Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

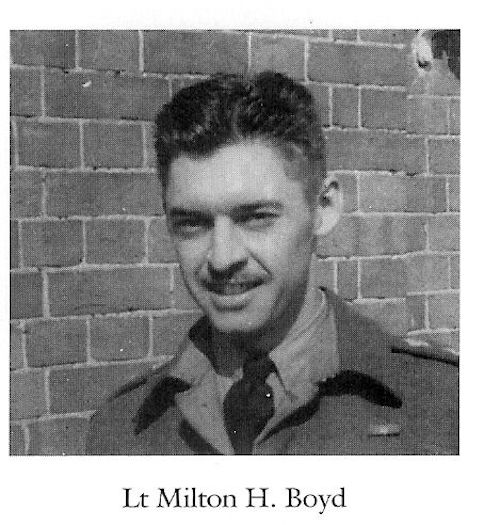

The Black yesterdays project started in the summer of 1984. I have been familiar with Lt Boyd’s life and death since then. LCol Don Seldon, the adjutant in August 1944, spoke about him, as did Maj Robert Lillie and many others. For many months in 1943 and 1944, Milt Boyd wrote the daily entries in the unit war diary. They are, by turns, perceptive, observant, whimsical, telling, and piquant. The 1st Battalion was lucky in its war diarists, all of whom shared many of these qualities and more.

I offer my thanks to Jeff MacIntyre, the son of Milt Boyd’s widow and her second husband. He has been most helpful with pertinent reminiscences and the sharing of family trees and images.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

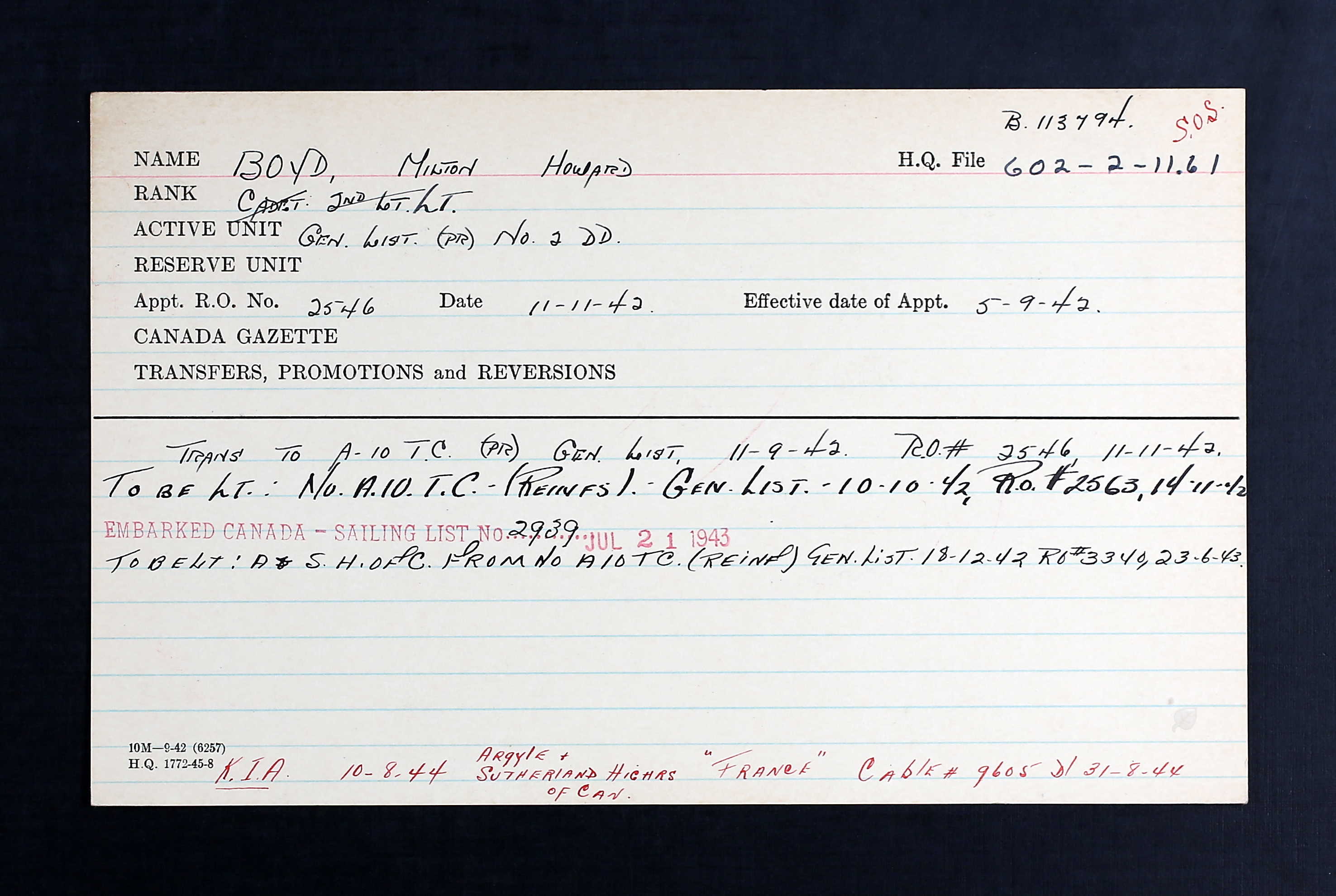

Lt Milton Howard Boyd (1917–44)

KIA 10 August 1944

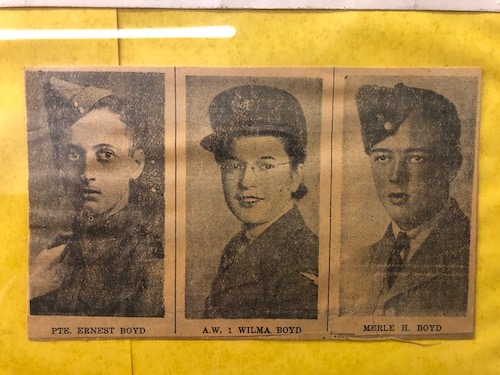

Milton Howard Boyd was born on 16 November 1917 in Lavant Station, Ontario, a small hamlet in Lanark County, about 50 minutes’ drive northwest of Perth. William John Boyd (1889–1951) and Ethel Beatrice Praskey (1892–1982) married in Lanark in 1911. They had five sons and three daughters; Milt was the oldest. His father was the CPR’s station agent at Lavant Station.

