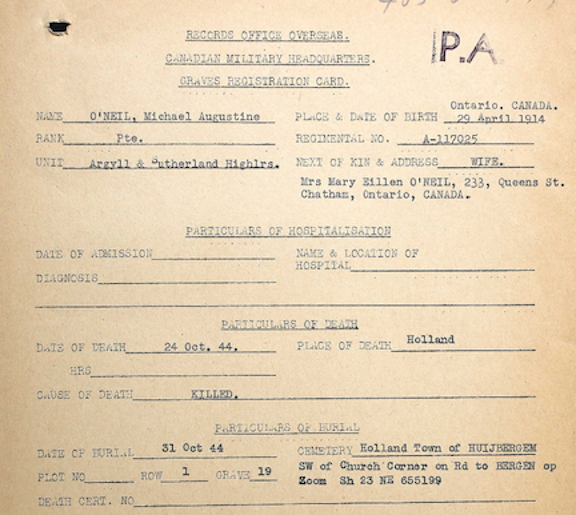

Pte Michael Augustine O’Neil (1914–44) (A 117025)

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

I knew of Pte O’Neil slightly, one of the C Company soldiers killed during the grim fighting on 24 October. Most of the Argylls who died that fateful day were from C (at least 7 of 13; 2 from A; 2 from B; and 1 unidentified). Last year, I wrote about one of the B Company casualties, Pte Bill Du Trizac.

In September 2021, I received a call from Daniel Eichenberg, a grandson of Pte Mike O’Neil. Daniel sought information on his grandfather’s service with the Argylls. We exchanged emails and I asked whether the family had images, letters, or artifacts. Little did I know what Clan O’Neil had in store for me? He put me in touch with his aunt, Mary Kay O’Neil-Lowy, and after a phone interview, we arranged to meet at her sister’s (Nan Eichenberg). I arrived there to be greeted by the clan – Pte O’Neil’s children Mary Kay, Mike, and Nan as well as Daniel. I interviewed them and Mike turned over to my temporary safekeeping a trove of letters, keepsakes, and images. I have come to know, like, and respect Pte O’Neil and Mary Eileen O’Neil. I offer the O’Neils my thanks to for their assistance and their warm introduction to their parents. It is quite a family.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

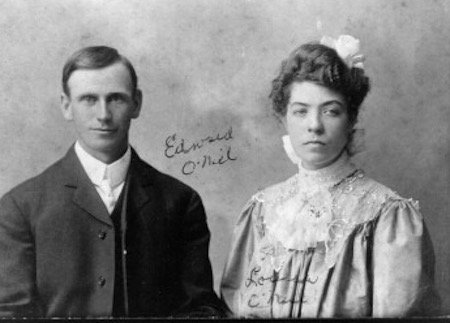

The story of Canada since European contact is, in large measure, a tale of emigration. The O’Neil family originated in Ireland and immigrated to Upper Canada (part of present-day Ontario) in the 1830s. Timothy O’Neil (1837–1920) was born in Toronto (both his father and mother were born in Ireland). By 1861 he was living in Dover Township, Kent County, and working as a labourer. Kent County was farming country, with a large amount of arable land suitable for grain and mixed farming. The O’Neils settled in Dover. He married there, acquired a farm, and raised a family. Timothy and his wife, Sarah “Sary” Kelly (1846–80), had several children, including Edward Aloysius O’Neil (1875–1927). Edward and his wife, Mary Louise Faubert (b. 1886), had four daughters and four sons. The entry for the 1921 census lists Edward as a farmer who owned his own acreage and lived in a wood house with eight rooms. The family was Roman Catholic, everyone could read and write, and they spoke English only.

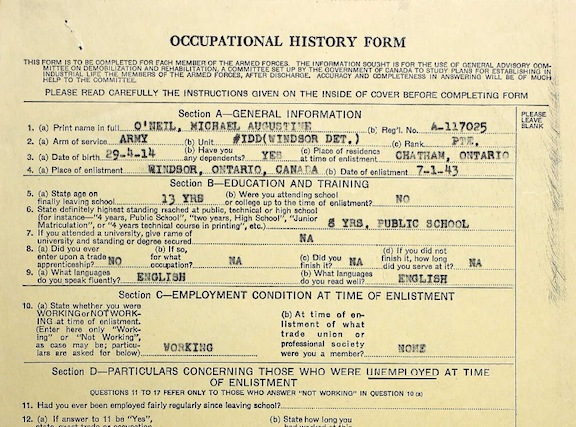

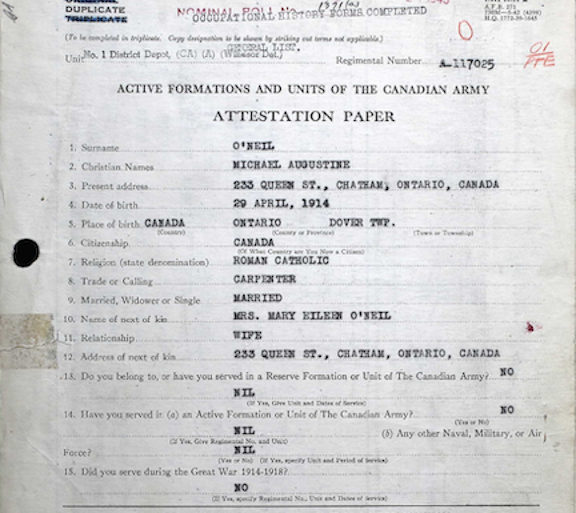

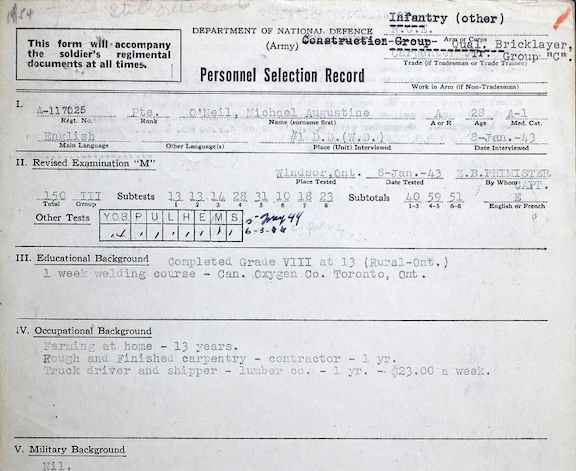

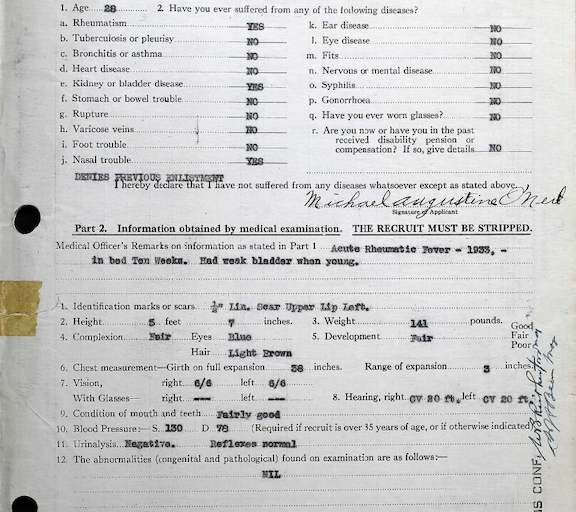

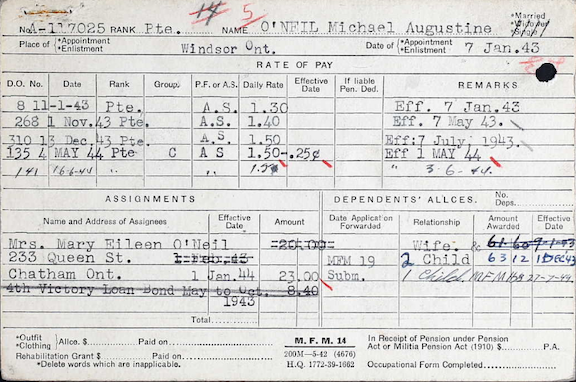

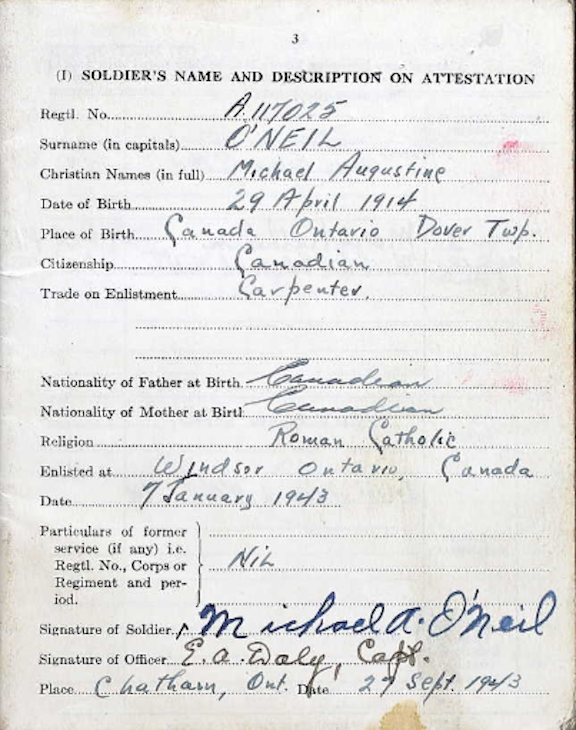

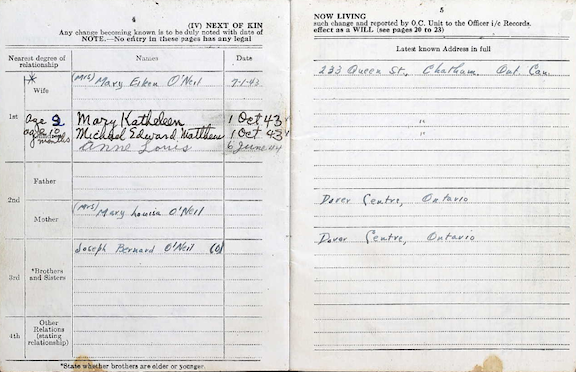

Michael Augustine O’Neil was born on 29 April 1914 in Dover Township, the son of Edward Aloysius O’Neil and Mary Louisa Faubert. His parents had married on 5 June 1905 at Pain Court. A married carpenter living at 233 Queen Street, Chatham, Ontario, Mike O’Neil enlisted on 7 January 1943 in Windsor, Ontario. During his medical examination, he answered affirmatively that he had “suffered” from rheumatism and kidney or bladder disease. He explained that he had “Acute Rheumatic Fever” in 1933 and had been “in bed Ten Weeks.” He had a “weak bladder when young.” He had a ½-inch scar “Upper Lip Left.” He was 5’, 7”, 141 lbs, with a fair complexion, blue eyes, and light brown hair. He was interviewed on the 8th by a personnel selection board (PSB) officer. He had completed grade 8 “at 13” at a “Rural-Ont” school in Dover Township; he left in 1927. He had taken a one-week welding course at the Canadian Oxygen Company in Toronto.

