Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Note on Revised Post: More Information on Pte Jones

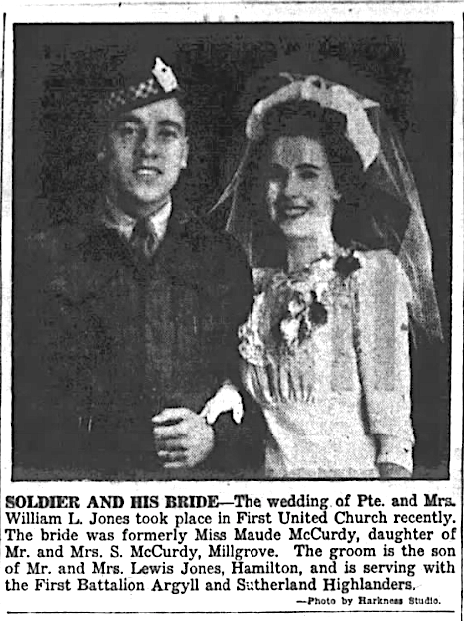

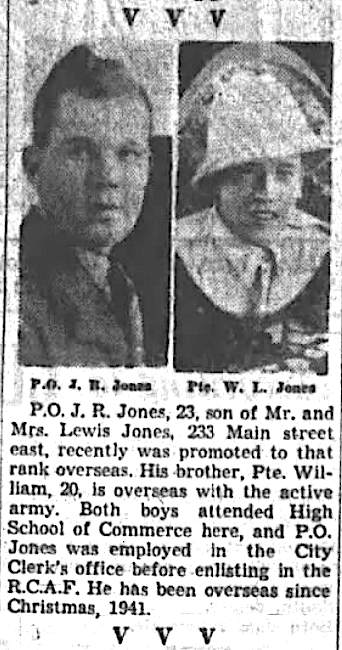

In 2021, I lamented my inability to find an image of Pte Jones. Recently, I received two images for him, which have been added at the top right of this page. Earlier this month, I received a welcome email from Elaine Archer with photos. She explained that her husband, David Archer, had discovered them:

David is working on a project he calls Operation Picture Me. He looks through on-line newspapers searching for articles about the soldiers who went off to war and did not come home. He sends copies of the articles to the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and Find-a-Grave. He noticed a link to William Jones’ Argyll history page posted on Find-a-Grave. He checked the history page and saw that you did not have a photo of William.

The Hamilton Spectator is now digitized and David Archer has used it in his noble efforts. I offer my thanks to him and Elaine for contacting us.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

29 July 2024

Introduction

The work on the Black Yesterdays project in the 1980s and early 1990s introduced me to the veterans of the 1st Battalion. Often their memories became mine, as was the case with Pte J.N. “Mac” MacKenzie, D Company. Cpl Harry Ruch, A Company, also etched his thoughts in my memory. In Harry’s case, it was his private diary that did the etching. Bill Jones was also in A Company and Bill Jones was the company’s first casualty in battle, a death that weighed heavily on Cpl Ruch.

Again, I was unable to find an image of Pte Jones. I am hopeful that the pages of the Hamilton Spectator will yield one once the Special Collections Room of the Hamilton Public Library reopens again. When it does and if there is an image, we will add it to Pte Jones’s biography. To date, I have not found any family. I offer my gratitude to Ben Dyment, Archives Technician, Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board Educational Archives, who provided helpful, full, and timely responses to my frequent queries.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte William Lewis Jones (1923–44) (B 46590)

