Pte Joseph Paul Hall (1917–44) (B 124590)

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

After the “nightmarish” fighting on the 23rd and 24th of October 1944, the battalion had the slightest of respites on the 25th, but even relaxation was interrupted by periodic “heavy enemy shelling.” Clearly, the notion of relaxation in the front lines is a relative concept. On the 26th, the unit moved again. The battalion was tired and they – the “originals” and the “old-timers,” as Lt Alan Earp has described them – knew it. The fighting takes its toll, the casualties loom over the battalion’s existence, the magnitude of the casualties hobbles the unit’s ability to sustain itself in the field, and the inexperience or lack of training of some reinforcements, when they finally arrive, exacerbates an already troubling situation. There was, to repeat Maj Hugh Maclean’s insight, a battle to be won, or lost. The battle weariness of a unit may not have been obvious to reinforcements, but to old Argylls, who had survived, it was palpable and shockingly so. Hugh Maclean was the first Argyll officer wounded (on 2 August). When he returned on the 25 October, he was shocked. For Maj Gord Armstrong, who also returned to the unit on the 25th after recovering from an injury in England, the image before him was unbelievable, visible, and tangible. Argylls were enervated by three months of fighting; they had, to be sure, written new pages of the Regiment’s history, and almost all were written in blood. As I mentioned in the introduction to the entry on Pte Jack Robert Reibeling, the challenges of battle to a battalion’s ability to “do a job,” as Lt-Col Dave Stewart would have it, are myriad, and the weariness that results is surely one of the most challenging. I am reminded of Hamish Henderson’s lyrics to Pipe Major James Robertson’s “Farewell to the Creeks.” The lyrics, in Scots, refer to the 51st Highland Division’s farewell to the fighting in Sicily in 1943. Simply put, the “poor bloody soldiers are weary.” And there were two very bloody days awaiting them on the 28th and 29th.

In 2019, Bob Hall wrote then RSM Grant Lawson inquiring about his uncle, Joseph Paul Hall. In his reply, CWO Lawson copied me. I offer my thanks to him for first spurring my interest and then providing information. I acknowledge CWO Lawson’s effort in moving this research in my direction.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

“… the first thing I saw was a jeep-load of dead men”

War Diary. 25 October 1944. Belgium [C.T.B.]

During the night the companies returned to the old positions that they had occupied on the 22nd…. At 0800 hours the Battalion came back under command of 10 C.I.B., to the great relief of all.

This was a day of “relaxation”, its success limited by the facts that the troops had been very late in arriving and could get little sleep and that heavy enemy shelling continued from time to time during the day.

At 2300 hours we received the message … that at 0800 hours on the following day, we would concentrate at Centrum, a small town South-West of Wouwsche [sic] Plantage, and from there move north-westward towards Bergen-Op-Zoom.

Interview. Pte Donald Stark. C Coy

[Stark, a reinforcement, was posted to the Battalion on 25 October.]

They were in a farm, C Company. So we went into the barn up on the hill. [The enemy was] shelling us, and the truck got hit, the vehicle got hit. So it’s kind of strange, especially being shelled. But you figure, “Well … [it’s] not going to hurt me. Might get somebody else, but it won’t hit me” … [But] you’re there; you’re captive, you might say; and you make the best of it. So you get adjusted to this … very quickly. I remember Tuesday I arrived and … as usual guys were screwing around, just sitting around waiting to see where they were going to go. And on the verandah there were four bodies covered over. So when you look at them, you know what they are. This is your first glimpse of maybe your own future, and you think about it. But you get used to that too.

Interview. Capt Hugh Maclean. Carrier Officer

[Maclean returned to the Battalion after having been wounded on 2 August.]

… the first thing I saw was a jeep-load of dead men. When they let me out, here was a jeep of our people. And they were all covered with blankets and all we saw was the boots sticking out. Some return.

And [I] went over to the Carrier Platoon, and they seemed to be overjoyed to see me. It was so lovely. And they were just serving out in these mess tins…. So I … was served something. And at the moment, there was a mortar shelling going on maybe fifty yards away in the woods, something like that. And then one came quite close, and I remember I was holding the stuff in the mess tins like this, and when I came down I went “Umph,” and the stuff went right out of the mess tins and back into those [same] tins. And I looked quickly at [Sgt] Foster. Nobody said a word. Nobody laughed or anything … I thought, “Okay, I’ll just have to get a hold of myself.”