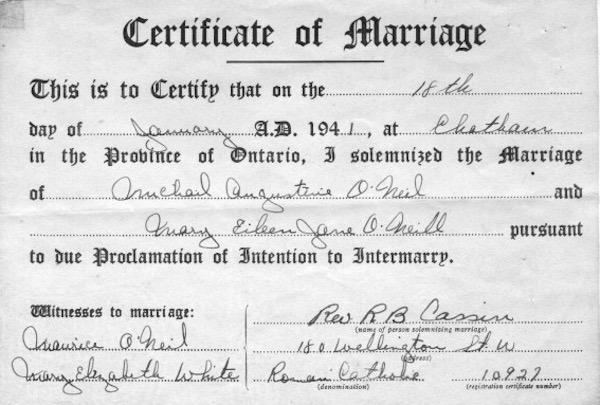

Mike O’Neil’s occupational history changed in the years prior to his enlistment. From approximately 1927 to 1940, he did “Farming at home.” He then worked for a contractor in 1941 doing “Rough and Finished carpentry,” and in 1942 he worked as a “Truck driver and shipper” for Beaver Lumber Company in Chatham, earning $23 weekly. He had no military background, considered his health “very good,” and enjoyed “Woodworking” as a hobby. He had “General sports interests,” liked skating, and played softball (“city league”). Although he considered himself “competent to operate a farm,” he wanted to return to Beaver Lumber after the war and hoped to be a carpenter. He married Mary Eileen O’Neill (her family had a second “l” in their name) at St Joseph’s Church, Chatham, on 18 January 1941.

“reliable, conscientious sort of man”

The personal history and general appraisal section of Pte O’Neil’s evaluation is unusually fulsome, possibly a reflection of the PSB officer’s inclinations or O’Neil’s presence or both:

Marital Status: Married in January, has one child and wife, is anticipating arrival of another. Wife living in home owned by man in Chatham Ont. Religion: Roman Catholic. Attends Church regularly. Belongs to Holy Name Society [a lay confraternity of Catholic men]. Habits: Temperate and moderate. Man appears to be happily married and enjoys usual forms of normal social activities and interests. No police record. Appears emotionally stable. Summary: States he has done considerable carpenter work over past 5 Years, both rough and finish; has worked on home remodelling, rockwool work etc. Would like duties as a carpenter. In working with contractor and private carpenters in Chatham man states he has worked 6 weeks at # 12 B.T.C. [basic training centre]. Presents good appearance, is alert and responsive. Appears to be reliable, conscientious sort of man.

There were two recommendations: “Suitable for Trades Testing as R.C.E. [Royal Canadian Engineers] carpenter” and “Infantry (other) Construction Group.”

“well satisfied with every thing” – “this is the Army Mrs Jones”

On 11 January 1943, #1 District Depot took him on strength; his son, Michael Edward Matthew O’Neil, was born two days before. Pte O’Neil assigned $20 monthly of his pay to his wife. Upon joining he received $1.30 daily (seven days a week), or approximately $40 monthly. On 13 January, Mike O’Neil wrote “My Darling Wife” from St Luke Barracks in Windsor. He was “at the army Barracks again well satisfied with every thing.” He started “my daily chore, of washing pots pans kettles from 7 a.m. till eleven and still plenty more to do.” After a trip to the dentist for a check up, he “reported immediately to the tool house and started carpenter work. I like it very well.” He told her that he “enjoyed the meals to day they have a good variety which one would not get tired off [sic] – if he does hes [sic] nuts.” He urged her not to worry and “hated to go again the other day and leave little Mary Kay and Aunt Alice but duty calls this is the Army Mrs Jones…” He signed off, “Your Loving Husband.”

“bath, read, sleep, eat, almost a King[’]s life”

Mike O’Neil’s letters are affectionate and loving. On the 16th January he wrote, “Hello my little lover how are you getting along? I do hope you are fine…” He had a weekend leave every three weeks and said he leaves “every night till twelve.” He planned to send $4 “at least … to keep aunt Alice and Mary Kay from going hungry especially M.I. and her appetite.” As for his son, Michael Edward Mathew O’Neil “should be proud of a long name like that but would get tired of signing it if he had to as many times as I have since coming here.” He complained that “buying thing[s] I really need … all help to run my small salary low.” As for the work, it was light and described the rest of a day: “bath, read, sleep, eat, almost a Kings [sic] life.” “We just get going good,” he noted wryly, “when along come some one to get you for teeth, finger prints other documents.” He was glad of the dental work because he had a “few cavities to fill … and they sure fix you up well.” On his last visit home, Mike’s close friend, Jerry Sands, “saw me off … I think he’d like to be in the Army too.” Mike observed “it[’]s funny how one contents themselves to it every one seems to. You never hear but very few do any kicking its not half bad. There are not many that I know but the boys in and around our [work] bay are very good guys, which helps a whole lot in the Army[.]” As he neared the end of the letter, it became a circle returning to Eileen. “Well honey bunch I wish I were near you so I could hug and hug and hug and hug you and to give you those kisses I forgot to give you last week. Darling you will never leave my thoughts as long as I live you are such a brave and comforting wife and I will never let you down sweetheart. You can have all my love a little at a time, war you know every thing rationed these days.” He urged her to “cash a cheque this time” if she needed money and hoped to send more with his next pay. He wondered “how big the hospital bill is dear and how we[’]ll make out with every thing[?] “I love you darling xxxx Mike.”

“we have to learn things a lot faster”

His letter of 10 February 1943 brought news of his training. “We started our marching Mon night. It didn’t last so very long – 4-5-6-7 time goes so fast when marching we have to learn things a lot faster taking our basic this way it will count they tell us now things we learn in one night and do right would ordinarily take a week. Mon night and Tues we did every thing but stand on our heads. Sargent [sic] told us just because we did that right not to let our heads get to[o] big …” On Wednesday “we get rifle drill + lecture th[e]n from there will be gas with our resperators [sic] to test them for leaks tear gas is used for that so if it leaks we[’]ll probly [sic] do a lot of crying other wise it wont be so bad.” He went to Detroit one night, bought two cartons of cigarettes, had lunch at the U.S.O., “had one dance,” and came back “with a bag of peanuts” and “jumped into bed.” In closing, “I can say you are a sweet little wife and I love you very much. Kiss the babies for me darling and say Hello to Aunt Alice … Your Loving Hubby Mike.”

“You need a good time too and not so much work”

On 23 February, Pte O’Neil penned a short note in anticipation of meeting Eileen at the train station in Walkerville (near the barracks) on Friday night. “We[’]ll get about a dozen ales and then takeover … You need a good time too and not so much work.” Two days he fretted that, although Friday was pay day “as far as I know … you had better bring at least five bucks with you in case we don’t.” He still had two dollars but planned on going to the United States to pick up a carton of cigarettes “and will likely be broke.” He hoped “every thing is turning out for the dance.”

“to bind together a love and a happy home for both you and me and our little family”

Windsor and Chatham were close, about 50 miles by train. The proximity allowed Mike and Eileen to see each other often. He wrote his “Dearest Wife” on 16 March:

Here I am writing another letter to the sweetest and kindest person in the whole world. One who leaves thoughts of kindness and great love to remember them by to bind together a love and a happy home for both you and me and our little family[.] It was so nice of you to come down to the train [S]unday night darling and I hated to leave you on the street alone … and when I become captain look out, I’ll buy you that new fur coat. It was mink you wanted wasn[’]t it darling[?] Well that would be all right anyway if you’d rather have muskrat – Muskrat it’ll be.”

“I think of you always darling”

There was more “marching + drilling,” “rifle drill,” and “map reading.” The latter proved difficult and O’Neil estimated “around 75 percent failed” – “I had better brighten up.” As always, pay was never enough and he anticipated “when I get the extra raise both for you and[d] me both.” He signed off with “Love to the babies mother and Aunt Alice.” On 23 March Mike thanked Eileen for “those home made cookies” of which only “three half cookies” survived the inquisitive postal service “feeling pressing and smelling to see what was in there.” As a result, most had been rendered “as fine as sawdust but I ate it anyway they sure were good.” He had received one of her letters and he “was glad to hear from you sweetheart I think of you always darling.” Training “is over now” and the soldiers quit work at 4 p.m. The “weather is so fine now it just makes you feel love sick and want to be near you always. I just think of all that moon going to wast[e] when we could be doing a little necking.” He related to her the recent stage show with singing, tap dancing, card tricks, and “also a fan dancer and could you imagine her with only a few feathers on behind the fan. We soldiers were so humiliated. Ha. Ha.” He offered up the hope that Mary Kay could “push Michael around in her little buggy then you could just lay down and rest.”

“in the army they don’t miss a thing”

Pte O’Neil wrote home on 6 April. “Gee it was swell to be home for a long week end sweetheart … I sure hated to come back because there is so dam much time wasted around here I sometimes get fed up.” He hoped to cross the border but someone had stolen his pass while he was away.… There has been several taken lately so they are giving us our identification cards right away soon.” On 7 April Pte O’Neil was chagrined to learn “our little baby has a bad cold.” Mike “just came of[ff] some more of our basic training. It is bren gun tonight getting ready to go out to the rangers for target practice. It will be two hrs one night Wed. every week for one month…” Forty soldiers, including him, had been picked for a “performance” later in the month “marching with rifles, tin hats, and skeleton Web equipment around and around and around then bugger off for home.” On 12 April Mike regaled Eileen with the plans for a softball team. For his part, “I hope to make team it will be such fun for the summer.” The extraction of a wisdom tooth – “boy was it a whopper” – was less so. The dentist “froze it and then took a pair of pliers about a foot long put both feet on my shoulders got another man behind him and yanked it out its been bleeding all day …” He urged Eileen to take care of her teeth, and was pleased “that will save me a little doe and they sure fix them well in the army they don’t miss a thing.”