“Above reproach … Useful all round man”

Milt Boyd received his early education at the Perth Collegiate Institute, where he achieved “Sr.Matric” [senior matriculation]. While there, in 1936–37, he was a “lance-corporal in cadet training.” He then went to the University of Toronto and its Faculty of Pharmacy, his chosen profession for the post-war period. He served in the militia from 8 June 1941 and received “117 hrs training Camp Niagara”; he was promoted corporal on 5 February 1942. Boyd enlisted in Toronto on 5 June 1942. Cadet Boyd was 5’, 9”, 134 lbs., with a “dark” complexion, hazel eyes, and black hair. He had no health problems and his medical category was A1. A university student, he was an obvious candidate for officer training. His “Confidential Report” at No 30 Officers Training Centre, Brockville, from 12 June to 5 September 1942 notes that he had been a cadet in school and that his hobbies were “Taxidermy and photography.” Attaining a grade of “C,” he was promoted “2-Lieut.” and deemed “fit to continue training as an officer in INFANTRY (R).” Boyd’s character was exemplary in all regards: “Keen”; his common sense – “Sound judgement”; his sense of responsibility – “Dependable”; his military knowledge and its application – “Good in theory”; his qualities of leadership – “Confident”; his personality – “Balanced”; his instructional ability – “Good, methodical”; his appearance and bearing – “Intelligent”; his conduct – “Above reproach”; and the general comment – “Useful all round man.”

No.1 Company, A10, Camp Borden, Ont. Milton Boyd is in the front row, third from the right.

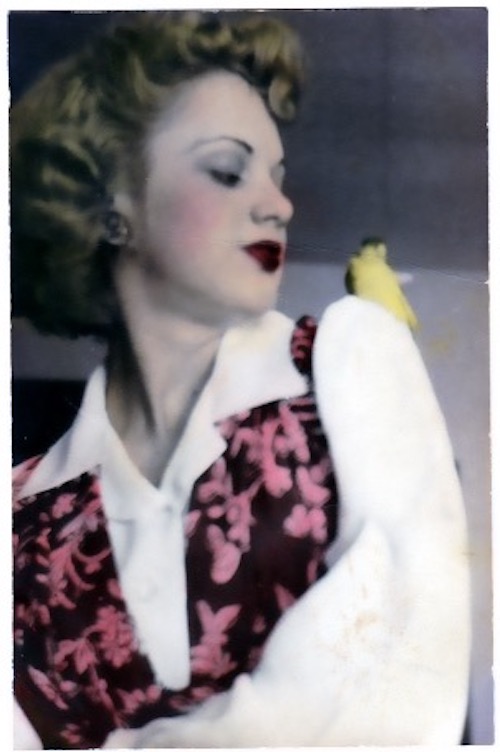

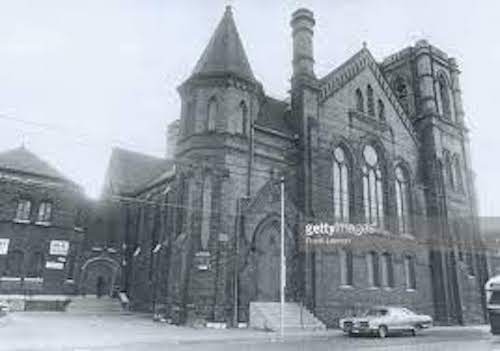

“dazzled by Milton’s Highland uniform”

Struck off strength at Brockville on 11 September 1942, 2Lt Boyd was posted to infantry training for officers at Camp Borden and taken on strength there the following day. On 10 October, he was promoted Lt; three days later he received “permission” to marry. Geraldine Estelle Quarrington (1921–90) and Milt Boyd married at Bathurst United Church in Toronto on 7 November 1942. In recent years, Jeff McIntyre (Geraldine’s son by her second husband) heard from a cousin who “was a pretty young boy at the time and he was at their wedding and remembers being dazzled by Milton’s Highland uniform. He mentioned how fine the tartan in his kilt looked.” Unfortunately, Lt Boyd did not wear Highland kit of any sort on that day. Ten days later, the Argylls took him on strength “as reinforcement.” He joined the Argylls in Jamaica on 20 December 1942 at Up Park Camp in Kingston along with 15 other ranks; the group arrived “by P.A.A. [Pan American Airways]. Boyd’s sojourn in the sun was brief. It was routine during the 22-month stay for officers and NCOs to return to Canada for specialized training. On 27 February 1943, he proceeded to “CSTC [Canadian Signals Training Centre} Kingston,” along with Sgt Everett Lampman. There he qualified as an “Infantry Signaller” on 19 April 1943. He went to No.2 District in Toronto on 11 May 1943, presumably to await the Argylls’ return from Jamaica; the unit sailed from Kingston on 20 May. Granted leave from the 11th to the 24th, he was “Recalled” on the 20th and attached to the 1st Battalion Scots Fusiliers until the 25th. The unit landed in New Orleans on 23 May and boarded CPR trains immediately, arriving in Detroit at 1045 hours on the 25th. The battalion marched into Niagara Camp on the 26th. Boyd rejoined the unit that day with Capt John Farmer, Lt Don Seldon, and a number of NCOs and other ranks. Lt-Col Ian Sinclair granted 147 other ranks “48 hour leave” if they lived within a 100-mile radius. Boyd’s wife was in Toronto and he received a furlough from 27 to 30 June 1943.