Interview. Maj Gord Armstrong, OC, B Coy

[Armstrong, an original Argyll, rejoined the unit after recovering from a leg injury sustained earlier in the year.]

I don’t think I fully appreciated what it [battle] was like until I walked out with [Padre] Charlie Maclean … and I saw these twelve bodies waiting to be buried. And you know, this is when [I thought of] going to the CO and saying, “I’ve decided I want a change of occupation,” because two of them were predecessors from B Coy [A/Major Logie, KIA 20 October, and Capt McGivney, KIA 24 October]…. And when I met them [B Coy], the skin was that rather yellowish hue, and unshaven. They looked like a bunch of ragamuffins.

Interview. Capt Hugh Maclean. Carrier Officer

I think the Regiment was tired, really getting bushed …

Interview. Pte Anonymous. 18 Platoon, D Coy

We were really tired by the time we got to Bergen op Zoom…. I was at the stage where I didn’t think we were going to make it at all.

Interview. Major Pete Mackenzie. OC, A Coy

I think he [Stewart] was tired, as everybody was…. But he still had the same spirit and determination. I think it’s fair to say that he was tired of the war at that point. And who wasn’t?

War Diary. 26 October 1944. Holland [C.T.B.]

Lt. Col. Stewart left today to undergo an operation. It was expected that he would be away for 10 days, and during his absence Major Stockloser took over command…. On contacting the Algonquins, who were working north of our … area, we discovered that it would be impossible to concentrate in Centrum, since the Algonquins were working in that area and had by no means cleaned out all enemy opposition.

We were then ordered to work from our present base, about two miles south of Centrum, and strike out north-westward along a dirt road that offered an alternate route to the main north-south highway into Bergen-Op-Zoom. Two companies of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment and two troups [sic] of the S.A.R. had already worked their way well up the road. It would be our task to clear the heavy woods to the right. To do this we would have to cross an anti-tank ditch about 1000 yards from the start-line, and it was expected that the woods would be booby-trapped and mined. Known enemy mortar positions were in a large sand dune just behind the anti-tank ditch.

The plan was this: Two companies, ”A” [Major Mackenzie] and “B” [Major Armstrong] were to advance through the woods, clearing as they went, and to cross the anti-tank ditch frontally. A third company, “C” [A/Major Bob Paterson], was to advance along the main axis, the dirt road which skirted the woods on the left, and was then to turn right and outflank the anti-tank ditch. Each company was supported by a troup [sic] of S.A.R. tanks.

“A” and “B” … moved off shortly after noon. They found the going extremely tough and progress was slow: booby traps impeded their progress and accurate mortar fire … immediately to their front caused casualties. By nightfall, however, both companies had reached the line of the anti-tank ditch. At 2330 hours, “C” … following a heavy artillery concentration, began the “left hook.” During the afternoon the road became temporarily impassable: two AVRES – Churchill Tank Flame Throwers – were completely knocked out by mines, and these, along with several tank casualties from earlier fighting, blocked the road and made it necessary for the Engineers to devise bypasses.

[KIA: Pte Joseph P. Hall. Wounded: 5.]

Interview. A/Major Bob Paterson. OC, C Coy

Stockloser called me in and … first thing he said, “You don’t like me, do you?” Now there’s my [Acting] Commanding Officer, and I didn’t know what the hell to say, because I didn’t like him … the conversation just dwindled out and I went back, but that was … the way he was. But he put me in lead company…. I don’t think he did it out of spite or anything because I didn’t like him, but he just threw me in and that was it.

… a divisional attack would end up with say me as lead company hitting the enemy, and I could never figure that one out. Or a brigade attack. There are so few troops on the ground, leading and hitting the enemy, it just didn’t make any sense to me. And I was very bitter about that. Of course, we had few troops, maybe fifty to sixty people in a company, at the most. Sometimes maybe seventy. Sometimes forty-five. Sometimes thirty-seven. But it seemed pitiful to me that we were told to do this and hit the enemy on a brigade attack front with such few troops. Of course, Stockloser was ordering me about in those days. I mean, why couldn’t they hit with say three companies forward instead of one? We always seemed to go with one…. And the rest of them strung out behind you. Shit, you didn’t have a hope in hell. And I was very critical as I went on, and I got worse. The longer I was in the line, the worse I felt about the goddamn command set-up … I gave up trying to be logical after a while.

