reason of its having been mobilized” as part of the Canadian Active Service Force (CASF). There were important matters to be considered, and the bands were one of them. “There was no provision for two bands on the C.A.S.F. unit strength”; thus, the Brass Band would be left behind. The CASF establishment for “Scottish Battalions provide[d] for one Sergeant Piper and five pipers, additional pipers may be carried as stretcher bearers etc.” Piper Bill Miller remembered that the “originals that were in the band, they all come from the militia” and the drummers were often buglers as well.

“never seen a pipe band before … it was … really something”

Pipe Major Peter Caithness McGinlay was, Miller declared, “our godfather, as far as the band was concerned.” When McGinlay became Regimental Sergeant-Major in 1940, Frank Noble took over the band but, as Miller declared, “then he’d [McGinlay] protect us … Nobody could lay a finger on the Pipe Band.” At Niagara Camp on 6 August 1940, the “Regimental Pipe Band began to follow the British tradition of ‘Beating Retreat’ on Tuesdays and Thursdays.” Pte Gord Boulton had “never seen a pipe band before … it was … really something.” On 14 September, the Argylls participated in a brigade parade and the “troops strode freely … keeping in perfect rhythm to the strains of their pipe band.” On 11 October, the band attended “the unveiling of an additional monument there [near the Brock Monument at Queenston], this one in commemoration of those Indian allies who lost their lives assisting General Brock repel the foe [in 1812].” The band, Lt Don Seldon noted, “made its customary good impression.” On 10 November 1940, the Regiment deposited its Colours at Central Presbyterian Church, the Regimental church, for the duration of the war. Pte McDonald went AWOL in November 1940 from Camp Niagara and was confined to barracks for five days.

“martial music of the pipes”

In British Columbia in July 1941, the band led the battalion for the last leg of its march from Victoria back to Camp Nanaimo After a few months in British Columbia, the unit returned to Ontario before departing for garrison duty in Kingston, Jamaica. On 2 September 1941, the main body embarked on RMS Lady Drake for the voyage. Pipe Major Noble confided to his diary: “I have to try to be like Peter [McGinlay] + give to the utmost of my ability the same type of leadership I expected from him to my own boys + they are fine lads too.” Each afternoon, the band played from 1600 to 1700 hours. The Argylls’ new CO, Lt-Col Ian Sinclair, remarked that it was “damned fine pipe-music.” Noble noted that the “heat has taken its toll on our pipes already.” In Kingston at Up Park Camp, the battalion guarded the internment camp, handled ship inspections, and, later, moved the companies through training at Newcastle in the mountains. At 0900 hours daily, the Pipe Band “escorted” the camp guards to their quarters. The war diarist wrote approvingly of the impact made by the “martial music of the pipes.” The band played Retreat on the camp’s cricket ground on Tuesdays and “before the City Cenotaph [in Kingston] on Thursdays.

“very remeniscent [sic] of soldiering in ‘Kipling’s’ British India”

It was, Piper Dick Gillespie thought:

“very remeniscent [sic] of soldiering in ‘Kipling’s’ British India. Everything was done in the British garrison manner, from reveille to lights out. For the pipe band this meant turnout to play reveille at 6:30 A.M. The bugles would sound the Regimental call, at which point the pipes & drums would strike up the traditional ‘Johnie [sic] Cope’, and march through the Company lines … Our next duty was guard mount, the band arriving at the Parade Square at 8:30 A.M.…

On completion of the inspection, the band played the new guard over to the Internment Camp & played the old guard back, completing the duty about 10:15 A.M., at which time we’d have an hour or so of band practice, then a dip in the pool prior to lunch. Most of our afternoons were free, except for Wednesdays, or other days when we were required to play at some function, military or otherwise.

We trained under the Medical Officer [Adrian Yaffe] from 2-4 P.M. (as the band fuctioned [sic] as stretcher bearers in action), then off to choir practice at the church. – – The Padre [Dykes] wanted a choir for his Garrison Church, so who better to detail than the musicians of the Regiment. The Padre had his moments of exasperation with us, it’s difficult to teach a group of Scottish Presbyterians the Church of England chants.

We played Ceremonial Retreat on the cricket pitch twice weekly, an event attended by both the military and the local populous. Apart from our operation as a band, we were on a roster for Duty Piper & Duty Drummer (bugler). On the morning of duty you proceeded to the officers lines & played Reveille, then you played the subsequent meal pipes at the other ranks mess “Brose & Butter”. 10.00 A.M. you played the defaulters from the guardhouse to the Orderly Room to the tune of “A man’s a man for aw that”. In the evening the Duty Piper played a program at the Officer’s Mess, while the Officer’s [sic] dined, at the conclusion the Colnel [sic] would offer the piper a drink and in return the piper would toast the Regiment. The Duty Pipers [sic] day would end with the playing of Lights Out, through the Company lines, “The Weary Maid.”