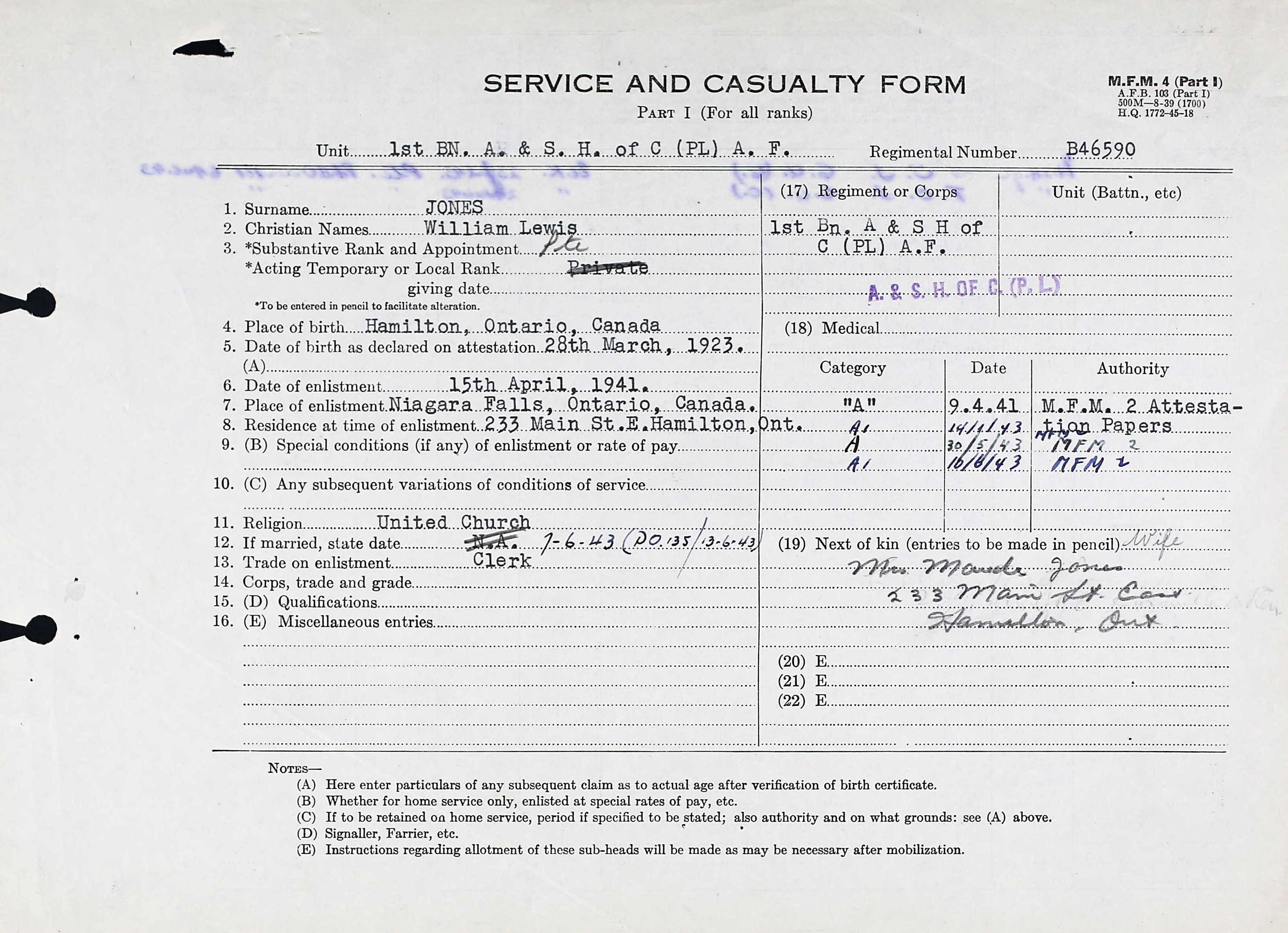

KIA 8 August 1944

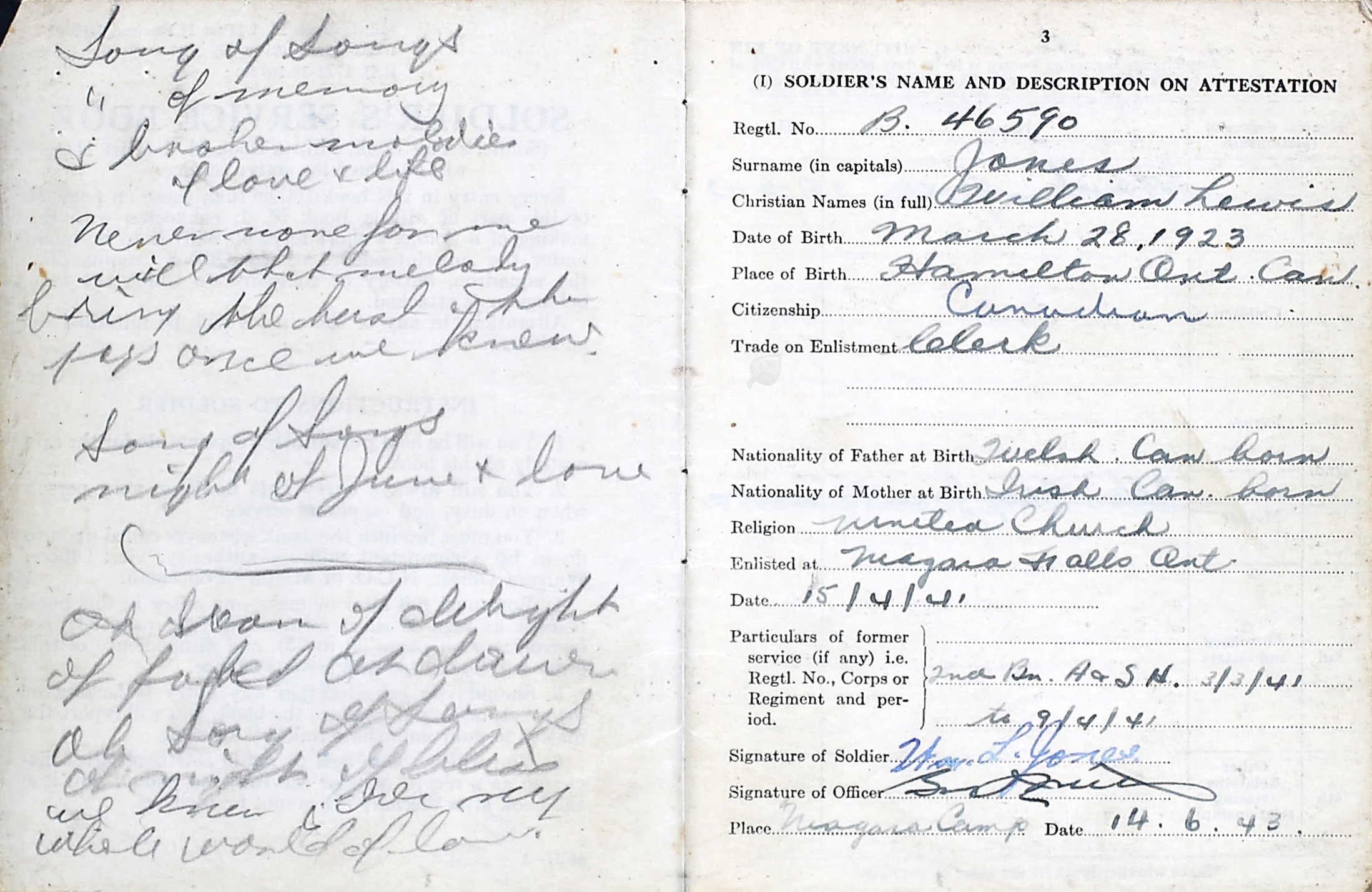

Pte William “Bill” Lewis Jones was born in Hamilton on 28 March 1923, the second son of Lewis Spring Jones (1900—76) and Ellen May Mulligan (1901—87). In his Soldier’s Service Book, Jones noted that his father was “Welsh. Can born” and his mother was “Irish Can. Born.” They married in Hamilton on 8 May 1919. Lewis Jones was of Welsh origin, a Presbyterian, and a carpenter; in 1921 the family lived at 50 Gore Street (where Bill was born), a brick house that they rented for $35 monthly; Jones’ yearly