Events moved rapidly as the battalion moved from Camp Niagara, to Sussex, New Brunswick, to Halifax and overseas. The unit landed in Scotland on 28 July and was moved quickly to its quarters in New Hunstanton. On 1 August 1943, Lt Boyd assumed the duty of keeping the battalion’s war diary. He was in a long succession of witty, perceptive, and entertaining diarists: Lt Don Seldon, Lt Paul Winchester, Capt R.D. “Pete” MacKenzie, and Capt Malcolm “Mac” Smith. Lt Claude Bissell, whose pen was attached to a PhD, was yet to come.

“rather poorly attended due to inclement weather and general lassitude”

Often the daily entries, especially whilst in the United Kingdom, were matter of fact. For example, his first entry on 1 August was a model of brevity: “A battalion church parade was held in St Paul’s Anglican Church [Camberley] which is within the Unit billet area.” Boyd was warming up. Subsequent entries observed the beginning of company route marches, the weather (time and time again), the establishment of passes, visits by dignitaries, a pay parade, the return of Argylls such as LSgt Bill Shields who had been detached on special duty, medical exams for “V.D. and skin disease,” entertainments, dances, the arrival of more of the unit’s equipment with an editorial comment (“allowing those affected to resume a more orderly existence”), and the establishment of a new training syllabus (9 August). The later development was worthy of detailed elaboration as befitted something at the heart of the battalion’s fundamental purpose, training for battle. He commented on problems during exercises. At the end of September the unit spent a few days in the field with the British Columbia Regiment (armoured). “Many things,” he opined, “have been learned on this scheme.” What stood out most for him was “supplying the food to the troops seemed to be the most urgent and difficult task.” It took days before “some semblance of a system was obtained and maintained.” The logistics of supply were critical to the functioning of a battalion in battle. Water, ammunition, gas, and food were essential and they had to be there “at the right time and place.” On 17 October 1943, a “voluntary church parade” was “rather poorly attended due to inclement weather and general lassitude.” After a wretched end-of-October exercise, “a miserable week,” noted Capt Pete MacKenzie, OC for D Company, Boyd wrote: “Pay day! One silver lining as regards field exercises is the inability to spend money.”

“A fine soldier and comrade has been lost but a tradition found”

Boyd rose to the occasion on 29 October, noting the grenade range exercise that resulted in the death of ASgt John “Jock” Rennie. The “shadow of tragedy fell across the Argylls. A tragedy no less sombre because of the added touch of heroism…. A fine soldier and comrade has been lost but a tradition found. A tradition of coolness and courage in time of stress. The men of this regiment will never forget.” The next day brought this comment on a trip to Cambridge University, arranged “under the auspices of the Padre … for men who had been out of touch with civilization for upwards of a month…. The hob-nailed shoes of soldiers seemed a little out of place in the cloistered halls ….” Only “a little,” it should be noted. Reveille came on 1 November “at the dusky hour of 0500” along with a “hasty breakfast.” Boyd could be acerbic. Of EX Bridoon: “Unlike some of our earlier schemes, this one had a definite plot and continuity ascribed to it …”

“a quality that perhaps best expresses the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment”

Boyd had his lyrical moments, such as this reflection at the end of Bridoon:

…With the “war” over, the camp [twenty-five miles south of Frog Hill] assumed something of the festive air of a summer resort…. Spurts of flame from bonfires knifed holes in the surrounding darkness. Singers, accompanied by mouth organs and even one guitar, blended with one another from different sections of the grove.

Argyll sing-songs have a peculiar character of their own it would seem. Starting quite spontaneously at any time or place, the selections range from Scottish ballads to Jamaican folk songs always liberally sprinkled with the popular ditties of the day. When aided and abetted by the soft glow of a camp fire they have a quality that perhaps best expresses the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment.

Of C Company’s dance on 12 November – “long postponed due to operations in the field” – it “proved to be worth waiting for”: “Femininity was present in quality and quantity, beer inexpensive and reasonably plentiful.” The spiritual and the physical state of the unit elicited this pronouncement. On Sunday 21 November, with the weather “depressingly miserable,” the “voluntary church parade was rather poorly attended.” On the other hand, a “hockey game in the afternoon had a much better attendance, with the men thoroughly thrilled by their first glimpse of this virile pastime in two years … “

“every race, creed and condition have been poured into the melting pot from which is brewed soldiers and Argylls”

Occasionally, Boyd’s entries assumed an analytical bent. He had been with the unit since its days in Jamaica, witnessed the loss of 7 officers and 120 men on 14 June 1943 because of age and medical condition, and the arrival on 5 July of 152 other ranks from Camp Shilo, Manitoba. During the first months in the United Kingdom, there were more changes. The door to the battalion was a revolving one and Boyd reflected tellingly on that fact in terms of the unit’s composition:

With time and the natural course of events, the personnel [and] the character of the Regiment is changing. Day by day old familiar faces disappear to be replaced by new. While transfers account for some of these, in the main it is ailments of one kind and another that cause a steady drain on Regimental strength. When released from hospital the erstwhile Argyll goes to C.I.R.U. at Aldershot and from there to any Infantry unit that may need replacements, only the fortunate few find themselves again with their old unit.

Lucky, indeed, is the rifle company that can boast of having over thirty “old originals” on their roll, so that a Battalion once tinged with the Hamilton, Toronto atmosphere, has become definitely “naturalized” in flavour. Stalwarts from all parts of the Dominion, with still a few from “south of the border”, of every race, creed and condition have been poured into the melting pot from which is brewed soldiers and Argylls.

“somewhat Buck Rogerish in appearance”

Boyd provides a good sense of the battalion’s celebration of Christmas and the New Year. There was food in abundance, parties for local children, a dinner for the troops served (as was the custom) by the officers, beer, parcels, and cigarettes (100 per man). Of the new anti-tank gun, the PIAT, it was “somewhat Buck Rogerish in appearance.” The arrival of “these vicious little weapons [means] the mechanical monsters [tanks] are not so great a threat as of yore.”

