Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Introduction

Last year I wanted to bring some historical light to the fighting in April 1945. There were two lines to my thoughts and they were inter-related: casualties and reinforcements on the one hand, the fighting ability of the battalion on the other. The “flame” of the Argylls’ group solidarity took light, as Maj Hugh Maclean argued, at Hill 195 (see Lt Milt Boyd). It was the effort of a well-trained battalion of soldiers. The “originals,” aa Col Alan Earp has called them, hailed from the early days of mobilization in 1940 and 1941. The “old-timers,” again to use Earp’s word, came as reinforcements from July 1943 through the early fall months of 1943; a few came a little later. Some – the originals – had four years of training by the time they went into battle in August 1944; others – the old-timers – had as much as 18 months. Moreover, the training extended beyond the basic and advanced phases, well beyond. There was collective training at every level, from the section to the division. Range work was continuous and intensive throughout 1943 and 1944, as was conditioning. New weapons were introduced and incorporated into the battalion, and officers, NCOs, and troops took specialized training. Combined with the brilliant leadership of Lt-Col Dave Stewart, it was formidable. Hill 195 was an example at the battalion level of what historian LCol Brian Reid dubs the “warrior spirit.” He cites other instances, only a few, and all at small unit levels such as a section, a platoon, or a troop.

This year, I concentrated at the outset of November on the casualties sustained in the first six weeks or so of fighting. Maj R.D. “Pete” Mackenzie thought that the tactical brilliance displayed at Hill 195 would not have been possible later in the war. Simply put, the unit had lost too many – far too many – well-trained soldiers at every rank level and never regained the sort of proficiency that accompanied that state. The stark reality of combat in the Second World War is written in blood, and the shedding of blood in those early months of battle led to a reinforcement crisis in Canadian infantry battalions, including the Argylls.

From 26 July to 6 December 1944, the losses were: 151 killed in action (or died of wounds), 458 wounded, and 32 prisoners of war, for a total of 641 lost to the battalion, largely in three months (August, September, and October). The figure does not take into account those struck off strength because of sickness or accident. During the course of the war, the battalion’s wartime establishment was just over 800. The war diarists, and later Maj Maclean, routinely gave 400 as the unit’s fighting strength (or roughly the equivalent of the four rifle companies: A, B, C, and D). It was higher. Support Company comprised the Pioneer Platoon, the Mortar Platoon, the Anti-Tank Platoon, and the Carrier Platoon). The Scout Platoon was attached to battalion headquarters and under the direct command of the CO. There were casualties within Support but it was a “bubble,” as Col Earp has described it, not decimated by relentless casualty reports. Of the 151 killed, 36 were original Argylls (from mobilization in 1940). After the actions of B and C companies at St-Lambert from 18 to 21 August, LCol Stewart had to amalgamate the two companies into one and, at that, their combined strength was barely more than 70! The casualties suffered after that date at Igoville, Hill 95, Moerbrugge, and Moerkerke exacerbated a grim situation.

“much needed”

The first reinforcements arrived on 4 September and the number was “sufficient” to revert to four rifle companies rather than three. The 81 reinforcements who appeared on 12 September were “much needed.” Pte Sam Resnick, a reinforcement, remembered “going up [to the Argylls] … after some minimal training.” Pte John “Mac” Mackenzie, helping with the wounded on that day, recalled one of the new drafts taking in the sight of the wounded and saying, “Boy, it’s tough out there.” Mac replied, “No, it’s not a bad day,” and the young man “went green.” When new reinforcements arrived on 6 October, Cpl Harry Ruch recorded in his diary that he and others were going back to A Echelon (in the rear) “to train” them.

Training was the key, not only for the fighting proficiency of the battalion, but also for the survival of the reinforcements. Maj Bob Paterson, OC of C Company, struggled to lead a company short of officers, NCOs, and men. Lt Harold Place, B Coy, said, “It was nothing to go out with a platoon of maybe eight people – which is crazy. Where were the reinforcements? I don’t know.”

“they were just hopeless”

Maj Paterson had “no faith in the reinforcements and that’s what I ended up with practically a company of reinforcements, and they were just hopeless … You’d try and train them, [but] we didn’t have any time.” A/Cpl Burt Eden, B Coy, thought “it always seemed us older guys seemed to get through and the reinforcements didn’t … [they] didn’t have the real training, like. Or maybe it was just their time, I don’t know. But it takes a long time to get to know when you move and when you don’t move and when to put your head up, when not to. Takes a while.”

“exposure to battle … the hardest adjustment”

On 4 November, 20 reinforcements arrived, all Argylls who had been wounded in France, had healed, and were now rejoining the unit. They were not a problem. Three days later, the unit received 10 officers and 120 ORs (other ranks), a huge infusion. Happily, there was little action in November and December. It provided the battalion with time for training and integration at the section and platoon level. Maj Pete MacKenzie thought the latest tranche were “fairly well trained” except for “exposure to battle … the hardest adjustment.” CSM Wilf Stone, A Company, thought “they [the reinforcements] were the guys that go through the fastest.” MacKenzie’s faith rested with the cadres of experienced NCOs and soldiers to provide the essential leadership to new Argylls and to integrate them. Lt Place, for his part, talked about the platoon and then introduced them to the sergeant or corporal “if he had one.”

There had been a relative lull in the fighting since 19 September; it began again on 15 October. Ptes Gordon Douglas Marr, Muir J. Marlatt, and William Patrick all joined the Argylls on 12 September as part of the “much needed” tranche of 81; Pte Alexander Nickoloff joined on 28 September. It proved a fateful time for them to become Argylls. All were recent reinforcements; all were killed on 15 October 1944. The previous day Pte Jack Robert Reibeling, an NRMA enlistee, was killed in action; he had joined the Argylls on 23 September.

There were legitimate concerns about the timeliness of reinforcements, their state of training when they reached the unit, and the amount of time both to integrate them into their platoon and company and provide further training. The reinforcements arriving in September and October, if they survived, received that last component during the lull in fighting from early November until mid-January. Reinforcements such as Pte Colin MacLennan and ALSgt John Glavin had become, by the time of their deaths in April 1945, old-timers now taking their place as part of the cadres at all rank levels holding together and sustaining the battalion in battle.

The renewal of fighting in January 1945 at Kapelsche Veer (see Pte Donald MacKeracher) and the Hochwald Gap in late February (see LCpl Fred Woodward Jr) entailed more casualties and in large numbers. Yet again, there were more reinforcements especially in late February and early March, soldiers such as Ptes Ernest Madaire, Edward Smith, and Clarence Vaise, all of whom were killed at Veen, Germany, on 7 March. Madaire’s sad saga is a tale of a reinforcement arriving at a time of heavy losses and considerable confusion; he had but days to integrate and it was not long enough. Others arrived in those days after the Gap and before Veen; Pte Carl Donnelly was one of them. He was, at least in terms of the record in his personnel file, better trained than the reinforcements of September and October had been. He was thrown into Veen, his platoon – 12 Platoon, B Company – got lost in the dark and he avoided the deadly fate of others in his company. Unfortunately, his luck did not last out the final weeks of the war.

When I reviewed the casualties of 24 April, I reacquainted myself with Pte Donnelly’s name. I first learned of him during the interview of then Col Don Pruner. Not only had Don served in the same platoon as Carl Donnelly, but he was with him when he was wounded (Don was wounded as well).

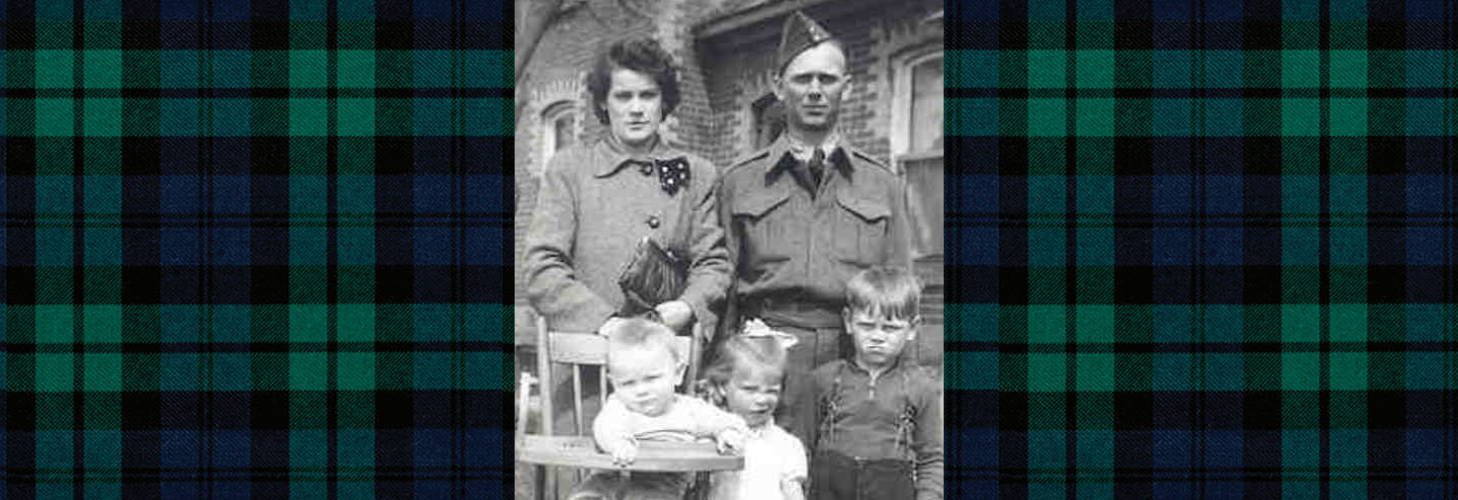

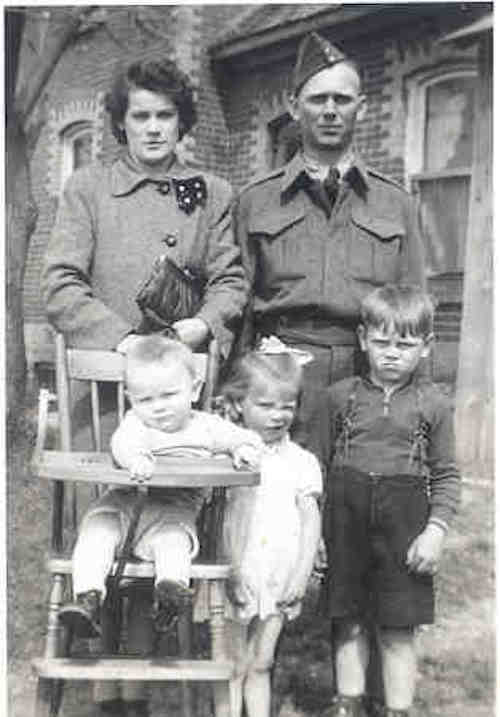

I am grateful to Gary Donnelly, Carl’s oldest son, for providing me with Carl’s surviving letters (he tried to write daily), a candid interview, and images of Carl Donnelly, Hilda Donnelly, and their children. I also thank my son, LCol Rob Fraser, CD, and his wife, Jerica, for picking up the package from Gary.

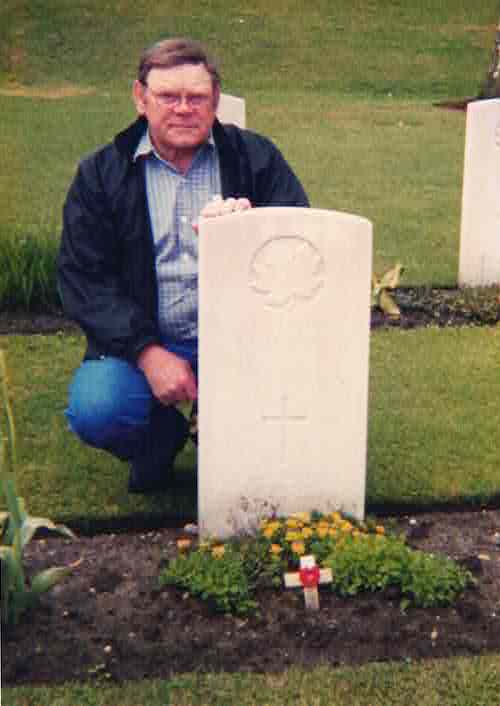

As I wrote this piece for Pte Donnelly and his family, I was constantly reminded – as I often am – of the remark by Professor David R. Winter, Brandon University. He is the grandson of LCpl Frederick Woodward Jr, whose biography appeared last year (there is a picture of a rather young Professor Winter with his grandfather’s biography). David wrote me: “It is so very poignant when the scale of the war is reduced to the level of a single soldier.”