wage was $720. Bill attended school from the age of 5 to 17, and had “3 years High school” “commerce/clerical work” as of 1939. The school in question was Central High School of Commerce. Prior to enlistment, he had been a store clerk for 1 year, a bookkeeper for 6 months, and a riveter in a factory for 3 months. He worked as a clerk for the lawyers Mewburn & Marshall at enlistment; he did not wish to return there upon discharge. He had no plans for that future period other than an ambition to join the “Permanent Army.”

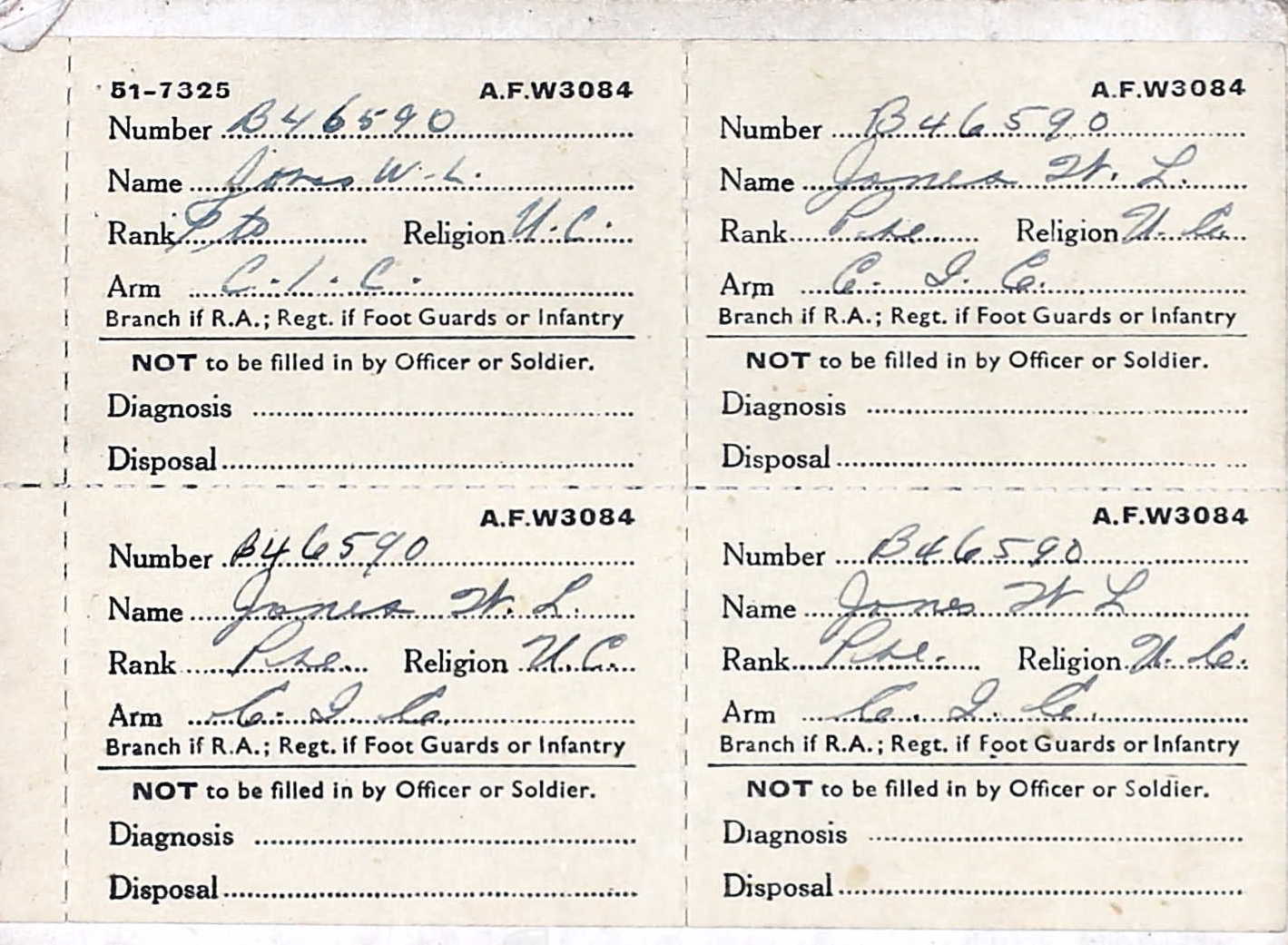

Soldier Service Book, Pte W. L. Jones.

