Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

I have known about Jock Rennie’s life for a long time. In my first visit to the NCOs’ and Sergeants’ Mess in 1980, RSM Richard Seager, CD, introduced me – almost immediately, if I recall rightly – to the pictures of ASgt Rennie, GC, and Sgt Aubrey Cosens, VC. Their images have long had a hallowed spot in that mess; they epitomize military heroism in and out of battle at the highest levels. The Victoria Cross is the highest award for valour and the George Cross immediately follows it in precedence.

During the initial stages of the Black yesterdays project, I learned more about Rennie from 1st Battalion veterans. The Historical Committee, which I co-chaired with BGen Doug Fearman, included a large number of veterans, such as Colin Wallis and J.N. “Mac” MacKenzie. The committee applied, as one of its early initiatives, to the Ontario Heritage Foundation (OHF) for an OHF plaque to Rennie. The OHF’s board approved and the plaque was erected in the early 1990s. Rennie and his brother, George, were original Argylls enlisting in 1940. They were remembered well by the veterans and their names appear frequently in the Albainn, the veterans’ newsletter.

CWO (retired) Norm Wills, CD, often spoke of Rennie and the accident that took his life. The Argyll contingent that represented the Regiment at the funeral of our late Colonel-in-Chief visited the Argyll graves at Brookwood and requested an Argyll Poppy biography for him; CWO Wills had already arranged for an Argyll Poppy to be placed in the Field of Remembrance.

In 2015, the Rennie family graciously donated the George Cross to the Argyll Regimental Foundation and it now has a cherished place in the NCOs’ and Sergeants’ Mess.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

ASgt John “Jock” Rennie GC (1919–43) (B 45960) – AK 29 October 1943

The Rennie family has its roots in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is a large area in the northeast of Scotland whose staples were farming, forestry, and fishing. John Rennie (1852–1939) was an agricultural labourer who lived in Oldmeldrum, a small village north of the city of Aberdeen. George Rennie (1888–1974) was born there and lived there with his siblings. He married Agnes Jane Gordon (1894-1945) at “Insch, Scotland” (according to Agnes, a village northwest of Aberdeen), on 22 June 1912. Their daughter, Agnes Jeanne Rennie, was born in Inverugie, yet another tiny village in Aberdeenshire, on 1 November 1913 (she died in 1983).

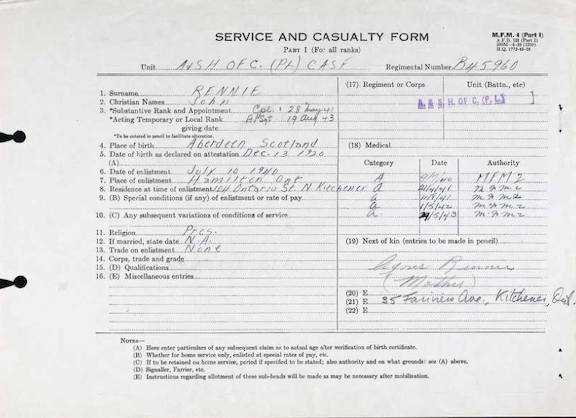

The historical record often presents wayfarers on the paths of the past with difficulties. John Rennie’s birth year is but one example. His attestation paper of 10 July 1940 gives 1920 as his date of birth. His occupational history form of 31 March 1941 makes it 1919. In his estate papers, filled out by his mother, she gives 1919. Unable to find a birth or baptismal record, I have settled on 1919.

Outward emigration is a dominant motif of Scottish history from the mid-18th century and Canada was a pre-eminent destination. Between 1919 and 1930, over 200,000 Scots immigrated to Canada. George and Agnes Rennie and their children were part of that group. In the aftermath of the First World War, the British Parliament passed the Empire Settlement Act, 1922. Its purpose was the resettlement of agricultural labourers, domestic servants, and juveniles throughout the British Empire. For its part, the Canadian government hoped to attract immigrants and especially ones from Great Britain (as a means of ensuring Canada’s assumed “Britishness”). Pte George William Wingate immigrated to Canada in 1925 at the age of 14.

