Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

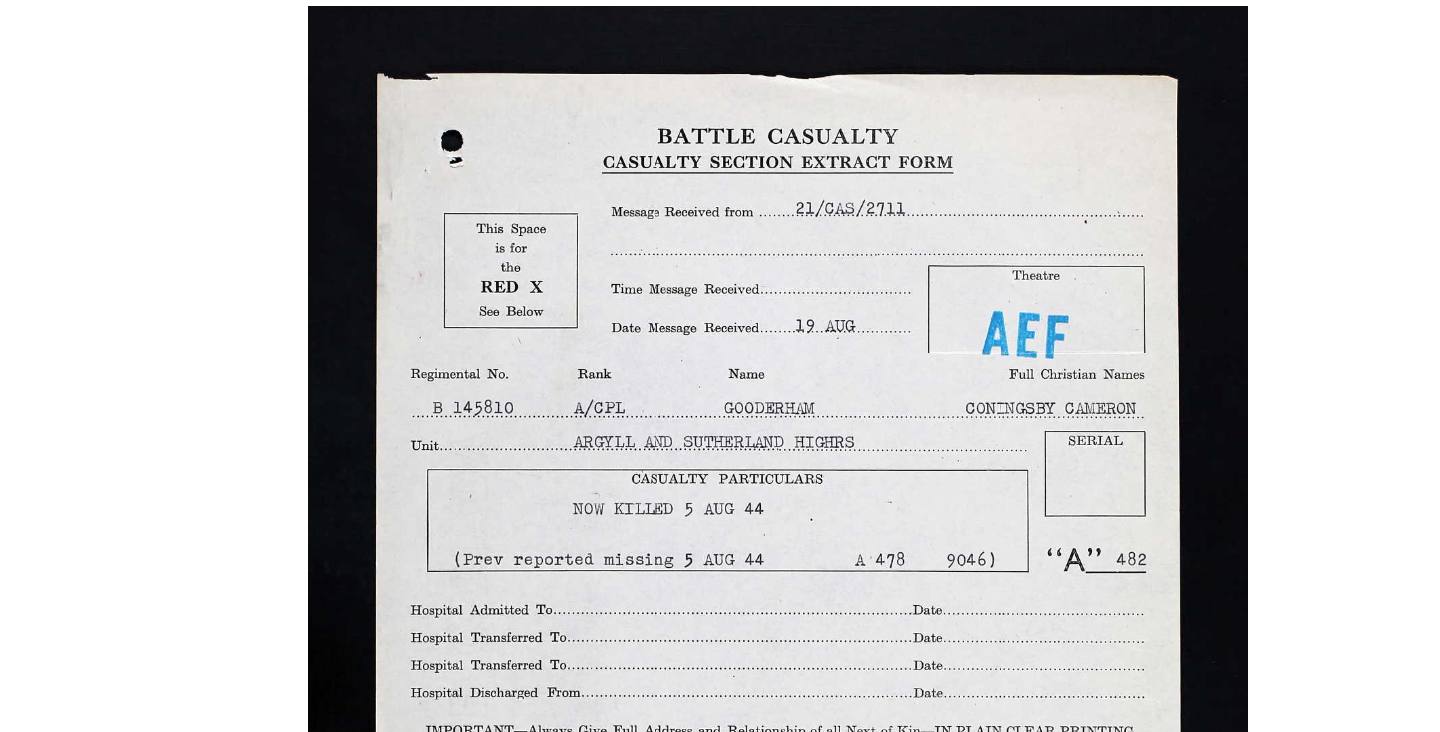

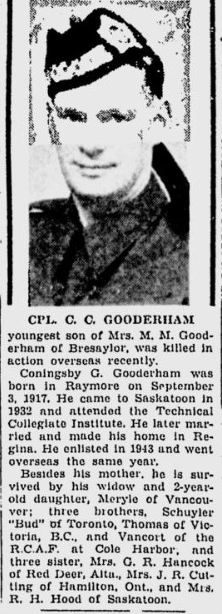

Last year, I became fascinated by the Argyll battle at Veen fought on 7 March 1945, and its futility and its failure. We knew so little about it because it was, in the end, an Argyll affair as a two-company night attack. Many of those who took part were killed, wounded, or became POWs. Most were very recent reinforcements. I covered some aspects of it in the biographies of Pte Wilfrid Ernest Madaire, Pte Edward Robertson Smith, and Pte Clarence Richard Vaise. The Argylls’ great wartime leader, Lt-Col John David Stewart described battle thus: “Battle is disorganized, complete disorganization…. It was a shambles, really.” Young Maj Hugh Maclean wrote the history of the 1st Battalion in the months after the war. He characterized Veen as a failure along with one other battle – Tilly-la-Campagne on 5 August 1944. More than 40 years after the war, Maclean touched on the Argylls’ “style” in confronting “the inscrutable face of battle.” It is difficult, given its nature as Stewart described it, to write about “disorganization” and shambolic confusion. At the level of sub-units within a battalion, platoons and sections, it is even harder. The unit war diary rarely comprehends what happened to all of the companies on a given day, let alone platoons and sections. In some instances, we have interviews from the 1980s and 1990s, plus a few diaries, letters, and specific reminiscences that help – somewhat. ACpl Gooderham met his death in a small unit encounter in Tilly with his section of a B Company platoon. Pte Bill Wingate, also in the same platoon, met his death at a different time and in a separate place – seemingly at least. The face of battle is, as Maclean would have it, “inscrutable,” and the contorted face of death everywhere.

The first few days of battle were harrowing for the Argylls as war became a grim reality. In many cases, the war had already become such a reality for those families left behind. Such is the case of Gwendolyn Gooderham. With Coningsby’s departure, her life altered and, with his death, was never the same. Sacrifice was not limited to the battlefield.

I am grateful to Myrle Margaret Mackenzie (Gooderham), Coningsby’s and Gwendolyn’s daughter, for her candour about her life and her mother’s. A good part of the tale of her family’s life lay in a long-lost trunk once in an attic in a Wisconsin farm. I am appreciative of the research done by Lydia Young Noll’s (Myrle’s sister-in-law) into Gooderham family history and her willingness to share images and research. Lydia put me in contact with Myrle.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

ACpl Coningsby Cameron Gooderham (1917-44) (B 145810)

KIA 5 August 1944

“Good”