“Duty”

His older brother, John Richard Jones (1920-2007), had joined the RCAF and was stationed at Gibralter; Bill Jones enlisted at Chippawa Barracks on 15 April 1941; in 1944, he gave his reason as “Duty.” He had served with the 2nd Battalion of the Argylls from 3 March 1941 to 9 April in the “Pay office.” He was 5’, 7½”, 135 lbs, with a “dark” complexion, brown eyes and black hair. He had pleurisy and worn glasses for six months. The army examiner offered this appraisal:

A well-built athletic young man of average size … He is well above average intelligence and posseses [sic] a keen alert mind as well as a courteous pleasant manner. This man is desirous of getting married in the very near future. He seems to be emotionally stable and has adjusted well to the army. He plays most sports including lacrosse, rugby and baseball. This man should prove to be N.C.O. material and warrant promotion.

The recommendation was: “Inf. (others) – Rifleman. Possible N.C.O. material.

Pte Jones was posted to A Company and remained there for the duration of his service. He had a brief one-month stint as batman to Lt George Mills in June 1941. During his time in Hamilton, at various spots on the Niagara peninsula, and at Camp Nanaimo, British Columbia, Pte Jones maintained a spotless “crime sheet” as army examiners often called it. This period of military innocence ended on 22 December 1941. Pte Jones was “found beyond camp limits.” Capt John A. Farmer awarded him 7 days CB (confined to barracks” with “(no forf)” [forfeiture of pay]. Moreover, he “wore no identity discs.” It marked the burgeoning of misdemeanours. He was AWOL on 8 February 1942 (2 days CB) and on 8 March (10 days CB). Jones then varied the pattern. He was awarded 10 days CB on 3 June 1942 for failing to appear on parade and failing to comply with an order. He returned to previous form on 5 July (AWOL – 7 days CB). Change was the order of the day for his crime sheet: 31 July, failure to comply with an order (7 days CB), and on 30 October Lt Bob Paterson found him “improperly dressed” (3 days CB). While in Jamaica, he was hospitalized on three occasions: 5 days in August 1942 for dengue fever, 18 days from 25 September to 12 October for “Gonorrhoea Fresh,” and 7 days in April 1943 for bronchitis. On 1 January 1943, he received an increase in his daily pay to $1.50, the full regimental rate. He received 14 days confined to barracks in March 1943 for being AWOL.

“desirous of getting married in the very near future”

The Argylls returned from Jamaica to Camp Niagara in May 1943. Pte Jones received a furlough from 1100 hours from 1 June to 10 June 1943. Having made his proclamation of desire in 1941 and having made it sufficiently compelling to impress an army interviewer, Bill’s wish was not to be. He spent 5 months in Nanaimo, British Columbia, in 1941 before the Argylls shipped out to Kingston, Jamaica, for 22 months. Back in Canada more than two years later, he wasted no time in making “the very near future” immediate. He married Maude McCurdy on 7 June 1943 in Hamilton; she took up residence with his parents at 233 Main Street East in Hamilton (where Bill was living when he enlisted). Marriage necessitated permission by the army, and it was given after the fact on the 13th. He received a three-day furlough from 21 to 24 June, which, presumably, he spent with his wife. If the assignment of pay is a measure of love, Pte Jones was in love. He assigned $30 monthly to the support of his wife (his daily remuneration was increased to the regimental rate of $1.50 daily on 1 January 1943); $20 or $25 monthly seems to have been more usual for Argyll privates.

“of love + life”

The Soldier Service Books of Argylls killed in action rarely contain personal notations. The content is almost always prosaic, thus fulfilling the intent of its army designers. Occasionally, someone will jot down an address or two but rarely more. Pte Chris Jenkinson inscribed his book with a stanza from the “Skye Boat Song.” He was a rarity to be sure, a romantic inclined to irony and a source of befuddlement for army interviewers and examiners searching for the appropriate pigeon hole to put him. Bill Jones may well have shared that temperament. A young man whose hobby was “Sax & Clarinet,” he scrawled, in a seemingly hastily fashion, the parts – pertinent to him one supposes – of a song as well. Clarence Lucas (1866–1947) was a Canadian composer and lyricist born on the Six Nations Reserve and took leave of life in France. He wrote “The Song of Songs” in 1914; Perry Como performed it in an album of “Supper Club Favourites” in 1952. Was Jones attracted to the words of a “Night of June + love”? After almost three years of absence, he had mere days in June 1943 to marry before he left for overseas. He wrote:

Song of Songs

“ of memory

+ broken melodie

of love + life

Never more for me

will that melody

bring the heart and the

joys once we knew.