“Empire Settlement office”

The Rennie family (George and Agnes, and their four children) sailed to Canada on 28 May 1924 on the SS Montlaurier, a passenger ship in the Canada Pacific Steamship Line. George Rennie’s declaration gives his occupation as “Farm Worker” and his intended occupation as the “same.” He was a Presbyterian and “Scotch.” He intended to settle permanently in Canada and had never lived there before. He had £10 in his possession (worth approximately $1,135.00 in Canadian dollars in 2022). He could read and his passage was paid by “Self + Empire Settlement office.” The family’s destination was “Mr H.S. MacDonell, Director of Colonization, Toronto, Ont.” There were no health or legal issues. The Canadian Immigration Branch admitted the family on 14 June 1924. According to a Kitchener newspaper report of 1 November 1943, the Rennie family moved there from Kingston. The family is not listed in the Kitchener city directories for the 1920s. The Kingston directories after 1923 are not available online. In Kitchener, George Rennie Sr worked as a landscape gardener.

John Rennie enlisted in Hamilton on 10 July 1940; the battalion had mobilized on 21 June. His brother George Rennie enlisted shortly after. John’s regimental number is B 45960; George’s is B 46080. He left school at “14” having reached “Sr. 4 Public School.” At the time, he had been employed by the “Canada Skate” Company in Kitchener as a “Press Worker” for three years. The company promised him employment again after his discharge and Rennie wished to return. In the city directory of 1938, the company is listed as “Canada Skate Mfg. Co. Ltd” at 348 Victoria Street. His occupation form noted that he was born on a farm in Scotland that practised “mixed” farming. He had no desire to be a farmer after the war.

Rennie was single, Presbyterian, and lived at 104 Ontario Street North with his parents and two siblings; the family moved a few months later to 35 Fairview Avenue in Kitchener, a modest two-storey brick home on a small lot. Drummer Jim Patterson of the Pipes and Drums (see Pte Richard McDonald) witnessed Rennie’s signature. Rennie was 5’, 7” and weighed 138 lbs. He had a “Dark” complexion, “Hazel” eyes, “Black” hair, and “Good” development. He had 20/20 vision in both eyes and good hearing, and reported no childhood diseases. Most personnel files of Argylls who enlisted early in the war contain one or two forms filled out by Personnel Board selection officers. They almost always contain a range of useful information about the soldier, his background, and his service record. There are no such forms in John Rennie’s file.

Pte Rennie was with the battalion in Niagara Camp on 28 August and was promoted ACpl at Allanburg Barracks on 18 November 1940. His rank was confirmed in Nanaimo, B.C., on 28 May 1941. He was attached to the Canadian Small Arms Training Centre there from 11 July to 31 July. The battalion returned from the west coast in mid-August to prepare for its move to its new home in Jamaica. There, the Argylls settled into a new life as guards at the internment facility at Up Park Camp and also handled ship inspections. Rennie contracted gonorrhoea there and was hospitalized on 22 November and then “Discharged to unit under surveillance” on 3 December. He was granted furlough from 20 to 31 March 1943 and again from 1 to 3 April 1943. Rennie’s military career was almost faultless except for one slight blot. He was AWOL from 0630 hours on 16 May 1943 until 2330 hours the same day. For this slight indiscretion, he was reprimanded and lost four days’ pay. Upon the unit’s return to Canada in May 1943, Cpl Rennie had “disembarkation furlough with subsistence allowance” from 1 June to 10 June; presumably, he returned to Kitchener and his family. Agnes Rennie, in a newspaper article of 26 May 1944, said that John and George “always arranged to have their leaves together.”

The Argylls went overseas in July 1943. They were inspected at Frimley on 17 August by an “inspection team.” After the war, Maj Hugh Maclean deemed it “the most rigorous to which the unit was ever to be subjected.” Five days later, they received word that the battalion had “passed” and would join the 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade of the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division. Rennie was appointed ASgt on 19 August.