On the 20th, Mike broke the news that special Easter leaves were unlikely “as a soldier is on duty 24 hrs a day always.” He vowed to try and make it home. As always, enlistees from 1943 or 1944 made their journey through a series of interviews conducted at each stage of their soldier’s progress through training. Pte O’Neil reported “nearly every one of the boys are getting reinterviewed as to what unit they are going to join. I haven[’]t been told to report yet am just keeping my fingers crossed and taking for granted that I’ll stay for baseball.” His letter of the 28th began with the usual opening – “Hello sweetheart how are you and the babies?” He had time for a “short letter before supper and ball practice” and a movie, Pacific Blackout, a 1941 espionage film, in the evening. He had decided to buy a $50 wartime savings bond, having “worked out a little scheme that might work.” He hoped she would like the plan. Mike told Eileen on the 30th that “our training isn’t as stiff as it was when I left in Jan really nothing to it as yet.” He expressed mild astonishment and “am quite surprised at you holding out so long [Eileen was pregnant] if it keeps on I may have to widen the doorways.… It can[’]t be going to last for much longer I hope.” He asked her to notify the Battalion Orderly Room at Camp Ipperwash “when you go to the hospital … just give them my name and number and ask them to notify me at once, also add Trained Soldiers Coy.… Please take good care of yourself and don’t work to[o] hard.” He suggested it “might be a good idea to send Mike out to J.B[’]s [Joseph Bernard O’Neil, Mike’s oldest brother] a little ahead of time so it will lighten up on your work and it won’t hurt him any to be there for a few extra days …” He assured her that “I[’]ll be thinking of you all the time just waiting till its all over and we have our little bundle from Heaven. I Love you dearest all My love Mike.”

“It[’]s just battle drill battle drill and battle drill”

Early May witnessed more concern about the upcoming birth and his expectation: “I can get a few days off when the baby comes which won’t be half bad.” He took “back what I said about the training I’m damned near tuckered out tonight. It[’]s just battle drill battle drill and battle drill.” A map reading exercise in the field went awry; they missed the timings for the truck and marched back to camp, arriving at 0200 hours. They were up at 0600 for a ten-mile route march and then “to loosen up we had compulsory sports we played ball till 3.30 stiff as old hell, going have a shower with our tounges [sic] hanging half way to the ground. That[’s] army life for you, on the other hand we have our breaks but when they pour it on we know it. Today we were told no week ends. Just a tough major at present.” He offered assurance that “I am fine and getting back in good condition surprisingly fast.” He was a bit short on money and asked Eileen “to send me just a little to carry me on as I might want to get tight one of these nights.” “Well lover,” he wrote, “you just hurry and have that baby.”

“quiet, unassuming fellow who is interested chiefly in doing a good job”

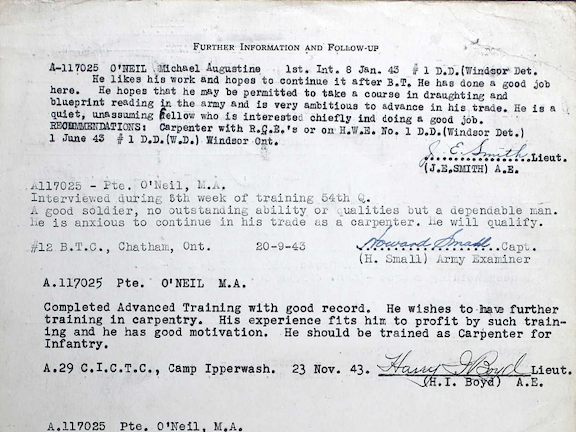

On 1 June 1943 a PSB officer noted:

He likes his work and hopes to continue it after B.T. He has done a good job here. He hopes that he may be permitted to take a course in draughting and blueprint reading in the army and is very ambitious to advance in his trade. He is a quiet, unassuming fellow who is interested chiefly in doing a good job.

“A good soldier … a dependable man”

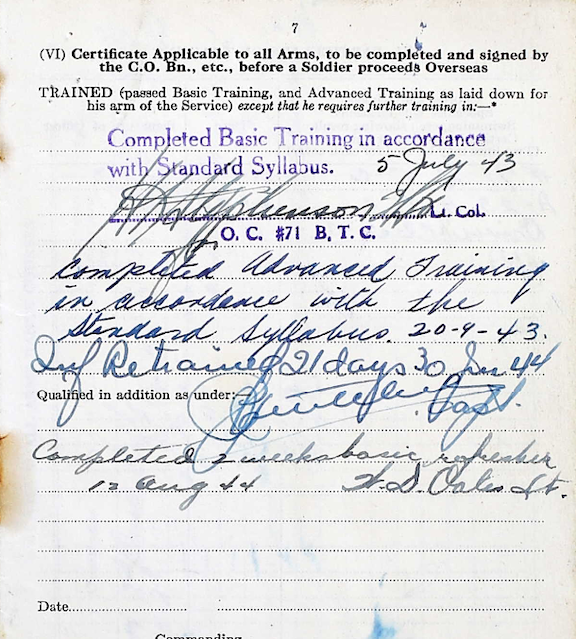

His recommendation followed the path already taken: “Carpenter with R.C.E.’s or on H.W.E. [Home War Establishment] No. 1. D.D. [District Depot] (Windsor Det).” Pte O’Neil received a furlough from 12 to 25 July, and on 7 August, #12 Basic Training Centre, Chatham, took him on strength. He was interviewed again on 20 September 1943 at #12 during the “6th week of training”: “A good soldier, no outstanding ability or qualities but a dependable man. He is anxious to continue in his trade as a carpenter. He will qualify.”

“He should be trained as Carpenter for Infantry”

On 9 October the A-29 Canadian Infantry Training Centre (CITC) at Camp Ipperwash took him on strength. The next interview occurred there on 23 November: “Completed Advanced Training with good record. He wishes to have further training in carpentry. His experience fits him to profit by such training and he has good motivation. He should be trained as Carpenter for Infantry.” There was another interview the next day: “Is a good type. Likes to do his full share … At end of 8th week A.T. [advanced training].” He received a pay increase to $1.50 daily, the full regimental rate on 13 December 1943, and went on leave 10 days later. Pte O’Neil was home in Chatham with his wife and two children for Christmas.

In January 1944, he raised the amount of his assigned pay [the deduction that went to Eileen] to $23. On the 6th, the dawning of the new year took him to Hamilton and the Canadian Army Trades Centre. He received a ten-day furlough from 10 to 23 April.

“suitability of o/s [overseas] in C.I.C. [Canadian Infantry Corps], as Bricklayer, Group ‘C’”

On 26 April 1944, he was at the Canadian Army Trades School (CATS) n Hamilton where he “Qualified as Bricklayer (72%).” Recommended for Group C Trades Test.” On 5 May, he took the test at Camp Ipperwash: “O’Neil has been tested and qualified as Bricklayer, Group ‘C’,” in accordance with “Instructions Regarding Trades Tests and Tradesmen’s Rates of Pay,” effective 1 May 1944. He took home an additional $.25 daily. Ten days later, after testing for full qualifications as a bricklayer, there was yet another interview and examination of his file. They indicated his “suitability of o/s [overseas] in C.I.C. [Canadian Infantry Corps], as Bricklayer, Group ‘C’.” He had six days embarkation leave in May and on the 30th embarked for the United Kingdom. His daughter, Anne Louise [Nan], was born at St Joseph’s Hospital in Chatham on 7 June.

“Bricklayer”

O’Neil had a final interview on 12 June 1944, two days after arriving in the United Kingdom, at #2 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU). The PSB officer jotted down the basics of O’Neil’s life: height, weight, birth date, date of enlistment, married with “2 children … and wife expecting soon,” “Civil trade as carpenter, “Qual bricklayer gp ‘C’,” and “Empl 7 mos as carpenter.” There was more: “Likes construction wrk. Good att. Willing sold.” The recommendation was simple and stunningly obvious – “Bricklayer.” The army ceased paying him $.25 trade pay on 16 June. On 28 July, he went on CMHQ Course 127 ser. 23 (Bricklayer Basic) qualifying as a bricklayer “B” on 31 August 1944. He embarked for France on 7 September and disembarked there the next day when he was taken on strength the X-4 list (unposted reinforcements) as “Bricklayer ‘B’.”

“more lonesome and anxious to hear from you and my little family”

Pte O’Neil wrote his wife from 2 CBRG (Canadian Base Reinforcement Group) on 21 September 1944. “It is,” he opened, “my only pleasure to sit down and write to the one I love.” He hadn’t received either letters or parcels “so I am getting more lonesome and anxious to hear from you and my little family.”

I[’d] give so much just to see you all and see how our little babes are growing.” He was still “in the same place” but had been “warned for draft anytime of day when called for so it means just keeping myself fit and clean. We get plenty to eat, lots of rest and spend our spare time in short marches or go swimming in the channel. It gets tiresome just waiting around day after day as there isn’t anything much for amusement except ball, horseshoe or volley ball … It[’]s a great life; I’ll be so glad when I can get back and do some real work for a change. I don’t know much of the war situation because there is very little chance of getting news but it doesn’t matter a great deal when you get it second hand or doctored up.

The day is not far off when I’ll be probably be getting news right off the printing press and you sit in the trench listening to them tap it out; that’s when it[’]s first hand news. The war has quite a way to go yet I do believe but it’s a hard thing to tell much about it. It[’]s so much of a mystery.

Well my dearest wife your husband is still feeling fine and thinks of you daily and of the glorious day it will be when we are united again. Life will be heavenly to pick up where we left off.

Hug my little Nancy, Mary K + Mickey for me. I love you with all my heart xxx love Mike.

Pte O’Neil was headed to the front. Whether he had any inkling of where he might end up is unknown. His letter to Eileen is typically reassuring, positive, caring, loving, and uncomplaining.

“dark and cold”

For the Argylls, the late days of September provided a much-needed respite from battle. On 21 September, the unit moved to Boekhoute “to take up a position” there. Battalion headquarters set up in a “large, luxuriously fitted out home, that had been abandoned by its owners, advisedly since it had received several direct hits.” B, C, and D companies “took up positions covering the perimeter of the town,” while A “firmed up” at a cross-road a mile to the south. It was “partially isolated” because the road leading to it was flooded with about two feet of water, “the result of enemy inundations.” On the 23rd, the weather, which had been “bright and dry,” turned, with rain and mornings that “dawned dark and cold.”

“the men have had a bath and got themselves new shoes battle dress etc”

On the 24th, the day before Pte O’Neil’s arrival, the Argylls held a church parade at 1130. Lt Norm Donaldson, A Company, wrote to his wife that “it will be good to hear our padre [Charlie Maclean] again. Boy he’s 100%, always right up there with the boys.” Capt Sam Chapman, C Company, agreed: the “Padre is still the same great guy – it was the first good service I’ve been to in months + months.” “Most of the R.C. boys,” he noted, “went to mass right behind this building.” The next day, Maj Alex Logie, B Company, let his wife know that Lt-Col Dave Stewart “says we can more or less have the day off.” The quiet was broken: “we … noisily mortared by Jerry and also his snipers are working overtime and making life very unpleasant.” Later the same day, Logie added that the rest would last “at least 48 hours … the men have had a bath and got themselves new shoes battle dress etc.” Lt Claude Bissell, the unit’s Intelligence Officer and war diarist, described the night of the 25th/26th as “wet and cold.”

“Heavy shelling. Jerry just about 50 yrds from us across the Canal … Very wet and cold. Uncomfortable.”