“a ghastly thundering and wailing”

The band and its sounds were ubiquitous and not always subject to praise. Sgt W.R. O’Connor opined ruefully in a battalion publication that “life should never begin before noon.” In the army, however, he noted that the “horrors of an early awakening are brought home with striking reality. For centuries the army has been subjected to a hideous custom known as Reveille—.” Within a Highland battalion, reveille held two terrifying incarnations, which O’Connor described in detail:

– – You’re a buck private, fast asleep, exhausted by the previous day’s hardships. Z-z-z-z-z – you are dreaming contentedly of green forests, a dark mysterious pool, and one or two swans gliding placidly among the water lilies. You are happy. This is the time when you expect a haunting melody, played upon a harp or a flute, to come stealing softly through your dream, soothing and caressing your senses. But what actually happens – –? Bla-a-a-a! Bla-a-a-a! A bugle greets the sarcastic crack of dawn. Reveille!

You are Irish though, and therefore stubborn. You’re still asleep, and are not to be beaten this easily. A troubled frown passes over your face, but gradually it becomes composed once more, as the bugle notes die away, and you struggle to collect the remnants of that wonderful dream.

But the army is stubborn too. Long years of experience have taught it many lessons, and it knows this business of Reveille quite well. You’re given about twenty seconds of peace before a new device of the devil is brought to bear upon you.

The twenty second period of grace passes just as quickly as twenty seconds will, and then a ghastly thundering and wailing penetrate the fog as the pipe band commences to play Reveille. Through the haze you hear Pipe Major Noble shout

“Beat it out, Alfie!” And Alfie Bale, the bass drummer does just that. Fired by the enthusiasm of the pipers and the encouragement of the pipe major, he twirls his sticks and pounds his drum with devilish glee.

“pipe band looking verra bonnie in their kilts and sporrans”

In another issue of the same publication, O’Connor considered the social dimension added to battalion life by the Pipes and Drums. He asked, “Do you know what the troops at Up Park Camp really go for?” and provided the answer “– – Regimental Dances!” They were, he suggested, “one of those things which help to make a soldier’s life less weary.”

It was indeed a sumptuous spectacle:– – lovely ladies in the most colourful evening gowns; the officers and pipe band looking verra bonnie in their kilts and sporrans; the skirl o’ the pipes, the flash of the drum sticks; (Did someone say: “Yes, and the clinking of the glasses” – – ?)

We danced to everything from “La Conga” to the stately “Blue Danube.” Entertainment of a truly Scotch nature was provided when some of the officers, men, and their ladies danced a “Reel o’ Tulloch of rus.” A vivid sight indeed…

Such occasions offered their own tangible rewards. Drummer Earl Wardell recalled:

… On New Year’s, one time [Pte] Jimmy Patterson and myself and the buglers and the drummers of the Pipe Band, we had our own section. Like the pipers were up in one hut and attached to that was the drummers … Well, you were pretty close, anyway. I remember one New Year’s Eve we actually got a bottle of Canadian Club out and drank out of our mugs, and that was quite an experience…

“Oh yes, we did a lot of field training”

Piper Murdo Miller recalled:

Oh yes, we did a lot of field training.

… We knew it was common practice that bandsmen were stretcher bearers and company pipers were the runners of the Regiment. And the rest of us were just stretcher bearers, which isn’t the best job going…

Military training had its effect on the ceremonial duties of the band. On 8 May 1942, the war diarist observed that:

As a greater part of the band is training, Retreat is now played only once a week. On such occasions the cricket field is lined with spectators, who never seem to tire of the ceremonial, or the wild sweet music of the pipes. It may be sacrilege to add that the same feeling does not prevail among the men in close proximity to the pipers’ hut…

Pte McDonald qualified as a “Bandsmen Group C” on 1 June 1942 in Jamaica; the latter brought a pay increase from $1.50 “Regimental Pay” daily to $1.75 “Tradesmen’s Pay.” He was now a Regimental piper.

“Thus is kept alive the tradition and glory of the Scots”

The band was integral to the idea of the battalion as a Highland one. On 30 September, the war diarist Lt R.D. “Peter” MacKenzie ruminated on the band’s critical importance to the Argylls:

…With Scottish Regiments have always been associated courage, valour and an invincible aggressiveness. In a country such as Jamaica it is an easy matter to forget or regard as secondary, the background of which we should be most proud. Therefore the preservation of that background falls largely upon the able shoulders of our bandsmen.

Duty Buglers and Pipers wear the kilt. The Band similarly attired, add that mysterious something to the daily guard changes. On Friday of each week the colourful spectacle of Retreat is solemnized on the Cricket field. This attracts many civilians, but the majority of spectators are from the men of this Regiment.

The evening meal at the Officers’ Mess, particularly on “Guest Night” is one to be long remembered. On this occasion the Pipe Major assisted by two or more of his Pipers plays a series of Scottish airs among which is the favourite of the guests or the Commanding Officer. The “Regimental” — “The Campbells are Coming”, completes the program. On ordinary days these duties are performed by Piper of the day.

Thus is kept alive the tradition and glory of the Scots; thus are we different in many respects to regiments whose men are chosen from the same source as ours. That difference we shall maintain, and perhaps someday merit another honour for our kilt.

McDonald qualified on the St. John’s Ambulance course in September 1942. On 9 October, the war diarist remarked:

…Now that the members of the Band have qualified for the St. John’s Ambulance Certificate, each is taking two weeks training and gaining practical experience in the R.A.P.

Piper Murdo Miller explained that we “knew it was common practice that bandsmen were stretcher bearers and coy pipers were the runners of the regiment. And the rest of us were just stretcher bearers, which wasn’t the best job going.” Drummer Jim Patterson remembered that “we had to take a St. John/s Ambulance course and pass that as stretcher bearers and aid men, patching up wounds and broken bones and so on.”

The battalion embarked on a two-week trip around the island in late October/early November 1942, and the band played a conspicuous part. “The natives,” the war diarist declared, “were fascinated by the music of the pipes and gazed in bewilderment at the kilted pipers, their uniforms and instruments…” Piper Richard Gillespie remembered that it “was quite a sensation [for] the local populace to see Scottish pipers dressed up in kilt and playing bagpipes … they sort of began to feel the music and they’d start swaying.” The Jamaican military band also attended “in its colourful Zouave uniforms.”

“they were beyond drunk”

Drummer Earl Wardell asserted that “the pipe band was always known as the gentlemen of the regiment.” McDonald’s so-called ‘crime sheet’ was a short one. On 11 March 1943 Capt Bob Paterson, the adjutant, “Admonished” McDonald for his “lst Offence” for “Drunkenness.” Five days later, Paterson confined him to barracks for 5 days after RSM McGinlay reported that McDonald “acted improperly during kit inspection.” Wardell recalled the circumstances of McDonald’s admonition. The battalion showed training films at the Carib theatre in Kingston; it was “a lovely, big modern theatre” as Drummer Patterson remembered it:

If you didn’t want to go to the theatre, [you’d] go into the Carib pub, which happened. A very good friend of mine, Dick McDonald, was one of the pipers, and Andy Scott I think is the other. We used to play whatever coy was going down to see this film, a couple of pipers would play them down and back, maybe a mile and a half or so. But anyway, I guess they’d had a shot of the film before and they didn’t want to be bothered with it this day, so they stayed outside while the others went in to watch the picture. And somehow I guess they just strayed away to the Club Carib, the pub. And you should’ve seen them come back … Oh, they were beyond drunk …”

As Patterson explained, “the Carib bar was just another bar, it was a well-run bar, clean … a hangout for the [men].”

“His hobby is playing the bagpipe”

The Argylls returned to Canada and Camp Niagara in late May 1943. In the few weeks before heading overseas, there were interviews, medical inspections, leaves, marriages, and the arrival of reinforcements from Camp Shilo (see Pte Lyall Wright Wotton).” All soldiers suitable for overseas service were interviewed. A qualified “rifleman and piper in band,” McDonald was deemed a:

… small young man of neat appearance and above average intelligence. He plays soccer and is interested in other games. His hobby is playing the bagpipes and he is now a piper in his battalion’s pipe band. He drinks very moderately and smokes heavily. He is a single young man who appears to be steely and reliable and should prove to be excellent soldier material.

The army examiner recommended him for “Inf. ® Piper. Non-tradesman.”