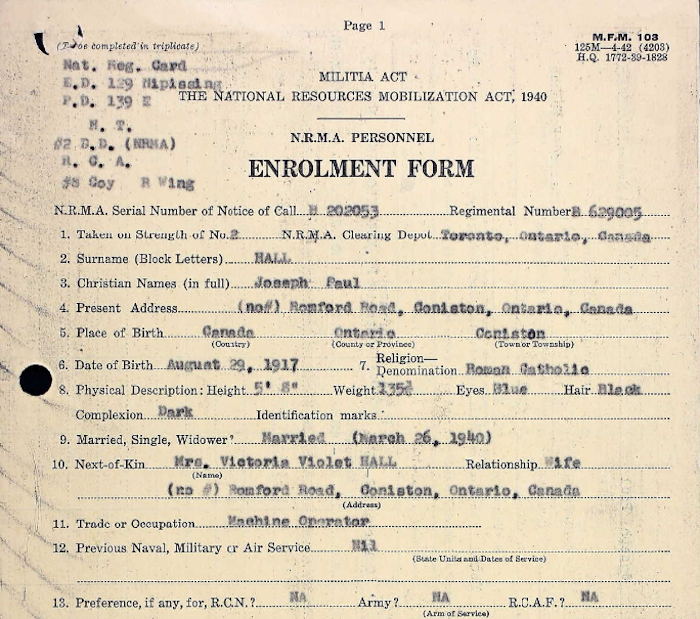

Pte Joseph Paul Hall (1917–44) (B 124590)

KIA 26 October 1944

“Due to the exigencies of the service, he is now considered fit for overseas movement”

John Michael Hall (1873–1930) was born in Quebec and of Irish extraction. Agnes Elizabeth Jenkins (1896–?) was from Wales and came to Canada in 1910; they married in Sudbury, Ontario, in July 1915. Joseph Paul Hall was born on his family’s mixed farm in Coniston on 9 August 1917. The 1921 census indicates that they owned the farm, lived in a wooden house with five rooms, could read and write, and were Roman Catholic. On his military occupational history form, Joseph Hall stated that he had “14” years’ experience working on a mixed farm and considered himself “competent” to operate a farm. He had a grade 8 education and had left school at 15 in 1931; his father died the year before; his conduct during school life was “average.”

“normal”

Clearly, the depression and family circumstances combined to explain his early, but not uncommon, departure from school. His mother remarried Angus Bechamp (by 1945 she was “now Mrs. Elizabeth Benson”). He had a younger sister, Bertha Lilianne, and brother, James. He had three half-sisters: Elizabeth, Violet, and Mary Ellen (the latter two had both died by the time of his enlistment.) Joe Hall also had “7 brothers or sisters [who] died in infancy or prematurely. Impossible to get names.” Later, contrary to what one might have expected, a personnel selection board (PSB) officer described the “status of [Hall’s] home in childhood” as “normal.”

“$40 weekly”

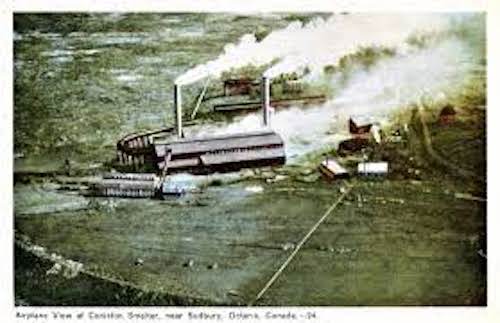

In 1933 Hall started working at International Nickel in Sudbury; first as a labourer, and then for four years he operated cranes (“75 tonners”). It was good work and paid $40 weekly. In 1938 he fell ill with “double pneumonia” and was hospitalized for two months. He married Victoria Violet (her birth name is unknown) on 26 March 1940 in Coniston, where they lived; they owned their own home on Romford Road, and had two children: Thomas Victor Hall and William Gerald Hall. As his personnel record shows, he had no experience with vehicles save as a teamster with a team of horses. He enjoyed hunting, fishing, and softball; his hobby was woodworking. Although promised his job after the war, he desired to “operate his own farm.” He had mixed farming experience in northern Ontario.

“Went Active after 1 month in N.R.M.A.”