For the first time, they were aware that “the summer had gone and fall was hard upon us.” During the night, Allied artillery and mortars “repeatedly laid down concentrations on likely enemy gun-positions.” Then, from 1830 to 1930 hours, “a heavy enemy gun, in all likelihood a 105mm, shelled the town, and several of the shells lading uncomfortably close to B.H.Q.” Cpl Harry Ruch, A company, confided to his diary: “Heavy shelling. Jerry just about 50 yrds from us across the Canal … Very wet and cold. Uncomfortable.”

“So anybody looked like he could carry a rifle, we grabbed him”

The unit’s offensive action was confined to small patrols “sent out to capture a prisoner.” Pte Mac MacKenzie, D Company, remembered the patrolling and the depleted ranks of his company:

… we took a shoemaker in because … D … was so bloody badly hammered that I think we were down to forty or fifty all ranks. So anybody looked like he could carry a rifle, we grabbed him: “You’re in, you just volunteered.”

“responsible for the front”

Patrolling continued. As Lt Bissell put it, it was “becoming obvious that our holding role could be continued for some time.” On the 27th, A Company “got a patrol across the canal under heavy mortar fire”; C “failed to cross … since they discovered enemy-manned slit-trenches on this side, about 200 yards ahead of their forward platoon.” They concluded that four men were “in no position either to attack and take a prisoner or to proceed across.…” On the 29th – the day of Pte O’Neil’s arrival – the Argylls moved “in a locality slightly” to the west of Boekhoute. B and C companies and the Carrier Platoon “would be responsible for the front.”

“Bricklayer ‘B’”

The Argylls took him on strength at Boekhoute, Belgium, on 29 September as a “Bricklayer ‘B’.” An infantry battalion may seem an odd unit for a bricklayer and Pte O’Neil was posted to C Company, a rifle company, commanded by Maj Bob Paterson; the CSM was the – by now – legendary George Mitchell. The unit’s war establishment was over 800, with specialized trades and general duty soldiers comprising 283 of the total (2 September 1943); the latter were a considerable majority of that number. There were bricklayers, usually one or two serving with the Argylls and, generally, in the Pioneer Platoon. Pte O’Neil arrived at a critical time for the battalion. From 25 July to 23 September, the Argylls had lost 100 killed in action, 32 POWs, and 305 wounded for a total of 437. The unit’s fighting strength was usually considered about 400 (the four rifle companies). Support Company (the Pioneers, the Mortar Platoon, the Anti-Tank Platoon, and the Carriers) was what Lt Alan Earp (Pioneer Platoon) considers “a bubble,” somewhat isolated from the grievous losses sustained by the rifle companies. The Scout Platoon was also part of the battalion’s fighting establishment; it, too, was something of a bubble (see Pte Tony Mastromatteo; Capt Lloyd Johnston; and Pte Paul “Cosy” Cole). There is a context for Pte O’Neil’s posting to a rifle company, and it relates to the perilous lack of reinforcements after heavy losses. “We were so bloody badly hammered,” as Pte MacKenzie of D Company put it, that they “grabbed” anyone.

“much needed”

The first reinforcements arrived on 4 September and the number was “sufficient” to revert to four rifle companies rather than three. Lt-Col Dave Stewart had amalgamated B and C companies after St-Lambert because they were so badly depleted. The 81 reinforcements who appeared on 12 September were “much needed.” Pte Sam Resnick, a reinforcement, remembered “going up [to the Argylls] … after some minimal training.” Pte John “Mac” Mackenzie, helping with the wounded on that day, recalled one of the new drafts taking in the sight of the wounded and saying, “Boy, it’s tough out there.” Mac replied, “No, it’s not a bad day,” and the young man “went green.” When new reinforcements arrived on 6 October, Cpl Harry Ruch recorded in his diary that he and others were going back to A Echelon (in the rear) “to train” them.

Training was the key, not only for the fighting proficiency of the battalion, but also for the survival of the reinforcements. Maj Bob Paterson, OC of C Coy, struggled to lead a company short of officers, NCOs, and men. Lt Harold Place, B Coy, said, “It was nothing to go out with a platoon of maybe eight people – which is crazy. Where were the reinforcements? I don’t know.”

“they were just hopeless”

Maj Paterson had “no faith in the reinforcements and that’s what I ended up with practically a company of reinforcements, and they were just hopeless.… You’d try and train them, [but] we didn’t have any time.” A/Cpl Burt Eden, B Coy, thought “it always seemed to us older guys seemed to get through and the reinforcements didn’t … [they] didn’t have the real training, like. Or maybe it was just their time, I don’t know. But it takes a long time to get to know when you move and when you don’t move and when to put your head up, when not to. Takes a while.”

“takes a while”

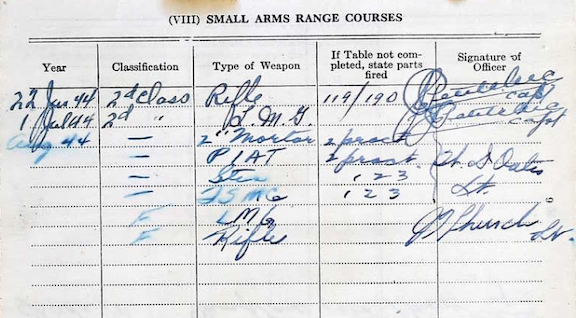

Original Argylls from 1940 and 1941 had “a while.” They had basic training and advanced training before they went to Jamaica in September 1941. There, Lt-Col Ian Sinclair had developed a plan for continuous rotation of companies to Newcastle for advanced training during their 22 months in the sun. Soldiers qualified on all weapons, trained in all aspects of fieldcraft, and took specialized course. In the United Kingdom, the originals along with the old-timers who joined them late in 1943 endured an ever-quickening tempo of training that included conditioning, non-ceasing range work, specialized courses, the introduction of new weapons such as the PIAT anti-tank weapon, mortars, and exercises from the company to the battalion to the brigade to the divisional level. Pte Bill Patrick joined the Argylls and C Company in September 1944. Before his arrival, in addition to basic (5 July 1943) and advanced training (20 September 1943), Patrick had qualified twice on the Lee-Enfield rifle, twice on the light machine gun (Bren), once on the Sten gun, on the PIAT, and on the 2” mortar. Then, he was “Inf retrained” for 21 days as of 30 June 1944: it was followed by a two-week “refresher,” which he completed on 12 August 1944.

By comparison, Pte O’Neil did basic and advanced training in 1943 and qualified on the rifle and light machine gun [Bren gun] in 1944. He was a trained “Bricklayer ‘B’” as of 31 August 1944 and was posted to the X-4 list as such. Why, then, was “Bricklayer ‘B’” posted to an Argyll rifle company? There is no clear explanation. There is, however, an obvious one – the desperate need of those companies for reinforcements. Lt Alan Earp commanded the Pioneer Platoon from November 1944 to when he was wounded at Friesoythe on 14 April 1945. Last year, he wrote me that:

I think that in the ordinary course of events, and assuming that there was a vacancy, O’Neil would have been a natural for the Pioneers. But they were not restricted to trades and I do not know how many received tradesmen’s pay. [John] Dickson [the Pioneers’ platoon sergeant] was a stonemason and a bricklayer, Harry Turner a hard rock miner, but I don’t recall their being paid as such. They certainly behaved as jacks of all trades, with some acknowledged as being especially proficient at certain tasks.

B and C companies (previously amalgamated because of severe losses) needed reinforcements and Pte O’Neil was a qualified rifleman and Bren gunner; he went to C Company.

“well pleased with the Reg. … everyone in the group are like brothers”

Mike O’Neil next wrote on the 29th – “… it’s a long time since I have wrote to you.” He had been “moving from place to place and only staying a short time in each place.” Pte O’Neil was posted to C Company, commanded by Maj Bob Paterson; George Mitchell was the CSM (company sergeant-major).

I am now in Belgium and at last reach the stage we all look forward too. I have been put into a division and [am] well pleased with the Reg. which I am allocated with The Argyll Sutherland Highlanders. Harvey will know what division they are in. I am today going to the front or at least we expect to. The boys that have been around some time say it[’]s not so bad now but all we can hope for is the best so my darling Eileen and babies don’t worry about me as I am in good health and will do my utmost to protect myself as some day we shall all be together again all one happy family.

It is not just ourselves we have to think about in times like this there are thousands more in the same boat and want to be back home too. The war isn’t over yet and will take a few more months and I don’t think you need expect me home for Xmas this year. I have changed friends so often that at present I am with no one with which I started with but have some mighty fine boys that I go around with, there is four of us but everyone in the group are like brothers.

In an infantry battalion, one acquires siblings readily and Pte O’Neil was no different. The weather was changing, a harbinger of what was to come. The companies pulled out on 1 October. The front was “about 4000 yards, stretching from the main cross-roads at Kerselaar east to a point about a mile from our former B.H.Q.” The role was static; on the one hand to watch the enemy and on the other to prevent them from crossing. On 2 October, Capt Chapman, 2ic of C Company, wrote a letter to his wife that proved how “very quiet” the situation was. He “washed my underwear + shirt this morning” hoping that “if things go on I’m going to get me a sponge bath this evening.… And it’s high time too. I’ve never been so dirty in my life.” He had some of “fellows [in his platoon]; he was there for experience out on the hunt + some for wood + some for eggs + some for apples or pears.”

At Kerselaar the weather was “wet and cold.” The British failure to hold Arnhem “led to a general feeling that the war may go on for a few months before the Germans collapse.” In Canada, in September 1944 Conn Smythe railed publicly about the need for conscription and the reinforcements’ level of training, their numbers, and their quality. The resulting furor led to the so-called second conscription crisis. As to whether or not reinforcements had sufficient infantry training, Capt Chapman wrote to his wife on 3 October that if “you could see the service books of the reinforcements we are getting you would know whether he was right or not.” The next day C Company saw a movie, The More the Merrier, and some had showers. For Chapman, it was his first in 12 weeks. “I don’t know how I’ll be able to stand myself,” he suggested, “without the usual B.O.”

“It[’]s not to[o] bad at present where I am so don’t worry to[o] much”

O’Neil wrote on 5 October:

It[’]s a beautiful day here today and we are out in the sun cleaning weapons and ourselves also cleaning up. I am now in Belgium and was for a short while in Holland we move from time to time.

I am feeling fine and eating fairlay [sic] well but you can if you wish send me a parcel something the same as the one before a little canned meats, Jam, sweets, face soap (no [?]) pipe tobacco, cheese & crackers or anything. I would like a small can of corn syrup. You may send a parcel every two or three weeks apart now that I am settled and not being banged around. I am quite sure they will reach me now no cigarettes what ever have arrived but it doesn’t matter as we get an issue every day or seven and when I get what is on the way I will have plenty for the time being. There isn’t anything else I need. I have not received any mail since I left my course. It should catch up soon. I hope so I am anxious to know how you and my babies [are doing].