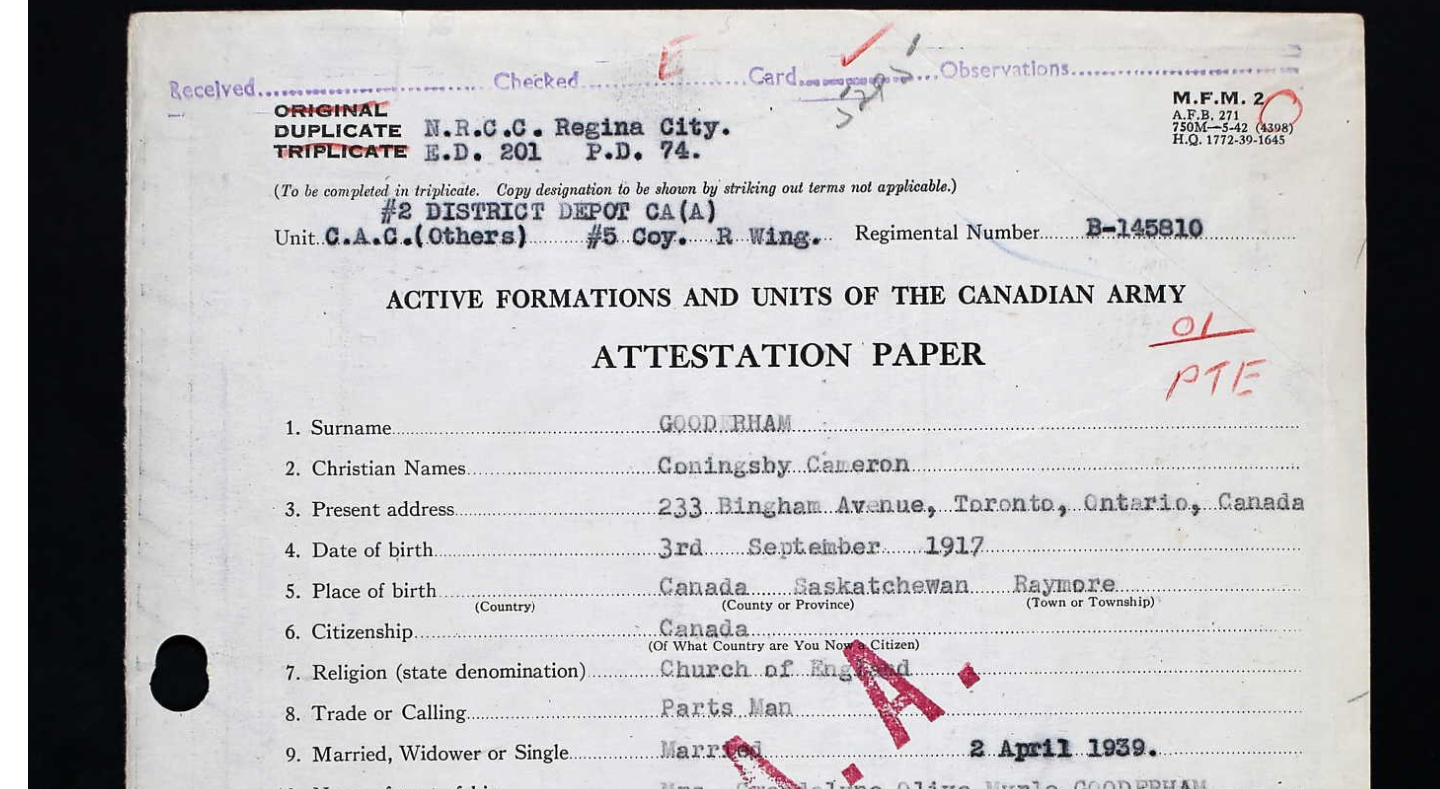

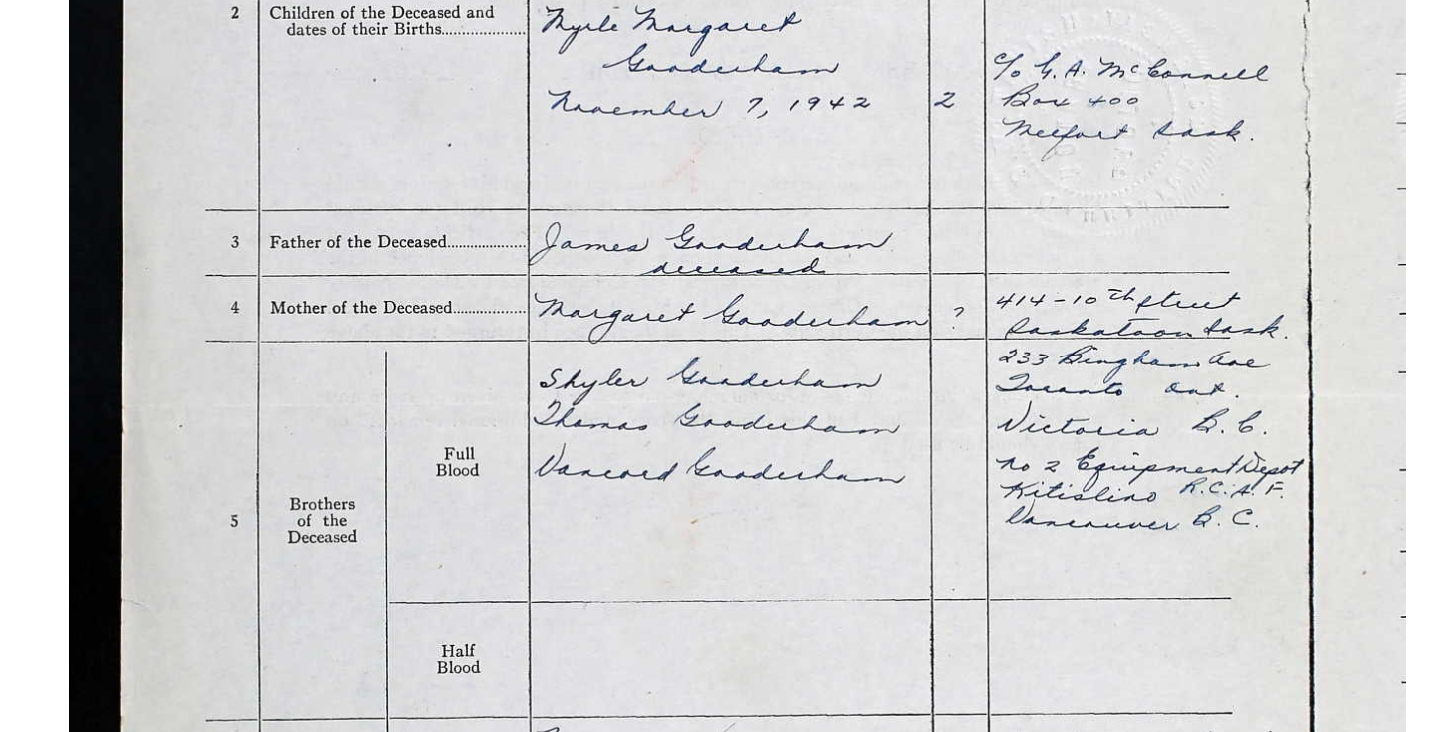

Coningsby Cameron Gooderham was born on a farm in Raymore, Saskatchewan, on 3 September 1917, the youngest of eight children (he had four brothers and three sisters) of James Horace Gooderham (1879-1935) and Margaret McTaggart Currie. He had “wide” experience in mixed farming and was “brought up on [a] farm” in Raymore. Years later, an army examiner rated the “status of home in childhood” as “good.”

“Mechanics + diesel Engineering”

His hobbies were “woodwork” and “Coll.[ection] of Mugs.” He liked hunting and “track” and played baseball and hockey. He started school at age 6 and had “lst year High School” (1934) and “2 years Voc. School” (1937) in Saskatoon. His army files are more specific; he took a course in “Mechanics + diesel Engineering” at Saskatoon Technical Collegiate, Saskatoon, from 1934 to 1936 but did not complete it. While in Saskatoon, he served as a gunner in the 21st Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery, from 1936 to 1937. Although the chronology is unclear, he took a trade apprenticeship as a “Parts Man” and completed it. What is clear is that he worked as a manager of automotive parts from 1936 to 1942 with Northern Auto Parts Ltd., Melfort, and “Tractor Repair Parts,” Regina. He hoped to be a “Car Dealer” after the war.

“happy couple”

Presumably, Gooderham met his future wife at Northern Auto Parts, where she worked in the office for her father, George R. Alexander McConnell (1887-1963), “a pioneer business man of Melfort” who owned the company. Gooderham married Gwendolyn Olive Myrle McConnell (1916–65) on 2 April 1939 in Melfort, Saskatchewan, at All Saints Anglican Church. The local newspaper reported that it was a “pretty wedding” and the “bride looked charming.” After the reception, it was reported, the “happy couple left for Saskatoon where the honeymoon will be held. On return they will reside in Melfort.” Gwendolyn was the eldest daughter of George McConnell and his wife, Myrle Eliza Payne (1892–1937). She was born in Minnesota and married George on 5 January 1916 in Saskatoon; they had three daughters.