Between 22 December 1941 and 1 January 1944, five Argylls died because of accidents. Lt John Osborne, son of the Honorary Lieutenant Colonel, Colin C. Osborne, was accidentally shot and killed in Chippewa Barrack while playing quick draw with another officer; one revolver was loaded. On 1 January 1941, Pte Edward J. Robillard “died as a result of injuries received when he was struck by an automobile, all soldiers were warned to face oncoming traffic, when walking along the highway.” Then, on 24 April 1941, Pte Clifford L. Brant drowned in the Welland River. He was AWOL and, after a night of drinking with another Argyll, he tried to swim the river to elude the guard sent to return him. Maj Walter Hobart Bruce died on 6 November 1941 as a result of a motorcycle crash when returning to CFB Borden.

“he was faced with one of those decisions which shows a man’s true colours. “Jock” did not fail!

In the months after Frimley, the unit underwent intensive training (see Pte William Lewis Jones). As an ASgt, “Jock” (as he was called by Argylls of all ranks) Rennie played a key role in platoon-level training for D Company, his rifle company. Range work with the small arms that were the tools of the infanteer’s trade played a central role. Jock Rennie died on the training ranges at Riddlesworth Camp on 29 October 1943; it was an accidental death different from those that preceded it.

War diarist Maj Art Hay wrote:

For the first time in over 2-1/2 years the shadow of tragedy fell across the Argylls. A tragedy no less sombre because of the added touch of heroism. Sergeant “Jock” Rennie – an efficient soldier and a real gentleman was killed to-day on active service. While instructing “D” Company, of which he was a member, in the art of hand grenade throwing, he was faced with one of those decisions which shows a man’s true colours. “Jock” did not fail! A poorly thrown grenade rolled back toward the pit from which it was thrown, endangering many lives. Shouting to the rest to take cover, Sergeant Rennie flung himself at the grenade in a desperate effort to throw it out of danger. When waist high in his hand the lethal weapon exploded. “Jock” was horribly mutilated and because of this we are thankful to say died almost instantly, but the lives of the others were saved. A fine soldier and comrade has been lost but a tradition found. A tradition of coolness and courage in time of stress. The men of this regiment will never forget.

Sergeant Rennie’s parents were notified via cable immediately and efforts made to get in touch with relatives in Scotland.

“Jock was our friend and … we felt pretty badly about it … a very decent, capable man”

Jock Rennie was a popular, well-regarded soldier among all ranks. Lt Bob Pogue, the Pioneer Officer, recalled:

… I was right behind the two people throwing, and Jock [Sgt Rennie], in the centre, [was] supervising … you don’t anticipate a guy having so little coordination that he can’t throw a grenade over an embankment … he was apparently so frightened that [the grenade] kind of bounced and rolled down [the embankment] … Jock went to pick it up with his left hand and fouled it because he was right-handed. I think I hollered, “Everybody get down!” But then I started to run … towards them. You just feel helpless. Then by the time he got it in his right hand, it blew up, and pieces hit this boy and I still have shrapnel in [the] arm.

… the guy that threw the grenade was just shipped out. What else can you do? You can’t blame a man for fear and lack of coordination … there’s no precautions that can be taken. I mean you have to simulate to a certain extent wartime conditions, and we can’t use dummy grenades. Eventually, you’ve got to get people used to the sound … but nobody ever anticipated this fellow’s coordination being so poor that he couldn’t throw it over…. Also, the army was in some ways a little to blame because they insisted on you throwing a grenade like a cricket ball, instead of pitching it, as a Canadian would.

… Jock was our friend and, by Jesus, we felt pretty badly about it … he was a very decent, capable man who you could envisage being your friend in civilian life. He was that sort of man…

“My God, what did I do?”