I haven’t had a chance to write lately so don’t be put out when I don’t write for short periods. I hope you are fine, say hello to all. I must close now as I have to go for inspection.

I love you my Darling as well as my babes.

Will write again soon. I’ll thinking of you first and always. Don’t worry my dear I will try and take good care of myself just pray for me and hope for the best. Its not to[o] bad at present where I am so don’t worry to[o] much.

I send you all my love xxx I love you Mike

“only hope I hold up under the strain when we do get into tougher going”

Three German regiments of the 64th Division faced the Argylls across the canal. Night patrolling was continuous and troops hated it. As Maj Jack Harper, A Company, put it, “you knew that they couldn’t go out night after night after night. They couldn’t stand it.” A diversionary attack on 6 October elicited a violent mortaring of Argyll positions by the Germans. The companies were dispersed along the line. Pte O’Neil scribbled a letter home on the 6th:

I hardly know how to start my letters as there is so little I can tell you and not much in our everyday occurrences worth writing about. I am now enjoying the rest which we are now on but will soon be over again. It sort of gives one a chance to calm the nerves and get your bearings as to what is going on and how they go about it.

It[’]s a great experience, much yet that I have not encountered, and only hope I hold up under the strain when we do get into tougher going.

Fighting does not go on all the time as one would think until seeing it. In between it[’]s just more or less a quite strenuous guard work night and day on some outpost after putting in a certain length of time we are relieved and go back for these rest periods but still carry on guard work, cleaning up our clothes and other little things we have to do.

I feel quite well but only hope my reuhmatism [sic] doesn’t come back on me. No mail yet and anxiously waiting to hear from you dearest one about our little family and everything around home. I do hope everything is going well.

I left my flash light and writing case with Wilfred also my addresses but I don’t think I[’]ll write to anyone except you and Mother and you can notify the rest all I have to say at present. I love you ever so much hope its over soon, but it will take some time yet.

Love Mike

“Love you all, Your Devoted Husband Mike I will not forget Nancy”

Mike O’Neil’s world had changed yet he provided little illumination to Eileen. He allowed that he hoped to bear the strain, but otherwise he betrayed little. The following day he sent a note to his eldest daughter, “Mary K,” to offer “congratulations on your Birthday … daddy was thinking of his little girl and I love you very much.… Daddy is well and thinks of all of you always. P.S. Dear Eileen I have not found what I want for you yet but in my travels will get something for you. Love you all, Your Devoted Husband Mike I will not forget Nancy.”

An Argyll’s life in the field was framed by his platoon or company. Four-man patrols crossed, or tried to cross, the canal at night. On the 10th C Company sent out a patrol led by a new lieutenant, Kerrigan King. It reached the far side, silenced a machine gun post with grenades, and cleared out “a length of trench.” Lt King was fatally wounded.

“the heavy guns are pounding at your ears night and day”

Pte O’Neil found time to write on the 11th. Once again, the war scarcely intruded and he expressed his ever-present concerns about finances and his family’s well-being. Cigarettes and Christmas figured more than the war.

It seems that I never get to writing you as often as I like too [sic] but I haven’t a great deal to tell you as I have not received mail except the ones I wrote to you about. It would make it much easier to write if I knew the score everything in common back home.

At present we are in a rest area but I cannot say it[’]s much of a rest when the heavy guns are pounding at your ears night and day. I suppose the new victory loan is on back home as it is here. One could not help buy them here, as there is nothing to spend money on and nine times out of ten in places where there is no entertainment of any kind. I am sending you receipts of two fifty dollar bonds. One I paid cash for. The other one will come out of my pay which will be paid for at the end of April. They are both addressed to you to put in the Bank with the others to be used only if you need them you no doubt have your hands full paying off the doctor and Hospital. By your last statement you were doing very good and should have it cleared up by Dec.

No doubt you have had other little items of expense in the up keep of everything. One thing I forgot to mention before is that according to my life insurance you do not have to pay the premiums when I am overseas check and make sure and if I am right just add the same amt to our bank account and we will some day be able to use it.

I hope the house renters coming through___ so you can meet the taxes. This fall when you light up the gas stove in the living room take the bricks out and have the holes cleaned, it will give better service and more heat.

There isn[’]t anything more I can tell you. I am all right for money and cigarettes but none have come through from home so do not send any more because the war will be over before I get them no doubt.

The hardest part is finding every one because of the continual moving around one has to go through. I have been able to get cigarettes here for 4 francs so there is no need to send them every day we get an issue of seven cigarettes and one bar also candy so it[’]s not so bad off over here. Sometimes there is none, but lately everything has been coming up very well.

I suppose the Xmas parcels will soon be on the way. Send me one or two bottles of Private Stock in separate parcels. I think they will come through all right. I expect to get my parcels and mail soon but god only knows where I’ll be in another week or so as we keep moving around but now with you having my new address [with the Argylls]. It makes it much easier for everything to come right through to me.

If you can manage to send me a few snaps of yourself and the babes I love to have them, just two or three as I haven[’]t much room to carry more. I[’]ll bet the kiddies are all growing so much and I get so lonesome for all of you at times. It will be a great relief when it[’]s all over won[’]t it love. I will write again very soon. I love you very much as well as our babies. XXX Love Mike

“It gets sort of lonesome at times when I do not hear how you all are”

On the 14th Lt-Col Stewart decided “that the time was ripe for an Argyll crossing of the canal.” The battalion would soon be on the move. Pte Mike O’Neil managed a brief note to “My Dear Wife + Babies” prior to the unit’s advance:

Today the 14th of Oct and still hoping to receive a letter from you. It gets sort of lonesome at times when I do not hear how you all are. I know everything else is OK because I left every thing in good condition so I do not worry in that line. Still in the rest area but not for much longer. Feeling fine and always have you in my thoughts. I love you so dearest one.

One thing I forgot to tell you is do not survey the lots unless you really have to. I haven’t anything more to say at present except I received cigs from Fran + Ursula also the Firemen. Your parcels sure must be going around the world but some day they will catch up. I haven’t wrote to mother lately but tell her I am well and will write soon. Say Hello to every one for me. Hug my babies for me. Lots of Love Mike

“shellfire and small arms”

The Scouts and the Pioneers entered Watervliet having “improvised a foot-bridge.” They had cleared the mines as they went and found “only a few bewildered enemy.” The CO immediately ordered A Company to cross and C Company to “pass through and clear the houses on the road leading northward from the town.” Everything “proceeded smoothly” and by 2200 hours C “had advanced northward from Watervliet about 1000 yards before contacting the enemy, who was dug in along a dike and offered fierce opposition to any further advances. At the same, time they were being subjected to heavy shelling, from which they suffered about 9 casualties.” Maj Hugh Maclean commented that “every day couldn’t be Sunday,” and opposition became more noticeable. By 2200 hours C came to a halt about 1,000 yards beyond the town because of “shellfire and small arms.”

In an interview, Pte Art Bridge, C Company, recalled the night of the 14th and the next day:

…There were a whole series of incidents that got to me. In the night, we were in a small shed under fire and one of the scouts who had been with us, or gone ahead of us, he was outside the little house that we were in and the Germans kept coming and attacking and throwing grenades at us. And this poor guy – the scout – got hit. And I don’t know what his name is, or was [likely Pte Jack R. Reibeling], but I can hear him now crying outside there: “Come and help me.” And we didn’t go and help him and I’ve never forgiven myself for that. That poor guy died out there that night.

“A shell struck it, killing the occupants immediately”

By 15 October 1944, Lt Claude Bissell, the unit’s Intelligence Officer and war diarist also made his daily entries in a similar manner. The small actions and the “brief skirmishes,” regardless of how “sticky and dirty” often went unnoticed. Pte Reibeling’s death on the 14th and C Company’s close encounters with Germans attacking a “little house” with perhaps a section or a platoon passed without remark. So, too, did the shelling and sniping of C Company’s position on the 15th. The former killed Ptes Alexander Nickoloff, Gordon Marr, and Muir Marlatt. HCapt Charlie Maclean, the battalion’s padre, wrote to Lolly Marr, Gord Marr’s wife: “The Germans were heavily entrenched on the other side of the canal. The fighting was very severe, but the Canadians drove the enemy back. Marr and a companion were fighting from a house. A shell struck it, killing the occupants immediately.”

“… general anguish got to me. I couldn’t do anything. Funny feeling”

For Pte Bridge, C Company, the night of the 14th and the day of the 15th were “sticky and dirty” as Cpl Ruch would have it:

The next day, we were getting ready to push on up the road and an artillery barrage came down, and I was shooting out a window of the house and a shell came and hit the house right where I was, and it blasted me – my nerves – bad as a result. It knocked me down and one of the fellows that was with me in the same room. He was sitting on a chair and shrapnel took two legs off the chair and down he went, in that chair. That, and the continued barrages, and no sleep, and general anguish got to me. I couldn’t do anything. Funny feeling.

Pte Bill Patrick, C Company, was wounded at 1000 hours on the morning of the 15th. It was a “G.S.W. (M.G.) [gunshot wound machine gun). Patrick’s condition was “hopeless,” but a surgeon operated late on the 15th; Patrick died six hours later in the early morning hours of the 16th.

Early that afternoon the unit was on the move again for “its new concentration area north-east of Antwerp.” On the 17th, the war diarist laid out the plans for the forthcoming campaign:

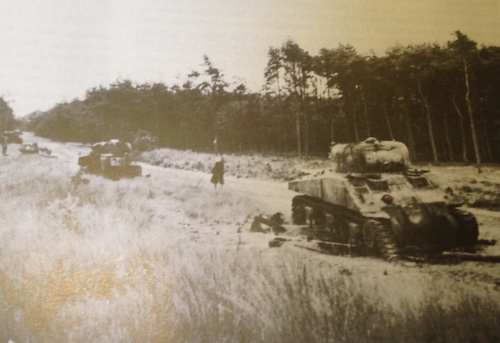

… we were to drive northward from Antwerp and thus complete the process of opening up the great port for shipping. We would likely encounter a mixed sort of opposition – the usual fierce, fanatical rearguards combined with pockets of weary Germans, anxious to surrender. The kind of ground … lent itself well to mines and booby-traps: flat, sandy, and heavily wooded; and, as we were later to find out, the ground was ill-suited to armour. The C.O. also announced that in the afternoon we would move [to] a new concentration area … about two miles north of Antwerp. We reached our new area at 1600 hours.

That day, Maj Alex Logie, OC of B Company, wrote his wife about the long move – some 70 miles:

The country looks a lot like some of our northern parts except that it is much flatter but they have pine trees and maple and poplar and as I look out this window I can see the leaves beginning to turn and it reminds me so much of looking out our window at the lake.… We are together for the first time in months and I heard the pipe band playing at BHQ for the 1st time since I came across the channel and it sounds wonderful …

With the battalion altogether, Lt-Col Stewart held a party for his officers on the night of the 17th. Capt Chapman, C Company, related the night’s festivities to his wife the following day:

…And last night we had a party in a school. They had finally amassed 1/2 bottle per officer of liquor + instead of issuing it out set it all on the table.