From 1 March to 13 April (one source has 15 April) 1943, he performed compulsory military service under the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA). Other Argylls such as Pte Jack Reibeling began their journey to the battlefield as NRMA. Total war and its demands upon the Canadian army and Canadian politics transformed Hall’s life. Once conscripted, he preferred enlistment and readily accepted his new reality. As his personnel record notes: he “Went Active after 1 month in N.R.M.A.”

“a cheery, likeable disposition and makes good conversation”

Pte Hall underwent his first PSB interview on 5 March 1943. The officer’s appraisal read:

This recruit is of limited ability. He has a cheery, likeable disposition and makes good conversation. He appears to be in normally good health but says he is underweight … long hours in smelting plant [he explained] have kept his weight low. He would appear to be a steady, hard working labourer. He is temperate in habits, willing and co-operative and appears to be of average stability. He has no particular hobbies, is married and has one child. He should be capable of completing normal basic training.

“Infantry Other by direction of the O.C.[Office Commanding]”

Enlisting on 13 April, he did basic training until 3 June. He assigned $20 monthly of is pay to his wife; he would later increase it to $23; upon joining, he made $1.30 daily. At enlistment, he was 5’, 8” with “greenish” (other examiners described them as blue) eyes and black hair; his health was “fair (nervous)” and he had “one curious tooth.” Early in his training (two weeks), an officer wrote: “Hall is trying hard to be a good solder. He is slow and not too bright according to his instructors, but is a good mixer and a willing worker.” He was allocated to the “RCA (field),” then reallocated to “Infantry Other by direction of the O.C.” less than a month later. The comments about Hall’s intellect should be understood within the context of various factors: family farming in northern Ontario, the depression, the death of his father, and the necessity to leave school after grade 8. His situation was hardly a rare one for Argylls, and quite often they were unprepared for the written tests required of them and performed poorly.

“Due to the exigencies of the service, he is now considered fit for overseas movement”

On 30 July 1943, the army examiner wrote:

This soldier has met all the required standards during his short period of Infantry Corps Training. Due to the exigencies of the service, he is now considered fit for overseas movement. Infantry (R) Rifleman Non tradesman.

The authority for the order “due to the exigencies of the service” derived from “H.Q. A.G. secret radiogram (Org. 4061) dated 13th July 1943.” It was the same authority and the same rationale for changing the direction of Pte Ira Hedman’s military path.

“Infantry Other – Non-tradesman. (Field)”

The losses suffered by Canadian infantry battalions in Sicily and Italy spurred the reassessment of casualties and the realization that operational units would require large numbers of infantry reinforcements to remain effective in battle. Months later, a personnel officer would review his history as a large crane operator and mark his skill level as “Good.” At an earlier time, it would almost certainly lead to a trade qualification. Hall proceeded to advanced training until 9 September 1943; he went overseas, joining the 4th Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU) in the United Kingdom on 14 September. The officer recommended: “Infantry Other – Non-tradesman. (Field)[.] All of his training was directed towards the infantry; he wished, however, anti-tank (AT) training on the 6-pounder AT gun (each infantry battalion had one AT platoon in its Support Company). An officer described his attitude to service as “normal.”

“Inf – G.D” [Infantry – general duties]”

On 28 September 1943, the personnel selection board officer found him: disposition – “cheerful”; appearance (grooming) – “fair”; and physical appearance – “tall, well built.” “Stability seems good. Learning ability is low. General information is fair, but he may be slow.” As for possibilities within the army, it was “Inf – G.D” [Infantry – general duties]. Along with ACpl Coningsby Gooderham, he joined the Argylls on 30 October 1943 at Riddlesworth Camp after the battalion had returned from a week in the field on EX GRIZZLY II (“battle manoeuvre in conjunction with tanks … with all rifle companies engaged”). It was “cold,” “wet,” and “miserable.” That said, for Capt Bill Whiteside, OC, of the AT Platoon, it provided valuable lessons in terms of “supply, living conditions, self-reliance that was developed; use of food; preparation; health; [and the] proper digging of latrines for all the right reasons and in the right places … Living in huts … doesn’t really come too close to being the real thing.”

It was quite the introduction to the Argylls. The day before, Sgt “Jock” Rennie had died heroically in a training accident (he was later awarded the George Cross, one of eleven that went to Canadian personnel during the war and the only one to an infanteer) – the mood of the unit was “sombre.”