Sgt Robert E. “Bun” Tapping, D Company, “went over and picked Jock up off his helmet and oh, his face – everything – was gone. But all he said was, “My God, what did I do?” That’s all he said and did….” Sgt Rudy Horwood of the Anti-Tank Platoon offered a perspective some 40 years after the war:

… soldiers expect accidents and expect some people are going to be killed, and some people are going to be badly wounded, some people are going to be crippled, and some people are going to have mental breakdowns. And so I think we were prepared for violence and death … I don’t really think there was any great wave of shock [following Rennie’s death]…

HCapt Charlie Maclean, the Argylls’ padre, joined the unit on 10 September 1943. By war’s end, he commanded what Capt Claude Bissell called “the shadowy company of the dead.” ASgt Jock Rennie was the first to join the good Padre’s company. Charlie Maclean’s services were brief, respectful, and dignified, and a piper always played the Argylls’ wartime lament, “Flowers of the Forest.” Rennie was the first of three Argylls buried in Brookfield Military Cemetery. LCpl Fred Woodward and Pte Tom Nangle were the others.

“the Grim Reaper”

The last pre-combat death occurred at Uckfield on 1 January 1944. Maj Hay wrote in the unit’s war diary:

The New Year and the Grim Reaper visited the battalion almost hand in hand for Death, that had taken a holiday in Jamaica, struck for the second time during our sojourn in England. B45656, Pte. Broker, A., an Argyll of long standing and popular with everyone in the regiment, was run over and instantly killed by a bus at 0630 hours this morning in the vicinity of Lewes, Sussex.

By a strange co-incidence, Pte. Broker had previously been a sergeant in “D” Company and a close friend of Sergeant Jock Rennie whose tragic death at Riddlesworth had come as such a shock to the battalion.

The battalion, however, carried on as it would later do in battle; there is no choice. The war diarist’s last note was:

“Officers and Sergeants traded social amenities this New Year’s Day with the Sergeants playing host to the Officers in the morning and the Officers returning the courtesy in the afternoon.”

“The second grenade fell short about 8 feet ahead of the thrower”

Rennie’s death necessitated an investigation. On 30 October, the battalion’s new commanding officer, LCol J. David “Dave” Stewart ordered a Court of Inquiry. Capt R.A. “Flan” Paterson, 2ic of C Company, was its president. Lt Al “Kelpie” Rathbone of the Mortar Platoon and Lt D.G. Plant were its members.

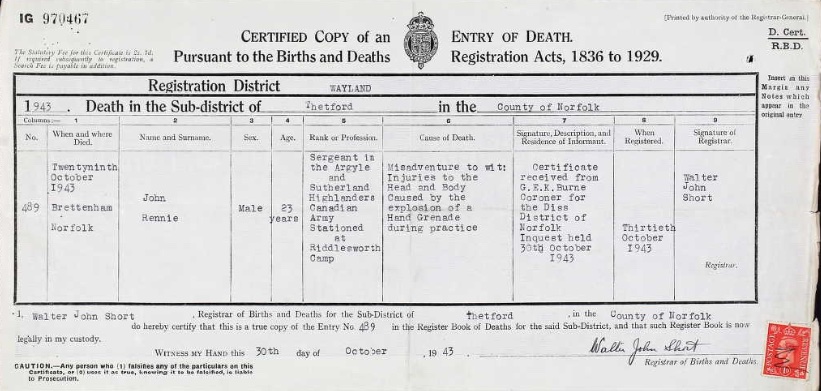

The court found that Rennie had “Shrapnel wounds (grenade) of facr [face], rt eye and skull, rt arm and chest in region of heart, and other abrasions – fatal.” The accident occurred at “approx 1440 hrs” on the 29th. The soldiers were throwing “36 grenades. Pte. [P.]Pillipow had thrown one grenade successfully was warned that he was a little slow. The second grenade fell short about 8 feet ahead of the thrower. Sgt. Rennie bent forward to pick up the grenade to throw it and the grenade exploded.” Rennie died “from head and chest injuries.” Pillipow had a “shrapnel wound of the right thigh” and Lt Pogue sustained “a wound in the left arm.”

The court concluded that Rennie’s death was “accidental and was caused by Pte. Pillipow’s unintentional failure to throw the grenade far enough to clear the protective embankment and also Sgt Rennie’s difficulty in picking up a rolling grenade.” Secondly, it ruled that “all possible safety precautions were taken during the grenade practice.” Higher formations at every level affirmed its conclusions.

“gruesome affairs…”

LCpl Harold E. “High Explosive” Carter of the Anti-Tank Platoon wrote home about the two accidental deaths on 11 January 1944.

… The Grim Reaper is certainly having a field day. We had a death on New Year’s morning early when a driver stepped out of his lorry and was struck by a bus. He looked like hamburg steak. And the sad part was he was very well liked. I don’t know whether I told you about the accident we had in October. A sergeant [Jock Rennie], nice guy too[,] was directing a group in throwing hand grenades from a pit when one nervous fellow failed to clear the pit so that the grenade fell back into the pit. Well to shorten the story the sergeant pushed the others aside, grabbed the grenade to his stomach and it – well you can guess what happened. But enough of these gruesome affairs…

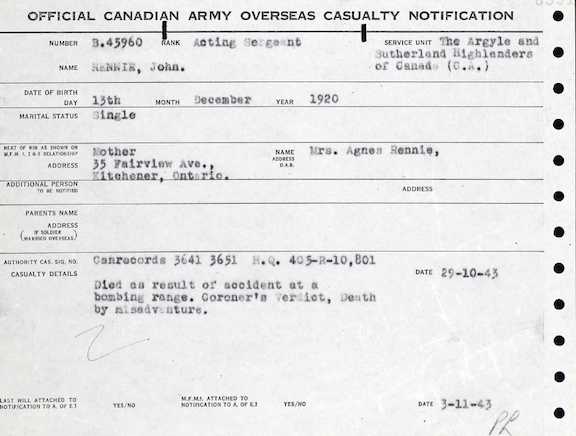

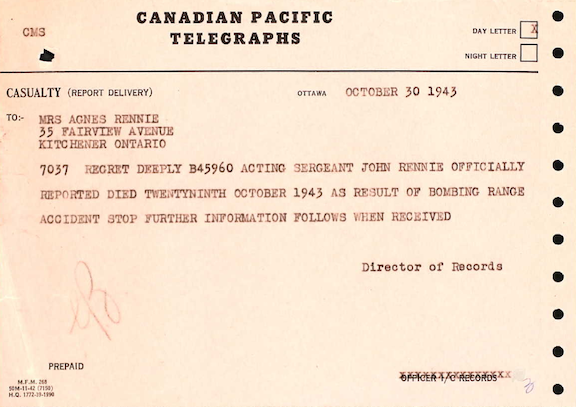

Rennie’s mother, Agnes, listed on his military forms as his next-of-kin received the dreaded telegram on 30 October advising her that her son had died “As result of bombing range accident.” The Director of Records wrote to her on 26 January 1944 “In keeping with the policy of the Canadian Army in informing the next-of-kin of the details of all casualty cases.” In doing so, Col C.L. Laurin offered an “extract from the evidence given at a Coroner’s Court in England.”

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friend”

Sgt Rennie “was in charge of men undergoing hand grenade practice at Brettenham about 1400 hours using battle grenades.” He “gave the order for the men to throw the grenade over a wall about four feet high.” The first throw was successful. During the second run-through, one soldier’s “grenade struck the top of the bank and … rolled back towards him…. Sgt. Rennie sprang ahead shouldering the comrade out of the way to get the grenade. He tried to pick it up to throw it over the bank but it exploded as he was picking it up. He was severely injured. The evidence is that he died from severe injuries of the head and chest.”

Laurin concluded his letter with an expression of “my sincere and heartfelt sympathy for the irreparable loss you have suffered…. Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friend.”