“there wasn’t anybody that wasn’t like a family”

On 13 June 1943, the battalion held a “drumhead service” on the polo field and hosted civic representatives from Hamilton. The war diarist recorded that the “familiar skirl of the pipes … was a thrilling climax to the ceremony yesterday in which the city of Hamilton extended official welcome to Officers and men of the 1st Battalion of this proud old Highland regiment.” There were losses as the men too old for overseas service or with medical conditions were taken off strength. The Pipes and Drums felt the loss as well. Seven officers and 120 men left by boat at 1100 hours on 14 June. The battalion formed up and the “Regimental pipers were present and when the draft moved away, the pipes played ‘Bonnie Charlie’ [a tune often called ‘Will Ye No Come Back Again’].” Dick McDonald lost one of his good friends with this draft – Drummer Earl Wardell, who had a hernia and stayed behind for an operation. For Wardell it was:

terrible … after the two-year stint in Jamaica there wasn’t anybody that wasn’t like a family … you had respect for everybody that had rank and you almost loved everybody you were with … I can recall sitting in the kitchen [in Hamilton] and crying, actually really crying, I couldn’t believe that I wasn’t going to go with all these guys that I’d been with for so long.

In July, the battalion entrained for Sussex Camp in New Brunswick, where it waited to go overseas. The “unit … [was] ready to march” on 20 July and the “troops fell in on the parade square at 2000 hours in marching order and moved off in column of route at 2013 hours.” As always, the “Pipe band led the unit from Camp, as the ‘Black Bear’ was played, the men cheered lustily on the march.”

“shades of Jamaica days where the Pipe Band had played an important part in Regimental affairs”

The months in the United Kingdom witnessed moves to and from different training camps, an increased tempo of training at the collective level (platoon, company, battalion, brigade, and division), new equipment, and a new CO, Lt-Col J. David Stewart. It represented a different tempo and altered rhythm for the band, and a lesser prominence. On 19 November 1943 at Uckfield, the war diarist took note of the change:

The Pipe Band hits the headlines today. Playing retreat for the first time since our arrival in England. The colorful spectacle was held behind St. Michael’s College at 1620 hours and greeted enthusiastically by the townspeople. To many of the Regiment it must have brought back shades of Jamaica days where the Pipe Band had played an important part in Regimental affairs.

In December Lt-Col Stewart suggested the battalion hold a Christmas party for the children of the nearby Heritage Craft School and Hospital. “In many cases,” children were unable to attend, “the party was taken to them” with the “Pipe Band in attendance.” The band “played in and about the wards much to the enjoyment of the children.” He was AWOL from 3 to 7 December 1943; Maj Art Hay, the deputy commanding officer, ordered that he forfeit 28 days’ pay; he also lost “one Good Conduct Badge.” McDonald lost pay but nothing more. The band was also featured in unit and company celebrations of the Christmas season, and as a Regimental piper, he participated.

“Inf Stretcher-bearer”

Argylls were interviewed again in the early months of 1944; McDonald took his turn on the 14 February. He was now 5’, 8½” inches and 140 lbs. He enjoyed skating and hunting and played soccer (full back). There is a segment of the form devoted to “Ability to Entertain: Music” followed by categories arranged by instrument, “vocal,” “theatrical,” or “other.” The examiner wrote “Bagpipes” beside “Woodwind,” which is correct. He had 5 “minor offences,” resulting in 20 days confined to barracks. His previous duties with the battalion were summarized succinctly: “Regtl duties; Mil Trg”; current duties were listed as “Regtl Piper” and, as for type of service “desired,” it was “Inf Stretcher-bearer.” In his remarks, Capt C.P. Haynes wrote:

Small physique, pleasant straight-forward manner of speech. Slightly above average ability to learn with some mechanical aptitude. Seems quite bright and direct in his responses and of normal stability. No outstanding leadership characteristics and would appear quite dependable and self-reliant for years.

As for a recommendation for possible employment, Haynes noted, “Suitably employed.”