Then, when I finished, I thought of Lt Alan Earp’s comment last year about Capt Jack Prugh and his family:

Alas, I never met Jack Prugh, although I had heard well of him. Thanks to the material you have put together I know him better now. Virgil summed it up in six almost untranslatable words: ‘sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt’. (The best I can do is a prosaic ‘Tears well up as the human condition touches the heart’.)

Indeed!

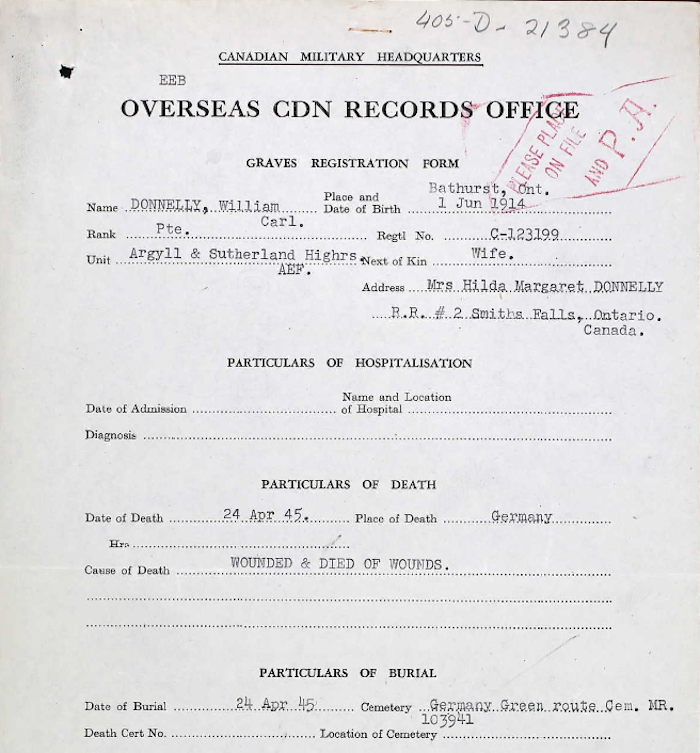

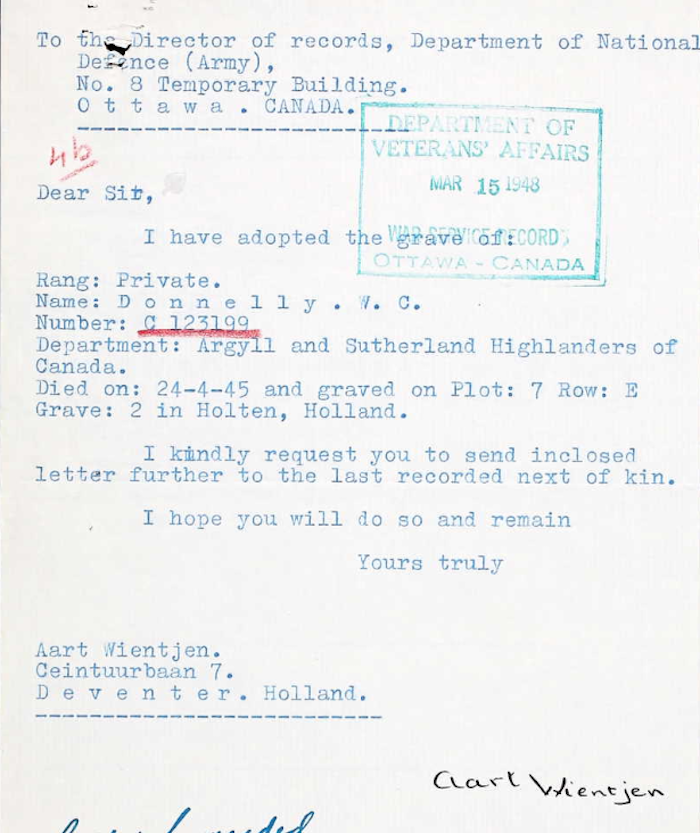

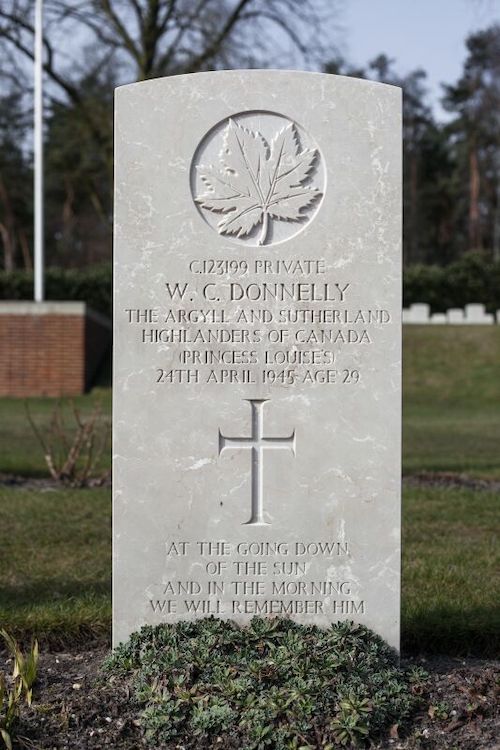

Pte William Carl Donnelly (1914–45) (C 123199)

DW 24 April 1945

“section man”

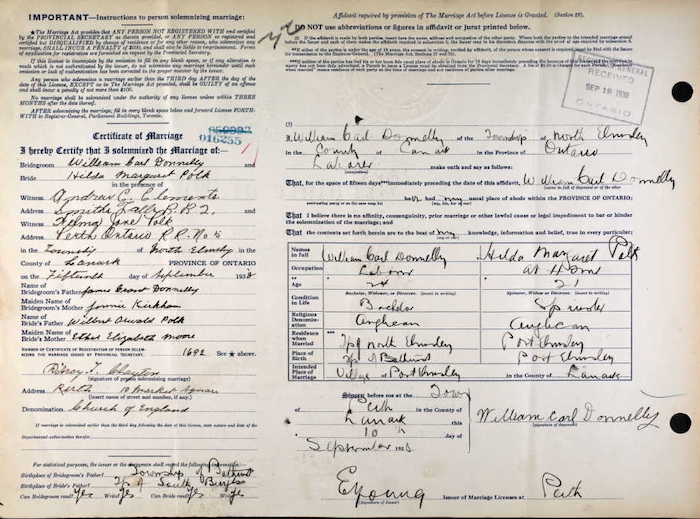

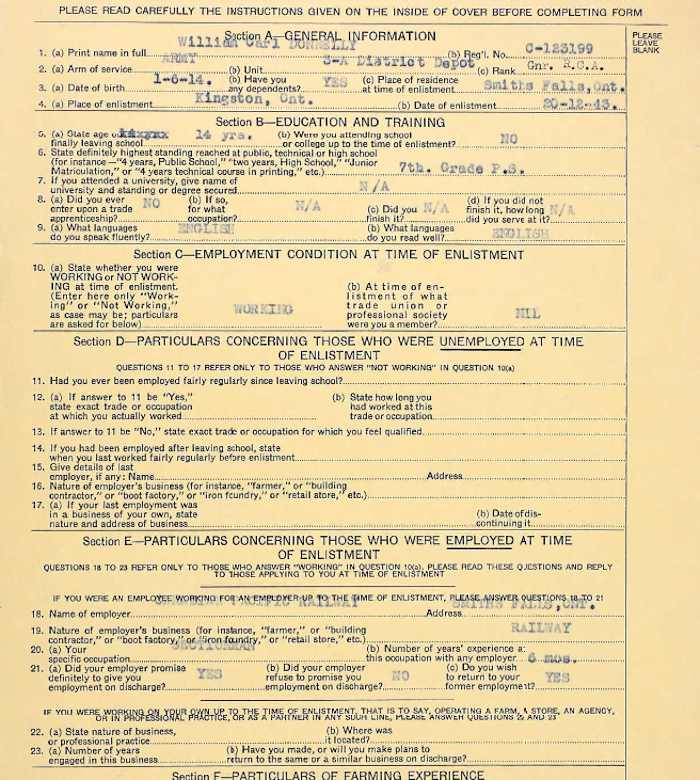

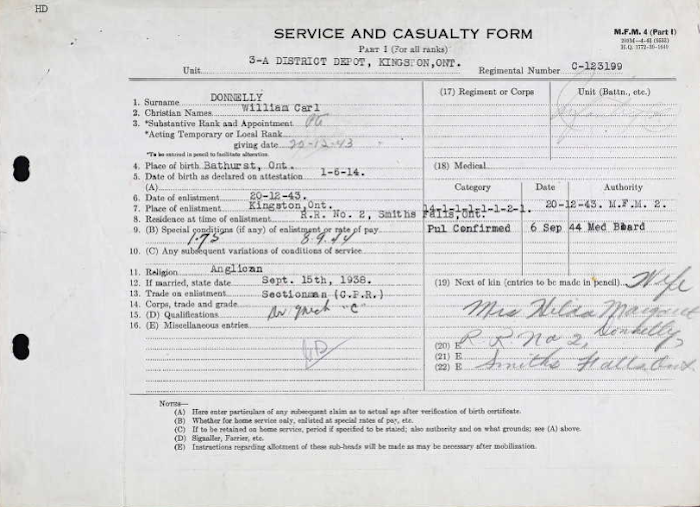

William Carl Donnelly was born on 1 June 1914 at Maberly, Ontario, to James Grant Donnelly (1891–1970), a section foreman on the Canadian Pacific Railway, and Jane “Jennie” Kirkham (1887–1980); they had married at Maberly on 11 May 1909. He had three brothers and one sister. Carl (he signed all of his letters “Carl”) was a “section man” on the CPR and had completed grade 7 when he left school at age 14. When he enlisted, he had one year of farming experience, felt competent to run a farm, but had no desire to do so after the war. The CPR promised to rehire him upon discharge and that accorded with his wish. He married Hilda Margaret Polk (1916–2002) on 15 September 1938 at St James Anglican Church in Port Elmsley, Ontario. They had three children: Garfield Russell Grant Donnelly, Phyllis Elizabeth Jean Donnelly, and Robert Carl Wilbert Donnelly.

Marriage certificate, Hilda Polk and Carl Donnelly.

“Very quiet personality, deep thinker, actions very deliberate”

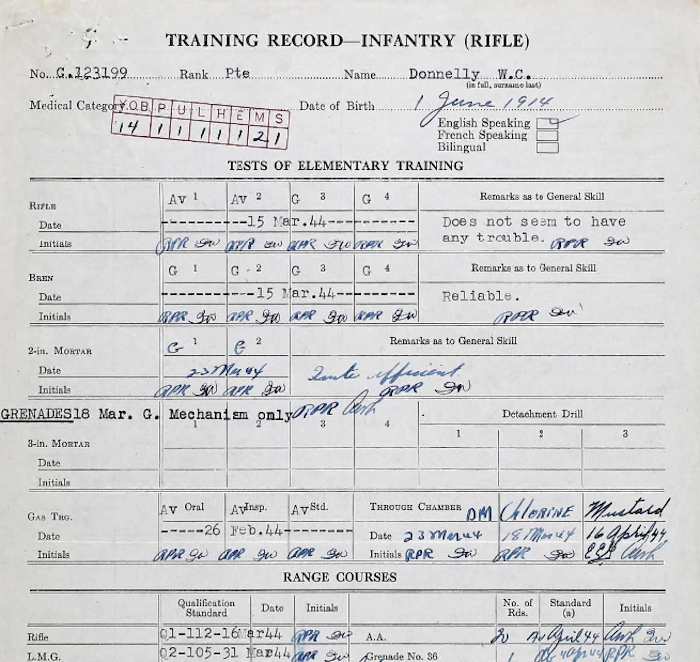

He enlisted at Kingston, Ontario, on 20 December 1943 at No. 3-A District Depot. He was 5’, 5½”, 135 lbs, with blue eyes and brown hair. He was taken on strength on 31 December at No. 31 Basic Training Centre in Cornwall, Ontario, where he underwent basic training. He had a good record in basic training. On the rifle, he was “slow”; on the light machine gun – “very deliberate, gas – good”; first aid – “slow, map reading – “Good worker”; fieldcraft – “good worker”; fundamental training – “Fair knowledge”; and his standard – “good shot.” Overall, on most subjects that ranged from drill to field training, mines and booby traps, he was “average.” The common phrases were “good worker” who “tries hard” with a “fair knowledge” and, at times, slow. His company commander remarked:

Very quiet personality, deep thinker, actions very deliberate. Works hard – studies, very methodical. This man has had extra periods in Small Arms, Gas, Map reading, Rec AFV/AC, Grenades, & Fieldcraft.