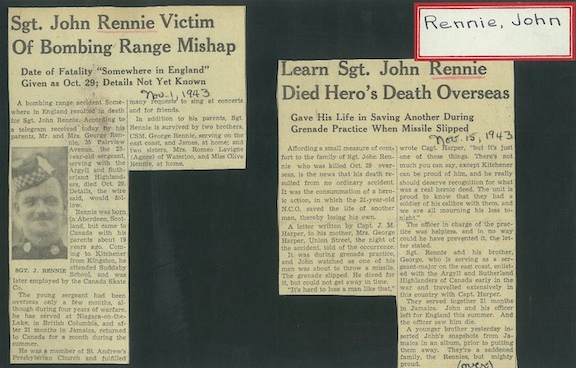

“Died Hero’s Death Overseas”

By 1 November 1943, newspapers in Kitchener reported Rennie’s death. They mentioned his attendance at Suddaby Public School and his activity as a member of the choir at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church. John Rennie loved music “and fulfilled many requests to sing at concerts and for friends.” In May 1944, another newspaper report noted that he “was a good singer.” On 15 November, the tenor of the articles changed and the headline for the article read, “Died Hero’s Death Overseas.” The shift resulted, apparently, from a letter home written by Capt Jack M. Harper, another Kitchener lad and Argyll, and 2ic of A Company. The newspaper noted:

“Affording a small measure of comfort to the family … is the news that his death resulted from no ordinary accident. It was the consummation of a heroic action, in which the 21-year-old N.C.O. saved the life of another man, thereby losing his own.”

Newspaper clippings from 1 and 15 Nov 1943 (Kitchener Public Library).

“a soldier of his calibre”

Capt Harper wrote a letter to his mother on the evening of the 29th after Rennie’s death.

“It’s hard to lose a man like that but it’s just one of those things. There’s not much you can say, except Kitchener can be proud of him, and he really should deserve recognition for what was a real heroic deed. The unit is proud to know that they had a soldier of his calibre with them, and we are all mourning his loss tonight.”

The report concluded: “That are a saddened family, the Rennies, but mighty proud.”

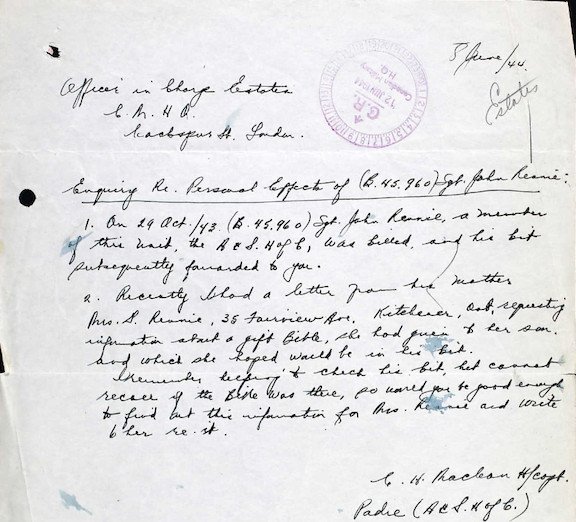

After a soldier’s death, the army handled estate-related matters such as pay owing, the benefactors of his estate, and personal effects in his possession. The list of Rennie’s personal effects consists mainly of military clothing. There is also a fountain pen, 4 Shick injector magazines, a letter case, a map of Canada, a wallet, a New Testament, a protractor, a pipe, and an harmonica. There were, in his parents’ view, problems with the list. George Rennie wrote on 27 May 1944 that “there are a few things missing” and asked the army to check. The items were a military brush set, wallet, cigarette light, razor, speed skates, camera, ring and “colt automatic revolver.” Padre H/Capt Charlie Maclean wrote the “Officer in Charge Estates” that he “Recently had a letter from his [Rennie’s] mother … requesting information about a gift bible, she had given to her son and which she hoped would be in his kit.” For his part, Maclean added, “I remember helping to check his kit, but cannot recall if the Bible was there, so would you be good enough to find out this information … and write to her re it.” There is no indication whether their concerns were ever resolved.