“a quality that perhaps best expresses the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment”

For the “cheery and likeable” Hall, he almost certainly adapted to his new circumstances quickly, although there was not much of a choice. On 1 November, Lt Milt Boyd, the unit’s Intelligence Officer and war diarist, reported that after reveille “at the dusky hour of 0500 hours” and a “hasty breakfast,” the unit moved into the field for the next battalion exercise, BRIDOON. Three days later, still in the field, it was over and Argyll spirit flamed (literally):

Spurts of flame from bonfires knifed holes in the surrounding darkness. Singers, accompanied by mouth organs and even one guitar, blended with one another from different sections of the grove.

Argyll sing-songs have a peculiar character of their own it would seem. Starting quite spontaneously at any time or place, the selections range from Scottish ballads to Jamaican folk songs always latterly sprinkled with the popular ditties of the day. When asked and abetted by the soft glow of a camp fire they have a quality that perhaps best expresses the character and camarad[er]ie of this Regiment.

The next morning, after reveille at 0430 hours, the battalion moved to its new headquarters in Uckfield, Sussex. Hall was in one of the four rifle companies, almost certainly A or B (probably A). Exercises and training at all levels, punctuated by dances and occasional leaves, marked the contours of Argyll life in the days and months leading up to the invasion in June 1944. By February 1944, Victoria Violet Hall and her children were living in Havelock, Ontario, with Mrs. C.A. Pounder. Hall embarked for France on 21 July and disembarked in France two days later.

“Shelling terrific … enemy snipers”

The sights and sounds of battle were everywhere and the first casualties soon after (25 July). The movement through Caen on the 28th brought scenes of “rubble and the destruction”, “the stench,” the “obliteration,” and jeeps full of the wounded and the dead. By the first days of August, many Argylls professed to “feel like a veteran now … having been shelled, mortared … and sniped at.” The town of Bourguébus was a “complete shambles.” The Argylls set up a command post in a dugout there on the 2nd August with the rifle companies taking “up positions on the perimeter.” A and B Coys “were forward.” It was “hot, dry” and “dusty,” with vehicles kicking up more dust and drawing fire, “heavy fire.” CSM George Mitchell, C Coy, wrote in his diary that day: “Shelling terrific,” “enemy snipers … Shelling still terrific – difficult to move around.” Pte Pinky Craig of the AT Platoon remembered: “you couldn’t move. Every time you moved, there was a rifle shot at you … It was a terrible place.” The Argylls had 4 KIAs that day, including Pte James Bannatyne, and 13 wounded; Joe Hall was one of them. August 2 was the first day of heavy casualties for the Argylls; it would not be the last. Although a newspaper report described Hall as “slightly injured,” he was hospitalized the next day and not discharged until 24 August, when he returned to the battalion.

“accurate mortar fire … immediately to their front caused casualties”

Hall’s return, presumably to A Coy, was in time for the fighting at Igoville, where Pte Joe Bearss was killed, and Hill 95 in late August, followed by the battles in Belgium and the Netherlands in early to mid-September. He was there for the comparative lull until mid-October, when Ptes Alexander Nickoloff, Douglas Marr, and Bill Patrick were killed, and the resumption of “nightmarish” fighting towards Wouwse Plantage, Essen, and the drive to Bergen-op-Zoom. LCpl Norman James and Pte Bill Du Trizac were killed on the 23rd and 24th. The 26th started inauspiciously with the departure of the Argylls’ great leader, Lt-Col Dave Stewart, for an operation. The detested 2ic, Maj Bill Stockloser, assumed command. A and B Coys were tasked to advance through the woods and to cross the anti-tank ditch “frontally.” The woods would be “booby-trapped and mined,” and there were concentrations of enemy mortars behind the ditch. The companies moved off about noon: they “found the going extremely tough and progress was slow: booby traps impeded their progress and accurate mortar fire … immediately to their front caused casualties.” They reached the ditch by nightfall. Pte Hall was killed in action and five Argylls were wounded. The precise nature of his fatal wounds or the timing is not known. The next day the companies moved northward.