“Satisfactory soldier”

Upon completion, he was transferred to A-29 Canadian Infantry Training Centre (CITC) at Camp Ipperwash on 26 February 1944. There were a range of general remarks upon the completion of advanced training. Common training had 16 separate subjects covering fundamentals, four types of weapon, drill, physical training, marching, field training, night training, and others. In terms of physical training, Donnelly “Does his best to succeed”; in marching – “Endurance good”; in map reading – “keen and interested”; on PIAT – “Knows weapon”; on cooking in the field – “Uses initiative” (a life skill for a soldier); on some subjects, there were familiar refrains: “tries hard,” “slow,” and “interested.” The concluding comment: “Satisfactory soldier but no world beater.”

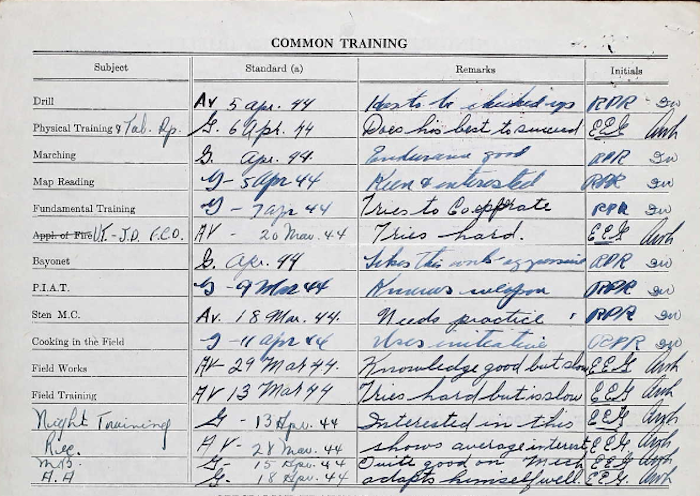

On 5 May, he was attached to S-5 CD & MS [Canadian Driving and Maintenance School], Woodstock, Ontario, for the “Driver I.C. Course.” On 16 June he was attached to S-9 CD & MS. He qualified as driver “IC class 111” on 10 August 1944 and was granted 14 days embarkation leave to 27 August.

On 8 September, he received “trades pay Dvr Mech Group ‘C’” and was reclassified as “Dvr Mech MV [Motor Vehicle].” On 14 September 1944 he was taken on strength at Debert, Nova Scotia, to await embarkation for overseas. He left on the 14th, arrived on the 20th, and reported for duty at #4 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU) on 21 September.

“here I am a long way from home”

Once overseas, Carl Donnelly wrote home daily, usually “before supper” when he had a bit of time. There was a ritual quality to it, evident in his use of standard openings and salutations; it was a time within his busy days given over to his wife, Hilda, and their three children: Gary, Phyllis, and Bob. His letter of 21 September [note: this letter has 21 October written on it in different handwriting; both the content and the faded postal mark suggest it was 21 September] found him:

here I am a long way from home … But have not yet rested up from my trip. But I know it must have been a long hard worry for you at home with no word from me. But I was think of you and the children most all the time and I am praying for the day I can go back home. We had a good trip over. But I was kind of sick for a couple of days … How are our three grand children feeling and also very body around the village … I was pretty lonesome body when I saw the shore of Canada faid out of sight. But you still have my love lock up in your heart so take good care of it (Ha) (Ha) which I know you will … But do go out and try and forget some of your worry about me.

“Every time I see little Kiddes it makes my heart ache”

He asked her to “send me some smokes. That is all that I will need…. Every time I see little Kiddes it makes my heart ache. I can hardly believe that I am so far away from home. “

“So by by for now with all my love to you as always your Carl”

Pte Donnelly’s letter from 4 October 1944 has his usual opening – “My Dear Hilda + Kiddes” and then a line repeated, almost word for word, in every subsequent letter: “Well here I am again this evening with a few more lines and hoping it will find you all well as it leaves me pretty good[.]” The sentence conveys hope about his family and reassurance about him. Donnelly wrote Hilda “seven letter every week.” They dwell on everyday matters such as whether it was faster to use air mail or not, what the children were doing, how they were faring, their families, and life in the village. It gratified him to receive her letters and parcels and to learn she had been “dreaming about before we were married.” Although he relished the parcels and their contents, he worried endlessly about “spending your money on me.” He outdid himself and most Argyll letter writers in his closings: “So by by for now with all my love to you as always your Carl” followed by 34 Xs and Os.

“received your most welcome letter”

He wrote again on the 5th, having “just got in from work and have been out all day.” He started the letter “early as this is work night and I don’t want to miss write you a few lines.” “How are the Kiddes feeling I would love to see the young monkey [Bob]. Well it will be three week tomorrow since I landed here.” He then paused for a bit because mail had arrived – always a treasured moment – and then picked up again. He had “received your most welcome letter and was glad to know that it left you all fine at home…. So Bob is my boy. I suppose if I don’t soon get back home he will not know me [Bob was the youngest].”

“you are the only girl I ever wanted”

On 10 November 1944, Carl was “glad to hear the Kiddes had a good time on Halloween night …” He noted that Gary “is a pretty good little man” and “Bob is starting to say some words now. Say is Phyllis growing any more she sure is a small in [?] girl. But sure has lot of life (Ha Ha).” Apparently, in a recent letter, Hilda told Carl she was “dreaming of me having another Girl out [.]” He replied emphatically, “well don’t worry about that for you are the only girl I ever wanted.”

“But it us Boy[s] that has to pay for other people freedom”

Carl Donnelly rarely made reference to where he was or what he was doing. The few instances provide a glimpse into his thoughts about the war:

But it is very sad about Lorne Covell [Pte Lorne Hubert Covell, KIA 14 October 1944 in Italy]. But it us Boy[s] that has to pay for other people freedom yes it is to[o] bad that they do not send the zombies over as we sure need them to help us out. But I sure hope you and my boys never have to come into the army know [sic] boy no what kind of a life only the one that have to stay and live in it. For we can and will pay the full price for the freedom that come after. But we will not all see it. It is hard to write with some of the frencemen [sic] trying to sing.”

“for some chips + bacon and cup of tea (Ha Ha)”

He was over to the NAAFI [Navy, Army, Air Force Institute] canteen “for some chips + bacon and cup of tea (Ha Ha). But a hot cup of tea goes pretty good for that is all I drink now.” He hoped to go “to a show to morrow night.” He had seen three shows the past week:

But must sooner be going to see you Hilda. For it is hard trying to live away from you. But if I can get home again we will make it up wont we darling.

He added a row of Xs across the page with a row of Os underneath: “I would like to be giving you some Real kisses & hugs.”

“I am now somewhere in Belgium”

Pte Donnelly was struck off strength to the X-4 list [unposted reinforcements] on 23 November 1944, embarking the same day for northwest Europe and arriving there the next. He was taken on strength at No.2 Canadian Base Reinforcement Group [CBRG]. Three days later he wrote to Hilda:

nice bright day here But I am still far away from home than the last letter I wrote to you. I am now somewhere in Belgium and had a good trip over here.

“Well it soon [will] be Christmas time”

He asked about the kids wondering if:

“they are starting to think about santa claus coming. Well it soon be Christmas time But I guess it wont matter much to me this year. I am in with all Ontario lad[s] but they are from perth, smith Falls, Brockville and Ottawa and one from Crowlake so it makes it nice … It is fun to see some of the people wearing wooden shoe around here. But this is nice country around here.

Mail was, to be clichéd, a lifeline between a soldier and his family. The move from England interrupted the once regular flow of mail and it bothered Carl. On 13 December, a Sunday, he advised Hilda that “I have not received any mail since I left England.” He had met a few soldiers from Smith Falls, one of whom recognized him on parade, and the previous night, he saw “a pretty good show and [it] was free to soldiers.” He imagined that the store windows in Perth and Smiths Falls would be “starting to look pretty nice” in readiness for Christmas. The second conscription crisis was in the news and it spurred him to make one of his rare political or military comments: “I hear that the zombies are coming over here. They wont like that very well.”

“sure hoping to be home next year with you”

On 17 December 1944, Carl bemoaned the fact that mail delivery remained slow. He reminded her that “Well Darling it is a year since I Joint the army now a long year too. But sure hoping to be home next year with you wouldn’t that be great.” At most times, pay day was never far from a soldier’s mind and it was true for Pte Donnelly. He thought:

to morrow is pay day for us. But money goes fast here as things are so dear. But I do not gout very much. Just saving up my good time on till I get back home and we can enjoy ourself together.

Christmas overseas was especially hard and he wondered how “the Kiddes getting alone with the piece they are going say at the school for christmas. … “Well, by, by, my sweet loving wife and children.”

“Did you get yourself a winter coat yet[?]”

As Christmas got closer, Carl was desperate for news from home. On 19 December he moaned:

I still have not received any mail as yet … How are the children I can Just see them waiting for christmas morning to coming. Do you remem[ber] the christmas that Gary got his wagon. How is your wood + coal hanging out have you got enough to do all winter. I hope you have. Did you get yourself a winter coat yet[?] …

“I can[’]t get you out of my mind”

He asked about Hilda’s brother, Russell Polk, who was serving in Italy before returning to his constant concerns about his wife:

I suppose you have not got a radio yet I hope you can get one this winter. If you think that you can handle it buy a new one for I sure don’t care. For anything to make you as happy as possible. But I know that we cant be very happy when we are apart. But the day I get home again you and I will make up for the loneliness wont we darling … For I love you so darling I cant get you out of my mind. But I know that you are the same well by by my love …

“I am falling in love with you all over again. Hilda”

Carl Donnelly’s anxiety about his wife was a constant and a growing one without mail. He had “Just come from the canteen,” he wrote on 29 December 1944, “so I am eating a chocolate Bar.” He had yet to receive any mail and had written the night before, enclosing a handkerchief that cost him 40 francs:

But I do not mind spending my money on you dear For it is a pleasure doing it. I think Hilda that I am falling in love with you all over again. Hilda, I will not leave you along [alone] again like I use to. For I want you to be with me where every [ever] I go to work.

“nice to Know that I have somebody waiting for me at home”

He asked, as always, about the children hoping:

Gary does not cry any more for me … But keep your chin up darling and smile and with God help I will be able to come back again so we can be happy… But it sure feel nice to Know that I have somebody waiting for me at home it help[s] a lot Hilda.

It had been but four months, it seemed like a year: “by by Hilda the most sweet wife in the world…”

“when I get home I will Keep you warm (Ha Ha)”

The importance of mail was affirmed by Hilda’s brother, Trooper Russell Polk. He wrote to her on 1 January 1945: “I am receiving my mail quite regular of late, that is one thing to keep the moral[e] up, when mail time comes and no mail, you feel pretty low …” Happily for Pte Donnelly, mail caught up with him in the early days of January 1945, along with parcels. On the 4th, he thanked Hilda for the tea, candy, cookies, and “smokes.” He wished she had kept the tea for herself. He expressed, yet again, his concern about heat in the house. It was a common refrain as to whether there was enough coal and wood, whether Gary helped her bring it in, whether she should sleep on the first floor because the second was too cold, or if she needed a new winter coat. He was glad to learn that the house is warm, and it provided him a more personal perspective on human warmth: “But when I get home I will Keep you warm (Ha Ha) and take you to bed good and early if I can.” He mentioned “I was thinking of sending you some souvenirs But I think I will wait until after this is over” Two days later, he penned a short note about the kids and his longing to be with her: “I have just read all the letters I got from you over again. Will you send me a picture of yourself and one of the children some time If you can.”

“try and save all we can for after the war”

The letters become shorter in January and it is clear that Pte Donnelly is quite busy. Their brevity accentuates Carl’s increasing worry about Hilda, his desire to make her happy, his plans for their future, and his love for her. He found it “hard to believe,” he wrote on 28 January:

that our children almost grown up and ready for school. we are getting quite a bit of snow over here this winter. This is the most they have had for years. .. But we will have to try and save all we can for after the war as we will sure need it. But if nothing should happen to me I suppose to have about 130 dollar come …

“I love you so much darling”

He reiterated the now common themes on 6 February 1945 while waiting for mail, wondering about children, worrying about her:

… And how I wish I was close to you to night For I love you so much darling that it hurts to be so far away. But I know that you Know all about it. … I hope it is not so cold over there now But it will soon be spring again.

“But there is still many a hard day ahead yet”

A touch of fatalism crept into his letter of 12 February. There was no recent mail, the assault on Germany was imminent although he does not mention it, and he was closer than ever to the battlefield:

For it is you who needs the mail worse than I For it is you at home who has all the worry and suffering. Not Knowing where I am … But maybe before to[o] long we will be able to go back home. But there is still many a hard day ahead yet.

He asked about the kids and, once again, urged her to buy a radio, even a “small radio” for “some comfort at home.” Hilda, for her part, resisted his entreaties, steadfastly saving every spare dollar for their future.

The Argylls took him on strength on 28 February 1945 and posted him to A Company; on 1 March he was posted to B Company. It was a precarious time for the Argylls, especially B Company.

“the majority of them to B Company”

The Argylls and B Company in particular sustained heavy casualties in the battle for the Hochwald Gap (see LCpl Fred Woodward and Lt Hugh John McCutcheon).The war diarist noted on the 1st:

At 2100 hours thirty-two reinforcements arrived and were allotted to the rifle companies, the majority of them to B Company. The weather turned substantially colder at night; visibility was good. A few enemy planes were active behind our positions, attacking searchlight batteries and drawing a substantial amount of Ack Ack fire.

Pte Donnelly arrived at night – the unit was stationed “east of Udem” – and, as for the day itself, Capt Sam Chapman, D Company told his wife:

Lord but the weather is miserable to-day – a bit of a wind and a cold driving rain – not actually awfully heavy but adds up to mud and wet clothes after a few hours…

“This thing cannot be done at no cost”

Chapman had acquired a soldier’s fatalism about the reality of battle and its cost. He tried to persuade Mardy Chapman that she should go on, come what may:

Gosh I hope you’re not doing too much worrying – there’s no sense in that. This thing cannot be done at no cost – and everyone of the fellows who goes in has his own private life which is just as important as anyone else’s. So keep your own chin up and have a faith and if necessary a philosophy and you’ll be all right [sic]. You’ve a long lot of years to live yet and you deserve to be happy…

Pte Donnelly would have agreed, he had warned his wife that there would be “hard days ahead.”

“practically all new, like we’d all come up together, a bunch of reinforcements”

Pte Don Pruner, a volunteer, was one of the 54 reinforcements that arrived on 1 and 2 March. He was posted to 12 Platoon, B Company, the same platoon as Carl Donnelly. Pruner provides a sense of the tone of their welcome and its location:

I think I had a good command of the weapons that I was expected to use. Basically I thought I was reasonably well trained.

…we actually joined B Company … around a farm house … I do recall this rifle I had being zeroed for me in Canada and which I’d been told was my best friend. And I had it zeroed again in England, and I just sort of carried it and loved it as my brother and so on. And they said, “Okay, Pruner, you’re going to be in the Bren group, and we don’t need two rifles, you need one rifle and one Bren gun, and you’re going to carry the gun, so give me your rifle.” And they sort of threw it over in the corner of this barn. And so I remember sort of thinking that was funny after, you now, my rifle had been zeroed for me as my own personal friend and now it was gone.

But then I remember [A/Major] Len Perry [OC, B Coy] came out … he was sort of fierce looking. I saw him, he had this black moustache. And very intense, and sort of almost on a high … in terms of his enthusiasm and all that … and he was telling us about some lieutenant [Lt Hugh McCutcheon] who he had had a lot of respect for and he’d just been killed … But anyway, he sort of welcomed us to the Company as it were, and I guess what he was trying to do was … give us a little backbone and a little … regimental inspiration and so on.

…The platoon that I was in, we were practically all new, like we’d all come up together, a bunch of reinforcements … There was a corporal, I remember, named [K.A.] McLaughlin. The Sergeant’s name was [J.W.] Boudreau. He came from Nova Scotia … part Indian, a short man, tough as nails … He wasn’t exactly your image of a Highlander, but he was a very tough guy who’d probably had a hard life … But he had a lot of natural … leadership in him.

In spite of B’s battering in the Hochwald Gap and large losses, the platoon sergeant, Boudreau, was, by this juncture, an old-timer as was the corporal. Donnelly, like Pruner, had been welcomed to the Argylls and found not only an immediate family but also experienced leaders. The two reinforcements missed the battle in the Gap and would have a few brief days before experiencing the next onslaught.

“this debâcle – the second for B Company within one week”

On 3 March, the weather was milder and the day uneventful. Two days later, the battalion moved into the woods near Sonsbeck for the anticipated attack on Veen. As the unit waited, it poured rain. The attack on the 6th faltered. That night, brigade headquarters ordered Lt-Col Fred Wigle to take the town by daybreak. He decided on a two-company, night-time infiltration under a creeping artillery barrage. B and D companies would attack after midnight on the 6th. The war diarist wrote a sobering account of the two-company ordeal:

After this debâcle – the second for B Company within one week – B and D Coys were formed into one company under Capt SDG Chapman. B D and C Coys firmed up well clear of the town, along the main road. Throughout the night there was repeated and concentrated enemy shelling and mortaring, causing casualties among our troops.

“One platoon from ‘B’ Coy got completely lost”

Wigle reported:

One platoon from “B” Coy got completely lost finishing as far East as the crossroads … and finally returned intact to Tac [Tactical] HQ … It subsequently turned out that “B” Coy, who were to clear the Southeastern portion of VEEN, had come under heavy machine gun fire from that sector and had changed their axis of advance moving North … “D” Coy confirmed the advance of “B” Coy and was approximately 100 yards to the rear.

“we were just going to drive up into Veen and then occupy it”

It was the first battle for the reinforcements of 1 and 2 March. Capt Len Perry, the OC for B Company, was probably suffering from battle fatigue given his company’s tribulations in the Hochwald Gap, the death of Lt McCutcheon, and the company’s considerable casualties. Pte Pruner:

…all I really recall is this sort of briefing we had … I think it was somebody in the Intelligence Section … My recollection of the briefing was that this was going to be … almost a formality. We were closing up to the Rhine, the Germans had more or less accepted the fact that they’d lost that side of the Rhine, and we were just going to drive up into Veen and then occupy it.

“a good idea, perhaps, under troops that were used to doing it constantly”

That assessment occurred prior to the stalled attack on the 6th. In the early hours of the 7th, as Lt Herb Maxwell of B Company (10 or 11 Platoon) recalled:

…We went in under a lifting barrage … [The] lifting barrage would have been a good idea, perhaps, under troops that were used to doing it constantly.

“I recall the mortars dropping in front and closer, closer and then behind”

For Pruner, and presumably Donnelly, in 12 Platoon:

…I recall the mortars dropping in front and closer, closer and then behind, and … a lot of fire coming over our heads from our own artillery … I suppose I was nervous … I was probably scared. You know, if you wouldn’t be scared, you’d be a fool. But I don’t recall being as frightened as perhaps I was later on…

It was a dark night and 12 Platoon got lost. Communications between the companies and the battalion, between the companies, and among the platoons of each company broke down when B Company’s 18-set (man-packed high frequency wireless set) malfunctioned – a not uncommon occurrence. Runners got lost. In the end, although Wigle had recalled the companies, only D Company commanded by Capt Chapman fell back. Perry put in a two-platoon attack on a heavily fortified position and it failed badly.

Fifty-one Argylls were killed, wounded, and/or captured. Of that number, only 2 had been with the unit before 9 September 1944; 17 joined as reinforcements between 9 September and 29 November; and 32 were taken on strength between 9 January and 7 March (most arrived in February, many in late February/early March). Some like Ptes Ernest Madaire, Edward Smith, and Clarence Vaise were recent reinforcements. Their situations, as recent reinforcement, were by no means unique; 24 of them joined the unit between 28 February and 7 March. Of the 51 total casualties, 22 were from B Coy; 21 from D; and 8 from other companies; plus 6 from C Coy and 2 from Support.

“you could hear the shooting and everything else”

Donnelly and the rest of 12 Platoon were spared that fate because they were lost. “As I recall,” Pruner said:

… the platoon I was in was sort of the reserve platoon … it seemed to me Len Perry and Company Headquarters were ahead of us … we were kind of in extended line formation … and off we went … it was very dark … within a couple of hundred yards you could see the outline of trees … with a farm house or something like that. I’ve often wondered how the hell did we get lost, you know, because we were like an extended line. We weren’t going along single file and following one guy who got lost. How could a group spread out like that get separated from the [two] platoons in front?

Eventually I knew we were lost because we came back to … where we started out from, and it was then … common talk that we’d gone astray and you could hear the fight, you could hear the shooting and everything else … To this day [Pruner ended his military career a full colonel] I don’t understand how a platoon in extended line formation could get that far off track and not make it there. I don’t know. To this day I don’t understand that.

“all of a sudden things opened up in the direction we were going”

Pte Earl Stillman of 12 Platoon had a similar recollection:

…we were supposed to put in this attack early in the morning, and reconnaissance had gone ahead and spotted it all out and said everything – bridges and everything – were intact and everything. So when it come time to move, why we started advancing down through the ravines in one spot. And when we got to the edge of the town, why we just go … a little piece and we’d stop. And I guess the ones up ahead would kind of scout it out a bit … and see what happened. And then they passed the word back down the line to advance, and we were going along fine. And then all of a sudden, we come to the conclusion that we haven’t been moving for a long while. And the third fellow up ahead of me, he had nobody ahead of him. And he didn’t know whether he hadn’t heard the chap or that the other fellow hadn’t passed the word on.

Then all of a sudden things opened up in the direction we were going. And we knew there was no use of us trying to get up in there because we didn’t know exactly where they were. So we decided we’d better retreat, so we headed back the same way we were going. And the Germans, you could hear them from the buildings, whistling at us … so we got quite mum until we got back…

“a helluva mess going on up there and you could hear all this firing and everything”

12 Platoon went into a barn. According to Pruner:

…we were told just go in the barn there and get some rest, and wait further instructions, and that’s when [Sgt J.W.] Boudreau came out and got me and a couple of other soldiers and told me to take them up the road and find out what was going on and report back … still dark … there was talk then that there was a helluva mess going on up there and you could hear all this firing and everything.

…we got about three or four or five hundred yards up the road and a couple of guys came running down the road – crying. Like there were really frightened. They were running in fear … very, very frightened, and they were crying and you know, really like broken guys. So we got hold of them and we decided that they probably knew as much about what was going on up there as we could find out by stumbling up in the dark, so we took them back, and they handed them over to the NCOs and I guess they took them for debriefing with Intelligence people … I just went back to the barn and went back to sleep.

“total casualties were close to 300, or almost 75% of … total fighting strength”

On 9 March the war diarist took stock:

The Battalion had suffered approximately 260 killed and wounded in the 12 days of action since leaving Cleve. With battle-exhaustion cases – of which we had several during the Hochwald ordeal – and sickness cases added, our total casualties were close to 300, or almost 75% of the Battalion’s total fighting strength. Throughout the fighting we had received a constant flow of reinforcements: but these reinforcements still required several weeks training to properly adjust themselves to the Battalion.

“laying out in the field, dead, where they had been killed”

Donnelly, Pruner, and the rest of the reinforcements in 12 Platoon had missed their first battle. They had, however, brushed up against it: the noise, the confusion, the darkness, the unknown, the shooting, and the fear. They bore witness to its tragic results when the battalion went into Veen on 9 March. For Pruner, it meant realizing his mortality:

…when we eventually went into Veen … we just like marched up the road in full daylight. And I could see soldiers, I could see bodies laying out in the field, our Canadian soldiers laying out in the field, dead, where they had been killed during the attack. Well, I recall seeing what happens to a soldier when he gets hit in the head. The body seems to freeze in the position that it’s in at the moment of death … So that was something almost of academic interest, but it did have an effect of, you know, when you see a whole section of infantry lying out there dead, just where they’d been shot when they’re advancing across a field, it does give you some thought that you’re mortal, you know.

“entire day was devoted to a general clean-up for all troops”

The next day – the 10th – the battalion was in Veen. A casual observer might have thought what a difference a couple of days makes an active theatre of operations:

…The entire day was devoted to a general clean-up for all troops. A Sally Anne canteen and movie was set up in Veen. The feature presentation was “Madame Curie” … Up to the present time we had received no definite word as to the length of our stay in Holland, but we hoped it would enable us to properly prepare our Battalion for the next task – the Battle of Germany East of the Rhine.

“It has been quite a shaky business at times”

The 10th gave Capt Sam Chapman pause to reflect on Veen in a letter to his wife:

…It has been quite a shaky business at times – once especially I was quite sure I’d lost the whole coy [on the night of 6-7 March] – Infiltrating with a whole coy is quite a proposition – especially when you find you’re infiltrating into something at least 20 times as strong as the information given. But such is war…

“being pulled out of the line for a period of two to three weeks”

On 11 March, Maj-Gen Chris Vokes, the general officer commanding the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, met with the senior officers of the battalion at its tactical headquarters in Veen. “He informed us that the entire Division was being pulled out of the line for a period of two to three weeks, for thorough training, re-organization and re-equipping.” For his part, Lt Alan Earp, the Pioneer Platoon, was pensive and expressed his thoughts to his parents:

…Now another battle is over and I’m still going strong but there are a lot who’ve fallen by the way. It’s been very grim but I’ve been spared the worst of it. The next fight will be across the Rhine and it can’t be any tougher than this. I’m sick & tired of all this mess and of having to be so beastly.

“miles from … enemy shells or mortars”

The battalion reached Esch, a small town northwest of Boxtell, in the Netherlands at 0730 hours on the 13th.

Billets had been arranged for the entire Battalion in this friendlier-than-average Dutch community, and general morale was very high since we were many, many miles from the all-too-familiar whistling, whining, cracking and crumping of enemy shells or mortars.

The entire day was given to a general clean-up and rest after our dusty night-trip. The weather, which was generally against us while operations were taking place, decided to favour us, and our first day at Esch was warm and spring-like.

“seemed like ‘Paradise Regained’. And so it was, for the winter turned to spring”

For Cpl John Booth, Anti-Tank Platoon, (Booth had joined the battalion at Niagara Camp in early July 1943):

Coming back to Holland, to people who would look you in the eye and smile, seemed like “Paradise Regained”. And so it was, for the winter turned to spring and the branches of the new budded trees lifted and sighed to an almost summer breeze and the sun shone all through the late March …

The pause at Esch provided the battalion the opportunity to rest, regroup, and prepare. Lt-Col Fred Wigle approached the task with relish. Capt Sam Chapman, the OC of D Company, disliked Wigle and was unimpressed. On the 13th of March, Chapman told his wife:

…The Col. just had a meeting in which he outlined our syllabus for the next couple of weeks – I am now convinced of what I thought of him before. He’s an extremely clever, frightfully temperamental prima-donna who understands about as much about men as I do about race horses.

The company route marches were unpopular and resulted predictably in foot problems. The war diarist, Lt Lloyd Grose took note on the 15th:

…The companies’ route marches during the morning were not as successful as the previous ones: The MO reported over 100 ‘foot-casualties’. Our companies were composed of two different groups; men who had been in action for many months, and reinforcements who had not been in the Army more than 3 – 6 months. Neither of these groups was used to long distance marches, hence the amazingly large number of casualties.

“I did what I was supposed to do because I felt a responsibility to the guys right around me”

Don Pruner was in Carl Donnelly’s platoon – 12 Platoon, B Company. At Esch, he was promoted lance-corporal and sent off on a junior NCO course. The platoon met the Regimental Sergeant Major, CWO Peter Caithness McGinlay, for the first time there:

…when a private reinforcement … joins the Battalion, he isn’t immediately aware of who the CO is … It was at this point that I actually became aware of the RSM … he came around, and he put me through this … regimental motto … it’s Albainn Gu Brath. And I remember him saying something a little bit rude, like “And remember soldier, that doesn’t mean fuck all or something” … But I remember being very impressed by him because he was quite a figure and all the NCOs held him in great awe. So I was quite struck by him … I never met the Colonel [Wigle].

…you were very familiar with the people immediately around you [referring to section and platoon levels … I wasn’t inspired by the regimental history or anything. The thing that, you know, for the short period that I was involved in action, I believe I did what I was supposed to do because I felt a responsibility to the guys right around me.

“you [are] all the girl I want”

On 21 March, Lt Grose commented that the “weather was appropriately beautiful in keeping with this, the first day of Spring.” The Commanding Officer spent time with the companies watching them “demonstrate the correct fire and movement in a company-attack.” Carl Donnelly wrote his wife on 27 March from this address “A + S H. of Canada, lst Batt.” There was not a word about where he was, what he was doing, where he had been, or what he had done:

I received your letter … and they sure make me feel a bit better when I get them … Bob must sure be some boy. And glad he is growing big. For I would not want them as small as I am (Ha ha). Well Gary is a real good boy to carrie the wood + cool in. I sure miss his footstep coming behind me. But glad that Gary & Bob Phyllis are eating better now … And don’t worry about me looking for another girl darling For you [are] all the girl I want and in the country I be in we are not allowed to speak to the civilian people.

The next day (28 March), Pte Donnelly followed the pattern first established when he went overseas. He just started his letter:

… as waiting on supper … I have sent you some money … I sent you 50 dollars to buy anything you wish. But do not buy a bond with it, so if you don’t need it put it in the bank, as we will need some [word illegible money when I get back home and I will tell you when I get home why I am sending my money home. And I have also sign you seven more dollar over from my pay … and you can do whatever you like with it. It still leaves me 25 dollar a month [.]

“I can stand most anything as long as … Gary or Bob does not have to go through what I am”

On the 29th, the “companies shifted their attention from village fighting to wood-clearing and were inspected by the C.O. at a demonstration of the latter …” The battalion left Esch the next day at 0945 hours. It was “warm and sunny … The entire population, dressed in their Sunday best for the occasion of Good Friday, was present to see us off.” The unit stopped at Kleve, Germany. Pte Donnelly sent a letter to his wife on the 30th:

… Well darling the war news sure sound[s] good. But if the hun would give up I suppose here [hear] from Russell [his brother-in-law] quite often. … I suppose Sunday is easter. I was home on leave last easter Sunday … So all you are getting for easter is your hair done I wish you would take some of the money I sent and buy yourself a good new dress and Keep yourself looking nice. But you mit [might] find someone better than me (Ha Ha0 But sure Know that you will be waiting for me when I get back. How are the children feeling and I suppose Gary will be already to start to school now. I guess you and I are starting to get old at least I feel I am. But I can stand most anything as long as I Know that Gary or Bob does not have to go through what I am. How is that Young Phyllis getting along …. I got a new pair of gloves to day from the red cross as they send a bunch of gloves + sweater[s] to the reg.t [regiment] to be given out among the lads.

The 3lst March was an auspicious day, one duly noted by the war diarist:

The Battalion crossed the Rhine, Germany’s traditional frontier, over the Blackfriar’s bridge at 1625 hrs. There were no buildings in the area assigned to us as concentration point, and the Battalion dug in for the night, protection against the elements more than against enemy activity, since there was none of the latter. …

The months of March commenced for the Argylls with some of the bitterest fighting we had yet encountered, on the approaches to the Rhine. It ended with us facing an enemy who was fighting a last-ditch defence before certain defeat; an enemy who already showed signs of evacuating large areas rather than defend himself against an Army superior in men and material.

“the original plan … changed … We were now … heading into the plains of Northern Germany”

The Argylls expected that their war would end in the Netherlands. As they awaited the next stage, the plan changed abruptly and ominously. On 3 April 1945, the unit was quartered in Lochem, “the largest and most attractive town the Argylls had liberated in Holland” in the war diarist’s estimation. In the morning a liaison officer from the 10th Brigade:

advised us … that the original plan – by which we were to go due North, swinging back into Western Holland – had been changed. We were now to go East, thence North and East again, heading into the plains of Northern Germany … At 1900 hours our convoy pulled out…

The battlefield was always dangerous, fighting on German ground was likely to be more so. The Pioneer Officer, Lt Alan Earp thought so. “I remember thinking at the time,” he wrote in November 2020:

… as we crossed at Coevorden, a grim place, that this was hardly good news for the Argylls. Liberating Dutch towns was much more fun than having to take German ones, as events would show until the bitter end. That decision had major implications for The Argylls.

The first casualties came early in April, on the 2nd. Five Argylls were wounded and another, Pte Frank T. Luposki (an original) died of wounds from artillery fire. On the 8th, the beloved Capt Malcom “Mac” Smith was killed, standing next to Lt Alan Earp, Pioneer Platoon, while discussing the crossing of the Emms River in the early morning hours. The rifle companies encountered “no opposition whatsoever” advancing through Almelo on 5 April and then through Meppen heading to Werlte on the 11th. The weather was hot, the sky was blue, and the visibility was unlimited. Often, the Argylls travelled in kangaroos, a turret-less tank with a special platform for carrying troops. The battalion reached Werlte, a little town, “at supper-time [and] we found it undamaged and free of enemy.”

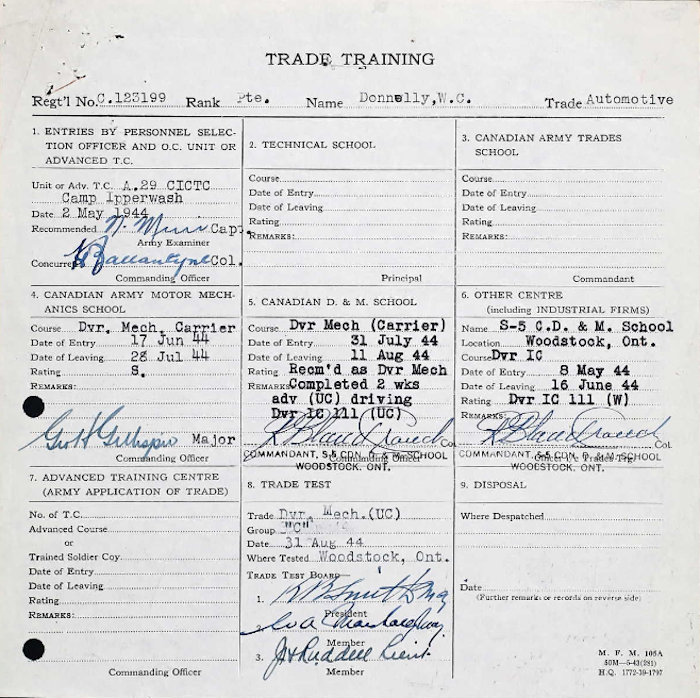

“it will soon be over I hope”

Pte Donnelly had time to write and, as always, he took advantage of it. His missive of 12 April 1945 – his last surviving letter – adhered to his traditional opening: “Well here go again with a few lines which leaves me Pretty good and sure hoping it finds your all the same at home.” He had received Hilda’s letter of 3 April and her parcel of 3 March – “… and it sure was swell.” For his part, Carl had sent home a parcel containing some souvenirs, a departure from his previous decision to bring them home with him. He asked Hilda not to send any more parcels:

… as I am on the moved [sic] most of the time. I had to give most all you[r] last one away. For I can[’]t carry them with me … So you are taking stuff for your nerves and you are run down … wish you would take better care of yourself and not worry so much about me. For it will soon be over I hope. And it will sure be swell when I can go back home to stay. And I sure have a lot to go back to …

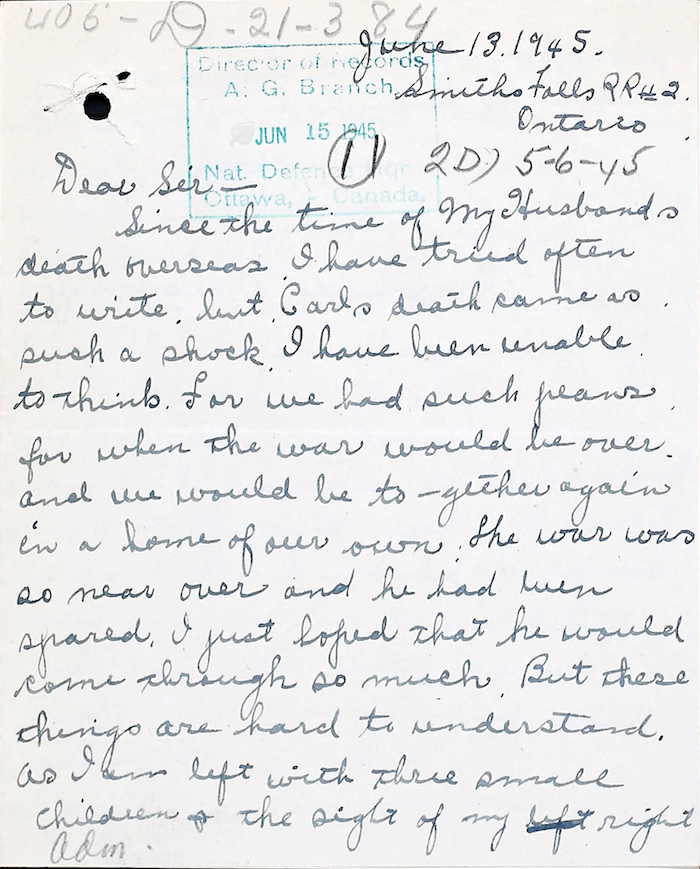

The war’s imminent end weighed heavily on Hilda Donnelly in spite of Carl’s efforts to reassure her. He revealed almost nothing of his own thoughts except for the short note in his letter of 12 February 1945 that “there is still many a hard day ahead yet.”

Carl Donnelly’s last surviving letter to Hilda and his children, 12 April 1945.

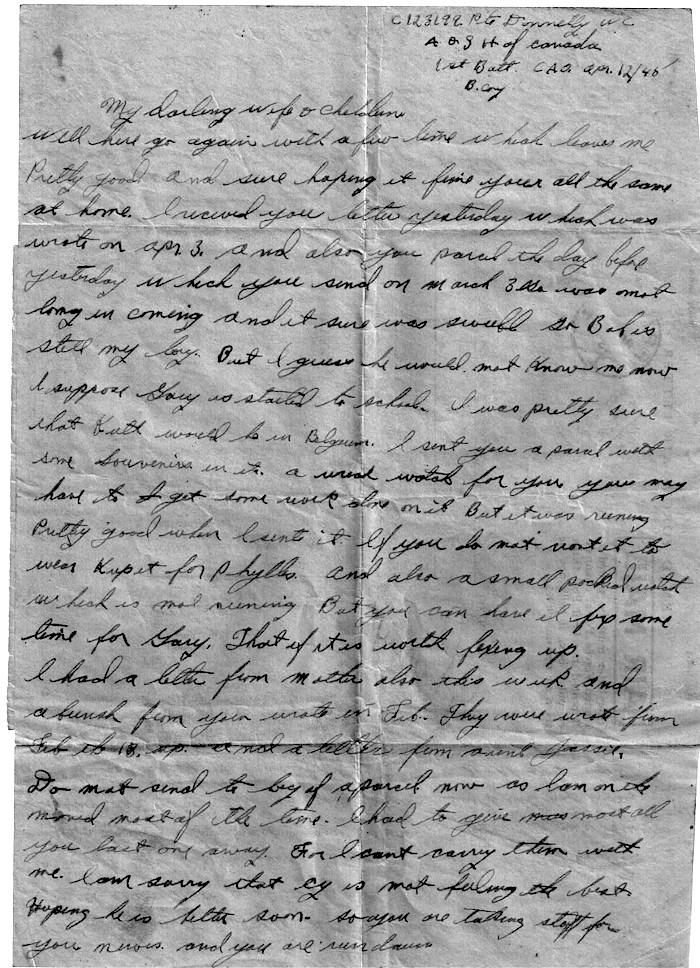

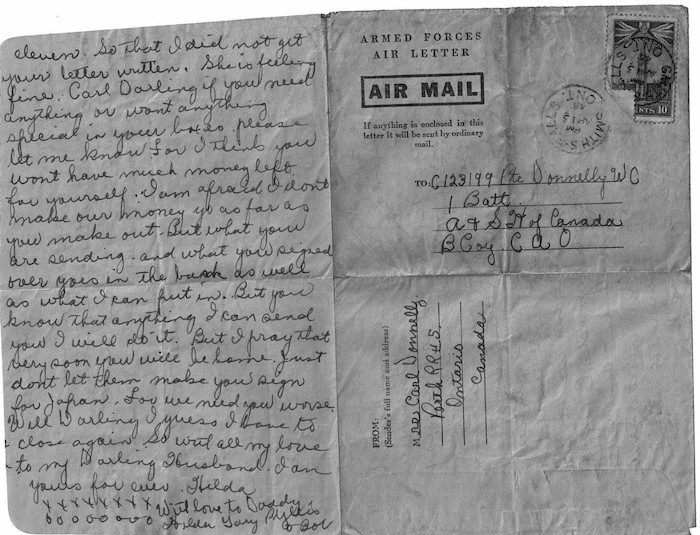

Last surviving letter from Hilda Donnelly to Carl Donnelly, 13 April 1945.

“Carl Darling”

Hilda wrote on 13 April:

Carl Darling … I received two letters from you yesterday and was I ever glad. I could hardly wait to get them opened. They were dated, March 27 + 28. But nothing in them to let me know where you are.

“But I pray that very soon you will be home … For we need you worse”

She chatted about their kids and alerted him that she would buy a bond with the money he sent or put it in the bank. She was still trying to settle the matter of what the CPR owed Carl for his “back time.” She took note of the news, especially the death of President Roosevelt and possible Canadian action against Japan:

It is also a terrible thing about Roosevelt. It sure is too bad he did not live to see the war end for he has been a wonderful man … I am afraid I don’t make our money go as far as you make out. But what you are sending and what you signed over goes in the bank as well as what I can put in … But I pray that very soon you will be home. Just don’t let them make you sign for Japan. For we need you worse … So with all my love to my Darling Husband.

“particularly the final months”

For Hilda and Carl Donnelly all that mattered was his return.

The 1st Battalion now entered its final period of sustained fighting. Capt Claude Bissell, the Adjutant, was part of the Argylls’ tactical headquarters from August 1944 until the end of the war. He carried that experience with him all his life. In 2020 Alan Earp wrote: “Claude told me once that he could not get those days out of his mind, particularly the final months, and shuddered as he said it.” The last three weeks of battle provided cogent reasons for shuddering.

Maj Hugh Maclean wrote:

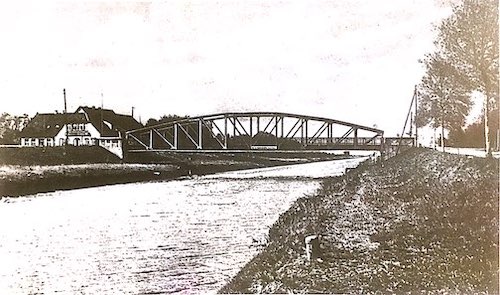

The terrain ahead was very different. Looking over the map northward from Neuvrees, one saw only a network of large and small canals, hardly any woods at all but only flat, even country, only one good north-running road and very few villages of any size. All such places, however, were invariably astride the main road. First of these was Friesoythe four miles ahead … Six miles beyond ran the east-west Kusten Kanal and on three miles more the town of Osterscheps … Dominating miles of surrounding flat and open land, the town of Friesoythe was a natural ‘bolt position and would have to be seized before further operations could be optimistically be undertaken.

“bitter cold with a strong North wind blowing”

The fighting began at Friesoythe on 14 April in the early morning hours. It was “bitter cold with a strong North wind blowing.” By 0635 hours B, C, and D companies” had advanced well into the town, leaving Tac HQ near the outskirts.” There was some fire from small arms, mortars, and snipers, but nothing sufficient “to halt their advance.” The Tactical Headquarters with Lt-Col Wigle, Lt Earp and the Pioneers, and Lt Roscoe and the Scouts came under fire from a group of retreating Germans. The commanding officer and several others, including Cpl Welby Patterson were killed; some, including Earp, were wounded; and two became POWs.

“with a fury and tenacity of purpose comparable to the spirit of the SS Panzer Divisions”

The next day B Company – now commanded by Maj Orville Zavitz – and Pte Donnelly remained in Friesoythe awaiting a bridge to be built over the Küsten Canal. Once built, B would cross and “exploit Eastward on North side of canal.” Over the next days the companies struggled to get across the canal and sustain themselves once there. On the 17th the “enemy was pasting the entire area with all he had.” The same day the Argylls got a new CO, Lt-Col Bert Coffin, from the South Alberta Regiment. The enemy forces were marines from the northeast naval ports. They fought, Maj Maclean thought, “with a fury and tenacity of purpose comparable to the spirit of the SS Panzer Divisions which had opposed the Battalion in its first actions in Normandy.” They had “every conceivable cross-road and group of buildings registered for artillery and mortar fire.” The also had an “uncertain number of self-propelled 88-millimetre guns…” B Company crossed on the 18 followed by C, which was attacked. ASgt Gerald Magee was killed of C died during the fight.

“a great deal of bitter, unpleasant fighting”

Supplying the forward companies with ammunition and food was difficult – “an exhausting, trying task” made worse by “75 and 105 millimetre gun-fire.” The road itself was “covered by the 88, which kept up a rate of fire of five or six shells a minute most of the day.” By last light B Company “was about 800 years north of the canal and had patrols 600 yards farther on.” The bridge was completed by dawn on the 19th and then destroyed by German artillery fire. Engineers repaired the bridge and the first tanks crossed it by noon. They took up positions behind houses on the far side of the canal. German guns dominated the main road and made further advance impossible. Consequently, the infantry bore “the brunt of the fighting, and did so throughout the 19th and 20th.” The forward companies, including B, were attacked, incurred casualties, but remained in place. The 4th Armoured Brigade had the Argylls under its command. The tanks “found it very difficult to manoeuvre on the soft roads which had been torn and cratered by three days of continuous shelling, both enemy and friendly.” The engineers worked on the road , the enemy shelled and knocked out the bridge again, and several “times during the night, fanatical enemy infantry counter-attacked our well dug-in forces.” About this time, Maj Maclean observed, “the limitations of an armoured division were beginning to tell on the infantry brigade, which since Friesoythe had had little rest and a great deal of bitter, unpleasant fighting.” The advance was “slow” and “desperately-contested” and “had tired the Battalion very badly.” “Heavy rain” fell the entire morning of the 20th adding to the misery of the combatants. It also reduced the likelihood of help from tanks.

“Yeah, I don’t want to be killed two weeks before the war ends or whatever”

About this juncture, there was, as LCpl Pruner of 12 Platoon, B Company, put it, “a kind of incipient mutiny.”

You wouldn’t call it a mutiny. It never developed. There was sort of a whispering campaign that when we were told to move forward the next time, we wouldn’t go. And this Company Commander [Orville Zavitz] handled it, I thought, very brilliantly. What he did was he assembled the whole company in a barn and gave a briefing about what we were going to do. And then he said, “Alright, platoon commanders, form up … platoons.” And the platoon commanders said, “Alright, sergeants, get your platoons out on the road.” And the sergeants told the corporals and the corporals told the men, and everybody was there. So that if anyone was going to start something, he had to do it in the full presence of everyone else … and so I thought that the Company Commander had handled that situation very well … a lot of that feeling was going on at that point. Yeah, I don’t want to be killed two weeks before the war ends or whatever.

“It got to the point,” Lt Harold Place, B Company, observed, “where we figured it was useless to keep going on. Just wait and eventually they would throw the sponge in. I think everybody felt the same way…”

“He took a blast of machine gun in his stomach”

B Company, like the rest of the Argyll rifle companies, was exhausted, a weariness exacerbated by the widespread realization that the war would soon be over. Yet, under Maj Zavitz’s leadership and the cadres of NCOs and other ranks, the men of B Company rallied. The continued to fight, they continued to take casualties. Pte Bob Post, B Company could not forget the 20th of April:

…the second time I was wounded I was carrying back Sergeant [Stewart F.] Wheaton [who] had got hit just north of the Küstenkanal. He took a blast of machine gun in his stomach. I forget who was our sergeant at the time, but he designated me and another fellow to get Wheaton out of there ’cause he was in bad shape. And on the way – we were carrying him out on a stretcher – we … picked up four prisoners. I don’t know where the hell they came from, we just ended up with four prisoners, so we made them carry the stretcher. And on the way back, I don’t know if it was our artillery or the Jerry’s artillery, but somebody started to lay down artillery, and I got hit again, just below the eye … And one of the Germans says to me, “You’re hurt,” and he was quite concerned ’cause I’d got hurt. It was the enemy … but he was quite concerned.

“Everybody looked after everybody else”

Pte Tom Sayer had his own moral code and, to his mind, it was the soldier’s code. As he said once, “you’d be amazed at the number of guys that looked after the other. Everybody looked after everybody else.” Certainly, Pte Sayer did his share and then some. Moreover, his everyday heroism shone at the worst of times such as when B Company was cut off in the Hochwald Gap. Lt Bill Shields thought on that occasion, as on others, Sayer should have been decorated. Pte Sayer performed similar stalwart, unflagging duty at the Küsten Canal saving the wounded yet again – and getting wounded in the process.

…I got across the bridge and was picking up wounded and bringing them back. And I went up this one road … our tanks came through and started to go up this road separating us from the Germans. They were going to just go up that road and start blasting. One got on and got blew up so I went in and took the men out of it … and got them back. Another [two] went up … and I went in and took them all out of them. And then when I got back to the medical depot, the officer says to me, “There’s some of our men laying in the roadway up there. You’ll have to go and get them.” I said, “Well, I can’t go up that road … it’s mined. The whole road is mined. The three tanks have gone up and they got blew up within five to ten feet of each other. The entire road is mined.” He says, “You gotta go and get them.” So I said, “Okay.” I went up and got blew up. That’s all there was to that. Just past the last tank that had got blown up, and my own company was laying in the marsh just off the roadway. And I waved to them, and just as I waved to them, I hit a mine…

ASgt John Glavin died on the canal during the day’s fighting.

“a particularly unpleasant night, exposed to enemy fire as well as the elements”

The 21st April brought more of the same. Bad weather always caught the eye of the unit’s war diarists and that day was no exception:

It began to rain about midnight and continued to pour steadily throughout the night. Our companies who were dug in near the rivulet, spent a particularly unpleasant night, exposed to enemy fire as well as the elements. The companies received a rum issue in the morning, as a pick-me-up after the night’s ordeal. Shortly after first light several recce patrols edged up the bank of the river, observed that all bridges were blown and that the other bank was held in some strength by the enemy. … At 1615 hours B Company assaulted across the river and successfully established a bridgehead without meeting too much opposition. They consolidated and dug in near the Southern tip of the small river [the Aue creek]…

LCpl Donald Pruner of 12 Platoon, B Company had vivid recollections of B Company’s fighting on the 21st. It combines elements of the previous days fighting and crossing of the canal as well as what happened at the “small river” where Pte Lorimer L. Johnson, 12 Platoon died.

Well, I remember they had these … .50 calibre Brownings mounted on the tank turrets as an anti-aircraft weapon. So the Argylls had got a whole bunch of these … and mounted them on Bren carriers, and they used them as a direct support weapon. They’d bring up about six of these carriers with these Brownings on them and they’d let loose and they were … a ferocious weapon. I remember they were firing them directly over our heads as we crossed the [Küsten] canal.

The other thing I remember … the canal was very small. I mean I recall something in width being less than … [thirty feet], so that by the time we all threw all these assault boats into it, you could almost throw all the assault boats in and just walk across them, you know. I don’t recall having to get in the boat and sort of paddle it across. We just threw all the boats in and more or less scrambled across them…We were crossing exactly where there was a road, which was a bad place to cross as it was obvious that the Germans had artillery and mortars zeroed in on it. So we crossed and again, I don’t know quite why, but we were digging in on the far bank of the canal, which was kind of a dumb place … because that’s also where the Germans would have it marked.

So we started to get a lot of incoming mortar fire, and I remember there was a negro named Johnson who was about two slit trenches down from me, and he was hit. And he started to slip into the water, so I ran down with another guy and we dragged him – by the time we got to him, he was … down to about his waist in the water, and we dragged him out and … stuffed him into the hole he’d been digging, and then came back and went on digging our own holes. And he died, and he probably was dead when we pulled him out of the water … would probably have been in his thirties when he was killed.

“when that lad was killed, the fellows were so upset”

Johnson’s death upset 12 Platoon. LCpl Earl Stillman explained what happened:

…We had a black kid from down on the east coast with us. And that poor fellow, when [he] got into action, his eyes would just bug out … But when that lad was killed, the fellows were so upset that they turned around and went right back to that town … and they just destroyed it. They just seemed to [want] revenge…

“under fire almost continuously”

On 22 April, “the rain, which had last[ed] almost two days, finally stopped this morning, but the weather continued to be fairly cool.” During the night, the engineers constructed a bridge over the river sufficient to get Argyll company vehicles across. B and C companies moved north towards Osterscheps capturing their two objectives “against moderate opposition.” The war diarist took stock of the state of the rifle companies:

After the last three days’ fighting, during which the companies had been under fire almost continuously, their fighting strength had been reduced to about 55 – 60 each in A, B and C, with only 47 remaining in D. With our fighting strength thus cut down about 50%, it was imperative that we be assigned some reinforcements before setting out on a new major task.

The next day the war diarist reported that “since crossing the Küsten canal the Argylls had suffered 150 casualties. The unit was “most happy to hear that 90 reinforcements were about to proceed to F-Echelon and the companies.” B Company had only 2 officers and 53 other ranks. The 23rd had casualties as well and Pte Colin “Buddy” MacLennan was one of them.

Whether Pte Donnelly managed to write Hilda after 12 April is not known. If he could manage it, he wrote, but the fighting had been continuous since the 14th. Doubtless, had there been the slightest opportunity, he would have managed. Although his immediate world was far removed from Port Elmsley, the Rideau lakes, his home with Hilda and the kids, it is inconceivable that they were far from his thoughts. He had warned Hilda in February that there were difficult days still ahead. On 24 April, Carl Donnelly lived his last day.

“Progress was slow, due to MG and sniping fire as well as some sporadic mortaring”

The war diarist provides a sense of how that fateful day unfolded for Carl Donnelly and the three others killed:

At 0500 hours, under cover of the very thick morning mist engulfing the area, the enemy counter-attacked B Company by infiltration. By 0600 hours the situation had been completely restored, but the enemy began to shell the entire area very consistently and heavily. For the first time in this operation he was using 21 cm shells — highly effective from a physical as well as psychological point of view!! The counter-attack had upset our timetable for the morning’s attack and H-Hour was postponed.

Morning weather: clear and warm. B Company started on its task at 1015 hours, supported by a troup [sic] of tanks. Progress was slow, due to MG and sniping fire as well as some sporadic mortaring. They reached general area … at 1130 hours, taking several PW on the way. They were pinned down at this point by MG fire until almost 1400 hours. At 1420 hours they reached … against continued opposition, now including bazookas. 7 casualties had been sustained up to this time.

The CO had moved to the town of Osterscheps during the morning and advised B Company at 1515 hours to withdraw to … a firm base, leaving only an OP at their forward position … We were advised in the afternoon that we were once more reverting to under command 4 Cdn Armd Bde, and that our job for the present would be to hold a semi-circular arc around the town of Osterscheps, controlling the roads North West, North, and North East of the town.

The balance of Tac HQ moved into the town … A Company, pushing East along the main road out of town, ran into very heavy opposition near the road block … D Company, under continuous mortar and sniping fire, advanced as far as … shortly after supper. The balance of the Battalion took up positions in the little town itself. By 2100 hours the forward companies reported the general situation as much quieter, as the enemy had evidently shifted his attention towards the town. A substantial number of shells and mortars were screaming into town, but outside of a few small shrapnel holes in some of the vehicles, no damage or casualties were sustained.

Articles in the British press led us to believe that the war was as good as over and that fighting had practically ceased. However, various Argyll personnel hunched over assorted benches and desks during the shelling gave ample evidence of the premature optimism manifested by the respective authors of these articles.

Four Argylls, including Carl Donnelly died on the 24th, five were wounded. These statistics underlie the Argyll cynicism to newspaper declarations that “fighting had practically ceased.”

LCpl Don Pruner had served with Pte Carl Donnelly since they joined the Argylls on the 1st and 2nd of March. Pruner was with Carl Donnelly when he was wounded as was Pruner. He detailed what happened:

…we were advancing, we were again working with an armoured unit, like advancing up this road … sort of raised roads. So we were going ahead of the tanks, sweeping, making sure there were no Germans with Panzerfausts … and they were shooting over our heads.

And it was very flat country there … the tanks were … hitting the house and barns that they could see and sweeping the hedgerows with the machine gun fire. And we were coming under quite a bit of fire.

I recall one fact. At one time when we come … off to the side of the road … you know the snapping noise a bullet makes when it goes over your head? Heard a couple of those and … looked around behind me to see bullet holes in the door … the wall of the barn. And we were, you know, guys were being hit and so forth, so it was … late in the afternoon.

There were farm houses and I remember some German family, like coming down the road with their hands up with a white flag, just some civilians, like a man, two women holding up an old man who had been shot in the leg or something, they were helping him along…

…towards the end of the day … late afternoon let’s say, and somebody had decided that was enough for today, we weren’t going to advance any further. So I think company headquarters was back at the next crossroads, and so we were, I guess they fed the rear platoons and they were bringing the guys forward and we were just to go back to have supper, like, and replace, you know, leapfrog a platoon.

“Donnelly and I who were going back together, and we were under fire at that point”

So there was a fellow named Donnelly and I who were going back together, and we were under fire at that point … sort of sniper type fire. And Donnelly and I, we crawled a bit and ran a bit, and then rather stupidly, we said, “Well, I guess we’re back far enough now,” and we just started walking along the side of the road.

“it must have been a burst of machine gun fire, but they hit both of us”

Now, under those circumstances, you’re very tired. You don’t rest properly and even when you’re resting, you’re not comfortable, so you get kind of dopey and tired and you’re not thinking straight … And it must have been a burst of machine gun fire, but they hit both of us like, and I think his name was Donnelly, and he was killed.

“he didn’t die right away, ’cause I could hear him. He was calling for help”

…I don’t think he died right away. In fact I know he didn’t die right away, ’cause I could hear him. He was calling for help, so he was conscious. But I heard that he had died later on. And in my case, I was just wounded, just hit me in the back and skidded around my rib cage and went through my left biceps … the feeling was like a hot poker being jabbed into my side and a sledge hammer hitting my arm, and then the whole arm just went numb. So it was not a lot of pain, at that time.

…And I remember opening my battle dress jacket and looking down and seeing some blood right on the front of this sweater [knitted by his mother’s neighbour] … but I remember thinking, Jesus, I must be worse hit than I feel. But I knew that I wasn’t, you know, I knew I’d been hit of course, but I didn’t feel that I was mortally wounded or anything like that.

“we called … yelled stretcher bearer and that kind of thing”

…Well, we called … yelled stretcher bearer and that kind of thing, and a couple of guys came out with a stretcher and had the arm band on. The Germans kept firing at them, and I told them I was able to walk, which I was; but they had to crawl along, crouching in the ditch, because the Germans were still firing at us. And I just got myself back … I think they put a bandage, a field dressing on my arm … But they took me back to company headquarters … and then … from there they had one of those jeep ambulances with the stretchers … took me back to RAP.

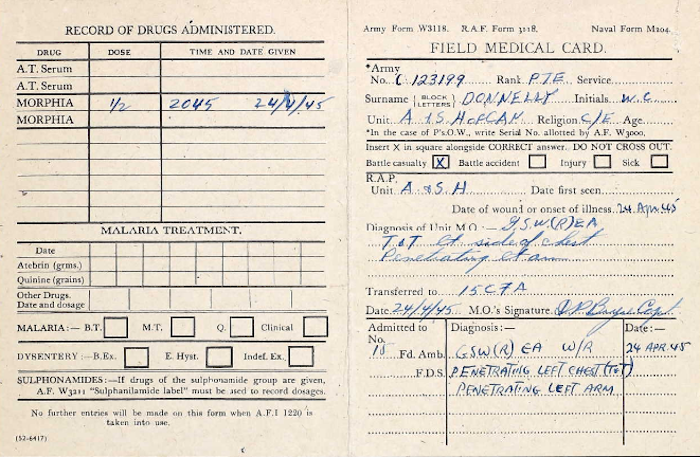

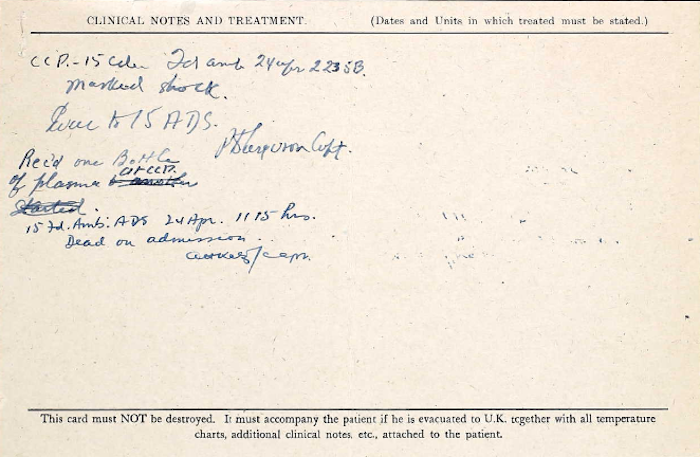

“dead on admission”

Capt Doug Bryce, the unit’s Medical Officer, examined Pte Donnelly at the Regimental Aid Post and diagnosed a “G.S.W. (R) EA T & T lt side of chest Penetrating lt arm.” Donnelly received a half dose of morphine at 2045 hours. He was transferred to 15 Canadian Field Ambulance Casualty Clearing Post at 2235 with “Marked shock” and evacuated to 15 Army Dressing Station; he was “dead on admission.”

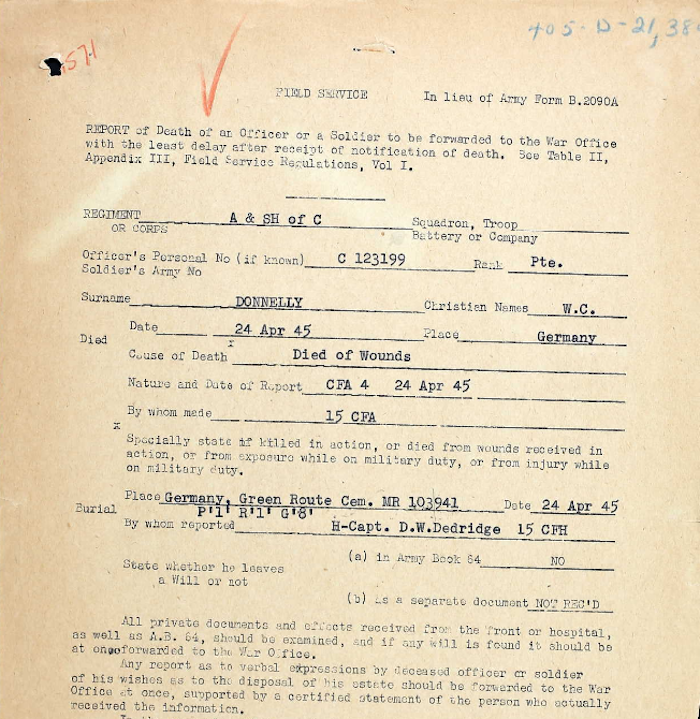

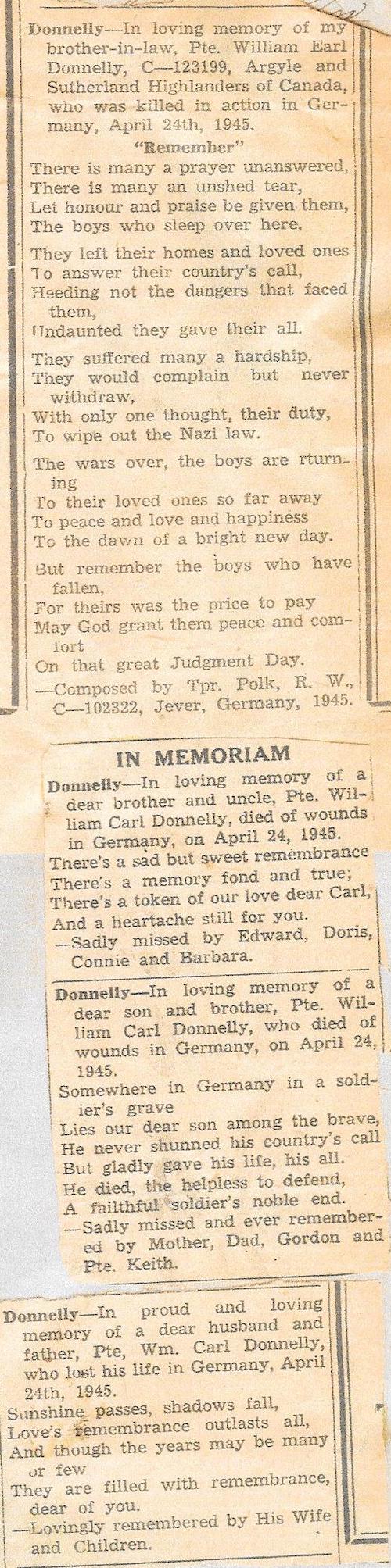

HCapt E.W. Eldridge, the padre of 15 Canadian Field Ambulance, buried Pte Donnelly on the 24th in Germany at the “Green Route Cem.” He wrote to Hilda Donnelly on 4 May 1945:

… as the chaplain who buried him it is my priviledge [sic] to write expressing our sympathy and in a measure at least to share your sorrow with you. Of the circumstances of his being wounded I can tell you nothing. When wounded he was evacuated through one of our CCPs to our ADS but died enroute because of the seriousness of his wounds. May I assure you that everything possible is done to save a life but casualties are sometimes so badly wounded that the doctors can do little more than bandage their wounds, make them as comfortable as possible, and hope for the best.

“you were greatly attached and meant much to each other”

I know from mail which your husband was carrying at the time of his death that you were greatly attached and meant much to each other and were looking forward to the time of your reunion after the war. Because of this I know you are mourning the loss of your loved one and are no doubt finding it difficult to make plans for your own future and that of your family. I would [wish] that I might write words of great comfort and in some way lighten the burden of our sorrow. That I cannot do, but there is one who has promised comfort to every aching heart. He has promised that he will strengthen every struggling Spirit and comfort all those who mourn and to Him I commend you. May you find in Him a source of consolation and strength sufficient unto your need.

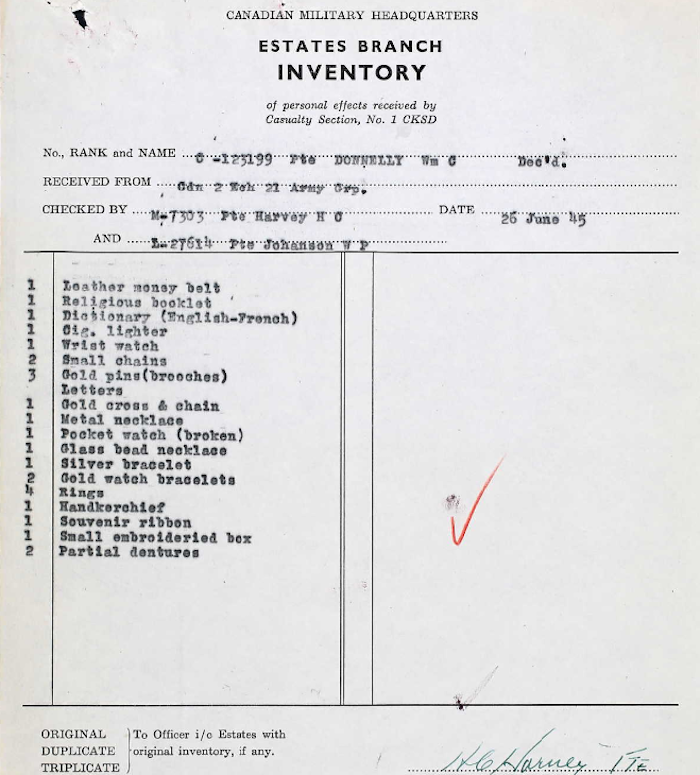

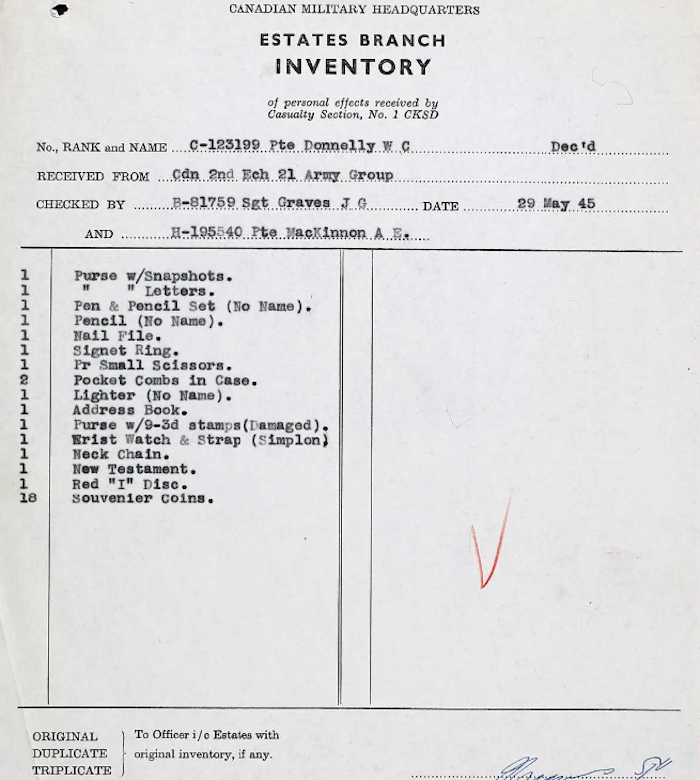

“three “Gold pins (brooches)”

Pte Donnelly had more personal effects overseas than most soldiers: a leather money belt, a religious booklet, a French-English dictionary, a cigarette light, a watch, two “small chains,” three “Gold pins (brooches),” letters, a gold cross and chain, a metal necklace, a pocket watch, a glass bead necklace, two gold watch bracelets, four rings, a handkerchief, souvenir ribbon, a small embroidered box, a purse with “Snapshots,” a purse with letters, a pen and pencil set, a pencil, a nail file, a signet ring, a small pair of scissors, pocket combs “in case,” a lighter, an address book, a purse with “9-3d stamps,” a wrist watch and strap, a neck chain, a New Testament, 18 souvenir coins, and a red identity disc. Obviously, many of these items were gifts for his wife and children, which he hoped to bring home to them.

“your late husband died as a result of bullet wounds to the left chest and left arm”

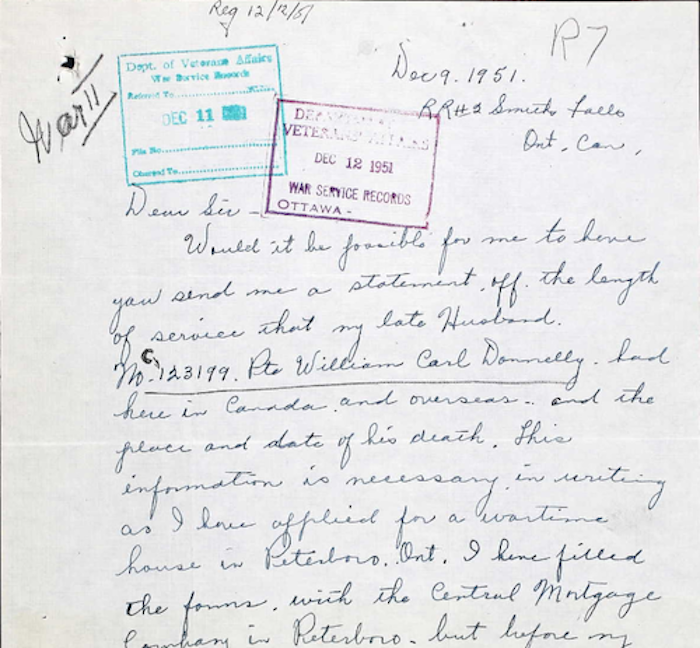

The Director of Records wrote to Hilda Donnelly on 10 May, further to the telegram of 28 April that “your late husband died as a result of bullet wounds to the left chest and left arm.” She had worried about her husband’s safe return from the time he joined the army. She wrote letters, sent parcels, and saved every penny for his return home and their future live. For his part, he tried to be reassuring. His letters, written almost daily, had a pattern calculated to assuage her unease. He rarely mentioned the war or what he was doing and, as he moved closer to the battlefield, he focused increasingly on her comfort and her health. He desperately wanted to buy her something but she ignored his pleas and the money went to a bond or the bank.

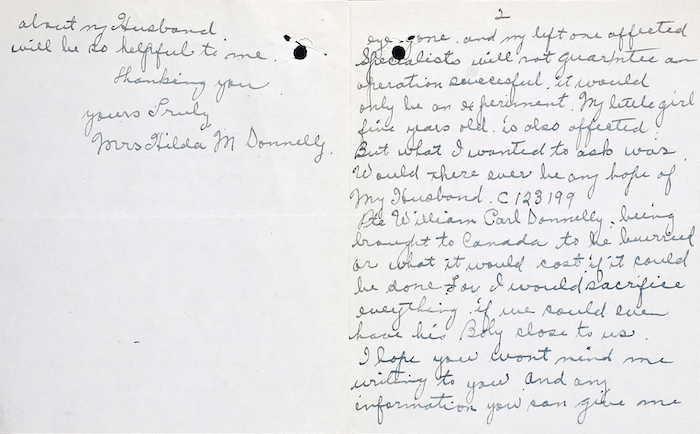

“I would sacrifice Everything if we could even have his Body close to us”