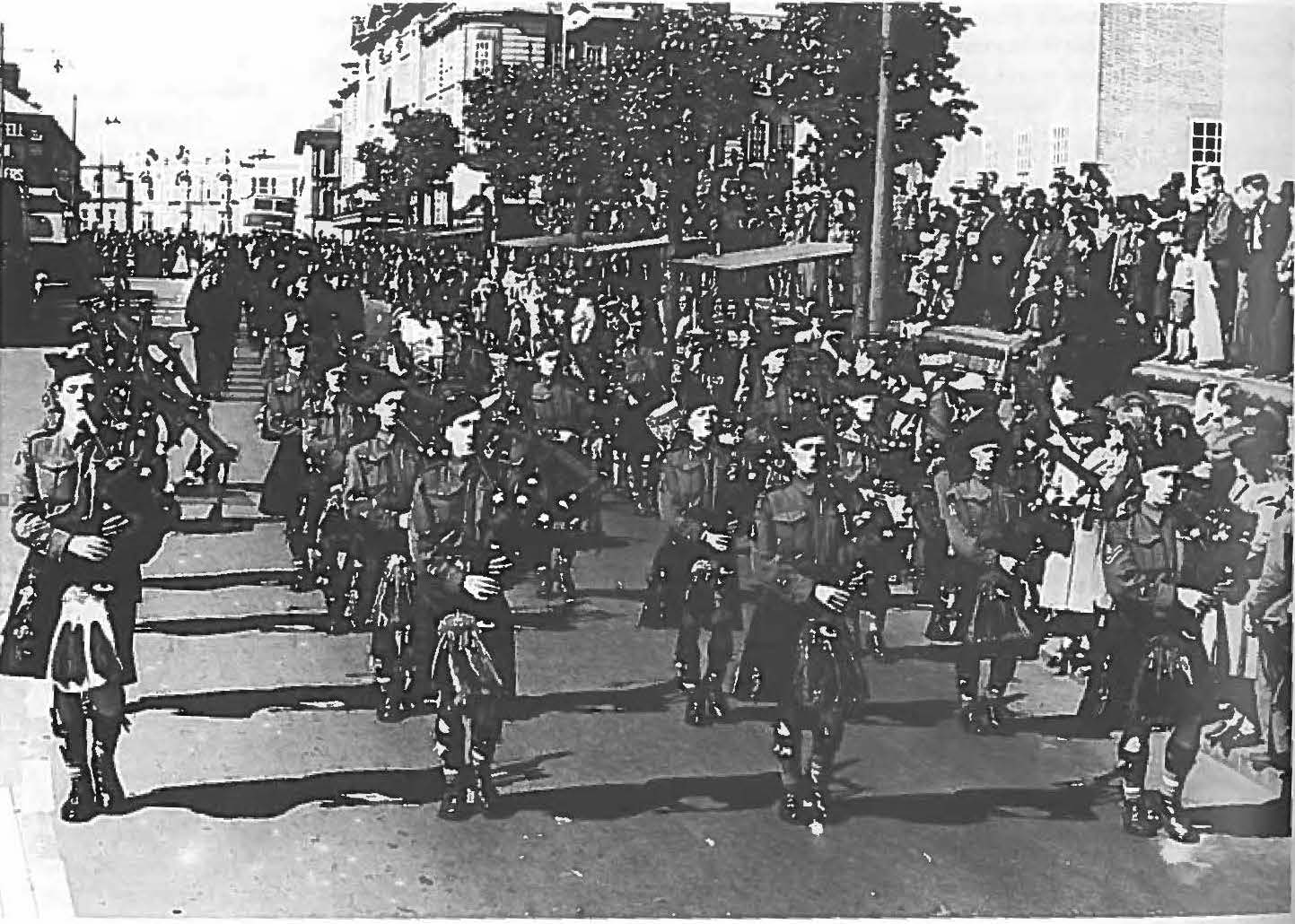

The band was prominent in the various inspections by dignitaries in the winter/spring of 1944. In March it readied itself for “Army Week” – “the signal distinction but perhaps dubious pleasure of representing the Argylls in the parade in London.” On the 27th, the “Argyll pipe band” along with 150 “other ranks” participated in the “Salute the Soldier” parade. There were several saluting bases, including one for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The Argylls were “one of the two Canadian units present” and the band was “as smart as usual and received much applause.”

The Argylls’ Pipes and Drums, Salute the Soldier Parade, Tunbridge Wells, UK. May 1944. Piper McDonald is the second from the right.

“a profound shock that a fight was, after all, on the cards”

In the final months before the invasion, Maj Hugh Maclean wrote:

From this time on the tempo of training and of life itself, imperceptibly at first, then consciously, quickened. The invasion, previously hardly more than a far-off idea, slowly acquired reality and took on increasing importance in men’s minds. Gradually the Battalion became aware that it was going to fight; actually and even after all the preparations and the almost subconscious knowledge of that eventual necessity, it still came as a profound shock that a fight was, after all, on the cards.

Piper McDonald embarked for France on 21 July 1944 and disembarked two days later. The “fight” quickly became a reality. Pte George McGowan was wounded on the 25th, the first Argyll casualty of combat. Between then and 9 August (the day before McDonald was killed), 37 Argylls were killed in action, 85 were wounded, and 1 was captured for a total of 123, all but 4 of them in the week from 2 August to the 9th. After a few days of “having been shelled, mortared, staffed by aircrafts + also having been sniped at,” Lt Norm Donaldson felt “like a veteran now.” Caen and Bourgébus were “almost a complete shambles.” “Heat, dust and flies bothered us,” LCpl Harry Ruch wrote in his diary, “along with the fact we had no sleep for quite some time.” Battle and its attendant casualties transformed the first-aid training of stretcher bearers into a terrible reality.

“Charlie Richards, he was a piper, and he had the top of his head blown off”

Drummer John Black never forgot the experience and it made an early and searing impression:

… you could put a bandage on fast, and so it would stay on. And we always had adhesive tape in case we couldn’t tie a bandage off… [Pte] Charlie Richards, he was a piper, and he had the top of his head blown off [on 2 August]. And his brain was out of his head, and I put it back in place, put his scalp back in place, and then wrapped the bandage around.

“The stretcher bearers were, generally speaking, some of the bravest of men”

Capt Doug Bryce succeeded Capt Bill Bie as the Argylls’ regimental medical officer (MO or RMO) in November 1944. He reminisced about the MO and the Regimental Aid Post (RAP):

…The RMO and RAP had two or three vehicles. He had a sergeant in charge, a corporal and stretcher bearers … his job in action was to follow the line of attack … to give first treatment to the wounded and to sort out those that should be transferred back as fast as possible and those that could be put off for a few hours. His management of wounds was essentially massive first aid [and] the use of blood and plasma where indicated. When not in action, the RMO was involved more in the general hygiene of the camp, the … [daily] sick parade and the usual daily problems of any group of people … Supplies came up with the regimental medical supplies … I do not recall ever being short of anything, except perhaps in some areas when we were isolated, as in the Hochwald forest action, when there was difficulty in getting supplies up to the RAP because of shelling or bad road conditions in the rear…

The stretcher bearers were, generally speaking, some of the bravest of men … some of them were battle fatigued people who just couldn’t go back to the line, but were used in areas further back from action. There was no way to prepare stretcher bearers for the type of wounds and type of problems they would come across. The majority of the stretcher bearers in an armoured division rode on jeeps and so did their stretchers – and they were exposed to as much fire as anybody else, the difference being that they did not fire back…

In general, when the action was going on the people that came back were either dead or almost dead, in which case there was no particular problem. The wounds that I recall being the most severe were the compound fractures, where we had to use the Thomas’ splints, and the head injuries, which were perhaps the most difficult to get used to … In most cases the medication that was of the greatest use for seriously ill patients was intravenous morphine, of which we had a good supply …

I think dirt, inability to clean and lack of rest were the problems that – aside from the actual wounds – gave us the greatest trouble. Certainly, the so-called battle fatigue was also a great one where many young men who were unable to stand the tension of day-after-day combat would just collapse and become inert and refuse to obey orders or carry out any action whatsoever.

“stop the bleeding and get them the hell outta here”

Pte McDonald was likely attached to D Coy. Other pipers such as Pte Bill Miller were attached to the RAP. He provided a dramatic and vivid picture of the stretcher bearer’s life in battle:

…I was working with the doctor. The stretcher bearers, they patched them up. Of course, everybody carried their own shell dressing and field dressing. It was part of their equipment. And they had their own medical bag and they carried extras, and just mainly would then stop the bleeding and get them the hell outta here … we would take them over to a barn or a house or something like that, and they’d get him back to us [at the RAP] … Mostly at that time [August 1944] they were still carrying them back, and then we had the jeep ambulance from us to the next aid station, and then they had the bigger ambulances, and the doctors had more time, and they had more help.

[At the RAP there was] Bandaging, splinting, that kind of thing. [Dr Bie] Did exactly what we did. It was an absolute waste of a doctor. The Germans used sergeants. Their medical teams … were no higher than sergeants. Their trained doctors were farther back. And it helped, in some cases where a guy was sick, then the doctor could diagnose it there and send him to the hospital or something like that. And it’s a tremendous morale booster, when a guy that’s known me all my life, and I’m the best they’ve got to patch him up when he gets shot? But if it’s a qualified doctor, it was … tremendous.

If it got to the stage where a doctor’s skill was necessary, the guy was in pretty bad shape. Because, as I say, we didn’t have [the equipment to do] anything other than stop the bleeding, give him a shot, record it and get him out. Get him back to a base medical unit as fast as possible. So that, as I say … he [the MO] was a tremendous morale booster and that kind of thing.

…we were … never short [of supplies] … bandages, splints, and a lot of ointments and different things like that. Sulphanilamide had just come out. And not too much else because the whole [supply] trunk was only about two by two by about three feet long … only the Doc and I had the key for it, ’cause that’s where the medicinal brandy was … I was also the cook for them. But we carried a lot of blankets and the stretchers, things like that.