The Col. said nobody was to not get drunk + I believe he had his way. It’s awfully silly actually but the responsibility is terrible + a little blow up probably saves nerves.

The troops partied that night as well. ALSgt Earl MacAlister, B Company, told his sister about his platoon’s activities:

…We done a patrol the other day thru what could have been pretty warm territory + at the place where we made our contact with another reg’t my boys found some real good wine + liquor sealed in a wall that a shell had unsealed. That nite we invited the people in whose house we lived, into our two rooms for a drink. One of the fellows started playing a mouth organ + soon everyone was dancing. What a time, we even danced with each other; there was room for three couples to dance at a time but we had five or more so you can imagine just how things went. Our platoon officer came over part way thru the evening + instead of wearing his boots he had just slipped into a pair of wooden scampers. He had quite a time trying to jive in them. The rest of us followed the old tradition of dancing in our stocking feet…

“everything Ok for the present”

Pte O’Neil wrote to “Eileen + Babies” on the 18th:

Hello my dearest one I suppose you have been wondering when I would write again. No mail has come through yet to me except two letters and beginning to wonder if the rest are being held or lost there must be something wrong.

Some day soon I expect to get quite a lot and will sure enjoy reading every one of them.

I am quite well, eating well and getting plenty of sleep and everything Ok for the present and don’t want you to be worrying yourself. I haven’t much to tell you or can I say very much only hoping that everything is going well with my little family.

I[’]d love to be with you on Mary K’s birthday and hope the little parcel I sent arrived on time. It wasn’t much but I haven’t had a chance to get anything else as our stopping places are mostly in the country or near small villages with nothing to sell or buy if one wanted to. I would have liked to shopped around in Antwerp as it is a lovely big city but as usual we just went right on through. I guess there will come a day to do shopping anyway.

I have sent you a letter containing receipts of two bonds I mentioned before and also a form for you to read. It differs somewhat to the ones in Canada. I believe I just mention it again in case the letters didn’t reach you. One fifty dollar Bond cash the other to be taken from my pay. My finances are ok and do not need of anything which you could send.

Say hello to the rest of the family and tell them I[’]m Ok. Hoping they are well also and as busy as usual. I will write to you again in a few days. Until you hear again my dearest one I[’]ll be thinking of you and the babes. I love you very much. Hope to hear from you very soon. Lots of Love xxx Mike

O’Neil finally received his anxiously awaited mail from his wife. He managed to write her on the 21st:

Just a short letter for now to tell you that my back mail has arrived at last also 300 Winchester cigarettes. The snaps were very good also the clipping.

I enjoyed all your letters and sorry to hear about Mr Baker. Tell Lillian I[’]m sorry not to be there for the wedding and presume it is Jack she is marrying as you did not say. I am also very glad you are going to graduate for your B.A. I[’]ll bet you think your [sic] pretty smart to get an A on all your subjects. It will be a big day for you and aunt Alice as she no doubt has been waiting for that day of _____ time. I must congratulate you and only wish from the bottom of my heart that I could share it with you. It will be lovely won[’]t it dearest.

Well this is the only page of paper I have now so I must close. Say Hello to every one for me. I am well + feel fine. Here are a few more souvenirs for you. Will write again very soon. Good Luck my darling Love xxx mike.

“some of its [the Regiment’s] most exhausting, trying and least rewarding battle”

Maj Maclean described the “coming days” of late October as:

… some of its [the Regiment’s] most exhausting, trying and least rewarding battles. Symbolically, summer was ending as the Battalion came back to the south side of the Leopold Canal. Grey, stormy days, bleak mornings and cheerless afternoons, and cold shivering nights lay ahead. The chill wind off the Scheldt blew hard from the north as the Argylls turned towards Antwerp and the country between that city and the Maas river, 30 miles or so away.

“our men were constantly shelled and mortared as they advanced through the woods”

On 23 October, Lt Claude Bissell, the unit’s war diarist, noted that the “weather, which had been dull and cloudy, changed for the better today, and visibility was quite good.” The military situation proved otherwise initially:

The attack began rather unpromisingly. Heavy enemy artillery laid down deadly concentrations on our forming-up areas so that even before the two attacking companies moved off, several casualties were sustained. “B”-Company moved off on schedule, but “D”-Company was disorganized by casualties, among whom was the Company Commander, Major Farmer, and was delayed. The C.O. came forward, personally gave instructions to the one remaining officer, Lt. Ecclestone, so that the company was ready to begin its attack by 0830 hours.

The actual progress to the Holland border involved little opposition by enemy on the ground (those encountered were speedily taken prisoner); but our men were constantly shelled and mortared as they advanced through the woods. By 1100 hours both companies had obtained their objectives and were in position. In the meantime the Lake Superior Regiment and the 21 C.A.B. had been attempting to push on through to our left along the road to Wouwsche Plantage [Wouwse Plantage]. They had encountered very heavy opposition; three tanks had been knocked out; and the forward company … was pinned down about 1500 yards short of the town.

At 2300 hours the C.O. announced to the Company Commanders the bold plan that had been resolved upon to clear the enemy from the Wouwsche Plantage area. The plan was briefly this: A force consisting of two troups [sic] of tanks (22 C.A.R.), two companies of Infantry and the Scout Platoon of the Lake Superior Regiment would assemble as soon after midnight as possible at the farthest point of our penetration along the road. One troup [sic] of tanks would lead, using lights and “flushing” the sides of the road with fire as they proceeded. It was felt that by this combination of power and surprise, a speedy break-through would be achieved.

There were 30 casualties (6 KIA, including LCpl Norman Hubert James, and 24 wounded.)

Over 40 years after the war’s end, Maj Bob “Flan” Paterson reflected on LCol Dave Stewart’s wartime leadership of the 1st Battalion. As early as 1945, when he wrote his history of the lst Battalion, Maj Hugh Maclean thought that the battalion’s style and spirit caught fire at Hill 195 (see Pte Anthony (Tony) J. Mastromatteo and Lt Milton Howard Boyd). It is an action now renowned for its tactical brilliance and warrior spirit at the level of a battalion – no mean feat. Paterson acknowledged the acclaim owing to Stewart, the Scout Platoon, and the rifle companies for Hill 195. But he considered Stewart’s best battles at Wouwse Plantage in October. Paterson provided no elaboration or argument. That said, the context for his assessment derives from his observations on the exhausted state of the battalion by this point, the heavy casualties sustained from late July to mid-October, and the training of reinforcements as well as the lack of time to acclimatize them to battle.

“Casualties had been severe and all ranks were approaching exhaustion”

In the post-war, Dave Stewart had but a few regrets. He wished, for example, that he had put forward more Argylls for decorations. In the aftermath of Wouwse Plantage, he left temporarily for an operation. When he returned, he put forward a recommendation that Maj Paterson receive the military cross. It provides some insight into the events of the 23rd and the 24th:

On 23 Oct 44 the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, after four days of constant fighting, had advanced from south of Camthout [Kalmthout] and had driven the enemy from strongly held positions in a dense wood south-west of ESSCHEN [Essen]. Throughout this advance the battalion had been obliged to deal with enemy groups of which a high proportion of the personnel were parachutists, in prepared defensive positions and under the added handicap of very adverse weather conditions. Many of the most successful attacks had been launched at night. Casualties had been severe and all ranks were approaching exhaustion. At 2300 hrs on 23 Oct 44 the battalion was ordered to continue the attack in the direction of WOUWSCHE PLANTAGE [Wouwse Plantage] the key position in the defences of BERGEN OP ZOOM.

The plan of the attack was a bold one, depending upon surprise and speed in a night attack. Preparations were necessarily hurried, opportunities for reconnaissance were denied and the approach march was along a narrow dirt track reduced to a quagmire by earlier tank movement, and hitherto completely dominated by enemy fire which had obliged other attacking units to withdraw. The night was pitch black, and rain fell in a steady drizzle. A/Major Patterson was commander of “C” Coy, the leading element, and was, in addition, charged with responsibility of forming the battle group consisting of two companies of infantry, two troops of tanks, and the Scout Platoon of the Lake Superior Regiment at the start point, in itself a difficult task under the conditions.

The attack went in at 0445 hrs 24 Oct 44, and by 0515 hrs had reached a point 400 yds beyond the S.P. Surprise appeared complete when a leading tank became immobilized in endeavouring to by-pass a road block, and movement was held up. Simultaneously the force was silhouetted by the flames of houses set ablaze by our own or enemy fire and the road was swept by fire from anti-tank guns, mortars and machine gun fire. A/Major Patterson immediately appreciating that he could no longer depend upon close tank support deployed his infantry on either side of the road and pressed forward until obliged to take up such positions as were available before daylight. During this last advance the leading infantry cleared several houses and deep ditches along the road while under constant fire.

During the following day the enemy repeatedly shelled these hastily occupied positions with air burst and harried them with mortar fire. The forward infantry engaged enemy positions with fire, but were unable to advance further and attempts to reinforce them with other companies to mount a further attack were unsuccessful in the face of withering enemy fire. At 1800 hours, before another night attack could be launched, notification was received that the unit would be relieved by the Lincoln and Welland Regiment. The change-over was successfully completed, and A/Major Patterson managed to extricate his Coy without loss.

“a really terrifying experience”

Argylls involved in the fighting on the 23rd and 24th never forgot it. Pte Sidney Webb, a signaller attached to D Company never did:

… there was two companies in the middle of a forest [the 23rd]… as I recall, there was just under one hundred of us altogether … And we went into a so-called action, we went into a forest, and the idea was the Royal Canadian Artillery was to shell the outskirts of this town [Wouwse Plantage], about a half a mile beyond this forest, and they were to shell for thirty minutes and after which time we were going to go through. But the unfortunate part was that the shells went on ourselves … shelling lasted for exactly thirty minutes. We knew how long it was going to last … and between the two companies we suffered just about exactly fifty percent casualties. For every two men, one of them got hit, including Major Farmer [OC D Coy] … that was a really terrifying experience.

“we took a hell of a pasting”

AMaj Jack Harper, commanded A Company on the 24th:

Bob [Paterson, OC, C Coy] went up, and then we had to secure a road in the middle of the night…. We got through, we got up where we secured this road … we faced an awful lot of small arms fire to start off with … the road was mined and then there was a fairly heavy wooded area, where we thought they [the Germans] were. And we were to move forward and clean that out. And then we got tremendous shelling…. We got a helluva bombardment from the enemy. I know I was … trying to get through on the wireless, to get some artillery and [a shell] … just picked us up – the two of us – and knocked us right across the room and banged us up against the wall. And we were stunned; but, you know, we didn’t have any shrapnel [wounds]…. And then we ended up being shelled by our own artillery … and we took a hell of a pasting.