“brens, stens and rifles”

While away on course, Maj Art Hay took over Boyd’s duties as the regimental scribe. He returned to them on 1 February 1944. There was often a tone of bemusement. On the day of an inspection at Uckfield on 4 February, he commented: “up betimes, as Pepsy [a reference to Samuel Pepys, the renowned 17th-century diarist] would say … Reveille was at 0545 hours with breakfast in the frosty darkness at 0630 hours.” The conclusion of OP STAMMER on 6 February spurred him to an almost exultant reaction:

The sight of the unit advancing in line … was impressive and when the final assault … came, even though the section and group leaders controlled the fire of those under them, with artillery, 2 and 3” mortars, brens, stens and rifles all firing at the same time all Hell seemed to have been let loose and one was instilled with a great and glorious feeling. As we underwent this true aspect of the real thing, this inner feeling seemed to convince us that we were capable of nothing but victory. When the fire power of a unit and support is devastating, the Allied barrages must be magnificent!

“if or when Lady Luck ceases to smile”

The amphibious training in Inverary, Scotland, in mid-February ended on the 22nd: the “scheme is over but the memory lingers on. While no one will be sorry to leave …” On the 27th, back at Uckfield, there was “another compulsory church parade.” “Freedom of religion took,” Boyd thought, “another punch in the eye.” There was more training, the formation of the Scout Platoon, a review by King George VI with the “regimental glamour” of the Pipes and Drums (see Pte Richard McDonald) on display, and the establishment of the reinforcement company of 6 officers and 125 other ranks [E Company] on 14 March. Boyd observed:

Morbidly inclined individuals in the present establishment can amuse themselves trying to pick out the particular replacement that will be filling their shoes if or when Lady Luck ceases to smile.

“Never before has the morale been so high”

Rifle companies did more than just train in the hills, they were in Boyd’s mind, “cavorting” on them, a concept almost thoroughly lost upon those thus engaged. The unit’s entertainment on the evening of 27 March “had all the elements … a hot swing band, pulchritudinous girls and first rate gags …” Training quickened and there was more work on ranges. When Prime Minister King inspected the unit on 17 May at Buxted Park, he was, as Capt Bob Paterson put it, “booed.” Cpl Tommy Dewell expressed it a little less delicately – “we booed the piss outta him.” Lt Boyd took no note of it in the war diary. Lt-Col Dave Stewart “knew Mackenzie King very well. I didn’t like him … he was a sissy, an old fuddy-duddy. And he deserved to be booed.” “This is D Day for the invasion of France,” Boyd wrote on 6 June, the “day is bright and sunny.” Entries turned to embarkation plans, officers wearing loaded side arms, and the waterproofing of vehicles. “Never before,” Boyd scribbled on 13 June, has the morale been so high and never before has there been greater cause for it to be so high.” The unit was “anticipating it’s [sic] immediate future, everyone is confident of victory over any obstacle which may be in its path.” 18 June was “a fine war day.” There were more route marches, and Lt-Col Stewart advised the troops that there would be further delays. Boyd’s last initialled (M.H.B.) entry was on 30 June 1944. After that, they are initialled by C.T.B. (Lt Claude Thomas Bissell became IO on 27 August). On that date, many battalion documents were captured or destroyed at Igoville, France. It seems likely that Bissell merely initialled copies presumably made by Boyd. The war diary assumes its Bisselian only after he took over.

“Short Intelligence Crse”

During the period in the United Kingdom, there was time for more courses, lectures, and tours. On 16 November, he went to Canadian Army headquarters for the “Short Intelligence Crse,” which was true to its name; he was back at the unit three days later. He took the “War Intell” course in Matlock, Derbyshire, returning on 23 February. There was also time to take in some of England’s sights with other officers. Lt Alf Henderson, C Company, wrote to his father on 27 March 1944:

Yesterday Milt Boyd, Tommy Wright, Gord Sloane and I went to Tunbridge Wells more or less to see the town and have dinner there. It is quite a lovely town although it doesn’t seem to [be] quite as old as I had anticipated. There is quite an impressive public library and art gallery there …

On 16 May, he “attended a tour” with Maj Don “Pappy” Coons, B Company commander, and other officers of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division at Gatwick Airport “being shown the methods of producing aerial photo’s [sic] and maps.” On 14 July, the unit received information as to the composition “of the adv party for overseas duty.” Maj Bill Cromb would command. Lt Boyd, Sgt Mike Flynn of the Pioneers, Sgt Vic Mann of A Company (KIA 29 October 1944), and Cpl Russell Morden of the I section joined him. They left for their departure area on Sunday 16 July 1944, for France on the 17th, and disembarked in France on the 17th.

“together with the IO became more or less general staff officers to the CO”

The routines of the adjutant and IO were transformed in battle, more so perhaps for the former. Capt Don Seldon was the adjutant. His job changed according to Lt-Col Dave Stewart’s needs and his appreciation of battle; moreover, his anticipation of that fact brought changes before arrival on the battlefield:

Before we went into action, Paymaster [Capt Frank W. Woods] took over most of the paperwork from the Adjutant, and so that I … together with the IO became more or less general staff officers to the CO. And I hadn’t done so much of that during training, so … I think perhaps I could have been a little better prepared for exactly what the Adjutant was supposed to do in action.

The Argylls arrived in the Normandy bridgehead in different parties departing on different days. The battalion had all elements together again on the 26 July at Tierce. Within two days, the unit moved through the devastation of Caen and its memorable scenes of destruction, scenes etched forever into the collective and individual responses to the first images of battle. The deaths of Pte Percy Hindle and Pte William Daniel McCann made war a “reality” and provided a potent taste of the Normandy battlefield’s deadliest weapon – artillery. Argylls withstood and endured the persistent shelling at Bourguébus that resulted in the death of Pte James Bannatyne and others on 2 August. Its first offensive action at Tilly-la-Campagne on the 5th failed and brought more casualties, including Pte Joe Carlton, ACpl Coningsby Gooderham, and Pte Bill Wingate. There were two realities to those early days of battle: first, the reaction to casualties, one of battle’s ubiquitous, awful truths; secondly, adapting to that reality, putting training into place, and relying upon leadership at all rank levels. Lt-Col Stewart’s tactical headquarters (himself, the adjutant, and the IO) were also learning. At Bourguébus, Capt Seldon pointed out that Stewart had ordered artillery support for an Argyll patrol “pinned down” between Bourguébus and Tilly. The artillery hit “DFs” [defensive fire targets]. “All you’d have to do,” Seldon recalled, “was give a certain code word and all hell broke loose.” They learned afterwards that “we forgot to give them the stop sign, and they kept on. They used about a month’s supply of ammunition before they were told to stop.” In the first few days, Capt Pete MacKenzie, OC Support Company, said that “the fire was so accurate that people spent most of their time” availing themselves of “whatever cover was available.” It was, he thought, “an introduction to fighting that stood them in good stead in the days to come”:

They were used to being shot at by the time they left Tilly. They knew what to expect, and when we started down the road into France, they were already prepared to accept what came and to fight back.

The “shadowy company” of Argyll dead had more recruits in the coming days, such as Pte Josef Poniedzielski and LSgt Tommy Page. The Regimental Aid Post (RAP) was a scene of blood and disciplined urgency (see The Wounded and the Dead). Stretcher-bearers such as Pte Richard McDonald performed bravely on the battlefield and HCapt Charlie Maclean, the Argylls’ redoubtable and beloved Padre was “really scared … And I thought to myself, ‘Well, you did your darndest to get into this business. Now put up with it …” And he did just that. He took care of bodies, buried the dead reverently and lovingly, helped in the RAP, wrote the families of the wounded and the dead, and provided balm to the living.

Lt-Col Stewart’s leadership demonstrated what Maj Hugh Maclean recalled some 40 years after the war – “soldierly virtue, morale” – “the soldier’s absolute determination to do his duty to the best of his ability in any circumstances.” Maclean took his cue from Col John Baynes’s writing on this subject and applied it to the Argylls and the “role of wise, thoughtful, compassionate leadership; and … that ‘intense group loyalty at every level.’” For Maclean, “the intense group loyalty” took flame at Hill 195. Dave Stewart’s and the Argylls’ military reputations took root (or flame) at 195. LCol Brien A. Reid devoted a chapter of his book on OP TOTALIZE to “facts versus myths.” He is critical of generalship and staff work – “a cut below that of the other Allied armies” – while cognizant of “a lack of practical experience and a rather bureaucratic concentration on process, in itself a sign of an organization still groping to finds its way. He questions “the recurring Canadian practice of failing to allot enough troops to tasks, considering the setbacks that resulted.” At the unit level, “where the actual fighting is done, there was little to find fault with, other than perhaps inexperience, and the artillery verged on excellence.” He provides three examples from the 4th Canadian Armoured Division demonstrating “that most intangible of assets, the warrior spirit”: a platoon attack led by an Algonquin Regiment lieutenant, a troop assault by the Canadian Grenadier Guards, and “Dave Stewart’s infiltration … onto Point 195.” He also provided two other examples by the 8th Brigade of the 3rd Division. Historian Terry Copp considers Stewart’s leadership, along with that of Lt-Col “Swatty” Wotherspoon of the South Alberta Regiment “outstanding.” Historian LCol John A. English described the Argylls’ action at 195 as “probably the single most impressive action of ‘Totalize.’”

SS Major-General Kurt Meyer commanded the division opposing the Canadians. In a post-war interview, he derided British and Canadian planning as “absolutely without risk.” To Dave Stewart, battle was “disorganized, complete disorganization…. It was a shambles, really.” The leader’s challenge was to navigate chaos. Stewart said once that a good infantry officer must know two things, people and ground. “I had to improvise … I never went by the book … it is the Tory personality.” “When we received the orders to take ‘Hill 195’ it was late in the afternoon and two other regiments had tried but were misdirected and got off the track. I mentally wrote the Argylls off as well as myself.” The British Columbia Regiment (BCR) lost all but one of its tanks and its CO; the Algonquin infantry battalion suffered heavily, and its CO, Art Hay (formerly an Argyll) was badly wounded in a failed attempt at the high point on the road to Falaise.

“up there just with a jeep and some members of the Scout Platoon, and the IO”

“I was always up front,” Stewart declared, “you can’t win battles being behind. You’ve got to be there. His adjutant, Capt Don Seldon, described the CO’s approach and its impact on the battalion:

[Stewart’s] method of operating was to be mostly up with the forward companies, [with] what he called his Tac Headquarters. And he would go up there just with a jeep and some members of the Scout Platoon, and the IO…

I think he added so much to the morale of the unit by being up in the forward locations. And I think he liked to fight his own battles and not have brigade looking over his shoulder all the time…

By the end of the month, Lt Claude Bissell was IO and part of Stewart’s “Tac Headquarters.” He took similar measure of the CO’s battle procedure and its concomitant effects:

I think again it was the man’s simple power as an individual, his capacity to generate confidence and to downplay the emergency without at the same time turning it into something which it wasn’t. Respecting the seriousness of the operation and yet not turning it into an emergency … I suspect, a good many commanders felt they were part and parcel of the turmoil and confusion. Somehow … he was above it, and always seemed to be…

“Get a job done; save lives”

At Hill 195, Dave Stewart improvised without communicating his plan or his intentions to higher formations. He had little use for the so-called book; he understood command as a moral trust. Famously, he said, “A CO to my mind is the most lonesome occupation that could be…. Get a job done; save lives.” The plan was Stewart’s plan, the style was Stewart’s. Hugh Maclean, in his post-war ruminations about the 1st Battalion wrote:

… the regiment’s style was Stewart’s style … there was a battle to win, or lose, and a certain style to maintain. A manner, if you like, with which to confront the inscrutable face of battle, and endure in spite of it.

Capt Lloyd Johnston commanded the Scout Platoon, which was under the CO’s direct command. He was one of Stewart’s favourites:

I took the scout platoon with me and we reconnoitred the route I had chosen. On the way back I left members of the scout platoon at strategic points, to guide the Battalion, so I could lead them up to the high ground.

Capt Bill Whiteside commanded the Anti-Tank Platoon of Support Company. He remembered:

the CO came back and we had an O Group. And it was at night, and he said, “This is what is happening and the first company moves … in 20 minutes…”

“warrior spirit”

Stewart’s Orders Group performance was a bravura one. He had mentally written off the unit. The slaughter of the BCRs and the Algonquins was not lost on him. COs did not lead battalion-scale infiltrations. Reid’s example of the “warrior spirit” was at a small level. Here was the warrior spirit with four rifle companies, Support Company, and the Scout Platoon:

I took them in single file to the high ground and luckily it was ‘Hill 195’ and we went right through the German lines. When we reached the top, I advised the company Commanders to dig in and I distributed the [Battalion] about the hill. When it came light in the morning, the German reacted very strongly and shelled our positions.

I interviewed Lt-Col Stewart in 1986. I was curious about his decision to lead the battalion twice that night, first with the Scouts and then with all of the rifle companies. My curiosity sharpened with his revelation that he had “written off” the unit. I suggested, in the form of a question, whether his action that night was akin to a captain going down with his ship. There was no immediate answer, but I was reminded of Claude Bissell’s comment about eyes capable of expressing “annihilating disapproval.” He then offered up his pre-war experience in map reading in northern Ontario. He was confident of taking the battalion where it needed to be, and so he did.

The Argylls took the high point without a single casualty. That came later in the day with the counter-attacks. Capt Don Seldon and Lt Milt Boyd were part of Stewart’s Tactical Headquarters that night, a night that displayed brilliant, unorthodox leadership; inspiring leadership; and execution of a bold, audacious plan by a battalion of well-trained soldiers.

“This difficult move had been made with an almost incredible smoothness”

Lt Boyd did not write the unit’s war diary that day; it probably fell to his successor, Lt Mac Smith; it was initialled by Lt Bissell, Smith’s successor. It reads:

The Argylls’ attack on Hill 195 took the following form: A circuitous route to the East and North-East of the feature was chosen, as the area to the West was known to be defended heavily by the enemy. The C.O. sketched the route to the Scout Platoon and they went out in advance to piquet the advance of the Battalion. The advance began at 0001 hours, at 0430 hours the leading elements were within a few hundred yds. of the objective, without as yet having encountered any enemy. There the C.O. pointed out to the Company Commanders their respective positions – positions that previously [had] been picked from the map – and the marching troops were despatched to them forthwith with the instructions to search the area for enemy and “dig like hell.”

Meanwhile the vehicles had reached a bottle neck caused by unmarked hedgerows; the C.O. and Lieut Johnson made a recce of the immediate area on foot and, with the aid of wirecutters, improvised a route that bypassed the obstacle. These two officers then led the vehicles to their areas.

At the same time Capt. Whiteside made a recce of the Battalion area and drew up an anti-tank plan, enabling the troup [sic] of 17 pdrs [anti-tank guns], and the platoon of 6 pdrs [anti-tank guns], to get into position.

Although the unit had reached Hill 195 only about half an hour before first light, nevertheless, when morning came, it was well dug in and prepared for counter-attacks. “C” and “D” were forward, supported by “A” and “B” Coys. B.H.Q. was slightly in the rear, in an orchard. This difficult move had been made with an almost incredible smoothness. The enemy surrounded us on three sides; yet the only enemy who knew of our arrival were some that “B” Company had discovered when they reached their Company area and whom they used to speed the process of digging in. No casualties were suffered by the Battalion during the move and the taking over of the position.

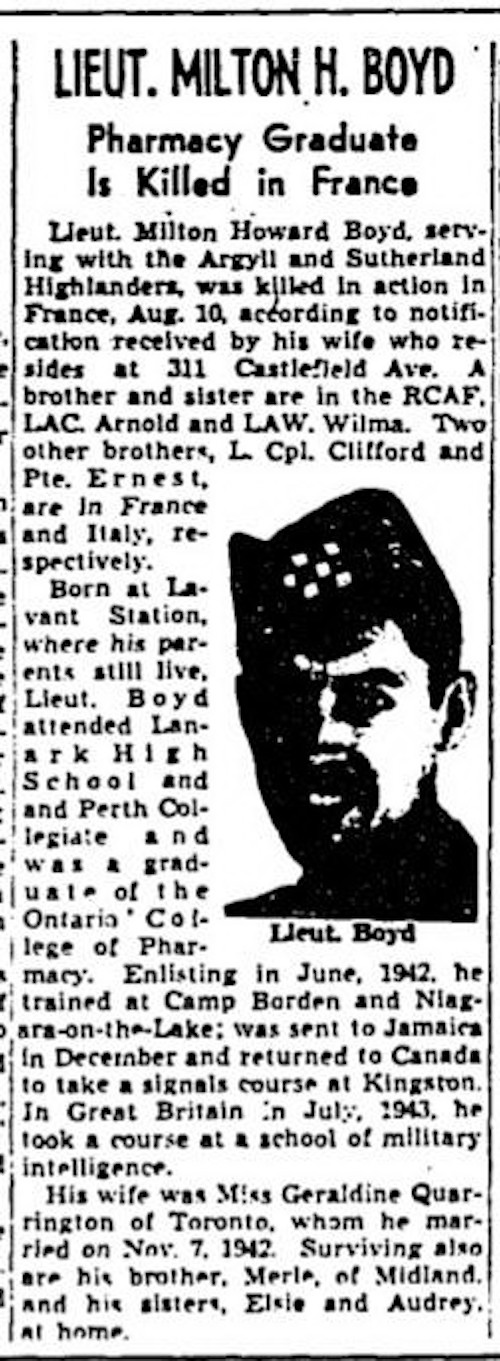

In the morning the enemy awakened to the situation and began to react violently. He opened up on our position with heavy mortar fire and sent out a force to deal with one of our 17 pdrs., which was defended by a platoon from “A” Coy. and the Scout Platoon. In the ensuing skirmish the enemy was beaten back and 27 prisoners were taken. While examining these prisoners, Lieut. M. Boyd, the unit I.O., was killed by an enemy 88mm.

During the day the following officers were wounded: Major Coons, Lieut. Fairbrother and Lieut. Donaldson. In the afternoon our Artillery and Typhoons relieved the situation, the former accounting for a great many enemy personnel, the latter destroying an 88mm. gun located near “A” Company. At 1930 hours the enemy attempted a counter-attack in force, but withdrew under our fire. At 2100 hours we were relieved by the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders.

“if or when Lady Luck ceases to smile”

The Argyll advance on Hill 195 started late on 10 August. There were no casualties until first light on the 11th. Seven Argylls died during the counter-attacks including Lt Boyd and Pte Richard McDonald. There were 24 wounded. Astonishingly, Stewart received no commendation for the action; indeed, higher formations did not mention either it or the fact that he disobeyed orders for a direct attack and an immediate one. In February 1944, Boyd commented on the mighty display of firepower in EX STAMMER. To his mind, it assured victory. Yet, Lt-Col Stewart and the Argylls took Hill 195 without firing a single shot. They used lethal force against the later counter-attacks, but the initial sortie was a product of imagination, unorthodoxy, the veil of darkness, and the collective and individual efforts of well-trained soldiers.

For Milt Boyd, as he had written several months prior on the establishment of the Argylls’ reinforcement company and what it portended, Lady Luck had ceased to smile for him.

“and there was poor young Boyd dead”

Maj Robert G. Lillie of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals was attached to the Argylls:

…we [Lillie and the IO, Lt Milt Boyd] had a small shelter dug out. Nothing elaborate at all, with probably just enough to hold it. And we slept there that evening. And I remember being very, very much annoyed by the French radio which was interfering. The French broadcast radio was interfering with our radio. And I was so mad … at those sons-of-bitches sitting there in Paris, ass-kissing the Germans and sending all this dance music out … while we were taking all this shit.

And early in the morning, we were attacked in a kind of haphazard way by German infantry, and we were well protected by this big hedgerow. And they came across the fields at us, and they were getting very close to us, and then there was a tremendous amount of mortar fire. I thought that it was from their side, but it knocked them all down … I’ve always been under the impression that they really – by mistake, of course – mortared their own troops.

…one of the leaders was a handsome German officer – a captain – with an Africa Corps band on his uniform, and he had a leg blown off. And after this heavy mortar fire, their troops went back and they left some dead, and this officer. And he was moaning pitifully and calling: “Kamerad, kamerad” – as if we were his goddamn comrades. But it was very nerve-wracking, and I could tell that it was kind of getting to the men. You didn’t know what to do. And I certainly wasn’t going to go out and get him myself, or send anybody else out to get him. But I went down to the Regimental Aid Post, which was just one hundred yards away … and spoke to the doctor — Dr. Bie — and asked him if there was some kind of morphine or painkillers for something like that that we might be able to throw out to this poor bugger. And he said no, just to let him be and pick him up … when the situation quieted, if he was still there. So I came back — this had taken about fifteen minutes – and there was poor young Boyd dead [and] my pack was there with three or four great big mortar chunks in it … poor Boyd, he was a nice chap too … Absolutely dead, nothing could be done for him at all. And the whole attack just petered out. But this time I was seeing … that Boyd’s body was taken care of and I never did know what happened to that German captain. Couldn’t bloody care less.

“Our Intelligence Officer was killed the day I left”

Lt-Col Stewart wrote to Lt-Col Herb Fearman, DSO, the CO of the 2nd Battalion of the Argylls in Hamilton at the end of the month. Stewart noted that he had been “very busy, so busy in fact that I have not yet been able to write the next of kin of all my killed wounded but I am doing so as rapidly as possible.”Four company commanders had been wounded, one promoted, his adjutant (Capt Seldon) captured, and his IO (killed). “I am fairly well occupied breaking in new people.” Lt Malcolm “Mac” Smith replaced Boyd as IO and a few weeks later took over as adjutant when Seldon was captured. At that point, Lt Claude Bissell of A Company became IO – Stewart’s battalion tactical headquarters. Lt Norm Donaldson of A Company was wounded on the 10th and wrote his wife, Helen Donaldson, ten days later – “Our Intelligence Officer was killed the day I left.”

In short, within one month of action, Lt-Col Stewart lost his tactical headquarters. There was, as Maclean put it, “a battle to win, or lose, and a certain style to maintain. A manner, if you like, with which to confront the inscrutable face of able, and endure in spite of it.” Both Stewart and the Argylls did just that.

“My predecessor as I.O. was killed … So what the hell”

Mac Smith was wounded in 28 January 1945 at Kapelsche Veer (see Pte Donald MacKeracher). (Smith was KIA on 8 April 1945). He wrote his wife on 13 February 1945 from the 9 Canadian General Hospital. His tone was fatalistic:

I don’t know what job I’ll have when I go back to the Unit, and I dont [sic] care. It doesn’t [sic] make much difference, as you’ll realize from reading the Memorial Service program. None of them are sure things, and none too bad. My predecessor as I.O. was killed, and an adj. was taken prisoner. So what the hell …