…[At times] you got about ten or twenty casualties wants to get fed, too. But there’s funny things happen when you’re doing that. You try to heat a pot of stew in the back of a truck with a blowtorch. I was stirring the stew and doc was holding the blowtorch. We hit a bump in the road and the blowtorch went flying and set the truck on fire. Took a few blankets to put that out – saved the stew though, saved our lunch. So I was a firm believer: you gotta eat … Last thing in the morning before we moved, make a big thermos jug … full of tea and put the stew in the pot, clamp the lid down…

…tea was just as good as medicinal brandy. And once in a while, somebody would come back that had just been shaken up a little bit … so they sent him back and cases like that, well, he was perfectly alright, he’s just kind of jarred. But he was too good a guy to lose…. See, mostly it was artillery and mortar. It wasn’t small arms fire much. I would say at least eight-five percent of the casualties we had were from mortar fire.

…Well, you’d know that your people were moving out, moving into where that shellfire was landing or trying to get through it. Then you knew they were going to start coming back. But you were always ready for it. They always had things made up and things there ready to do what you could, as fast as you could. But there weren’t many what you’d call big days. There was a few, where it was a steady stream of casualties coming back in. Not like you see on [television] or anything like that. Maybe the hospitals had that, but we didn’t. Because your men were scattered so much … But I don’t ever remember leaving anybody. That was supposed to be the deal, if you were moved, you just left them and somebody else’d pick them up.

“How the hell did you do those kind of things, day after day?”

Decades after the war, Pte Miller ruminated about his life in action:

…I was thinking the other day, how you become immune to something like that. I don’t like blood now. I didn’t like it then, but it didn’t bother me … that was what you had to do and you did it. And you could just, well, you’d go and wipe your hands before you had your dinner, that kind of thing. But as far as working in it, no, I can’t ever remember, even people I knew, like personal friends, that were all banged up, it still didn’t bother me. And yet today I’m not sure whether I could do it again. I don’t think so, whether I’ve become old and sensitive to other people’s feelings. I doubt it. But it must have [been] something I was watching on television, and that crossed my mind. How the hell did you do those kind of things, day after day[?] It wasn’t just an isolated case, cause we sure as hell weren’t trained doctors or anything like that.

“It’s done, you did the best you could for him, and you hope he makes it”

He concluded:

…We don’t talk about it, we don’t talk about the people. It just had to be, there’s no point in dwelling on it. It’s done, you did the best you could for him, and you hope he makes it.

The garrison duties of pipers and drummers were far-off memories by the first week of August 1944. The company pipers did, however, play the Argylls’ lament, ‘Flowers of the Forest,’ at the temporary gravesite of the 37 Argylls killed in action.

“We lost our piper, [Pte Richard] McDonald”

Pipe Dick McDonald was killed at Hill 195 (see Capt John Lloyd Johnston). Pte J.J. Murie (himself a doctor after the war) remembered it. He was with 18 Platoon, D Coy:

I don’t think we were told specifically that we were above the [Germans]. It wasn’t long after dawn broke that we started to get mortared and shelled; and then it became pretty obvious that there were Jerries pretty well all around us … our company was almost on the forward slope of 195, and so there was shelling coming from forward of us and on both flanks…

We had a fair number of casualties at 195 … We lost our piper, [Pte Richard] McDonald, and a fellow by the name of [Pte Donald] MacMaster were [sic] killed. A fellow by the name of [Pte George M.] Martin was killed. They were killed in the slit trench next to me and an 88 had landed in the slit trench and killed both of them.

“He was my very best, like, you know”

Pte Andy Scott, a B Company piper and stretcher bearer, remembered McDonald well:

I felt very bad when Dick McDonald was killed. He was my very best, like, you know. And I only saw him the night before and I said, “Keep your head down” … In fact, he was in a slit trench, and the mortar came right down … and just covered him in …

“a fine promising young piper”

Piper Murdo Miller never forgot “Dickie McDonald, my friend, he was a coy piper, so he got killed.” Pte Richard R. “Dick” Gillespie was another piper who never forgot:

We had [one] other in the band wounded [Pte Charlie Richards] and one killed – [Pte] Dick McDonald, a fine promising young piper. A shell came right into the slit trench with Dick on Hill 195.

…The band all got pulled out … So the order came down then that all bandsman were to be pulled out of the line and given jobs behind the line. Because, well, we had Dickie McDonald was killed [10 August 1944], Charlie Richards was wounded [2 August 1944], and who else? That’s the only two. But when you’ve only got 12 pipers and you lose two of them, it’s [a] pretty high percentage.