“the nightmarish fighting”

In the war diary entry for the 24th, Intelligence Officer Lt Claude Bissell painted a picture of the atmosphere, the nature of the ground, and the unfolding of events:

The night was a peculiarly nasty one: pitch dark, with a cold rain falling. The road to the forming-up position, at best only a narrow dirt track, had been churned up by the rain and the tanks into a quagmire. On either side of the road was a deep and low-lying, soggy ground so that bypassing was out of the question. Because of these conditions the group was not formed up and ready to move until 0445 hrs.

At 0515 hours forward elements had gone 400 yards beyond the S.L[start line]., and it looked as if surprise had been obtained. Then the leading tank in attempting to by-pass a road block (a knocked out enemy S.P. gun) became immobilized in the ditch. At the same time, houses nearby were set afire either by our own or enemy fire, so that the whole force was silhouetted. The Infantry (“A” and “C” Companies) were forced by heavy enemy S.A. fire to stop their advance and to deploy on either side of the road. A tank that succeeded in getting forward beyond the Infantry was knocked out by a bazooka.

The position in the morning remained unchanged, with the exception that enemy mortars, hitherto quiet, became very active. Apparently they had the area ‘taped’ [pre-determined grid references for lines of fire]: The road was constantly laced with fire, and tac H.Q. already severely battered during its tenancy by the Lake Superior Regiment on the preceding day, was a favorite Jerry target.

The C.O. felt that it was still possible to obtain the objective, and ordered “B”-Company to come forward and to be ready to reinforce “A” and “C”. At 1600 hours a new attack was launched, but this, too, was unsuccessful. The tanks could make no progress against bazookas and an 88 mm. commanding the approaches to the town. “B”-Company, moving forward, was caught in a mortar concentration, and its Company Commander, Capt. McGivney, was killed [in addition, the A/CSM, Charles MacDonald, was wounded].

The C.O. appreciated that no further attempt could be made … to take the town: The men were exhausted by the nightmarish fighting at the beginning of the operation and by the constant battering to which they had been subjected by enemy mortars. Finally, their tank support was virtually gone. At 1800 hours we were informed that our forward companies would be replaced by two companies of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment.

There were 13 killed in action and 20 wounded from C and B companies. Pte Sam Resnick, a recent reinforcement to C Company, was asked “to go and take a message to him [LSgt Patrick F. Stephenson]. I can remember distinctly crawling through the trench … and some of the men had shit themselves … so I was trying to go and find him, and he’d been hit and he was lying on top [of the trench]. Stephenson was dead. ACpl Burt Eden, B Company, noted that “I didn’t even get into the town [Wouwse Plantage]. I was in the ditch, then the tank shot the church steep off and they put the shells right in the ditch and they got me …”

“the first thing I saw was a jeep-load of dead men”

During the night A and C companies “returned to the old positions that they had occupied on the 22nd. The 25th “was a day of relaxation” for those who survived. That day, Maj Gord Armstrong arrived to take over B Company that had lost two company commanders in four days [Maj Alexander Chisholm Logie and Capt Raymond G. McGivney]. Capt Hugh Maclean, wounded on 2 August, also returned. Both officers had immediate, powerful, and visceral reactions to the state of the battalion and the sights that met their eyes. “I don’t think,” Armstrong later recalled, “I fully appreciated what it [battle] was like until I walked out with [Padre] Charlie Maclean … and I saw these twelve bodies waiting to be buried.” For Maclean:

…the first thing I saw was a jeep-load of dead men. When they let me out, here was a jeep of our people. And they were all covered with blankets and all we saw was the boots sticking out. Some return.

“And on the verandah there were four bodies covered over”

Pte Donald Stark was posted to the battalion that day:

I arrived and … as usual guys were screwing around, just sitting around waiting to see where they were going to go. And on the verandah there were four bodies covered over. So when you look at them, you know what they are. This is your first glimpse of maybe your own future, and you think about it. But you get used to that too.

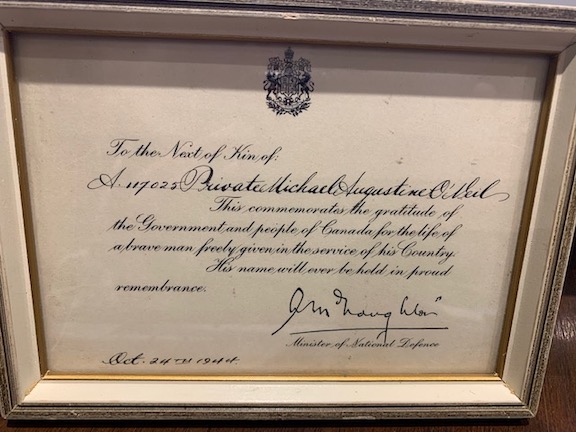

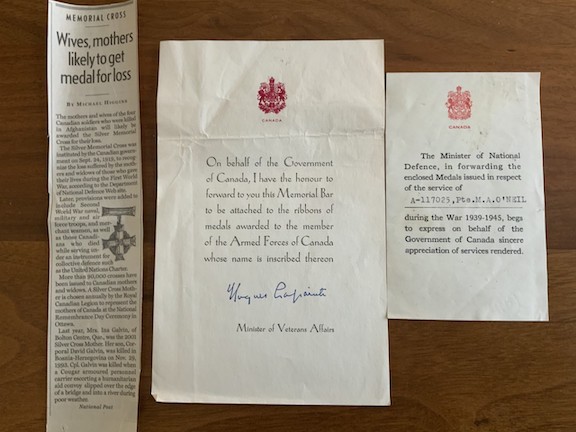

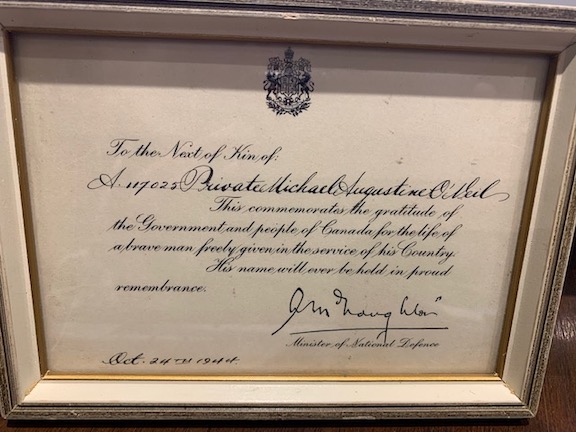

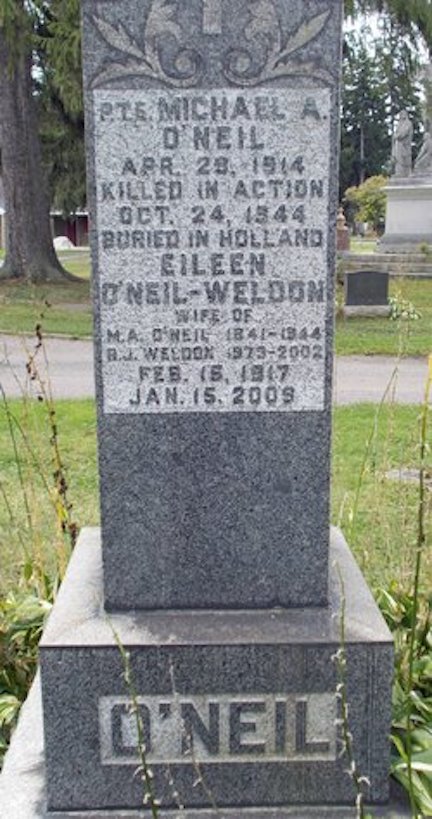

Pte Mike O’Neil’s war ended that morning in the dark, dank forest illumined, at times, by burning buildings and reverberated by mortar and artillery fire, and ringing with the staccato of small arms. According to his platoon commander, he was killed by small arms fire and “died at once.” As Lt Bissell put it, “nightmarish.” He was another grim Argyll statistic now enlisted in Padre Maclean’s “shadowy company of the dead” (Bissell’s expression). His body, along with those of his comrades, waited for burial. It did not come until after the end of fighting on the 29th. Between the 23rd and the 29th, 32 Argylls were killed in action and 93 wounded. Pte O’Neil was buried on 31 October 1944 at Huijbergen, Netherlands, on the “SW of Church Corner on Rd to Bergen op Zoom.” Maclean buried Argylls with dignity. They were, as Lt Alan Earp recalled one such service, “brief and to the point … no one spoke other than the Padre” and an Argyll piper played “Flowers of the Forest.”

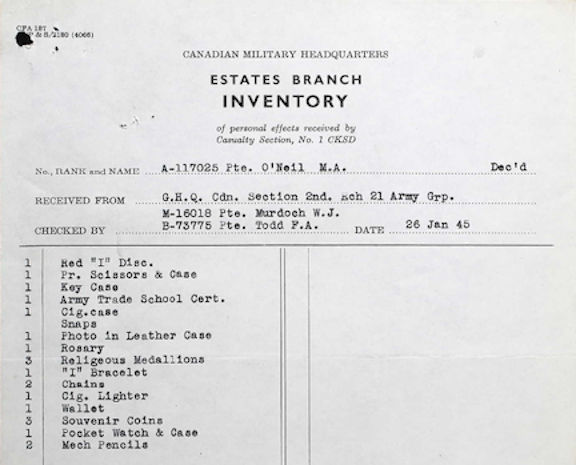

With the burial, the Argyll family moved on. HCapt Maclean helped to sort personal effects, wrote letters to family, and filled out the paperwork relevant to the burial, the death, and the estate. He left his identity disc, a pair of scissors and a case, a key case, his “Army Trade School Cert.,” a cigarette case, a cigarette lighter, “Snaps,” a photo in a leather case, a rosary, 3 “Religious Medallions, two chains, an identification bracelet, a wallet, three souvenir coins, a pocket watch and case, and two mechanical pencils. In due course, the family received a soldier’s personal effects.

“knew something was wrong”

There was a lag in notifying Mike O’Neil’s family. His children, however, relate their mother’s and grandmother’s premonitions of his death. Daughter Mary Kay O’Neil recalls that “Mom woke up at the time Dad was killed and his mother at the same time.” They “knew something was wrong.”

“Mom screamed and ran upstairs”

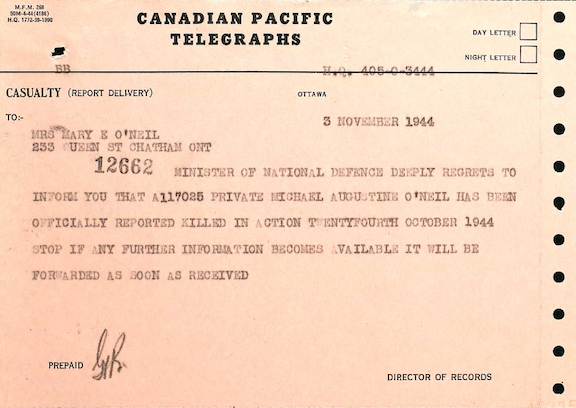

Eileen O’Neil received the life-altering Canadian Pacific telegram on 3 November: Private Michael Augustine O’Neil has been officially reported “killed in action.” Mary Kay remembers “Mom screamed and ran upstairs.” “Grandpa O’Neil came in and consoled Mom.” Letters and other correspondence, both regimental and official, arrived afterward.