Song of Songs

Night of June + love

Oh dream of delight

of faded ardour

Oh Song of Songs

Oh night of bliss

When you were my

whole world of love.

What does one make of its elegiac quality? The June reference may suggest it was written after June 1943 by a young Argyll overseas and ardent for the “dream of delight of faded ardour.” The evidence does not take the reader very far, but it recommends some consideration of young Pte Jones as a romantic as was Pte Jenkinson.

The Argylls arrived in Scotland on 27 July 1943 and entrained immediately for Camberley in England. There were inspections, route marches, privilege leave (and an “information bureau” set up to help soldiers with planning it), medical examinations for “V.D. and skin disease,” a refresher on basic training, training at night, and preparations for the forthcoming unit inspection that would determine the Argylls’ fate (broken up for reinforcements or placed in the order of battle). The battalion “won a place in the 10th Cdn. Inf. Bde in the 4 Cdn Armd Div.” The unit moved to New Hunstanton in September where there were large field exercises and the arrival of the new commanding officer, Lt-Col J. David “Dave” Stewart. Pte Jones received seven days personal leave from 30 August to 5 September 1943 and rejoined the Argylls in their new quarters.

“blisters and blasphemy were common”

It did not last long, and on 1 October the unit marched to Riddlesworth Camp with a regimental piper preceding “each company as an aid to flagging feet, but blisters and blasphemy were common.” Here, there were movies, a canteen truck “that sells such things as cigarettes, cakes, et. Without benefit of ration tickets,” bingo, sing songs, and other organized entertainment. A brigade “scheme” on 7 October began “with a 20 mile route march at 1900 hours.” There were also dances with a “limited supply of whiskey and beer.” The tempo of training increased with more exercises often “in the drizzling rain.” Pte O.C. Taylor, A Company, complained: “The weather was terrible … Sometimes we were about ten days soaking wet. No fires … had to stay wet and miserable.” LCpl Gerry Beaudoin, A Company, thought: “We got some good training there … go on these massive schemes involving divisions and it’s rush like hell somewhere and stand around and wait for a day, and stand around and wait all night and then rush somewhere else.” In early November, the Argylls moved south to Uckfield in Sussex. The various companies were quartered in different locations. The weather was cold and the pace of training quickened. There was range work aplenty, trips to London, more rain, some snow, new weapons, and special meals and festivities to celebrate Christmas, including parcels from home.

All soldiers underwent interviews to evaluate their suitability for the next stage of service. Pte Jones’s turn came on 24 January 1944; the army interviewer estimated his skills as “Good.” He had worked in 1940 for three months at “Balfour’s Wholesale Grocery” in Hamilton, earning $12.50 weekly; as an office clerk at the law office Mewburn & Marshall for 3½ months, he made $15 weekly; he had been promised his job again after discharge [Sydney Chilton Mewburn was a Hamilton lawyer, politician, and militia officer; he had been minister of Militia and Defence from 1917 to 1920 under Sir Robert Borden]. Maude Jones’s attitude to the service was deemed “Good” and the status of his home in childhood described as “Harmonious.” He liked tennis, swimming, and shooting; he played hockey, football, and basketball.

“Settling down now”

During his time in the Argylls, his main duties were infantry training, garrison duty (in Jamaica), a clerk in the “Pay Office.” In 1943, he passed a three-week course on the “38 Set” [a British man-packed radio transceiver used for short-distance communication]. His deportment was judged “Poor,” his disposition “Earnest,” his grooming “Good,” his physical appearance “Strong,” and he was “Av[erage]” in map reading and military knowledge. Generally, he was:

Intelligent. Well built physique. Rather prejudiced attitude at present owing to failure to get prescription for glasses. Claims eyes are bad. M.O. promises examination. Poor adjustment to army at start resulting in considerable offence record. “Settling down now” he says. Home conditions satisfactory. No complaint.

The interviewer took note of Jones’s crime sheet and his response to it. Jones’s “poor adjustment” was not at the start; it came almost 18 months later and was concentrated in Jamaica. A written note on the form reads: Prescription for glasses? M.O.” Examined on 22 March 1944, the vision in his left eye was 20/30; his right was 20/100; it had been 20/40 in 1941; he needed glasses.

“we booed the piss outta him”

Training increased in the months leading up to D Day and the Allied invasion of France on 6 June 1944. Range work, 10 days of training in Inverary, Scotland, more inspections, a street clearing exercise in London, schemes on the “Downs” of Brighton (“just feeling absolutely filthy dirty” was how one officer in A Company described it), more tours of London, and on 28 March “another generous serving of entertainment dispensed by the Canadian Army Show … a hot swing band, pulchritudinous girls and first rate gags.” On 6 April, A Company did a “coy ex on approach, contact and encounter.” There was increased censorship that month and “the men were very upset – which is a mild way of putting it,” according to Capt Jack Harper of A. By early May, the “general trend of trg consists now of hardening exercises, route marches short five mile speed marches.” Prime Minister W.L.M. King inspected 4 Division on 17 May. Capt Bob Paterson was bitter. The battalion waited for “an hour and a half before he arrived in very cold weather, and he arrived in a coonskin coast and fur hat out from a limousine.” Cpl Tommy Dewell, the Falstaffian character of D Company, was a tad harsher: “we booed the piss outta him … we stood there for hours in the goddamn rain before he ever showed up, and all he got was boos.” The battalion moved to new billets on the 19th, and on 21 May 1944 Pte Jones forfeited 7 days pay for being AWOL.

“the uncertainty”

At the end of May, A and C companies were “firing rifle and Bren practices on Hawkenbury Ranges.” On 6 June Pte Harry Ruch, A Company remembered being “down in southern England waiting as a company.” “We knew that we were going over soon. Of course, we weren’t part of D-Day, and so were were doing route marches.” “The thing … that’ bug you the most,” Capt Jack Harper of A Company recalled, “was the uncertainty.” Pte Jones embarked for France on 21 July; he disembarked two days later.

The Argylls gradually moved to the front. The signs of destruction were everywhere along with death, stench, heat, and flies. The unit’s first casualties on 29 July, Pte Percy Samuel Hindle and Pte William Daniel McCann, both in C Company, brought home the reality of war. Enemy shelling – artillery and mortars – combined with small arms fire and snipers to take their toll, even back of the line. The deaths of Pte James Bannatyne and three others on 2 August at Bourguébus provided stern reminders of the potency of enemy fire regardless of where you were. The Argylls’ first offensive action at Tilley-La-Campagne on 5 August resulted in heavy casualties, including Pte Joe Carlton, Pte Bill Wingate, and ACpl Coningsby Gooderham.

In the first week of action, B and C Companies had the most casualties; D Company had some and Support Company had a few [see Pte Lyall Wotton]. A Company’s first recruit to the Argylls’ “shadowy company” of the dead came on 8 August. That day the battalion was in Vaucelles, France. The war diarist noted:

The Battalion spent the day in Vaucelles, a large suburb of Caen. Bath parades were held, and beer distributed. This was in no sense a rest period: the troops were out of the line for a few hours only, and during that time they were confined to a small area…

The reason for the short withdrawal … soon became obvious. The First Canadian Army … was about to make the first of its break-throughs south of Caen towards Falaise [the second phase of Operation TOTALIZE]. The strategic moment … had arrived: on the right flank the American First Army had broken through in the Cherbourg Peninsula and was beginning its wide encircling movement; immediately to our right the British Second Army was attacking heavily and was drawing to its front some of the Elite S.S. Panzer Divisions. To the Canadian Army was given the all-important task of smashing the Caen hinge and thereby destroying the last vestiges of a stable German Front.

At 2300 hours the Artillery opened up with a tremendous barrage, and at the same time wave after wave of heavy R.A.F. Bombers, about 800, came over to spread a carpet of destruction … It was a perfect night for the raid – clear and bright.

Bill Jones died that night and 21 Argylls were wounded. CSM George Mitchell private diary entry for the day was a combination of upbeat and awestruck:

Back at Caen – comparatively quiet. Good meal – shower – shave etc – like new man.

Big push starts – Panorama of Vehicles, most amazing thing in history to date – terrifying. Every conceivable type of vehicle in Push – ground blasted by Air Force.

LCpl Harry Ruch was in 7 Platoon, A Company, and knew Bill Jones well. Ruch’s diary provides a vivid impression of the day.

“one of the most impressive sights I have ever seen”

Last night under cover of a Thousand Bomber raid we moved up behind the 2nd … Division. The aim was for the 2nd Div to smash a hole in Jerry’s line and we, the 4th … to exploit it with Armour. The Thousand Bomber raid was one of the most impressive sights I have ever seen. Ack-Ack bursting in the air; planes catching fire and blowing up; the noise and flash of 3,000 tons of heavy bombs landing on Jerry’s line. I wonder how he felt. I am glad we are on this side.

“we were on our way whether it be Heaven, Hell or Falaise”

About 0900 hrs we started, 600 tanks strong with carriers, truck etc. loaded with about 3,000 of us Poor Bloody Infantry. The moment had arrived and so we were on our way whether it be Heaven, Hell or Falaise. Jerry was not exactly completely knocked out and shelled us and we had a few uncomfortable moments. Advanced about five miles through the Essex Scottish of the 2nd Div. when we run into opposition. It was decided to call in the heavy bombers again so our section took cover in a large bomb crater while 500 large American Fortresses pounded Jerry about 1-3/4 miles ahead of us.

“After a sight like that one wonders how a man can live through it”

What a sight. The day was bright and clear and we could plainly see wave after wave of bombers overhead. They opened their bomb-bays right over our head and then we could hear the bombs starting to fall. The whistle of the bombs became louder and louder and then we could see them land on Jerry in front of us. After a sight like that one wonders how a man can live through it.

“One man wounded. One man killed. Bill Jones was killed.”

After the bombing we advanced about two miles and line up in front of a town called Cyntheaux [Cintheaux] in preparation for the attack. At the signal we started across the wheat field towards the town. While going through this field we captured two Jerries that tried to say they were “Canadians” but we heard that story before and sent them back to B.H.Q. It is rather a funny feeling going in on the attack. One don’t know what to expect. Your own shells whistling over your head, Jerry’s landing in front, amongst and behind you. Everything seems confused. We took the town alright and captured or killed about 300 Jerries most of them still dazed from the bombing. We were rather fortunate in regard to casualties. One man wounded. One man killed. Bill Jones was killed. We dug in and prepared for the counterattack that did not come.