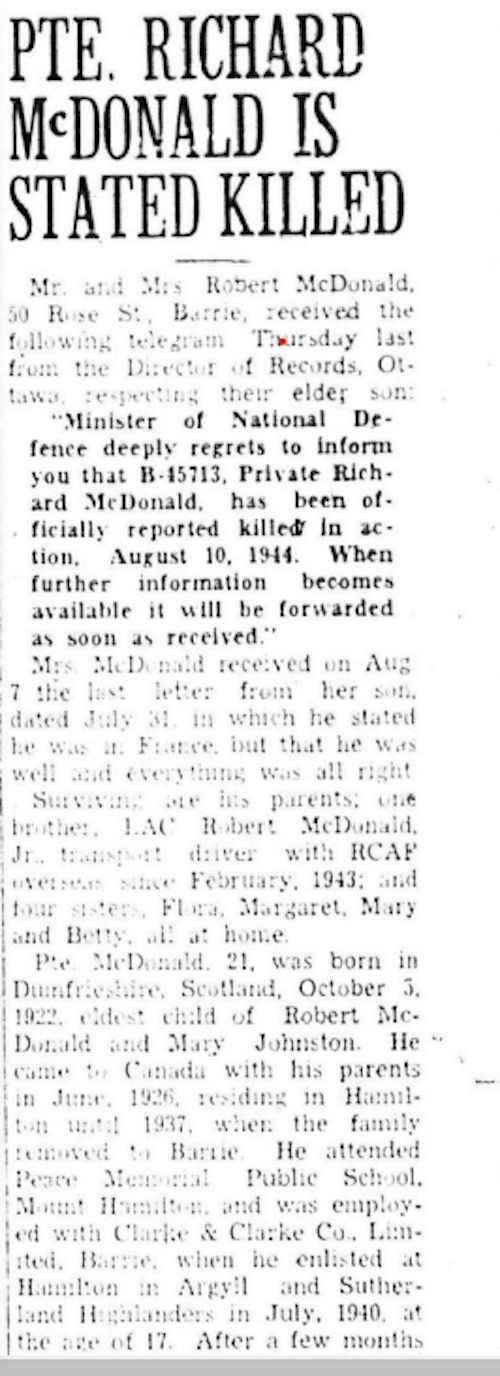

Pte McDonald’s obituary appeared in the Barrie Examiner on 31 August 1944.

Cenotaph in Barrie, Ontario.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

The Argyll Regimental Association and CWO Norm Wills, CD, placed a poppy in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in honour of drummer Earl Layton Wardell, who served the Regiment in war and in peace all of his long life. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy for the Field of Remembrance.

Piper Dickie McDonald in Jamaica.

Barrie tannery.

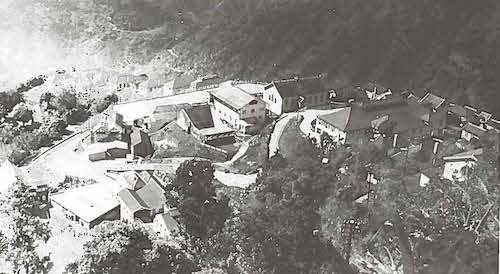

View of the barracks in Newcastle, Jamaica.

Playing “Retreat,” Newcastle, Jamaica.

Pipe Major Frank Noble.

Laying up The Colours, 10 November 1940.

The Pipes and Drums in front of Buckingham Palace, 27 March 1943.

Obituary (part 1), Barrie Examiner.

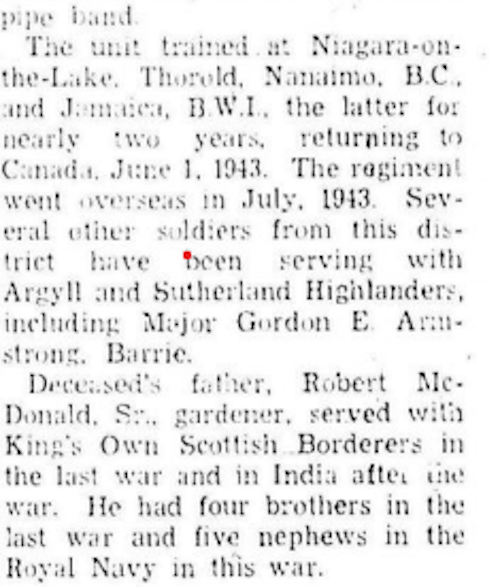

Obituary (part 2), Barrie Examiner.

Obituary in the Hamilton Spectator.