Letter about John Rennie’s Bible from HCapt Charlie Maclean to Officer in Charge Estates, 8 June 1944.

“… without the slightest hesitation dashed forward …”

Jock Rennie’s tale had one last chapter. His heroism on that day, noted immediately by the war diarist, made a lasting impression. Central to it is one incontrovertible fact:

“Despite the fact that he had the time and opportunity to escape from danger A/Sgt Rennie without the slightest hesitation dashed forward interposing himself between the grenade and his comrades and attempted to pick up the rolling grenade and throw it clear.”

“his sacrifice”

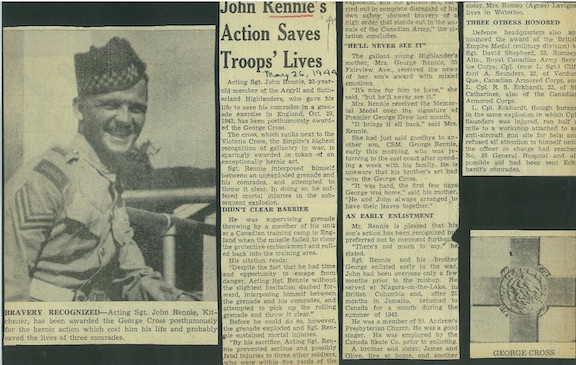

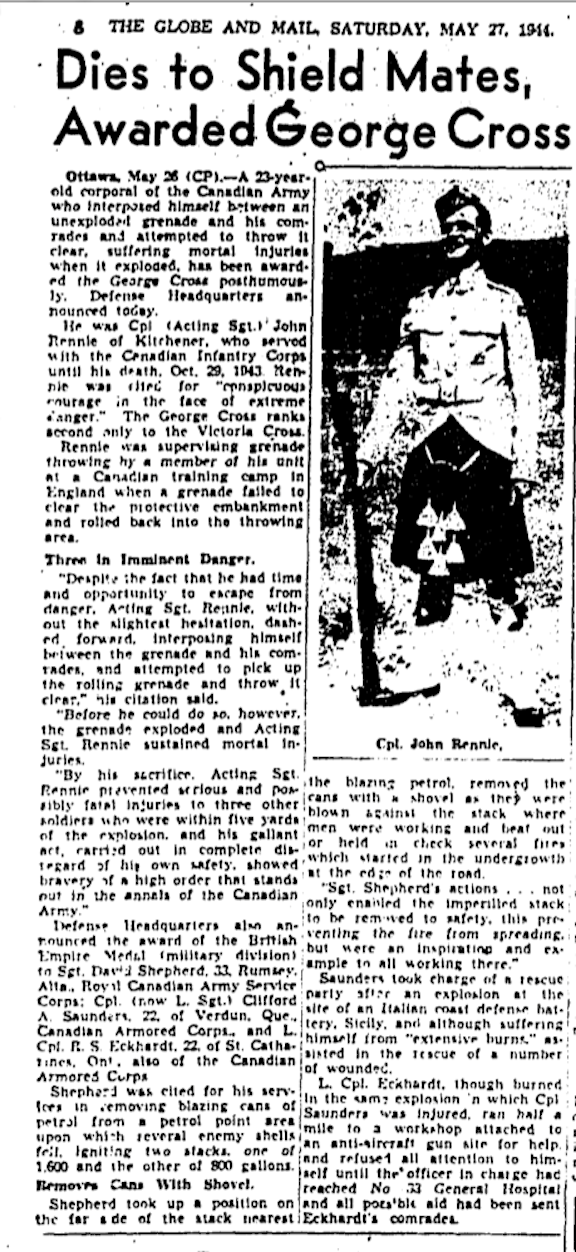

Rennie’s instantaneous response – “his sacrifice” – “prevented serious and possibly fatal injuries to three other soldiers who were with 5 yards of the explosion and his gallant act carried out in complete disregard of his own safety showed bravery of a high order that stands out in the annals of the Canadian Army.” He was awarded the George Cross posthumously; the award was gazetted on 26 and 27 May 1944. It “was awarded for an act of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger.” Intended for civilians for the most part, an “award in the military services was confined to actions for which purely military honours were not normally granted and actions not in the face of the enemy.” Ten Canadians received the George Cross during the Second World War. Eight were military; of those only three were army. ASgt John “Jock” Rennie was in rare company.