“figured he would be called anyway”

Coningsby and Gwendolyn Gooderham had one child. Their daughter, Myrle Margaret Gooderham, was born in Melfort on 7 November 1942. Coningsby Gooderham enlisted in Toronto on 9 April 1943 because he “figured he would be called anyway.” At the time, he was “manager Tractor Repair Parts” in Regina and lived at 360 Leopold Crescent, which he owned; he was one of the few among Argyll ranks who owned his own property. At some point after he joined up, Gwendolyn and his daughter moved to live with her father in Melfort.

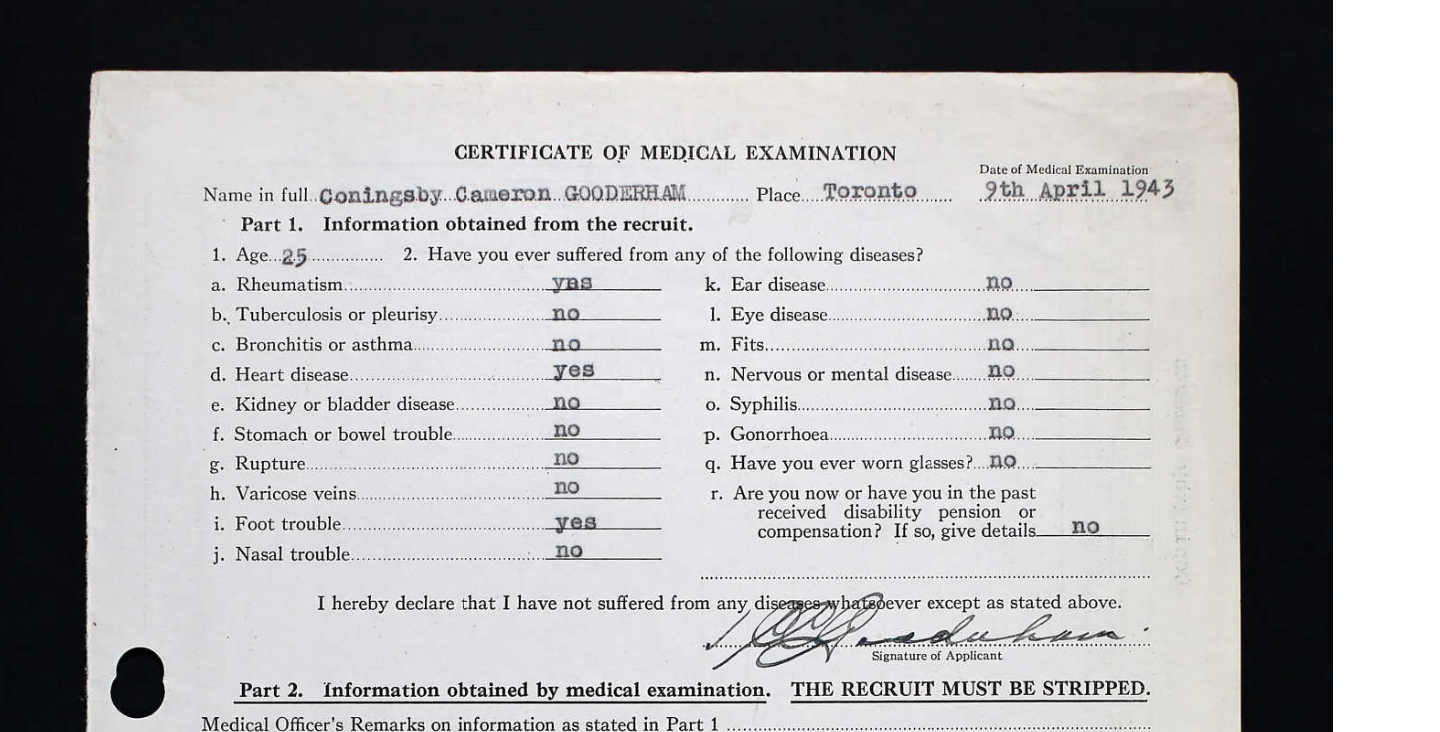

“a favourable appearance and an interested, cooperative attitude”

His health was generally good, although the medical examiner noted that he had suffered from rheumatism, heart disease, and foot trouble. He had an appendectomy in 1941 with “good result” and had cut his right foot in 1942, leaving “numbness two outer two toes, no disability on walking etc.” He had injured his right shoulder “on baseball – each year – has weakened shoulder.” The army examiner reported:

This recruit is a well-built … pleasant-mannered man and seems to have normal stability. He has a favourable appearance and an interested, cooperative attitude. Married with one child, he seems to be socially well-adjusted. He is fairly heavy drinker. A brother is in the R.C.A.C.

He is active in sports, playing baseball and hockey with city leagues and is very fond of both large and small game hunting. He has six rifles and shotguns.

Gooderham has above-average ability and seven years experience in automotive parts stores work. He wishes to follow this line of work in the Army and claims to have passed an Army trade test as a storeman. His experience should be of value to C.A.C. (Others), and he may develop into N.C.O. material.

Gooderham’s education, his work history, and his hopes for the army pointed to an army trade and the officer’s recommendation reads appropriately: “C.A.C. (Others) Trade Training. (Clerical Group.)”

Pte Gooderham transferred to #20 Basic Training Centre in Brampton on 30 April and was taken on strength there on 1 May. He was promoted acting lance corporal on 1 June. After the completion of basic training on 15 June he was promoted:

… to instructional Corporal and was highly spoken of by his Company Commander. At his own request is being allocated to Infantry and he made a special request to be considered for re-inforcement to 48th. Highlanders of Canada.”

On 10 August, the examiner changed the recommendation to infantry “Non Tradesman.”

Stability is good … Ambitious, eager.

Granted embarkation leave from 12 to 19 August, Pte Gooderham reverted to the rank of private at $1.40 per diem. On 26 August, he was at the #12 Transit Camp in Windsor, Nova Scotia. He embarked on 13 September and disembarked seven days later in the United Kingdom. He was interviewed on 28 September 1943 at #4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU). The army interviewer noted that he was 6’, 1”, 180 lbs. with blue eyes. His father’s “Racial Origin” was “Welsh” and his mother’s “Scotch.” The interviewer recorded that he was “Quiet, mature” disposition, a “Neat” appearance, and “Well built”:

Stability is good. Learning ability is somewhat above average. Manager of Auto motive Parts Store – for cars, tractors, trucks (7 yrs. Experience). Is ambitious, eager.

The interviewer’s first recommendation for possible army employment was “RCOC [Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps] – technical storeman spare parts (potential).” The second possibility was “Inf – Potential NCO.”

“the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment”

On 17 October, Gooderham received a pay hike to $1.50 per diem, the full regimental rate; on 29 October 1943, he was struck off strength of at #4 CIRU. The Argylls took him on strength the following day at Riddlesworth Camp. Posted to B Company, Gooderham was with the unit on 1 November (reveille was at 0500 hours) as it moved out on a four-day brigade-level exercise – Bridoon – in the field. At the end of the exercise on the evening of the 4th, the Argyll camp “assumed something of the festive air of a summer resort.” Flames from bonfires knifed “holes in the surrounding darkness” and “singers, accompanied by mouth organs … blended with one another from different sections of the grove.” “Argyll sing-songs have,” the war diarist observed, “a peculiar character of their own … from Scottish ballads to Jamaican folks sings … sprinkled with the popular ditties of the day.” “Abetted by the soft glow of a camp fire they have a quality that perhaps best expresses the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment.”

“new environment”

After reveille at 0430 hours, the Argylls made “our long trek south” reaching their destination, the town of Uckfield in Sussex. The various companies were quartered in local large manor houses. B Company was in “The Rocks,” within a five-mile radius of the town. The “new environment” was “an instant hit with everyone concerned. And since we are only 16 miles from the English Channel the Regiment feels that much more close to the theatre of war.” Searchlights “probed the darkness” and anti-aircraft guns could “be heard in the still of a night.” On rare occasions, they could hear German planes. Weather forecasts were for “clear and cold” with the emphasis on the latter. Complaints abounded about the quality of “English heating and plumbing equipment,” and the rifle companies concentrated “chiefly on conditioning work.” There were leaves, and on 19 November the Argyll Pipes and Drums played “Retreat” for the first time since arriving in England.