“killed in action”

“a good soldier who could be counted on when the going was toughest”

“the deepest sympathy all of us in the A and S.H. of C, too [sic] you in your great loss.”

Capt Sam Chapman, 2ic of C Company, wrote to Eileen O’Neil on 7 November 1944:

I hope you will find some comfort in this letter even though it brings news of your husband’s death.

It happened at night towards the end of October when the company was held up near a cross roads. The platoon in which he soldiered was ordered to try to outflank the enemy from the right. Bravely they went and succeeded in reaching a good fire position. German small arms however sprayed them and here it was that he made the supreme sacrifice. His platoon officer told me that he died at once and did not suffer. Our good Padré MacLean buried him near the little village of Wowshe Plantage in___lland, north of Antwerp.

I did not know your husband particularly well myself – but I knew him for a good soldier who could be counted on when the going was toughest. Before writing this I talked to several of the N.C.O’s who knew him best and they were unanimous in saying what a source of strength and cheerfulness he was to the whole platoon.

In closing I can do no more than express the deepest sympathy all of us in the A and S.H. of C, too [sic] you in your great loss.

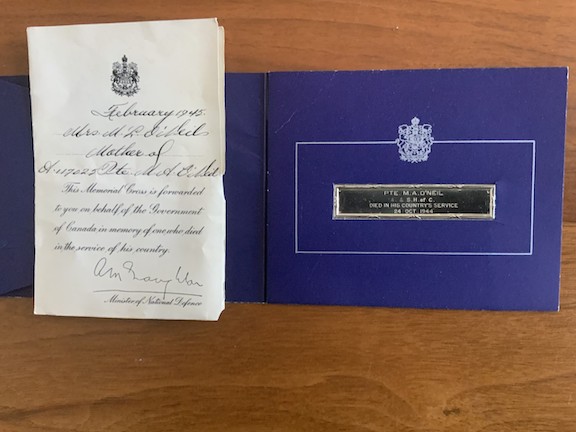

Letter from Minister of National Defence to next of kin.

Letter from Minister of National Defence to next of kin.

“Mothering Alone”

There were several dimensions to the lives of women widowed by the war. The first was financial. Usually, their husbands assigned a portion of their pay to them. With death, they received what was owed and the possibility of some future support for their children. Few Argyll families owned property; most were renters. Secondly, there was the emotional burden wrought by grief over a life with, as Chapman put it, “an end, but no conclusion.” Wives had been separated from their husbands in terms of both time and distance. Telegrams announcing death in battle shattered all hope for the future. Prospects were now bleak financially and emotionally, and, hence, the challenges were significant. Some women remarried and quickly (see Capt Lloyd Johnston); some never (see LSgt Jess Victor Grey); some within two (see LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr); others within five (see Capt John Shirley Prugh), and some had great difficulty in coping (see ACpl Coningsby Cameron Gooderham).

In 2022, psychologist/psychoanalyst Dr Mary Kay O’Neil published Mothering Alone: A Plea for Opportunity. It was, she wrote, “the generosity, courage, and strength of the mothers, who told their stories openly and honestly, that provided the true impetus for the book. They represent the many women mothering alone who struggle to provide a good life for themselves and their children.” There is an added dimension to the impetus for Dr O’Neil’s scholarly work. She dedicated the book to her own mother, Eileen O’Neil (d. 2009), widowed at 27 with three young children: “To my mother Eileen,” she writes, “who alone mothered three children.” “She was,” Mary Kay declared, “a strong presence in my life.” In fact, we “were all close to mother.”

Eileen O’Neil owned the family home at 233 Queen Street, Chatham, with her husband – “joint with wife.” The valuation on the home was $3,200 and they also owned “Vacant Farm Land” valued at $500. They also had a joint bank account. As in most instances, her husband’s life insurance policy (with Confederation Life) “was not good once he went overseas and [the premiums] returned.” Mary Kay remembers that “Mother had property, an orchard and they were planning to build houses [on it].” Eileen had gone to “teacher’s college but couldn’t get a job.” She “had one year of university [the then University of Western Ontario] and finished it by extension three days before father died.” At a time when female enrolment in post-secondary education was less than 20 per cent of the total, Eileen O’Neil stands out. Moreover, she did it during the war while raising three young children. She taught high school in Chatham, and the grade 13 English prize there was named after her.

“very lonely,” with “high moral standards,” and “strong”

Eileen O’Neil had a small financial foundation, she was well educated, and she was strong and resolute. But, there was more. Mike O’Neil commented that “the family stuck together, pretty well, but, in the long run, she [his mother] was alone.” They often went to their uncle’s farm outside of Chatham and all members of the family “kept in touch with Mom.” In spite of the loss of her husband, Mary “always mentioned him.” Mary Kay says, “Mom always made him a real person … I always felt I had a father.” “Mom raised us by herself,” Mike observed. Mary Kay added that she “raised us as she and Dad would have. It was a good upbringing.” “Mom was very thrifty, sewed, and baked.” Faith played a role, an important one, in sustaining Eileen O’Neil and her family. Mike notes that “she was very lonely,” with “high moral standards,” and “strong.” “Her faith,” he says, “held her together [and when she needed to] she turned to a priest.” Mary Kay agrees that “Mother had strong faith [and] said rosary every night.” Nan (Nancy) Eichenberg added that “Mother paid to have four stained glass windows dedicated to Dad” in their church.

“affected more than people are aware”

The loss of his father, Mike said, “affected me quite a bit. I carry it with me every day.” His Uncle Maurice O’Neil “filled in a bit, he introduced me as Mike’s son. I often wish I had the male guidance. I feel it affected more than people are aware.” For Mary Kay, the effect upon her of losing her father and watching Eileen “mothering alone” is “hard to say. I’m a psychiatrist and worked through the effect on me. I didn’t marry until later. I didn’t want to end up like my mother alone with three children. It terrified me. When I passed the age that she was widowed I was alright.”

Remembrance was a fact of life for the O’Neils. “When young,” Mary Kay remembered, “I was always careful to get a poppy and make a good donation. I know how meaningful it is. It gave me an appreciation of sacrifice. The Dutch [the family that tended Pte O’Neil’s grave] were very close. The De Mooijs in Bergen op Zoom, …. were so significant and supportive to us through the years. [I] visited his grave several times. It was emotional in a quiet way. My husband and I visited Juno [Beach]. [We] took the kids to Holland.” “Children whose fathers died in the war have a sense of pride,” she suggests, “he died for a purpose. The Dutch family provided an example because they were so thankful.”

“Mother kept him alive as a person and always talked about him”

The family visited the grave in 1965. “When we visited his grave, tears sure hit me, it was real,” Mike recalls. A Dutch family tended the grave. “Mom had friends who spoke Dutch,” Nan noted, “and they would translate their letters.” “It was hard on her,” Nan commented, but very important,” and it gave Nan “a little bit of closure.” “Mom always made him a real person, we went there, heard the story,” and “made us feel we were close to him. Mom was always so proud of him.” Mary Kay’s perspective is similar. “Mother always told us what a good man he was and how proud he would be of all of you. It was a loving marriage and I always carried that with me.” She “very much kept his memory alive in a good way, it was important to us.” “She wanted to raise us like my father would have.” In short, “Mother kept him alive as a person and always talked about him.”

She remarried (Dick Weldon) “when she was 56, but even during her marriage she never stopped talking about my Dad.” At Remembrance Day services in Chatham, when taps was played, “Mom tightened up and cried.”

For his permanent grave marker, Eileen O’Neil wrote this inscription, a personal tribute to their love and their place in the world, and her hope for his everlasting peace:

BELOVED HUSBAND OF EILEEN O’NEIL

CHATHAM, ONTARIO, CANADA

R.I.P.

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – the Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family.

“a history bought by blood” – Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Note: Pte O’Neil’s poppy will be mounted in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (top) for the Field of Remembrance.

Pte Mike O’Neil.

Pte Mike O’Neil.

Parents Edward O’Neil (1875-1927) and Mary Louisa Faubert.

Parents Edward O’Neil (1875-1927) and Mary Louisa Faubert.

Dover Centre, June 1929. Michael O’Neil is standing at the far right.

Dover Centre, June 1929. Michael O’Neil is standing at the far right.

St. Luke’s Road Barracks, Windsor, Ontario, 1941.

St. Luke’s Road Barracks, Windsor, Ontario, 1941.

St. Luke’s Road Barracks.

St. Luke’s Road Barracks.

St. Luke’s Road Barracks.

St. Luke’s Road Barracks.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, Chatham.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, Chatham.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, another view.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, another view.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, respiration drill.

No. 12 Basic Training Centre, respiration drill.

Camp Ipperwash.

Camp Ipperwash.

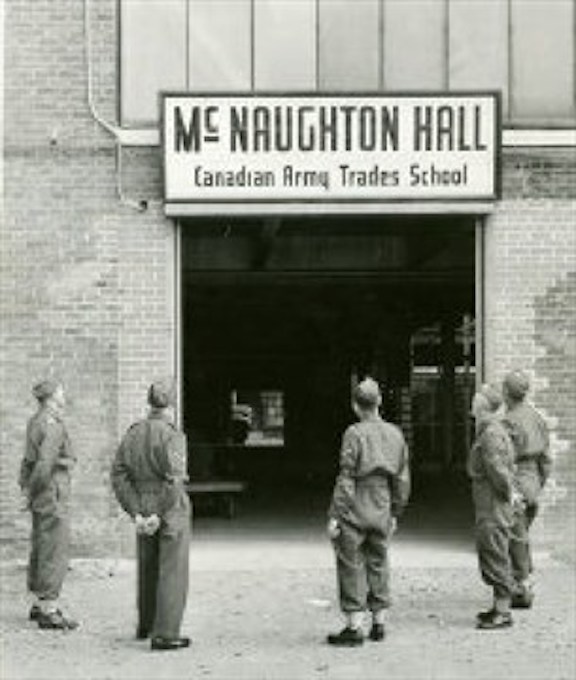

Canadian Army Trades School, Hamilton, 1939.

Canadian Army Trades School, Hamilton, 1939.

Canadian Army Trades School, Hamilton, 1943.

Canadian Army Trades School, Hamilton, 1943.

Marriage certificate: Michael and Eileen O’Neil, 18 January 1941.

Marriage certificate: Michael and Eileen O’Neil, 18 January 1941.

St. Joseph Church, Chatham, Ontario.