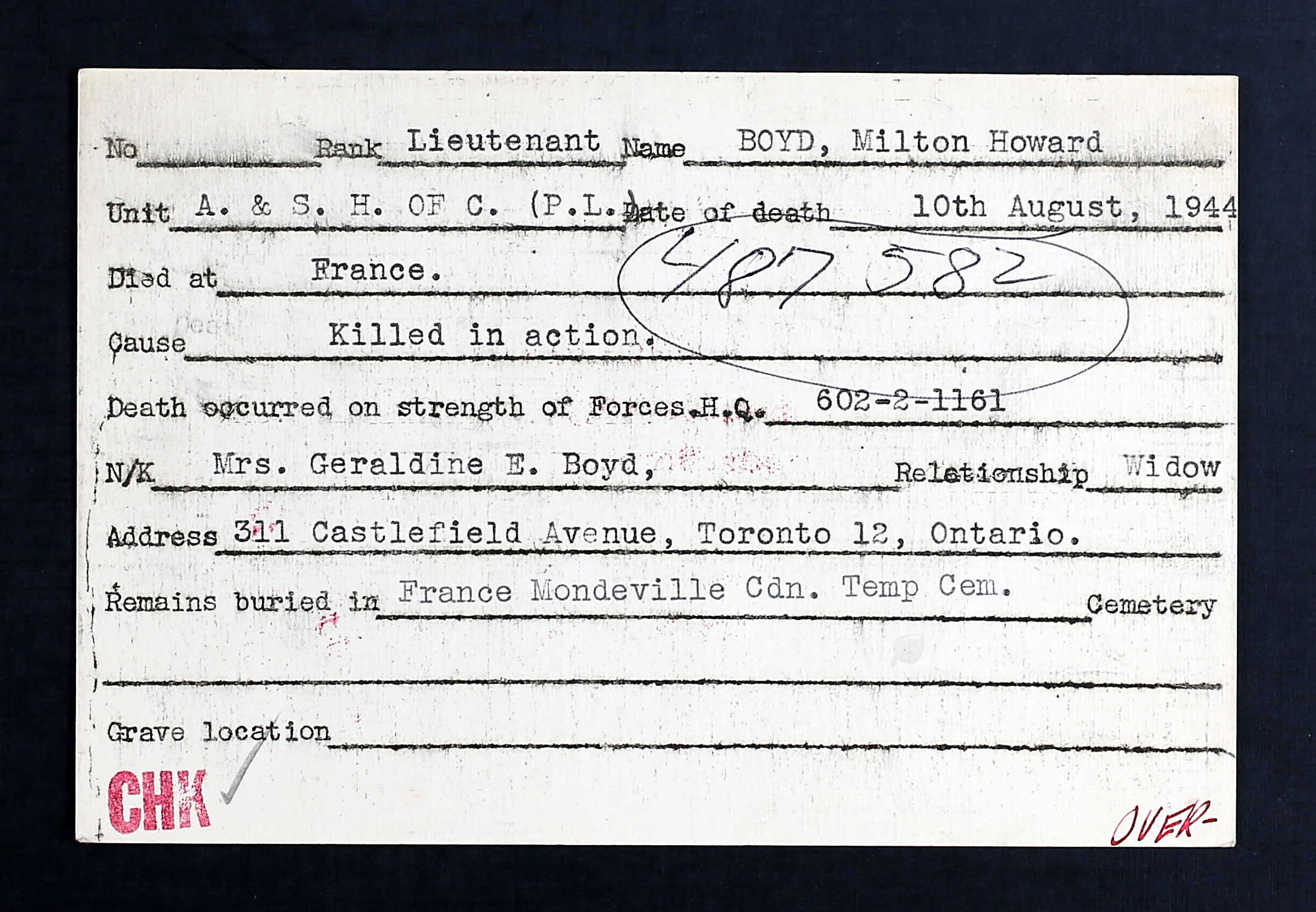

Lt Boyd was buried by HCapt Maclean in a temporary grave at the Mondeville Canadian Temporary Cemetery. Boyd’s personnel file provides few documents relating to his family. His wife, living at their home since their marriage, 311 Castlefield Avenue in Toronto, was notified. Obituaries provide more about the considerable extent of the Boyd family’s service than anything else – it was considerable.

“no idea why his memory had been suppressed in our family”

Geraldine Boyd remarried on 27 October 1945 Lt Clark Martin MacIntyre (1912–89); he was a veteran of the 17th Field Regiment and they married, according to their son Jeff, “very soon after Dad returned from the war I think.” Jeff:

… only learned of his [Milt Boyd’s] existence a couple of years ago. I’ve no idea why his memory had been suppressed in our family, possibly to diminish any sensitivities my father may have harboured about a ‘previous/first love’, possibly because it was just too painful a topic for my mom.

The silence about a previous marriage was not unusual for war widows (see Capt Lloyd Johnston and ACpl Coningsby Gooderham).

“My mom said she’d already lost a husband”

Recently, Jeff wrote:

Last evening I spoke to my sister by phone and she was about 11 or 12 when she overheard my parents in a discussion/dispute about whether I would ever be permitted to enlist in the military in the time of war (Vietnam war was in play at that time). My mom said she’d already lost a husband and that twigged my sister to the shocking news that mom had been previously married. Apparently my sister wigged-out a bit and insisted that she never hear anything else about mom’s first husband. It could be that that was a major part of the reason I was never told anything about Lt. Boyd and he was never openly acknowledged or discussed.

“My mom kept it all her life”

Milt Boyd’s brother Ernest (b 1919) named a son Milton, possibly after Lt Boyd. His name appears on the Wall of Valour of the Perth and District Collegiate Institute. Several months ago, Jeff MacIntyre’s sister gave him a Glengarry with the cap badge of the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish. It belonged to Milt Boyd from his high school days. “My mom kept it all her life.

Wall of Valour, Perth District Collegiate Institute.

The government allowed the closest next of kin to choose an inscription for the gravestone. Lt Boyd’s reads:

WILLINGLY HE GAVE HIS ALL

THAT PEACE BE RESTORED

FOR THOSE HE LOVED.

Grave marker for Lt Boyd.

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Lt Boyd’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Milton and his brother Ernie.

Geraldine Estelle Quarrington.

Milt and Geraldine.

Lt Boyd and Geraldine.

Bathurst Street United Church, Toronto, where Milt and Geraldine were married.

PIAT anti-tank weapon.

Portrait of Lt-Col Dave Stewart by Lorne Toews.

Lt-Col Dave Stewart.

Cap badge of the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish from Lt Boyd’s high school days. Geraldine kept it all her life.

Mundell Donaldson Cemetery Frontenac County.