“every race, creed and condition have been poured into the melting pot from which is brewed soldiers and Argylls”

The tempo of training increased and on 1 December the war diarist opined that with “time and the nature course of events, the personnel [and] the character of the Regiment is changing.” Old faces left and new faces arrived. “Lucky” was the rifle company that “can boast of having over thirty ‘old originals’ on their roll.” “Stalwarts from all parts of the Dominion … of every race, creed and condition have been poured into the melting pot from which is brewed soldiers and Argylls.” Lt Don Seldon, the Adjutant, thought “they all integrated pretty well.” There was continued work on the ranges, incessant effort upon conditioning, and a hardy diet. In early December, the battalion was in the field again with personal discomforts such as sleeping on the ground “augmented by a steady drizzle of rain.” On 11 December, the “usual rain routine” was varied “with a light fall of snow.” The Christmas season included parties for local children, movies, short talks, and especially good meals on Christmas day, with the officers serving and Lt-Col Dave Stewart dispensing “beer with professional skill and a surprisingly steady hand.” Several Argylls commented that nearly everyone received parcels from home. The new year brought new equipment, more training, inter-Regimental boxing competition, and more work on the ranges, which were “doing a thriving business. All companies are spending a goodly portion of their time riddling targets with speed and accuracy.”

When the unit entrained at Uckfield on 14 February for amphibious training in Scotland, Gooderham attended a “CMHQ Crse 500” from 14 February to 4 March 1944. In early March, B Company lost Lt John Lloyd Johnston, the company’s “pepper-potting enthusiast” to the newly formed Scout Platoon. There were leaves, and Argylls made use of them to visit London. Gooderham was appointed acting lance corporal on 7 April 1944. On 24 April, the unit practised river crossings and night assaults. A mobile bath unit provided hot showers on the 28th; they were, the diarist reported, “most welcome.” There were battalion parades and inspections as well as visits by various dignitaries. As for the “general trend of trg,” it consisted of “hardening exercises, route marches, short five mile speed marches. Whenever possible, coys and sqns of tks combine their trg in ‘Infantry cum Tanks’ tactics.” D Day increased the anticipation of battle. Gooderham became acting corporal on 14 June; preparations for the move to France became the focus of unit activity, interspersed with range work and two-company exercises.

“to the tune of ‘Johnny Cope’ on the bagpipes”

Gooderham embarked for France on 19 July 1944 and disembarked the next day. Reveille on the 28th was 0600 hours “to the tune of ‘Johnny Cope’ on the bagpipes.” The Argylls were “being eased into a holding position” and moved through Caen. CSM George Mitchell of C Company wrote in his diary: “Caen smashed – leaves one with hopeless feeling – utter devastation.” Pte Albert Clare Huffman, B Company, “always remember[ed] the rubble and the destruction … really made an impression on what war was really like … just completely demolished, it was unbelievable.” The next day Pte Percy Samuel Hindle and Pte William Daniel McCann were killed by enemy shelling. Mitchell noted the effect of the first battle casualties: “realize that it’s war.” The unit moved to a position at Bras on the 30th and then to Bourguébus on 2 August. There were more casualties there from intense shelling and sniper fire, including Pte James Bannatyne. As Pte Tom Sayer, B Company, recalled it, the night move across a battlefield meant “you’d be stepping on these bodies and they’d been in the sun, and gas coming out. That wasn’t too good.” Bourguébus “was almost a complete shambles.” B Company along with A took up “forward” positions on the town’s perimeter. The shelling, Mitchell recorded, was “terrific.” Heat, dust, flies, “no sleep for some time,” shelling, and snipers made life miserable. The sniper fire was “rarely accurate, but it was persistent and demoralizing.”

“engaged on three sides by very intensive Small Arms and Mortar fire”

The unit was at Bourguébus on 5 August when it received orders to take Tilly-La-Campagne:

…At 1530 hours word was received from Brigade H.Q. that Tilly had been evacuated … and we were ordered to send a platoon forward to occupy it. The authenticity of this report was questioned, inasmuch as somebody still in the area … was continuing to engage our area with Small Arms and Mortar fire. Nevertheless, a Platoon of B-Coy, under the command of Sgt. McLaren, was ordered to occupy Tilly.

The platoon left at 1630 hours and by 1700 hours was seen to enter the village … At the same time they were engaged on three sides by very intensive Small Arms and Mortar fire. It was appreciated by the C.O. that Tilly was still occupied in force and that this platoon would have to withdraw. He therefore ordered a heavy concentration of three Artillery Regiments on known enemy locations. With this help and the assistance of very heavy mortar fire, the platoon commander succeeded in bringing back 23 of the original 30 men. In this action, Pte. Ed Purchase sacrificed himself fearlessly in order to cover the withdrawal of the remainder of his section. When last seen, he was advancing towards the enemy firing a Bren gun from the hip, thereby facing certain death [in the event, he was captured unharmed].

“a guy by the name of Gooderham … Yeah, he was killed”

This action proved fatal for ACpl Gooderham and Pte Bill Wingate, also of B. The latter died of wounds sustained that day but in a separate action. Pte Bruce Johnson, a sniper in B, recalled the incident that resulted in Gooderhams’s death:

[I knew very well] … a guy by the name of Gooderham. He was in B Coy, a corporal … if I remember right. Yeah, he was killed. He … had a section with him. I think they went out and ran into a machine gun nest. I think there were four or five went with him that were killed…

The day’s various actions at Tilly resulted in more deaths, including Pte Joe Carlton of C Company. The battalion had: 18 killed, 17 wounded, and 1 POW in its first battle. Maj Hugh Maclean judged the Argylls’ first battle as a failure. It was a heavily fortified village manned by crack German troops and “probably the most serious obstacle the Argylls ever engaged.”

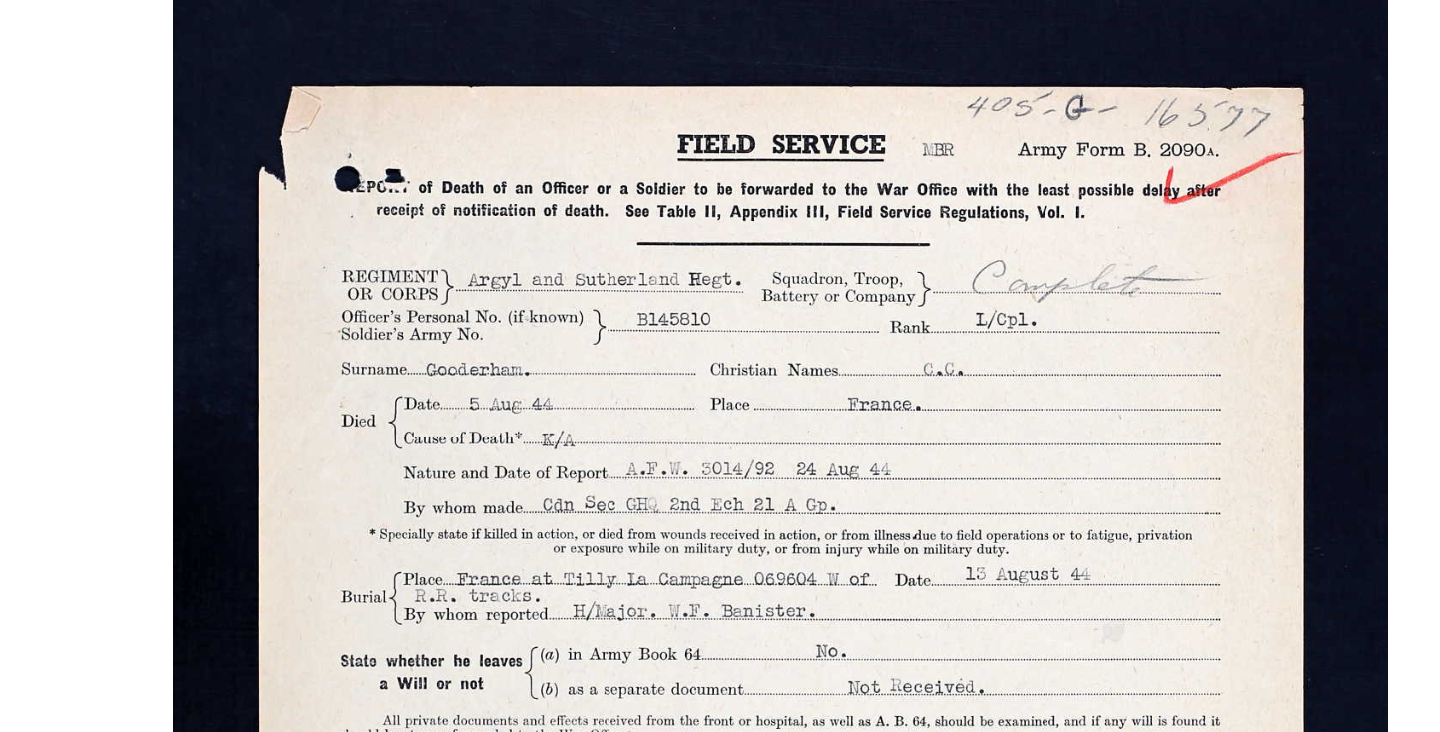

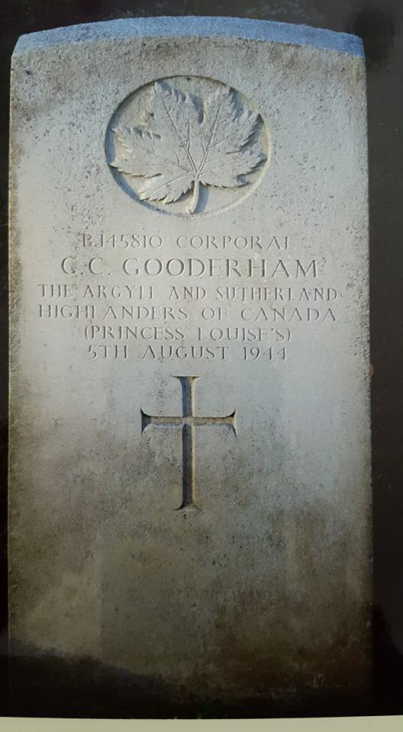

At Tilly, the Regimental Aid Post (RAP) (see Pte Richard McDonald) and the Regimental padre, HCapt Charlie Maclean, began their wartime work in earnest. The stretcher-bearer thought Pte Wingate was just wounded and he was brought to the RAP dead. ACpl Gooderham was almost certainly killed immediately. Maclean buried him at Tilly west of the “R.R. tracks.” There was typically a short service and a Regimental piper played the Argyll lament “Flowers of the Forest.” The padre collected anything personal in the battle dress. Coningsby Gooderham left little by way of personal effects: a “photocase,” some snapshots, 2 photographs, and his identity bracelet.

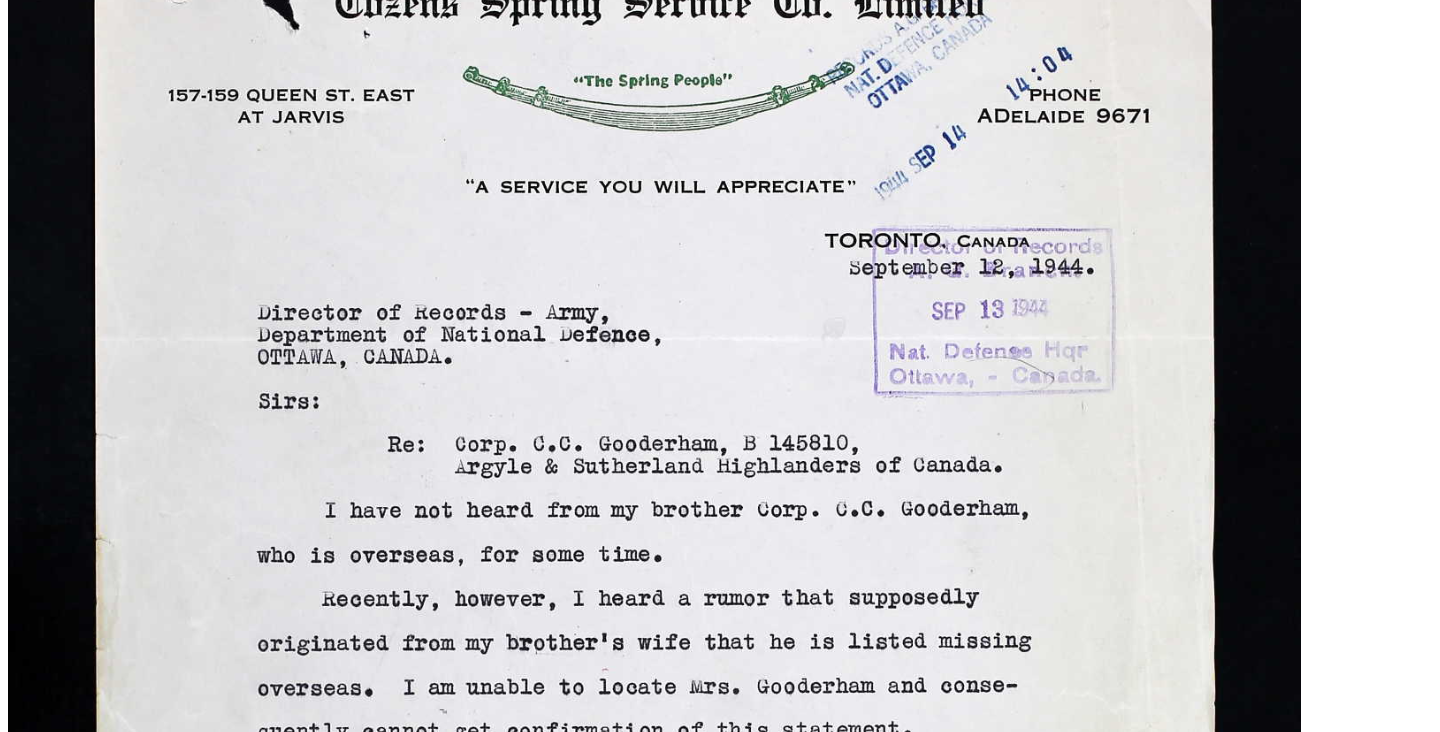

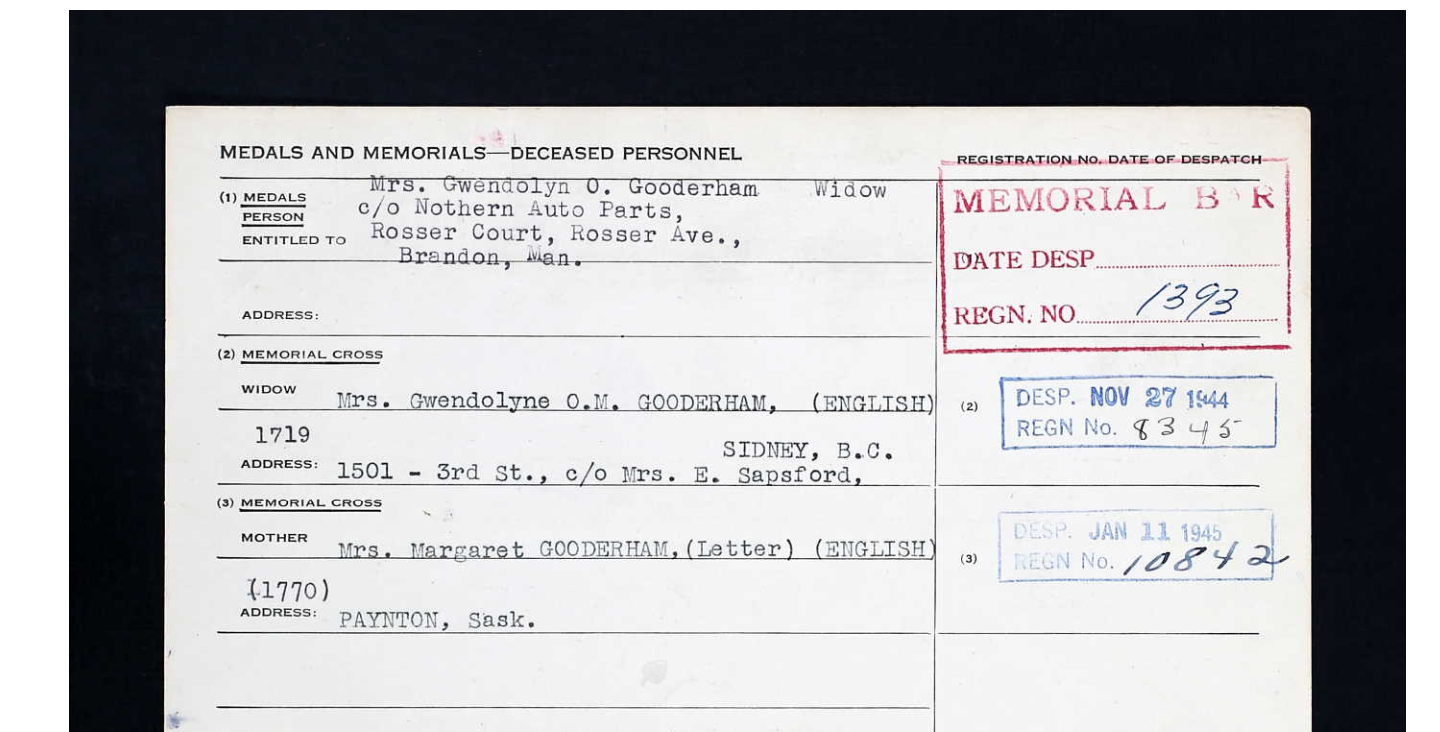

“unable to locate Mrs. Gooderham”

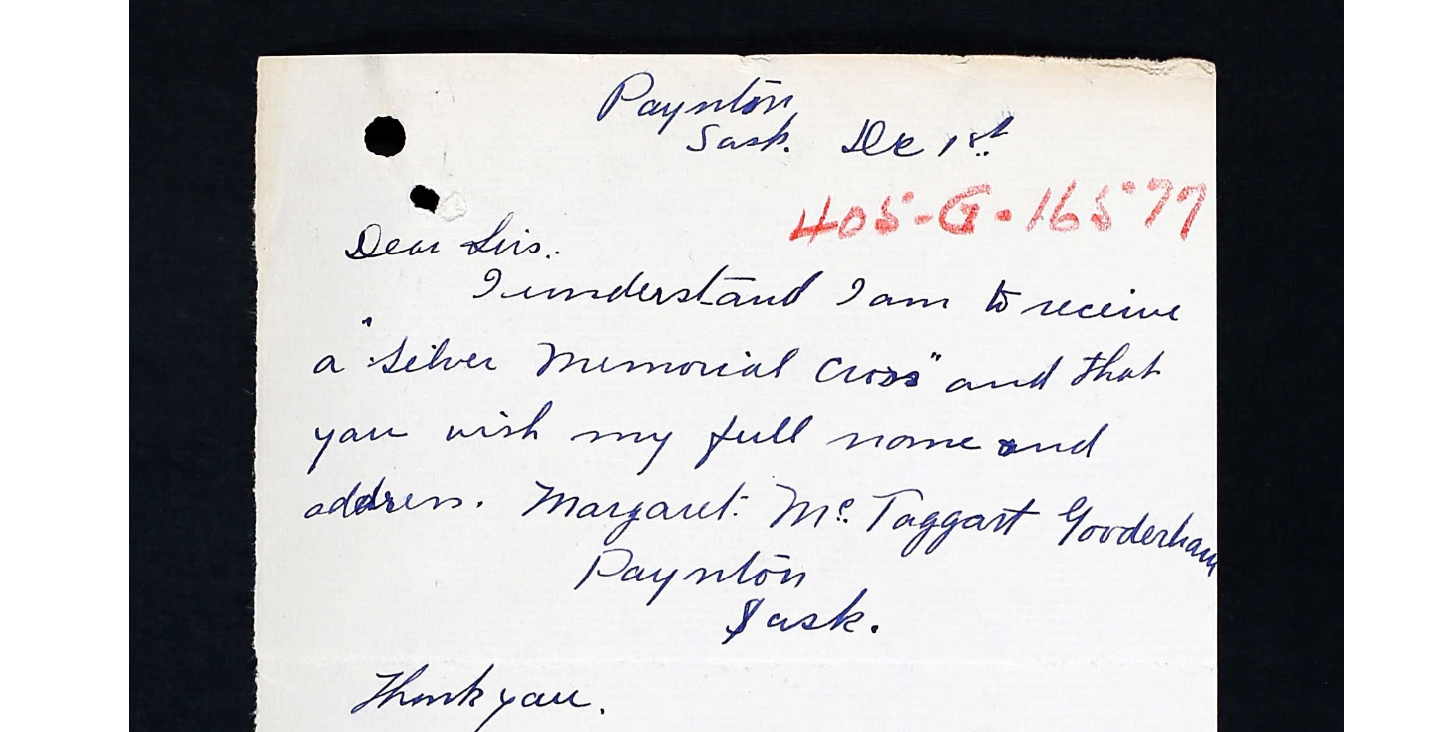

His brother, Schuylar Horace Gooderham, wrote to the Director of Records on 12 September 1944 about Coningsby: “I heard a rumor that supposedly originated from my brother’s wife that he is listed missing overseas. I am unable to locate Mrs. Gooderham and consequently cannot get confirmation of this statement.” In the papers for his army estate, Gwendolyn Gooderham declared, “I do not know the specific addresses or ages of various members of his family which can be obtained from his mother Mrs. Margaret Gooderham 414 10th St Saskatoon, Sask.” The Dependents’ Allowance Board queried the Paymaster General’s office to “be advised … who is to receive war service gratuity for the benefit” of his daughter. At the time of his death, an allowance of $20 was being paid to his widow.

“My Dad’s death made my mother go a little crazy …”

Gwendolyn Gooderham’s life was in disarray by the time of her husband’s death. Daughter Myrle Mackenzie did “not know his [her father’s] family.” They moved to the United States shortly after her father’s death. She had a half-brother born in November 1944 to a “different father.” “My Dad’s death made my mother go a little crazy … she went a little nuts.” “I didn’t know I had a Dad other than my step-father. I didn’t know until I was 11.” It was “crazy … we never went to Canada.” “My mother got into trouble with her family and her father disowned her.”

On 16 July 1946, the district administrator in London wrote to the Canadian Pension Commission on behalf of Flight Lieutenant Brian H.N. Reid of the RAF. He trained in Canada and while there “he married a Mrs. Meyrle [sic] Gooderham (nee McConnell) on the 16.2.1944 at Regina.” She “was supposedly the divorced wife of” L/Cpl C.C. Gooderham. Shortly after, Reid was posted to India, where he heard “through private channels that his wife had never been divorced, that Gooderham was killed in action on the 5th August 1944,” and that later she received a widow’s pension. Unable to contact her, “who he understands, moved to the States,” Reid was “anxious to know whether his wife was competent to marry and whether he can obtain an annulment of the marriage.” He “knows nothing of his wife’s antecedents nor can he get in touch with any of her relatives.” He knew his wife had employed a lawyer, R.M. Balfour of Regina, and wrote to him “but has had no reply.” The commission sent its reply on 17 August 1946, acknowledging that “this is a problem case, and it is difficult to know just what reply should be forwarded.” The commission had not located her and there were no claims for herself or her child. It attached a copy of a memo in which “there were several references to one Brian H.M. Reid of the R.A.F., and mention made that Reid married during his sojourn in Canada and the United States – being the father of a child born in October 1944. Apparently, Mrs Gooderham “suggested that it was her cousin in the United States who was to marry Reid.” Nothing, however, was definitive. As for the Commission, because “no payments are in issue … it is not greatly concerned at this time.”

“seemed like she had problems even when young, undiagnosed”

Myrle met “one of my mother’s sisters about 20 years ago.” Luceille Eleanor Jerome (née McConnell) (1919–2013) played hockey, attended university, received an accounting degree, worked at Northern Auto Parts (as did Gwendolyn) and married Ralph Jerome in 1942. Based on information from Luceille, it “seemed like she [Gwendolyn] had problems even when young, undiagnosed.” Myrle says that George McConnell “wanted Mother to give me to my grandparents and that’s why she left and she was pregnant and that’s what he didn’t like but who knows if it is true.” “He was a difficult person as a father, but she did something wrong,” possibly in relation to the family business – “I learned that from her sister.”

Hockey team in Melfort, Sask., 1936. Gwendolyn McConnell is 2nd from the right.

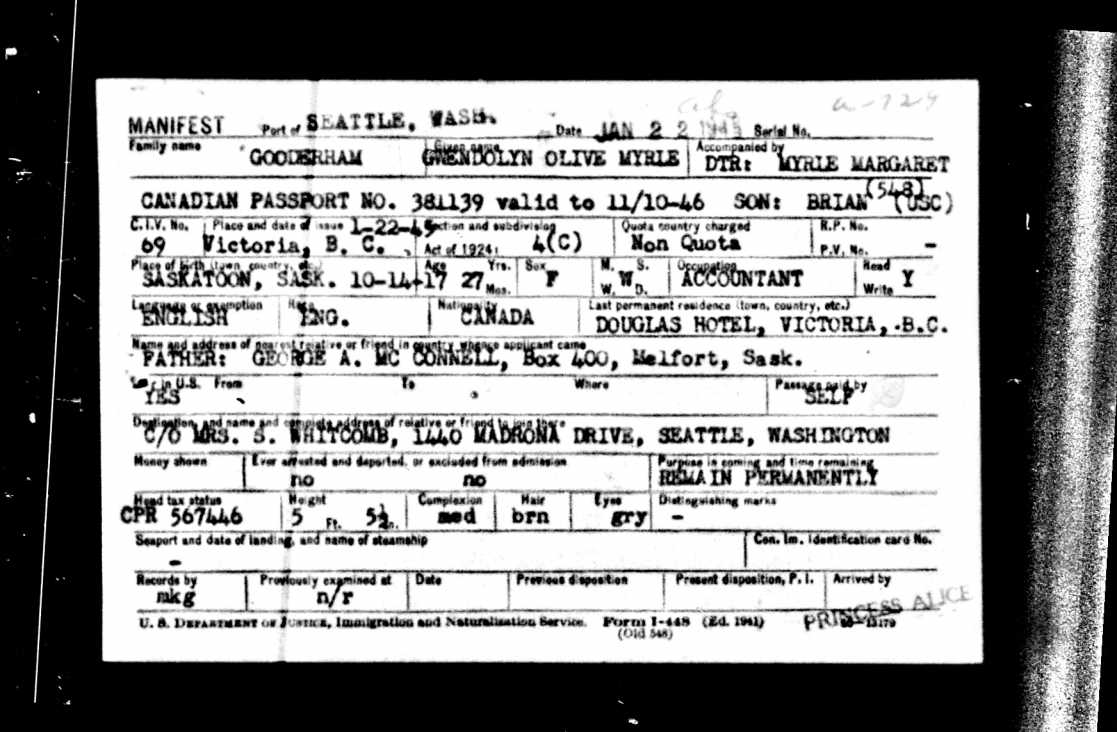

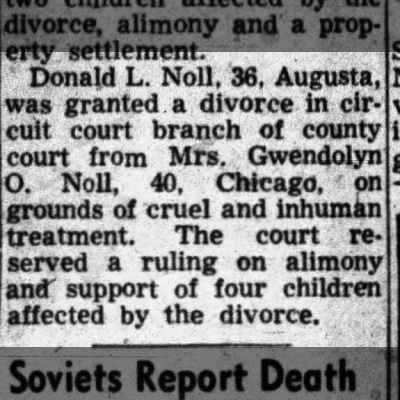

Gwendolyn left Melfort in 1944. By November she was staying in Sidney, British Columbia, with her paternal grandmother. She declared her intention to become a naturalized American citizen on 5 December 1944. When she crossed the border in January 1945, the border-crossing form listed her last permanent address as the “Douglas Hotel” in Victoria and gave her occupation as “an accountant.” The Golden Glint Company in Seattle, Washington, requested “permission to import” her. She met and married Donald Lehnhoff Noll (1921–90), an American veteran, in 1946; in August that year, they had a child who died the same day.

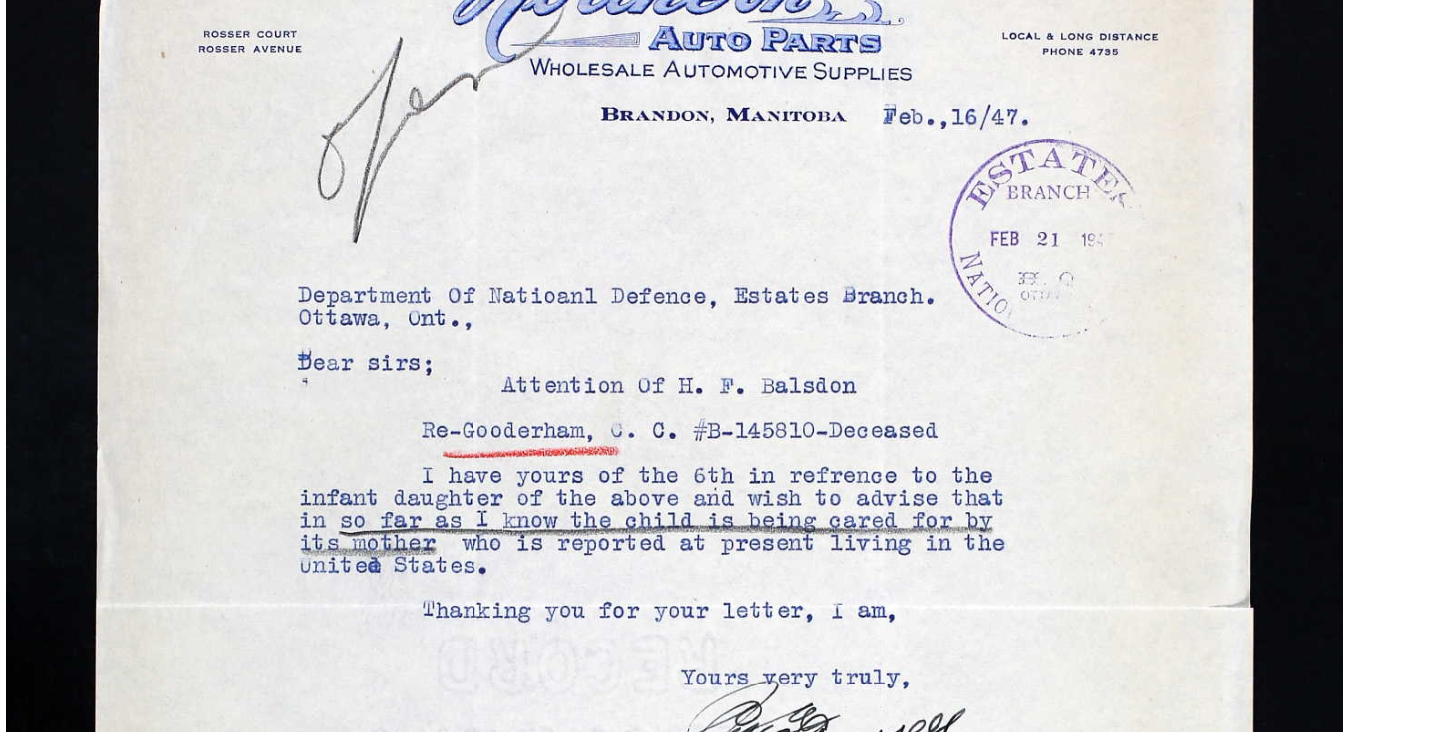

G.A. McConnell of Northern Auto Parts wrote to the estates branch of DND on 16 February 1947:

I have yours of the 6th in reference to the infant daughter of the above [C.C. Gooderham] and wish to advise that in so far as I know the child is being cared for by its mother who is reported at present living in the United States.

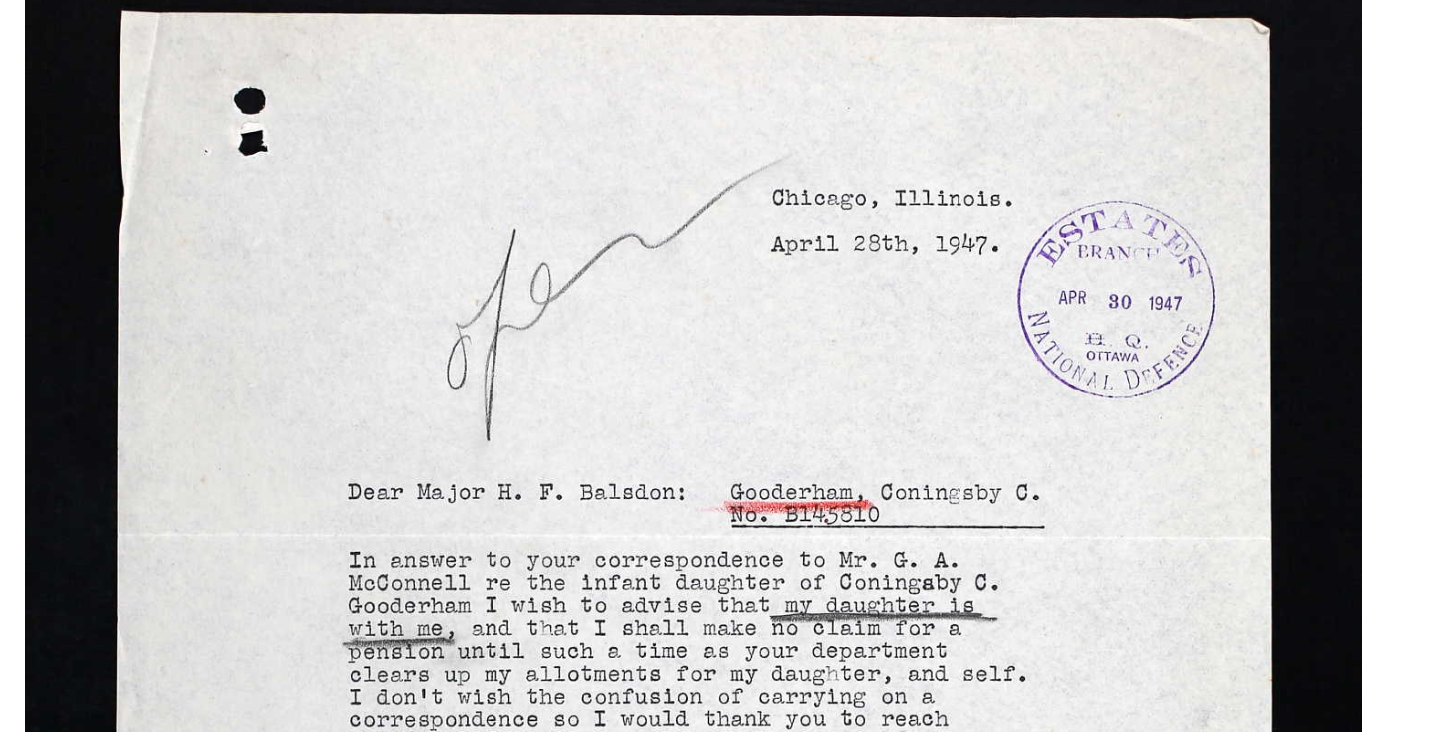

Gwendolyn Gooderham wrote to the estates branch in response to her father’s note, which advised “that my daughter is with me, and that I shall make no claim for a pension until such a time as your department clears up my allotments for my daughter, and self. I don’t wish the confusion of carrying on a correspondence so I would thank you to reach a decision concerning my back pay, and then at that time hear from you.”

“It’s a sad thing [not knowing her father], the older I get the more I think [about it]”

Daughter Myrle Mackenzie did “not know his [her father’s] family.” They moved to the United States shortly after her father’s death. She had a half-brother born in November 1944 by a “different father.” “my Dad’s death made my mother go a little crazy … she went a little nuts.” “I didn’t know I had a Dad other than my step-father, I didn’t know until I was 11.” It was “crazy … we never went to Canada.” “I wondered about my father’s relatives. My mother got into trouble with her family and her father disowned her. I still don’t know who my relatives are on his side. I did have one picture,” but my “family was so dysfunctional, I lost everything. I have no pictures.” I “found out [about her father] in a bad way. Mom was really angry at my step-Dad and told us.” “We’re [Myrle and her siblings] all doing well.” She “had problems with severe migraines, always worked, [she was] dependent on medications and slowly became an active alcoholic, my step-Dad was an alcoholic.” “It’s a sad thing [not knowing her father], the older I get the more I think [about it],” and “it makes me sadder.” “We moved to a family farm in Wisconsin, [when she was about 13 or 14] and up in the attic was a lot of stuff, her [her mother’s] letters from my Dad and her letters to him and letters from his brother.” “That’s when I figured out my brother had a different father.”

“I think about him a lot … The image I hold is of him in his uniform”

Myrle considers her mother “smart, very smart, pretty much brilliant.” She thought she was a chartered professional accountant but is unsure: “a lot of things told by Mom [were] not true – for some reason.” She worked as an accountant and “things went good in Wisconsin until they fell apart.” The family moved away, then moved back, but things “spiralled down” and they “lost” the farm about 1958. When she was “about 19 or 20,” she “tried [unsuccessfully] to get financial assistance” from Veterans’ Affairs in Canada. “The man I married, his father [was] also killed in the war.” “I think about my father more now, the older I get, the more I think about him. When I was young I was in survival mode.” There are “lots of marks in the road travelled and forks in the road, I think about him a lot but – life.” I “remember a picture of him with my mother. The image I hold is of him in his uniform.”

“She told his name, he was killed, and we never talked about him again”

When they lived in a small town, it had an “ice rink and she [her mother] put on hockey skates, she was an amazing skater.” “My half-sister tried to find his grave but couldn’t but I never went to France.” “You know I grew up in a time you didn’t really talk to parents. I was told what to do but I never really talked to her. She told his name, he was killed, and we never talked about him again.”

“My kids know about my life, but not very much.”

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Note: ACpl Gooderham’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy for the Field of Remembrance.

Main Street, Melfort, Saskatchewan.

Myrle, daughter of Coningsby Cameron Gooderham and Gwendolyn Olive Myrle McConnell.

Myrle with her mother, Gwendolyn.

Myrle with her half-brother, Brian, her mother, and her stepfather’s mother, Mrs. Noll.

Gravestone, ACpl C.C. Gooderham.