“killed by the effects of blowing up that gun, a fellow by the name of Jones”

Some 40 years later, Ruch recalled what happened:

…It was our first taste of meeting the Germans face-to-face, even if they did surrender. They blew up an 88 gun and our first man in our company was killed by the effects of blowing up that gun, a fellow by the name of Jones. It felt pretty grim … Jones [had been] in the bed next to me almost all the way through Jamaica…

“… I always remember their bodies”

Jim Doyle of the Scout Platoon remembered “Billy Jones and Tommy Page” [LSgt Page] were early casualties … I always remember their bodies … in a ditch, on their back … flies circling around their mouths. And it’s a thing that just sort of shakes me every so often.”

“lasted only 16 minutes”

Death on the battlefield has many faces. Maj Bob Paterson wrote about this action in his history of the 10th Infantry Brigade:

It was a small scale action and lasted only 16 minutes from 6 o’clock to 6:16 in the afternoon, finishing with the capture of the objective, fifty odd prisoners, 15 enemy vehicles and 3 of the formidable 88 millimeter anti-tank guns.

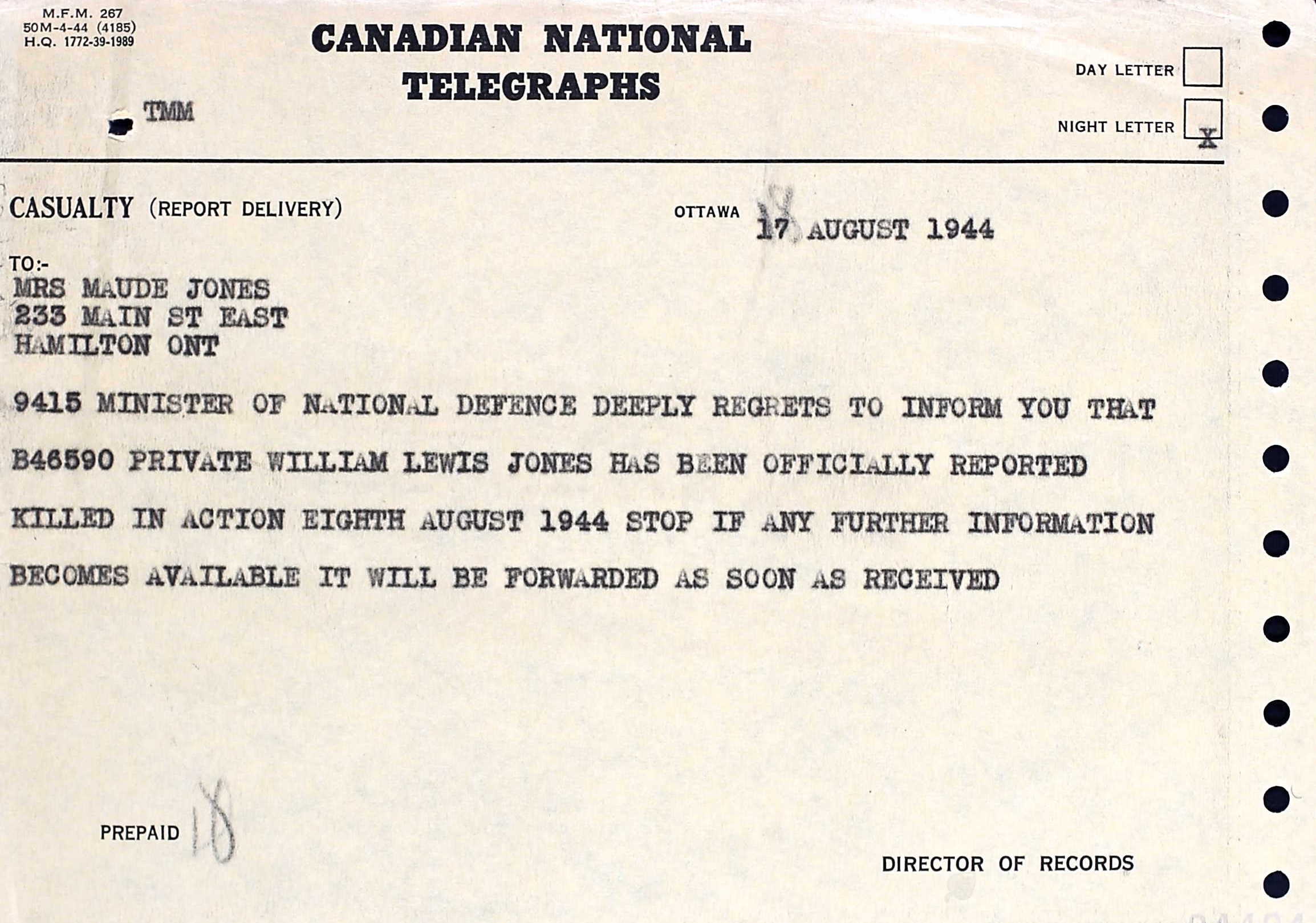

Paterson credited the South Alberta Regiment (SAR) with “valuable support … losing one tank but knocking out one 88. In this briefest of actions, either he Germans blew up their gun or the SAR tank did. Whatever the case, the shrapnel from the blast killed Bill Jones, A Company’s first death – “It felt pretty grim.” Lt Norm Donaldson, a platoon commander in A Company, reported Jones “Dead believed killed.” HCapt Charlie Maclean buried Pte Jones on 9 August at the northeast corner of the “Cross Roads” at Bretteville. There was a small burial party, a brief service, and a Regimental piper (probably one of the ones attached to A Company as a stretcher-bearer) playing the wartime Regimental lament, “Flowers of the Forest.” Like most Argylls, he left little by way of personal effects: a packet of photographs, and “A S H Cap Badge” and “Glengarry,” and “Imperial A S H Cap Badge,” a large photograph, a key, and a small photo case “W/Picture.” The life-shattering telegram announcing his death was sent on 17 August 1944. On the next day, 9 August, A Company lost another, LSgt Tommy Page.

When Pte Jones was reburied in Bretteville Canadian War Cemetery in 1947, his wife was notified; she was still living with his parents. Families could choose an inscription for the gravestone. The Jones family selected:

GOD REST HIS PRECIOUS YOUNG SOUL

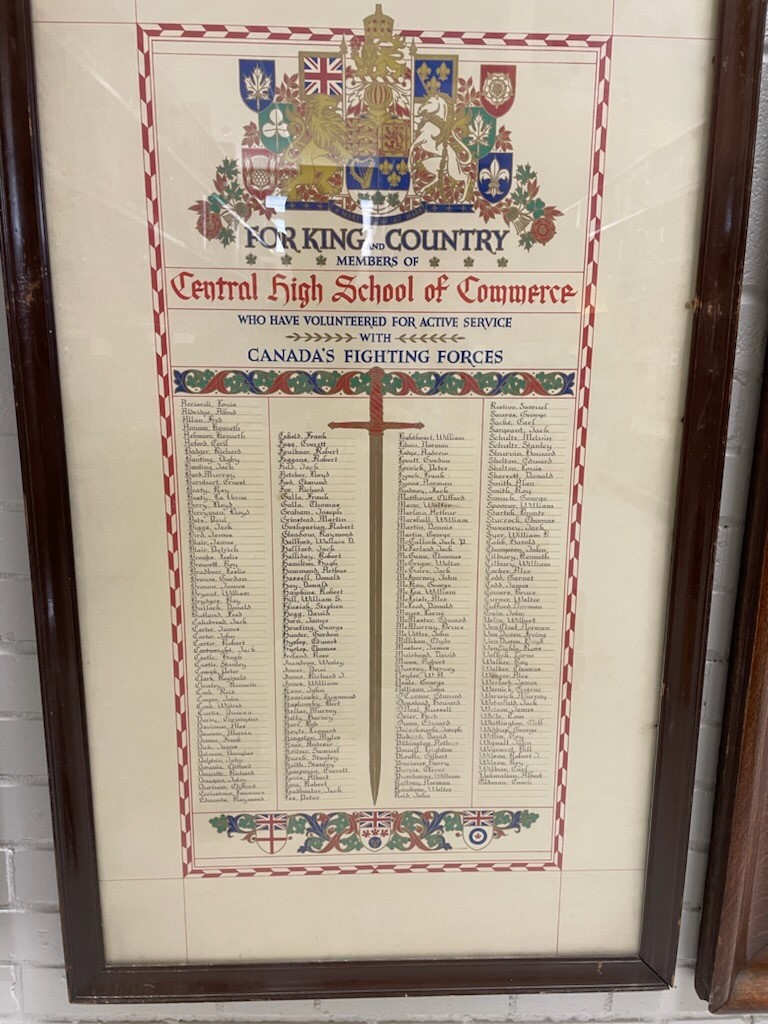

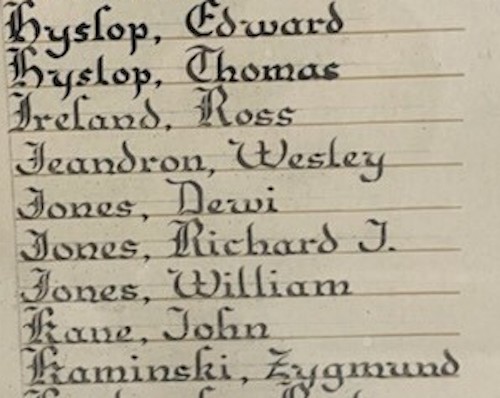

What happened to Maud Jones after 1947 is a mystery. Pte Jones is listed on his high schools Honour Roll (now in the school board’s archives).

“broken melodie of love + life”

Perhaps, Bill Jones’s Service Book jotting provides his epitaph:

Song of Songs

” of memory

+ broken melodie

of love + life

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Note: Pte Jones’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy for the Field of Remembrance.

Pte and Mrs. William Jones, Hamilton Spectator, June 1943.

Pte William Jones and his brother, Hamilton Spectator, April 1943.

Cintheaux, Normany, August 1944.

German 88mm AAgun.

Above and below: For King and Country: The names of Pte William Lewis Jones and his brother, Richard, are inscribed on the roll of honour, Central High School of Commerce, Hamilton.

Gravemarker of Pte William Lewis Jones in Hamilton.

Soldier’s cross of Pte W.L. Jones, Jones family plot, Hamilton.