“it’s nice for him to have, but he’ll never see it. It brings it all back.”

Kitchener newspapers reported the award on 26 May 1944 and interviewed Agnes and George Rennie. They received the news “with mixed emotions.” For John’s mother, “it’s nice for him to have, but he’ll never see it. It brings it all back.” John’s older brother, George, had been home on a visit and left to return to his unit on the 26th. “It was hard,” Agnes said, “the first few days George was home. He and John always arranged to have their leaves together.” As for John’s father, he “preferred not to comment.” “There’s not”, he said, “much to say.” Agnes Rennie died in 1945.

Newspaper clipping from 26 May 1944 (Kitchener Public Library).

Globe and Mail, 27 May 1944.

“among the best that Canada can produce”

ASgt John Rennie has not been forgotten either by his own family or by his Regimental one. There are many references to him in the Albainn, the post-war newsletter of the 1st Battalion Veterans’ Association. His image and his medal hang in the Argylls NCOs’ and Sgts’ Mess. And his memory lingered in the private memories of Argyll veterans who knew him well. In the 1960s, Capt Bob Pogue “suffered a period of melancholia brought about by nagging remembrance of the deaths of men I had admired and respected … my own comrades – Jock Rennie, Al Dalpé, Norm Donaldson, Lloyd Johnston, Mac Smith – and so on.”

“The thought would constantly come back in my mind – why these men? Emotionally I will always feel that these soldiers, from private to colonel, were among the best that Canada can produce.”

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him

LCol Glenn De Caire, LCol Carlo Tittarelli, CD, CWO Mark Brewster, CD, Pipe Major Scott Balinson, CD, and Cpl Eric J. Korten visited Brookwood Military Cemetery while representing the Regiment at the funeral of our Late Colonel-in-Chief, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, in September 2022. They visited the graves of Argylls buried there: ASgt John Rennie, LCpl Fred Woodward, and Pte Tom Nangle. The latter two have Argyll Poppy biographies. The group donated $500 to the Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) in ASgt Rennie’s memory.

Note: CWO Norm Wills and Lisa Wills purchased a poppy in ASgt Rennie’s honour. It will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The ARF commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Cpl John “Jock” Rennie.

Cpl John Rennie in Jamaica.

Oldmeldrum, Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

35 Fairview Avenue (centre home) in Kitchener, Ontario, today.

St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Kitchener.

Suddaby School, Kitchener.

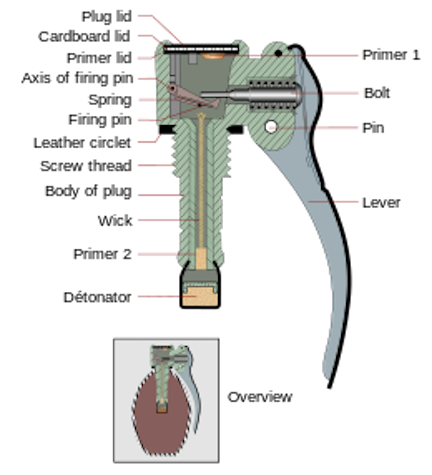

No. 36 grenade.

No. 36 grenade workings.

Military-issue razor set: 1942–43 Shick Injector Type E.

George Cross.

ASgt Rennie’s grave marker in Brookwood Military Cemetery.

Grave of ASgt Rennie’s parents, George and Agnes.