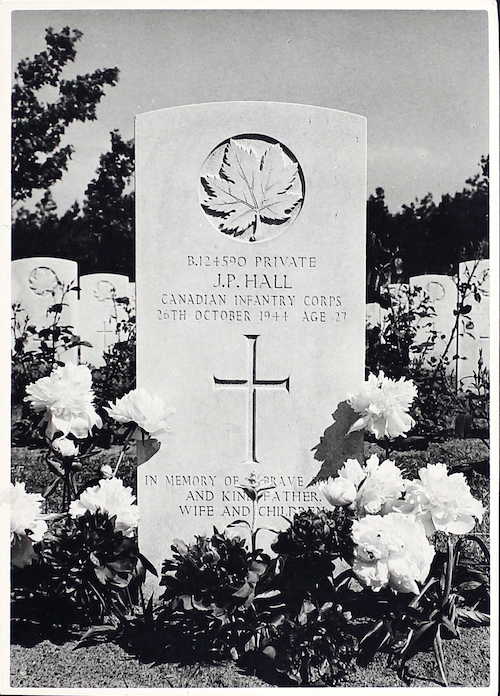

Joe Hall’s war was over and the unit, and his comrades, moved on. Now, he joined “the dead … a shadowy company that grew in numbers each day,” as Capt Claude Bissell expressed it. He was buried at Huijbergen, southwest of the church on the road leading to Bergen-op-Zoom by HCapt A.E. Butler, the Roman Catholic padre. HCapt Charlie Maclean, the Argylls’ padre, saw to his personal effects, the requisite paperwork, and the letters to the next-of-kin.

“remarried”

Victoria Hall received the life-altering telegram and by early December Pte Joe Hall appeared in the list of deaths reported in newspapers. As of February 1946, she had moved back to Coniston and, presumably, their home. She had two young boys and the direction of her life was forever changed. In the manner of many Argyll widows faced by this awful reality, she “remarried”; by 6 November 1945, she appears in Hall’s personnel file as Mrs Victoria Violet Flaherty. Joe had left everything to her, including his meagre handful of personal effects, which included the usual bits of paraphernalia carried by rifleman: a tobacco pouch, a cigarette lighter, a wallet, a watch, souvenir coins, a pen knife, “snapshots,” a rosary (he was Roman Catholic), a religious medallion, and an Argyll Glengarry (he had been around long enough to have one). His home in Coniston was valued at $1,000; he had a life insurance plan with the International Nickel Company worth $500, one $50 Victory bond, and a small bank account. His name appears on Inco’s “Roll of Honor,” along with that of two other Argylls, ASgt Cecil James Fisher, MM, and Lt Emmett J. Dillon.

Pte Hall’s family remembers him. His nephew, Bob Hall, wrote: “We never knew our Uncle, but his sister, our Aunt Bertha, was so very proud of him.” For her husband’s gravestone at Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery, Victoria Hall choose the following:

IN MEMORY OF A BRAVE SOLDIER

AND KIND FATHER.

WIFE AND CHILDREN

“a history bought by blood”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

“Death in battle is different” – We shall remember him – The Argyll Regimental Foundation on behalf of the serving battalion and the Argyll Regimental family

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Pte Hall’s poppy will be placed in the virtual Argyll Field of Remembrance in the near future. The Argyll Regimental Foundation (ARF) commissioned Lorraine M. DeGroote to paint the Argyll Poppy (below) for the Field of Remembrance.

Romford Road, Coniston, circa 1940s, where Joseph Hall and his wife owned a home.

Romford Road, Coniston, circa 1940s, where Joseph Hall and his wife owned a home.

Coniston smelter.

Coniston smelter.

Our Lady of Mercy Roman Catholic Church, Coniston.

Our Lady of Mercy Roman Catholic Church, Coniston.

Our Lady of Mercy Roman Catholic School, 1925.

Our Lady of Mercy Roman Catholic School, 1925.

Class photograph, 1925, Our Lady of Mercy Roman Catholic School.

Class photograph, 1925, Our Lady of Mercy Roman Catholic School.

Caen, France, 1944.

Caen, France, 1944.

Tank recovery at Bourguébus, France, 1944.

Tank recovery at Bourguébus, France, 1944.

Dirt road to Bergen-op-Zoom, Netherlands.

Dirt road to Bergen-op-Zoom, Netherlands.

The destroyed church at Huijbergen, Netherlands, October 1944.

The destroyed church at Huijbergen, Netherlands, October 1944.

German 8 cm heavy mortar gun, model 34.

German 8 cm heavy mortar gun, model 34.

Grave marker, photograph taken circa 1947, Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery.

Grave marker, photograph taken circa 1947, Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery.